Abstract

The BAALC/miR-3151 locus on chromosome 8q22 contains both the BAALC gene (for brain and acute leukemia, cytoplasmic) and miR-3151, which is located in intron 1 of BAALC. Older acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients with high expression of both miR-3151 and the BAALC mRNA transcript have a low survival prognosis, and miR-3151 and BAALC expression is associated with poor survival independently of each other. We found that miR-3151 functioned as the oncogenic driver of the BAALC/miR-3151 locus. Increased production of miR-3151 reduced the apoptosis and chemosensitivity of AML cell lines and increased leukemogenesis in mice. Disruption of the TP53-mediated apoptosis pathway occurred in leukemia cells overexpressing miR-3151 and the miR-3151 bound to the 3′ untranslated region of TP53. In contrast, BAALC alone had only limited oncogenic activity. We found that miR-3151 contains its own regulatory element, thus partly uncoupling miR-3151 expression from that of the BAALC transcript. Both genes were bound and stimulated by a complex of the transcription factors SP1 and nuclear factor κB (SP1/NF-κB). Disruption of SP1/NF-κB binding reduced both miR-3151 and BAALC expression. However, expression of only BAALC, but not miR-3151, was stimulated by the transcription factor RUNX1, suggesting a mechanism for the partly discordant expression of miR-3151 and BAALC observed in AML patients. Similar to the AML cells, in melanoma cell lines, overexpression of miR-3151 reduced the abundance of TP53, and knockdown of miR-3151 increased caspase activity, whereas miR-3151 overexpression reduced caspase activity. Thus, this oncogenic miR-3151 may also have a role in solid tumors.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the progress in understanding the biology of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the long-term survival of most patients remains poor (1–3). Numerous gene mutations and the differential expression of leukemia-associated genes have been identified and associated with the prognosis of AML patients (4, 5). Under normal conditions, the BAALC gene is expressed in neural cells and undifferentiated hematopoietic cells, whereas BAALC mRNA is aberrantly expressed in the blast cells (precursors of differentiated blood cells) of some AML and acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients (6–8). In addition, aberrant expression of BAALC has been described in several other malignancies, including malignant melanoma (9), brain tumors (6), and childhood gastrointestinal stromal tumors (10), suggesting the involvement of the BAALC locus in general cancer pathways. In AML patients, overexpression of BAALC is associated with poor prognosis, especially affecting the achievement of complete remission upon chemotherapeutic treatment (11–14). Although BAALC has been extensively studied in the subset of AML patients without chromosomal aberrations in the leukemic blasts [cytogenetically normal (CN) AML], who account for about 50% of all AML patients (4), efforts to demonstrate an independent oncogenic mechanism for BAALC have failed (15).

Several microRNAs (miRs) regulate various cancer-associated pathways (16). Sequences encoding miRs are located throughout the genome, with about one-third residing within introns of the “host” genes (17, 18). However, putative functional interactions between intronic miRs and their host genes have received relatively little attention. The first intron of the BAALC gene contains the miR miR-3151 (19, 20), and this dual product gene is referred to as the BAALC/miR-3151 locus. By analyzing miR-3151 abundance and BAALC transcript abundance in older CN-AML patients, we previously showed that high expression of miR-3151 is independently associated with poor prognosis. Notably, miR-3151 and BAALC transcripts are both detected with concordant transcript abundance in only about two-thirds of all patients. Patients with high expression of both miR-3151 and BAALC had the poorest outcome, and patients with high expression of only one or the other had an intermediate outcome (21). Thus, we hypothesized that miR-3151, not BAALC, may be the oncogenic driver of the miR-3151/BAALC locus, serving either as a crucial partner of its host gene or by functioning independently from its host gene to mediate leukemogenic effects.

Dysfunction or mutation in the TP53 (also known as p53) pathway is implicated in many types of tumorigenesis including AML (21). The TP53 pathway is activated by various types of cellular stress, including DNA damage, and activation of this pathway can lead to either cell cycle arrest or apoptosis (23). Restoration of TP53 expression in leukemic cells lacking p53 reduces cell viability by activation of apoptosis (24).

We now identified TP53 as a direct downstream target of miR-3151. Deregulation of TP53 and its associated apoptosis pathway led to a more aggressive disease phenotype both in vitro and in our xenograft model, thereby suggesting that miR-3151 is the crucial oncogenic product of the miR-3151/BAALC locus. In addition, we characterized an upstream regulator of miR-3151—the transcription factor complex SP1/nuclear factor κB (NF-κB).

RESULTS

miR-3151 deregulates the TP53 pathway

A gene expression profile (GEP) comprising 374 differentially expressed annotated genes is associated with high miR-3151 abundance in 179 CN-AML patients (21). We performed a canonical pathway analysis using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software on this GEP and found that TP53 signaling scored as the top canonical pathway associated with high miR-3151 abundance (Table 1). We identified two putative miR-3151–binding sites in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of TP53, suggesting that TP53 may be a direct target of miR-3151. Therefore, we hypothesized that inhibition of TP53 activity by down-regulation of its expression may be a mechanism by which miR-3151 promotes leukemogenesis.

Table 1. Canonical pathway analysis of the miR-3151–associated gene expression signature.

Listed are the top-ranking entries of the canonical pathway category after pathway analysis (http://www.ingenuity.com) of the miR-3151–associated gene expression signature (21). Ratio represents the number of differentially expressed genes/total genes in the pathway.

| Ingenuity canonical pathways | P | Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| p53 signaling (TP53 signaling) | 8.51 × 10−5 | 9/96, 9.38 × 10−2 |

| Cdc42 signaling | 1.32 × 10−4 | 10/180, 5.56 × 10−2 |

| ERK/MAPK signaling | 2.26 × 10−4 | 12/204, 5.88 × 10−2 |

| Breast cancer regulation by stathmin 1 | 3.9 × 10−4 | 12/210, 5.71 × 10−2 |

| B cell development | 2.02 × 10−3 | 4/37, 1.08 × 10−1 |

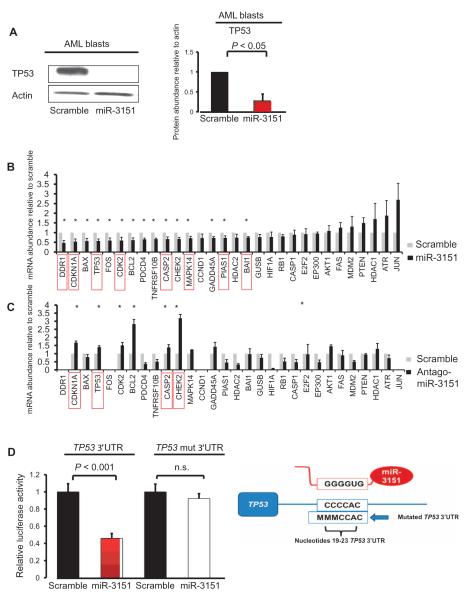

Because the abundance of the BAALC transcript—in particular, the variant containing exons 1, 6, and 8—has been associated with AML, we examined the effect of overexpression of miR-3151, the transcript containing exons 1, 6, and 8 encoded by BAALC, or both in two AML cell lines, KG1 and MV4-11. Overexpression of miR-3151 reduced the abundance of TP53 mRNA and TP53 protein in both of the AML cell lines (Fig. 1, A to C). Although expression of this BAALC transcript (referred to hereinafter as BAALC1,6,8) alone did not significantly alter TP53 expression, overexpression of both miR-3151 and BAALC1,6,8 reduced TP53 expression in KG1 and MV4-11 cells (Fig. 1B). Because KG1 cells harbor a TP53 mutation that prevents the binding of commercially available antibodies, we analyzed the effect of miR-3151 on TP53 at the protein level by Western blotting in MV4-11 cells, which confirmed the decrease in TP53 in response to overexpression of miR-3151 (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. miR-3151 reduces the abundance of the TP53 transcript and protein.

