Abstract

If couples can maintain normalcy and quality in their relationship during the cancer experience, they may experience greater relational intimacy. Cancer-specific relationship awareness, which is an attitude defined as partners focusing on the relationship and thinking about how they might maintain normalcy and cope with cancer as a couple or “team”, is one factor that may help couples achieve this goal. The main aim of this study was to evaluate the associations between cancer-specific relationship awareness, cancer-specific communication (i.e., talking about cancer’s impact on the relationship, disclosure, and responsiveness to partner disclosure), and relationship intimacy and evaluate whether relationship communication mediated the association between relationship awareness and intimacy. Two hundred fifty four women diagnosed with early stage breast cancer and their partners completed measures of cancer-specific relationship awareness, relationship talk, self-and perceived partner disclosure, perceived partner responsiveness, and relationship intimacy. Results indicated that patients and spouses who were higher in cancer-specific relationship awareness engaged in more relationship talk, reported higher levels of self-disclosure, and perceived that their partner disclosed more. Their partners reported that they were more responsive to disclosures. Relationship talk and perceived partner responsiveness mediated the association between cancer–specific relationship awareness and intimacy. Helping couples consider ways they can maintain normalcy and quality during the cancer experience and framing coping with cancer as a “team” effort may facilitate better communication and ultimately enhance relationship intimacy.

Keywords: Relationship awareness, relationship communication, relationship talk, intimacy, breast cancer, couples

Introduction

The diagnosis and treatment of early stage breast cancer is challenging for both patient and spouse. Patients deal with the emotional consequences of being diagnosed with a life-threatening illness, cope with both short- (e.g., nausea from chemotherapy, difficult surgical recovery; Fernandez-Ortega et al., 2012; McNeely et al., 2012) and long- term impairments (fatigue, lymphedema, memory deficits, changes in bodily appearance and body image, sexual functioning concerns; Minton, Stone, Richardson, Sharpe, & Hotopf, 2008; Paskett, Dean, Oliveri, & Harrop, 2012; Von Ah, Habermann, Carpenter, & Schneider, 2012; Weber & Solomon, 2008; Yeo et al., 2004), manage worries about a future recurrence (Yeo et al., 2004), and manage family roles and responsibilities (Weber & Solomon, 2008). Partners assist patients with negotiating medical care (Kim, Kashy, Spillers, & Evans, 2010), deal with changes in their sexual relationship (Yeo, et al., 2004), and cope with the stress associated with providing support to a sick spouse and concerns about how the ill partner is coping (Gotay, 1984; Fletcher, Lewis, & Haberman, 2010). Partners also manage concerns about the well-being of children and family (Fletcher et al., 2010), deal with worries about their own well being and mortality (Fletcher et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2010; Zahlis & Lewis, 2010), and manage worries about cancer recurrence and about the possible loss of their spouse (Gotay, 1984; Zahlis & Shands, 1993). Even after treatment is completed, patients integrate old and new identities (Solomon, Weber, & Steuber, 2010) couples negotiate the transition back to “normal” life, consider re-prioritizing life goals, and manage any healthy lifestyle changes that they wish to undertake (Kim et al, 2010). These experiences can take an emotional toll on patient and partner. Between 7% and 46% of women with early stage breast cancer report clinically-significant levels of depressive symptoms within the first six months of diagnosis and between 32% and 45% of women report clinically significant levels of anxiety (Gallagher, Parle, & Cairns, 2002; Omne-Ponten, Holmberg, Burns, Adami, & Bergstrom, 1992). While few studies have documented clinical levels of distress among husbands or partners, research suggests that partners report anxiety and depressive symptoms as well (Northouse, Templin, Mood, & Oberst, 1998).

The marital relationship can be a source of emotional and practical support for both patient and partner during the cancer experience and help them cope with these stressors (Giese-Davis, Hermanson, Koopman, Weibel, & Spiegel, 2000; Jenewein et al., 2007; Pistrang & Barker, 1998). Therefore, maintaining the quality of this relationship is an important goal. One key component of relationship quality is intimacy which we defined as the perceived emotional closeness of the relationship. Research suggests that intimacy is related to couples’ relationship satisfaction (Greeff & Malherbe, 2001) and to the well-being of marital partners (Prager & Buhrmester, 1998). Relationship intimacy can serve as a psychological buffer for the effects of severe life stressors such as loss of a child or combat on psychological problems (Lang, Gottlieb, & Amsel, 1996; Zerach, Anat, Solomon, & Heruti, 2010). Greater marital intimacy is associated with lower salivary cortisol levels and serves as a buffer for the physiological effects of life stress (Ditzen et al., 2008). Given the significance of intimacy in relationship quality, it is important to understand the processes through which couples maintain intimacy in the face of cancer. We will evaluate these processes in this study.

Theoretical Rationale

Our work merges constructs from two interpersonal relationship theories, the relationship awareness theory (Acitelli, 1988, 1992, 1993; Acitelli & Duck, 1987; Cate, Koval, Lloyd, & Wilson, 1995; Canary & Stafford, 1994; Guerrero, Eloy, & Wabnick, 1993), and the Interpersonal Process Model of Intimacy (IPM; Reis & Patrick, 1996; Reis & Shaver, 1988). According to relationship awareness theory, one way that couples maintain intimacy when one partner develops cancer may be through the way they incorporate cancer into their relationship. It is widely thought that couples develop ways of thinking about their relationship which help maintain normalcy and sustain quality of their relationship during both the challenges of everyday life (Olson, 2000) and during stressful experiences (Canary & Stafford, 1994; Guerrero et al., 1993). These attitudes can promote other positive relationship attitudes (e.g., liking the person), can motivate partners to engage in pro-relationship behaviors (e.g., expressions of caring; Canary, Stafford, & Semic, 2002), and may also prevent relationships from decaying (Dindia & Baxter, 1987). Relationship awareness is one hypothesized set of cognitions that help maintain normalcy, intimacy, and quality of relationships (Acitelli, 1988, 1992, 1993; Acitelli & Duck, 1987; Cate et al., 1995). Relationship awareness is defined as a partner focusing on his/her relationship or on a relationship interaction pattern, thinking about his/her relationship, and adopting a relationship perspective on life experiences (Acitelli, 1992; Cate et al., 1995; Acitelli, Rogers, & Knee, 1999). Among physically healthy couples, relationship awareness is associated with higher levels of marital happiness and commitment (Fletcher et al., 1987). However, little is known about the role of relationship awareness in how couples maintain relationship quality during the cancer experience. An additional relatively unexplored area of study is the role of cancer-specific aspects of relationship awareness. That is, assessing the degree to which partners consider how cancer impacts their relationship and the degree to which partners view the cancer in relational rather than individual terms (Acitelli & Badr, 2005).

