Abstract

Flow distributions in the heart and lung are heterogeneous but not at all random. The apparent degree of heterogeneity increases as one reduces the size of observable elements; the fact that the dispersion of flows shows a logarithmic relation to element size says that the system is statistically fractal. The fractal characterization is a statement that the system is nonrandom and that it shows correlation. The close near neighbor correlation has as the corollary of long tailing or falloff in correlation with distance, so called spatial persistence. Correlation can be expected because flow is delivered via a branching vascular system, and so it appears that the structure of the vasculature itself contributes. Since it is also practical and efficient for growth to occur via recursive rules, such as branch, grow, and repeat the branching and growing, it appears that fractals may be useful in understanding the ontological aspects of growth of tissues and organs, thereby minimizing the requirements for genetic material.

Keywords: angiogenesis, blood flow, correlation, heterogeneity, ontogeny

INTRODUCTION

Humans have but 100,000 genes made up from about 109 base pairs. There are about 250 different cell types in the body and each has a multitude of enzymes and structural proteins. The numbers of cells in the body is beyond counting. The numbers of structural elements in a small organ exceeds the numbers of genes; the heart has about 10 million capillary tissue units, each composed of endothelial cells, myocytes, fibroblasts and neurons. The lung has even more. Consequently, the genes, which form the instruction set, must command the growth of cells and structures most parsimoniously, and yet end up with functioning structures that last for decades. They even contain the instructions for their own repair!

From genome to geonome

The genome, the masterful instruction set, contains the list of ingredients, and the details of how to make the chemicals of our body. But how does this instruction set lead to the composite whole? What marvels of interactions allow growth, the formation of structural and functional units? The genotype gives rise to the phenotype, each one a different representation of the morphonome. The morphonome may be regarded as the set of measures of an individual of a species which gives a complete description of the structure of that individual. It includes the structure of the genome, the proteins, substrates, hormones, membranes, channels, organelles, cells, tissues, organs, and the composite body of the organism. The morphonome describes all the constituents of the body, and their spatial relationships to one another, and so defines the basis of life. Its reflections are found in the patterns of the phylogenetic tree. But it is not life, and in the Frankensteinian sense, the morphonome needs to be brought to life.

The description of life is the “physionome,” the physiological dynamics of the normal intact organism, from cell to sentient being. Cell-to-cell information exchange (via neural, hormonal, electrical mechanisms) governs biological function. Function affects phenotypic expression, and vice versa, so the morphonome is influenced by the physionome through growth, injury, training, and so on. Biological systems are regulated via multiple enzymic, humoral and neural controllers. Fractals and chaos come together in the expression of the morphonome and the physionome: we might generalize to imply that the morphonome is fractal, showing self-similarity at many levels, while the physionomic functions show self-similarity over space and time, the often chaotic processes occurring on a fractal substrate of structure.

The physionome encompasses molecular dynamics, the energetics of conformational change, enzyme regulation, and the regulation of phenotypic expression by cellular function or influences from neighboring cells. While most cells have the same biochemical capabilities, phenotypic expression results in great differences between different cell types. Even a relatively simple process such as cell ion regulation is governed by a large set of interacting processes which together perform remarkably precise homeodynamics. We use homeodynamics here to indicate that probably no cell constituent is really held at a constant (homeostatic) level, but that fluctuations are the rule. Integrated organ function is not a miracle, but it is a marvel of integrated chemical, mechanical, and electrical regulation. Without these we would not have “being” of a sentient form, or communication where locomotion, the activation of muscle, is the brain’s outlet to the world.

Functional physiology allows the development of a functional psyche, and there is good reason to look upon the psychonome as having its own structural fractal properties and chaotic dynamics. The psychonome is the quantitative description of the psychological dynamics of the intact organism within a normal environment. These may be illustrated by the interactions of sensory and motor functions with mood and energy levels, by the depression of disease or weakness, by the demands of the physical world’s coldness or heat or raw power over us.

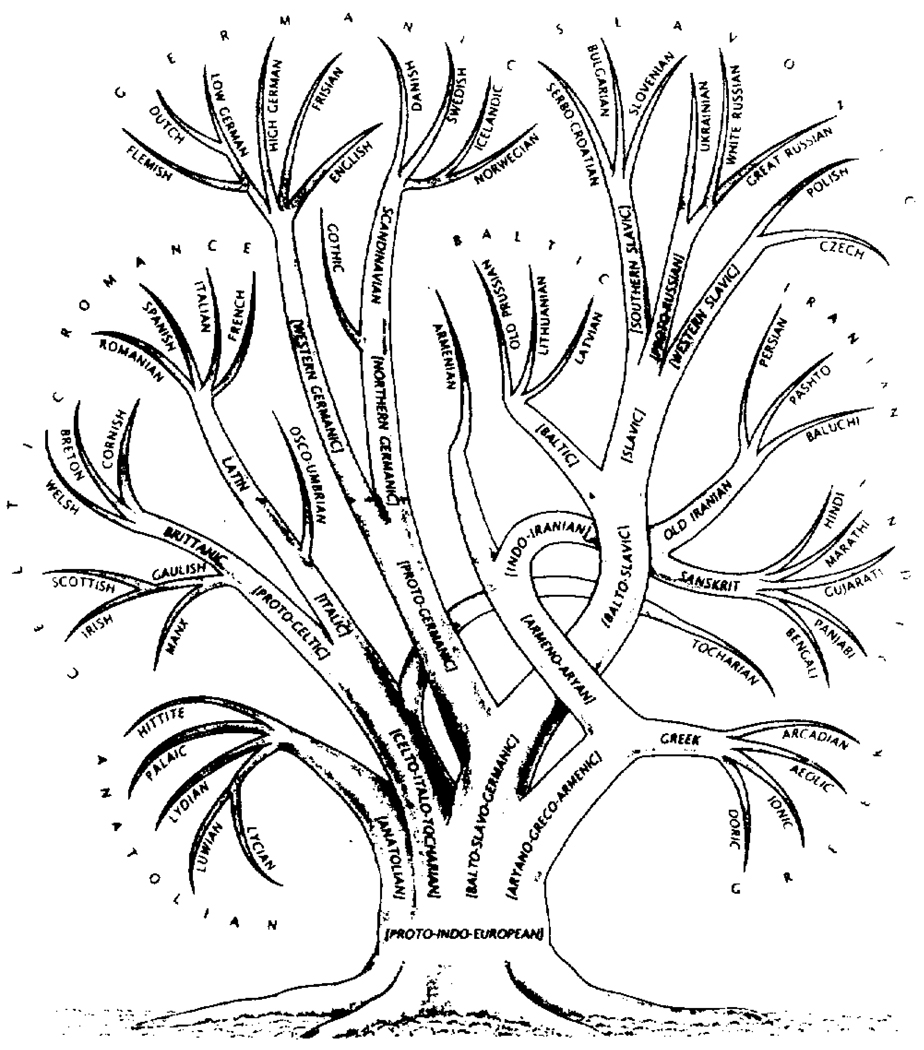

In groups our psyches interact to form the socionome, the behavior of groups, and the nature of the interactions between groups or societies, races, or nations. While this area of study has been closer to philosophy than to science, because measurement is so difficult, the socionome is now being more closely defined. It too has its fractal characteristics, as illustrated by the tree of languages shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Family tree of the Indo-European languages, traced back to the protolanguage that existed only 6000 years ago. Splits into dialects, then distinct languages and daughter languages are only now diminishing through the vehicle of worldwide communication of the twentieth century (from Gamkrelidze and Ivanov, 1990).

