Abstract

Objectives

Patient and provider preferences toward CT colonography (CTC) remain unclear. The primary goals of this study were 1) to investigate patient preferences for one of the currently recommended CRC screening modalities and 2) to evaluate provider preferences before and after review of updated guidelines.

Methods

Cross-sectional survey of ambulatory-care patients and providers in the primary care setting. Providers were surveyed before and after reviewing the 2008 guidelines by the American Cancer Society, US Multisociety Task Force on Colorectal Cancer and the American College of Radiology.

Results

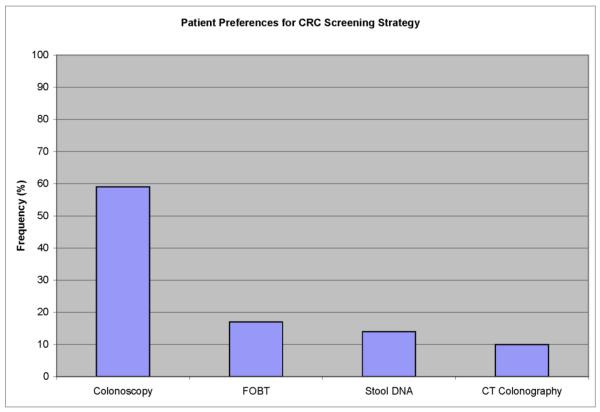

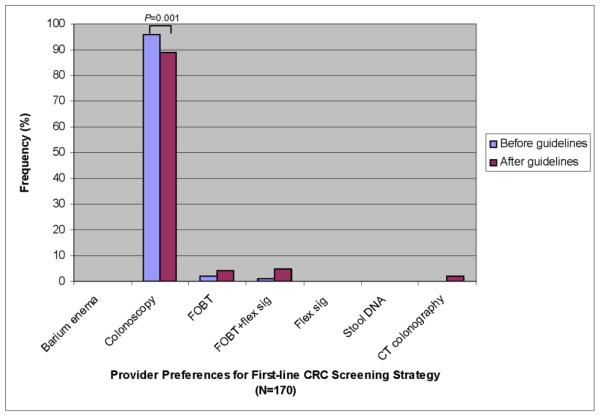

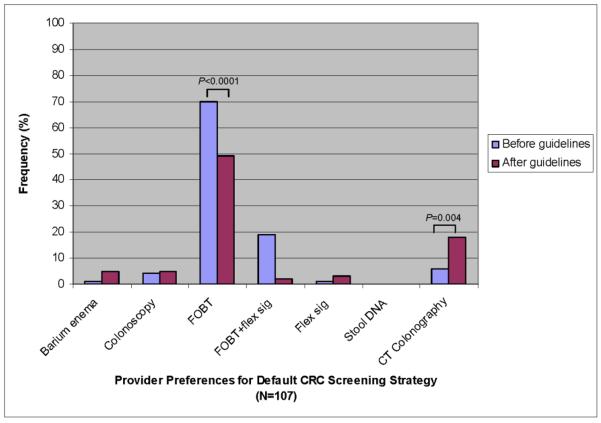

Of 100 patients surveyed, 59% preferred colonoscopy, 17% fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), 14% stool DNA (sDNA) testing, and 10% CTC (P <0.001). The majority of those whose first choice was a stool-based test chose the alternate stool-based test as their second choice over CTC or colonoscopy (P<0.0001). Patients who preferred colonoscopy chose accuracy (76%) and frequency of testing (10%) as the most important test features, whereas patients who preferred a stool-based test chose discomfort (52%) and complications (23%). Of 170 providers surveyed, 96% chose colonoscopy, 2% FOBT, and 1% FOBT with flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) (p < 0.0001). No providers chose CTC or sDNA as their preferred option before reviewing guidelines, and 89% kept their preference after review of guidelines. As a default option for patients who declined colonoscopy, 44% of providers chose FOBT, 12% FOBT+FS, 4% CTC, and 37% deferred to patient preference before review of guidelines. Of the 33% of providers who changed their preference after review of guidelines, 46% recommended CTC. Accuracy was the most influential reason for provider test choice.

Conclusions

Patients and providers prefer colonoscopy for CRC screening. Revised guidelines endorsing the use of CTC are unlikely to change provider preferences but may influence choice of default strategies for patients who decline colonoscopy.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related death and the third most commonly diagnosed cancer among men and women in the United States. [1, 2] Screening has been shown to be a cost-effective strategy for reducing both CRC mortality through early detection and CRC incidence through the detection and removal of precancerous adenomatous polyps. Despite its efficacy and widespread endorsement by authoritative groups, [3–5] screening rates among both average- and high- risk groups remain suboptimal [6–10].

Although most providers prefer colonoscopy because of its superior adenoma detection rates, [11, 12] up to 40% of patients choose stool-based testing after learning about the advantages and disadvantages of the various screening tests. [13] The availability of multiple screening modalities with different pros and cons and the lack of consensus regarding the single most cost-effective strategy have led most authoritative groups to advocate a shared decision-making (SDM) approach when selecting a screening strategy. [14–16] SDM is a sequential, interactive process involving information exchange, values clarification, decision-making and mutual agreement. [17]

Inherent in this approach is the need to elicit not only patient but also provider preferences for one of the recommended screening options, since physician recommendation has been shown to be a major determinant of CRC screening uptake among patients. [18–20]

Computed tomography colonography (CTC) and stool-based DNA testing (sDNA) are newer screening modalities that were recently endorsed in guidelines proposed by the joint American Cancer Society (ACS), GI Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer (GI-MSTF) and the American College of Radiology (ACR). [15] Neither CTC nor sDNA, however, were included in revised guidelines proposed by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which concluded that there was insufficient evidence to warrant an endorsement. The extent to which the new ACS/GI-MSTF/ACR guidelines will impact provider recommendations or patient acceptance of CTC within the context of SDM is unclear.