Although it is possible that relationship awareness directly facilitates greater relationship intimacy, it is more likely that the effects of relationship awareness (or any cognition) on perceptions of relationship intimacy are due to the behavioral manifestations of that awareness. One likely manifestation of relationship awareness is the degree and type of communication with one’s partner. Indeed, research evaluating attitudinal factors including relationship beliefs (Metts & Cupach, 1990; Uebelacker & Whisman, 2005) and expectations (Foran & Slep, 2007; Vanzetti & Notarias, 1991) suggest that they are associated with relationship communication. “Relationship talk” has been hypothesized as the most common manifestation of relationship awareness (Acitelli, 1988) and a proposed reason why awareness is associated with relationship outcomes (Acitelli, 2002). Relationship talk involves talking about one’s relationship and/or talking in relational terms about how life experiences impact the relationship (Acitelli, 1988; Goldsmith & Baxter, 1996). Relationship talk is associated with global measures of marital happiness and pro-relationship behaviors such as higher levels of adaptive conflict management (Bernal & Baker, 1979) and higher levels of marital support (Badr, Acitelli, Duck, & Carl, 2001). The limited research conducted to date has suggested that relationship talk is associated with individual and relationship outcomes among couples coping with illness. Badr and Acitelli (2005) compared couples in which one spouse was ill with couples in which both partners were healthy and found that relationship talk was more strongly associated with marital satisfaction among couples with an ill spouse than among healthy couples. Badr and Taylor (2008) studied the association between relationship talk and psychological distress among couples coping with lung cancer and found that patients and partners who reported more frequent discussions about their relationship reported less distress and greater marital adjustment over a six month period following the diagnosis and initial treatment of lung cancer.

Relationship talk may not be the only way that relationship awareness is manifested within a relationship. It is also possible that relationship awareness facilitates other communication behaviors such as self-disclosure about cancer-related concerns and being more responsive to one’s partner’s disclosures about cancer-related concerns. Disclosure and responsiveness are key facilitators of intimacy as proposed by the IPM. The IPM proposes that relationship intimacy is a process whereby one person expresses important self-relevant information and feelings to another and, as the result of the other person’s responsivity, comes to feel emotionally close with his or her partner (Reis & Patrick, 1996; Reis & Shaver, 1988). We have illustrated the importance of self-disclosure and perceived partner responsiveness in relationship intimacy among couples coping with breast cancer (Manne & Badr, 2008; Manne, Ostroff, Winkel, Grana, & Fox, 2005). In the present paper, we extend this previous work to include relationship awareness as an attitudinal variable that predicts self-disclosure and responsivity as well as ultimately predicting relationship intimacy. If our work supports the role of relationship awareness as a predictor of relationship communication, and, ultimately, of intimacy, this information may enhance the efficacy of couple-focused interventions. For example, helping couples be more mindful of how the relationship is affected by cancer and assisting them in negotiating the process of incorporating cancer into their relationship may enhance relationship communication and intimacy and ultimately improve the efficacy of couple-focused work. If our work supports the role of relationship awareness in predicting relational intimacy by enhancing relationship communication, these findings will provide evidence to support relationship awareness theory. Our work will also extend the IPM to include the construct of relationship awareness as a precursor to the intimacy processes included in the IPM (e.g., disclosure and responsiveness).

Study Aims

The main aim of the present study was to examine the association between cancer-specific relationship awareness and one’s own communication about cancer, perceptions of one’s partner’s communication about cancer, and relationship intimacy. We focused on cancer-specific relationship talk, self-disclosure, perceived partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness as the communication behaviors potentially associated with greater relationship awareness. There were two hypotheses. First, we proposed that a person’s relationship awareness (whether patient or partner) would be positively associated with his or her own cancer-specific relationship talk, self-disclosure, and how responsive he or she perceives his or her partner to be, which would subsequently be associated with higher levels of relationship intimacy for that person. Greater awareness would be associated with more talk, more disclosure, and more responsiveness, and ultimately, more intimacy. Second, we hypothesized that one’s own awareness and communication would be associated with one’s partner’s intimacy. We hypothesized that the person’s partner’s relationship awareness would be positively associated with the person’s communication (higher levels of relationship talk, self-disclosure, and perceived responsiveness), and that the person’s partner’s communication would be associated with the person’s intimacy.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 254 women with early stage breast cancer and their significant others drawn from a larger randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of a couple-focused group intervention for couples coping with breast cancer (Manne et al., unpublished data). For clarity of presentation, we use the term spouse to denote the patient’s partner, even though there are some partners in the study who were not married to the patient.

Procedure

Patients were approached for study participation from the outpatient clinics of oncologists practicing in three comprehensive cancer centers in the Northeastern United States or in several smaller local community hospital oncology practices. Participants were part of a longitudinal study of the efficacy of two eight session couple-focused group interventions. Criteria for study inclusion were as follows: a) patient had a primary diagnosis of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ or Stage 1, 2, or 3a breast cancer; b) patient had breast cancer surgery; c) patient and spouse were 18 years of age or older; d) patient and spouse were able to give informed consent; e) patient and spouse were English-speaking, and; f) patient currently married or living with a significant other of either sex.

Eligible patients were identified and approached either after an outpatient visit or by telephone contact or by mail. Patient and spouse were given a written informed consent and the study questionnaire to complete and return by mail. Two hundred fifty four couples signed consent forms and completed the baseline survey (14.1%). The most common reason provided for study refusal was that it would take too much time. The majority (62%) did not provide a reason.

Comparisons were made between patient participants and refusers with regard to available data (age, race/ethnicity, cancer stage, performance status). Results indicated that patient participants were significantly younger than non-participants (Mparticipants = 54.8, SD = 10.2, Mrefusers = 56.5, SD = 11.8, t (1780) = 2.2, p < .05). We were not able to compare spouse refusers with participants because we did not have data available on spouse refusers.

