Abstract

Purpose.

Mutations in the cilia-centrosomal protein of centrosomal protein of 290 kDa (CEP290) result in severe ciliopathies, including autosomal recessive early onset childhood blindness disorder Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA). The Cep290rd16 (retinal degeneration 16) mouse model of CEP290-LCA exhibits accumulation of CEP290-interacting protein Raf-1 kinase inhibitory protein (RKIP) prior to onset of retinal degeneration (by postnatal day P14). We hypothesized that reducing RKIP levels in the Cep290rd16 mouse will delay or improve retinal phenotype.

Methods.

We generated double mutant mice by combining the Cep290rd16 and Rkipko alleles (Cep290rd16:Rkip+/ko and Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko). Retinal function was assessed by ERG and retinal morphology and protein trafficking were assessed by histology, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and immunofluorescence analysis. Cell death was examined by apoptosis.

Results.

Prior to testing our hypothesis, we examined ERG and retinal morphology of Rkipko/ko mice and did not find any detectable differences compared with wild-type mice. The Cep290rd16:Rkip+/ko mice exhibited similar retinopathy as Cep290rd16; however, Cep290rd16: Rkipko/ko double knockout mice demonstrated a substantial improvement (>9-fold) in photoreceptor function and structure at P18 as of Cep290rd16 mice. We consistently detected transient preservation of photoreceptors at P18 and polarized trafficking of opsins to sensory cilia in the double mutant mice; however, retinal degeneration ensued by P30.

Conclusions.

Our studies implicate CEP290-RKIP pathway in CEP290-retinal degeneration and suggest that targeting RKIP levels can delay photoreceptor degeneration, assisting in extending the time-window for treating such rapidly progressing blindness disorder.

Keywords: CEP290, RKIP, retina, photoreceptor degeneration, blindness

This manuscript shows that CEP290-associated fast progressing early-onset retinal phenotype in rd16 mouse can be delayed by reducing the levels of one of its interacting proteins, RKIP. The work provides a platform to design intermediates that can be supplemented with other therapeutic strategies.

Introduction

Cilia are microtubule-based membrane extensions that act as antenna to sense the extracellular environment. They are formed by docking of the mother centriole (basal body) at the apical plasma membrane followed by recruitment of multiprotein complexes, including small GTPases and microtubule motor proteins. Microtubules extend from the basal body into a short structure called the transition zone, which acts as a “gatekeeper” by forming Y-linkers that connect the microtubules to the plasma membrane. Cilia then extend further into the extracellular milieu in the form of axoneme.1–6

Photoreceptors are polarized sensory neurons that develop a sensory cilium in the form of photosensory outer segment (OS).2,7–10 The OS consists of stacks of membranous discs that are periodically shed and renewed daily. This process involves enormous polarized protein trafficking from the inner segment (where protein synthesis takes place) to the OS via a narrow transition zone (or connecting cilium). The OS is a hub for opsin and other proteins involved in phototransduction cascade. Even subtle defects in the stringently regulated protein and membrane trafficking machinery result in photoreceptor degeneration and blindness.11–15

Centrosomal protein of 290 kDa (CEP290) is a cilia-centrosomal protein involved in regulating cilia formation and protein trafficking in photoreceptors and other cell types.16–19 Mutations in CEP290 result in a range of defects, likely dependent upon the extent of loss of CEP290 function. Mutations in CEP290 are implicated in perturbing the gatekeeping function of the transition zone of cilia18,20–22 and are frequently (20%–25%) associated with childhood blindness disorder, Leber congenital amaurosis type 10 (LCA10; MIM 611755).23–26 Also, CEP290 mutations are relatively common in other syndromic ciliopathies with variable and systemic clinical manifestations, such as Joubert syndrome, Meckel-Gruber syndrome, and Bardet-Biedl syndrome.5,6,27

Animal models of CEP290 mutations offer crucial insights into its function and associated pathogenesis. A naturally occurring cat model of CEP290 mutation was reported earlier, which exhibits a relatively delayed onset retinal defect.28 We previously reported the characterization of rd16 (retinal degeneration 16) mouse carrying an in-frame deletion in Cep290.20 This mouse exhibits early onset severe photoreceptor dysfunction and degeneration, starting as early as postnatal day P14. The mutant CEP290 protein is still expressed at detectable levels in the mutant mouse. In addition to retinal degeneration, the Cep290rd16 mouse exhibits other sensory deficits, such as anosmia and hearing abnormalities.20,22 However, no other systemic ciliopathies, such as kidney or cerebellar defects, were observed.