We conducted separate surveys of patients and providers to investigate preferences for CRC screening. The primary goals of this study were 1) to investigate patient preferences for one of the currently recommended CRC screening modalities using a decision aid in the primary care setting and 2) to evaluate provider preferences before and after review of updated CRC screening guidelines.

Methods

We surveyed both patients and providers. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Boston Medical Center (BMC).

Patient Survey

Study Population

Asymptomatic patients aged 50–75 without prior endoscopic or radiologic CRC screening who had an upcoming appointment with their primary care provider (PCP) were eligible. Patients unable to speak or read English were excluded. Patients with a personal history of colonic neoplasia, inflammatory bowel disease or family history of colorectal neoplasia were also excluded. Subjects were recruited from two internal medicine resident primary care ambulatory clinics at BMC. Eligible subjects were identified prior to their PCP visit and permission to contact the patient was obtained from the PCP. Subjects who completed the interview were compensated for their time with a $15 gift card.

Study Design

We employed a cross-sectional survey design similar to that used in our prior studies on patient preferences for CRC screening. [13, 21] Written consent was obtained prior to initiating the survey. The survey was conducted in a private consultation room in the ambulatory care clinic using a structured interviewer format in which one of two research staff verbally read the educational components of the instrument to the subject who followed along visually. Subjects were encouraged to ask questions.

At the end of each section, staff assessed knowledge and if questions were answered incorrectly, the relevant material was reviewed until the subject could answer the questions correctly. After the educational component, subjects identified a screening preference and test features influencing their choice. The entire interview took approximately 30 minutes.

Survey Instrument

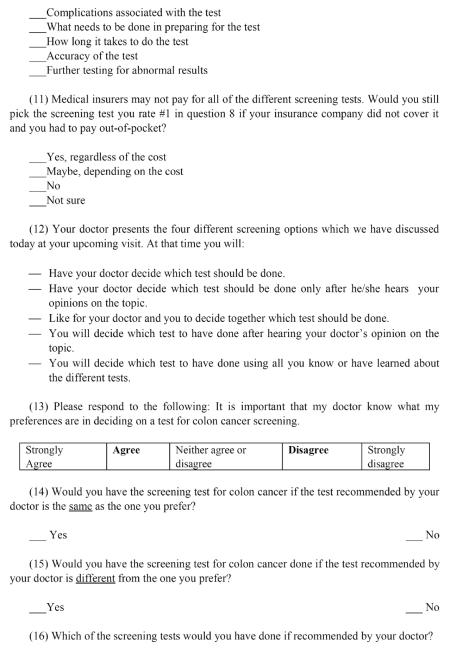

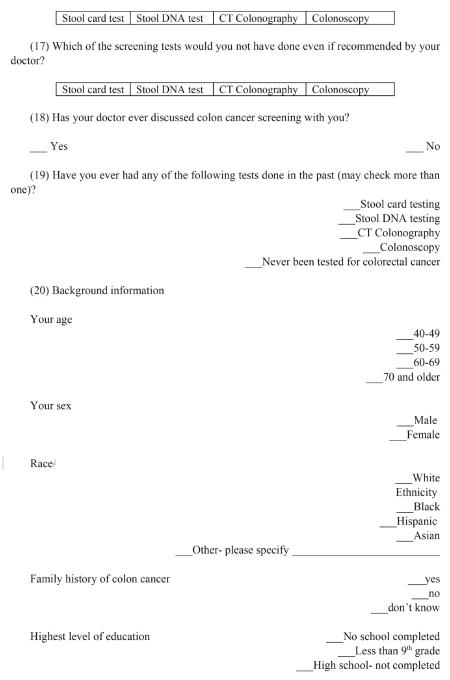

Our survey was composed of 3 main parts: (1) decision aid, (2) assessment of patient preferences and factors influencing choices, and (3) demographic information. A complete survey is attached in Appendix 1.

Decision Aid. Apart from information about CTC, the decision aid was very similar in content and format to previously validated tools. [13, 21] It was comprised of a series of segments that provided a brief overview of the rationale for CRC screening, descriptions of the four relevant screening tests, comparisons between the different tests with respect to individual test features, and a summary of the different test features for each screening strategy.

Patient preferences. Subjects were asked to rank order preferences for screening modality and features influencing their choice. They were also asked about desire to participate in decision making process, and willingness to pay if preference was not covered by insurance.

Demographic information. Age, sex, ethnicity, race, education, insurance coverage, prior FOBT testing, and reasons for lack of prior screening were obtained.

Sample Size and Power Calculation

Our analyses focused on patient screening preferences and identification of patient characteristics and attitudes associated with screening preferences. Existing data suggests that 50–60% of patients prefer colonoscopy [21] and 25–45% prefer stool based tests. [13] Data on patient preferences for CTC were unknown at the time. We determined that a sample of 200 subjects would provide >80% power of detecting a 20% difference in preference between colonoscopy and CTC and 98% power of detecting a 25% difference in preference between CTC and stool-based tests at the two-tailed P <0.05 level.

An interim analysis was performed after recruitment of 100 patients. Based on the results of these first 100 patients and assuming that observed trends reflected the true differences between test preferences, we calculated the conditional power for observing significant pairwise differences in preferences for FOBT, sDNA, and CTC given an additional 100 patients (total n=200). [22] Each of these strategies was preferred by a minority of patients compared to colonoscopy (59%). If the 100 additional patients were recruited, the study would have less than 10% power of showing a difference between FOBT and either sDNA or CTC, and less than 30% power of showing a difference between sDNA or CTC. This projection suggested that further enrollment was unlikely to demonstrate a significance difference between FOBT, sDNA and CTC. Hence, enrollment was stopped at n=100 patients.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to characterize the study population, screening preferences and important test features associated with preferences. The percentages of patients preferring each screening option were compared using chi-square goodness-of-fit test for equal percentages. Chi-square tests of independence were used to assess associations between outcome variables and demographic factors including age (50–59, ≥60), sex, ethnicity, race (white, black, other), education (high school degree or less, some college and above), insurance status (private, Medicare, Medicaid, Freecare, none), and prior FOBT testing (yes, no). Similar analyses were used to evaluate associations between decision making autonomy, role of insurance coverage and patient characteristics. Significance was defined at the P <0.05 level. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Provider Survey

Study Population and Design

Surveys were randomly distributed to a convenience sample of general internal medicine and family medicine residents, physicians, physician assistants and nurse practitioners working in the outpatient primary care clinics at Boston Medical Center and its 5-affiliate community health centers (Codman Square, Dorchester House, East Boston Neighborhood, South Boston, South End). The survey took approximately 10 minutes. Obtainment of informed consent had been waived by the IRB at BMC.