Measures Administered

Cancer-specific relationship awareness

This 7-item measure was composed specifically for this study to assess relationship awareness as it applies to cancer. Items were based partially upon forms and examples of relationship awareness provided by Acitelli and Badr (2005), Badr and Acitelli (2005) and Badr, Acitelli, & Taylor (2008). Items assessed the degree to which the participant thought it was important to: maintain normalcy in the relationship during the cancer experience, cope together as a team with changes due to cancer, share good memories and experiences during the cancer experience, share hopes and dreams for the future during the cancer experience, tell their partner what they need in terms of emotional support during the cancer experience, tell their partner what they need in terms of practical support during the cancer experience, and talk to their partner about how cancer may change their future plans. Two sample items from this scale are: “I think it is important that my partner and I maintain as much normalcy as possible in our relationship during the cancer experience,” and “I think it is important that I talk with my partner about our hopes and dreams for the future during the cancer experience.” Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Participants were instructed to rate how they thought about each topic in the past month, and scale scores were computed by summing across the items. Internal consistency as estimated by coefficient alpha is .82 for patients and .80 for spouses.

Cancer-specific Relationship Communication

Cancer-specific relationship talk

This 7-item measure was composed specifically for this study. Items corresponded to topics included in the relationship awareness measure described above, and assessed the degree to which participants talked about the following topics with their spouse during the cancer experience: ways of maintaining closeness during the cancer experience, how the cancer has affected the relationship, future plans they may consider changing as a result of cancer, ways of maintaining normalcy during the cancer experience, good memories and experiences the couple has had together, talked about what they need in terms of emotional support during the cancer experience, talked about what they need in terms of practical support during the cancer experience, expressed their commitment to the relationship through the cancer experience, and hopes and dreams for the future. A sample item from this scale is: “I have talked to my partner about how cancer has affected our relationship.” Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1= strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Participants were instructed to rate what they talked about with their spouse in the past month, and scale scores were computed by summing across the items. The coefficient alpha for patients was .90 and coefficient alpha for spouses was .89.

Cancer-specific self-disclosure

This 3-item measure was adapted from Laurenceau, Barrett, & Pietromonaco (1998) and our previous work (Manne et al., 2004). Participants rated the degree to which they disclosed thoughts, information, and feelings about cancer to their partner in the past week with higher scores indicating greater self-disclosure. Scale scores were computed by summing across the items, and the coefficient alpha for patients was .93 and coefficient alpha for spouses was .91.

Cancer-specific perceived partner disclosure

This 3-item measure was adapted from Laurenceau and colleagues (1998) and our previous work (Manne et al., 2004). Participants rated the degree to which their partner disclosed thoughts, information, and feelings about cancer in the past week with higher scores indicating greater perceived disclosure. Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7= very much), and items were summed to create a scale score. The coefficient alpha for patients was .93 and coefficient alpha for spouses was .93.

Cancer–specific perceived partner responsiveness

This 3-item measure was adapted from Laurenceau et al. (1998) and our previous work (Manne et al., 2004). Participants rated the degree to which they felt accepted, understood, and cared for (“To what degree did you feel cared for by your partner”?) when discussing cancer-related concerns. Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much), and items were summed to create a scale score. The coefficient alpha for patients was .87 and coefficient alpha for spouses was .91.

Global Relationship Intimacy

The Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships (PAIR; Schaefer & Olson, 1981) is a 6-item scale assessing emotional closeness. It has been used in studies of relationship intimacy among healthy married couples (Talmadge, 1990). The coefficient alpha for patients was .87 and the coefficient alpha for spouses was .88. An item mean is used in analyses and higher scores indicate greater intimacy.

Demographic and Medical Information

Age, sex, education, employment status and marital status were collected. Data regarding the patient’s disease stage (1 to 3a), treatment status (chemotherapy, radiation), time since diagnosis, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group symptom ratings were obtained from the medical chart.

Analysis Plan

Our data analytic approach was based on the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) which states that when two individuals are interdependent, one person’s outcomes may be a function of both his/her own inputs and his/her partner’s inputs. We used multilevel modeling (MLM) to assess the basic requirements for a mediational analysis (i.e., that the initial variable predicts the outcome as well as the mediators; Baron & Kenny, 1986). MLM controls for the nonindependence in the partners’ outcome scores while estimating the degree to which a person’s intimacy and relationship communication can be predicted by that person’s own relationship awareness (i.e., an actor effect) as well as his or her partner’s relationship awareness (i.e., a partner effect). In these initial analyses, we first specified models that allowed the size of the actor and partner effects to differ across patients and spouses. However, patient/spouse status did not significantly moderate the size of the actor or partner effects (i.e., none of the actor by role or partner by role interactions were statistically significant), and so these interactions were omitted from these models.