In addition to providing valuable insights into the function of CEP290, the Cep290rd16 mouse is an excellent platform to test therapeutic strategies. We had earlier reported that CEP290 interacts with Raf-1 Kinase Interacting Protein (RKIP) and that this interaction is perturbed in the Cep290rd16 mouse retina.18 Moreover, there is aberrant accumulation of RKIP in photoreceptors prior to onset of retinal degeneration. These observations suggest that accumulation of RKIP is associated with the pathogenesis in the rd16 mouse. Therefore, we hypothesized that modulating RKIP levels in the Cep290rd16 mouse can mitigate retinal degeneration. In this report, we assessed the effect of loss of RKIP on the progression of photoreceptor dysfunction and degeneration in the Cep290rd16 mouse by generating and characterizing double mutant mice. Our studies provide a novel tool to design supplemental therapies for successfully rescuing rapidly progressing retinal degeneration due to CEP290 mutations.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were performed with prior approval and in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulations. Mice were maintained and bred with unrestricted access to water and food in the same light conditions (10–15 lux), and in a 12-hour light and 12-hour dark cycle. Both Cep290rd16 20 and Rkipko/ko (a gift of Kam Yeung, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA)29 mice on C57BL6/J background were used to generate double-mutant Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko, and single heterozygote mutant of Rkip, Cep290rd16:Rkip+/ko. The mutations were confirmed by both genotyping PCR and retina specific immunoblot using previously described procedures.20,29 The list of primers used for the characterization of mouse models with their primer annealing temperature and expected PCR product size can be made available upon request.

Immunoblotting

Mice (n = 5) eyes were enucleated and the retinas were lysed and sonicated in radio immunoprecipitation assay buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA) with protease inhibitors (Roche, Inc., Nutley, NJ, USA). The protein extracts were collected by centrifugation at 13,000g for 15 minutes at 4°C and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, as described.14

Antibodies

Commercial antibodies included anti-RKIP (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA, USA), anti-rhodopsin (Millipore Corp.), anti-β-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA), and anti-CEP290 (Bethyl Labs, Montgomery, TX, USA). Anti-M opsin was a gift of Cheryl M. Craft.42 Secondary antibodies included AlexaFluor 488 and AlexaFluor 546 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA).

ERG, Histology, and Immunofluorescence

Analyses with ERG were performed using a commercial diagnostic technique (Espion Diagnosys LLC, Cambridge, UK) as described previously.14 For histology and immunofluorescence, mouse eyes were enucleated, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C, ethanol-dehydrated in serial gradients, and embedded as paraffin blocks. Sections of 7-μM thickness were cut along the vertical meridian of each eyeball and stained with H&E.

For immunofluorescence staining, mouse eyes were fixed in 4% PFA, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose overnight and frozen in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Tissue-Tek; Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA); 20-μM sections were used for staining as described previously.14 All images were captured using a commercial imaging system (Leica DMI6000B; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Morphometric Analysis

The morphometric analysis of outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness in Cep290rd16 and Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko was performed as described.14 Sections of H&E along the optic nerve head (ONH) plane from five different mice were used for measurements.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

For ultrastructural analysis using TEM, mouse eyes were treated and as described.14 Briefly, eyes were enucleated and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) overnight at 4°C. The eyecups were then washed three times in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide/0.1 M cacodylate buffer, ethanol dehydrated, and then finally embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were cut along the vertical meridian of eyeball with ONH using an ultramicrotome (Leica Reichart-Jung; Leica Microsystems) and stained with 2% uranyl acetate and 4% lead citrate. The resulting retina sections were then visualized with a TEM (Philips CM-10; Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands), coupled with a charge-coupled device digital camera (Gatan Erlangshen 785; Gatan, Inc., Warrendale, PA, USA).