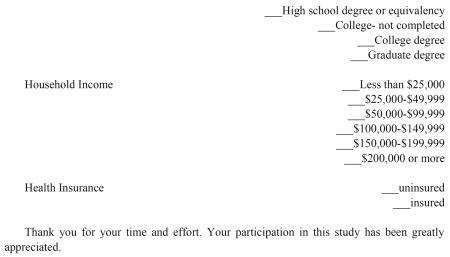

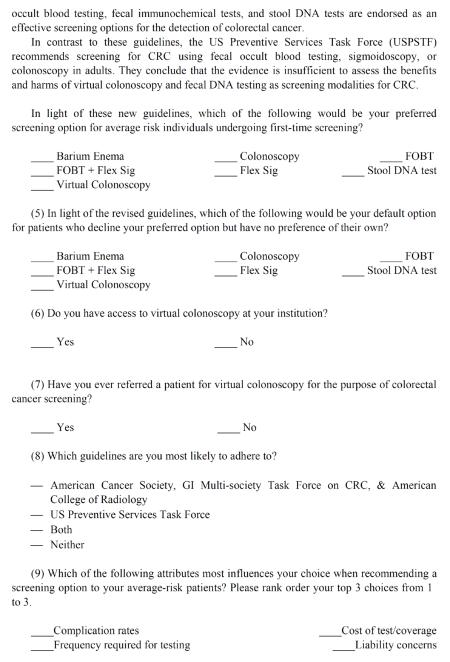

Survey Instrument

A 19-item close-ended questionnaire was developed to assess provider screening test preferences among recommended options (CTC, colonoscopy, sDNA, and FOBT with flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS)) as well as non-recommended options (barium enema, FOBT, FS alone) before and after reviewing recent guidelines on CRC cancer screening by the ACS/GI-MSTF/ACR and USPSTF (Appendix 2). Providers were also asked about factors influencing their preferences, the guidelines to which they adhere, and demographic information.

Sample Size and Power Calculations

A sample size estimate of 200 was determined based on the number of practitioners who met eligibility requirements at participating sites.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to characterize the practitioners, their preferences, and influencing factors. Chi-square analysis was used to compare associations between outcome variables and provider factors. McNemar's test for paired categorical data was used to evaluate change in provider preferences before and after reviewing guidelines. For our analysis of change in default screening option before and after reviewing guidelines, those who selected “defer to patient preference” were excluded.

Results

Patient Survey

Sample Characteristics

A total of 121 subjects were consecutively enrolled between October 2008 and February 2010 of which 100 met eligibility criteria and agreed to participate. Of the excluded subjects, six had already had CRC screening not documented in our records, 10 refused due to time constraints, and 5 had immediate competing medical issues. Table 1 summarizes the sample demographics. The patients were predominantly aged 50–59, black, with high school education or less, and Medicaid or free care insurance.

Table 1.

Description of patient population (N=100)

| Characteristic | Number |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age, years | |

| 50–59 | 75 |

| 60–69 | 24 |

| 70+ | 1 |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Male | 63 |

| Female | 37 |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 3 |

| Non-Hispanic | 97 |

|

| |

| Race | |

| White | 19 |

| Black | 73 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Other | 4 |

| Missing | 3 |

|

| |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 28 |

| High school degree | 44 |

| Some college | 12 |

| College degree | 9 |

| Graduate degree | 7 |

|

| |

| Health insurance | |

| Private/HMO | 19 |

| Medicare | 7 |

| Medicaid | 36 |

| Free care | 32 |

| None | 6 |

|

| |

| Prior FOBT | 32 |

FOBT = fecal occult blood testing.

HMO = health maintenance organization.

Reasons for not having had prior CRC screening were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, where 0=not important and 5=very important. “I don't need one because I feel fine” was found to be the most important reason with a mean score (standard deviation) of 1.8 ± 1.6, followed by “The test(s) are painful,” (1.7 ± 1.6), “No one in my family has/had colorectal cancer,” (1.7 ± 1.6), “My doctor never recommended screening,” (1.7 ± 1.7), “I might get injured by the testing,” (1.6 ± 1.7), “The test(s) are too embarrassing,” (0.9 ± 1.3), “I'm not sure I want to know if I have cancer,” (0.9 ± 1.5), “I am worried that the doctor might find that I have colorectal cancer” (0.8 ± 1.2), “I don't want to use an enema or laxative,” (0.8 ± 1.3), and “I don't want to handle my stool” (0.4 ± 0.98).

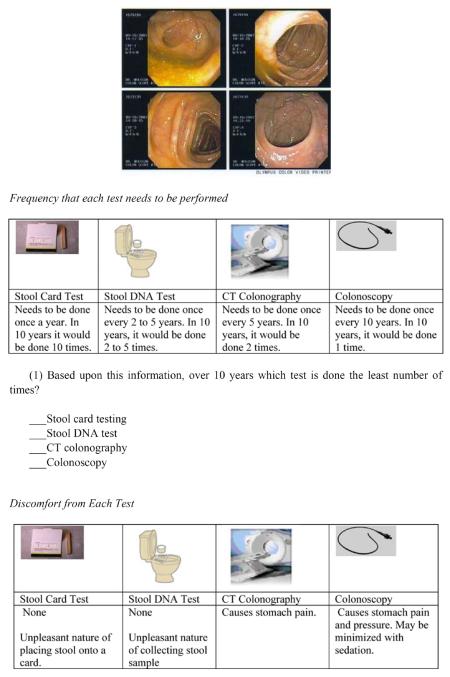

Screening Test Preference and Features Influencing Choice

Overall, patients were significantly (P <0.001) more likely to chose colonoscopy (59%) than FOBT (17%), sDNA (14%) and CTC (10%); the differences between the other screening tests were non-significant (Figure 1). Eight-seven percent (27 of 31) of those whose first choice was a stool-based test chose the alternate stool-based test over CTC or colonoscopy (P<0.0001) and 13% (4 of 31) chose either CTC or colonoscopy. Moreover, of those who preferred stool-based testing, 68% (21 of 31) preferred CTC over colonoscopy as their next choice (P=0.07).