The geonome, the quantitative description of planet earth’s form and function, is the target of a huge amount of study. The topics range from the slow processes of plate tectonics to the more rapid processes of ozone layer depletion and of weather patterns. Though man is but one of many species, our inability to live in harmony with nature and our innate desire to exploit earth’s riches to the full is resulting in the destruction of species of animals and plants and the degradation of man’s habitat. Global warming may be changing the natural fluctuation of the earth’s temperature, the waxing and waning of ice ages. The chaotic oscillations in population densities induced by famine and pestilence must have their reflections now in the fluctuations in the state of the geonome. Nevertheless, as with deletions in the gene, some fluctuations will lead to extinctions.

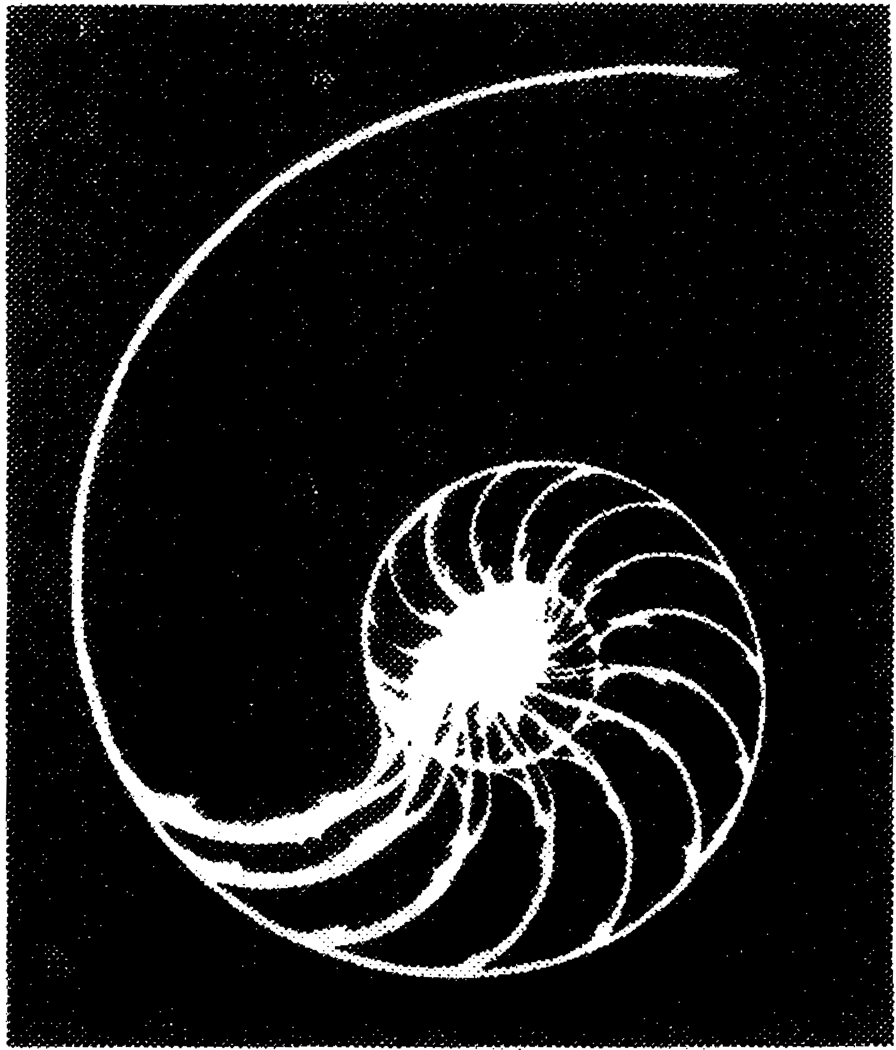

The background for the fractal descriptions of growth processes comes from the mathematicians and physicists as much as from the biologists. D’Arcy Thompson was one of the path finders, setting forth the principles of scaling of animal form with respect to form and function. His book “On Growth and Form” (1961, the abbreviated version of the 1925 original) covered the self-similar forms of spiral growth of snails and conches Fig. 2. The form is the logarithmic spiral, labelled the “Spira Mirabilis” by Bernoulli; the form is r = Aθ, where r is the radius, A a constant and θ the angle of rotation, so that the straight line from the center intersects the are at a constant angle independent of θ. The curve has the same shape at all magnifications. Thompson (1961) traces back the heritage of these ideas to the 17th century, observing, “Organic form itself is found, mathematically speaking, to be a function of time… We might call the form of the function an event in space-time, and not merely a configuration in space.”

Figure 2.

Sea shell, halved, showing the log spiral form (from Ghyka, 1977.)

Lindenmayer (1968) developed a formalism for describing developmental processes. These ideas evolved, like Thompson’s and Darwin’s, from observation. “In many growth processes of living organisms, especially of plants, regularly repeated appearances of certain multicellular structures are readily noticeable…. In the case of a compound leaf, for instance, some of the lobes (or leaflets), which are parts of a leaf at an advanced stage, have the same shape as the whole leaf has at an earlier stage.” His L-systems were developed first for simple multicellular organisms, but developed a theoretical life of their own, serving as the basis for computational reconstructions of beautiful portrayals of plants and flowers (Prusinkiewicz et al., 1990). The idea of a leaf being composed of its parts is the basis of Barnsley’s Collage theorem which he used to construct, for example, a wonderfully realistic fern (Barnsley, 1988).

Vascular branching patterns were being explored without putting them in terms of fractals, and even now it is not proven that they must be fractal. Horsfield and colleagues (Singhal et al., 1973) embarked on a magnificent series of studies related to the lung vasculature and airways, following some of the strategies taken from Strahler’s geomorphology (Strahler, 1957). The work reflected approaches initiated by the renowned anatomist-morphometrist Ewald Weibel with Domingo Gomez who had an innovative flair for mathematical applications (Weibel and Gomez, 1962).

The growth patterns in mammals are neither simple nor primitive. The huge number of evolutionary steps has led to vascular growth processes which are highly controlled, well behaved patterns which are precisely matched to the needs of the organ. A glance at a casting of the microvasculature reveals to the eye a pattern that uniquely identifies the organ, even though none of the cells remain to show the fundamental structure of the organ. In general, there is a capillary beside every cell of the organ, to bring nutrient and remove waste with minimal diffusion distance. The principles of optimality applied to growth raise questions. Which functions are to be optimized? Minimize vascular volume? Minimize delivery times for oxygen? Minimize the mass of material in the vascular wall? Minimize the energy required to deliver the substrates to the cell? As Lefèvre (1983) expressed it, one must find the cost function for the optimization. The cost function is the weighted sum of the various features that are to be minimized; we need to figure out the Grand Designer’s definition of the cost function in order to gain deeper understanding of the total processes involved in growth, deformation, remodeling, dissolution, and repair.

