Abstract

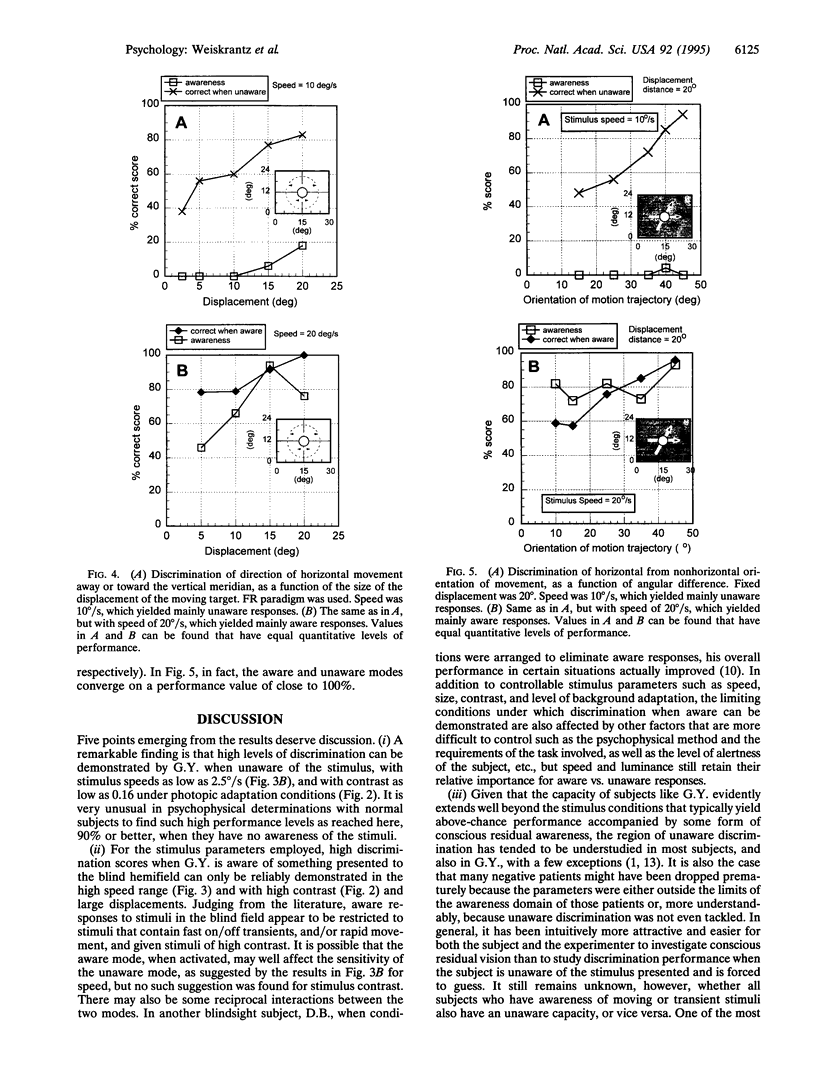

When the visual (striate) cortex (V1) is damaged in human subjects, cortical blindness results in the contralateral visual half field. Nevertheless, under some experimental conditions, subjects demonstrate a capacity to make visual discriminations in the blind hemifield (blindsight), even though they have no phenomenal experience of seeing. This capacity must, therefore, be mediated by parallel projections to other brain areas. It is also the case that some subjects have conscious residual vision in response to fast moving stimuli or sudden changes in light flux level presented to the blind hemifield, characterized by a contentless kind of awareness, a feeling of something happening, albeit not normal seeing. The relationship between these two modes of discrimination has never been studied systematically. We examine, in the same experiment, both the unconscious discrimination and the conscious visual awareness of moving stimuli in a subject with unilateral damage to V1. The results demonstrate an excellent capacity to discriminate motion direction and orientation in the absence of acknowledged perceptual awareness. Discrimination of the stimulus parameters for acknowledged awareness apparently follows a different functional relationship with respect to stimulus speed, displacement, and stimulus contrast. As performance in the two modes can be quantitatively matched, the findings suggest that it should be possible to image brain activity and to identify the active areas involved in the same subject performing the same discrimination task, both with and without conscious awareness, and hence to determine whether any structures contribute uniquely to conscious perception.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barbur J. L., Forsyth P. M., Findlay J. M. Human saccadic eye movements in the absence of the geniculocalcarine projection. Brain. 1988 Feb;111(Pt 1):63–82. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbur J. L., Harlow A. J., Weiskrantz L. Spatial and temporal response properties of residual vision in a case of hemianopia. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1994 Jan 29;343(1304):157–166. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1994.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbur J. L., Ruddock K. H., Waterfield V. A. Human visual responses in the absence of the geniculo-calcarine projection. Brain. 1980 Dec;103(4):905–928. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.4.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbur J. L., Watson J. D., Frackowiak R. S., Zeki S. Conscious visual perception without V1. Brain. 1993 Dec;116(Pt 6):1293–1302. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.6.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blythe I. M., Bromley J. M., Kennard C., Ruddock K. H. Visual discrimination of target displacement remains after damage to the striate cortex in humans. Nature. 1986 Apr 17;320(6063):619–621. doi: 10.1038/320619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blythe I. M., Kennard C., Ruddock K. H. Residual vision in patients with retrogeniculate lesions of the visual pathways. Brain. 1987 Aug;110(Pt 4):887–905. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent P. J., Kennard C., Ruddock K. H. Residual colour vision in a human hemianope: spectral responses and colour discrimination. Proc Biol Sci. 1994 Jun 22;256(1347):219–225. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowey A., Stoerig P. The neurobiology of blindsight. Trends Neurosci. 1991 Apr;14(4):140–145. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libet B., Pearl D. K., Morledge D. E., Gleason C. A., Hosobuchi Y., Barbaro N. M. Control of the transition from sensory detection to sensory awareness in man by the duration of a thalamic stimulus. The cerebral 'time-on' factor. Brain. 1991 Aug;114(Pt 4):1731–1757. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.4.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoerig P., Cowey A. Wavelength discrimination in blindsight. Brain. 1992 Apr;115(Pt 2):425–444. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. D., Myers R., Frackowiak R. S., Hajnal J. V., Woods R. P., Mazziotta J. C., Shipp S., Zeki S. Area V5 of the human brain: evidence from a combined study using positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb Cortex. 1993 Mar-Apr;3(2):79–94. doi: 10.1093/cercor/3.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiskrantz L., Harlow A., Barbur J. L. Factors affecting visual sensitivity in a hemianopic subject. Brain. 1991 Oct;114(Pt 5):2269–2282. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiskrantz L., Warrington E. K., Sanders M. D., Marshall J. Visual capacity in the hemianopic field following a restricted occipital ablation. Brain. 1974 Dec;97(4):709–728. doi: 10.1093/brain/97.1.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]