Figure 1.

Patient preferences for CRC screening strategy.

Table 2 shows the association between test feature and screening preferences. Combined data for the two stool-based tests is shown because results were similar when FOBT and sDNA were analyzed separately. Patients who preferred colonoscopy chose accuracy (76%) followed by frequency of testing (10%) as the most important test features influencing their choice. Conversely, those who preferred one of the stool-based tests were more concerned about discomfort (52%), followed by complications (23%). Patients who preferred CTC were more likely to choose accuracy (40% vs. 13%) than those who preferred one of the stool-based tests, but also more likely to choose concerns about discomfort (20%).

Table 2.

Test features influencing screening test preference

| Preference, N (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Most important test feature | Any stool test* N =31 | CTC N=10 | Colonoscopy N= 59 |

| Accuracy | 4 (13) | 4 (40) | 45 (76) |

| Discomfort | 16 (52) | 2 (20) | 1 (2) |

| Preparation | 4 (13) | 0 | 0 |

| Complications | 7 (23) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Time | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 (2) |

| Frequency of test | 0 | 0 | 6 (10) |

| Further testing for abnormal results | 0 | 3 (30) | 5 (8) |

Any stool test = fecal occult blood testing or stool DNA

Overall comparison significant at P<0.0001 level.

CTC = CT colonography

Subgroup comparisons were performed to assess whether screening preferences varied by demographic factors or prior FOBT (Table 3). Sex and education were associated with test preference. Compared to men, women more frequently (P=0.04) preferred colonoscopy (70 vs. 52%) and CTC (14 vs. 8%).

Table 3.

Univariate associations between demographic factors and screening test preference

| Preference, N(%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Characteristic | No. | FOBT | Stool DNA testing | CTC | Colonoscopy | P* |

|

| ||||||

| Age, years | 0.69 | |||||

| 50–59 | 75 | 15 (20) | 10 (13) | 7 (9) | 43 (57) | |

| ≥ 60 | 25 | 2 (8) | 4 (16) | 3 (12) | 16 (64) | |

|

| ||||||

| Sex | 0.04 | |||||

| Male | 63 | 13 (21) | 12 (19) | 5 (8) | 33 (52) | |

| Female | 37 | 4 (11) | 2 (5) | 5 (14) | 26 (70) | |

|

| ||||||

| Ethnicity | 0.17 | |||||

| Hispanic | 3 | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 97 | 15 (15) | 14 (14) | 10 (10) | 58 (60) | |

|

| ||||||

| Race | 0.42 | |||||

| White | 19 | 4 (21) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 14 (74) | |

| Black | 73 | 9 (12) | 13 (18) | 10 (14) | 41 (56) | |

| Other | 5 | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (60) | |

|

| ||||||

| Education | 0.003 | |||||

| ≤ High school degree | 72 | 17 (24) | 11 (15) | 9 (13) | 35 (49) | |

| Some college or more | 28 | 0 (0) | 3 (11) | 1 (4) | 24 (86) | |

|

| ||||||

| Health insurance | 0.19 | |||||

| Private/HMO | 19 | 2 (11) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 16 (84) | |

| Medicare | 7 | 3 (43) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 3 (43) | |

| Medicaid | 36 | 6 (17) | 5 (14) | 4 (11) | 21 (58) | |

| Free care | 32 | 6 (19) | 4 (13) | 5 (16) | 17 (53) | |

| None | 6 | 0 (0) | 3 (50) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | |

|

| ||||||

| Prior FOBT | 0.28 | |||||

| Yes | 32 | 3 (9) | 7 (22) | 1 (3) | 21 (66) | |

| No | 68 | 14 (21) | 7 (10) | 9 (13) | 38 (56) | |

Comparison for any stool test (blood or DNA) vs. CTC vs. colonoscopy.

CTC = CT colonography.

FOBT = fecal occult blood test.

HMO = health maintenance organization.

Compared to those with a high school degree or less education, those with some college or more frequently (P=0.003) preferred colonoscopy (86 vs. 49%). Those with a high school degree or less choose CTC more often than those with higher education (13 vs. 4%, P=0.17). Though not significant, all of those who chose CTC were black (n=10). Age, ethnicity, race, insurance, and prior FOBT were not associated with test preference.

Impact of Insurance Coverage

When asked if they would still pick their first choice screening test if it was not covered by their insurance company and they had to pay out-of-pocket, 24% said yes regardless of the cost, 25% said maybe depending on the cost, 29% said no, and 22% were not sure. Subjects who preferred stool based tests were more likely to respond “no” in their willingness to pay out of pocket compared to colonoscopy or CTC (42 vs. 25 vs. 10%, P=0.01). Age, sex, race, education, insurance, prior FOBT and most influential test feature were not associated with willingness to pay.

Decision Making Autonomy

When asked about who should decide what test to pursue, 53% said the doctor and patient equally, 20% said the patient alone, 13% said the doctor alone, 7% each said mostly the patient and mostly the doctor. Compared with subjects with high school degree or above, those with less than high school education were more likely to favor a doctor-dominant (doctor alone or mostly the doctor) or shared process (96% vs. 64%, P <0.0001). This trend also occurred when education was compared dichotomously at high school education or below versus above high school (P=0.06).