What is clear is that growth of a particular cell type requires the collaboration of its neighbors. A heart does not develop well from the mesodermal ridge unless the nearby neural crest is also present (Kirby, 1988). The endoderm seems also to be necessary (Icardo, 1988); this is not surprising for we now recognize the importance of endothelial derived growth factors.

The majority of explorations of branching fractals has been with simple dichotomous branching, variants on the binary tree. There are plants which have triple, quadruple and higher branching ratios, particularly near the flowers or terminal leaf groups, but the trunks of deciduous trees tend towards binary branching. From the algorithmic point of view it probably does not matter much, because a ternary branch can be regarded as approximating two binary branches with a short link between them.

No matter how the system forms, branching is the hallmark of fractal systems, from watershed geomorphology to neural dendrite formation. In this essay we explore some of the growth mechanisms and patterns. In concentrating on spatial structuring we will ignore the dynamical fluctuations in flows with the vasculature (Bassingthwaighte, 1991).

PRIMITIVE GROWTH PATTERNS

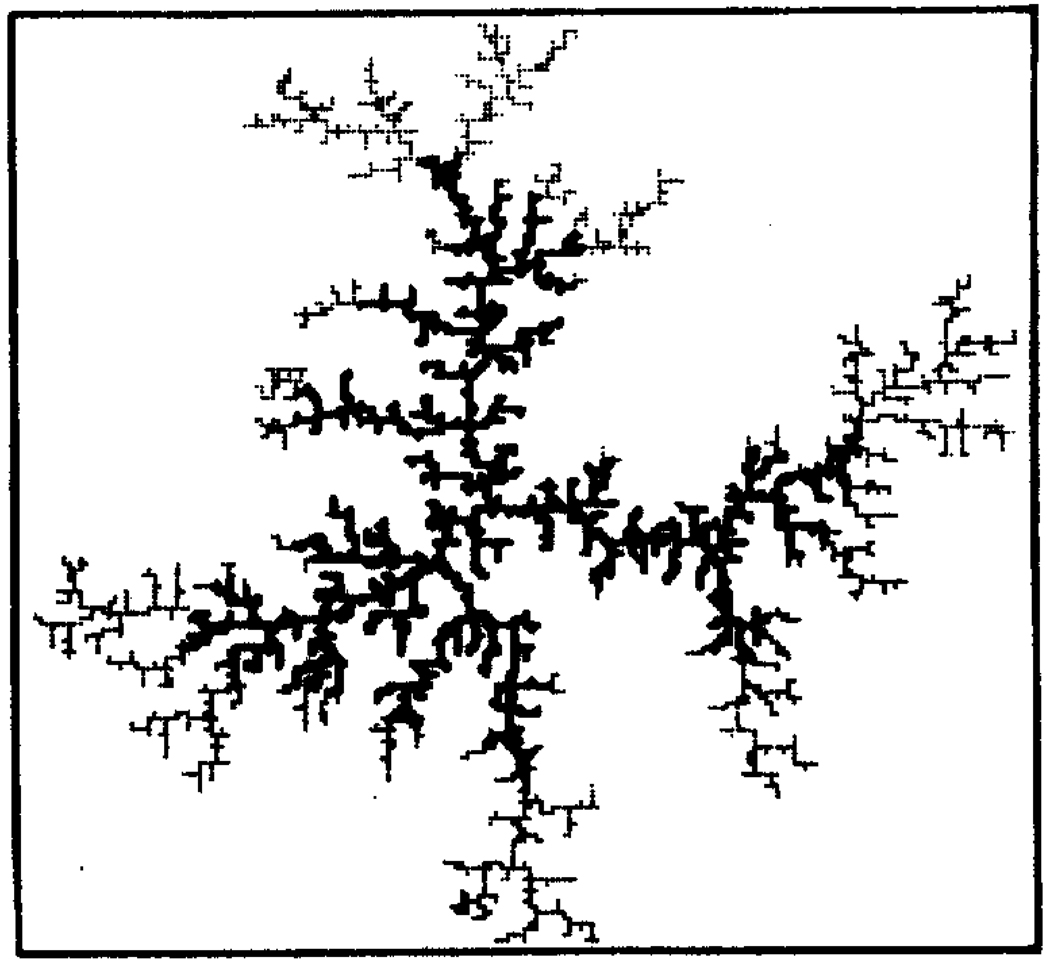

Diffusion-limited aggregation

Witten and Sander (1983) introduced an algorithm that mimics a large number of processes. The original incentive was to consider the deposition of a metallic ion from a solution of low concentration onto a negative electrode. Diffusing randomly in the solution, the ions stick to the electrode when they hit it, and so coat the electrode. The surface coat is not smooth, but has a tree-like structure. Their model was this: In a plane, place a seed particle to which others will stick; then release another particle into the field at a distant point and let it diffuse randomly. If it should happen to hit the seed particle, let it stay in the adjacent position in the lattice. Repetition of this process leads to the formation of complex clusters of intriguingly general form. One of their clusters is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

A small cluster of 3000 particles formed by diffusion-limited aggregation. The first 1500 points are larger, and paucity of small dots attached to the earliest deposits indicates that very few particles penetrate the into the depths of the cluster, but are caught nearer the growing terminae (from Witten and Sander, 1983).

This simply constructed DLA pattern is remarkably universal, and a good many variants may be seen in Vicsek’s book (1989) and in an attractive small picture book edited by Guyon and Stanley (1991), ranging from electrical discharge patterns to retinal arteries (Family et al., 1989) and the form of a retinal neuron (Caserta et al., 1990).

COMPUTER GROWTH ALGORITHMS

The exercise of developing growth algorithms is growing faster than the vasculature in an embryo it seems. The challenge is to find algorithms which have simple rules and yet reproduce the general form of vascular structures. The task is nontrivial, and although there are some real successes, no truly satisfactory algorithms are yet in hand. This is in part because each tissue is different from all others: a casting of the vasculature of a particular organ can be identified as to its origin without any tissue being present; the form of the vasculature alone is enough of a clue. Stated conversely, the structure and arrangement of the cells in a tissue so dominate the form of the microvasculature that the casting identifies the cell arrangement. What this means is that vascular growth algorithms cannot successfully mimic vascular form without mimicking tissue cell arrangements. Thus the successes so far are limited, but on the other hand it is to be admired that they can go as far as they do, handicapped as they are by lacking a representation of the tissue.

