Abstract

Study Objective

Antipsychotic polypharmacy—the use of more than one second-generation antipsychotic—has increased in children and adolescents and may be associated with increased adverse effects, nonadherence, and greater costs. Thus, we sought to examine the demographic and clinical characteristics of psychiatrically hospitalized children and adolescents who were prescribed antipsychotic polypharmacy and to identify predictors of this prescribing pattern.

Design

Retrospective medical record review.

Setting

Large, acute care, urban, children's hospital, inpatient psychiatric unit.

Patients

One thousand four hundred twenty-seven children and adolescents who were consecutively admitted and discharged between September 2010 and May 2011.

Measurements and Main Results

At discharge, 840 (58.9%) of the 1427 patients were prescribed one or more antipsychotics, 99.3% of whom received second-generation antipsychotics. Of these 840 patients, 724 (86.2%) were treated with antipsychotic monotherapy, and 116 (13.8%) were treated with antipsychotic polypharmacy. Positive correlations with antipsychotic polypharmacy were observed for placement or custody outside the biological family; a greater number of previous psychiatric admissions; longer hospitalizations; admission for violence/aggression or psychosis; and intellectual disability, psychotic, disruptive behavior, or developmental disorder diagnoses. Negative correlations with antipsychotic polypharmacy included admission for suicidal ideation/attempt or depression, and mood disorder diagnoses. Significant predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy included admission for violence or aggression (odds ratio [OR] 2.76 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.36-5.61]), greater number of previous admissions (OR 1.21 [95% CI 1.10-1.33]), and longer hospitalizations (OR 1.08 [95% CI 1.04-1.12]). In addition, diagnoses of intellectual disability (OR 2.62 [95% CI 1.52-4.52]), psychotic disorders (OR 5.60 [95% CI 2.29-13.68]), and developmental disorders (OR 3.18 [95% CI 1.78-5.65]) were predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy.

Conclusion

Certain youth may have a higher likelihood of being prescribed antipsychotic polypharmacy, which should prompt careful consideration of medication treatment options during inpatient hospitalization. Future examinations of the rationale for combining antipsychotics, along with the long-term safety, tolerability, and cost effectiveness of these therapies, in youth are urgently needed.

Keywords: psychiatric hospitalization, antipsychotic, polypharmacy, child and adolescent psychiatry

Inpatient psychiatric admissions have increased among children and adolescents over the past 2 decades, with hospitalization rates rising from 0.84% to 1.25% over this period.1 In parallel, the use of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in youth has dramatically increased.2-11 This rise in SGA prescribing likely relates to a myriad of factors, including an accumulating evidence base and United States Food and Drug Administration approval for the use of these medications in youth with mood, psychotic, and pervasive developmental disorders12-15 as well as off-label prescribing. However, despite the clinical benefits of these agents, children and adolescents may be more vulnerable to SGA-related adverse effects,16-21 including sedation, drug-induced movement disorders (e.g., dystonic reactions, akathisia), and metabolic abnormalities (e.g., weight gain, dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance).22 Moreover, adverse effects may also increase health care costs and adversely impact adherence and quality of life.

Recent data suggest that a significant population of children and adolescents are treated with more than one antipsychotic concomitantly (i.e., antipsychotic polypharmacy),23 with the majority of regimens including more than one SGA.24,25 However, to date, there are scant data on clinical benefit, safety, or cost-effectiveness of antipsychotic polypharmacy in youth.26,27 The knowledge gap remains, as current evidence is limited to small or uncontrolled studies in adults with psychotic disorders.27 These reports suggest that antipsychotic polypharmacy is associated with increased adverse effects and medical costs yet lacks evidence of clinical benefit, aside from clozapine augmentation in adults with treatment-resistant schizophrenia.26,27 This practice became such a concern that “patients discharged on multiple antipsychotic medication” and “patients discharged on multiple antipsychotic medications with appropriate justification” were among the seven 2010 Hospital-Based Inpatient Psychiatric Services (HBIPS) core measures,28 which remain in the 2013 Joint Commission National Quality Measures.29 Nonetheless, antipsychotic polypharmacy is an enduring clinical practice in adult populations.30,31 Data on the prevalence and predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy in youth are limited, as the extant data are extracted from studies of antipsychotics in children and adolescents designed to investigate other aims. In this regard, antipsychotic polypharmacy descriptions are primarily derived from studies that were designed to examine adverse effects and treatment duration,21 metabolic changes,32 use and prescribing practices,33,34 and SGA versus first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) dyskinesia risk.35