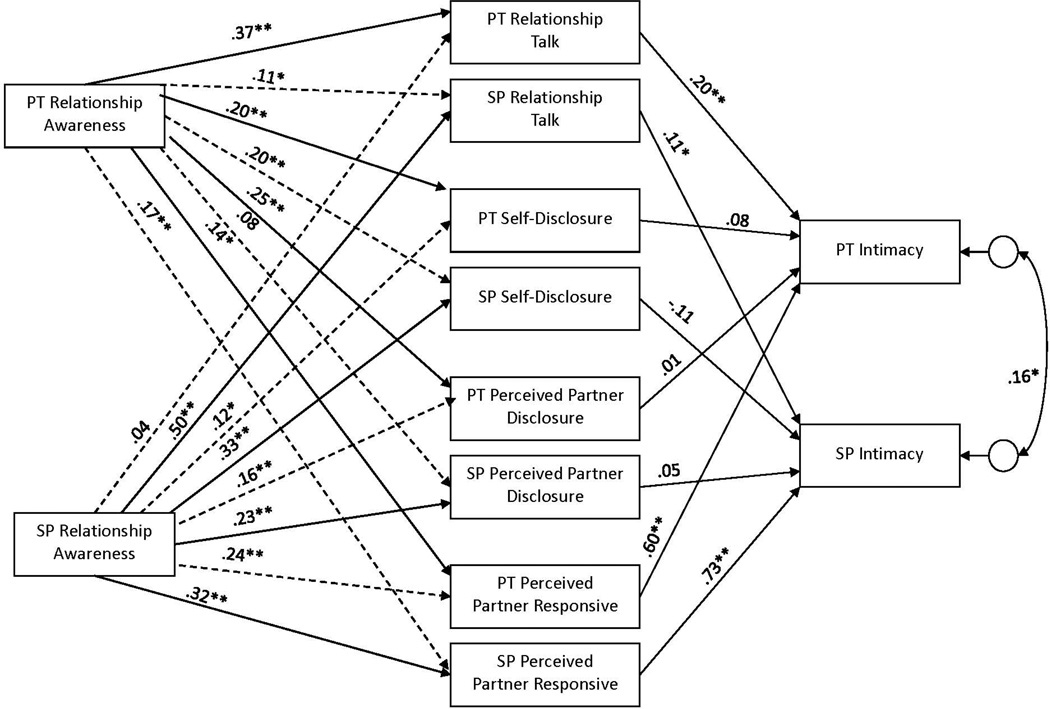

The parameters for the full mediational model depicted in Figure 1 were estimated using structural equation modeling (SEM) with a bootstrapping approach, which again controls for non-independence of the two partners’ outcomes. We used nested models in SEM to test for full mediation, and we used bootstrapping to test the indirect effects.

Figure 1.

Mediation model depicting that the actor and partner effects of relationship awareness on intimacy are mediated by actor effects in relationship communication. PT denotes patient-reported variables and SP denotes spouse/partner-reported variables.

Note. Although not shown, the residuals across all of eight mediator variables were allowed to correlate with one another, as were patient and spouse relationship awareness. Solid lines represent actor effects and dashed lines represent partner effects. Parameters shown are standardized path coefficients

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive information regarding the study sample is shown in Table 1. On average, patients were 56 years of age (SD = 10.2 range = 32 to 83.5), and spouses were 56 years of age (SD = 10.9, range = 29–84). More than half of the sample of patients (56.5%) and spouses (61%) had completed college, and 53% of patients and 67% of spouses were employed either full- or part-time. The majority of patients and spouses were Caucasian. Two hundred forty one couples (95%) were married and the remaining couples were cohabitating (5%). The average relationship length for married couples was 25 years (Patients, SD = 14.1; range= 1 – 62 years; Spouses, SD = 14.3, range = 1–62 years), and the average relationship length for cohabiting couples was about 8 years (Patients, M = 8.2, SD = 6.2, range = 1 to 20 years, Spouses, M = 7.2, SD = 6.5, range = 0–21 years). The majority of the spouses were male (99%) with a very small subset of female spouses (1%). With regard to disease stage, 25.3 % of women were diagnosed with DCIS, 40% with stage 1, 22.9% with stage 2A, 7.9% with stage 2B, and 4.0% with stage 3A breast cancer. The majority of patients (79%) had been diagnosed with cancer within the past six months (M = 4.5 months). At the time of survey completion, patients were undergoing the following treatments after surgery: chemotherapy (n= 66), radiation (n= 45), both chemotherapy and radiation (n = 4), or no treatment (n = 109).

Table 1.

Demographic and Disease Information for Participants

| Variable | Patients | Partners |

|---|---|---|

| N | 254 | 254 |

| Age | 54.8 (10.2) | 56.2 (10.9) |

| Race | ||

| White | 220 (86.6) | 216 (85.0) |

| Non-White | 34 (13.4) | 38 (15.0) |

| Years of education | ||

| < college | 161 (63.3) | 97 (38.2) |

| ≥ college | 93 (36.6) | 151 (59.5) |

| Missing | 2 (.01) | 6 (2.3) |

| Median family income | $98,000 | $96,000 |

| Employment status | ||

| Full time | 101 (39.7) | 152 (59.8) |

| Part time | 34 (13.3) | 13 (5.1) |

| Not employed | 116 (45.7) | 79 (32.3) |

| Missing | 2 (.01) | 10 (3.9) |

| Relationship length | ||

| Married | 25.5 (14.1) | 25.2 (14.3) |

| Unmarried | 8.2 (6.2) | 7.3 (6.5) |

| Stage of disease | ||

| 0 | 57 (22.4) | |

| 1 | 92 (36.2) | |

| 2 | 73 (28.7) | |

| 3a | 9 (3.5) | |

| Type of surgery | ||

| Mastectomy | 71 (28.0) | |

| Breast-conserving | 183 (72.0) | |

| Surgery | ||

| Time Since Diagnosis (months) | 4.5 (2.3) | |

| Current Treatment | ||

| Chemotherapy | 66 (25.9) | |

| Radation | 45 (17.7) | |

| Radiation and Chemotherapy | 4 (1.5) | |

| No treatment | 109 (42.9) | |

| Missing information | 30 (11.8) |

Note. Numbers indicate number and percentage for categorical variables and mean and standard deviations for continuous variables (age, relationship length).

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations for the primary study measures. It is interesting to note that levels of cancer –specific relationship awareness were relatively high, particularly for patients (M = 30.87) with average scores near the top of the range for this scale (highest possible score = 35). However, levels of cancer-specific relationship talk (MPatient = 17.11, MSpouse= 15.85) were lower (the highest possible score = 35). Levels of patient self-disclosure (current study, M = 14.15, previous work, M = 18.5), spouse self-disclosure (current study, M = 13.17, previous work, M = 13.2) and patient perceived partner responsiveness (current study, M = 11.14, previous work, M = 14.1) were lower than averages reported in previous work (Manne et al., 2004). The mean for the intimacy scale (MPatient = 3.96, MSpouse = 4.0) indicated a high level of intimacy (maximum score on this scale = 5).

