To the Editor:

While HRAS mutations have been identified in a few cases of non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the clinical course of patients with NSCLC with HRAS mutations has not been described. The following case discusses a patient with an HRAS-positive adenocarcinoma of the lung who experienced rapid clinical decline.

CASE PRESENTATION

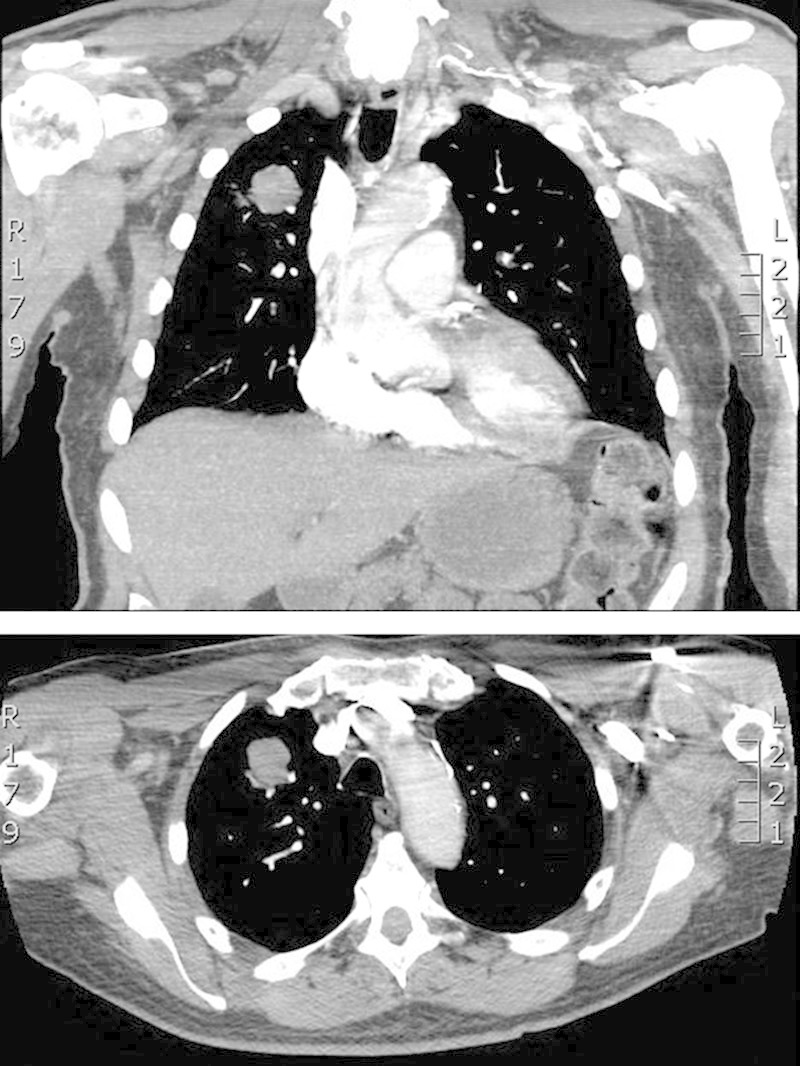

A 79-year-old male former smoker with a history of resected World Health Organisation (WHO) Grade I sphenoid meningioma presented to the emergency room, whereupon a computed tomography chest showed a 3-cm soft-tissue density in the anterior segment of the right upper lobes (Figs. 1 and 2). Moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma was confirmed by computed tomography-guided biopsy of the mass.

FIGURE 1.

Computed tomography chest with 3-cm soft-tissue density in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe.

