Abstract

Although Treg-cell-mediated suppression during infection or autoimmunity has been described, functions of Treg cells during highly pathogenic avian influenza virus infection remain poorly characterized. Here we found that in Foxp3-GFP transgenic mice, CD8+ Foxp3+ Treg cells, but not CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg cells, were remarkably induced during H5N1 infection. In addition to expressing CD25, the CD8+ Foxp3+ Treg cells showed a high level of GITR and produced IL-10. In an adoptive transfer model, CD8+ Treg cells suppressed CD8+ T-cell responses and promoted H5N1 virus infection, resulting in enhanced mortality and increased virus load in the lung. Furthermore, in vitro neutralization of IL-10 and studies with IL-10R-deficient mice in vitro and in vivo demonstrated an important role for IL-10 production in the capacity of CD8+ Treg cells to inhibit CD8+ T-cell responses. Our findings identify a previously unrecognized role of CD8+ Treg cells in the negative regulation of CD8+ T-cell responses and suggest that modulation of CD8+ Treg cells may be a therapeutic strategy to control H5N1 viral infection.

Keywords: CD8+ Treg cells, H5N1 influenza virus, IL-10

Introduction

Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus poses a pandemic threat with continuously occurring widespread infections of avian species and humans [1,2]. A potent host immunity can be primed to protect against acute H5N1 viral infection [3,4]. Although the immune responses present a powerful barrier and might be required to clear highly pathogenic influenza viruses, they are also implicated in immune-mediated lung injury [5,6]. Patients infected by H5N1 virus frequently had the syndromes of acute respiratory distress syndrome, multiple organ dysfunction, lymphopenia, and hemophagocytosis, resulting in a mortality rate of approximately 60% [7–9]. These syndromes have previously been associated with abnormally strong innate and adaptive immune responses [10–13].

Treg cells are important mediators of immune homeostasis with naturally endowed immune-suppressive activity [14–17]. To date, multiple Treg-cell subsets (e.g. nTreg cells, Tr1 cells, Th3 cells, CD8+ Treg cells, etc.) can exert negative immunoregulatory effects on the activation and effector functions of innate and adaptive immune cells by diverse mechanisms [14]. In addition to suppressing autoreactive cells, Treg cells play a central role in protecting host tissues from immune-mediated damage during viral infection [18,19]. For example, in infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) induction of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells was shown to be associated with a reduction of immune pathology and better clinical outcome [20]. A recent study showed that CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells could delay IAV-induced mortality and a combination of virus neutralizing antibodies and transferred Treg cells led to the complete prevention of clinical disease following H1N1 viral infection [21]. Another study demonstrated that antiviral CD8+ and CD4+ effector T cells controlled lung inflammation during acute influenza H1N1 viral infection by producing IL-10 [22]. These findings indicated that there can be suppression of immune pathology by Treg cells during viral infection. However, pertaining to primary infection with H5N1 virus, we do not yet know whether Treg cells are induced to control immune-mediated damage or which Treg-cell subsets are involved in prevention of clinical disease.

In this study, using Foxp3-GFPtg mice infected by H5N1 virus, we have demonstrated that H5N1 virus infection could induce a subset of CD8+ T cells that have a phenotype of CD25+Foxp3+IL-10+, and inhibit CD8+ T-cell responses by some IL-10-dependent mechanism. Our findings thus provide novel insights into the virus/immune system interactions during H5N1 virus infection.

Results

CD8+ Treg cells are increased during avian H5N1 influenza virus (AIV) infection

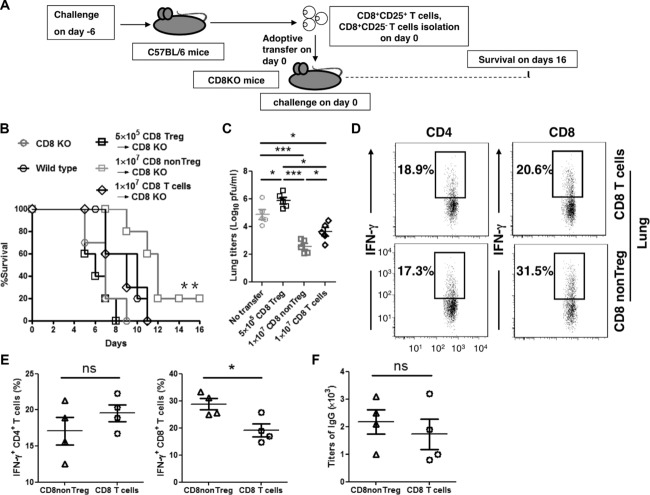

Foxp3 is necessary for Treg-cell generation and function and remains the most definitive marker of Treg cells [23–25]. We first determined whether Treg cells were induced by seeking Foxp3 expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells taken from Foxp3-GFPtg mice during H5N1 virus infection. Through days 0, 3, and 6 after H5N1 virus infection, the frequency of CD4+ Treg cells remained unchanged in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), in splenic cells, and in lungs (Supporting Information Fig. 1A and B). Also, the number of CD4+ Treg cells in the bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) was not changed (Supporting Information Fig. 1C). In contrast, we observed that the frequency of CD8+ Treg cells was remarkably increased in PBMCs, spleen, and lung (Fig. 1A and B). In addition, the numbers of CD8+ Treg cells in the BAL and spleen were significantly increased (Fig. 1C). Similar results were observed in AIV-infected C57BL/6 mice (Supporting Information Fig. 2), indicating that CD8+ Treg cells were also induced in the parent nontransgenic mouse during H5N1 virus infection.

Figure 1.

Induction of CD8+ Treg cells in Foxp3-GFPtg mice during H5N1 viral infection. (A) Surface staining of CD8 on the PBMCs, lung cells, and spleen cells taken from Foxp3-GFPtg mice on days 0, 3, and 6 after infection with H5N1 virus. The dot plots represent one of three independent experiments with similar results (n = 5 mice). (B) Statistical analysis of Foxp3+ cells in total CD8+ T cells (%). (C) Surface staining of CD8 on the spleen and BAL cells taken on days 0, 3, and 6 from Foxp3-GFPtg mice infected with H5N1 virus. The number of CD8+Foxp3+ T cells is shown (n = 5 mice). (B and C) Data are from one experiment representative of three separate experiments. *p < 0.05, unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Analysis of phenotype and cytokine profile of CD8+ Treg cells