Decision making autonomy did not vary by age, sex, race, insurance, prior FOBT or first choice test. When asked whether it is important that the doctor know their preferences for CRC screening test, 95% either agreed (n=36) or strongly agreed (n=58) and 5% were neutral.

When asked if they would complete a CRC screening test if the test recommended by their doctor was the same as the one they prefer, 96% said yes, 1% said no and 3% were not sure. When asked if they would complete a CRC screening test if the test recommended by their doctor was different from the one they prefer, 49% said yes, 21% said no and 30% were not sure. There was no association between response choice and demographic variables.

Provider Survey

Sample Characteristics and CRC Screening Preferences

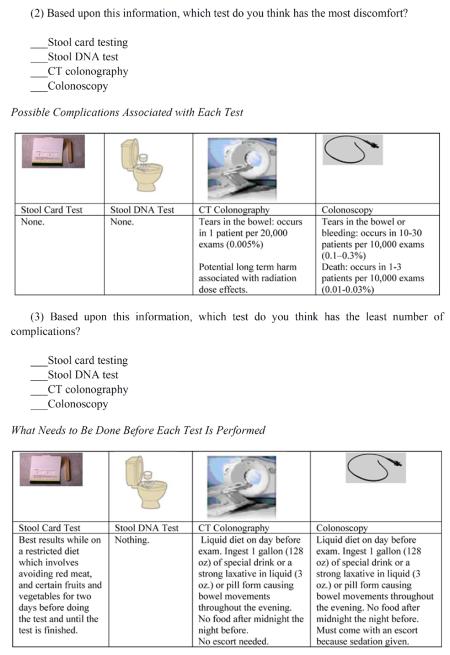

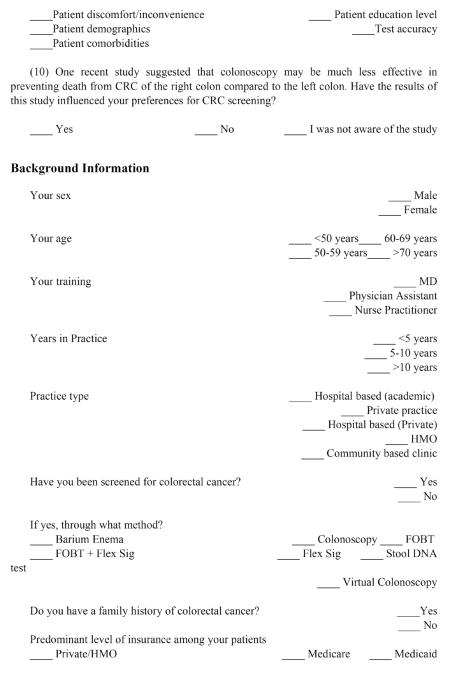

A total of 170 providers completed the survey between January and June 2009. Table 4 lists their characteristics. Overall, 96% of providers chose colonoscopy, 2% FOBT, and 1% FOBT with flex sig as their preferred option before reviewing guidelines No providers selected CTC, barium enema, flex sig alone or stool DNA. After review of guidelines, 89% of providers kept their initial screening preference, with the majority (99%) still preferring colonoscopy (Figure 2). Of the 11% who changed their first-line screening test after reviewing guidelines, 42% now preferred FOBT+FS, 32% FOBT, 21% CTC, and 5% colonoscopy.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the provider sample

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Provider type | |

| Medical doctor | |

| Resident | 88 (52) |

| Non-resident | 68 (40) |

| Physician assistant | 4 (2) |

| Nurse practitioner | 10 (6) |

|

| |

| Male | 75 (45) |

|

| |

| Practice experience, years | |

| <5 | 110 (65) |

| 5–10 | 16 (9) |

| >10 | 44 (26) |

|

| |

| Practice setting | |

| Hospital based | 119 (70) |

| Community-based clinic | 51 (30) |

|

| |

| Personal experience with CRC screening | 25 (14) |

|

| |

| Predominant level of insurance | |

| Private | 4 (2) |

| Medicare | 21 (12) |

| Medicaid | 59 (35) |

| VA | 6 (4) |

| Free care | 71 (42) |

| None | 1 (1) |

| Don't know | 8 (5) |

CRC = colorectal cancer.

Figure 2.

Comparison of first-line CRC screening strategy preferred by providers before and after review of guidelines.

There was a significant decrease in colonoscopy as the first-line screening choice before and after guidelines (96 vs. 89%, P=0.001).

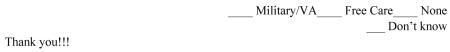

When asked to identify a default option for patients who declined colonoscopy, 44% of providers chose FOBT, 12% FOBT+FS, 4% CTC, and 37% deferred to patient preference before review of guidelines.

Among the 107 providers who did not defer to patient preference, 67% kept their default screening preference after review of guidelines with the majority (69%) still favoring FOBT alone (Figure 3); of the 33% of providers who changed, 46% now recommended CTC, 23% FOBT+FS, 11% barium enema, 9% FOBT, 6% colonoscopy, and 6% FS. Both the increase in CTC (6 vs. 18%, P=0.004) and decrease in FOBT (70 vs. 49%, P<0.0001) were significant.

Figure 3.

Comparison of default CRC screening strategy preferred by providers before and after review of guidelines.

Choice of default screening method differed by level of training (P=0.03). Compared with attendings, residents were more likely to recommend FOBT+FS (17 vs. 6%) or comply with patient preference (42 vs. 32%) and less likely to recommend FOBT alone (35 vs. 54%). Both residents and attendings were equally likely to recommend CTC (3 vs. 4%).

Gender was associated with default test recommendation such that female practitioners were more likely to recommend CTC (25 v. 19%) and less likely to recommend FOBT alone (29 vs. 45%) compared to males (P=0.05). In terms of practice type, hospital-based practitioners were less likely to recommend FOBT testing (37 vs. 61%) and more likely to defer to patient preference (46 vs. 26%) than community based practitioners (P=0.02). After review of guidelines, academic practitioners were less likely to recommend FOBT testing (30 vs. 52%) and more likely to recommend CTC (27 vs. 12%) than community based practitioners (P=0.04). Number of years in practice, personal CRC screening experiences, and predominant practice insurance type were not associated with screening recommendations in any scenario.