Although more than a dozen studies have examined antipsychotic treatment patterns between 1993 and 2008,23 few have evaluated antipsychotic polypharmacy. Moreover, only five studies have examined prescribing patterns in inpatient or residential settings21,32-35 and have reported the prevalence of antipsychotic polypharmacy as ranging from 2.9-27%; in these studies, correlates of antipsychotic polypharmacy were bipolar- or schizophrenia-spectrum disorder diagnoses, treatment with anxiolytics or hypnotics, and SGA plus SGA regimens; FGA plus SGA treatment was negatively correlated.23 Three studies used Medicaid data and reported that antipsychotic polypharmacy rates were 4.4-7.1% among youth, and correlates were male sex, older age (adolescent vs child), non-white race, autism, bipolar disorder, conduct disorder, psychotic disorders, and treatment with antidepressants and mood stabilizers; however, these studies—because of the data sources—have limited direct information related to specific clinical characteristics of the populations being studied.24,25,36

Higher rates of antipsychotic prescribing have been documented in children and adolescents with public versus private insurance.4-6,37,38 Moreover, among the Medicaid-insured, rates are higher in youth in foster care.5,25,39 Antipsychotic polypharmacy was also more likely, and occurred for longer durations, in Medicaid-insured youth in foster care.25 Knowledge on predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy in youth is largely limited to state Medicaid claims data in outpatients, which precludes the examination of payer (e.g., public vs private insurance) as a potential correlate. Importantly, findings from outpatient claims data may have significant limitations in that they may not be applicable to a general child and adolescent inpatient psychiatry setting, a level of care utilized by an increasing number of youth.1 Given the increasing prevalence of antipsychotic polypharmacy and concerns related to increased risks for nonadherence and adverse effects, as well as costs, it is critical to determine the characteristics of youth that increase their vulnerability to be treated with multiple antipsychotics. With these considerations in mind and to address this gap in knowledge, we examined factors potentially associated with increased risk of antipsychotic polypharmacy in a large, mixed-payer population, reviewing demographic and clinical characteristics of all children and adolescents (i.e., not limited to antipsychotic-treated patients) discharged from an inpatient psychiatric facility.

Data are scant regarding antipsychotic polypharmacy in pediatric patients, and there are no data regarding predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy in psychiatrically hospitalized youth.

Methods

In this retrospective analysis, medical records were reviewed from consecutively admitted patients who were discharged from the psychiatry service at a large, urban children's hospital between September 2010 and May 2011. If a patient had more than one admission, data from the last hospitalization during the study period were included in the analyses. Medical records reviewed included emergency department intake forms, admission notes, progress notes, and discharge summaries. Data extracted from medical records were reviewed by a board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrist (JRS). This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (Cincinnati, OH).

All treating physicians were fellowship-trained, board-certified, or board-eligible child and adolescent psychiatrists, and all diagnoses were made by the treating psychiatrists in accordance with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)40 criteria. Diagnoses were documented in the narrative medical record (e.g., discharge summary, progress note, admission note). Diagnoses were categorized into the following groups of disorders: attention-deficit–hyperactivity (ADHD), eating, mood, anxiety, psychotic, disruptive behavior, substance use, developmental, and intellectual disability. In addition to extracting all psychiatric diagnoses recorded by the treating psychiatrist, demographic and clinical data collected included sex, age, race, ethnicity, insurance/payer, custody and placement, reason for admission (e.g., chief complaint), medications, and trauma/abuse histories. Additionally, the medical center's formulary did not exclude any antipsychotics, thus limiting any significant formulary-related effects that may have been present in some previous studies that relied on insurance databases. Last, antipsychotics included all FGAs and SGAs and were only considered part of the regimen if prescribed on a scheduled basis (i.e., not for as-needed [p.r.n.] administration).

Statistical Analysis

Patients were grouped by zero, one, or more than one antipsychotic at discharge. Analyses compared data from patients discharged on antipsychotic monotherapy and patients discharged on antipsychotic polypharmacy. Clinical and demographic variables were compared between groups by using Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and Student t tests for continuous variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify significant associations of antipsychotic polypharmacy and demographic and clinical factors that differed significantly between the antipsychotic monotherapy and polypharmacy groups: placement or custody outside the biological family, previous admissions, length of stay, reasons for admission, and diagnoses. Additionally, as a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and psychosis reason for admission were highly correlated, a new variable (psychotic disorder diagnosis or psychosis reason for admission) was created, and only this variable was included in the multivariate model. However, a post hoc analysis with the separated variables did not affect any of the significant findings.