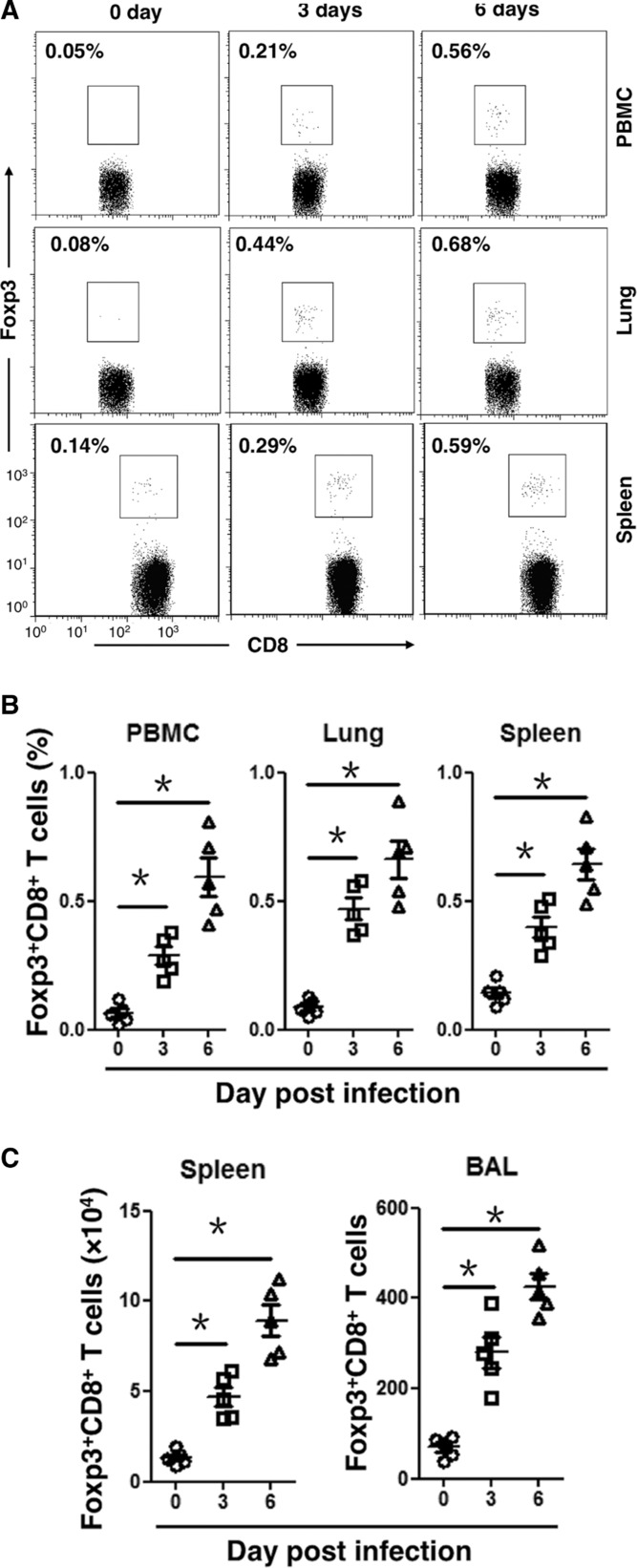

To characterize Treg-cell phenotype, we looked for signature molecules, including CD25, GITR, CTLA-4, and PD-1, which are known to associate with the CD4+ Treg cells. We observed that most CD8+Foxp3+ Treg cells expressed CD25 and GITR with low levels of CTLA4 and PD-1 (Fig. 2A). Since nearly all CD8+Foxp3+ Treg cells expressed CD25, we isolated CD8+CD25+ T cells from spleens of AIV-infected Foxp3-GFPtg mice on day 6 to do further analysis. The purity was approximately 85% (Supporting Information Fig. 3). The high level of Foxp3 gene expression was confirmed in AIV-induced CD8+CD25+ T cells by qRT-PCR (Fig. 2B), indicating that these cells were CD8+ Treg cells. Interestingly, IL-10 mRNA was highly expressed in AIV-induced CD8+CD25+ Treg cells, whereas the mRNA levels of TGF-β, IFN-γ, perforin, granzyme B, and FasL in the CD8+CD25+ Treg cells were not obviously different from those of naive CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Phenotpyes of primed CD8+Foxp3+ T cells. (A) Surface staining of CD8, CD25, GITR, CTLA4, and PD-1 on the splenic cells taken from Foxp3-GFPtg mice on day 6 after infection with H5N1 virus. The dot plots represent one of four independent experiments with similar results (n = 5 mice). (B) Splenic CD8+CD25+ T cells from Foxp3-GFPtg mice on day 6 after H5N1 viral infection were purified for quantitative RT-PCR. Naïve CD8+ T cells were purified from naïve Foxp3-GFPtg mice as control. Data are shown as mean + SEM and are pooled from three independent experiments. **p < 0.01. n.s., p > 0.05, unpaired two-tailed t-test. (C) Splenic cells were isolated on day 6 from Foxp3-GFPtg mice infected by H5N1 virus and were stimulated with 5 μg/mL NP peptide (NP366–374) or no peptide. Cells were incubated for 6 h with 2 μM monensin before intracellular staining. CD8+ T cells were gated to analyze the expression of Foxp3 and IL-10. The dot plots represent one of three independent experiments with similar results (n = 5 mice).

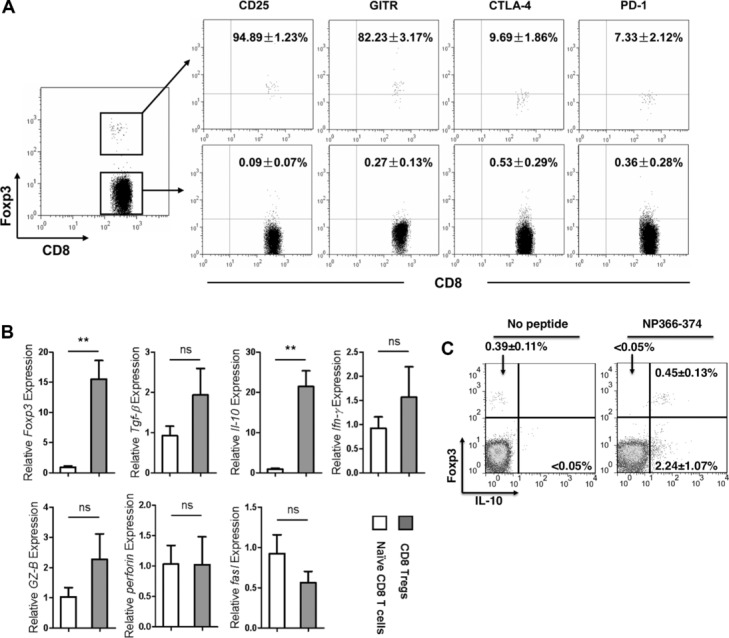

To further assess AIV-induced CD8+CD25+ Treg cells secreted IL-10, we performed intracellular analysis on splenocytes taken on day 6 from AIV-infected Foxp3-GFPtg mice. The cells were stimulated in vitro with 10 μg/mL of NP366–374, an NP antigen-specific peptide of AIV. The level of IL-10 expression was high in the CD8+Foxp3+ T cells (Fig. 2C). In addition, the high level of IL-10 expression was confirmed by the use of IL-10-GFPtg mice infected with H5N1 virus. We observed that about 90% of AIV-induced CD8+CD25+ T cells were IL-10 positive (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Primed CD8+CD25+ T cells expressed IL-10. Splenic cells were isolated on day 6 from IL-10-GFPtg mice infected with H5N1 virus and surface stained for CD8 and CD25. CD8+ T cells were separated into CD25 positive and negative cells. These cells were further divided into GFP positive or negative, with GFP serving as a marker for IL-10 positivity. The percentages of CD8+CD25+ T cells and CD8+CD25− T cells that were IL-10+ or IL-10− are shown together with results of statistical analysis. The dot plots represent one of five independent experiments with similar results (n = 5 mice).