(A) Effect of lentivirally mediated stable expression of miR-3151 or a scramble control on TP53 mRNA abundance in KG1 and MV4-11 cells. Data were normalized to the scramble control value for each cell line (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values based on two-tailed Student’s t test). (B) Effect of lentivirally mediated stable expression of miR-3151, BAALC, or both (miR-3151/BAALC) on TP53 mRNA abundance in KG1 and MV4-11 cells. Data were normalized to the scramble control value for each cell line (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values based on two-tailed Student’s t test). (C) Western blot analysis of TP53 abundance comparing miR-3151–infected MV4-11 cells with scramble control. Left: representative blot; right: quantification of the changes relative to actin as determined by densitometry (mean ± SD, n = 3 blots; P values based on one-tailed Student’s t test).

We measured miR-3151 abundance and BAALC expression in blasts isolated from eight CN-AML patients by quantitative real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) (Table 2) and used these data to divide the patient cells and the cell lines into high and low miR-3151/BAALC expressers (Table 2). Cells from CN-AML patients 1 to 4 exhibited a viability of >75% and were therefore selected for further experiments. First, we infected the primary blasts from these four CN-AML patients with either a lentiviral miR-3151 expression construct or scramble control and monitored the expression of 30 genes associated with the TP53 pathway using qRT-PCR. We confirmed increased abundance of miRNA-3151 in the patient cells (Table 2) and the reduction in TP53 abundance at the protein level in CN-AML patient blasts 1 to 3 (Fig. 2A and fig. S1). A comparison of the miR-3151–overexpressing patient blasts with those expressing the scramble control revealed a significant reduction in the abundance of transcripts for 15 of 30 TP53 pathway–associated genes, and 9 transcripts showed an increase in abundance (Fig. 2B). We focused on the genes with reduced expression in the presence of increased miR-3151 abundance because these could represent direct miR-3151 targets. In silico analysis of the 15 significantly down-regulated genes revealed that, in addition to TP53, seven of the other genes also contain putative miR-3151–binding sites in their 3′UTRs and, therefore, represent potential direct targets of miR-3151 (DDR1, CDKN1A, CDK2, CASP2, MAPK14, PIAS1, and BAI1) (Fig. 2C, red boxes).

Table 2. Cytogenetics and molecular information on AML patients studied.

miR-3151 and BAALC expression was determined in all patients by qRT-PCR before and after forced expression of miR-3151/BAALC. Median expression before forced expression was used to divide the patient cells into high- and low-expressing groups. Primary blasts of AML patients 1, 2, 3, and 4 were used for further in vitro studies. FLT3-ITD, internal tandem duplications in the gene encoding fms-related tyrosine kinase 3, mutated (ITD-positive) versus wild type (ITD-negative); NPM1, gene encoding nucleophosmin; n.a., not applicable; WT, wild type.

| Cells | Cytogenetics | FLT3-ITD | NPM1 |

miR-3151/BAALC expression at diagnosis (high versus low) |

miR-3151/BAALC expression after forced expression (high versus low) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AML patients | |||||

| 1 | Normal | Mutated | WT | Low | High |

| 2 | Normal | Mutated | WT | High | High |

| 3 | Normal | WT | Mutated | High | High |

| 4 | Normal | Mutated | WT | High | High |

| 5 | Normal | WT | Mutated | Low | n.a. |

| 6 | Normal | WT | Mutated | Low | n.a. |

| 7 | Normal | Mutated | Mutated | High | n.a. |

| 8 | Normal | WT | Mutated | Low | n.a. |

| Cell lines | |||||

| KG1a | n.a. | High | n.a. | ||

| MV4-11 | n.a. | Low | High | ||

| KG1 | n.a. | Low | High | ||

Fig. 2. miR-3151 directly targets the 3′UTR of TP53 and regulates TP53 pathway–associated gene expression.

(A) Representative Western blot of TP53 abundance in miR-3151–overexpressing patient cells or those expressing the scramble control. Blot is from AML patient 2 (for representative blots for the other patients, see fig. S1). The bar graph on the right side depicts the changes in protein abundance as determined by densitometry (mean ± SD, n = 3 blots from AML patients 1 to 3; P values based on one-tailed Student’s t test). (B) Primary blasts of AML patients 1 to 4 were stably infected with miR-3151 expression construct or the scramble control, and the mRNA abundance of 30 TP53 pathway members was analyzed by qRT-PCR. The changes in mRNA abundance by overexpression of miR-3151 in the blasts from AML patients 1 to 4 compared to their respective scramble controls were combined, and the graphs show means ± SEM (scramble set to 1; *P < 0.05 as determined by one-tailed Student’s t test). Red boxes indicate the genes with one or more predicted miR-3151–binding sites in their 3′UTR (http://www.microrna.org). (C) KG1a cells were infected with antagomiR-3151 expression construct or the scramble control, and the mRNA abundance of 30 TP53 pathway–associated genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR (n = 3 biological replicates). Four genes (DDR1, FOS, CCND1, and JUN) failed in the qRT-PCR and are not depicted in the bar graphs. The graphs show means ± SEM (scramble set to 1; *P < 0.05 as determined by one-tailed Student’s t test). Red boxes indicate the genes with one or more predicted miR-3151–binding sites in their 3′UTR (http://www.microrna.org). (D) Luciferase assay using the TP53 3′UTR in the presence or absence of miR-3151 in HEK293 cells. Addition of miR-3151 resulted in a 54% decrease in luciferase activity compared to scramble control (transient transfection). This effect was abrogated after mutation of the sequences of the predicted miR-3151–binding site (labeled as TP53 mut 3′UTR; mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). The cartoon on the right side of the graph depicts the alignment of miR-3151 to the TP53 3′UTR (nucleotides 19 to 23) and the mutated nucleotides of the seed sequence. n.s., not significant.

To further validate the altered expression of the TP53 pathway–associated genes by miR-3151, we performed a stable miR-3151 knockdown using a lentiviral single-stranded shRNA hairpin construct (miRZIP, antagomiR-3151) in KG1a cells, which are high miR-3151/BAALC expressers (Table 2). The effects of antagomiR-3151 on the mRNA abundance of TP53-associated genes were then analyzed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 2C). Knockdown of miR-3151 significantly increased the abundance of transcripts for seven TP53 pathway–associated genes, including TP53, and six of these seven genes were also down-regulated in cells overexpressing miR-3151 (Fig. 2, B and C): CHEK2, BCL2, CDKN1A, CDK2, TP53, and MAPK14.

Because the 3′UTR of TP53 is predicted to contain two consensus miR-3151–binding sites (nucleotides 19 to 23 and nucleotides 1108 to 1114), TP53 may be a direct target of miR-3151. To confirm the ability of miR-3151 to bind these sequences and regulate transcript stability and protein synthesis, we cloned the 3′UTR with the sequence containing the proximal of the two predicted miR-3151–binding sites into a luciferase reporter vector and expressed both miR-3151 and the reporter gene with the consensus miR-3151–binding site or a binding site mutant in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells. Compared with expression of a scramble control, increased abundance of miR-3151 reduced the luciferase activity (Fig. 2D), and this effect was abrogated after mutation of the seed sequence of the predicted miR-3151–binding site (Fig. 2D), suggesting that TP53 is a direct target of miR-3151.

Increased miR-3151 abundance increases the growth of AML cell lines, an effect that is enhanced by co-infection with its host gene BAALC

Because higher amounts of miR-3151 are associated with a shorter disease-free period and decreased overall survival in CN-AML patients (21) and because our data suggested that TP53 is a direct target of miR-3151, we tested whether overexpression of miR-3151 or miR-3151 and BAALC in combination would affect the proliferation of leukemia cells, measured as the number of cells in culture over a period.