TUNEL Staining

Staining with TUNEL was performed using a commercial kit (ApopTag Plus fluorescein In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA). Briefly, paraffin sections were deparaffinized, pretreated with proteinase K, stained using fluorescein conjugated digoxigenin/antidigoxigenin system, and counterstained using DAPI. The mounted sections were then imaged and quantified for apoptotic cells.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were carried out using graphing software (GraphPad Prism Version 6.0; GraphPad, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and when statistical significance was seen by ANOVA, the Tukey's comparison of means was used to find significant group differences. Statistical significance was set at minimal value of P < 0.05. All graphical representations of data were also generated in graphing software (GraphPad, Inc.).

Results

Retinal Function in Rkipko/ko Mice

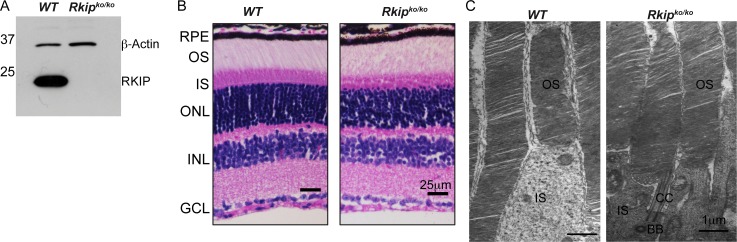

We first evaluated the expression of RKIP protein in the Rkipko/ko 29 mouse retina. While we detected the expected ∼25 kDa anti-RKIP immunoreactive band in wild-type retinal extracts, the Rkipko/ko retinal extract did not exhibit an immunoreactive band (Fig. 1A). To test the effect of ablation of Rkip on retinal morphology and function, we assessed retinal histology and photoreceptor function of the Rkipko mice. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of retinal sections or transmission electron microscopy (TEM) did not reveal any differences in the development of the retinal layers in the mutant mice compared with age-matched wild-type mice (Figs. 1B, 1C). Consistently, ERG analysis of rod and cone photoreceptor function also did not reveal any detectable differences between Rkipko and wild-type mice (data not shown). Overall, these results show that ablation of Rkip has no detectable effect on retinal development and function.

Figure 1.

Characterization of Rkipko/ko mice. A. Immunoblot analysis of retinal extracts (30 μg) was performed using anti-RKIP or anti-β-actin antibody (loading control). Molecular mass markers are shown on the left in kDa. (B, C). Histological (B) and TEM (C) analysis of WT and Rkipko/ko retina was performed as described in the “Materials and Methods” section. BB, basal body; CC, connecting cilium; GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer. Scale bars: 25 μm (B), 1 μm (C).

Characterization of Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko Double-Mutant Mice at P18