Table 2.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for Patients and Spouses

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PT Rel Awareness | .37** | .20** | .26** | .15* | .19** | .05 | .14* | .22** | .09 | .18** | .13* | ||

| 2. PT Rel Talk | .42** | .40** | .20** | .35** | .06 | .27** | .14* | .13* | .10 | .09 | |||

| 3. PT Self-Disclosure | .75** | .35** | .37** | .13* | .20** | .29** | .26** | .26** | .16* | ||||

| 4. PT Per Part Disclosure | .43** | .40** | .17** | .19** | .37** | .15* | .29** | .19** | |||||

| 5. PT Per Part Responsive | .68** | .25** | .18** | .20** | .06 | .45** | .45** | ||||||

| 6. PT Intimacy | .15* | .15* | .18** | .08 | .37** | .42** | |||||||

| 7. SP Rel Awareness | .51** | .34** | .23** | .32** | .30** | ||||||||

| 8. SP Rel Talk | .33** | .23** | .25** | .26** | |||||||||

| 9. SP Self-Disclosure | .64** | .42** | .26** | ||||||||||

| 10. SP Per Part Disclosure | .26** | .19** | |||||||||||

| 11. SP Per Part Responsive | .73** | ||||||||||||

| 12. SP Intimacy | |||||||||||||

| Mean | 30.87 | 17.11 | 14.16 | 11.14 | 18.65 | 3.96 | 27.98 | 15.85 | 13.17 | 16.22 | 17.71 | 4.00 | |

| SD | 3.39 | 5.71 | 5.63 | 6.09 | 3.39 | .83 | 4.09 | 5.00 | 4.95 | 4.68 | 3.85 | .82 | |

Note. PT = patient; SP = spouse; per = perceived; part = partner, rel= relationship

Related groups t-tests were used to test for differences between patients and spouses on the six measures. Patients reported significantly higher cancer–specific relationship awareness, t(253) = 8.87, p < .01, higher levels of cancer–specific relationship talk, t(253) = 3.10, p < .01 and self-disclosure, t(253) = 2.36, p = .02. Spouses reported higher levels of perceived partner disclosure, t(253) = 11.38, p < .01 and patients reported higher levels of perceived partner responsiveness t(253) = 3.93, p < .01. Finally, patients and spouses did not differ significantly in their reports of intimacy, t(253) = .75, p = .45.

Main Analysis Results

Table 3 presents the standardized and unstandardized regression coefficients derived from the initial APIM analyses. Each row of the table represents a separate MLM analysis in which a person’s standing on a variable (e.g., intimacy) is predicted to be a function of that person’s own relationship awareness as well as the person’s partner’s relationship awareness. The significant actor and partner coefficients depicted in the top row of Table 3 indicate that a person’s intimacy can be predicted by both the person’s own cancer-specific relationship awareness as well as his or her partner’s relationship awareness. Note that because the APIM analyses simultaneously include actor and partner relationship awareness as predictors, these coefficients estimate partial relationships for the effects of each person’s awareness over and above the effects of their partner’s awareness. Given that both coefficients are positive, these results suggest that individuals who show greater cancer-specific awareness reported more relationship intimacy and that individuals whose partners show greater cancer-specific relationship awareness also reported more relationship intimacy.

Table 3.

Actor-Partner Interdependence Model Regression Coefficients Predicting each Relationship Variable Separately as a Function of Relationship Awareness

| Predictor Variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actor’s Relationship Awareness |

Partner’ Relationship Awareness |

|||||

| Outcome Variable | b | χ2 | Se | b | χ2 | se |

| Global Intimacy | 0.05** | .26 | 0.01 | 0.03** | .14 | 0.01 |

| Cancer-specific Relationship Talk | 0.61** | .45 | 0.06 | 0.11* | .09 | 0.06 |

| Cancer –specific Self-Disclosure | 0.41** | .30 | 0.06 | 0.21** | .16 | 0.06 |

| Cancer –specific Perceived Partner Disclosure | 0.31** | .21 | 0.06 | 0.18** | .12 | 0.06 |

| Cancer-specific Perceived Partner Responsiveness | 0.22** | .24 | 0.04 | 0.19** | .21 | 0.04 |

Note

p < .05

p < .01

The remaining APIM results from Table 3 support the proposition that the four relationship communication variables are potential mediators of the link between cancer-specific relationship awareness and intimacy. These results suggest that individuals who were themselves higher in relationship awareness talked about their relationship more, reported higher levels of self-disclosure, perceived that their partners also disclosed more, and perceived that their partners were more responsive. The partner effects for relationship awareness are particularly compelling because a) they represent the degree to which the partner’s relationship awareness predicts their own outcomes while controlling for their own awareness, and b) they do not share method variance with the outcomes. The partner effects for relationship awareness suggest that individuals whose partners report higher awareness talk about their relationship more and self-disclose to a greater extent. Moreover, individuals with more aware partners perceive that those partners disclose more and are more responsive.

The primary mediational analysis was conducted using SEM with the bootstrapping procedure recommended by MacKinnon (2008). In this model, presented in Figure 1, we specified that the effects of the two partners’ cancer-specific relationship awareness on their reports of intimacy were mediated by the four communication variables. Given the consistent partner effects of awareness on the communication variables, our model included both actor and partner effects from relationship awareness to the mediators. However, because there was no evidence of partner effects for any of the communication variables on intimacy, we included only actor effects for communication on intimacy. For example, our model in Figure 2 states that both the patients’ and their spouses’ relationship awareness predicts the patients’ relationship talk and the patients’ relationship talk in turn predicts the patients’ intimacy. Likewise, the patients’ and partner’s awareness predicts the spouses’ relationship talk and the spouses’ talk predicts the spouses’ intimacy.

