Abstract

Background

Peripheral neuropathy is the major dose-limiting side effect of cisplatin and oxaliplatin, and there are currently no effective treatments available. The aim of this study was to assess the pharmacological mechanisms underlying chemotherapy-induced neuropathy in novel animal models based on intraplantar administration of cisplatin and oxaliplatin and to systematically evaluate the analgesic efficacy of a range of therapeutics.

Methods

Neuropathy was induced by a single intraplantar injection of cisplatin or oxaliplatin in C57BL/6J mice and assessed by quantification of mechanical and thermal allodynia. The pharmacological basis of cisplatin-induced neuropathy was characterized using a range of selective pharmacological inhibitors. The analgesic effects of phenytoin, amitriptyline, oxcarbazepine, mexiletine, topiramate, retigabine, gabapentin, fentanyl, and Ca2+/Mg2+ were assessed 24 hours after induction of neuropathy.

Results

Intraplantar administration of cisplatin led to the development of mechanical allodynia, mediated through Nav1.6-expressing sensory neurons. Unlike intraplantar injection of oxaliplatin, cold allodynia was not observed with cisplatin, consistent with clinical observations. Surprisingly, only fentanyl was effective at alleviating cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia despite a lack of efficacy in oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia. Conversely, lamotrigine, phenytoin, retigabine, and gabapentin were effective at reversing oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia but had no effect on cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia. Oxcarbazepine, amitriptyline, mexiletine, and topiramate lacked efficacy in both models of acute chemotherapy-induced neuropathy.

Conclusion

This study established a novel animal model of cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia consistent with the A-fiber neuropathy seen clinically. Systematic assessment of a range of therapeutics identified several candidates that warrant further clinical investigation.

Keywords: analgesia, chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, cisplatin, Nav1.6, oxaliplatin

Platinum-based chemotherapeutics are widely used in combination with other agents for treatment of many solid tumors. Cisplatin is typically used to treat head, neck, lung, ovarian, and testicular cancers, whereas oxaliplatin is mainly used for treating advanced colorectal cancer. Both agents are associated with clinically distinct, dose-limiting peripheral neuropathy. However, the pharmacological basis underlying their different effects is poorly understood, and the efficacies of clinically available analgesics have not been systematically investigated.

The incidence and severity of cisplatin neuropathy is dose dependent and occurs during or after cessation of treatment at cumulative doses >300 mg/m2.1–3 It has a “stocking-glove” distribution that affects the distal parts of the lower and upper limbs and produces symptoms including paresthesias, dysesthesias, and loss of vibration sense.2–5 Electrophysiological and morphological studies indicate that the neuropathy caused by cisplatin predominately affects large sensory neurons.1–3 The chronic nature of cisplatin neuropathy, which can persist for months after cessation of treatment, is thought to be due to accumulation of platinum compounds in the dorsal root ganglia.6,7 In contrast, oxaliplatin neuropathy can be classified as being either acute or chronic. Acute neuropathy affects 80%–96% of patients and can occur immediately after infusion and last several days.8,9 Symptoms of acute neuropathy include cold-induced dysesthesias and paresthesias that have a stocking-glove distribution similar to cisplatin, with additional perioral effects8,10,11 due to a direct effect of oxaliplatin on ion channels including voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels.12–14 Chronic neuropathy, on the other hand, is dose dependent, occurs after cumulative doses greater than 750 mg/m2, and is similar to cisplatin with the addition of changes in proprioception.15,16

The major dose-limiting side effect of cisplatin- and oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy can lead to cumulative dose reductions or result in early treatment cessation with a negative impact on cancer treatment.1,8 This problem is compounded by a lack of effective treatment for either condition. The aim of this study was to systematically evaluate a range of analgesic therapeutics for platinum-based chemotherapy-induced neuropathy using novel animal models.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Cisplatin and oxaliplatin were obtained from Sigma Aldrich and dissolved in 5% glucose/H2O to a stock solution of 1 mg/mL. Tetrodotoxin (TTX) was from Tocris Bioscience, and ProTxII was from Peptides International. The μ-conotoxins GIIIA and TIIIA were synthesized by Boc chemistry using methods described previously.17 All other reagents were from Sigma Aldrich unless otherwise stated. Peptides were diluted in 0.1%–0.3% albumin in phosphate-buffered saline to avoid adsorption to plastic surfaces. All other reagents were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline.

Animals

For behavioral assessment of cisplatin and oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy, we used adult male C57BL/6J mice aged 6–8 weeks. Mice were housed in groups of 3 or 4 per cage under 12 hour light-dark cycles and fed standard rodent chow and water ad libitum.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval for in vivo experiments in animals was obtained from the University of Queensland animal ethics committee. Experiments involving animals were conducted in accordance with the Animal Care and Protection Act Qld (2001), the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes, 8th edition (2013), and the International Association for the Study of Pain Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Research.

Induction of Chemotherapy-induced Peripheral Neuropathy

A single dose of oxaliplatin (40 μg) or cisplatin (40 μg, 4 μg, or 0.4 μg) was administered by shallow subcutaneous injection to the left hind paw (intraplantar injection) under 3% isoflurane anesthesia. This led to a rapid induction of neuropathy that was evident within 1 hour of injection. No adverse effects, such as inflammation or ulceration, were observed at the site of injection, and injection of solvent (5% glucose/H2O) alone caused no mechanical or thermal allodynia.