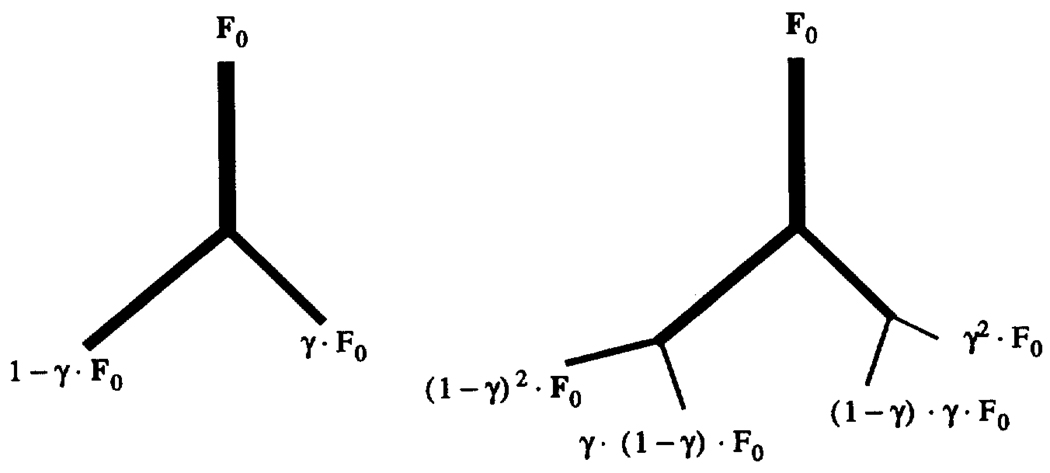

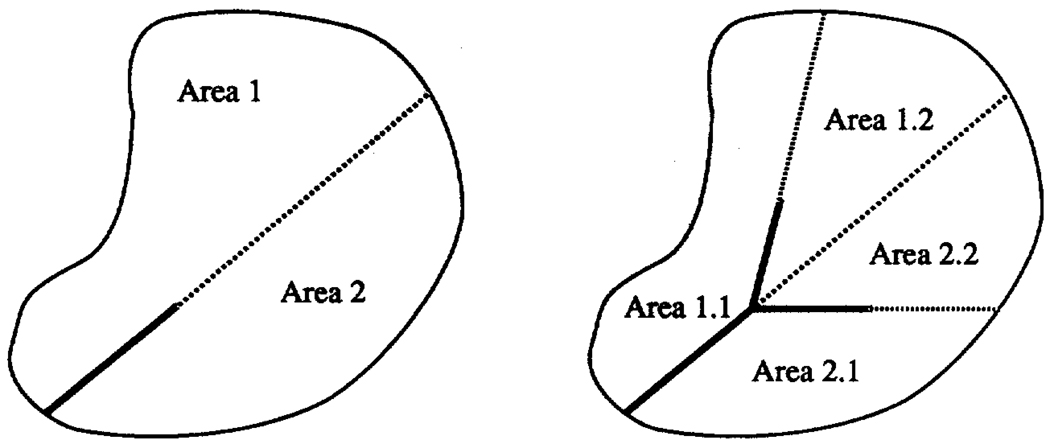

Dichotomous branching is a natural starting point (Mandelbrot, 1983). Branching of trees and blood vessels is very nearly purely dichotomous, and trichotomous branching can even be regarded as mathematically equivalent to having two dichotomous branchings close together. Simple symmetric dichotomous branching is a binary tree, and is not so interesting because it gives rises to a uniform distribution of flows at any given level or generation of branching. However, simple asymmetric branching can give rise to heterogeneous flow distributions; an example from van Beek et al. (1989) is shown in Fig. 4. The fraction of flow entering one branch is γ, and that entering the other is 1-γ, van Beek et al. found that a γ of around 0.47 created enough asymmetry to match the observed variances in flows in the heart, as did Glenny et al. (1991) in the lung. Several variations on the theme worked almost equally well, and small degrees of random asymmetry served as well as did fixed degrees of asymmetry.

Figure 4.

Dichotomously branching fractal model. Left: basic element in which fractions γ and 1 – γ of total flow F0 are distributed to daughter branches. Right: flow at terminal branches in network of two generations (from Glenny and Robertson, 1991).

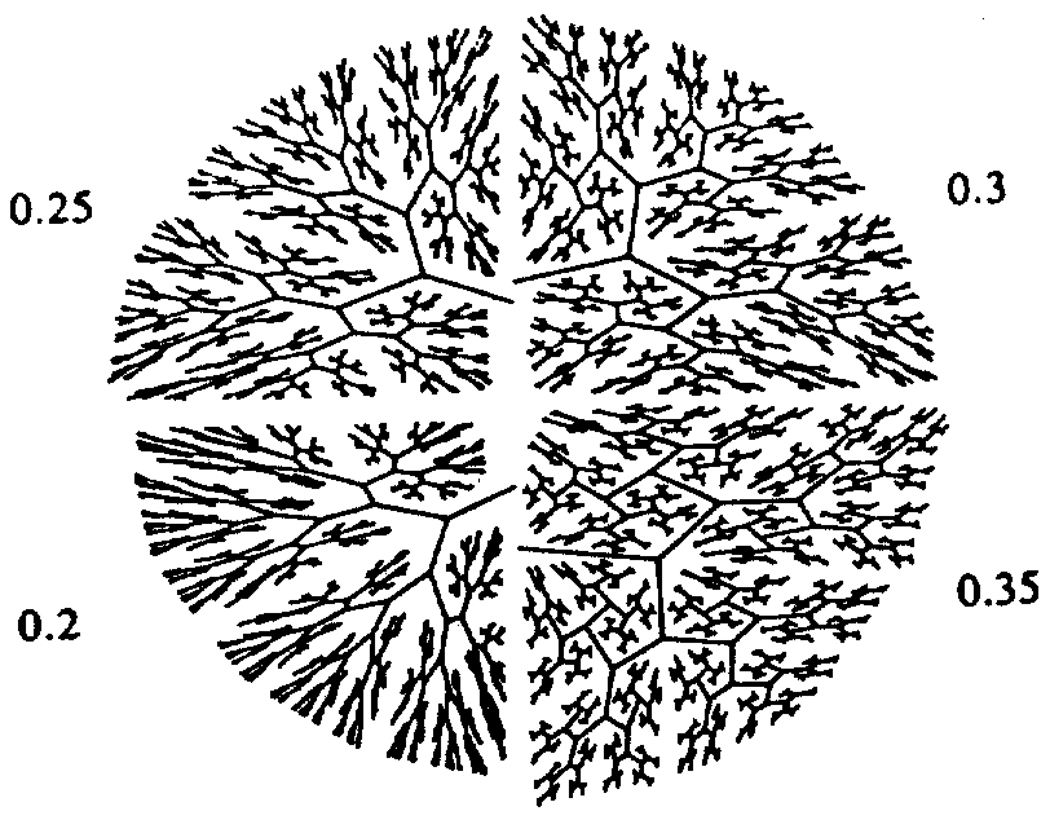

The simplest of dichotomous algorithms are unrealistic in the sense that they disregard the constraints imposed on vascular patterns, specifically to be confined within a three-dimensional domain, and to fill all of that domain. This is illustrated (and calculated) more readily for a two-dimensional setting than for a three-dimensional one, as in Fig. 5. The algorithm illustrated is to split the area exactly in half with a projected line and to proceed along this line to a point a specified fraction of its total length, e.g. one third. From this point repeat the algorithm to split the areas of each of the two halves, and in each case to extend the line (the artery) to the same fraction of the lines total length, as in stage 2. This is the algorithm used by Wang et al. (1991) as an example; it needs to be done in three dimensions rather than two, but did have the virtues of looking fairly realistic, as well as being space-filling. Fig. 6 shows the results of such an algorithm plotted for different fractional lengths of growth: values of fractional length of 0.2 and 0.25 look unnatural compared to those using 0.3 and 0.35. The short fractions give rise to excessively long terminal branches; fractional lengths of 0.4 or higher have excessively long large branches and too stubby terminal branches. Thus the algorithm could be improved by adding more rules, e.g., the ratios of lengths should lie within a specified range over several generations, as has been observed in real systems (e.g., Suwa and Takahashi, 1971).