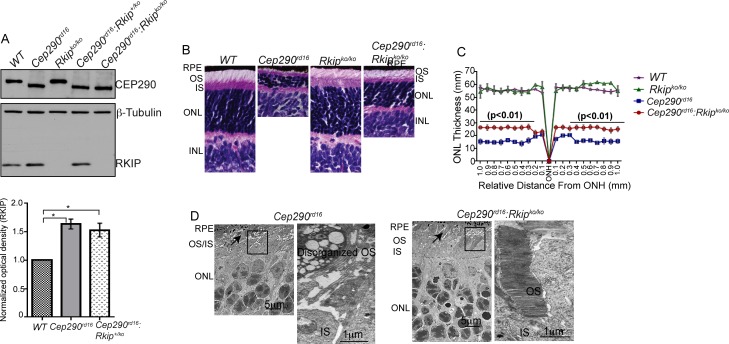

We then generated double-mutant mice by breeding Cep290rd16 mice with Rkipko/ko mice. Both mouse strains are on C57BL6/J background. Immunoblot analysis of the mutant mouse retinas validated the expression of the deleted variant (shorter protein band) of CEP290 in the Cep290rd16 as well as Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko double-mutant mice (Fig. 2A). As predicted, RKIP protein expression was not detected in the Rkipko/ko and double-mutant mice (Fig. 2A). Notably, no change in RKIP protein levels was detected in Cep290rd16:Rkip+/ko mice compared with Cep290rd16 mice; and as predicted,18 the RKIP protein levels are significantly increased in these mice compared with the wild-type (WT) mice (Fig. 2A; lower panel).

Figure 2.

Characterization of double-knockout mice. (A) Immunoblot analysis of retinal extracts (30 μg) of mice of indicated genotypes was performed using antibodies against CEP290, RKIP and β-tubulin (loading control); RKIP immunoreactive band is not detected in the Rkipko/ko lanes. Also, predicted shorter deleted variant of CEP290 is detected in Cep290rd16 retinal extract. Lower panel shows quantitative analysis of the band intensity of RKIP in the Cep290rd16 and Cep290rd16:Rkip+/ko mouse retina relative to WT. (B) Histological analysis of WT and mutant retinas of indicated genotypes was performed to assess retinal morphology. Thinning of the ONL was observed in the Cep290rd16 retina, whereas improved thickness of the ONL is detected in the Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko retina. (C) Morphometric analysis of retinas, also showed an overall statistically significant (P < 0.01) improvement in the thickness of the ONL. Retinas from five different mice of each genotype were analyzed in this experiment. (D) TEM analysis of Cep290rd16 (left panel) and Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko (right panel) mice was performed to assess detailed photoreceptor morphology. Arrow in upper panel points to indistinguishable OS and IS while arrow in lower panel depicts organized OS and IS. Inset shows disorganized OS in Cep290rd16 photoreceptors and correctly developed and stacked OS discs in Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko retina. Scale bars: 5 and 1 μm (inset).

Further analysis of the double-mutant mice showed that loss of RKIP in the Cep290rd16 mice results in relative preservation of retinal morphology by P18. Histological analysis showed increase in the thickness of photoreceptor outer nuclear layer (ONL; Fig. 2B). Morphometric analysis further validated these findings. It revealed an approximately 2-fold increase in the thickness of the ONL in the double-mutant mice compared with Cep290rd16 mice (Fig. 2C; P < 0.01). The WT and Rkipko/ko mice showed comparable thickness of the ONL (Fig. 2C). We then performed ultrastructural analysis of photoreceptors of the different mutant mice. As shown in Figure 2D, Cep290rd16 retina exhibits disorganized OS and indistinguishable OS and inner segment (IS) layers, whereas Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko double-mutant retina shows a well-formed OS structure with stacked discs and distinguishable IS.

Functional Analysis of Double-Mutant Mice

We next tested the effect of ablation of Rkip in Cep290rd16 mice on the function of photoreceptors. Measurement of ERG responses revealed improved rod photoreceptor function in dark-adapted conditions at P18 in the double-mutant mice compared with Cep290rd16. As shown in Figure 3, scotopic (dark-adapted) A-wave amplitude revealed >9-fold increased response (P < 0.0001) while B-wave increased by ∼2-fold (P < 0.0001). No improvement was detected in Cep290rd16:Rkip+/ko indicating that complete loss of RKIP is important for the observed improvement in Cep290rd16 mouse retina. Interestingly, measurement of photopic B-wave responses at P18 did not reveal an improvement in the double-mutant mice.

Figure 3.

Electroretinography of mutant mice at P18. Scotopic (dark-adapted) and photopic (light-adapted) ERG was performed in mice of indicated genotypes. Light-adapted ERGs were recorded using a background white light illumination of 34 cd/m2 for 8 minutes. A single step stimulus of 10 cd/m2 was used and an average from 20 trials was presented as photopic response. Statistically significant improvement in scotopic A- and B-wave amplitudes was detected in Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko mice compared with Cep290rd16 mice. NS, statistically nonsignificant. *P < 0.0001.