Behavioral Assessment

Quantification of mechanical and thermal allodynia was performed by a blinded observer unaware of any treatments administered. Mechanical allodynia was assessed using an electronic von Frey apparatus (MouseMet Electronic von Frey, TopCat Metrology). Mice were habituated in individual mouse runs for at least 10 minutes prior to testing. Pressure was applied to the left hind paw through a soft-tipped probe and increased slowly at a force rise rate of 1 g/s. The force that elicited paw withdrawal was determined using the MouseMet Software. The test was repeated 4 times at 5-minute intervals. The force that elicited paw withdrawal from each of the 4 tests was averaged and designated as the paw-withdrawal threshold. Thermal allodynia was quantified by counting the number of paw lifts, licks, shakes, and flinches on a temperature-controlled Peltier plate (Hot/Cold Plate, Ugo Basile) over a 5-minute period at the non-noxious temperatures 10°C (cold allodynia) and 42°C (heat allodynia).

Effect of Pharmacological Modulators and Clinical Compounds

The effect of pharmacological modulators and clinical compounds was assessed 24 hours after administration of the chemotherapeutic agents. To determine which Nav channel subtypes contributed to the development of cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy, TTX (3 μM), ProTxII (3 nM), GIIIA (10 μM), and TIIIA (10 μM) were administered by intraplantar injection in a volume of 20 μL 15 minutes prior to behavioral assessments. No systemic effects, including ataxia, altered gait, or motor paralysis, were apparent in any mice at the doses used. To assess the anti-allodynic effects of clinical compounds during oxaliplatin- and cisplatin-induced neuropathy, drugs were administered by intraperitoneal injection at the doses stated in a volume of 10 μL/g bodyweight 1 hour prior to behavioral assessment. The doses of clinical compounds used in this study are based on the maximum tolerated doses routinely used in the literature and are approximately equivalent to ceiling doses used in humans.18–23

Motor Assessment

To assess the effects of analgesic therapeutics on motor performance, the following numerical scale was used: 0, normal activity; 1, reduced activity and closing eyes; 2, reduced activity, closing eyes, and incoordination. A blinded observer, unaware of the treatments received, performed the scoring.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Data were plotted and analyzed using GraphPad PrismTM, Version 6.0a. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05 and was determined by 1-way ANOVA analysis with the Dunnett' posttest.

Results

A Mouse Model of Chemotherapy-induced Mechanical Allodynia Based on Intraplantar Injection of Cisplatin

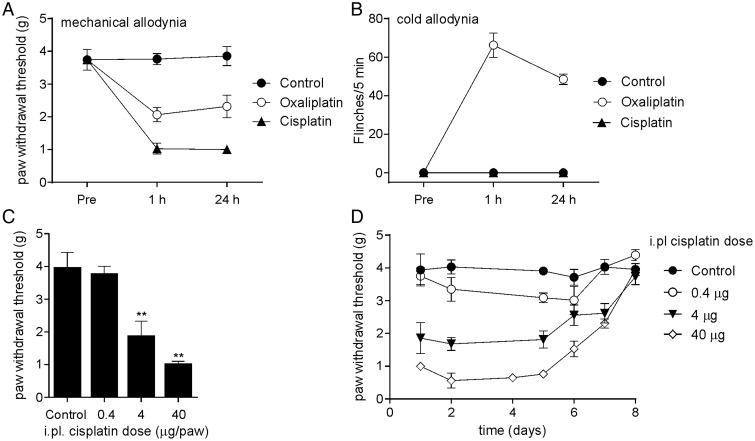

We recently established an animal model of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy based on intraplantar injection of oxaliplatin.13 To evaluate the effects of intraplantar injection of the related chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin, we established a comparable model. Intraplantar injection of cisplatin caused rapid development of mechanical allodynia as evidenced by a significant reduction in paw-withdrawal threshold to mechanical stimulation compared with control (Fig. 1A, 24 h; control, 3.9 ± 0.3 g; oxaliplatin 40 μg, 2.3 ± 0.3 g; cisplatin 40 μg, 1.0 ± 0.1 g; P < .05).

Fig. 1.

An animal model of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy based on intraplantar injection of cisplatin. (A) Intraplantar injection of cisplatin (40 μg/paw) caused mechanical allodynia as evidenced by a significant reduction in paw-withdrawal threshold to mechanical stimulation compared with control (5% glucose/H2O). Mechanical allodynia developed rapidly and was apparent within 1 hour after injection. The mechanical allodynia caused by cisplatin was much more pronounced than that caused by an equivalent dose of intraplantar oxaliplatin. (B) Intraplantar injection of cisplatin (40 μg/paw) did not cause any nocifensive responses upon exposure to a temperature-controlled surface at 10°C, unlike an equivalent dose of intraplantar oxaliplatin. (C) A single intraplantar injection of cisplatin (0.4–40 μg/paw) caused mechanical allodynia dose dependently (data taken at 24 h). (D) Single intraplantar injection of cisplatin caused persistent mechanical allodynia lasting for several days. Data are represented as mean ± SEM 4–14 mice/group. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired Student t test; **P < .01; **P < .05 compared with control.