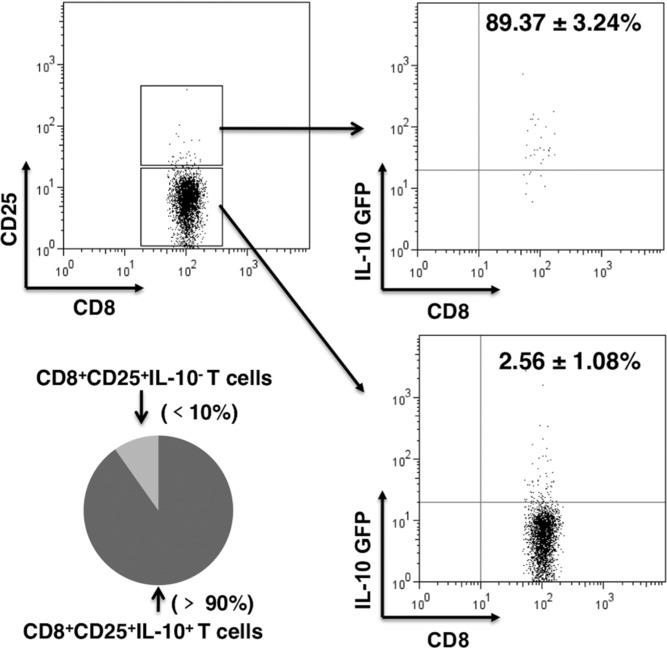

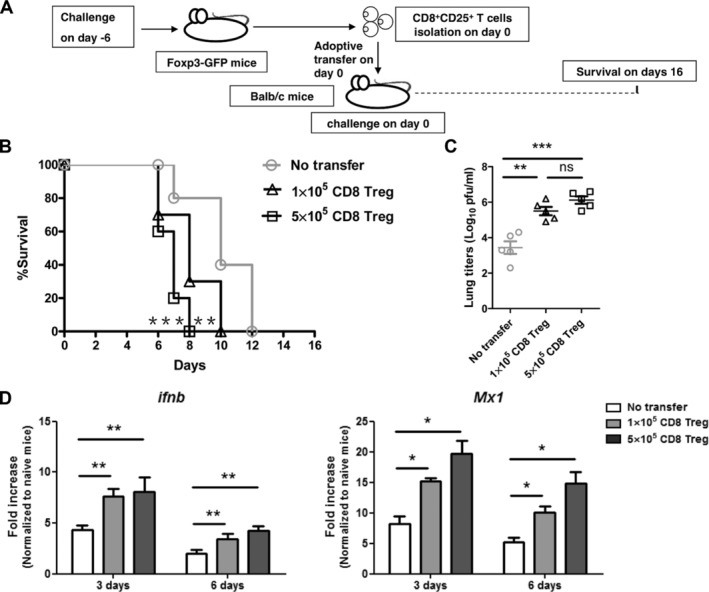

CD8+ Treg cells facilitate AIV-induced mortality

To study the effect of CD8+ Treg cells on the immune response against AIV, we adoptively transferred various numbers of purified CD8+CD25+ T cells from H5N1-infected donor mice into naive syngeneic recipients. The recipients were challenged with a lethal dose of H5N1 virus immediately upon receipt of the transfer (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the transferred CD8+ Treg cells promoted disease progression and shortened survival time of the recipient animals compared to the controls (Fig. 4B). A higher level of mRNA of H5N1 HA, an indicator of viral replication, was observed in the lungs of CD8+ Treg cells recipients compared to those that did not receive the CD8+ Treg cells (Fig. 4C). Higher transcript levels of IFN-β and Mx-1 have been reported to be associated with viral replication [26] and we found higher levels of IFN-β and Mx-1 in the lungs of mice that had received CD8+ Treg-cell transfer than in the lungs of those that had not (Fig. 4D). These observations indicated that CD8+ Treg cells promoted H5N1 viral replication. To exclude potential effects of endogenous CD8+ T cells of the recipient mice on the suppressive function of the transferred CD8+ Treg cells, we repeated the adoptive transfer experiments but using naive CD8-deficient (CD8 KO) mice as the recipients (Fig. 5A). Compared to wild-type mice, the CD8 KO mice developed accelerated clinical manifestations and succumbed more rapidly to infection, suggesting an antiviral activity of CD8+ T cells. Nevertheless, mortality was further accelerated when AIV-infected CD8 KO mice received CD8+ Treg cells. In contrast, the transfer of CD8+ T cells or CD8+CD25− T cells extended their survival (Fig. 5B). Importantly, higher AIV loads were observed in lungs of the AIV-infected CD8 KO mice that had received the CD8+ Treg cells than other recipient groups. The virus load was lowest in the lungs of AIV-infected CD8 KO mice that had received CD8+CD25− T cells (Fig. 5C). To further dissect the effects of CD8+ Treg cells on influenza-specific immune responses, we tested CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the lung for IFN-γ expression and tested serum for influenza-specific IgG level. The percentage of lung CD4+ T cells that produced IFN-γ was about the same in mice that received either total CD8+ or only CD8+CD25− T cells. However, the percentage of lung CD8+ T cells that produced IFN-γ was substantially increased in mice that received only CD8+CD25− T cells compared to mice that had received total CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5D and E). The influenza-specific serum IgG titers were about the same in mice that received either CD8+CD25− T cells or total CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5F). Thus the data indicated that AIV-induced CD8+ Treg cells were suppressing the CD8+ T cell-responses in vivo.

Figure 4.

CD8+ Treg cells resulted in enhanced mortality and increased virus load in the lung. (A) Splenic CD8+CD25+ T cells were isolated on day 6 from Foxp3-GFPtg mice infected with H5N1 virus. The cells were transferred into BALB/c mice (1 × 105 or 5 × 105 CD8+CD25+ T cells per mouse) and the mice (n = 10 mice per group) were then immediately challenged with H5N1 virus. (B) Survival of mice was monitored from day 7 to 16 after virus infection. Log-rank test for comparisons of survival curves between control mice and CD8+ Treg cells recipient mice; **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001, log-rank test. (C) Lung viral load was assayed on day 6 after virus infection (n = 5 mice per group). (D) Total RNA was extracted from lung for real-time PCR for IFN-β and Mx-1. Data are shown as mean + SEM and are pooled from three independent experiments. n.s., p > 0.05. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001, unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Figure 5.

CD8+ T-cell immunity was inhibited by CD8 Treg cells in vivo. (A) CD8+CD25+ T cells, CD8+CD25− T cells, total CD8+ T cells were isolated from spleens of C57BL/6 mice on day 6 after infection with H5N1 virus and were transferred to CD8 KO mice. 5 × 105 CD8+CD25+ T cells, 1 × 107 CD8+ CD25− T cells, or 1 × 107 CD8+ T cells were transferred into each mouse (n = 10 mice per group). (B) Mouse survival was monitored from day 4 to 16 after virus infection. Log-rank test for comparisons of survival curves between CD8+ T-cell recipient mice and CD8+CD25− T-cell recipient mice; **p < 0.01 (n = 10 mice per group), log-rank test. (C) Lung viral loads were assayed on day 6 after virus infection (n = 5 mice per group). (D). Lung cells taken on day 8 of infection were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 5 h in the presence of monensin and then stained to detect intracellular IFN-γ expression in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (n = 4 mice per group). (E) Statistical analysis of IFN-γ+ cells among CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (%). (F) Serum total H5N1 virus-specific IgG titers, assayed by ELISA on day 8 post virus infection (n = 4 mice per group). Mice receiving CD8+CD25− T cells served as CD8nonTreg-cell controls. Data are presented as means ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001, unpaired two-tailed t-test.