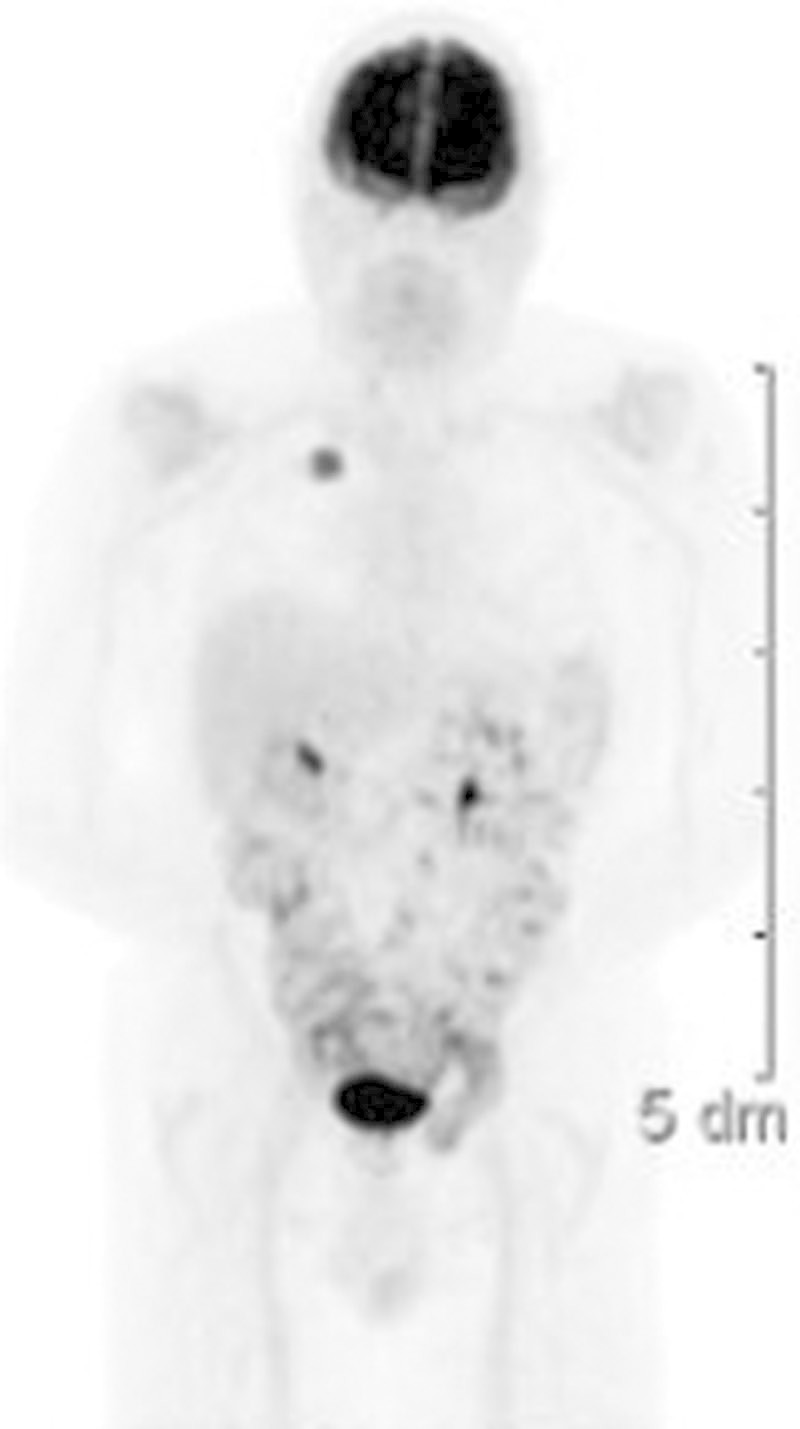

FIGURE 2.

Positron emission tomo graphy scan, notable for increased uptake (SUV 8) in the right upper lobe lesion only.

In September 2010, the patient underwent mediastinoscopy followed by right upper lobectomy. Final pathologic staging was T2aN0M0 (stage Ib) adenocarcinoma, large-cell subtype. The patient was treated with four cycles of pemetrexed and carboplatin.