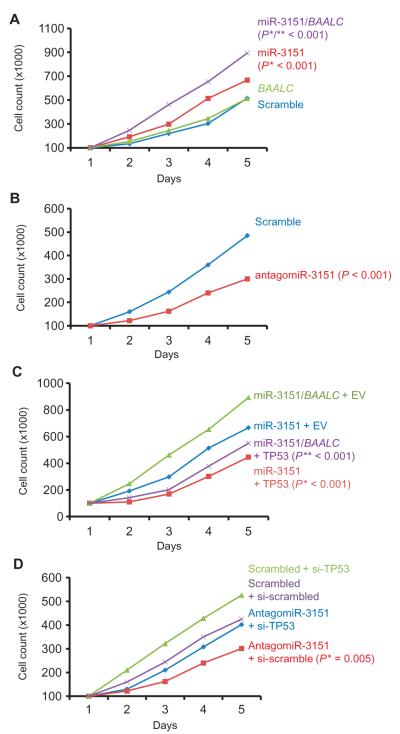

Using MV4-11 cells (low miR-3151/BAALC expressers) for overexpression and KG1a cells (high miR-3151/BAALC expressers) for knockdown, we showed that increasing the abundance of miR-3151 increased cell numbers (Fig. 3A), whereas knockdown of miR-3151 with antagomiR-3151 inhibited cell growth (Fig. 3B). Although MV4-11 cell numbers were unaffected by overexpression of BAALC, MV4-11 cells overexpressing both miR-3151 and BAALC had the fastest growth rates (Fig. 3A), which is consistent with the data indicating that patients with high expression of both gene products have the worst prognosis (21).

Fig. 3. Changing the abundance of miR-3151 alters growth in part through TP53.

(A) MV4-11 cells were stably infected with miR-3151, BAALC, scramble, or both miR-3151 and BAALC expression constructs (n = 3 biological replicates). Successfully infected cells (as determined by GFP positivity) were counted in duplicate for five consecutive days. (* indicates comparison with scramble; ** indicates comparison with miR-3151). (B) KG1a cells were stably infected with antagomiR-3151 or scramble expression constructs (n = 3 biological replicates). Cells were counted in duplicate for five consecutive days. (C) MV4-11 cells stably expressing miR-3151 or both miR-3151 and BAALC were transiently transfected with either vector containing TP53 or empty vector (EV). Starting at 24 hours after transfection, cells were counted in duplicate for five consecutive days. (* indicates comparison with miR-3151 + EV; ** indicates comparison with miR-3151/BAALC + EV). (D) TP53 was knocked down with siRNA in KG1a cells stably expressing antagomiR-3151 or scramble control constructs. Data in all panels are plotted as median cell counts on each day. All P values were determined by two-tailed Student’s t test. Error bars are omitted to improve clarity.

Because TP53 appears to be a direct target of miR-3151, we tested whether altering the abundance of TP53 would influence the effects of miR-3151 on the leukemia cell lines. Overexpression of TP53 in MV4-11 cells stably expressing miR-3151 reduced cell numbers (Fig. 3C), whereas knockdown of TP53 partially rescued the decrease in cell numbers caused by the antagomiR-3151 in KG1a cells [Fig. 3, B and D; comparison of cell growth of antagomiR-3151 versus antagomiR-3151 + TP53 small interfering RNA (siRNA): P = 0.001].

miR-3151 alone and in combination with BAALC inhibits apoptosis of AML cell lines

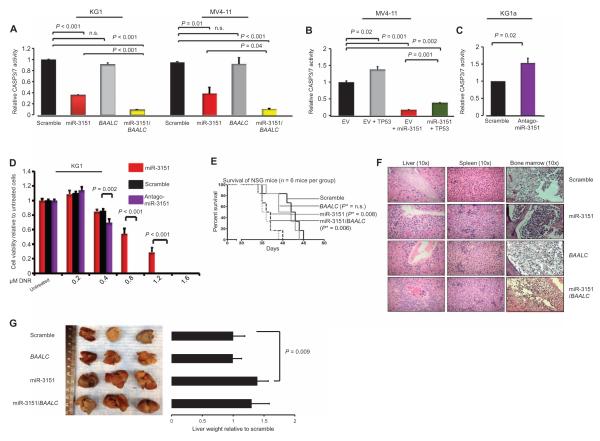

The apparent increase in growth can result from an increase in the rate of cell division or from a decrease in apoptosis or a combination of the two. To determine whether overexpression of miR-3151 resulted in a decrease in apoptosis, which is one of the responses to activation of the TP53 pathway, we performed chemiluminescence assays to assess the activities of caspases 3 and 7 (CASP3/7). Because we showed that miR-3151 decreased the abundance of TP53 and these two caspases are effectors of the TP53-mediated apoptosis cascade, we predicted that overexpression of miR-3151 would decrease the activity of these enzymes, leading to reduced apoptosis.

Analysis of the CASP3/7 activities in KG1 and MV4-11 cells showed that cells overexpressing miR-3151 or miR-3151 and BAALC1,6,8, but not the ones solely overexpressing BAALC1,6,8, had a decrease in caspase activity. The combination of miR-3151 and BAALC1,6,8 produced the largest inhibitory effect (Fig. 4A). MV4-11 cells simultaneously overexpressing miR-3151 and TP53 exhibited an intermediate amount of caspase activity that was less than that in the TP53 only–expressing cells and more than that in the miR-3151–expressing cells (Fig. 4B), suggesting that increasing TP53 abundance may partially overcome the inhibition of apoptosis mediated by miR-3151. Knockdown of miR-3151 in the high miR-3151/BAALC–expressing KG1a cells increased caspase activity (Fig. 4C). We also performed Western blotting to quantify the amounts of cleaved and uncleaved CASP3, with an increase in cleaved CASP3 indicating active apoptosis. Consistent with the caspase activity assays, overexpression of miR-3151 reduced the amount of cleaved CASP3 in MV4-11 cells, and knockdown of miR-3151 in KG1a cells increased CASP3 cleavage (fig. S2).

Fig. 4. miR-3151 and miR-3151/BAALC inhibit apoptosis of AML cell lines, and increased miR-3151 results in increased leukemogenesis in vivo.

(A) Chemiluminescence assays of CASP3/7 in KG1 and MV4-11 cells after stable infection with miR-3151, BAALC, or scramble control (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). (B) Amount of CASP3/7 activity in MV4-11 cells stably expressing miR-3151 and transiently expressing TP53 or an empty vector (EV) control (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). (C) Caspase activity in KG1a cells in response to stable infection with antagomiR-3151 (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). (D) Cell viability of KG1a cells stably expressing miR-3151, antagomiR-3151, or scramble as determined by MTS assays 72 hours after exposure to the indicated doses of daunorubicin (DNR; n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). (E) Survival of NSG mice after injection of MV4-11 cells stably overexpressing miR-3151, BAALC, miR-3151/BAALC, or scramble control (n = 6 mice per group). Statistical significance in survival was determined by log-rank test. *P value depicts comparison with scramble. (F) Representative pictures of hematoxylin and eosin staining of livers, spleens, and bone marrows of the mice. All organs showed infiltration with leukemic blasts. The hepatic blast infiltration was especially pronounced in the miR-3151 and miR-3151/BAALC mice and was predominantly seen around the blood vessels. (G) Representative images of the macroscopic appearance of livers collected postmortem from NSG mice. The bar graphs show the corresponding liver weights (in grams, n = 6 organs) relative to scramble control. P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test.

To test whether the apoptosis-inhibiting effect of miR-3151 increased resistance to the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapeutic agents, we exposed KG1a cells stably expressing either miR-3151 or antagomiR-3151 to increasing doses of the intercalating chemotherapeutic agent daunorubicin, which is a standard therapeutic agents used for the treatment of AML. Overexpression of miR-3151 decreased the sensitivity of the cells to daunorubicin, whereas the antagomiR-3151 reduced cell viability in response to lower concentrations of daunorubicin (Fig. 4D).

Overexpression of miR-3151 alone and in combination with BAALC causes increased leukemogenesis in vivo

To test whether overexpression of miR-3151 or BAALC1,6,8 or the combination of the two would increase leukemia cell growth and produce a more aggressive disease phenotype in vivo, we stably overexpressed miR-3151, BAALC, or the combination in murine-adapted MV4-11 cells and then injected the cells into immunodeficient mice [nonobese diabetic (NOD) severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) γ knockout (NSG)]. Depending on the number of cells injected, these mice develop an aggressive leukemia 3 to 6 weeks after injection and die within 2 to 5 days after development of initial disease symptoms (25). We verified the engraftment of the MV4-11 cells by monitoring the presence of CD45+ cells by flow cytometry in the peripheral blood of a mouse in each group without external signs of disease (fig. S3).