Model fit for the fully mediated model as presented in the figure was quite good across several measures of model fit, with χ2(12) = 19.06, p = .087, CFI = .994, RMSEA = .048, pclose = .482. We also estimated a model that specified only partial mediation. This model included all paths in the figure as well as direct paths from patients’ and spouses’ awareness to the patients’ and spouses’ intimacy. Note that these paths included both actor and partner paths for awareness to intimacy, and so this model differs from the fully mediated model by the addition of four parameters. The fit for the model that included direct paths to intimacy was χ2 (8) = 17.22, p = .028, CFI = .992, RMSEA = .067, pclose = .221. Therefore, the chi-square difference test, χ2(4) = 1.84, n.s., suggests that the actor and partner effects for relationship awareness on intimacy are fully mediated by the four mediators specified in the model. Consistent with this, the direct actor and partner effects for relationship awareness on intimacy, controlling for the effects of the mediators, were all small and did not approach statistical significance (i.e., all p’s > .24).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to evaluate the role of cancer-specific relationship awareness in the communication and relationship intimacy of women diagnosed with breast cancer and their partners. Guided by the relationship awareness and IPM theories, we proposed that cancer-specific relationship awareness would predict higher levels of relationship talk, self-disclosure, and responsiveness to one’s partner as well as perceptions of one’s partner’s disclosure and responsiveness. We proposed that these communication behaviors would, in turn, be associated with greater relationship intimacy. Because we were using actor-partner interdependence analyses, we were able to evaluate whether one person’s awareness was associated with one’s own communication and intimacy as well as the other person’s communication, the other person’s perceptions of the person’s communication, and the other person’s intimacy. Our results were largely consistent with our hypotheses. We found that patients who were higher in relationship awareness engaged in more relationship talk, reported higher levels of self-disclosure, and perceived that their spouse disclosed more. Their spouses perceived that they were more responsive to their disclosures, as well. The same findings were present among spouses. Moreover, patients reporting higher relationship awareness had spouses who engaged in more relationship talk and who reported disclosing more to them. Spouses reporting higher relationship awareness had patient partners who disclosed more. When we evaluated the hypothesized meditational role for communication, our results were partially consistent with hypotheses. The association between both partner’s relationship awareness and the person’s intimacy was fully mediated by the person’s relationship talk and perceived partner responsiveness. In contrast to our hypotheses, the association between relationship awareness and intimacy was not mediated by self- or perceived partner-disclosure. The anticipated contributions of these findings to both the literature on marital intimacy and communication in the context of cancer as well as the existing literature on interpersonal processes and intimacy will be reviewed.

Attitudes about the way a stressful experience such as cancer is incorporated into one’s relationship play an important role in how well couples maintain relational quality when a stressor occurs. However, how a specific stressor such as cancer is incorporated into a relationship has received little empirical attention, and the link between relationship attitudes (e.g., awareness) and indicators of relationship quality (e.g., intimacy) is poorly understood. Acitelli (2002) has suggested that awareness is manifested in talking about the relationship which leads to relationship outcomes such as how satisfied the person is with the relationship. Our findings support this contention. Couples who explicitly talk about how they can maintain normalcy, closeness, and hope for the future with one another in the face of cancer do report greater intimacy, which is consistent with Acitelli’s conceptualization of relationship awareness (2002). Second, they may disclose more about their cancer worries and be more responsive to their partner’s disclosures about cancer concerns.

Although a dyadic focus is implicit in all relationship theories, APIM analyses allow researchers to study the impact of partners on one another. Our study extends prior work by suggesting that the relationship awareness of one partner is associated with the communication on the part of the other partner. That is, greater relationship awareness of one partner may have facilitated relationship talk on the part of the other partner, indicating that one partner’s relationship perspective may be perceived by the other partner.

It is interesting to note that, although cancer-specific relationship awareness was associated with all four relationship communication variables studied, only relationship talk and perceived partner responsiveness mediated the association between relationship awareness and intimacy. Neither self-disclosure nor perceived partner disclosure mediated the association. These findings are actually consistent with the IPM in that it hypothesizes that the association between disclosure and intimacy is mediated by perceived partner responsiveness (that is, there is no direct association). Because this paper focuses on the relationship awareness component of the model, we did not present results evaluating this mediational step. Nonetheless, we conducted a series of follow-up analyses using the APIM to evaluate whether the link between intimacy and actor and partner disclosure was mediated by perceived responsiveness, and there was evidence of partial mediation.

Theoretical Implications

Our work has implications both for the study of intimacy during the diagnosis and treatment for breast cancer, as well as implications for research on relationship intimacy processes. Research on relationship processes for couples coping with cancer should assess how well couples incorporate cancer into the way they think about their relationship, because the degree that this is accomplished facilitates the maintenance of closeness from both partners’ perspectives and may underlies couples’ communication behaviors. In terms of general relationship intimacy processes (not cancer), linking relationship attitudes and cognitions such as relationship awareness to couples’ behaviors can help inform theories of how intimacy is maintained and expand intimacy theories such as the IPM to include attitudes and cognitions that drive discussion about difficult topics and responsiveness to one’s partner. In the same way that attributional patterns regarding blame and responsibility for partner behavior may underlie marital distress (Bradbury & Fincham, 1990) and may predict critical communication towards one’s partner (Peterson & Smith, 2011), our research suggests that identifying underlying attitudes about how a life stressor can be incorporated into the relationship may enrich our understanding of how intimacy is maintained in close relationships during stressful life experiences. Future research evaluating interpersonal processes of intimacy may benefit from including global relationship attitudes about how relationship quality is maintained. Although we utilized two relationship theories in the present work, future research may also benefit from incorporating theoretical constructs and measures from the communal coping framework (Lyons, Mickelson, Sullivan, & Coyne, 1998). The communal coping framework is defined as a cooperative problem solving process which involves the appraisal of stressors as “our” issue. That is, partners hold the belief that joining together to deal with a problem is beneficial. Couples adopting a communal coping orientation utilize both communication strategies and problem solving strategies that are relationship-focused. That is, the choice of coping strategies take into account both partners and the relationship. For example, empathy-driven coping strategies may involve communication strategies such as protective buffering. Buffering may be used to minimize the harm to one’s partner by not broaching upsetting topics to one’s partner (Coyne & Fiske, 1992).

Although our model suggests that talking about cancer and the relationship enhances intimacy, we did not assess the quality of and/or topics of the couples’ discussions about cancer. It is also possible that sharing cancer concerns is not always beneficial. Indeed, there is a literature that suggests that avoiding talking about certain issues may not be detrimental to relationship satisfaction, particularly when the breast cancer patient feels it is safe to talk but she does not wish to do so (Donovan-Kicken & Caughlin, 2010). That is, the goals of specific communications must be taken into account when evaluating their impact on relationship intimacy. Communications have multiple goals, with some communications serving to enhance intimacy and some communications serving other functions which may protect the relationship from harm (Clark & Delia, 1979). Managing these competing goals within a relationship may lead to censorship of some topics of discussion (Sillars, 1998). Thus, in future research it may be important to consider the goal of specific disclosures and to assess possible avoidance of discussing certain topics when evaluating whether relationship communication benefits relationship intimacy.