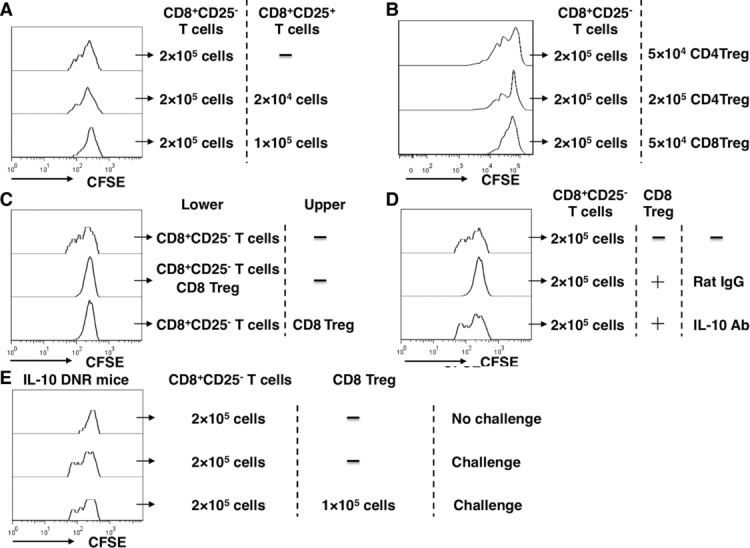

IL-10 is involved in the inhibition of CD8+ T-cell proliferation by CD8+ Treg cells

Since suppressive function is a hallmark of Treg cells, we next tested for suppressive function of AIV-induced CD8+ Treg cells in vitro. Splenic CD8+CD25+ T cells, CD8+CD25− T cells, and CD11c+ cells were purified on day 6 after the AIV viral infection of C57BL/6 mice. We stimulated CD8+CD25− T cells with CD11c+ cells and 10 μg/mL NP366–374 peptide in the presence of various numbers of CD8+ Treg cells and measured the proliferation of the target CD8+CD25− T cells on the basis of CFSE dilution. As shown in Fig. 6A, the proliferation of CD8+CD25− T cells was suppressed by the addition of CD8+ Treg cells in a dose-dependent manner. We compared CD8+ Treg cells with CD4+ Treg cells for suppressive function against the proliferation of CD8+CD25− T cells. CD8+ Treg cells were much stronger suppressors (Fig. 6B). We also tested whether this suppressive effect was dependent on cell–cell contact by the use of a transwell co-culture system. Again, co-culture with CD8+ Treg cells significantly inhibited CD8+CD25− T-cell proliferation (Fig. 6C), indicating that the suppression was a contact-independent event and that soluble factor(s) might play a role in the suppression. To test this notion, we added anti-IL-10 neutralizing antibodies into the co-culture assay and used isotype-matched antibodies as controls. We observed that the suppressive effect of CD8+ Treg cells was abolished by the addition of anti-IL-10 antibodies (Fig. 6D), indicating a critical role of IL-10 as the mediator of the CD8+ Treg-cell effect. To confirm the role of IL-10 in vitro, DNIL-10R mice (dominant-negative IL-10R-α Tg mice, [27,28]) were employed to provide CD8+ T effectors since CD8+ T cells of DNIL-10R mice constitutively express IL-10R-α and consequently deplete IL-10 (Supporting Information Fig. 4). Splenic CD8+CD25+ Treg cells and CD11c+ cells were purified from wild-type (WT) mice and CD8+CD25− T cells were purified from DNIL-10R mice on day 6 after viral infection. In the absence of IL-10 signaling, CD8+ Treg cells failed to suppress CD8+ T cells proliferation (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6.

CD8+CD25− T-cell proliferation was inhibited by CD8+ Treg cells through IL-10 in vitro. (A) CD8+CD25+ T cells, CD8+CD25− T cells, CD11c+ cells were isolated on day 6 from spleens of H5N1-infected C57BL/6 mice. CFSE-stained CD8+CD25− T cells were stimulated to proliferate in vitro; 2 × 105 CD8+ CD25− T cells and 5 × 104 CD11c+ cells were stimulated with 10 μg/mL NP366–374 peptide in the presence of different numbers of CD8+ Treg cells for 5 days. (B) CD4+CD25+ T cells, CD8+CD25+ T cells, CD8+CD25− T cells, and CD11c+ cells were isolated from spleens of C57BL/6 mice on day 6 after infection with H5N1 virus. CFSE-stained CD8+CD25− T cells were stimulated to proliferate in vitro; 2 × 105 CD8+ CD25− T cells and 5 × 104 CD11c+ cells were stimulated with 10 μg/mL NP366–374 peptide in the presence of different numbers of CD4+ or CD8+ Treg cells for 5 days. (C) 2 × 105 CD8+ CD25− T cells and 5 × 104 CD11c+ cells were stimulated with 10 μg/mL NP366–374 peptide in the presence of 1 × 105 CD8+ Treg cells in transwell plates for 5 days. (D) T-cell proliferation was done with 50 μg/mL anti-IL-10 mAb or isotype control antibodies in the wells. The number of CD8+ Treg cells used in the system (C and D) was 1 × 105. (E) CD8+CD25+ T cells and CD11c+ cells from C57BL/6 mice and CD8+CD25− T cells from DNIL-10R mice were isolated 6 days after infection with H5N1 virus and T-cell proliferation assays were performed. (A–E) Data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments with four mice per group.

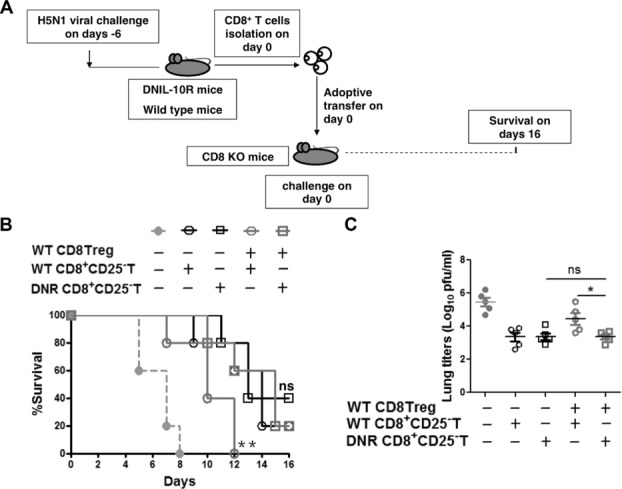

CD8+ Treg cells inhibit CD8+ T-cell responses in vivo by IL-10

To confirm the role of IL-10 in vivo, we compared the effects of adoptively transferring CD8+CD25− T cells and CD8+ Treg cells from WT or DNIL-10R mice. The donor mice had been infected with H5N1 virus and the recipients were CD8 KO mice that were then immediately challenged with H5N1 (Fig. 7A). When WT CD8+ Treg cells were transferred together with DNIL-10R CD8+CD25− T cells, survival was not significantly reduced (Fig. 7B) and viral load was not higher (Fig. 7C) compared to mice that received only DNIL-10R CD8+CD25− T cells. However, transfer of DNIL-10R CD8+CD25− T cells with WT CD8+CD25+ T cells significantly increased survival (Fig. 7B) and reduced viral load (Fig. 7C) compared to mice that received WT CD8+ Treg cells and WT CD8+CD25− T cells. This data demonstrated that IL-10 signaling by CD8+CD25− T cells was necessary for CD8+ Treg cells to inhibit the CD8+ T-cell responses in vivo.