Mice receiving cells overexpressing miR-3151 alone or miR-3151 and BAALC had the shortest survival, whereas the median survival of the mice receiving BAALC-overexpressing cells did not differ from the survival of mice receiving cells expressing scramble controls (Fig. 4E).

We collected the organs from every mouse postmortem and analyzed them macroscopically and histopathologically. Microscopic inspection of the bone marrows, spleens, and livers revealed infiltration of blast cells, validating leukemia development in all mice, including those receiving scramble control cells (Fig. 4F). The mice injected with miR-3151–overexpressing cells had more severe hepatomegaly than the mice injected with cells expressing the scramble control (Fig. 4G). The observed hepatomegaly in the group receiving miR-3151–overexpressing cells was consistent with the increased leukemic blast infiltration present in the histopathological analysis of the livers in these mice (Fig. 4F).

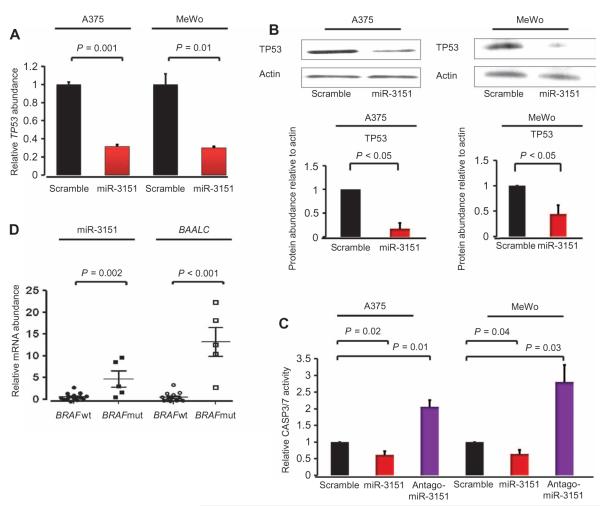

miR-3151 decreases TP53 transcripts and protein and reduces apoptosis of melanoma cell lines

Because miR-3151 was initially identified by deep sequencing of melanoma samples (19), we hypothesized that the abundance of miR-3151 may also be important in melanoma. We analyzed the effect of overexpression or knockdown of miR-3151 in two melanoma cell lines, A375 cells (BRAFV600E, miR-3151 present in moderate abundance) and MeWo cells (BRAF wild type, miR-3151 less abundant than in the A375 cells). We infected A375 cells and MeWo cells with miR-3151, antagomiR-3151, or scramble expression constructs. In both cell lines, overexpression of miR-3151 resulted in a decrease in the abundance of TP53 transcript (Fig. 5A) and protein (Fig. 5B) compared to cells infected with a scramble control. We also measured the effect of changing miR-3151 abundance on CASP3/7 activity as an indication of apoptosis. Similar to our observations with the AML cell lines, knockdown of miR-3151 significantly increased caspase activity, whereas increasing miR-3151 abundance reduced caspase activity in the melanoma cell lines (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. Effect of miR-3151 on malignant melanoma cell lines.

(A) Effect of overexpression of miR-3151 on TP53 transcript abundance (stable infection; mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). (B) Western blot of TP53 abundance in A375 and MeWo cells stably expressing miR-3151 or the scramble control. The bar graphs depict the change in protein abundance as determined by densitometry (n = 3 blots; P values were determined by one-tailed Student’s t test). (C) CASP3/7 chemiluminescence assays of A375 and MeWo cells after stable infection with scramble control, miR-3151, or antagomiR-3151 (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). (D) Relative abundance of miR-3151 and BAALC in malignant melanoma patients (n = 19) according to their BRAF mutation status. Five patients had the BRAF mutation (mut) and 19 patients had wild-type BRAF (wt). Abundance of miR-3151 or BAALC transcripts in the wild-type patients was set to 1 (mean ± SEM; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test).

BAALC has been reported as the most up-regulated gene of BRAF-mutated melanoma cell lines compared to cell lines that are wild type for BRAF (9). To validate the association of BRAF mutations with high BAALC expression and to test whether the same association occurred with miR-3151 abundance, we screened 19 malignant melanoma samples for the presence of the BRAFV600E mutation and assessed the abundance of BAALC transcripts and miR-3151. The BRAF mutation was detected in 5 of 19 patients. When compared with melanoma patients with wild-type BRAF, BAALC transcripts and miR-3151 were more abundant in patients with mutated BRAF (Fig. 5D). These data suggest that BRAF mutation may contribute to the aberrant expression of the BAALC/miR-3151 locus.

miR-3151 contains an independent regulatory element that binds an SP1/NF-κB transactivation complex

Previous association analyses revealed that about one-third of CN-AML patients exhibited a discordant expression status for miR-3151 and BAALC (21). Thus, we hypothesized that miR-3151 contained a regulatory element that enables BAALC-independent expression of miR-3151.

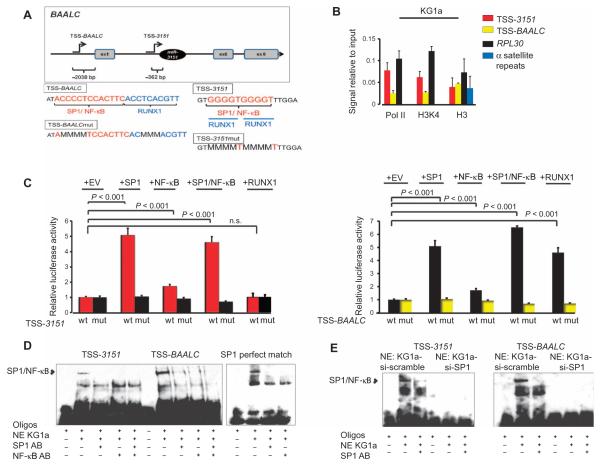

Using genomic prediction tools, we identified a putative transcription start site (TSS-3151) for miR-3151 located 362 base pairs (bp) upstream of the stem loop of miR-3151 and another transcription start site located 2038 bp upstream of the ATG of BAALC (TSS-BAALC) (Fig. 6A). To obtain evidence that the predicted TSSs had regulatory potential, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays for RNA polymerase II (Pol II), histone H3 methylated Lys4 (H3K4), and total histone H3 and tested for their enrichment on TSS-3151 and TSS-BAALC using DNA isolated from high miR-3151/BAALC–expressing KG1a cells. Although total histone H3 does not distinguish between activating and repressing histone modifications, H3K4 is a modification associated with transcriptional activation. The gene encoding ribosomal protein L3 (RPL30) served as a positive control for an actively transcribed gene and as such should show H3K4 and Pol II enrichment. Alpha satellite repeats served as a negative control and should not be enriched for H3K4 and Pol II. In these cells, both TSS-3151 and TSS-BAALC showed an enrichment of both the active histone mark H3K4 and Pol II, thereby indicating transcriptional activity. TSS-3151 showed stronger enrichment for Pol II and H3K4 than did the TSS-BAALC (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6. Upstream regulation of miR-3151 and BAALC.

(A) Top: Predicted transcription start sites for miR-3151 and BAALC, located 362 bp upstream of the stem loop of miR-3151 (TSS-3151) and 2038 bp upstream of the ATG of BAALC (TSS-BAALC), respectively (illustration not drawn to scale). The exons present in the most commonly detected transcript are shown. Bottom: Enlargement of the TSS-BAALC and TSS-3151 regions showing the transcription factor binding sites and the mutated binding sequences. (B) ChIP assays for Pol II, H3K4, and total histone H3 (H3) in KG1a cells. The values of the negative immunoglobulin G (IgG) control did not reach the cycle threshold for any of the primers used and are not depicted in the graph. The amount of immunoprecipitated DNA in each sample is represented as signal relative to the amount of input (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates). (C) Luciferase assays of TSS-3151 or TSS-BAALC with cotransfection of SP1, NF-κB (p65), both SP1 and NF-κB (p65), or RUNX1 in HEK293 cells. A luciferase construct of TSS-3151 or TSS-BAALC with mutated transcription factor binding sites was included as a negative control (mut) (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). (D) EMSA of TSS-3151, TSS-BAALC, or an SP1 exact match consensus sequence (SPI perfect match). Addition of nuclear extract (NE) from KG1a cells created the expected shift of SP1/NF-κB, which could be abrogated by the addition of antibodies (AB) specific for SP1 or NF-κB. (E) EMSA of TSS-3151 and TSS-BAALC using nuclear extracts from KG1a cells after SP1 knockdown. EMSA data are representative of two independent experiments.