Access to CTC

Of the 143 providers who answered, 54% had access to CTC and 46% did not. Of the 170 providers who answered, only 11% said they had ever referred a patient for CTC. Before guidelines, more providers with access to CTC would recommend it as a default screening option (6 vs. 0%, P=0.02). Choice of first line and default screening test after review of guidelines did not differ by access to CTC.

Guidelines

When asked to which guidelines they were most likely to adhere, 43% of providers choose USPSTF, 25% ACS/GI-MSTF/ACR, 31% both and 1% neither.

Reason for Test Recommendation

Providers strongly valued accuracy in their recommendation of test choice with 67% listing this as the most influential reason compared to 8% who listed frequency of testing, 8% patient discomfort, 7% patient comorbidities, 5% complication rates, 2% cost of test, 2% liability, 1% patient demographics and 1% educational level (P<0.0001). Since providers overwhelmingly choose colonoscopy as their preferred screening method, analysis between association between most influential reason and primary test was not performed.

Conclusion

In this study of 100 primary care patients using a decision-aid tool explaining CRC screening options, we confirmed that patients have distinct preferences for one of several available CRC screening tests and that their choice reflects the relative value they place on test features. The majority of patients preferred colonoscopy followed by stool-based testing. Among those who preferred colonoscopy, accuracy was the most important test feature whereas among those who preferred stool-based testing, discomfort was the most important test feature, which is consistent with prior studies. [11, 13] Relatively few patients selected CTC as their preferred test; however, among patients who preferred stool-based tests, CTC was preferred over colonoscopy as a default screening option. Women and those with higher education preferred colonoscopy. We also found that a majority of patients want to play an active role in decision making, although those with less education wanted more provider input.

Understanding the available CRC screening options, weighing their attributes, and ultimately selecting the test that is most aligned with individual preferences can be a time-consuming and challenging process for patients and practitioners alike. Different methods have been used previously in the research setting to help with CRC screening decisions. Explicit techniques ask patients to compare the relative importance of relevant characteristics of a decision and include rating and ranking, [23] maximal differential scaling, [24] and conjoint analysis (aka choice-format or discrete choice experiments). [11, 23, 25] In rating and ranking, patients rate on a Likert scale the importance of different decision attributes, whereas in maximal differential scaling, respondents make choices among a series of sets of items from master list in lieu of rating. In conjoint analysis, which has been used in marketing, economics and psychology, [26] multiple sets of two hypothetical options with different attributes are presented to the patient who must pick their preferred options or state they have no preferences. In all of these approaches, the results can be used to help the patient select the test which is most congruous with their answers. In this study, we used a more direct technique, in which patients received detailed information about choices and considered their potential value on their own. This approach has been used previously in CRC screening decision aids [13, 27] and has the benefit of providing more thorough information on test choices as part of an informed decision making process. It also is intuitively more practical for clinical use.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to elicit patient preferences for CTC among the menu of other recommended modalities in asymptomatic patients who were previously unscreened. A survey of 68 patients previously non-adherent with recommendations for CRC screening found that 80% were willing to undergo CTC but 70% would not be willing to pay. [28] This study was limited by a lack of a comparison modality and in its generalizability given the homogeneity of the population, which was mostly white. Studies among patients who have been previously screened are conflicting and highlight potential racial differences in preferences. A survey of 205 ethnically diverse patients found no significant difference in ratings for colonoscopy, CTC, or fecal immunochemical testing (FIT). [11] However, blacks were more likely to prefer FS and colonoscopy, which was not fully explained by elicited values. They also found that the less educated were less likely to prefer colonoscopy and choose FOBT, consistent with our findings. A convenience sample of 323 patients at a video rental store found that after hearing about test choices, 60% preferred CTC because it is noninvasive and does not require sedation compared to 26% colonoscopy. [29] Those with higher income preferred CTC. Of note, only 20% of respondents were aged ≥ 50. A theoretical choice format survey of 547 Canadians found that test accuracy followed by test process were valued highly, however based on overall attributes, CTC would be preferred over colonoscopy because it is non-ninvasive. [25] Thirty percent of respondents preferred no screening. In contrast, a survey of 92 Veterans using a computer based decision aid to compare FOBT, FS, colonoscopy, CTC, and colon capsule endoscopy found that 62% prefer colonoscopy, 23% capsule, and 10% CTC. [24] The study must be interpreted with caution as 85% of these patients had prior screening of which 78% had had colonoscopy.

Preferences for CTC and colonoscopy among patients who have experienced both remain mixed, [29–31] with some studies favoring CTC [32–36] and others favoring colonoscopy. [37–40] A study of ethnically diverse patients found that racial and ethnic minorities were less likely than whites to prefer CTC over colonoscopy (66% white, 45% black, 36% Hispanic). [39] Overall, minorities were less satisfied with CTC and less willing to undergo it again. In our study, although not statistically significant, all patients who preferred CTC were black. Our new findings highlight that while CTC may not be preferred to colonoscopy, it may have a role as a default screening strategy in patients who prefer stool blood testing.

In our survey of 170 primary care providers, we found that providers overwhelmingly value accuracy and promote colonoscopy as their first choice screening test and did not change after review of new ACS/GI-MSTF/ACR guidelines. After review of guidelines, however, providers were more like to consider CTC as a default screening strategy for patients who decline colonoscopy though they still preferred FOBT for this group. There were some differences by level of training, gender, and practice setting. In a different web-based survey designed to assess knowledge of CTC, only 12% of providers were aware of CRC screening guidelines including CTC. [41] While our study explicitly reviewed guidelines that included CTC, we still found that provider behavior is unlikely to change despite new guidelines. Our findings are consistent with existing literature on the secular trends of providers preferring colonoscopy and valuing accuracy most. [13, 21, 27, 29] Interestingly, previous work suggests that while providers and patients both value accuracy highly, providers perceive that patients may value discomfort the most, which may influence their discussion. [21] Most providers seem to have a preferred option and one default option and do not routinely discuss entire menu of screening options, [42, 43] which our current work supports given how patients dichotomize into those who value accuracy and those that value discomfort.