Results

Of 1433 consecutively admitted patients who were discharged during the study period, six patients who had a length of hospitalization less than 1 day were excluded; thus, 1427 patients were included in the analyses. Of these patients, 840 (58.9%) were prescribed one or more antipsychotics at discharge, 99.3% of whom received SGAs. Of these 840 patients, 724 (86.2%) were discharged with antipsychotic monotherapy, and 116 (13.8%) were discharged with antipsychotic polypharmacy. Demographics and clinical characteristics of study patients are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the 1427 Study Patients.

| Characteristic | No antipsychotics (n=587) | Antipsychotic monotherapy (n=724) | Antipsychotic polypharmacy (n=116) | p Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 314 (53) | 270 (37) | 39 (34) | 0.45 |

| Age, yrs (mean ± SD) | 14.2 ± 3.3 | 13.0 ± 3.7 | 13.4 ± 3.5 | 0.19 |

| Race (n=1400) | 0.86 | |||

| (n=583) | (n=705) | (n=112) | ||

| White | 414 (71) | 460 (65) | 73 (65) | |

| Black | 139 (24) | 215 (30) | 33 (29) | |

| Other | 30 (5) | 30 (4) | 6 (5) | |

| Ethnicity (n=1416) | 0.63 | |||

| (n=586) | (n=719) | (n=111) | ||

| Hispanic | 16 (3) | 8 (1) | 2 (2) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 570 (97) | 711 (99) | 109 (98) | |

| (n=569) | (n=667) | (n=102) | ||

| Placement with family (n=1338) | 546 (96) | 612 (92) | 81 (79) | <0.001 |

| Insurance type (n=1386) | 0.42 | |||

| (n=569) | (n=707) | (n=110) | ||

| Public | 341 (60) | 494 (70) | 81 (74) | |

| Private | 228 (40) | 213 (30) | 29 (26) | |

Data are no. (%) of patients unless otherwise specified.

Antipsychotic monotherapy group vs polypharmacy group (χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables and t test for continuous variables).

Table 2. Clinical Characteristics of the 1427 Study Patients.

| Characteristic | No antipsychotics (n=587) |

Antipsychotic monotherapy (n=724) |

Antipsychotic polypharmacy (n=116) |

p Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of previous psychiatry admissions (mean ± SD) (n=1388) | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 1.9 | 2.9 ± 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Length of stay, days (mean ± SD) | 5.6 ± 3.0 | 8.3 ± 4.9 | 12.5 ± 9.4 | <0.001 |

| Trauma/abuse history | 234 (40) | 333 (46) | 53 (46) | 0.95 |

| Reasons for admission | ||||

| Violence/aggression | 156 (27) | 380 (52) | 86 (74) | <0.001 |

| Suicidal ideation/attempt | 412 (70) | 314 (43) | 30 (26) | <0.001 |

| Psychosis | 17 (3) | 64 (9) | 21 (18) | 0.002 |

| Depression | 119 (20) | 56 (8) | 2 (2) | 0.018 |

| Homicidal ideation/attempt | 42 (7) | 82 (11) | 10 (9) | 0.39 |

| Self-injurious behavior | 18 (3) | 19 (3) | 6 (5) | 0.14 |

| Impulsive behavior | 21 (4) | 29 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.11 |

| Diagnoses | ||||

| Developmental disorder | 21 (4) | 84 (12) | 43 (37) | <0.001 |

| Intellectual disability | 35 (6) | 110 (15) | 56 (48) | <0.001 |

| Mood disorder | 457 (78) | 485 (67) | 64 (55) | 0.013 |

| Psychotic disorder | 7 (1) | 46 (6) | 17 (15) | 0.002 |

| Disruptive behavior disorder | 135 (23) | 304 (42) | 61 (53) | 0.032 |

| Anxiety disorder | 147 (25) | 192 (27) | 24 (21) | 0.18 |

| Substance use disorder | 74 (13) | 49 (7) | 5 (4) | 0.32 |

| Attention-deficit–hyperactivity disorder | 129 (22) | 264 (36) | 37 (32) | 0.34 |

| Eating disorder | 14 (2) | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | >0.99 |

Data are no. (%) of patients unless otherwise specified.

Antipsychotic monotherapy group vs polypharmacy group (χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables and t test for continuous variables).