In contrast to intraplantar injection of oxaliplatin, which caused cold allodynia as evidenced by paw shaking, lifting, licking, and flinching at 10°C (Fig. 1B; 24 h; control, 0 ± 0 flinches/5 min; oxaliplatin 40 μg, 48.5 ± 2.7 flinches/5 min), intraplantar injection of cisplatin did not cause observable nocifensive behaviors on a temperature-controlled surface at 10°C (cisplatin 40 μg, 0 ± 0 flinches/5 min), consistent with clinical observations that cold allodynia does not appear to develop in cisplatin-induced neuropathy.10 Intraplantar injection of cisplatin caused a mild, short-lasting heat allodynia at 42°C (5 ± 2 flinches/5 min) that was apparent 15 minutes after injection and resolved by 1 hour. Intraplantar injection of cisplatin (0.4–40 μg) caused dose-dependent mechanical allodynia that was evident within 1 hour of injection and persisted for 7 days after a single injection of the highest dose (40 μg; Fig. 1C and D).

Cisplatin-induced Mechanical Allodynia Is Mediated Through Nav1.6-expressing Peripheral Sensory Fibers

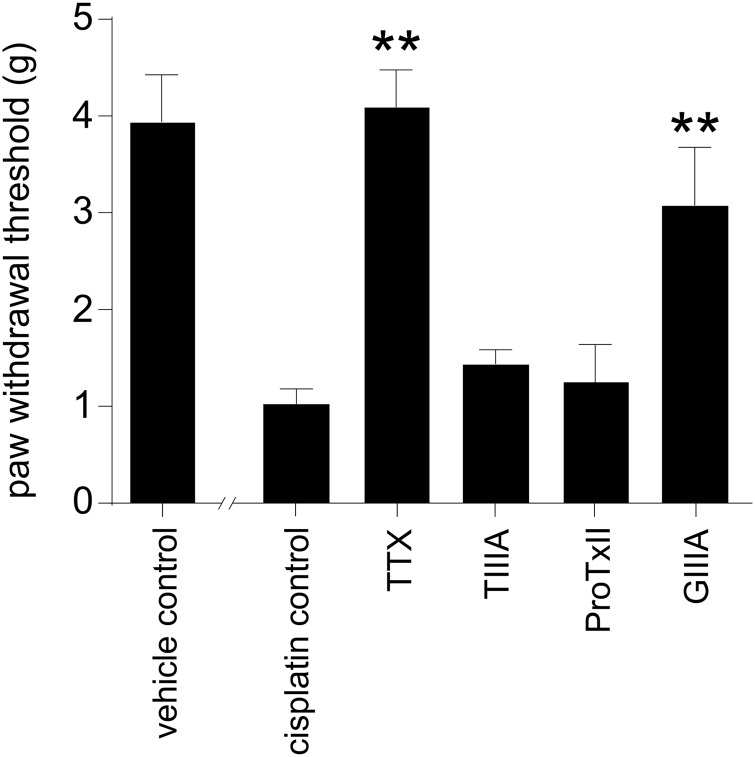

We have previously shown that cold allodynia induced by intraplantar injection of oxaliplatin is mediated through sensory neurons expressing Nav1.6.13 Similarly, cisplatin-induced neuropathy is reported to arise from damage to large, myelinated sensory neurons. We thus sought to assess the effect of subtype-selective Nav inhibitors on cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia. Ipsilateral intraplantar administration of TTX (3 μM) completely reversed mechanical allodynia (4.1 ± 0.4 g), indicating that pain signaling associated with cisplatin neuropathy is mediated through TTX-sensitive Nav isoforms (Fig. 2). Intraplantar administration of the Nav1.4/Nav1.2/Nav1.1 inhibitor TIIIA (10 μM) or the Nav1.7 specific inhibitor ProTxII (3 nM) did not have a significant effect on mechanical allodynia, indicating that these subtypes play no more than a minor role. However, intraplantar administration of GIIIA (10 μM), which additionally inhibits Nav1.6 compared with TIIIA but has no effect on Nav1.7/Nav1.3, significantly increased the paw-withdrawal threshold compared with cisplatin control (GIIIA, 3.1 ± 0.6 g; control, 1.0 ± 0.2 g; P < .05). This observation indicates a role of Nav1.6-expressing fibers in the conduction of cisplatin-induced neuropathic pain, consistent with the A-fiber neuropathy observed in the clinic.

Fig. 2.

Nav isoforms involved in the development of mechanical allodynia after intraplantar injection of cisplatin. Mechanical allodynia induced by intraplantar injection of cisplatin (24 h after injection of cisplatin 40 μg/paw) was completely reversed by intraplantar injection of TTX (3 μM). Cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia was not significantly inhibited after intraplantar administration of the Nav1.2/Nav1.1 inhibitor TIIIA (10 μM) or the Nav1.7 specific inhibitor ProTxII (3 nM). Intraplantar administration of Nav1.1/Nav1.6 inhibitor GIIIA (10 μM) significantly increased the paw-withdrawal threshold compared with cisplatin control. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 5–10 mice/group. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA with the Dunnett's posttest; ** P < .01; * P < .05 compared with control.