We used bioinformatics prediction software to identify putative transcription factor binding sites in the regions of TSS-3151 and TSS-BAALC. SP1 and RUNX1 were among the highest-scoring transcription factors, with NF-κB scoring lower (table S1). Because SP1 can function in transactivating complex with the p65 subunit of NF-κB (26), we created luciferase reporter constructs for TSS-3151 and TSS-BAALC and cotransfected these expression constructs for SP1, NF-κB (p65), both SP1 and NF-κB (p65), or RUNX1 into HEK293 cells. Cotransfection of SP1, the combination of SP1 and NF-κB (p65), and, to a lesser extent, NF-κB (p65) alone increased luciferase activity for TSS-3151 and TSS-BAALC (Fig. 6C). However, only cotransfection of RUNX1 with TSS-BAALC, not with TSS-3151, stimulated the reporter gene activity (Fig. 6C). To verify that the reporter gene activity depended on the predicted transcription factor binding sites, we created a total of eight point mutations in the binding sites for SP1 and RUNX1 (overlapping sites) and found that none of the transcription factors stimulated reporter gene activity under these conditions (Fig. 6C).

We confirmed the binding of the SP1 and NF-κB complex to TSS-3151 and TSS-BAALC by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) using nuclear extracts from KG1a cells and sequences representing the two TSSs and an SP1 perfect match consensus binding site (Fig. 6D). SP1 and NF-κB (p65) bound to both TSS-3151 and TSS-BAALC, and the addition of SP1 or NF-κB antibodies eliminated the binding (Fig. 6D). In contrast, EMSAs performed with nuclear extracts harvested from KG1a cells in which SP1 was knocked down exhibited no binding to TSS-3151 or TSS-BAALC (Fig. 6E). These data indicate that SP1 and NF-κB (p65) bind as a complex to these two TSSs.

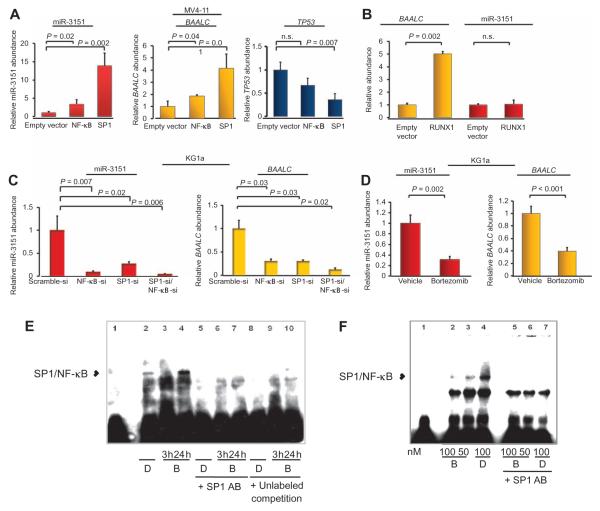

SP1 and NF-κB overexpression increases both miR-3151 and BAALC expression, and RUNX1 increases BAALC expression

To investigate if the transcription factors that bound the TSS would direct the expression of these transcripts in cells, we overexpressed each of the three transcription factors in low-expressing MV4-11 cells. Overexpression of SP1 significantly increased the abundance of miR-3151 and expression of BAALC, with a greater effect on miR-3151 (Fig. 7A). Overexpression of NF-κB had a smaller but still significant effect on miR-3151 and BAALC transcript abundance (Fig. 7A). Consistent with the previous experiment, SP1, but not NF-κB (p65), overexpression decreased the abundance of TP53 transcripts (Fig. 7A). As expected from the luciferase assays with TSS-3151 and TSS-BAALC, overexpression of RUNX1 stimulated an increase in BAALC, but not miR-3151, expression (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7. Bortezomib lowers miR-3151 and BAALC expression.

(A) Effect of SP1 and NF-κB overexpression in MV4-11 cells on the abundance of mature miR-3151 (left), BAALC1,6,8 mRNA (middle), and TP53 mRNA (right). Data are normalized to the abundance in the empty vector–infected cells (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). (B) Effect of overexpression of RUNX1 in MV4-11 cells on the abundance of miR-3151 and BAALC mRNA (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). (C) Effect of knocking down SP1, NF-κB, or both in KG1a cells on the abundance of miR-3151 and BAALC mRNA (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). (D) KG1a cells were exposed to 100 nM bortezomib for 3 hours. The abundance of the indicated RNAs was measured by qRT-PCR and normalized to the amount in the vehicle (DMSO)–treated samples (mean ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates; P values were determined using two-tailed Student’s t test). (E) EMSA of TSS-3151 with nuclear extracts from DMSO (D)–or bortezomib (B)–treated KG1a cells. Nuclear extracts were prepared either 3 or 24 hours after DMSO or bortezomib addition in the presence or absence of 1.2 μg of SP1 antibody or unlabeled TSS-3151 in an amount equal to that of the biotin-labeled TSS-3151. (F) EMSA of TSS-BAALC. The experiment was performed with nuclear extracts (NE) of KG1a cells exposed to DMSO (D) and either 50 or 100 nM bortezomib (B) in the presence or absence of 1.2 μg of SPI antibody. Nuclear extracts were prepared 3 hours after the addition of DMSO or bortezomib. Data in (E) and (F) are representative of two independent experiments.

To investigate the effects of knocking down these transcription factors, we used the high miR-3151/BAALC–expressing KG1a cells. Knockdown of SP1 or NF-κB or both decreased miR-3151 abundance and BAALC expression (Fig. 7C). These results, along with those from the TSS luciferase assays (Fig. 6C), suggested that the SP1/NF-κB transactivating complex is involved in the regulation of miR-3151 and BAALC expression, and that RUNX1 may fine-tune BAALC expression, which may explain the partly discordant expresser status of miR-3151 and BAALC observed in AML patients (21).

miR-3151 abundance and BAALC expression can be reduced by pharmacologic inhibition of SP1/NF-κB binding

The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib abrogates SP1/NF-κB binding to its consensus binding sites (26, 27). Therefore, we exposed high miR-3151/BAALC–expressing KG1a cells to either 100 nM bortezomib or vehicle [dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] and monitored BAALC transcript and miR-3151 abundance by qRT-PCR. The bortezomib concentration used is in accordance with previous experiments and does not exceed clinically relevant doses (26, 27). Bortezomib decreased the abundance of both miR-3151 and the BAALC transcript (Fig. 7D). To confirm that the decrease in their abundance was caused by the disruption of SP1/NF-κB binding to the gene promoters, we performed EMSA with TSS-3151 and TSS-BAALC using nuclear extracts harvested from KG1a cells exposed to bortezomib. We observed reversible inhibition of SP1/NF-κB binding to TSS-3151 (Fig. 7E). When assayed with nuclear extracts prepared from cells 3 hours after bortezomib addition, the shift produced by SP1/NF-κB binding was lost, but when assayed with nuclear extracts prepared from cells 24 hours after exposure, the shift was detectable. An SP1/NF-κB–induced shift was also blocked by the presence of an SP1 antibody or excess unlabeled TSS-3151. Bortezomib also inhibited the binding of SP1/NF-κB to TSS-BAALC (Fig. 7F). These data support the hypothesis that the expression of both miR-3151 and BAALC is activated by the SP1/NF-κB complex and that this activation may be inhibited by pharmacologic inhibition of SP1/NF-κB binding to the promoter sequences (for example, by treatment with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib).