While our study's main strengths are its inclusion of CTC among the CRC screening options as well as the participation of both patients and providers, we acknowledge certain limitations. First, we did not evaluate CTC with non-cathartic bowel preparation, which may increase the appeal of CTC and change patient preferences.

A previous survey of 212 patients showed that preparation was a low attribute in test selection; [11] however, another survey conducted in Australia among patients with symptoms suspicious for CRC found that while colonoscopy was preferred to CTC, as the need for second procedure and accuracy increased and cost of CTC rose, CTC would be preferred to colonoscopy if no bowel preparation was needed.[44]

In a recent randomized control trial of over 8000 patients evaluating participation and yield of colonoscopy versus non-cathartic CTC in the Netherlands, Stoop et al. found that when no bowel preparation is needed, patients are more likely to adhere to CTC (34%) than colonoscopy (22%). [45] Colonoscopy, however, yielded more adenomas. We did not discuss other subtleties with CTC such as discovery of incidental findings, which may have changed responses but was outside the scope of this study.

Our study did not include newer FIT and therefore, we can not draw conclusions, although there is some evidence that FIT may be better accepted than FS or colonoscopy. [46, 47] In a study of ethnically diverse patients using conjoint analysis, both FIT and CTC were preferred over older tests such as FS and FOBT, though colonoscopy was still the most preferred [11].

Those who ranked discomfort and accuracy highly tended to prefer FIT, compared with those who ranked accuracy and test frequency highly who tended to prefer CTC. A recent large randomized controlled trial of FIT versus colonoscopy in Spain showed greater adherence with biannual FIT (34%) compared to colonoscopy (25%). [48]

We did not include specific information on cost in our decision aid, which may impact choices; however, the extent to which cost considerations influence patient preferences is unclear. Two studies found that cost was not a significant determinant of patient preferences for CRC screening strategy, [49, 50] whereas one study comparing FOBT and FS found that patient preferences were sensitive to out-of-pocket expenses. [51]

We did ask patients about their willingness to pay for their preferred screening test if not covered by insurance, but in the absence of cost information, conclusions can not be drawn. Another limitation is that our study does not address whether or not eliciting patient and provider preferences changes behavior, such as type of screening test ordered, adherence or other outcomes.

There is some evidence to suggest that despite the use of decision aids, such as ours, the overall effectiveness depends on the extent to which providers comply with patient preferences. [52] Lastly, despite the racially diversity in our sample, our findings may have limited generalizability beyond an urban, socioeconomically disadvantaged referral center.

In summary, our study finds that both primary care providers and patients prefer colonoscopy and that recent guidelines endorsing CTC as a screening option are unlikely to change provider preferences. Still, CTC may have a role as a default strategy in those who decline colonoscopy.

Our work contributes to the growing body of literature regarding the importance of employing a shared decision-making approach when selecting an appropriate screening strategy.

Future studies are needed to determine whether the elicitation of patient preferences within the context of shared-decision making improve CRC screening participation.