Figure 7.

The antiviral activity of CD8+CD25− T cells was inhibited by CD8+ Treg cells in vivo through IL-10. (A) CD8+CD25+ T cells and CD8+CD25− T cells from the spleens of WT mice and CD8+CD25− T cells from the spleens of DNIL-10R mice were isolated on day 6 after H5N1 infection and transferred into CD8 KO mice (5 × 105 CD8+CD25+ T cells and 1 × 107 CD8+ CD25− T cells per mouse) that were then immediately infected with H5N1 virus (day 0 of challenge). (B) Survival of mice (n = 10 per group) was monitored from day 4 to 16 after virus infection. Log-rank test for comparisons of survival curves between DNIL-10R CD8+CD25− T cells recipient mice and DNIL-10R CD8+CD25− T cells plus WT CD8+ Treg cells recipient mice, or between DNIL-10R CD8+CD25− T cells plus WT CD8+ Treg cells recipient mice and WT CD8+CD25− T cells plus WT CD8+ Treg cells recipient mice; n.s., p > 0.05. **, p < 0.01, log-rank test. (C) Viral load in mouse lungs were assayed on day 6 after virus infection (n = 5 mice per group). Data are presented as means ± SEM and are representative of four independent experiments. n.s., p > 0.05. *p < 0.05, unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Discussion

This is the first report to investigate the relationship of CD8+ Treg cells to antiviral immunity in H5N1 virus infection. We found that H5N1 virus-primed CD8+ Treg cells inhibited CD8+ T-cell immunity leading to a significantly higher level of mortality and greater viral load in the lung. The regulatory function of CD8+ Treg cells was found to be IL-10 dependent.

Our results are consistent with reports that the severity of highly pathogenic influenza virus infection correlates with an exuberant immune reaction in both humans and animal models. The characteristic features are a massive accumulation of macrophages and CD8+ T cells in the lungs and an overabundance of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the lungs and blood [29–33]. In this study of H5N1, we did not see an increase in the frequency of CD4+ Treg cells in PBMCs, spleen, or lung (Supporting Information Fig. 1A and B). In addition, the number of CD4+ Treg cells in BAL (Supporting Information Fig. 1C) was not increased. This contrasts with two reports that influenza H1N1 virus infection resulted in robust induction of a CD4+ Treg-cell response [34,35] and another demonstrating that Foxp3+CD4+ T cells had an important role during influenza H1N1 viral infection, protecting host tissues from immune-mediated damage [21]. The potential involvement of CD4+ Treg cells in the development of H5N1 virus induced pathology is still not ruled out and further experiments are needed to investigate the specific function of CD4+ Treg cells during H5N1 virus infection.

CD8+ Treg cells are known to express a range of cell surface markers, including CD122, CD25, GITR, CTLA-4, and PD-1 and various aspects of regulatory function have been found associated with the markers. Our finding that H5N1 virus primed CD8+ Treg cells significantly inhibited CD8+ T-cell proliferation via a cell contact independent mechanism contrasts with a report that CD8+CD25+ thymocytes that expressed GITR and CTLA-4 suppressed the proliferation of autologous CD25− T cells via a contact-dependent mechanism [36]. Our observation that H5N1 virus primed CD8+Foxp3+ Treg cells were almost all CD25+ or GITR+ and functioned via IL-10 may suggest a distinctive phenotype. This is not inconsistent with a report that CD8+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg-cell induction during primary SIV infection in cynomolgus macaques correlated with low CD4+ T-cell activation and high viral load [37]. Other reports indicate a range of phenotypes. For example, CD8+CD122+Foxp3− Treg cells effectively suppressed the proliferation and IFN-γ production of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells [38,39] and a novel allospecific regulatory CD8+PD1+ T cell induced by ICOS-B7h blockade in vivo could suppress allo-reactive CD4+ T cells [40].

IL-10 and TGF-β, recognized as antiinflammatory cytokines, can act on multiple cell types to regulate immune and inflammatory responses [41–44]. Although we found that the CD8+ Treg cells inhibited the proliferation of CD8+ T cells via the secreted IL-10, the mechanism has yet to be fully elucidated. IL-10-mediated inhibition of cell recruitment, activation, and/or production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines may be essential for regulating excess inflammation during H5N1 virus infection. In contrast to IL-10, TGF-β mRNA was expressed at low levels in H5N1 virus primed CD8+ Treg cells, indicating that the effects of TGF-β might not be important for CD8+ Treg-cell function. It is noted that IFN-γ also has tolerogenic effects; it could upregulate Foxp3 expression in CD4+ Treg cells, and has been implicated in suppression mediated by CD8+ Treg cells [45–47]. In addition, CD8+ Treg cells could directly kill the target cells during immune suppression by secreting killer molecules [48–50]. However, the transcript levels of IFN-γ, granzyme B, perforin, and fasl were not significantly different between CD8+ Treg cells and naive CD8+ T cells, suggesting that these molecules might not be mediators of H5N1 virus primed CD8+ Treg-cell effects.

The function of CD4+ Treg cells during influenza H1N1 virus infection is still unclear. Foxp3+CD4+ T cells have been reported to suppress innate immune pathology during influenza H1N1 infection [21]. However, another study demonstrated that depletion of CD4+ Treg cells with anti-CD25 antibodies did not alter the course of acute influenza H1N1 infection [35]. Although Foxp3+CD4+ T cells could be induced to suppress antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation and cytokine production [34], protection of host tissues from immune-mediated damage was not assessed. Much more data are needed to clarify the relevance of CD4+ Treg cells to clinical outcome during H1N1 and H5N1 virus infections. The function of CD8+ Treg cells during influenza A virus infection is also unclear. Although we found that the induced CD8+ Treg cells suppressed CD8+ T-cell responses and caused worse disease outcome during H5N1 virus infection, we did not assess the effect of CD8+ Treg cells on innate immune response. Since Mx1 represents a key component of the murine innate immune system, high levels of IFN-β and Mx-1 in cells from the lungs of CD8+ Treg cells recipients may indicate stronger innate immune responses. We may in future use lymphocyte-deficient mice as hosts to detect the function CD8+ Treg cells on the innate immune responses. In addition, since H5N1-primed CD8+ Treg cells did not suppress CD4+ T-cell responses in the lung, we did not test whether CD8+ Treg cells could inhibit CD4+ T-cell proliferation and cytokine production in vitro and this remains to be tested.