DISCUSSION

Many genes encode both protein products and miRs; however, the regulation and function of these encoded products tend to be studied independently. We set out to determine to what extent the intronic miR-3151 explains the association of the locus and of its host gene, BAALC, with poor survival of AML patients (11–14, 21). We demonstrated that this intronic miR inhibited apoptosis, leading to more rapid cell proliferation in vitro in AML cell lines and leukemogenesis in vivo in mice. Furthermore, BAALC alone showed little functional consequences, but its addition increased the miR-3151 effects; this suggests that the function of miR-3151 may be further enhanced by its host gene through a mechanism that has yet to be characterized.

Previously, we characterized a unique GEP associated with high miR-3151 abundance in 179 CN-AML patients (21). Further analysis of the data identified the TP53 pathway as the one most significantly associated with high miR-3151 abundance. The 3′UTR of TP53 has putative miR-3151–binding sites, and we validated this sequence of TP53 as an miR-3151 target in vitro. Furthermore, we present evidence that the basis of the leukemogenic effect of high miR-3151 abundance may lie in the down-regulation of TP53 abundance, which deregulates the TP53-associated apoptosis cascade. In addition to TP53 itself, we provide evidence that miR-3151 also affects other genes in the TP53 pathway. For example, CDKN1A was one of the most affected by changing miR-3151 abundance. Because CDKN1A also harbors a predicted miR-3151–binding site, CDKN1A is worth investigating as a potentially important direct miR-3151 target in the TP53 pathway.

Whereas increasing only miR-3151 abundance increased leukemogenesis in the MV4-11 NSG mouse model, overexpression of BAALC alone, which also did not affect cell growth and apoptosis in vitro, did not affect mouse survival compared to scramble control.

Disruption of TP53 and proteins associated with its regulation or downstream signaling is a critical event in many solid tumors (22, 24). We validated TP53 as a target of miR-3151 in malignant melanoma cells and found that altering miR-3151 abundance affected the apoptosis cascade. In addition, we determined the BRAF mutation status in a set of malignant melanoma patients who were also analyzed for miR-3151 abundance and BAALC expression. Consistent with a previous report describing high BAALC expression in BRAF-mutated melanoma (9), we found that miR-3151 abundance and BAALC transcripts were increased in BRAF-mutated versus BRAF–wild type melanoma samples. Thus, deregulation of miR-3151 may be important for other human malignancies in addition to AML.

Whereas intergenic miRs are always regulated by their own promoters, intronic miRs can be either regulated with their host gene or regulated independently of their host gene (28, 29). We analyzed the upstream regulatory machinery of the miR-3151/BAALC locus and identified the TSS for each miR-3151 and BAALC, suggesting that the expression of the two genes can be independently regulated. ChIP experiments showed a recruitment of Pol II to the predicted TSS of miR-3151, which has been described as a key feature of intronic miRs with independent regulatory elements (28). In vitro experiments indicated that both genes were stimulated by an SP1/NF-κB transactivating complex, and BAALC expression was additionally stimulated by the transcription factor RUNX1, which may explain the partly discordant expresser status of miR-3151 and BAALC in patients. The identification of RUNX1 as a regulator of BAALC expression agrees with the finding that BAALC expression is associated with the presence of rs62527607[T], a heritable polymorphism in the BAALC promoter region, which creates a binding site for RUNX1 (30). The characterization of the distinct upstream regulatory mechanisms highlights the necessity to carefully analyze potential regulators of intronic miRs that are independent of the host gene.

The SP1/NF-κB transactivating complex stimulates the expression of the genes encoding the tyrosine kinases KIT (26) and FLT3 in AML (27), which, when aberrantly activated, are both associated with poor prognosis of AML patients. Our finding that both miR-3151 and BAALC were regulated by this complex and that pharmacologic inhibition of this SP1/NF-κB–mediated binding reduced miR-3151 abundance and BAALC expression provides additional support for SP1/NF-κB and its regulators as putative therapeutic targets in AML. Further studies to explore the importance of the SP1/NF-κB–miR-3151–TP53 axis and its functional relationship with inhibitors such as bortezomib may be a promising approach toward more personalized treatment options for some AML patients.

In summary, we describe a functional basis for the association of the miR-3151/BAALC locus with poor outcome in AML. Increase dabundance of miR-3151 leads to down-regulation of the TP53 pathway, one of the most important pathways associated with cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue culture experiments and primary patient samples

For studying miR-3151 and BAALC in the context of AML, KG1, KG1a, and MV4-11 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco). Primary AML blasts from leukapheresis samples collected from eight patients with de novo disease were obtained from the Ohio State University (OSU) Leukemia Tissue Bank (Table 2). Patient cells were cultured in StemSpan medium (Stemcell Technologies) without additional supplements. All patients provided written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki to store and use their tissue for discovery studies according to the OSU institutional guidelines under protocols approved by the OSU Institutional Review Board.

For studying miR-3151 and BAALC in malignant melanoma, total RNA samples from 19 malignant melanoma tumors were obtained from Asterand. For in vitro studies, A375 and MeWo cell lines were provided by the laboratory of W.E.C.

For performance of luciferase assays, HEK293 cells, obtained from ATCC, were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% FBS, l-glutamine (200 mM), and antibiotic-antimycotic agent (all from Life Technologies Corporation/Gibco) and grown at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Overexpression of miR-3151 or BAALC and miR-3151 knockdown

For stable expression, the stem loop of miR-3151 with 200-bp flanking sequence and the open reading frame of the main transcript of BAALC (containing exons 1, 6, and 8) were cloned into HIV-based lentiviral dual promoter vectors (pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-copGFP+Puro cDNA and pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro; System Biosciences). All primer sequences can be found in Table 2. For targeted knockdown of miR-3151, a custom-made antagomiR-3151 was purchased from System Biosciences. As a control, lentiviral scramble control miR was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions (miRZiP000, System Biosciences). Lentiviral construct (4500 μg) was transfected into 293TN cells using 45 μg of pPACKH1 and 55 μl of PureFection (System Biosciences). After 48 and 72 hours, the supernatant containing the pseudoviral particles was collected, and the virus was precipitated overnight at 4°C using 5 ml of PEG-IT virus precipitation solution (System Biosciences). Phosphate-buffered saline (200 μl) and 25 μM Hepes buffer were used for resuspension of the pelleted virus. Cells (200,000/ml) were infected in triplicate with 20 IU of virus, using 5 μl of Transdux infection reagent (System Biosciences). Ten days later, successfully infected cells were selected with puromycin for five subsequent days (KG1 and MV4-11 cells: 2 μg/ml; KG1a cells: 2.5 μg/ml).

For simultaneous overexpression of both miR-3151 and BAALC, puromycin-selected miR-3151–overexpressing cells were infected with pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-copGFP+Puro pseudoviral particles expressing both BAALC1,6,8 and green fluorescent protein (GFP). GFP-positive cells were then selected using the FACSAria III cell sorter.

For infection of primary patient blasts, 600,000 cells/ml were infected in triplicate with 20 IU of virus, using 5 μl of Transdux infection reagent (System Biosciences). Infection efficiency was >80% (based on flow cytometric determination of GFP positivity). RNA was harvested after 48 and 72 hours without further selection procedures.

cDNA synthesis and miR-3151 and BAALC mRNA analyses

To check for successful overexpression of miR-3151 and BAALC and to analyze the effect of forced miR-3151 expression on the predicted target genes, RNA from 1 million cells was harvested on day 14 after infection and reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies Corporation/Applied Biosystems) or the SuperScript III First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Life Technologies Corporation/Invitrogen). Both kits were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Simultaneously, protein (from 4 million cells) was harvested and used for Western blotting. miR-3151 abundance and BAALC and target gene mRNA abundances were determined by qRT-PCR as previously described (21).