Clinical Implications

Our work suggests that couple-focused interventions may benefit from focusing on attitudes, not just behaviors. Traditional approaches to couple-based interventions delivered to cancer patients focus on enhancing communication and support behaviors (Baucom et al., 2009; Manne, Ostroff, Winkel, Fox et al., 2005; Porter et al., 2009; Scott, Halford, & Ward, 2004). Our work suggests that focusing on underlying relationship attitudes and schemas, and specifically, coaching couples to consider cancer in relational terms (e.g., “our illness” rather than “my/her illness”), helping couples to think about ways they can maintain normalcy and quality during the cancer experience, helping couples reflect upon changes to their identity and priorities as individuals and as a couple that have been caused by the cancer, and framing coping with cancer as a “team” effort may facilitate better communication and ultimately enhance relationship intimacy. This broader approach to intervention translates to reflective exercises where the couple talks about how the cancer has impacted their relationship, how they can solve issues as a team, and how they can use relationship maintenance strategies to balance the demands of cancer with their normal, pre-cancer routines.

Study Limitations

This study had limitations. First, study acceptance was relatively low, probably due to the fact that the data were taken from the baseline survey from a couple-focused group intervention trial. Second, participants were primarily Caucasian and relatively young. A more diverse sample in terms of race/ethnicity might have revealed different findings. A relatively young sample may have biased the results towards more distressed individuals and/or couples. Third, we used self-report measures of spousal communication and these may not reflect actual behaviors. Although the actor-partner interdependence model addresses some of this concern, it still may have been helpful to assess behaviors. Fourth, and most importantly, this was a cross-sectional study. We cannot form causal conclusions from these data. Although our model hypothesizes a perspective on how intimacy is enhanced, it is possible that patients and partners who feel closer to their partners made more effort to be aware of the impact of cancer on their relationship and try to maintain relationship quality in the face of this stressor. Although we hypothesized that relationship awareness promotes talking to one’s partner about the cancer, we cannot be certain that this is the causal sequence. It is also possible that talking with one’s partner about cancer promotes relationship awareness. Longitudinal data could address this possibility.

Conclusions

The current study indicates that it is important to consider relationship awareness when trying to understand relationship intimacy among couples coping with early stage breast cancer. Underlying attitudes about how difficult life experiences such as cancer are incorporated into an existing close relationship may guide how much and how well couples communicate about the illness as well as ultimately how close they feel to one another during this experience.

Contributor Information

Sharon L. Manne, The Cancer Institute of New Jersey, 195 Little Albany St., New Brunswick, NJ, 08903.

Scott Siegel, Helen F. Graham Cancer Center, Newark, DE.

Deborah Kashy, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

Carolyn J. Heckman, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, PA.