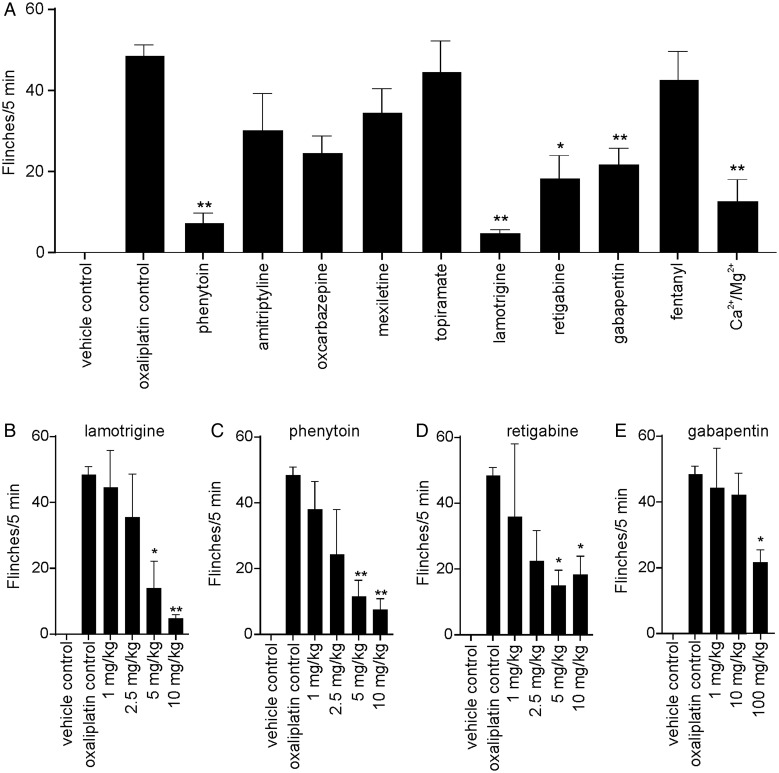

Analgesic Treatment of Oxaliplatin-induced Cold Allodynia

Peripheral neuropathy induced by oxaliplatin and cisplatin is a major dose-limiting side effect that is difficult to manage clinically.24 Since our models are consistent with the clinically described A-fiber pathology and symptomatology,1,12 we assessed the anti-allodynic effect of a range of analgesics in oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia. Lamotrigine and phenytoin were the most effective compounds tested, virtually abolishing all cold pain behaviors (lamotrigine 10 mg/kg, 90.0% ± 2.3% inhibition; phenytoin 10 mg/kg, 84.9% ± 5.5% inhibition; Fig. 3A). Ca2+/Mg2+ (0.05 mmol/kg; 74.2% ± 11.3% inhibition), retigabine (10 mg/kg; 62.1% ± 12.0% inhibition), and gabapentin (100 mg/kg; 55.5% ± 8.7%) also reduced cold pain behaviors significantly (P < .05). Amitriptyline (3 mg/kg; 37.8% ± 19.2% inhibition), oxcarbazepine (10 mg/kg; 49.1% ± 9.0% inhibition), mexiletine (10 mg/kg; 28.9% ± 12.7% inhibition), topiramate (50 mg/kg; 8.1% ± 16.2% inhibition), and fentanyl (0.2 mg/kg; 12.4% ± 14.7%) had no significant effect on cold allodynia. At these doses, motor impairment was only apparent for amitriptyline.

Fig. 3.

Anti-allodynic treatment of oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia (A) Cold allodynia induced by intraplantar injection of oxaliplatin (24 h after injection of oxaliplatin 40 μg/paw) was significantly decreased by intraperitoneal injection of (in order of efficacy) lamotrigine (10 mg/kg), phenytoin (10 mg/kg), Ca2+/Mg2+ (0.05 mmol/kg), retagabine (10 mg/kg), and gabapentin (100 mg/kg). Amitriptyline (3 mg/kg), oxcabazepine (10 mg/kg), mexiletine (10 mg/kg), topiramate (50 mg/kg), and fentanyl (0.2 mg/kg) had no significant anti-allodynic effect. Dose response of clinical compounds that reduced oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia by at least 50%. (B and C) Lamotrigine and phenytoin (1–10 mg/kg) dose dependently reduced cold allodynia with similar potency and efficacy. (D) Reducing the dose of retigabine did not lead to a significant decrease in efficacy (2.5–10 mg/kg); however, it was not as efficacious as lamotrigine and phenytoin at equipotent doses. (E) Reducing the dose of gabapentin diminished the anti-allodynic effect. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 5–10 mice/group. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA with the Dunnett's posttest; ** P < .01; * P < .05 compared with control.

Dose-response studies of lamotrigine and phenytoin (1–10 mg/kg) showed that both drugs reduced oxaliplatin-induced cold-pain behaviors with similar efficacy and potency (Fig. 3B and C), with significant analgesia evident at 5 and 10 mg/kg for both compounds. Retigabine also significantly decreased oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia (5–10 mg/kg) (Fig. 3D). Gabapentin caused partial analgesia at the highest dose tested (100 mg/kg), but reducing the dose of gabapentin dramatically diminished the anti-allodynic effect (Fig. 3E).