CD8+ Teff cells have been suggested to produce IL-10 to fine-tune the extent of lung inflammation and injury associated with acute H1N1 influenza virus infection. Blockade of IL-10 in vivo resulted in enhanced lung inflammation, elevated expression of multiple cytokines and chemokines in the infected lungs, and increased mortality, but with no effect on virus titer or clearance. In addition, these CD8+ Teff cells expressed high amounts of T-bet but not Foxp3 [22]. In our lethal H5N1 influenza virus infection model, IL-10+Foxp3+ CD8+ T cells and IL-10+Foxp3− CD8+ T cells were both induced. IL-10+Foxp3+ CD8+ T cells suppressed CD8+ Teff cell responses through production of IL-10 and increased the mortality of the infected mice. IL-10+Foxp3− CD8+ T cells might also have regulatory functions to control lung inflammation and injury associated with influenza infection but this was not tested here. There could be preferential induction of IL-10+Foxp3+ CD8+ T cells in our H5N1 virus infection model compared to the H1N1 virus infection model, perhaps due to differences in the viral strain or inoculum size, but further studies are needed to clarify this point.

Overall, our data reveal a previously unrecognized function of CD8+ Treg cells in providing regulatory function during H5N1 virus infection. Understanding the process of IL-10 production by the CD8+ Treg cells and the function of AIV-induced CD8+ Treg cells may provide insight into the pathogenesis of infection and might possibly lead to better vaccine design strategies to fight influenza pandemics.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice at 6–8 weeks old were purchased from the Animal Institute of Chinese Medical Academy (Beijing, China). Foxp3-GFPtg mice (BALB/c-C.Cg-Foxp3tm2Tch/J) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). CD8 KO mice (C57BL/6 background), IL-10-GFPtg (C57BL/6 background), and DNIL-10R mice (C57BL/6 background) were kindly provided by Zhinan Yin (Nankai University, Tianjin, China) and Richard Flavell (Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA). All mice were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of China Agricultural University and housed with pathogen-free food and water under 12 h light cycle condition.

Reagents

Fluorescently labeled anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies used for flow cytometry were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-IL-10 mAb and isotype control antibodies were purchased from BD Bioscience Pharmingen. Influenza virus nucleoprotein (NP) NP366–374 peptide representing the CD8+ T-cell epitope (ASNENMETM) was synthesized by GL Biochem Co. The conservative NP366–374 peptide of H5N1, A/Chicken/Henan/1/04, is ASNENMEAM. MagCellect Mouse CD4+CD25+ T-cell Isolation Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), MagCellect Mouse CD8+ T-cell Isolation Kit (R&D Systems), EasySep® Mouse Naïve CD8+ T-cell Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) and EasySep® CD11c Positive Selection Kit (STEMCELL Technologies) were purchased.

Viral infection

Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus, (HPAIV, H5N1, A/Chicken/Henan/1/04) was maintained in a BSL-3 facility (China Agriculture University, Beijing, China). Mice were infected with HPAIV by intranasal (i.n.) inoculation of 50 μL of virus (10 LD50) in PBS on day 0. The dose is based on the original titrations conducted at the time the batch was produced. Although the titers drift down overtime, the viral doses used in this study were based on the original titration. This viral infection caused death of all the unimmunized mice within 7–12 days.

Flow cytometric analysis

PBMCs, splenic cells, lung cells, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells were isolated on days 3 and 6 from mice infected by H5N1 virus. Surface staining of CD4, CD8, CD25, GITR, CTLA-4, and PD-1 was performed. Samples were analyzed by an FACSCalibur. Splenic cells were isolated on day 6 after viral infection and stimulated with 10 μg/mL NP peptide in the presence of brefeldin A (5 μg/mL) for 6 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Collected cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich). For immunostaining of cytoplasmic IL-10 and Foxp3 and surface CD8, the appropriate concentrations of fluorescently labeled anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies were added to permeabilized cells for 30 min on ice followed by washing twice with cold PBS [51–53]. Samples were analyzed by an FACSCalibur.

Isolation of CD8+CD25+, CD8+CD25−, and naïve CD8+ T cells

Splenic cells were isolated on day 6 after viral infection and purified by using MagCellect Mouse CD4+CD25+, CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer∼s protocol. CD8+ T cells were first purified using the CD8 kit and then CD8+CD25+ T cells were obtained from the purified CD8+, and CD8+CD25− T cells were from the unbound cells. Naïve CD8+ T cells were purified by using EasySep® Mouse naïve CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit. Purities of T cells were approximately 90–95% analyzed by the FACSCalibur.

Real-time PCR for cytokines

Splenic CD8+CD25+ T cells were isolated on day 6 after viral infection. Total RNA was extracted from these cells using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Real-time PCR for Foxp3, IL-10, TGF-β, IFN-γ, perforin, Granzyme B, fasl, and GAPDH was performed. Total RNA of lung cells on day 3 or 6 after viral infection was extracted to perform real-time PCR for IFN-β and Mx-1. The reaction was run on an ABI 7500 and data analysis was performed using 7500 software v2.0 (ABI). The following primers were used for the amplification of target transcripts: GAPDH forward (5′-GGTTGTCTCCTGCGACTTCA-3′) and reverse (5′-GGGTGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTA-3′), Foxp3 forward (5′-GGCGAAAGTGGCAGAGAGGTAT-3′) and reverse (5′-AAGACCCCAGTGGCAGCAGAA-3′), Il-10 forward (5′-GGTTGCCAAGCCTTATCGGA-3′) and reverse (5′-ACCTGCTCCACTGCCTTGCT-3′), Tgf-β forward (5′-GCAACATGTGGAACTCTACCAGAA-3′) and reverse (5′-GACGTCAAAAGACAGCCACTCA-3′), Ifn-γ forward (5′-GAAAGCCTAGAAAGTCTGAATAACT-3′) and reverse (5′-ATCAGCAGCGACTCCTTTTCCGCT-3′), perforin forward (5′-GATGTGAACCCTAGGCCAGA-3′) and reverse (5′-GGTTTTTGTACCAGGCGAAA-3′), Granzyme B (GZ-B) forward (5′-GGATATAAGGATGGTTCACC-3′) and reverse (5′-CACCTGTCCTAGAGCAATCC-3′), fasl forward (5′-TGAATTACCCATGTCCCCAG-3′) and reverse (5′-AAACTGACCCTGGAGGAGCC-3′), Ifn-β forward (5′-AGCTCCAAGAAAGGACGAACAT-3′) and reverse (5′-GCCCTGTAGGTGAGGTTGATCT-3′), Mx-1 forward (5′-TGCAGAGGTCAGCAGGACATC-3′) and reverse (5′-GGCAGTTTGGACCATCTCTGAA-3′).