Figure 5.

Area splitting algorithm for two dimensional dichotomous branching system filling the space available. The rule is this: from a starting point, draw a line to split the area available, and proceed along the line a specific fraction of its length (stage 1). Repeat this, splitting both halves (stage 2).

Figure 6.

Area-dividing branching algorithm applied to quarter circles. The patterns are strikingly dependent on this value of the fractional distance to the far boundary (figure provided courtesy of C.Y. Wang and L.B. Weissman).

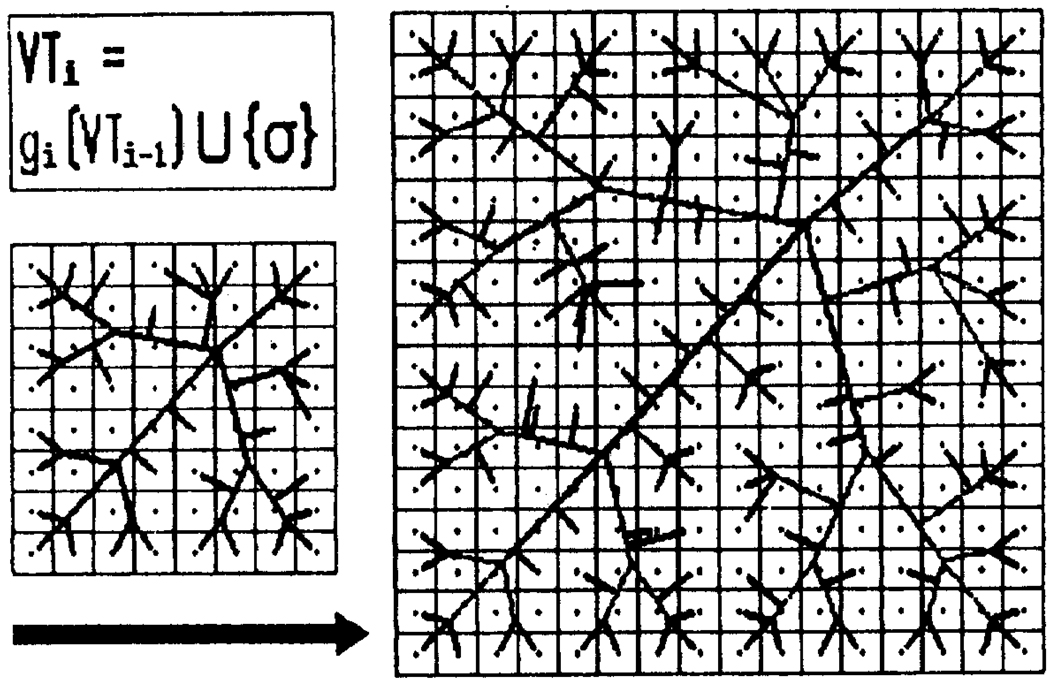

Improvements in this algorithm have been made in many ways. A principal problem was that the domain shape and size were preordained, which is not the way growth occurs. Gottlieb (1992) proposed an algorithm (Fig. 7) which accounts for growth by symmetric enlargement, and for vascular budding by stimulus from tissue (as if by a growth factor) when there is no capillary sufficiently close to a tissue element. Whether these algorithms account for the pressure and flow distributions in the microvasculature is not known.

Figure 7.

Tissue expansion followed by vascular sprouting. In a given iteration the cells (the squares) divide and grow (one cell → 4 cells here); the matching growth function g resizes the existing vessels, then new vessels are located in regions of insufficiency and the sprouts added to the structure (from Gottlieb, 1992, with permission of IEEE).

Fenton and Zweifach (1981) mapped the vasculature of the conjunctivae of humans and the omentum of rabbits in order to develop a statistical base for describing the network geometry and to calculate pressure and flows. They found branching ratios greater than 2.0, namely 2.3, more than dichotomous; from the length and branching ratios they created networks which gave the right kind of pressure distributions as a function of position along the length of the vessels. Dawant et al. (1986) extended these probabilistic network formulations, with the result that they could describe the influences of variability in lengths versus diameters on the distributions of flows in the small terminal branches; Levin et al. (1986) extended this to showing the expected variability in hematocrits, and the degree of separation of plasma and RBC’s in traversing the capillary bed.

The theories so far developed are incomplete. Gottlieb’s growth algorithm is the only one allowing anastomoses at a range of levels. I classify the anastomosing mosaic network of Kiani and Hudetz (1991) as a different type of structure, based as it was on branching angles and resulting in randomly sized intercapillary spaces of polygonal form in a plane square. (Plane-tiling polygons average, mathematically, six sides, as described by Grünbaum and Shephard, 1987). Missing are the constraints of how the tissue cells grow, divide and arrange themselves to serve the organs function. The general rule of one capillary beside each cell is a good one for vascular tissues, even if not for bone and cartilage, and will serve as a rough measure of how many capillaries are needed by a tissue. The questions of how many capillaries there are per arteriole, and what size the terminal microvascular unit is, remain unanswered for most tissues.

While all of the algorithms mentioned above are fractal, by virtue of having constant (more or less) ratios of lengths, diameters, etc., only a few have been carefully compared to the actual anatomy, and of these almost none to the actual distributions of flows. A fractal algorithm recently developed by Krenz et al. (1991) for the lung microvasculature uses branching ratios greater than two and through the incorporation of randomization of the resistances at each bifurcation gives rise to the degrees of flow heterogeneity seen in nature. Thus the model can be based on average ratios for branching, length, and diameters, and also provide flow heterogeneities equivalent to those modeled by van Beek et al. (1989) and Glenny et al. (1991).

VASCULAR GROWTH PATTERNS

The hallmark of capillary growth patterns is that their arrangement follows that of the cells of the tissue. Where there are either long cylindrical muscle cells as in skeletal muscle (Mathieu-Costello, 1987), or cells in syncytia in series, as in the heart (Bassingthwaighte, Yipintsoi and Harvey, 1974), the capillaries are arrayed in long parallel groups serving a set of parallel muscle fibres within a bundle. Likewise, in a glandular organ the capillaries are arrayed around the secreting cells forming an acinus, as modeled by Levitt et al. (1979). These are not fractal and even though there is self-similarity of a sort in the glandular system of the gastrointestinal tract, as illustrated by Goldberger et al. (1990), the capillaries themselves form the terminal units of the vascular system. While both arterial and venous systems may show self-similar branching the capillaries show only branches connecting to equal sized or larger vessels. Nevertheless we pay much attention to capillary growth since it is from these vessels in embryonic and later growth phases that the arteries and veins develop. As Wiest et al. (1992) put it so nicely “Physiological growth of arteries in the rat heart parallels the growth of capillaries, but not of myocytes.” The point is not a subtle one, for even though the capillary budding is surely stimulated by the growth and nutrient requirements of the myocytes, and the capillaries provide for the flow of nutrients and the removal of metabolites, it is the arterioles and venules that serve the capillaries, and in turn the larger arteries and veins which serve the microvasculature.