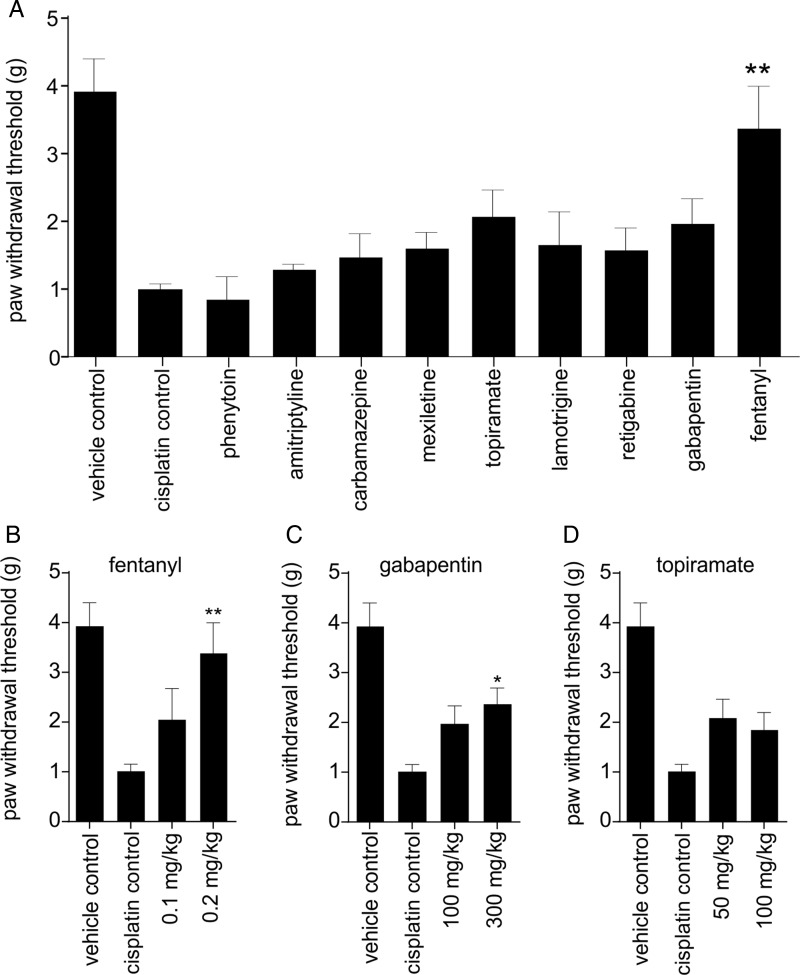

Analgesic Treatment of Cisplatin-induced Mechanical Allodynia

We next assessed the effectiveness of the analgesic compounds in the intraplantar cisplatin model (Fig. 4A). Surprisingly, none of the compounds found to be efficacious in oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia were effective in alleviating cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia. Fentanyl (0.1 and 0.2 mg/kg) increased the paw-withdrawal threshold dose dependently, with 0.2 mg/kg being the most effective dose (0.2 mg/kg; 3.4 ± 0.6 g; P < .05) (Fig. 4B). Topiramate (50 mg/kg; 2.1 ± 0.4 g; P > .05) and gabapentin (100 mg/kg; 2.0 ± 0.4g; P > .05) only partially reversed cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia. Increasing the dose of gabapentin did increase the paw-withdrawal threshold significantly (300 mg/kg; 2.4 ± 0.3 g; P < .05); however, motor impairment was observed at this higher dose (Fig. 4C). Even at these high doses, gabapentin was still less effective compared with fentanyl. Increasing the dose of topiramate did not result in any further improvement in the paw-withdrawal threshold (100 mg/kg; 1.9 ± 0.4 g; Fig. 4D). Phenytoin (10 mg/kg; 0.9 ± 0.4 g), amitriptyline (3 mg/kg; 1.3 ± 0.1 g), carbamazepine (10 mg/kg; 1.5 ± 0.4 g), mexiletine (10 mg/kg; 1.6 ± 0.3 g), lamotrigine (10 mg/kg; 1.7 ± 0.5 g), and retigabine (10 mg/kg; 1.6 ± 0.3 g) had no significant effect on pain behavior.

Fig. 4.

Anti-allodynic treatment of cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia (A) Mechanical allodynia induced by intraplantar injection of cisplatin (24 h after injection of cisplatin 40 μg/paw) was significantly improved by intraperitoneal administration of fentanyl (0.2 mg/kg). Phenytoin (10 mg/kg), amitriptyline (3 mg/kg), carbamazepine (10 mg/kg), mexiletine (10 mg/kg), topiramate (50 mg/kg), lamotrigine (10 mg/kg), retigabine (10 mg/kg), and gabapentin (100 mg/kg) had no significant anti-allodynic effect. Dose response of clinical compounds that reduced cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia by at least 50%. (B) Fentanyl (0.1 and 0.2 mg/kg) dose dependently increased the paw-withdrawal threshold, with 0.2 mg/kg being the most effective dose. (C) Increasing the dose of gabapentin to 300 mg/kg led to a significant increase in the paw-withdrawal threshold; however, motor impairment was observed at this dose. (D) Increasing the dose of topiramate did not lead to any further increases in the paw-withdrawal threshold. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 5–10 mice/group. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA with the Dunnett's posttest; ** P < .01; * P < .05 compared with control.

Discussion

Administration of cisplatin and oxaliplatin leads to the development of dose-dependent neuropathy. However, despite the significant impact on quality of life and therapeutic outcomes, there are currently no effective treatments directed at reducing functional impairment caused by chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. In order to address this issue, we systematically characterized and compared the analgesic efficacy of a range of clinically used compounds in animal models of platinum-based chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. While isolated compounds have previously been tested in comparable animal models, a systematic comparison of a range of clinically used adjuvant analgesics in the same model has never been done before.