Protein Trafficking in Double-Mutant Mice

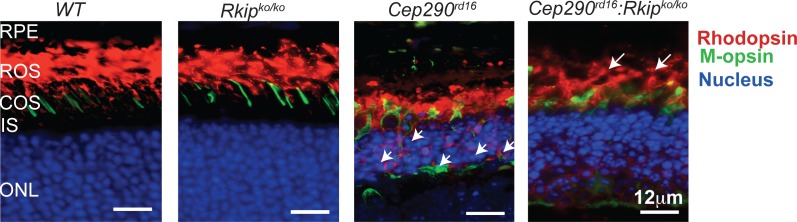

We then assessed the effect of loss of RKIP in Cep290rd16 on the trafficking of opsins to OS. While almost complete mislocalization of rhodopsin and cone opsin was detected in the Cep290rd16 retina at P18, the double-mutant mice exhibited improved trafficking of the opsins to the OS (Fig. 4). As predicted, WT and Rkipko/ko mice did not show a mislocalization of opsins.

Figure 4.

Trafficking of OS proteins at P18. Cryosections from WT and mutant mice were stained for rhodopsin (red; rods) and M-opsin (green; cones). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). Arrows indicate bulk of rhodopsin signal in the OS of Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko mice, whereas small arrows indicate considerable rhodopsin mislocalization in the ONL of Cep290rd16 mice. Rkipko/ko retina did not exhibit a difference in opsin trafficking as compared to WT. Scale bars: 12 μm.

Retinal Phenotype of Double-Mutant Mice at P30

We next tested whether the preservation of retinal structure and function is stable over longer time periods in the double-mutant mice. To this end, we performed histological and ERG analyses of the Cep290rd16 and Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko mice at age 1 month (P30). Surprisingly, we detected deterioration in retinal morphology and function (Fig. 5). Intriguingly, although Cep290rd16 showed a considerable decline in photopic B-wave amplitude by P30, ∼20% increase in the B-wave amplitude was detected in Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko at the same age (Fig. 5A). The increase in the B-wave amplitude was transient as shown by decrease in the signal at P60 in the double knockout mice, which was comparable with the B-wave amplitude of Cep290rd16 at the same age. Rhodopsin-positive photoreceptors with relatively improved trafficking were still detectable in the double-mutant mice compared with Cep290rd16 at P30, indicating overall slower degeneration in the Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko mice (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Characterization of mutant mice at P30 and P60. Analysis of ERG (A) and immunofluorescence analysis (B) were performed as described in the Materials and Methods section. Rhodopsin (red) and M-opsin (green) antibodies were used for staining at P30 (B). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). (C) Cell death at P18 and P30 was assessed by TUNEL staining (green) of retinas of indicated genotypes. Graphical representation from three different experiments of number of TUNEL-positive (green) cells in the ONL is depicted on the right. Nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars: 20 μm. Number of mice in (A) is indicated as n. *P < 0.001.

Photoreceptor Cell Death in Double-Mutant Mice

We then asked whether improved photoreceptor structure and function is associated with decrease in cell death. To this end, we performed TUNEL staining of retinas of different genotypes. As shown in Figure 5C, we found significantly reduced TUNEL-positive nuclei in the outer nuclear layer in the Cep290rd16: Rkipko/ko mice compared with Cep290rd16 (P < 0.01) at P18. As control, very few TUNEL-positive cells were present in Rkipko/ko mouse retina. Staining with TUNEL at P30 (Fig. 5C) revealed that cell death in the Cep290rd16 mouse retina was almost completed and very low levels of TUNEL-positive nuclei were observed. Nonetheless, cell death continued at P30 in the Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko retina and we observed significantly high number of TUNEL-positive nuclei in the ONL compared with Cep290rd16 (P < 0.001) at P30, but reduced TUNEL-positive nuclei compared with P18. Overall, these results indicate a transient rescue in phenotype and a continued but delayed degeneration of photoreceptors in the double knockout mice.