Viral RNA determination

Total RNA was prepared from 10 mg lung homogenized and extracted in Trizol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer∼s instruction. DNase I treated RNA (2 μg) was used to reverse transcribe into cDNA using a set of universal primers for influenza A virus [54] as follows: forward (5′-CGCAGTATTCAGAAGAAGCAAGAC-3′), reverse (5′-TCCATAAGGATAGACCAGCTACCA-3′). Real-time PCR was performed to amplify the hemagglutinin (HA) gene of H5N1 influenza virus using SYBR® PrimeScript® RT-PCR Kit (TaKaRa, Japan). The reaction was run on an ABI 7500 and data analysis was performed using 7500 software v2.0 (ABI). The copy number of the HA gene was calculated by using an HA-containing plasmid of known concentration as a standard.

T cells adoptive transfer

Splenic CD8+CD25+, CD8+CD25−, and CD8+ T cells were purified on day 6 after viral infection. The cells were adoptively transferred intravenously into normal Balb/c or C57BL/6 mice at 1 × 105 CD8+CD25+ T cells or 5 × 105 CD8+CD25+ T cells, 1 × 107 CD8+CD25− T cells and 1 × 107 CD8+ T cells per recipient mouse.

Isolation of CD11c+ cells

Splenic cells were isolated on day 6 after viral infection and purified by using EasySep® Mouse CD11c Positive Selection Kit (STEMCELL Technologies) according to the manufacturer∼s protocol. Purity was about 85%.

Detection of anti-H5N1 antibody

Anti-H5N1 antibody content of serum samples was measured by ELISA as described previously [53]. On day 8 after H5N1 virus infection, sera were collected and ELISA was performed in a 96-well polystyrene microtiter plate coated with inactivated H5N1 virus. Following the blockage with 3% of BSA for 1 h, goat anti-mouse IgG Ab (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) diluted 1000-fold was added. Ten milligrams of TMB tablet (Sigma) was dissolved in 0.025 M phosphate-citrate buffer and subsequently added to each well for color development. After the reaction was stopped by 2 M H2SO4, the plate was read with a plate reader at 450/620 nm. The antibody titers were determined by the absolute ratio of OD values of post/naive sera at cut-off value 2.1.

T-cell proliferation assays

Splenic CD8+CD25+, CD8+ CD25− T cells, and CD11c+ cells were purified on day 6 after viral infection. CD8+ CD25− T cells were labeled with carboxyl fluorescent succinimidyl ester (CFSE, 1.25 μg/mL in PBS) for 5 min at room temperature. After two washes with RPMI medium or PBS, 2 × 105 CD8+CD25+ T cells, and 5 × 104 CD11c+ cells were stimulated with NP366–374 peptide (ASNENMETM, 10 μg/mL). After 5 days in culture, CFSE intensity was determined by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as means ± SEM. Student∼s t-test analysis was used for data analysis. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the National High-Tech 863 Project of China (2010AA022907), Scientific Technology Development Foundation of Shanghai (09DZ1908602), National Major Anti-infectious Disease Program of China (2012ZX10002002), Shanghai Avian Influenza Prevention and Control of Joint Research Projects, and Fudan University Initiative Projects of Avian Influenza Prevention and Controls. We thank Zhinan Yin and Dr. Richard Flavell (Yale School of Medicine) for kindly providing CD8 KO mice, IL-10-GFPtg mice, DNIL-10R mice in the study, and Dr. Douglas Lowrie for his critical review of this manuscript. We would also like to thank Dr.Yanxin Hu, Dr. Jane QL Yu, Mr. Xianghua Shi, and Mr. Zhonghuai He for their technical assistance.

Glossary

- AIV

avian influenza virus

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavages

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re-organized for online delivery, but are not copy-edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Figure S1. Detection of CD4 Treg in Foxp3-GFPtg mice during H5N1 viral infection.

Figure S2. Induction of CD8 Treg in C57BL/6 mice during H5N1 viral infection.

Figure S3. Analysis purified CD8+CD25+ T cells.

Figure S4. Detection of DNIL-10R mice.