We have previously established a novel animal model of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy based on a single intraplantar injection of oxaliplatin and found that this model reproduced the clinical presentation and time course of acute oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy, consistent with a direct excitatory effect of oxaliplatin on sensory nerve endings.13 Thus, we sought to characterize the effects of cisplatin after intraplantar administration because this causes exposure of peripheral sensory nerve endings to high concentrations of cisplatin, avoids systemic side effects, and permits quantification of unilateral pain behavior. Consistent with previously reported animal models of cisplatin, we observed the development of mechanical, but not thermal, allodynia after intraplantar injection of cisplatin, with the onset of allodynia being more rapid than after repeated systemic administration of similar doses.25,26 This was likely a reflection of the high local concentration of cisplatin at the sensory nerve endings, which was achieved by intraplantar injection, as cisplatin-induced neuropathy is believed to arise from accumulation of the chemotherapeutic agent in peripheral sensory neurons through copper transporters.27 Intraplantar injection of oxaliplatin or cisplatin directly exposes peripheral sensory nerve endings to high concentrations of platinum-based chemotherapeutic agents,28–30 modeling the accumulation that occurs after intravenous administration. Our model accurately reflects the clinical presentation of cisplatin-induced pain in which mechanical thresholds, but not cold detection and cold pain thresholds, are typically altered and thus supports the validity of our approach.1,10 While preferential accumulation of cisplatin in dorsal root ganglia correlates with the degree of neurotoxicity, the behavioral consequences of intraplantar administration observed here are consistent with the channelopathy hypothesis, which implicates platinum-induced ion channel dysfunction as a pathophysiological factor that contributes to the development of nerve dysfunction and clinical neuropathy.

Clinically, both cisplatin- and oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy have been described as A-fiber neuropathies, with decreased vibration thresholds and morphological changes observed in large sensory neurons, while small nociceptive fibers appear to be unaffected.3 We recently reported that oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia is mediated by Nav1.6-expressing pain pathways,13 consistent with expression of this Nav isoform in large myelinated sensory neurons, while small unmyelinated C fibers express Nav1.7, 1.8, and 1.9.31,32 Accordingly, we found no contribution of Nav1.7, Nav1.8, or Nav1.9 to cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia, while pharmacological inhibition of Nav1.6 significantly reduced pain behavior. There is a growing body of evidence supporting a role for Nav1.6 in the pathogenesis of pain, with pharmacological activation of Nav1.6 in mice causing spontaneous pain and mechanical allodynia.13 Nav1.6 has also been shown to be important in the development of ciguatoxin-induced cold allodynia and mechanical allodynia due to localized inflammation of dorsal root ganglia.23,33 In addition, Nav1.6 is upregulated in dorsal root ganglia neurons in type II diabetes, suggesting it may also have a role in the development of diabetic neuropathy.34

Despite the significant impact of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy on patient outcomes, there are currently no effective treatments directed at reducing functional impairment, and systematic comparison of the analgesic efficacy of clinically available compounds is lacking. Thus, we sought to systemically test and compare a range of clinically used compounds, including those with reported activity at Nav isoforms, for anti-allodynic effects. Surprisingly, only fentanyl was effective at alleviating cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia, while it lacked efficacy in oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia. Conversely, lamotrigine, phenytoin, retigabine, and gabapentin were effective at decreasing oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia but had no effect on cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia, while oxcarbazepine, amitriptyline, mexiletine, and topiramate lacked efficacy in both models of acute chemotherapy-induced neuropathy.

Although Nav1.6-expressing neurons mediate platinum-based chemotherapy-induced acute neuropathy, the precise pathophysiological mechanisms by which oxaliplatin and cisplatin selectively affect large myelinated sensory neurons to elicit cold or mechanical allodynia, respectively, remain unclear. Both compounds likely accumulate in sensory neurons through active transport mechanisms and elicit apoptotic morphology changes and abnormal neuronal excitability.35–39 Oxaliplatin is known to inhibit potassium channels in addition to activating sodium channels on A-fibers,40 an effect that appears to contribute to development of cold allodynia. Activation of Nav1.6 alone is not sufficient to elicit cold allodynia and requires concomitant inhibition of potassium channels.13 Accordingly, compounds with mixed activity at Nav and Kv are most likely to be effective for treating oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia. Indeed, we found the most effective compounds to be the anticonvulsants lamotrigine, phenytoin, and retigabine, all of which have mixed activity at Nav and Kv,41–43 while drugs with activity only at Nav were not consistently effective (particularly for cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia). Given the expression pattern of Nav1.6 at the nodes of Ranvier, this isoform may be difficult to target therapeutically because it is also expressed on motor neurons, and loss of function mutations of Nav1.6 in mice lead to hind limb paralysis.44 Accordingly, given the absence of motor effects at the doses used in this study, an alternate explanation for the lack of efficacy of Nav inhibitors may be that the clinical compounds were not able to reach sufficient concentrations to inhibit Nav1.6 in peripheral sensory neurons, as local administration of the Nav1.6 inhibitor GIIIA was able to attenuate mechanical allodynia.

It is known that oxaliplatin has an excitatory effect on ion channels, including Nav1.6, and that Nav1.6 colocalizes with the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger at sites of axonal injury.45 Persistent sodium current, driven by persistent activation of sodium channels, has been shown to reverse the flow of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger.46 This results in a damaging influx of calcium ions that are capable of causing axonal degeneration and provides an alternate mechanism for oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy. Accordingly, there is growing evidence to suggest that Ca2+/Mg2+ infusions may be effective in treating oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy without affecting its antitumor activity47,48 based on the stabilizing effect of extracellular calcium on neuronal membranes and excitability.49 Our results are consistent with these findings, as Ca2+/Mg2+ was effective at decreasing oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia. However, given that lamotrigine and phenytoin were found to be more effective than Ca2+/Mg2+ in our model, they warrant further investigation; neither has been tested in the clinic for the treatment of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy.