Antipsychotics Prescribed at Discharge

Among patients receiving antipsychotic monotherapy and polypharmacy, the most frequently prescribed antipsychotics at discharge were quetiapine (21.4% of monotherapy, 59.5% of polypharmacy), aripiprazole (32.2%, 49.1%), and risperidone (35.6%, 38.9%). Treatment with olanzapine, ziprasidone, paliperidone, and clozapine was less frequent, with each prescribed in less than 20% of discharged patients receiving antipsychotic therapy. Among the FGAs, haloperidol and perphenazine were the only two agents prescribed as monotherapies, in less than 1% of all monotherapy recipients. Haloperidol, perphenazine, chlorpromazine, thioridazine, fluphenazine, and pimozide were present in combination regimens, and each was prescribed in less than 10% of polypharmacy recipients. Nearly all (99% of monotherapy, 100% of polypharmacy) patients received SGAs. Antipsychotic combinations by class were SGA plus SGA (81%), SGA plus FGA (16%), and SGA plus SGA plus FGA (3%); no patients were treated with more than one FGA, and no patients received more than two SGAs. The most frequent combinations were aripiprazole plus quetiapine (22%) and risperidone plus quetiapine (20%), followed by aripiprazole plus risperidone (11%) and olanzapine plus quetiapine (6%). There were 10 additional SGA plus SGA combinations, 10 SGA plus FGA combinations, and four SGA plus SGA plus FGA combinations, each of which was present in 5% or less of the patients (Table 3).

Table 3. Antipsychotic Combinations Prescribed for the 116 Patients Receiving Antipsychotic Polypharmacy.

| Antipsychotic Combination | No. (%) of Patients |

|---|---|

| Aripiprazole + Quetiapine | 26 (22.4) |

| Aripiprazole + Risperidone | 13 (11.2) |

| Aripiprazole + Olanzapine | 5 (4.3) |

| Aripiprazole + Ziprasidone | 5 (4.3) |

| Aripiprazole + Haloperidol | 3 (2.6) |

| Aripiprazole + Paliperidone | 2 (1.7) |

| Aripiprazole + Chlorpromazine | 1 (0.9) |

| Aripiprazole + Thioridazine | 1 (0.9) |

| Aripiprazole + Pimozide + Quetiapine | 1 (0.9) |

| Risperidone + Quetiapine | 23 (19.8) |

| Risperidone + Perphenazine | 2 (1.7) |

| Risperidone + Ziprasidone | 2 (1.7) |

| Risperidone + Chlorpromazine | 1 (0.9) |

| Risperidone + Clozapine | 1 (0.9) |

| Risperidone + Olanzapine | 1 (0.9) |

| Risperidone + Thioridazine | 1 (0.9) |

| Risperidone + Haloperidol + Quetiapine | 1 (0.9) |

| Olanzapine + Quetiapine | 7 (6.0) |

| Olanzapine + Ziprasidone | 3 (2.6) |

| Olanzapine + Perphenazine | 2 (1.7) |

| Olanzapine + Chlorpromazine | 1 (0.9) |

| Olanzapine + Haloperidol | 1 (0.9) |

| Olanzapine + Clozapine + Haloperidol | 1 (0.9) |

| Quetiapine + Haloperidol | 5 (4.3) |

| Quetiapine + Ziprasidone | 3 (2.6) |

| Quetiapine + Paliperidone | 2 (1.7) |

| Quetiapine + Fluphenazine + Olanzapine | 1 (0.9) |

| Ziprasidone + Paliperidone | 1 (0.9) |

Characteristics of Inpatients Discharged with Antipsychotic Medications

Results from univariate analyses, comparing characteristics of patients discharged on antipsychotic monotherapy and polypharmacy, are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Age, sex, race, ethnicity, and payer type did not differ significantly between the two groups. Positive correlations with antipsychotic polypharmacy were observed for placement or custody outside the biological family; a greater number of previous psychiatric admissions; longer hospitalizations; admission for violence/aggression or psychosis; and intellectual disability, psychotic, disruptive behavior, or developmental disorder diagnoses. Negative correlations with antipsychotic polypharmacy included admission for suicidal ideation/attempt or depression, and mood disorder diagnoses. Factors with significant associations were subsequently tested in multivariate logistic regression.