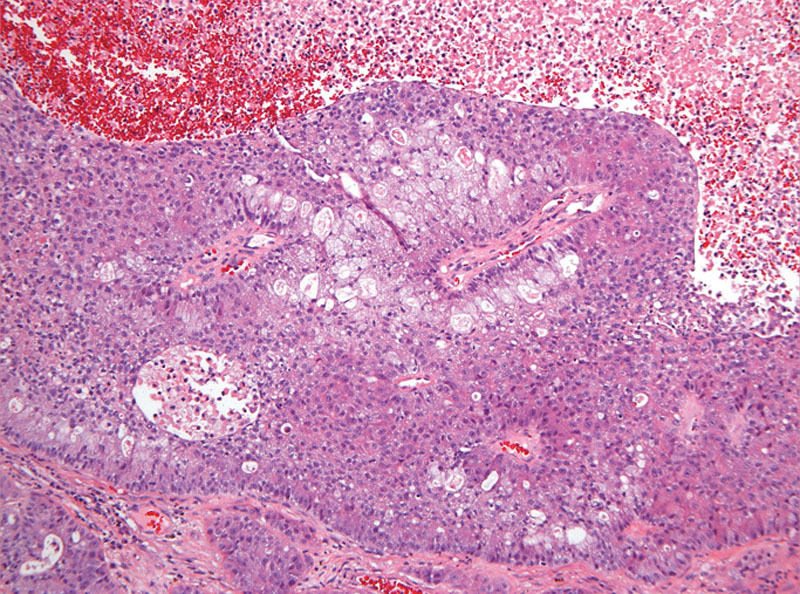

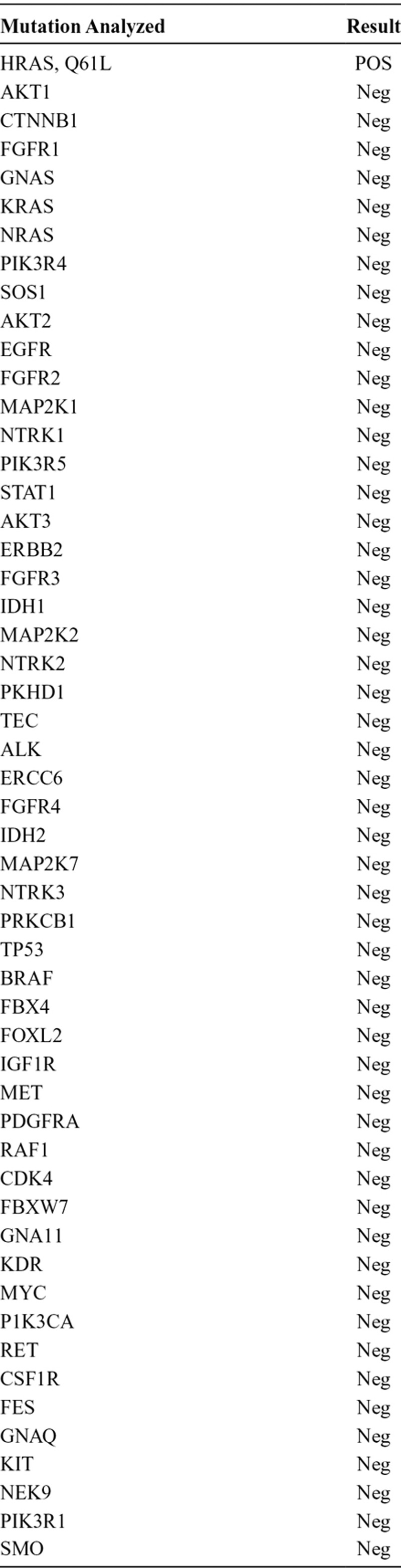

In July 2011, 10 months after completing the right upper lobectomy, the disease had metastasized to his brain. He underwent craniotomy for the left temporal lobe mass, followed by stereotactic radiosurgery of additional CNS lesions. Pathology of the temporal lobe lesion revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma consistent with metastasis from a lung primary (Fig. 3). Multiplex polymerase chain reaction/mass spectroscopy (MassARRAY system) was performed, testing for 647 known gene mutations in solid tumors (among 53 genes), and revealed one mutation, HRAS Q61L (Table 1). The patient’s previously resected meningioma was also tested for mutations using the same multiplex polymerase chain reaction/mass spectroscopy platform previously described, and no mutations were found in the meningioma, including no HRAS mutations.

FIGURE 3.

Histology of CNS metastases, adenocarcinoma of lung origin.

TABLE 1.

Mutation Analysis Performed, Only Positive for HRAS Q61L Mutation

Additional imaging revealed metastatic multiple bony lesions and innumerable liver lesions and bilateral adrenal lesions. The patient had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of three and was not a candidate for systemic palliative chemotherapy. The patient died in January 2012.

DISCUSSION

The case demonstrates a patient diagnosed with adenocarcinoma with HRAS mutation. The patient had a rapid progression from stage IB disease to metastatic adenocarcinoma and death.

Ras mutations are detectable in approximately 20% of lung cancers, with KRAS mutations representing 90% of those mutations. KRAS mutations are associated with a poor overall prognosis1 in NSCLC.

HRAS mutations have been documented in various cancer types (including cervical, salivary gland carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, prostate adenocarcinoma, breast, and both soft-tissue and osteosarcomas).2,3 HRAS mutations have also been described in Costello syndrome, also known as faciocutaneoskeletal syndrome, a rare genetic disorder characterized by mental retardation, cardiac abnormalities, and distinct facial features.4

HRAS mutations represent 1% of all mutations in NSCLC.5 Although infrequent, the role of HRAS in the pathogenesis of NSCLC is uncertain. Our patient with HRAS mutation had rapid progression from early stage NSCLC and died from metastatic disease less than 18 months after diagnosis. Additional cases with HRAS mutation are needed to evaluate the clinical behavior and prognostic features of HRAS mutant NSCLC. For this patient, the possibility of HRAS mutant NSCLC causing rapid disease progression and death from metastatic NSCLC raises the likelihood that HRAS mutations in NSCLC tumors are aggressive and associated with poor overall prognosis, similar to KRAS mutant NSCLC. Further research and description of clinical cases are needed for improved understanding of this genetic mutation in NSCLC.

Elizabeth Cathcart-Rake, MD

Christopher Corless, MD, PhD

David Sauer, MD

Ariel Lopez-Chavez, MD, MS

Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon

REFERENCES

- 1.Huncharek M, Muscat J, Geschwind JF. K-ras oncogene mutation as a prognostic marker in non-small cell lung cancer: a combined analysis of 881 cases. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1507–1510. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.8.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Da Silva L, Simpson PT, Smart CE, et al. HER3 and downstream pathways are involved in colonization of brain metastases from breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R46. doi: 10.1186/bcr2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bamford S, Dawson E, Forbes S, et al. The COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) database and website. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:355–358. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoki Y, Niihori T, Kawame H, et al. Germline mutations in HRAS proto-oncogene cause Costello syndrome. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1038–1040. doi: 10.1038/ng1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lea IA, Jackson MA, Li X, et al. Genetic pathways and mutation profiles of human cancers: site- and exposure-specific patterns. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1851–1858. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]