The answer to the chicken and egg question is clear with respect to vascular growth. The serial nature of the processes of growth of the vasculature in the heart is discussed by Hudlická (1984) and Hudlická and Tyler (1986). Their observations are certainly in line with the general view of vascular growth proposed by Meinhardt (1982). As parenchymal cell growth occurs there is budding of capillary endothelial cells (Rhodin and Fujita, 1989), initially protruding into the interstitial space, then developing a bulge which forms the end of a plasma tube like the bottom of a test tube, and the tube lengthens so that an erythrocyte may be seen to oscillate within it. By some magic, perhaps related to the way that endothelial cells grow to confluence in monolayers, the sprouting capillary reaches out toward another capillary and joins to it, allowing the flow of plasma and then erythrocytes. Remodeling occurs; as vessels grow there are rearrangements of the flow paths, and occasionally, as shown in one of Hudlická’s (1984) figures, a capillary may disappear. It is commonly said that smooth muscle cells “migrate” from the larger arterioles into the smaller ones, it seems more likely that cell differentiation occurs because of local stimuli such as pressure oscillations, flow-dependent growth factors (Langille et al., 1989). The intricate mechanisms by which such growth and transformation is controlled are slowly becoming identified, but go far beyond the scope of this essay.

Vascular growth occurs in parallel with tissue growth; tumors that outgrow their vascular supply are the exception to this. The biochemical rules for this may be complex, but the simplest elements of the process are not: the buddings that start as capillaries are simple, dichotomous branchings. It is no wonder then that dichotomous branchings are the commonest seen in the adult tissue. Thus the algorithmic rules might be reduced, albeit too simplistically, to be:

-

-

bud or branch and extend,

-

-

repeat the operation recursively.

Gottlieb’s (1992) article provides many illustrations of vascular patterns which can be rather realistically matched by his growth and sprout algorithm, which demonstrates that very simple algorithms can go a long way toward description even if not explanation.

It is these types of growth which presumably give rise to the fractal relationships between the degree of apparent heterogeneity of local tissue blood flows within an organ and the resolution of the measurement (the size of the tissue elements over which an average flow is measured). Bassingthwaighte, King and Roger (1989) found the heterogeneity-element size relationship in the hearts of baboons, sheep and rabbits to be linear on a log-log plot, i.e., a power law relationship the slope of which gives a fractal dimension, D, of 1.2. This fractal D, being greater than 1.0, indicates that the system is self-similar over the observed range and that the heterogeneity is not random. The value of D is 1.5 for random processes. Bassingthwaighte and Beyer (1991) show that this translates into a measure of correlation falling off with distance. Van Beek et al. (1989) show that fractal branching processes can explain the heterogeneity.

The 1962 study of Weibel and Gomez pioneered the quantitative analysis of the lung’s vascular and airway systems. In his 1963 work (Weibel 1963) portrayed the hexagonal nature of the structures. (Incidentally, Weibel and coworkers did the first analysis of mammalian tissue that was labeled “fractal”, using the approach for the estimating surface areas within mitochondria (Paumgartner et al., 1982)). Horsfield (1978) characterized the branching of the vascular system, developing a classification that differed a little from that of Strahler (1957). Working on the geographical structuring of watersheds, and lungs, Woldenberg (1970) devised a system for examining spatial structures in a hierarchical fashion, wherein the hexagonal structures that dominated hills and watershed regions, were seen to have repetitive structuring, a statistical self similarity. The constraint that spaces or surfaces must fit together gave rise to a numerical way of defining the number of fields or regions as a logarithmic function of the fineness of the divisions used. These numerical relationships applied also to the lung vascular and airway systems, and the liver vasculature. Woldenberg (1986) extended his analysis of the lung data to consider the cost minimization in structuring the vascular system, that is minimizing arterial and venous surface areas, volume, power and drag, and framing these considerations in terms of the physics of the branching, in tune with the approach of Lefèvre (1983).

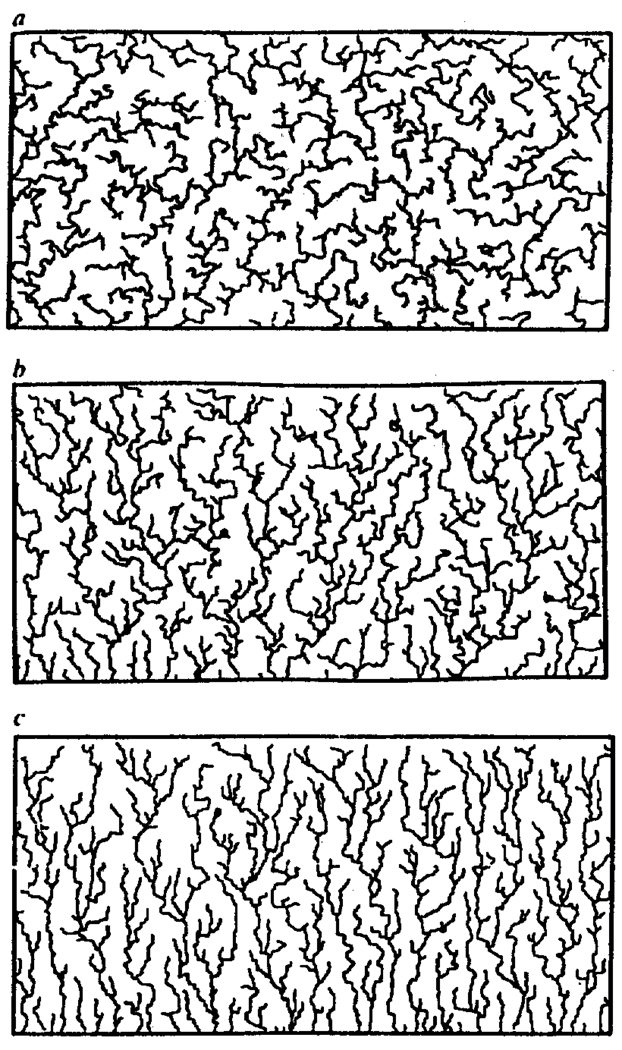

These efforts are an approach to the inverse problem, which is to discover in retrospect what nature’s growth rules might be. If one starts with a simple view, as I did above, one soon discovers the shortcomings of that view, and so modifies it to fit better with reality. Stark’s (1991) explorations of drainage networks are quite analogous to our explorations of vascular growth. His route to the recognition that there is an asymmetric force influencing stream growth (Fig. 8) is exemplary; in fact, the directionality of vascular flows, and the self-avoiding path generation are very similar. Continuing in this earthy vein, it is also sensible to keep in mind that it is most unlikely that a single fractal rule governs a system: Burrough (1983) shows how a hierarchical set of fractal processes, each extending over a limited range, can provide a more realistic description of soil structures. This is probably what we need to do to understand growth processes through the full range of generations of vascular growth. The term that is used is multifractal. Prusinkiewicz and Hanan (1989) use Lindenmayer’s recursive sets of rules to develop analogs to plants, and illustrate extensions of this to cell growth and division, and even to music. In any case, the applications to mammalian systems need to be begun.