Predictors of Antipsychotic Polypharmacy

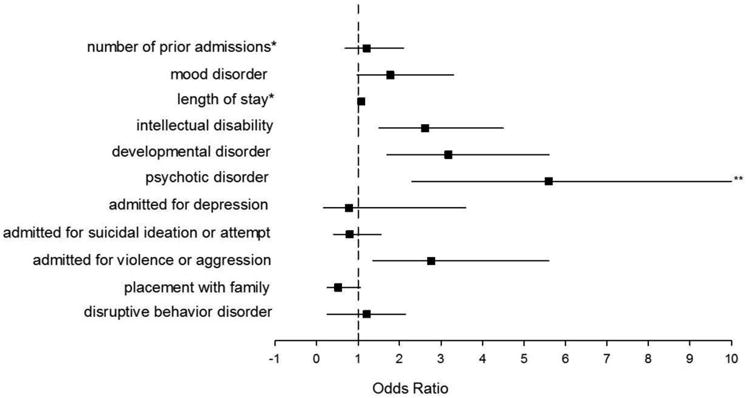

Multivariate logistic regression results indicated several significant predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy at discharge from inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for this model was 0.83. Predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy included admission for violence or aggression (odds ratio [OR] 2.76 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.36-5.61], p=0.005), greater number of previous admissions (OR 1.21 [95% CI 1.10-1.33], p<0.001), and longer hospitalizations (OR 1.08 [95% CI 1.04-1.12], p<0.001). In addition, diagnoses of intellectual disability (OR 2.62 [95% CI 1.52-4.52], p<0.001), psychotic disorders (OR 5.60 [95% CI 2.29-13.68], p<0.001), and developmental disorders (OR 3.18 [95% CI 1.78-5.65], p<0.001) were predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy at discharge from inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. The odds ratios for antipsychotic polypharmacy, in association with clinical and demographic factors, were determined by multivariate logistic regression. Horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals. *Odds ratios for number of prior admissions and length of stay correspond with a one-unit (e.g., 1 day or 1 hospitalization) increase in the variable; **Truncated (confidence interval 2.29-13.68).

Discussion

More than half of youth (58.9%) admitted were discharged with at least one antipsychotic. Additionally, 8.1% of all inpatients and 13.8% of antipsychotic-treated inpatients were discharged on antipsychotic polypharmacy. As expected, and consistent with other studies,24,25 the majority (99.3%) of youth receiving antipsychotics were treated with SGAs. Among antipsychotic-treated patients, the 13.8% rate of antipsychotic polypharmacy was within the range of rates reported in other studies in both inpatient/residential (2.9-27%)21,32-35 and undescribed, mixed, and outpatient (0.08-15.5%)24,25,36,41-47 settings. Further, three of the four most frequent combinations in this study were also found to be among the four most common combinations in the largest pediatric study,24 and quetiapine and/or aripiprazole was present in each of these regimens. Additional antipsychotic combinations are presented in Table 3.

Several concerns related to the use of psychotropic medications in the treatment of publically insured youth have been raised in reports from the United States Government Accountability Office and Health and Human Services.37,48 Among these concerns are the number of youth treated with SGAs (monotherapy and polypharmacy) and insufficient oversight for prescribing and monitoring. Additionally, it has been recently established that having public insurance predicts increased SGA treatment among youth,4-6,37,38 a finding that was consistent with our data. Regarding antipsychotic polypharmacy, our study is the first, to our knowledge, to analyze payer source in an inpatient setting, and although more patients treated with polypharmacy had public insurance than those with monotherapy, this difference was not statistically significant. Our study employed a much smaller sample than Medicaid-based reports and focused only on inpatients; however, these data raise the possibility that once youth are treated with one SGA, public insurance is not a significant risk factor for receiving combination antipsychotic therapy, and other risk factors may be shared among antipsychotic-treated youth, whether privately or publically insured. Thus, it is important to identify patients at increased risk for receiving these treatments to better understand their characteristics and to consider standards of care for their evaluation and management, irrespective of payer status.

We observed that longer lengths of stay were associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy; however, there are several possible explanations for this finding. First, it is plausible these patients were more severely ill, and, second, it is possible that rates of treatment resistance may have been higher in this group. If true, this would account for alternate treatment strategies, including antipsychotic polypharmacy, and may have also necessitated the longer hospitalizations. This would be consistent with the additional findings of increased numbers of previous psychiatric hospitalizations among antipsychotic polypharmacy recipients. Conversely, healthcare providers may experience pressure to minimize duration of hospitalization and may be more prone to add additional medications during extended hospitalizations, a finding consistent with the observation that increased costs may contribute more to length of stay than psychiatric illness.49,50 As well, some patients may lack outpatient care benefits or access to nonpharmacologic treatments, also leading prescribers to use other pharmacologic strategies, such as antipsychotic polypharmacy. The relationships among payer, length of stay, and access to care, as well as rehospitalizations and long-term medical costs warrant additional research. Alternately, these patients may have longer hospitalizations because they are treated with multiple antipsychotics.

In our study, developmental disorders and intellectual disability were predictive of antipsychotic polypharmacy at discharge, an association not previously identified in the literature. Intellectual disability is common in developmental disorders51 and may—in some instances—be associated with target symptoms of aggression in hospitalized youth.52-54 Aggression is a common clinical symptom for hospitalized children with disruptive behavior disorders, specifically conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder,40 diagnoses present in 39.5% of children and 25.8% of adolescents treated with antipsychotic polypharmacy in other studies.23 Disruptive behavior disorders were also prevalent in our study but were not a significant predictor of polypharmacy. A large proportion (52.6%) of youth with intellectual disability and developmental disorders in our study were admitted for violence or aggression. This shared clinical presentation among disruptive behavior disorders, developmental disorders, and intellectual disability suggests that a potential rationale for antipsychotic polypharmacy treatment is to mitigate aggression. Limited data exist on the safety and effectiveness of antipsychotics in youth with intellectual disabilities, with most reports describing treatment of irritability or aggressive behavior,55 with inconsistent findings.56,57 Clinical experience and guidelines58 suggest that the association between intellectual/developmental disability and SGA polypharmacy is clinically relevant, as patients with intellectual disability respond differently and may be more sensitive to adverse effects.