Discussion

Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA; MIM 204000) is one of the most severe forms of congenital blindness disorders.25,26 Over 13 genes have now been identified to be associated with autosomal recessive LCA cases. Gene therapeutic strategies for LCA have shown promise both in animal models and in patients who develop moderate visual impairment at infancy progressing into total blindness by mid to late adulthood.30–33 Mutations in CEP290 result in relatively early onset severe retinal degeneration and dysfunction in mice and humans. The fast progression of the disease makes it difficult to pinpoint the stage at which therapeutic intermediates can be implemented. Our studies reported here show that retinal degeneration in the Cep290rd16 mouse can be delayed by downregulating the expression of RKIP, potentially making it amenable to other therapeutic paradigms. Such intermediates can be used in combination with other strategies, such as antisense oligonucleotide therapy for CEP290 mutations,34 to improve the outcome of the treatment.

Intracellular levels of other CEP290-interacting proteins such as BBS6 and BBS4 have been shown to positively or negatively affect the phenotype of the rd16 mouse.22,35 However, it should be noted that these proteins are involved in human ciliopathies and that modulating their levels as a therapeutic paradigm can have negative effects. Loss of RKIP, on the other hand, does not seem to perturb development or survival of photoreceptors. Therefore, RKIP and other such proteins are potentially suitable candidates for targeted therapy to delay photoreceptor death. As RKIP is involved in regulating MAP Kinase signaling,36 further studies on the role of these pathways in modulating photoreceptor development and survival should also provide candidate pathway intermediates that can be used in combination with other therapeutic strategies.

Although we observed increased thickness of the ONL at P18, the increase in scotopic A-wave and B-wave responses at P18 did not improve to WT levels. This suggests that although there is increased survival of photoreceptors in the Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko mice, they may not be completely normal and may still possess trafficking defects as well as stress due to severity of the disease in the absence of functional CEP290. Such results further inform about the complexities associated with CEP290-associated retinal degeneration. Our observation of delayed but significant preservation of cone function as detected by photopic B-wave at P30 is probably due to an indirect effect of sustained retinal health because of increase in the surviving rod photoreceptors. In fact, we also detect rod photoreceptors at P30 although their function is considerably reduced in the Cep290rd16:Rkipko/ko mice. However, we cannot rule out a specific effect of loss of RKIP in cones in the Cep290rd16 mouse that results in a delayed improvement in cone function. Previous studies have shown that CEP290 mutations can have differential effects on cones, indicating a distinct role of CEP290, and potentially its interacting proteins, in these cell types.37 Further studies are needed to assess these scenarios in a cell-type specific manner.

The results presented here point to a role of CEP290 in modulating RKIP levels for normal photoreceptor development and survival. It has been shown that RKIP is degraded via the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS).38 Given the involvement of cilia and basal body proteins in regulating the UPS,39,40 it is conceivable that CEP290 targets RKIP to the UPS. Elegant recent studies have shown that proteasomal dysfunction due to overload of proteins being targeted to degradation can be a common underlying mechanism in multiple models of retinal degeneration.41 Therefore, it is possible that reduction in RKIP levels assists in reducing the load on the proteasome and results in a slight improvement in photoreceptor survival. Additional investigations are needed to clearly dissect the role of CEP290 in maintaining the levels of RKIP in the retina.

A transient delay in retinal degeneration in the absence of RKIP in the Cep290rd16 mice indicates involvement of additional pathways that culminate in photoreceptor dysfunction and degeneration. Further studies hold promise of identification of other RKIP-like CEP290-interacting proteins or additional pathways involving CEP290 that can be modulated to retain the ability to improve photoreceptor health in disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gregory Pazour and George Witman (UMASS Medical School), Carlos A. Murga-Zamalloa (University of Michigan), and Rivka A. Rachel (National Eye Institute) for helpful discussions; and Garrett Grahek (University of Michigan) for assistance with ERG; UMASS Cell Biology Confocal Core and Electron Microscopy Core (Award # S10RR027897).