Luciferase assays for the miR-3151–mediated regulation of TP53

To assess the inhibitory potential of miR-3151 on TP53, 100 bp of the TP53 3′UTR containing one of the predicted miR-3151–binding sites was cloned 3′ of the luciferase gene into a luciferase reporter vector (pGL4.24; Promega) using the Eco RI restriction site. Mutation of the predicted binding site was accomplished using bidirectional mutation primers, exchanging 3 nucleotides (nucleotides 18 to 20 of the TP53 3′UTR) of the respective predicted miR-3151–binding sequences. Primer sequences and the corresponding annealing temperatures are listed in table S3. HEK293 cells were transfected in triplicate with 250 ng of reporter construct and 100 ng of control construct (Renilla, pGL4.74; Promega) using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Life Technologies Corporation/Invitrogen). Cells were cotransfected with 10 pmol of either miR-3151 (Pre-miR miRNA Precursor, Life Technologies Corporation/Ambion) or scramble control miR (Negative Control Pre-miR #1, Life Technologies Corporation/Ambion). Transfected cells were incubated for 12 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Opti-MEM II medium containing the Lipofectamine and plasmid combination. Protein lysates were assessed for firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities according to the recommendations detailed in the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Relative expression was normalized to the activity of cotransfected Renilla luciferase.

Luciferase assays of the miR-3151 and BAALC promoter analysis

Luciferase reporter constructs (~50 bp of genomic sequence) containing the predicted TSS for miR-3151 and BAALC were cloned into the multiple cloning site of the promoterless luciferase reporter vector (pGL4.11, Promega) using the Kpn I and Sac I restriction sites. The predicted binding sequences of the respective transcription factors were mutated using bidirectional mutation primers (all primer sequences used for cloning and mutation introduction are listed in table S3). Expression constructs for the potentially activating transcription factors SP1 and RUNX1 were constructed by cloning the respective open reading frames into the CMV-driven expression vector pIRES2-EGFP (Clontech). The primer sequences for the cDNA-based cloning PCR are listed in table S2. HEK293 cells were transfected in triplicate with 250 ng of luciferase reporter construct and 100 ng of control construct (pGL4.74, Promega) and cotransfected with 50 ng of the different expression constructs or empty pIRES2-EGFP vector control. Transfected cells were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Opti-MEM II medium containing the Lipofectamine and plasmid combination. Protein lysates were assessed for firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase activities according to the recommendations detailed in the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Relative expression was normalized to the activity of cotransfected Renilla luciferase.

Transient overexpression or knockdown of SP1, NF-κB, or RUNX1

For transient overexpression, 3 μg of the overexpression constructs of SP1 and RUNX1 (all cloned in pIRES2-EGFP vector, Clontech) or the p65 subunit of NF-κB (cloned as pCMV-p65) was transfected in triplicate into 3 million MV4-11 and KG1 cells by electroporation (Amaxa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For knockdown of the transcription factors, the following siRNAs were used: SignalSilence NF-κB p65 siRNA I (#6261S, Cell Signaling) and ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool human SP1 (#L-026959-00, Thermo Scientific Dharmacon) (see fig. S4 for confirmation of effective knockdown).

TP53 overexpression and knockdown for cell growth analysis

The open reading frame of TP53 was cloned into the CMV-driven expression vector pIRES2-EGFP (Clontech). The primer sequences for the cDNA-based cloning PCR are listed in table S2. KG1 and MV4-11 cells stably overexpressing miR-3151, BAALC, miR-3151/BAALC, or scramble control were transfected with either 1 μg of TP53 expression construct or empty vector control using PureFection transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (System Biosciences). KG1a cells stably expressing antagomiR-3151 or scramble control were transfected with an siRNA pool against TP53 (sc-29435) (see fig. S4 for confirmation of effective knockdown) or siRNA scramble control (sc-37007) using PureFection transfection reagent. After 12 hours, 100,000 cells per assay were used for growth curve measurements. Cells were counted for five consecutive days using bromophenol blue staining for detection with a hemocytometer.

Leukemogenesis in NSG knockout mice

Ten-week-old male NOD/SCID mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were intravenously injected through the tail vein with 1.5 × 105 murine-adapted MV4-11 cells. Engraftment was validated by flow cytometric determination of CD45 in mice without external signs of disease 37 days after cell injection. Organ samples were harvested from all mice and processed for RNA and microscopy. These studies were performed in accordance with the OSU institutional guidelines for animal care and under protocols approved by the OSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Caspase assays

Apoptotic changes in MV4-11, KG1, and KG1a cell lines infected with lentiviral miR-3151, antagomiR-3151, BAALC, or scramble control were analyzed using the chemiluminescent Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay (Promega) 72 hours after puromycin selection, using 20,000 cells in duplicate of three biological replicates, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blotting assays

Western blotting was performed according to standard procedures. Antibodies used were p53 (#sc-126, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), caspase 3 (#9665S, Cell Signaling), and actin (#sc-1616, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

ChIP assays

ChIP assays for determination of histone modifications and Pol II enrichment were performed using the SimpleChiP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (#9003, Cell Signaling) on KG1a cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR-based analysis was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR primers to test for enrichment on TSS-3151 and TSS-BAALC were identical with the TSS cloning primers listed in table S3 without the cloning tail.

Primers for RPL30 (#7014P) and alpha satellite repeats (#4486S) were purchased from Cell Signaling. All antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling: histone H3 (D2B12) XP (R) (#4620S), tri-methyl-histone H3 (K4, C42D8; #9751S), Rpbl C-terminal domain (also known as Pol II; 4H8, #2629S), and normal IgG rabbit (#2729).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Nuclear proteins were extracted from KG1a cells 3 hours after treatment with 100 nM bortezomib (sc-217785, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or vehicle (100 nM DMSO) using the Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Knockdown of SP1 was performed using 100 nM ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool human SP1 (#L-026959-00, Thermo Scientific Dharmacon) for transfection of 6 million KG1a cells. Nuclear extracts were harvested and processed 24 hours after electroporation. All oligonucleotide sequences used for the EMSA analysis are listed in table S4. For EMSA performance, the Thermo Scientific LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Pierce/Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Antibodies used were NF-κB p65 (#sc-71677, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and SP1 (#sc-59, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Statistical methods

Data were presented as means ± SD of at least three independent experiments unless otherwise indicated and analyzed by two-tailed or one-tailed Student’s t test. The means and SDs were calculated and displayed in bar graphs as the height and the corresponding error bar, respectively. Mouse survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival curves were compared by the log-rank test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For determination of miR-3151 abundance and BAALC and TP53 expression, the relative abundances of miR-3151 and BAALC and TP53 transcripts were determined by qRT-PCR. For categorization of the patients and cell lines into high and low miR-3151 and BAALC expressers, the median cut was determined on the basis of the expression levels of the respective genes of the eight CN-AML patients of the patient cohort (see Table 2).

Bioinformatics analyses

The putative TSSs for miR-3151 and BAALC were identified by computational analysis of 2000 bp of upstream sequence of both miR-3151 and BAALC using the fruitfly.org algorithm (eukaryotic sequence with a score cutoff of 0.80 for promoter prediction). The output sequence (50 bp in length) was then tested for putative transcription factor binding sites using tfsearch.org (50 bp predicted TSS ± 20 bp flanking sequence with a score cutoff of 70.0; table S1).

The previously derived GEP associated with high abundance of miR-3151 in 179 older CN-AML patients was imported into the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis program (Ingenuity IPA, content version: 11904312). The analysis for Top Canonical Pathways is provided in the Summary of Analysis in the output data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Liyanarachchi for help with the statistical analyses, K. Jazdzewski for support and advice, J. Lockman for technical support, D. Bucci of the OSU and CALGB Leukemia Tissue Bank at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center (Columbus, OH) for sample processing and storage services, and The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Nucleic Acid and Microarray Shared Resources for technical support.