Figure 8.

Examples of simulated drainage networks grown by the self-avoiding invasion percolation method. Numerical simulations were set up using a square site-bond lattice in which random bond strengths were normally distributed lattice size is 512 × 256. Seeding was allowed from every other point along the bottom edge. In this case invasion of the lattice was allowed to continue until no further free sites were available. Strahler stream ordering was applied: streams of order four and above are shown. The substrate becomes steadily more susceptible to northward growth from a (isotropic lattice) to c (strongly anisotropic lattice). The fractal dimension dmin of the principal streams is invariant to this anisotropy and is on average 1.30 throughout (from Stark, 1991).

PHYLOGENY VERSUS ONTOGENY

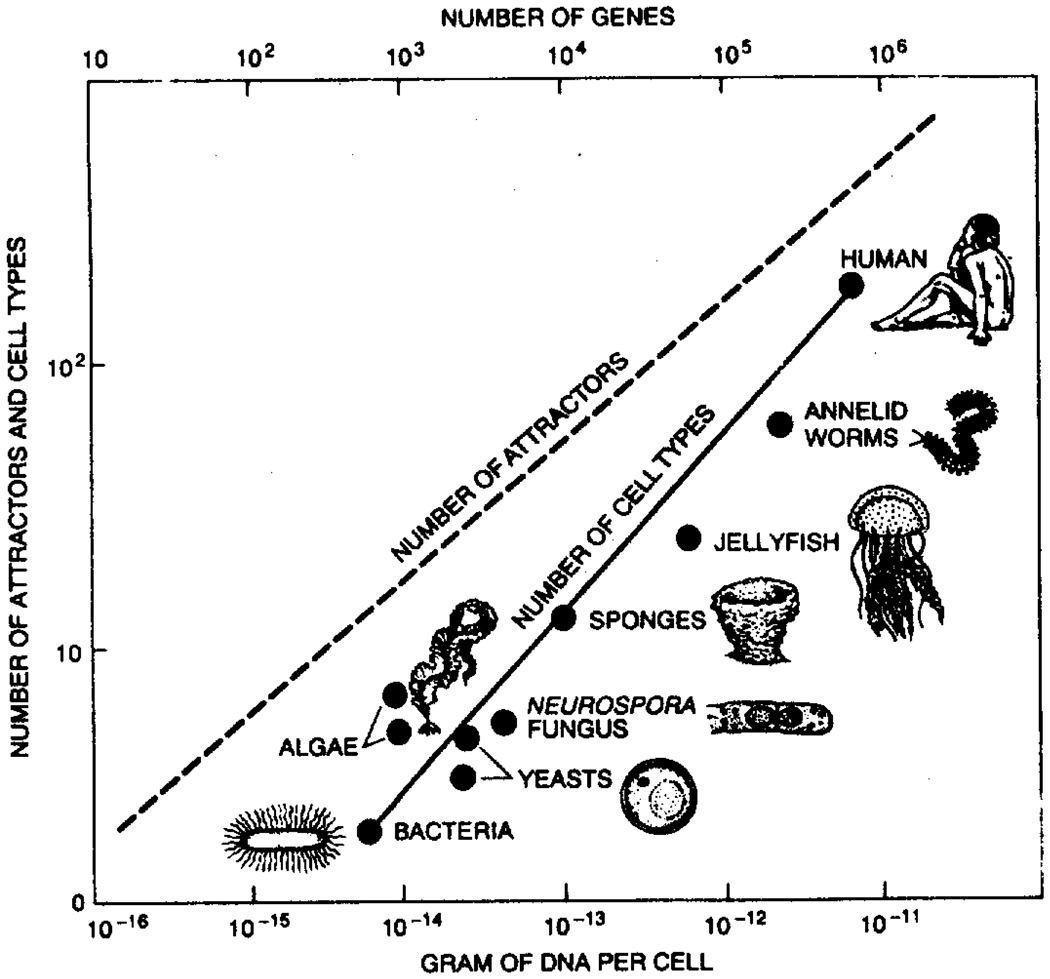

Presumably fractal growth processes do not apply to the growth of phylogenetically determined structures. While it is true that disturbing the environment for the growing structures disturbs the form of structures that have evolved through the phyla (Icardo, 1988), what is equally clear is that the body’s major vessels, extending down to the form of the largest vessels feeding an organ, have very similar forms within a species and from species to species. Such uniformities cannot be attributed to opportunistic processes such as appear to work for capillary growth. But phylogenetically controlled processes cost genes, and given that we have so few, it makes sense that they be retained for the most important structural features only. Advanced animals have more complex structures, and the capacity for complexity, measured in terms of the numbers of genes or the amount of DNA seems to match the observed complexity, measured in terms of the numbers of cell types, as shown in Fig. 9 from Kauffman (1991).

Figure 9.

Number of cell types in organisms seems to be related mathematically to the number of genes in the organism. In this diagram the number of genes is assumed to be proportional to the amount of DNA in a cell. If the gene regulatory systems are K = 2 networks, then the number of attractors in a system is the square root of the number of genes. The actual number of cell types in various organisms appears to rise accordingly as the amount of DNA increases. The “K = 2 networks” refers to a simple system wherein the connections between neighbors in a planar array control whether an element is active or not, a kind of binary level of control that is about the simplest conceivable for a multielement system (from Kauffman, 1991).

SOME FRACTAL GROWTH PROGRAMS

Most algorithms are better for unconstrained branching than for constrained. Programs that run on home computers can illustrate the phenomena. Garcia (1991) reviews related ideas, van Roy’s Designer Fractal (1988) allows one to create complex patterns by repetitively replacing line segments. The iterated function systems of Barnsley (1988) are available on a Macintosh (Lee and Cohen, 1990). Lauwerier’s (1991) book lists programs in Basic that make trees, etc.