It remains to be determined if the compounds that showed activity in our models of acute chemotherapy-induced neuropathy are effective for managing chronic neuropathy. The acute phase of oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy is believed to be due to an excitatory effect of oxaliplatin on sensory nerve endings, whereas the chronic phase occurs due to an accumulation of platinum compounds in dorsal root ganglia neurons. However, there is evidence to suggest that the chronic phase may in fact be a continuum of the acute phase, as the severity of acute neuropathy is predictive for the development of chronic neuropathy.10,14 Therefore, treatment of acute neuropathy may not only provide relief of the troublesome cold-induced acute symptoms but also may prevent development of chronic neuropathy or reduce its severity.

In conclusion, this study has established a novel animal model for cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia that is consistent with the A-fiber neuropathy seen clinically and is mediated through Nav1.6-expressing sensory neurons. A systematic assessment of a range of clinical compounds in cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia and oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia revealed that lamotrigine, phenytoin, and retigabine effectively reversed oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia, while only fentanyl significantly reversed mechanical allodynia associated with cisplatin exposure. These analgesic therapeutics warrant further clinical investigation and may be useful for the management of acute or chronic chemotherapy-induced sensory neuropathy.

Funding

This work was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award (J.R.D.); a Ramaciotti Foundation Establishment Grant (I.V.); Cancer Council Queensland Grant (APP1023553, I.V.).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dalyara Mendonca de Matos for synthesizing the conopeptides GIIIA and TIIIA.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Krarup-Hansen A, Helweg-Larsen S, Schmalbruch H, et al. Neuronal involvement in cisplatin neuropathy: prospective clinical and neurophysiological studies. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 4):1076–1088. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krarup-Hansen A, Fugleholm K, Helweg-Larsen S, et al. Examination of distal involvement in cisplatin-induced neuropathy in man. An electrophysiological and histological study with particular reference to touch receptor function. Brain. 1993;116(Pt 5):1017–1041. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.5.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson SW, Davis LE, Kornfeld M, et al. Cisplatin neuropathy. Clinical, electrophysiologic, morphologic, and toxicologic studies. Cancer. 1984;54(7):1269–1275. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841001)54:7<1269::aid-cncr2820540707>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roelofs RI, Hrushesky W, Rogin J, et al. Peripheral sensory neuropathy and cisplatin chemotherapy. Neurology. 1984;34(7):934–938. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammack JE, Michalak JC, Loprinzi CL, et al. Phase III evaluation of nortriptyline for alleviation of symptoms of cis-platinum-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pain. 2002;98(1–2):195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gregg RW, Molepo JM, Monpetit VJ, et al. Cisplatin neurotoxicity: the relationship between dosage, time, and platinum concentration in neurologic tissues, and morphologic evidence of toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(5):795–803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hovestadt A, van der Burg ME, Verbiest HB, et al. The course of neuropathy after cessation of cisplatin treatment, combined with Org 2766 or placebo. J Neurol. 1992;239(3):143–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00833914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonard GD, Wright MA, Quinn MG, et al. Survey of oxaliplatin-associated neurotoxicity using an interview-based questionnaire in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2005;5 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-116. (16) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasetto LM, D'Andrea MR, Rossi E, et al. Oxaliplatin-related neurotoxicity: how and why? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;59(2):159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attal N, Bouhassira D, Gautron M, et al. Thermal hyperalgesia as a marker of oxaliplatin neurotoxicity: a prospective quantified sensory assessment study. Pain. 2009;144(3):245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Argyriou AA, Cavaletti G, Briani C, et al. Clinical pattern and associations of oxaliplatin acute neurotoxicity: a prospective study in 170 patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(2):438–444. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sittl R, Lampert A, Huth T, et al. Anticancer drug oxaliplatin induces acute cooling-aggravated neuropathy via sodium channel subtype Na(V)1.6-resurgent and persistent current. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(17):6704–6709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118058109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deuis JR, Zimmermann K, Romanovsky AA, et al. An animal model of oxaliplatin-induced cold allodynia reveals a crucial role for Nav1.6 in peripheral pain pathways. Pain. 2013;154(9):1749–1757. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnan AV, Goldstein D, Friedlander M, et al. Oxaliplatin and axonal Na+ channel function in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(15):4481–4484. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park SB, Lin CS, Krishnan AV, et al. Oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity: changes in axonal excitability precede development of neuropathy. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 10):2712–2723. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cersosimo RJ. Oxaliplatin-associated neuropathy: a review. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(1):128–135. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen KJ, Watson M, Adams DJ, et al. Solution structure of mu-conotoxin PIIIA, a preferential inhibitor of persistent tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(30):27247–27255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dost R, Rostock A, Rundfeldt C. The anti-hyperalgesic activity of retigabine is mediated by KCNQ potassium channel activation. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2004;369(4):382–390. doi: 10.1007/s00210-004-0881-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laughlin TM, Tram KV, Wilcox GL, et al. Comparison of antiepileptic drugs tiagabine, lamotrigine, and gabapentin in mouse models of acute, prolonged, and chronic nociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302(3):1168–1175. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.3.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minami K, Hasegawa M, Ito H, et al. Morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl exhibit different analgesic profiles in mouse pain models. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;111(1):60–72. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09139fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakaue A, Honda M, Tanabe M, et al. Antinociceptive effects of sodium channel-blocking agents on acute pain in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95(2):181–188. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fpj03087x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wieczorkiewicz-Plaza A, Plaza P, Maciejewski R, et al. Effect of topiramate on mechanical allodynia in neuropathic pain model in rats. Pol J Pharmacol. 2004;56(2):275–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmermann K, Deuis JR, Inserra MC, et al. Analgesic treatment of ciguatoxin-induced cold allodynia. Pain. 2013;154(10):1999–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albers JW, Chaudhry V, Cavaletti G, et al. Interventions for preventing neuropathy caused by cisplatin and related compounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2):CD005228. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005228.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park HJ, Stokes JA, Pirie E, et al. Persistent hyperalgesia in the cisplatin-treated mouse as defined by threshold measures, the conditioned place preference paradigm, and changes in dorsal root ganglia activated transcription factor 3: the effects of gabapentin, ketorolac, and etanercept. Anesth Analg. 2013;116(1):224–231. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31826e1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ta LE, Low PA, Windebank AJ. Mice with cisplatin and oxaliplatin-induced painful neuropathy develop distinct early responses to thermal stimuli. Mol Pain. 2009;5 doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-9. (9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu JJ, Kim Y, Yan F, et al. Contributions of rat Ctr1 to the uptake and toxicity of copper and platinum anticancer drugs in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85(2):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sprowl JA, Ciarimboli G, Lancaster CS, et al. Oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity is dependent on the organic cation transporter OCT2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(27):11199–11204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305321110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jong NN, Nakanishi T, Liu JJ, et al. Oxaliplatin transport mediated by organic cation/carnitine transporters OCTN1 and OCTN2 in overexpressing human embryonic kidney 293 cells and rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338(2):537–547. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.181297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lancaster CS, Sprowl JA, Walker AL, et al. Modulation of OATP1B-type transporter function alters cellular uptake and disposition of platinum chemotherapeutics. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(8):1537–1544. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caldwell JH, Schaller KL, Lasher RS, et al. Sodium channel Na(v)1.6 is localized at nodes of ranvier, dendrites, and synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(10):5616–5620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.090034797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukuoka T, Kobayashi K, Yamanaka H, et al. Comparative study of the distribution of the alpha-subunits of voltage-gated sodium channels in normal and axotomized rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510(2):188–206. doi: 10.1002/cne.21786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie W, Strong JA, Ye L, et al. Knockdown of sodium channel NaV1.6 blocks mechanical pain and abnormal bursting activity of afferent neurons in inflamed sensory ganglia. Pain. 2013;154(8):1170–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren YS, Qian NS, Tang Y, et al. Sodium channel Nav1.6 is up-regulated in the dorsal root ganglia in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Brain Res Bull. 2012;87(2–3):244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jamieson SM, Liu J, Connor B, et al. Oxaliplatin causes selective atrophy of a subpopulation of dorsal root ganglion neurons without inducing cell loss. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56(4):391–399. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0953-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ta LE, Espeset L, Podratz J, et al. Neurotoxicity of oxaliplatin and cisplatin for dorsal root ganglion neurons correlates with platinum-DNA binding. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27(6):992–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott RH, Manikon MI, Andrews PL. Actions of cisplatin on the electrophysiological properties of cultured dorsal root ganglion neurones from neonatal rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1994;349(3):287–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00169295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Renn CL, Carozzi VA, Rhee P, et al. Multimodal assessment of painful peripheral neuropathy induced by chronic oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in mice. Mol Pain. 2011 doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-7-29. 7(29) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tredici G, Tredici S, Fabbrica D, et al. Experimental cisplatin neuronopathy in rats and the effect of retinoic acid administration. J Neurooncol. 1998;36(1):31–40. doi: 10.1023/a:1005756023082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sittl R, Carr RW, Fleckenstein J, et al. Enhancement of axonal potassium conductance reduces nerve hyperexcitability in an in vitro model of oxaliplatin-induced acute neuropathy. Neurotoxicology. 2010;31(6):694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grunze H, von Wegerer J, Greene RW, et al. Modulation of calcium and potassium currents by lamotrigine. Neuropsychobiology. 1998;38(3):131–138. doi: 10.1159/000026528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pisciotta M, Prestipino G. Anticonvulsant phenytoin affects voltage-gated potassium currents in cerebellar granule cells. Brain Res. 2002;941(1–2):53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02563-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wickenden AD, Yu W, Zou A, et al. Retigabine, a novel anti-convulsant, enhances activation of KCNQ2/Q3 potassium channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58(3):591–600. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burgess DL, Kohrman DC, Galt J, et al. Mutation of a new sodium channel gene, Scn8a, in the mouse mutant ‘motor endplate disease. Nat Genet. 1995;10(4):461–465. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Craner MJ, Hains BC, Lo AC, et al. Co-localization of sodium channel Nav1.6 and the sodium-calcium exchanger at sites of axonal injury in the spinal cord in EAE. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 2):294–303. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stys PK, Waxman SG, Ransom BR. Ionic mechanisms of anoxic injury in mammalian CNS white matter: role of Na+ channels and Na(+)-Ca2+ exchanger. J Neurosci. 1992;12(2):430–439. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00430.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu XT, Dai ZH, Xu Q, et al. Safety and efficacy of calcium and magnesium infusions in the chemoprevention of oxaliplatin-induced sensory neuropathy in gastrointestinal cancers. J Dig Dis. 2013;14(6):288–298. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wen F, Zhou Y, Wang W, et al. Ca/Mg infusions for the prevention of oxaliplatin-related neurotoxicity in patients with colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(1):171–178. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frankenhaeuser B, Hodgkin AL. The action of calcium on the electrical properties of squid axons. J Physiol. 1957;137(2):218–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]