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (grants CA101140, CA114725, CA140158, CA31946, CA33601, CA16058, CA77658, CA095512, and CA129657), the Coleman Leukemia Research Foundation (A.-K.E.), and the Pelotonia Fellowship Program (A.-K.E.).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS www.sciencesignaling.org/cgi/content/full/7/321/ra36/DC1

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: A.-K.E., S.S., C.J.W., X.H., R.P., K.W.H., B.L., T.M.J., and R.S. conceived and performed the experiments; C.D.B., G.M., and A.d.l.C. supervised the experiments; J.M. and W.E.C. supplied the MeWo and A375 cell lines; G.M., D.P., and W.E.C. gave advice on experimental procedures; A.-K.E., A.d.l.C., and C.D.B. wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Burnett A, Wetzler M, Löwenberg B. Therapeutic advances in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:487–494. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estey E, Döhner H. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 2006;368:1894–1907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fröhling S, Schlenk RF, Kayser S, Morhardt M, Benner A, Döhner K, Döhner H, German-Austrian AML Study Group Cytogenetics and age are major determinants of outcome in intensively treated acute myeloid leukemia patients older than 60 years: Results from AMLSG trial AML HD98-B. Blood. 2006;108:3280–3288. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mrózek K, Marcucci G, Paschka P, Whitman SP, Bloomfield CD. Clinical relevance of mutations and gene-expression changes in adult acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics: Are we ready for a prognostically prioritized molecular classification? Blood. 2007;109:431–448. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcucci G, Haferlach T, Döhner H. Molecular genetics of adult acute myeloid leukemia: Prognostic and therapeutic implications. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:475–486. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanner SM, Austin JL, Leone G, Rush LJ, Plass C, Heinonen K, Mrózek K, Sill H, Knuutila S, Kolitz JE, Archer KJ, Caligiuri MA, Bloomfield CD, de la Chapelle A. BAALC, the human member of a novel mammalian neuroectoderm gene lineage, is implicated in hematopoiesis and acute leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:13901–13906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241525498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldus CD, Martus P, Burmeister T, Schwartz S, Gökbuget N, Bloomfield CD, Hoelzer D, Thiel E, Hofmann WK. Low ERG and BAALC expression identifies a new subgroup of adult acute T-lymphoblastic leukemia with a highly favorable outcome. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:3739–3745. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kühnl A, Gökbuget N, Stroux A, Burmeister T, Neumann M, Heesch S, Haferlach T, Hoelzer D, Hofmann WK, Thiel E, Baldus CD. High BAALC expression predicts chemoresistance in adult B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:3737–3744. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-241943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schrama D, Keller G, Houben R, Ziegler CG, Vetter-Kauczok CS, Ugurel S, Becker JC. BRAFV600E mutations in malignant melanoma are associated with increased expressions of BAALC. J. Carcinog. 2008;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agaram NP, Laquaglia MP, Ustun B, Guo T, Wong GC, Socci ND, Maki RG, DeMatteo RP, Besmer P, Antonescu CR. Molecular characterization of pediatric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:3204–3215. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldus CD, Tanner SM, Ruppert AS, Whitman SP, Archer KJ, Marcucci G, Caligiuri MA, Carroll AJ, Vardiman JW, Powell BL, Allen SL, Moore JO, Larson RA, Kolitz JE, de la Chapelle A, Bloomfield CD. BAALC expression predicts clinical outcome of de novo acute myeloid leukemia patients with normal cytogenetics: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Blood. 2003;102:1613–1618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bienz M, Ludwig M, Leibundgut EO, Mueller BU, Ratschiller D, Solenthaler M, Fey MF, Pabst T. Risk assessment in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and a normal karyotype. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:1416–1424. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eid MA, Attia M, Abdou S, El-Shazly SF, Elahwal L, Farrag W, Mahmoud L. BAALC and ERG expression in acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype: Impact on prognosis. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2010;32:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2009.01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwind S, Marcucci G, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Mrózek K, Holland KB, Margeson D, Becker H, Whitman SP, Wu YZ, Metzeler KH, Powell BL, Kolitz JE, Carter TH, Moore JO, Baer MR, Carroll AJ, Caligiuri MA, Larson RA, Bloomfield CD. BAALC and ERG expression levels are associated with outcome and distinct gene and microRNA expression profiles in older patients with de novo cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Blood. 2010;116:5660–5669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-290536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heuser M, Berg T, Kuchenbauer F, Lai CK, Park G, Fung S, Lin G, Leung M, Krauter J, Ganser A, Humphries RK. Functional role of BAALC in leukemogenesis. Leukemia. 2012;26:532–536. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovat F, Valeri N, Croce CM. MicroRNAs in the pathogenesis of cancer. Semin. Oncol. 2011;38:724–733. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez A, Griffiths-Jones S, Ashurst JL, Bradley A. Identification of mammalian microRNA host genes and transcription units. Genome Res. 2004;14:1902–1910. doi: 10.1101/gr.2722704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffiths-Jones S. Annotating noncoding RNA genes. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2007;8:279–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.8.080706.092419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stark MS, Tyagi S, Nancarrow DJ, Boyle GM, Cook AL, Whiteman DC, Parsons PG, Schmidt C, Sturm RA, Hayward NK. Characterization of the melanoma miRNAome by deep sequencing. PLOS One. 2010;5:e9685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schotte D, Akbari A, Moqadam F, Lange-Turenhout EAM, Chen C, van Ijcken WF, Pieters R, den Boer ML. Discovery of new microRNAs by small RNAome deep sequencing in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:1389–1399. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisfeld AK, Marcucci G, Maharry K, Schwind S, Radmacher MD, Nicolet D, Becker H, Mrózek K, Whitman SP, Metzeler KH, Mendler JH, Wu YZ, Liyanarachchi S, Patel R, Baer MR, Powell BL, Carter TH, Moore JO, Kolitz JE, Wetzler M, Caligiuri MA, Larson RA, Tanner SM, de la Chapelle A, Bloomfield CD. miR-3151 interplays with its host gene BAALC and independently impacts on outcome of patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:249–258. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-408492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine AJ. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;8:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yonish-Rouach E, Resnitzky D, Lotem J, Sachs L, Kimchi A, Oren M. Wild-type p53 induces apoptosis of myeloid leukaemic cells that is inhibited by interleukin-6. Nature. 1991;352:345–347. doi: 10.1038/352345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. p53 function and dysfunction. Cell. 1992;70:523–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ranganathan P, Yu X, Na C, Santhanam R, Shacham S, Kauffman M, Walker A, Klisovic R, Blum W, Caligiuri M, Croce CM, Marcucci G, Garzon R. Preclinical activity of a novel CRM1 inhibitor in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:1765–1773. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-423160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu S, Wu LC, Pang J, Santhanam R, Schwind S, Wu YZ, Hickey CJ, Yu J, Becker H, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Li C, Whitman SP, Mishra A, Stauffer N, Eiring AM, Briesewitz R, Baiocci RA, Chan KK, Paschka P, Caligiuri MA, Byrd JC, Croce CM, Bloomfiled CD, Perrotti D, Garzon R, Marcucci G. Sp1/NFκB/HDAC/miR-29b regulatory network in KIT-driven myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:333–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blum W, Schwind S, Tarighat SS, Geyer S, Eisfeld AK, Whitman S, Walker A, Klisovic R, Byrd JC, Santhanam R, Wang H, Curfman JP, Devine SM, Jacob S, Garr C, Kefauver C, Perrotti D, Chan KK, Bloomfield CD, Caligiuri MA, Grever MR, Garzon R, Marcucci G. Clinical and pharmacodynamic activity of bortezomib and decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;119:6025–6031. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-413898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oszolak F, Poling LL, Wang Z, Liu H, Liu XS, Roeder GH, Zhang X, Song JS, Fisher DE. Chromatin structure analyses identify miRNA promoters. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3172–3183. doi: 10.1101/gad.1706508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mas Monteys A, Spengler RM, Wan J, Tecedor L, Lennox KA, Xing Y, Davidson BL. Structure and activity of putative intronic miRNA promoters. RNA. 2010;16:495–505. doi: 10.1261/rna.1731910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisfeld AK, Marcucci G, Liyanarachchi S, Döhner K, Schwind S, Maharry K, Leffel B, Döhner H, Radmacher MD, Bloomfield CD, Tanner SM, de la Chapelle A. Heri-table polymorphism predisposes to high BAALC expression in acute myeloid leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:6668–6673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203756109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.