REFERENCES

- Barnsley MF. Fractals Everywhere. Boston: Academic Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bassingthwaighte JB, Yipintsoi T, Harvey RB. Microvasculature of the dog left ventricular myocardium. Microvasc Res. 1974;7:229–249. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(74)90008-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassingthwaighte JB, King RB, Roger SA. Fractal nature of regional myocardial blood flow heterogeneity. Circ Res. 1989;65:578–590. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.3.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassingthwaighte JB, Beyer RP. Fractal correlation in heterogeneous systems. Physica D. 1991;53:71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bassingthwaighte JB. Chaos in the Fractal Arteriolar Network. In: Bevan JA, Halpern W, Mulvany MJ, editors. The Resistance Vasculature. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press; 1991. pp. 431–449. [Google Scholar]

- Burrough PA. Multiscale sources of spatial variation in soil. I. The application of fractal concepts to nested levels of soil variation. J Soil Sci. 1983;34:577–597. [Google Scholar]

- Burrough PA. Multiscale sources of spatial variation in soil. II A non-Brownian fractal model and its application in soil survey. J Soil Sci. 1983;34:599–620. [Google Scholar]

- Caserta F, Stanley HE, Daccord G, Hausman RE, Eldred W, Nittmann J. Photograph of a retinal neuron (nerve cell), the morphology of which can also be understood using the DLA archetype. Phys Rev Lett. 1990;64:95. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.64.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawant B, Levin M, Popel AS. Effect of dispersion of vessel diameters and lengths in stochastic networks. I. Modeling of microcirculatory flow. Microvasc Res. 1986;31:203–222. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(86)90035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Family F, Masters BR, Platt DE. Fractal pattern formation in human retinal vessels. Physica D. 1989;38:93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton BM, Zweifach BW. Microcirculatory model relating geometrical variation to changes in pressure and flow rate. Ann Biomed Eng. 1981;9:303–321. [Google Scholar]

- Gamkrelidze TV, Ivanov VV. The early history of indo-european languages. Sci Am. 1990;262:110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia L. The Fractal Explorer. Santa Cruz, CA: Dynamic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ghyka M. The Geometry of Art and Life. New York: Dover; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Glenny R, Robertson HT, Yamashiro S, Bassingthwaighte JB. Applications of fractal analysis to physiology. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:2351–2367. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.6.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenny RW, Robertson HT. Fractal modeling of pulmonary blood flow heterogeneity. J Appl Physiol. 1991;70:1024–1030. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.3.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberger AL, Rigney DR, West BJ. Chaos and fractals in human physiology. Sci Am. 1990;262:42–49. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0290-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb ME. The VT model: A deterministic model of angiogenesis. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1992 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Grünbaum B, Shephard GC. Tilings and Patterns. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Guyon E, Stanley HE. Fractal Forms. Haarlem, The Netherlands: Elsevier/North-Holland; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Horsfield K. Morphometry of the small pulmonary arteries in man. Circ Res. 1978;42:593–597. doi: 10.1161/01.res.42.5.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudlická O. Development of microcirculation: capillary growth and adaptation. In: Renkin EM, Michel CC, editors. Handbook of Physiology. Section 2: The Cardiovascular System Volume IV. Bethesda, Maryland: American Physiological Society; 1984. pp. 165–216. [Google Scholar]

- Hudlická O, Tyler KR. Angiogenesis. The growth of the vascular system. London: Academic Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Icardo JM. Heart anatomy and developmental biology. Experientia. 1988;44:910–919. doi: 10.1007/BF01939884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman SA. Antichaos and adaptation. Sci Am. 1991;265:78–84. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0891-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiani MF, Hudetz AG. Computer simulation of growth of anastomosing microvascular networks. J Theor Biol. 1991;150:547–560. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80446-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby ML. Role of extracardiac factors in heart development. Experientia. 1988;44:944–951. doi: 10.1007/BF01939888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenz GS, Linehan JH, Dawson CA. A fractal continuum model of the pulmonary arterial tree. J Appl Physiol. 1991 doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.6.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langille BL, Bendeck MP, Keeley FW. Adaptations of carotid arteries of young and mature rabbits to reduced carotid blood flow. Am J Physiol (Heart Circ Physiol 25) 1989;256:H931–H939. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauwerier H. Fractals. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Cohen Y. Fractal Attraction 1.0. St. Paul: Sandpiper Software; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lefèvre J. Teleonomical optimization of a fractal model of the pulmonary arterial bed. J Theor Biol. 1983;102:225–248. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(83)90361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin M, Dawant B, Popel AS. Effect of dispersion of vessel diameters and lengths in stochastic networks. II. Modelling of microvascular hematocrit distribution. Microvasc Res. 1986;31:223–234. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(86)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt DG, Sircar B, Lifson N, Lender EJ. Model for mucosal circulation of rabbit small intestine. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:E373–E382. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.237.4.E373. (Endocrinol Metab Gastrointest Physiol 6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer A. Mathematical models for cellular interactions in development. I. Filaments with one-sided inputs. J Theoret Biol. 1968;18:280–299. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(68)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmayer A. Mathematical models for cellular interactions in development, II. Simple and branching filaments with two-sided inputs. J Theoret Biol. 1968;18:300–315. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(68)90080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot BB. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Co; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu-Costello O. Capillary tortuosity and degree of contraction or extension of skeletal muscles. Microvasc Res. 1987;33:98–117. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(87)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt H. Models of Biological Pattern Formation. New York: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Paumgartner D, Losa G, Weibel ER. Resolution effect on the stereological estimation of surface and volume and its interpretation in terms of fractal dimensions. J Microsc. 1981;121:51–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1981.tb01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusinkiewicz P, Hanan J. Lecture Notes in Biomathematics: Lindenmayer Systems, Fractals, and Plants. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Prusinkiewicz P, Lindenmayer A, Hanan JS, Fracchia FD, Fowler DR, de Boer MJM, Mercer L. The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodin JAG, Fujita H. Capillary growth in the mesentery of normal young rats. Intravital video and electron microscope analyses. J Submicrosc Pathol. 1989;21:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal S, Henderson R, Horsfield K, Harding K, Cumming G. Morphometry of the human pulmonary arterial tree. Circ Res. 1973;33:190–197. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark CP. An invasion percolation model of drainage network evolution. Nature. 1991;352:423–425. [Google Scholar]

- Strahler AN. Quantitative analysis of watershed geomorphology. Trans Am Geophys Union. 1957;38:913–920. [Google Scholar]

- Suwa N, Takahashi T. Morphological and Morphometrical Analysis of Circulation in Hypertension and Ischemic Kidney. Munich: Urban & Schwarzenberg; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DAW. On Growth and Form. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- van Beek JHGM, Roger SA, Bassingthwaighte JB. Regional myocardial flow heterogeneity explained with fractal networks. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:H1670–H1680. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.5.H1670. (Heart Circ Physiol 26) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Roy P, Garcia L, Wahl B. Designer Fractal. Mathematics for the 21st Century. Santa Cruz, California: Dynamic Software; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Vicsek T. Fractal Growth Phenomena. Singapore: World Scientific; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Weissman L, Bassingthwaighte JB. Bifurcating Distributive System using Monte Carlo method. Mathematical Modelling. 1991 doi: 10.1016/0895-7177(92)90050-U. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel ER, Gomez DM. Architecture of the human lung. Science. 1962;137:577–585. doi: 10.1126/science.137.3530.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel ER. Morphometry of the Human Lung. New York: Academic Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Wiest G, Gharehbaghi H, Amann K, Simon T, Mattfeldt T, Mall G. Physiological growth of arterioles in the rat heart parallels the growth of capillaries, but not of myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1992 doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(92)91083-h. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten TA, Sander LM. Diffusion-limited aggregation. Phys. Rev. B. 1983;27:5686–5697. [Google Scholar]

- Woldenberg MJ. A structural taxonomy of spatial hierarchies. In: Chisholm M, Frey AE, Hagget P, editors. Regional Forecasting. London: Butterworths; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Woldenberg MJ, Horsfield K. Relation of branching angles to optimality for four cost principles. J Theor Biol. 1986;122:187–204. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(86)80081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]