Peer review correspondence

References

- 1.Beigel JH, Farrar J, Han AM, Hayden FG, Hyer R, de Jong MD, Lochindarat S, et al. Avian influenza AH5N1) infection in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1374–1385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gambotto A, Barratt-Boyes SM, de Jong MD, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. Human infection with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus. Lancet. 2008;371:1464–1475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham MB, Braciale TJ. Resistance to and recovery from lethal influenza virus infection in B lymphocyte-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:2063–2068. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szretter KJ, Gangappa S, Belser JA, Zeng H, Chen H, Matsuoka Y, Sambhara S, et al. Early control of H5N1 influenza virus replication by the type I interferon response in mice. J. Virol. 2009;83:5825–5834. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02144-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedrick SM. The acquired immune system: a vantage from beneath. Immunity. 2004;21:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kagi D, Ledermann B, Burki K, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity and their role in immunological protection and pathogenesis in vivo. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1996;14:207–232. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claas EC, Osterhaus AD, van Beek R, De Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Senne DA, Krauss S, et al. Human influenza A H5N1 virus related to a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Lancet. 1998;351:472–477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Subbarao K, Klimov A, Katz J, Regnery H, Lim W, Hall H, Perdue M, et al. Characterization of an avian influenza AH5N1) virus isolated from a child with a fatal respiratory illness. Science. 1998;279:393–396. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuen KY, Chan PK, Peiris M, Tsang DN, Que TL, Shortridge KF, Cheung PT, et al. Clinical features and rapid viral diagnosis of human disease associated with avian influenza A H5N1 virus. Lancet. 1998;351:467–471. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)01182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisman DN. Hemophagocytic syndromes and infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2000;6:601–608. doi: 10.3201/eid0606.000608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Headley AS, Tolley E, Meduri GU. Infections and the inflammatory response in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Chest. 1997;111:1306–1321. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.5.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung CY, Poon LL, Lau AS, Luk W, Lau YL, Shortridge KF, Gordon S, et al. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in human macrophages by influenza AH5N1) viruses: a mechanism for the unusual severity of human disease? Lancet. 2002;360:1831–1837. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Jong MD, Simmons CP, Thanh TT, Hien VM, Smith GJ, Chau TN, Hoang DM, et al. Fatal outcome of human influenza AH5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat. Med. 2006;12:1203–1207. doi: 10.1038/nm1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shevach EM. Mechanisms of foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity. 2009;30:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudensky AY, Campbell DJ. In vivo sites and cellular mechanisms of T reg cell-mediated suppression. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:489–492. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belkaid Y. Regulatory T cells and infection: a dangerous necessity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:875–888. doi: 10.1038/nri2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belkaid Y, Tarbell K. Regulatory T cells in the control of host-microorganism interactions (*) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:551–589. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouse BT, Sarangi PP, Suvas S. Regulatory T cells in virus infections. Immunol. Rev. 2006;212:272–286. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sehrawat S, Suvas S, Sarangi PP, Suryawanshi A, Rouse BT. In vitro-generated antigen-specific CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells control the severity of herpes simplex virus-induced ocular immunoinflammatory lesions. J. Virol. 2008;82:6838–6851. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00697-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antunes I, Kassiotis G. Suppression of innate immune pathology by regulatory T cells during influenza A virus infection of immunodeficient mice. J. Virol. 2010;84:12564–12575. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01559-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun J, Madan R, Karp CL, Braciale TJ. Effector T cells control lung inflammation during acute influenza virus infection by producing IL-10. Nat. Med. 2009;15:277–284. doi: 10.1038/nm.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Izcue A, Coombes JL, Powrie F. Regulatory T cells suppress systemic and mucosal immune activation to control intestinal inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 2006;212:256–271. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yagi H, Nomura T, Nakamura K, Yamazaki S, Kitawaki T, Hori S, Maeda M, et al. Crucial role of FOXP3 in the development and function of human CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells. Int. Immunol. 2004;16:1643–1656. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paget C, Ivanov S, Fontaine J, Blanc F, Pichavant M, Renneson J, Bialecki E, et al. Potential role of invariant NKT cells in the control of pulmonary inflammation and CD8+ T cell response during acute influenza A virus H3N2 pneumonia. J. Immunol. 2011;186:5590–5602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamanaka M, Huber S, Zenewicz LA, Gagliani N, Rathinam C, O∼Connor W, Jr, Wan YY, et al. Memory/effector (CD45RB(lo)) CD4 T cells are controlled directly by IL-10 and cause IL-22-dependent intestinal pathology. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1027–1040. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huber S, Gagliani N, Esplugues E, O∼Connor W, Jr, Huber FJ, Chaudhry A, Kamanaka M, et al. Th17 cells express interleukin-10 receptor and are controlled by Foxp3 and Foxp3+ regulatory CD4+ T cells in an interleukin-10-dependent manner. Immunity. 2011;34:554–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baskin CR, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Tumpey TM, Sabourin PJ, Long JP, Garcia-Sastre A, Tolnay AE, et al. Early and sustained innate immune response defines pathology and death in nonhuman primates infected by highly pathogenic influenza virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:3455–3460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813234106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cilloniz C, Shinya K, Peng X, Korth MJ, Proll SC, Aicher LD, Carter VS, et al. Lethal influenza virus infection in macaques is associated with early dysregulation of inflammatory related genes. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000604. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kash JC, Tumpey TM, Proll SC, Carter V, Perwitasari O, Thomas MJ, Basler CF, et al. Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2006;443:578–581. doi: 10.1038/nature05181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maines TR, Szretter KJ, Perrone L, Belser JA, Bright RA, Zeng H, Tumpey TM, et al. Pathogenesis of emerging avian influenza viruses in mammals and the host innate immune response. Immunol. Rev. 2008;225:68–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peiris JS, Cheung CY, Leung CY, Nicholls JM. Innate immune responses to influenza A H5N1: friend or foe? Trends Immunol. 2009;30:574–584. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Betts RJ, Prabhu N, Ho AW, Lew FC, Hutchinson PE, Rotzschke O, Macary PA, et al. Influenza A virus infection results in a robust, antigen-responsive, and widely disseminated Foxp3+ regulatory T cell response. J. Virol. 2012;86:2817–2825. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05685-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Betts RJ, Ho AW, Kemeny DM. Partial depletion of natural CD4CD25 regulatory T cells with anti-CD25 antibody does not alter the course of acute influenza A virus infection. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cosmi L, Liotta F, Lazzeri E, Francalanci M, Angeli R, Mazzinghi B, Santarlasci V, et al. Human CD8+CD25+ thymocytes share phenotypic and functional features with CD4+CD25+ regulatory thymocytes. Blood. 2003;102:4107–4114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karlsson I, Malleret B, Brochard P, Delache B, Calvo J, Le Grand R, Vaslin B. FoxP3 +CD25+ CD8+ T-cell induction during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in cynomolgus macaques correlates with low CD4+ T-cell activation and high viral load. J. Virol. 2007;81:13444–13455. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01466-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rifa∼i M, Kawamoto Y, Nakashima I, Suzuki H. Essential roles of CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells in the maintenance of T cell homeostasis. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:1123–1134. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rifa∼i M, Shi Z, Zhang SY, Lee YH, Shiku H, Isobe K, Suzuki H. CD8+CD122 +regulatory T cells recognize activated T cells via conventional MHC class I-alphabeta TCR interaction and become IL-10-producing active regulatory cells. Int. Immunol. 2008;20:937–947. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Izawa A, Yamaura K, Albin MJ, Jurewicz M, Tanaka K, Clarkson MR, Ueno T, et al. A novel alloantigen-specific CD8+PD1+ regulatory T cell induced by ICOSB7h blockade in vivo. J. Immunol. 2007;179:786–796. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O∼Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li MO, Wan YY, Sanjabi S, Robertson AK, Flavell RA. Transforming growth factor-beta regulation of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:99–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubtsov YP, Rudensky AY. TGFbeta signalling in control of T-cell-mediated self-reactivity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:443–453. doi: 10.1038/nri2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang M, Jin W, Chang JH, Xiao Y, Brittain GC, Yu J, Zhou X, et al. The ubiquitin ligase Peli1 negatively regulates T cell activation and prevents autoimmunity. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:1002–1009. doi: 10.1038/ni.2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J. Yin and yang interplay of IFN-gamma in inflammation and autoimmune disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:871–873. doi: 10.1172/JCI31860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng G, Gao W, Strom TB, Oukka M, Francis RS, Wood KJ, Bushell A. Exogenous IFN-gamma ex vivo shapes the alloreactive T-cell repertoire by inhibition of Th17 responses and generation of functional Foxp3 +regulatory T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008;38:2512–2527. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seo SK, Choi JH, Kim YH, Kang WJ, Park HY, Suh JH, Choi BK, et al. 4-1BB-mediated immunotherapy of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Med. 2004;10:1088–1094. doi: 10.1038/nm1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Badovinac VP, Tvinnereim AR, Harty JT. Regulation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell homeostasis by perforin and interferon-gamma. Science. 2000;290:1354–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5495.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stepp SE, Dufourcq-Lagelouse R, Le Deist F, Bhawan S, Certain S, Mathew PA, Henter JI, et al. Perforin gene defects in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Science. 1999;286:1957–1959. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith TR, Kumar V. Revival of CD8+ Treg-mediated suppression. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zou Q, Yao X, Feng J, Yin Z, Flavell R, Hu Y, Zheng G, et al. Praziquantel facilitates IFN-gamma-producing CD8+ T cells (Tc1) and IL-17-producing CD8+ T cells (Tc17) responses to DNA vaccination in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin H, Kang Y, Zhao L, Xiao C, Hu Y, She R, Yu Y, et al. Induction of adaptive T regulatory cells that suppress the allergic response by coimmunization of DNA and protein vaccines. J. Immunol. 2008;180:5360–5372. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zou Q, Hu Y, Xue J, Fan X, Jin Y, Shi X, Meng D, et al. Use of Praziquantel as an adjuvant enhances protection and Tc-17 responses to kill H5N1 virus vaccine in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu Y, Jin Y, Han D, Zhang G, Cao S, Xie J, Xue J, et al. Mast cell-induced lung injury in mice infected with H5N1 influenza virus. J. Virol. 2012;86:3347–3356. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06053-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Detection of CD4 Treg in Foxp3-GFPtg mice during H5N1 viral infection.

Figure S2. Induction of CD8 Treg in C57BL/6 mice during H5N1 viral infection.

Figure S3. Analysis purified CD8+CD25+ T cells.

Figure S4. Detection of DNIL-10R mice.

Peer review correspondence