Supported by grants from Foundation Fighting Blindness (HK) and National Eye Institute (EY022372; HK). The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Disclosure: B. Subramanian, None; M. Anand, None; N.W. Khan, None; H. Khanna, None

References

- 1. Doxsey S. Re-evaluating centrosome function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001; 2: 688–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Insinna C, Besharse JC. Intraflagellar transport and the sensory outer segment of vertebrate photoreceptors. Dev Dyn. 2008; 237: 1982–1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mazelova J, Astuto-Gribble L, Inoue H, et al. Ciliary targeting motif VxPx directs assembly of a trafficking module through Arf4. EMBO J. 2009; 28: 183–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nachury MV, Seeley ES, Jin H. Trafficking to the ciliary membrane: how to get across the periciliary diffusion barrier? Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010; 26: 59–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nigg EA, Raff JW. Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell. 2009; 139: 663–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Novarino G, Akizu N, Gleeson JG. Modeling human disease in humans: the ciliopathies. Cell. 2011; 147: 70–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Besharse JC, Baker SA, Luby-Phelps K, Pazour GJ. Photoreceptor intersegmental transport and retinal degeneration: a conserved pathway common to motile and sensory cilia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003; 533: 157–164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu Q, Tan G, Levenkova N, et al. The proteome of the mouse photoreceptor sensory cilium complex. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007; 6: 1299–1317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Murga-Zamalloa C, Swaroop A, Khanna H. Multiprotein complexes of retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR), a ciliary protein mutated in x-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP). Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010; 664: 105–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yildiz O, Khanna H. Ciliary signaling cascades in photoreceptors. Vision Res. 2012; 75: 112–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Besharse JC, Hollyfield JG. Renewal of normal and degenerating photoreceptor outer segments in the Ozark cave salamander. J Exp Zool. 1976; 198: 287–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Besharse JC, Hollyfield JG, Rayborn ME. Photoreceptor outer segments: accelerated membrane renewal in rods after exposure to light. Science. 1977; 196: 536–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deretic D, Schmerl S, Hargrave PA, Arendt A, McDowell JH. Regulation of sorting and post-Golgi trafficking of rhodopsin by its C-terminal sequence QVS(A)PA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998; 95: 10620–10625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li L, Khan N, Hurd T, et al. Ablation of the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa 2 (Rp2) gene in mice results in opsin mislocalization and photoreceptor degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 4503–4511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Young RW. Passage of newly formed protein through the connecting cilium of retina rods in the frog. J Ultrastruct Res. 1968; 23: 462–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anand M, Khanna H. Ciliary transition zone (TZ) proteins RPGR and CEP290: role in photoreceptor cilia and degenerative diseases. Exp Opin Ther Tar. 2012; 16: 541–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim J, Krishnaswami SR, Gleeson JG. CEP290 interacts with the centriolar satellite component PCM-1 and is required for Rab8 localization to the primary cilium. Hum Mol Genet. 2008; 17: 3796–3805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murga-Zamalloa CA, Ghosh AK, Patil SB, et al. Accumulation of the Raf-1 kinase inhibitory protein (Rkip) is associated with Cep290-mediated photoreceptor degeneration in ciliopathies. J Biol Chem. 2011; 286: 28276–28286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tsang WY, Bossard C, Khanna H, et al. CP110 suppresses primary cilia formation through its interaction with CEP290, a protein deficient in human ciliary disease. Dev Cell. 2008; 15: 187–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chang B, Khanna H, Hawes N, et al. In-frame deletion in a novel centrosomal/ciliary protein CEP290/NPHP6 perturbs its interaction with RPGR and results in early-onset retinal degeneration in the rd16 mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2006; 15: 1847–1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Craige B, Tsao CC, Diener DR, et al. CEP290 tethers flagellar transition zone microtubules to the membrane and regulates flagellar protein content. J Cell Biol. 2010; 190: 927–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rachel RA, May-Simera HL, Veleri S, et al. Combining Cep290 and Mkks ciliopathy alleles in mice rescues sensory defects and restores ciliogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2012; 122: 1233–1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. den Hollander AI, Koenekoop RK, Yzer S, et al. Mutations in the CEP290 (NPHP6) gene are a frequent cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2006; 79: 556–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. den Hollander AI, Roepman R, Koenekoop RK, Cremers FP. Leber congenital amaurosis: genes, proteins and disease mechanisms. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008; 27: 391–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Estrada-Cuzcano A, Roepman R, Cremers FP, den Hollander AI, Mans DA. Non-syndromic retinal ciliopathies: translating gene discovery into therapy. Hum Mol Genet. 2012; 21: R111–R124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koenekoop RK. An overview of Leber congenital amaurosis: a model to understand human retinal development. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004; 49: 379–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Badano JL, Mitsuma N, Beales PL, Katsanis N. The ciliopathies: an emerging class of human genetic disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006; 7: 125–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Menotti-Raymond M, David VA, Schaffer AA, et al. Mutation in CEP290 discovered for cat model of human retinal degeneration. J Hered. 2007; 98: 211–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Theroux S, Pereira M, Casten KS, et al. Raf kinase inhibitory protein knockout mice: expression in the brain and olfaction deficit. Brain Res Bull. 2007; 71: 559–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Acland GM, Aguirre GD, Ray J, et al. Gene therapy restores vision in a canine model of childhood blindness. Nat Genet. 2001; 28: 92–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cideciyan AV, Hauswirth WW, Aleman TS, et al. Human RPE65 gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis: persistence of early visual improvements and safety at 1 year. Hum Gene Ther. 2009; 20: 999–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maguire AM, High KA, Auricchio A, et al. Age-dependent effects of RPE65 gene therapy for Leber's congenital amaurosis: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2009; 374: 1597–1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pawlyk BS, Bulgakov OV, Liu X, et al. Replacement gene therapy with a human RPGRIP1 sequence slows photoreceptor degeneration in a murine model of Leber congenital amaurosis. Hum Gene Ther. 2010; 21: 993–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Collin RW, den Hollander AI, van der Velde-Visser SD, Bennicelli J, Bennett J, Cremers FP. Antisense oligonucleotide (AON)-based therapy for Leber Congenital Amaurosis caused by a frequent mutation in CEP290. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2012; 1: e14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang Y, Seo S, Bhattarai S, et al. BBS mutations modify phenotypic expression of CEP290-related ciliopathies. Hum Mol Genet. 2014; 23: 40–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Al-Mulla F, Bitar MS, Taqi Z, Yeung KC. RKIP: much more than Raf kinase inhibitory protein. J Cell Physiol. 2013; 228: 1688–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cideciyan AV, Aleman TS, Jacobson SG, et al. Centrosomal-ciliary gene CEP290/NPHP6 mutations result in blindness with unexpected sparing of photoreceptors and visual brain: implications for therapy of Leber congenital amaurosis. Hum Mutat. 2007; 28: 1074–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Qu Y, Dang S, Hou P. Gene methylation in gastric cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2013; 424: 53–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gerdes JM, Liu Y, Zaghloul NA, et al. Disruption of the basal body compromises proteasomal function and perturbs intracellular Wnt response. Nat Genet. 2007; 39: 1350–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu YP, Tsai IC, Morleo M, et al. Ciliopathy proteins regulate paracrine signaling by modulating proteasomal degradation of mediators. J Clin Invest. 2014; 124: 2059–2070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lobanova ES, Finkelstein S, Skiba NP, Arshavsky VY. Proteasome overload is a common stress factor in multiple forms of inherited retinal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013; 110: 9986–9991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhu X, Brown B, Li A, Mears AJ, Swaroop A, Craft CM. GRK1-dependent phosphorylation of S and M opsins and their binding to cone arrestin during cone phototransduction in the mouse retina. J Neurosci. 2003; 23: 6152–6160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]