Abbreviations

- ACR

American College of Radiology

- ACS

American Cancer Society

- BMC

Boston Medical Center

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CTC

computed tomography colonography

- FOBT

fecal occult blood testing

- FIT

fecal immunochemical testing

- FS

flexible sigmoidoscopy

- GI-MSTF

GI Multi-Society Task Force

- HMO

health maintenance organization

- PCP

primary care provider

- sDNA

stool DNA

- SDM

shared decision making

- USPSTF

United States Preventive Services Task Force

APPENDIX A

APPENDIX B

References

- [1].Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ries LA, Wingo PA, Miller DS, et al. The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973-1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2000;88:2398–424. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000515)88:10<2398::aid-cncr26>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;149:627–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2008;58:130–60. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rex DK, Johnson DA, Anderson JC, Schoenfeld PS, Burke CA, Inadomi JM. American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for colorectal cancer screening 2009 [corrected] Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:739–50. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Klabunde CN, Cronin KA, Breen N, Waldron WR, Ambs AH, Nadel MR. Trends in colorectal cancer test use among vulnerable populations in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1611–21. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mitka M. Colorectal cancer screening rates still fall far short of recommended levels. JAMA. 2008;299:622. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.6.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rim SH, Joseph DA, Steele CB, Thompson TD, Seeff LC. Colorectal cancer screening - United States, 2002, 2004, 2006, and 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(Suppl):42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:389–94. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, Saslow D, Shah M, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2011: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011;61:8–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hawley ST, Volk RJ, Krishnamurthy P, Jibaja-Weiss M, Vernon SW, Kneuper S. Preferences for colorectal cancer screening among racially/ethnically diverse primary care patients. Med. Care. 2008;46:S10–6. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d932e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Marbet UA, Bauerfeind P, Brunner J, Dorta G, Valloton JJ, Delco F. Colonoscopy is the preferred colorectal cancer screening method in a population-based program. Endoscopy. 2008;40:650–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1077350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Schroy PC, 3rd, Lal S, Glick JT, Robinson PA, Zamor P, Heeren TC. Patient preferences for colorectal cancer screening: how does stool DNA testing fare? Am. J. Manag. Care. 2007;13:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Whitlock E, Lin J, Liles E, Beil T, Fu R. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):638–658. W117–W122. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Hopkins RH, Jr, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Guidance Statement From the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:378–86. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:780–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Brawarsky P, Brooks DR, Mucci LA, Wood PA. Effect of physician recommendation and patient adherence on rates of colorectal cancer testing. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2004;28:260–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Janz NK, Wren PA, Schottenfeld D, Guire KE. Colorectal cancer screening attitudes and behavior: a population-based study. Prev. Med. 2003;37:627–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012;172:575–82. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ling BS, Moskowitz MA, Wachs D, Pearson B, Schroy PC. Attitudes toward colorectal cancer screening tests. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16:822–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.10337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Andersen PK. Conditional power calculations as an aid in the decision whether to continue a clinical trial. Control Clin. Trials. 1987;8:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(87)90027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pignone MP, Brenner AT, Hawley S, et al. Conjoint analysis versus rating and ranking for values elicitation and clarification in colorectal cancer screening. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012;27:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1837-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Imaeda A, Bender D, Fraenkel L. What is most important to patients when deciding about colorectal screening? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010;25:688–93. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1318-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Marshall DA, Johnson FR, Phillips KA, Marshall JK, Thabane L, Kulin NA. Measuring patient preferences for colorectal cancer screening using a choice-format survey. Value Health. 2007;10:415–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ryan M, Gerard K. Using discrete choice experiments to value health care programmes: current practice and future research reflections. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy. 2003;2:55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shokar NK, Carlson CA, Weller SC. Informed decision making changes test preferences for colorectal cancer screening in a diverse population. Ann. Fam. Med. 2010;8:141–50. doi: 10.1370/afm.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ho W, Broughton DE, Donelan K, Gazelle GS, Hur C. Analysis of barriers to and patients' preferences for CT colonography for colorectal cancer screening in a nonadherent urban population. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010;195:393–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Angtuaco TL, Banaad-Omiotek GD, Howden CW. Differing attitudes toward virtual and conventional colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening: surveys among primary care physicians and potential patients. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001;96:887–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nicholson FB, Barro JL, Bartram CI, et al. The role of CT colonography in colorectal cancer screening. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2315–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cotton PB, Durkalski VL, Pineau BC, et al. Computed tomographic colonography (virtual colonoscopy): a multicenter comparison with standard colonoscopy for detection of colorectal neoplasia. JAMA. 2004;291:1713–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gluecker TM, Johnson CD, Harmsen WS, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with CT colonography, colonoscopy, and double-contrast barium enema examination: prospective assessment of patient perceptions and preferences. Radiology. 2003;227:378–84. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272020293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jensch S, Bipat S, Peringa J, et al. CT colonography with limited bowel preparation: prospective assessment of patient experience and preference in comparison to optical colonoscopy with cathartic bowel preparation. Eur. Radiol. 2010;20:146–56. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1517-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Juchems MS, Ehmann J, Brambs HJ, Aschoff AJ. A retrospective evaluation of patient acceptance of computed tomography colonography (“virtual colonoscopy”) in comparison with conventional colonoscopy in an average risk screening population. Acta. Radiol. 2005;46:664–70. doi: 10.1080/02841850500216277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ristvedt SL, McFarland EG, Weinstock LB, Thyssen EP. Patient preferences for CT colonography, conventional colonoscopy, and bowel preparation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:578–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].van Gelder RE, Birnie E, Florie J, et al. CT colonography and colonoscopy: assessment of patient preference in a 5-week follow-up study. Radiology. 2004;233:328–37. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2331031208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Akerkar GA, Yee J, Hung R, McQuaid K. Patient experience and preferences toward colon cancer screening: a comparison of virtual colonoscopy and conventional colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001;54:310–5. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.117595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Jung HS, Park DK, Kim MJ, et al. A comparison of patient acceptance and preferences between CT colonography and conventional colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2009;24:43–7. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2009.24.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Rajapaksa RC, Macari M, Bini EJ. Racial/ethnic differences in patient experiences with and preferences for computed tomography colonography and optical colonoscopy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007;5:1306–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Taylor SA, Halligan S, Saunders BP, Bassett P, Vance M, Bartram CI. Acceptance by patients of multidetector CT colonography compared with barium enema examinations, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003;181:913–21. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.4.1810913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chang MS, Shah JP, Amin S, et al. Physician knowledge and appropriate utilization of computed tomographic colonography in colorectal cancer screening. Abdom. Imaging. 2011;36:524–31. doi: 10.1007/s00261-011-9698-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Klabunde CN, Lanier D, Nadel MR, McLeod C, Yuan G, Vernon SW. Colorectal cancer screening by primary care physicians: recommendations and practices, 2006–2007. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009;37:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zapka JM, Klabunde CN, Arora NK, Yuan G, Smith JL, Kobrin SC. Physicians' colorectal cancer screening discussion and recommendation patterns. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:509–21. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Howard K, Salkeld G, Pignone M, et al. Preferences for CT colonography and colonoscopy as diagnostic tests for colorectal cancer: a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2011;14:1146–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Stoop EM, de Haan MC, de Wijkerslooth TR, et al. Participation and yield of colonoscopy versus non-cathartic CT colonography in population-based screening for colorectal cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:55–64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Segnan N, Senore C, Andreoni B, et al. Comparing attendance and detection rate of colonoscopy with sigmoidoscopy and FIT for colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2304–12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hol L, van Leerdam ME, van Ballegooijen M, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: randomised trial comparing guaiac-based and immunochemical faecal occult blood testing and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gut. 2010;59:62–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.177089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Quintero E, Castells A, Bujanda L, et al. Colonoscopy versus fecal immunochemical testing in colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:697–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Leard LE, Savides TJ, Ganiats TG. Patient preferences for colorectal cancer screening. J. Fam. Pract. 1997;45:211–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wolf RL, Basch CE, Brouse CH, Shmukler C, Shea S. Patient preferences and adherence to colorectal cancer screening in an urban population. Am. J. Public Health. 2006;96:809–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Pignone M, Harris R, Kinsinger L. Videotape-based decision aid for colon cancer screening. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000;133:761–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-10-200011210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Schroy PC, 3rd, Emmons K, Peters E, et al. The impact of a novel computer-based decision aid on shared decision making for colorectal cancer screening: a randomized trial. Med. Decis. Making. 2011;31:93–107. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10369007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]