In this retrospective evaluation, the rationale for clinical decisions regarding antipsychotic coprescription was not routinely documented; however, there are a number of potential explanations for antipsychotic polypharmacy. First, it is plausible that patients were being transitioned from one antipsychotic to another, with the process beginning during hospitalization and not yet complete at discharge. Second, patients may have been unable to tolerate higher doses of a single antipsychotic, prompting combination therapy with an agent possessing a different adverse-effect profile. It remains possible that choice of antipsychotic combination may have been based on distinct pharmacologic properties such as receptor binding (e.g., low potency + high potency) or adverse-effect profiles. Interestingly, quetiapine and aripiprazole were each present in 32% of all combinations. Quetiapine may have been used to treat dysomnias, based on its sedating, antihistaminergic profile, which may have been of benefit in patients with mania or psychotic agitation; however, this cannot be determined from these data. Recently, Constantine and colleagues postulated that aripiprazole may have been prescribed due to its perceived lower metabolic liability compared with other agents available at the time of the study.24 Indeed, this rationale may underlie prescribing decisions, as 3 years later, we also found aripiprazole among the most commonly prescribed combinations. Recent data demonstrate a more favorable metabolic profile for aripiprazole,22 which may guide antipsychotic prescribing prior to or during hospitalization. The prevalence of antipsychotic polypharmacy is high, particularly the concomitant use of quetiapine and aripiprazole with other SGAs. Given the frequency of antipsychotic polypharmacy and diverse pharmacologic profiles among SGAs, more research is urgently needed to guide therapy to optimize the risks and benefits of SGA treatment, especially when used in combination.

This is the first study to examine antipsychotic polypharmacy in a sample of psychiatrically hospitalized youth. Although we examined a very well–characterized sample, these data were derived from a single site, and, as with any single-site study, results will require replication to confirm generalizability. Moreover, there are inherent limitations associated with the retrospective design; as such, the results of this study should be considered within the context of the study's limitations. Comprehensive prior psychiatric or medication histories for the patients included in our study were unavailable, and thus the rationale for a specific prescribing pattern with regard to previous treatment failures or intolerabilities could not be ascertained. In addition, the retrospective nature does not permit exact knowledge of the indication for antipsychotic therapy. Again, rationales for combining antipsychotics were not always clearly documented in the medical record, yet the same inability to ascertain rationale (for monotherapy and polypharmacy) is present in large Medicaid claims data and most other studies. Multiple outpatient claims for two or more antipsychotics over several months may strongly suggest enduring co-therapy, whereas coprescription on discharge from inpatient psychiatric hospitalization may represent transition from one medication to another, potentially overestimating rates of polypharmacy. Nonetheless, this is the first study to represent a real-world inpatient setting, where information is critically needed, in light of increased rates of pediatric psychiatric hospitalization and antipsychotic polypharmacy, despite the dearth of evidence in youth.

Conclusion

Predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy in youth at discharge from psychiatric hospitalizations were admission for violence or aggression, diagnoses of intellectual disability, psychotic disorders, or developmental disorders, a greater number of previous admissions, and longer hospitalization. These patients may be at increased risk for treatment with multiple antipsychotics, warranting careful attention to clinical benefit, adverse effects, adherence, and costs. There is a critical need for prospective, possibly naturalistic, trials to examine the longitudinal course of patients treated with antipsychotic polypharmacy and to characterize the efficacy and tolerability of this practice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott Schappacher (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Division of Pharmacy) for his assistance and helpful discussions related to antipsychotic polypharmacy at our institution.

Dr. Strawn has received research support from the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Eli Lilly, Shire, Lundbeck, and Forest Research Laboratories. Dr. Keeshin has received research support from the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and from the Doris Duke Foundation. Dr. DelBello has served as a consultant, adviser, or speaker for Otsuka, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Schering-Plough, Lundbeck, Sunovian, and Pfizer. She has also received research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, as well as AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Janssen, Pfizer, Otsuka, Sumitomo, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Schering Plough, and Merck. Although given the nature of this study, these relationships are not believed to represent conflicts of interest, they are provided in the spirit of full disclosure.

Support was received from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; grant 8 UL1 TR000077-05). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Dr. Saldaña, Ms. Wehry, and Mr. Blom report no biomedical conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Blader JC. Acute inpatient care for psychiatric disorders in the United States, 1996 through 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 Dec;68(12):1276–1283. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu SM, et al. National trends in the office-based treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with antipsychotics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012 Dec 1;69(12):1247–1256. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C, et al. Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;49(1):13–23. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel NC, Crismon ML, Hoagwood K, et al. Trends in the use of typical and atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;44(6):548–556. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000157543.74509.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crystal S, Olfson M, Huang C, et al. Broadened use of atypical antipsychotics: safety, effectiveness, and policy challenges. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009 Sep-Oct;28(5):w770–781. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L, et al. National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Jun;63(6):679–685. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matone M, Localio R, Huang YS, et al. The relationship between mental health diagnosis and treatment with second-generation antipsychotics over time: a national study of U.S. Medicaid-enrolled children. Health services research. 2012 Oct;47(5):1836–1860. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zito JM, Burcu M, Ibe A, et al. Antipsychotic use by medicaid-insured youths: impact of eligibility and psychiatric diagnosis across a decade. Psychiatr Serv. 2013 Mar 1;64(3):223–229. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alessi-Severini S, Biscontri RG, Collins DM, et al. Ten years of antipsychotic prescribing to children: a Canadian population-based study. Can J Psychiatry. 2012 Jan;57(1):52–58. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rani F, Murray ML, Byrne PJ, et al. Epidemiologic features of antipsychotic prescribing to children and adolescents in primary care in the United Kingdom. Pediatrics. 2008 May;121(5):1002–1009. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Comer JS, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996-2007. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Oct;49(10):1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kowatch RA, Fristad M, Birmaher B, et al. Treatment guidelines for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 Mar;44(3):213–235. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myers SM, Johnson CP. Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120(5):1162–1182. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pappadopulos E, Macintyre Ii JC, Crismon ML, et al. Treatment recommendations for the use of antipsychotics for aggressive youth (TRAAY). Part II. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003 Feb;42(2):145–161. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young CM, Findling RL. Pharmacologic treatment of adolescent and child schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004 Jan;4(1):53–60. doi: 10.1586/14737175.4.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Correll CU. Antipsychotic use in children and adolescents: minimizing adverse effects to maximize outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008 Jan;47(1):9–20. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815b5cb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McConville BJ, Sorter MT. Treatment challenges and safety considerations for antipsychotic use in children and adolescents with psychoses. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 6):20–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(Suppl 1):1–93. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200519001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Correll CU. Weight gain and metabolic effects of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics in pediatric bipolar disorder: a systematic review and pooled analysis of short-term trials. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Jun;46(6):687–700. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318040b25f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Correll CU, Carlson HE. Endocrine and metabolic adverse effects of psychotropic medications in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006 Jul;45(7):771–791. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000220851.94392.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laita P, Cifuentes A, Doll A, et al. Antipsychotic-related abnormal involuntary movements and metabolic and endocrine side effects in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007 Aug;17(4):487–502. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, et al. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009 Oct 28;302(16):1765–1773. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toteja N, Gallego JA, Saito E, et al. Prevalence and correlates of antipsychotic polypharmacy in children and adolescents receiving antipsychotic treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013 May 14;:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712001320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Constantine RJ, Boaz T, Tandon R. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in the treatment of children and adolescents in the fee-for-service component of a large state Medicaid program. Clin Ther. 2010 May;32(5):949–959. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dosreis S, Yoon Y, Rubin DM, et al. Antipsychotic treatment among youth in foster care. Pediatrics. 2011 Dec;128(6):e1459–1466. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallego JA, Nielsen J, De Hert M, et al. Safety and tolerability of antipsychotic polypharmacy. Expert opinion on drug safety. 2012 Jul;11(4):527–542. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2012.683523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lochmann van Bennekom MW, Gijsman HJ, Zitman FG. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in psychotic disorders: a critical review of neurobiology, efficacy, tolerability and cost effectiveness. J Psychopharmacol. 2013 Apr;27(4):327–336. doi: 10.1177/0269881113477709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hospital Based Inpatient Psychiatric Services. Specifications Manual for Joint Commission National Quality Measures (v2010A) 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hospital Based Inpatient Psychiatric Services. Specifications Manual for Joint Commission National Quality Measures (v2013A1) 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Correll CU, Gallego JA. Antipsychotic polypharmacy: a comprehensive evaluation of relevant correlates of a long-standing clinical practice. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2012 Sep;35(3):661–681. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallego JA, Bonetti J, Zhang J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of antipsychotic polypharmacy: a systematic review and meta-regression of global and regional trends from the 1970s to 2009. Schizophrenia research. 2012 Jun;138(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel NC, Hariparsad M, Matias-Akthar M, et al. Body mass indexes and lipid profiles in hospitalized children and adolescents exposed to atypical antipsychotics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007 Jun;17(3):303–311. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly DL, Love RC, MacKowick M, et al. Atypical antipsychotic use in a state hospital inpatient adolescent population. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004 Spring;14(1):75–85. doi: 10.1089/104454604773840517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pappadopulos E, Jensen PS, Schur SB, et al. “Real world” atypical antipsychotic prescribing practices in public child and adolescent inpatient settings. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):111–121. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Connor DF, Fletcher KE, Wood JS. Neuroleptic-related dyskinesias in children and adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 Dec;62(12):967–974. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrato EH, Dodd S, Oderda G, et al. Prevalence, utilization patterns, and predictors of antipsychotic polypharmacy: experience in a multistate Medicaid population, 1998-2003. Clin Ther. 2007 Jan;29(1):183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CHILDREN'S MENTAL HEALTH: Concerns Remain about Appropriate Services for Children in Medicaid and Foster Care. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curtis LH, Masselink LE, Ostbye T, et al. Prevalence of atypical antipsychotic drug use among commercially insured youths in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005 Apr;159(4):362–366. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.4.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Antipsychotic Medication Use in Medicaid Children and Adolescents: Report and Resource Guide from a 16-State Study. Rutgers, New Jersey: Medicaid Medication Directors Learning Network, Rutgers Center for Education and Research on Mental Health Therapeutics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th., text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castro-Fornieles J, Parellada M, Soutullo CA, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in child and adolescent first-episode psychosis: a longitudinal naturalistic approach. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2008 Aug;18(4):327–336. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dean AJ, McDermott BM, Marshall RT. Psychotropic medication utilization in a child and adolescent mental health service. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006 Jun;16(3):273–285. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong IS, Bishop JR. Anticholinergic use in children and adolescents after initiation of antipsychotic therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2010 Jul-Aug;44(7-8):1171–1180. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jerrell JM, McIntyre RS. Adverse events in children and adolescents treated with antipsychotic medications. Human psychopharmacology. 2008 Jun;23(4):283–290. doi: 10.1002/hup.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kogut SJ, Yam F, Dufresne R. Prescribing of antipsychotic medication in a medicaid population: use of polytherapy and off-label dosages. Journal of managed care pharmacy : JMCP. 2005 Jan-Feb;11(1):17–24. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simeon J, Milin R, Walker S. A retrospective chart review of risperidone use in treatment-resistant children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 2002 Feb;26(2):267–275. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wonodi I, Reeves G, Carmichael D, et al. Tardive dyskinesia in children treated with atypical antipsychotic medications. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2007 Sep 15;22(12):1777–1782. doi: 10.1002/mds.21618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.FOSTER CHILDREN: HHS Guidance Could Help States Improve Oversight of Psychotropic Prescriptions. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pottick KJ, McAlpine DD, Andelman RB. Changing patterns of psychiatric inpatient care for children and adolescents in general hospitals, 1988-1995. Am J Psychiatry. 2000 Aug;157(8):1267–1273. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bodner E, Sarel A, Gillath O, et al. The relationship between type of insurance, time period and length of stay in psychiatric hospitals: the Israeli case. The Israel journal of psychiatry and related sciences. 2010;47(4):284–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fombonne E. Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatric research. 2009 Jun;65(6):591–598. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819e7203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aman MG. Assessing Psychopathology and Behavior Problems in Persons with Mental Retardation: A Review of Available Instruments. Department Human Services publication (ADM); 1991. pp. 91–1712. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benson BA. Behavior disorders and mental retardation: associations with age, sex, and level of functioning in an outpatient clinic sample. Applied research in mental retardation. 1985;6(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0270-3092(85)80023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reiss S. Prevalence of dual diagnosis in community-based day programs in the Chicago metropolitan area. American journal of mental retardation : AJMR. 1990 May;94(6):578–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pringsheim T, Gorman D. Second-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of disruptive behaviour disorders in children: a systematic review. Can J Psychiatry. 2012 Dec;57(12):722–727. doi: 10.1177/070674371205701203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruedrich SL, Swales TP, Rossvanes C, et al. Atypical antipsychotic medication improves aggression, but not self-injurious behaviour, in adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of intellectual disability research : JIDR. 2008 Feb;52(Pt 2):132–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tyrer P, Oliver-Africano PC, Ahmed Z, et al. Risperidone, haloperidol, and placebo in the treatment of aggressive challenging behaviour in patients with intellectual disability: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008 Jan 5;371(9606):57–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guideline 4: Medication Treatment: General Principles. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2000 May 01;105(3):178–181. 2000. [Google Scholar]