References

- 1.Acitelli L. When spouses talk to one another about their relationship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1988;5(2):185–199. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acitelli L. Gender differences in relationship awareness and marital satisfaction among young married couples. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18(1):102–110. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acitelli L. You, me and us: perspectives on relationship awareness. In: Duck SW, editor. Understanding relationship processes 1: Individuals and relationships. London: Sage; 1993. pp. 144–174. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acitelli L. Relationship awareness: Crossing the bridge between cognition and communication. Communication Theory. 2002;12(1):92–112. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acitelli L, Badr H. My illness or our illness? Attending to the relationship when one partner is ill. In: Revenson T, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Emerging perspectives on couples coping with stress. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acitelli L, Duck S. Intimacy as the proverbial elephant. In: Perlman D, Duck SW, editors. Intimate relationships: Development, dynamics, and deterioration. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1987. pp. 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acitelli L, Rogers S, Knee C. The role of identity in the link between relationship thinking and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1999;16(5):591–619. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badr H, Acitelli LK. Dyadic adjustment in chronic illness: does relationship talk matter? Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(3):465–469. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badr H, Acitelli L, Duck S, Carl W. Weaving social support and relationships together. In: Duck S, editor. Personal relationships: Their implications for clinical and community psychology. Chichester, England: Wiley; 2001. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badr H, Taylor CL. Effects of relationship maintenance on psychological distress and dyadic adjustment among couples coping with lung cancer. Health Psychology. 2008;27(5):616–627. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, Gremore TM, Wiesenthal N, Aldridge W, et al. A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(3):276–283. doi: 10.1002/pon.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernal G, Baker J. Toward a metacommunicational framework of couple interactions. Family Process. 1979;18(3):293–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1979.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradbury TN, Fincham FD. Attributions in marriage: review and critique. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(1):3–33. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canary D, Stafford L. Maintaining relationships through strategic and routine interaction. In: Canary DJ, Stafford L, editors. Communication and Relationship Maintenance. San Diego: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canary D, Stafford L, Semic B. A panel study of the associations between maintenance strategies and relational characteristics. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(2):395–406. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cate RM, Koval J, Lloyd SA, Wilson G. Assessment of relationship thinking in dating relationships. Personal Relationships. 1995;2(2):77–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark RA, Delia JG. TOPOI and rhetorical competence. Quarterly Journal of Speech. 1979;65(2):187–206. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coyne J, Fiske V. Couples coping with chronic illness. In: Akamatse TJ, Crowther JC, Hoboll SC, Stevens M, editors. Family Health Psychology. Washington, DC: Hemisphere; 1992. pp. 129–149. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dindia K, Baxter LA. Strategies for Maintaining and Repairing Marital Relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1987;4(2):143–158. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ditzen B, Schmidt S, Strauss B, Nater UM, Ehlert U, Heinrichs M. Adult attachment and social support interact to reduce psychological but not cortisol responses to stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2008;64(5):479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donovan-Kicken E, Caughlin JP. A multiple goals perspective on topic avoidance and relationship satisfaction in the context of breast cancer. Communication Monographs. 2010;77(2):231–256. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez-Ortega P, Caloto MT, Chirveches E, Marquilles R, Francisco JS, Quesada A, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in clinical practice: impact on patients' quality of life. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20(12):3141–3148. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1448-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fletcher GJ, Fincham FD, Cramer L, Heron N. The role of attributions in the development of dating relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53(3):481–489. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fletcher KA, Lewis FM, Haberman MR. Cancer-related concerns of spouses of women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19(10):1094–1101. doi: 10.1002/pon.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foran HM, Slep AM. Validation of a self-report measure of unrealistic relationship expectations. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(4):382–396. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallagher J, Parle M, Cairns D. Appraisal and psychological distress six months after diagnosis of breast cancer. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2002;7(Part 3):365–376. doi: 10.1348/135910702760213733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giese-Davis J, Hermanson K, Koopman C, Weibel D, Spiegel D. Quality of couples’ relationship and adjustment to metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14(2):251–266. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldsmith DJ, Baxter LA. Constituting relationships in talk: A taxonomy of speech events in social and personal relationships. Human Communication Research. 1996;23(1):87–114. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gotay CC. The experience of cancer during early and advanced stages: the views of patients and their mates. Social Science and Medicine. 1984;18(7):605–613. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greeff AP, Malherbe HL. Intimacy and marital satisfaction in spouses. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2001;27(3):247–257. doi: 10.1080/009262301750257100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guerrero LK, Eloy SV, Wabnik AI. Linking maintenance strategies to relationship development and disengagement: A reconceptualization. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1993;10(2):273–283. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jenewein J, Zwahlen RA, Zwahlen D, Drabe N, Moergeli H, Buchi S. Quality of life and dyadic adjustment in oral cancer patients and their female partners. European Journal of Cancer. 2008;17(2):127–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kenny D, Kashy D, Cook W. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim Y, Kashy DA, Spillers RL, Evans TV. Needs assessment of family caregivers of cancer survivors: three cohorts comparison. Psychooncology. 2010;19(6):573–582. doi: 10.1002/pon.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lang A, Gottlieb LN, Amsel R. Predictors of husbands' and wives' grief reactions following infant death: the role of marital intimacy. Death Studies. 1996;20(1):33–57. doi: 10.1080/07481189608253410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laurenceau JP, Barrett LF, Pietromonaco PR. Intimacy as an interpersonal process: the importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74(5):1238–1251. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyons S, Mickelson K, Sullivan M, Coyne J. Coping as a Communal Process. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998;15(5):579–605. [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacKinnon D. Introduction to statistical mediation analyses. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manne S, Ostroff J, Rini C, Fox K, Goldstein L, Grana G. The interpersonal process model of intimacy: the role of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and partner responsiveness in interactions between breast cancer patients and their partners. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(4):589–599. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manne S, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples' psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2541–2555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manne SL, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, Fox K, Grana G, Miller E, et al. Couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(4):634–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manne SL, Ostroff J, Winkel G, Grana G, Fox K. Partner unsupportive responses, avoidant coping, and distress among women with early stage breast cancer: patient and partner perspectives. Health Psychology. 2005;24(6):635–641. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McNeely ML, Binkley JM, Pusic AL, Campbell KL, Gabram S, Soballe PW. A prospective model of care for breast cancer rehabilitation: postoperative and postreconstructive issues. Cancer. 2012;118(8 Suppl):2226–2236. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metis S, Cupach WR. The influence of relationship beliefs and problem-solving responses on satisfaction in romantic relationships. Human Communication Research. 1990;17(1):170–185. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minton O, Stone P, Richardson A, Sharpe M, Hotopf M. Drug therapy for the management of cancer related fatigue. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(1):CD006704. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006704.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Northouse L, Templin T, Mood D, Oberst M. Couples' adjustment to breast cancer and benign breast disease: a longitudinal analysis. Psychooncology. 1998;7(1):37–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199801/02)7:1<37::AID-PON314>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olson DH. The circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy. 2000;22(2):144–167. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Omne-Ponten M, Holmberg L, Burns T, Adami HO, Bergstrom R. Determinants of the psycho-social outcome after operation for breast cancer. Results of a prospective comparative interview study following mastectomy and breast conservation. European Journal of Cancer. 1992;28A(6–7):1062–1067. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90457-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paskett ED, Dean JA, Oliveri JM, Harrop JP. Cancer-related lymphedema risk factors, diagnosis, treatment, and impact: a review. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(30):3726–3733. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.8574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peterson KM, Smith DA. Attributions for spousal behavior in relation to criticism and perceived criticism. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42(4):655–666. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pistrang N, Barker C. Partners and fellow patients: two sources of emotional support for women with breast cancer. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26(3):439–456. doi: 10.1023/a:1022163205450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Baucom DH, Hurwitz H, Moser B, Patterson E, et al. Partner-assisted emotional disclosure for patients with gastrointestinal cancer: results from a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4326–4338. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prager KJ, Buhrmester D. Intimacy and need fulfillment in couple relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998;15(4):435–469. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reis H, Patrick B. Attachment and intimacy: Component processes. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 523–563. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reis H, Shaver P. Intimacy as an interpersonal process. In: Duck S, editor. Handbook of personal relationships. Chichester, England: Wiley; 1988. pp. 367–389. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schaefer MT, Olson DH. Assessing intimacy: The PAIR Inventory. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1981;7(1):47–60. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scott JL, Halford WK, Ward BG. United we stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on adjustment to early stage breast or gynecological cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(6):1122–1135. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sillars AL. (Mis)understanding. In: Spitzberg BH, Cupach WR, editors. The dark side of close relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 73–102. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Solomon DH, Weber KM, Steuber KR. Turbulence in relational transitions. In: Smith SW, Wilson SR, editors. New directions in interpersonal communication research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010. pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Talmadge LD, Dabbs JM. Intimacy, conversational patterns, and concomitant cognitive/emotional processes in couples. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9(4):473–488. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uebelacker L, Whisman M. Relationship beliefs, attributions, and partner behaviors among depressed married women. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2005;29(2):143–154. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vanzetti N, Notarias C. New York: 24th annual convention of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy; 1991. Relational efficacy: A summary of findings. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Von Ah D, Habermann B, Carpenter JS, Schneider BL. Impact of perceived cognitive impairment in breast cancer survivors. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2013;17(2):236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weber KM, Solomon DH. Locating relationship and communication issues among stressors associated with breast cancer. Health Communication. 2008;23(6):548–559. doi: 10.1080/10410230802465233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yeo W, Kwan WH, Teo PM, Nip S, Wong E, Hin LY, et al. Psychosocial impact of breast cancer surgeries in Chinese patients and their spouses. Psychooncology. 2004;13(2):132–139. doi: 10.1002/pon.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zahlis EH, Lewis FM. Coming to grips with breast cancer: the spouse's experience with his wife's first six months. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2010;28(1):79–97. doi: 10.1080/07347330903438974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zahlis EH, Shands ME. The impact of breast cancer on the partner 18 months after diagnosis. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 1993;9(2):83–87. doi: 10.1016/s0749-2081(05)80103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zerach G, Anat BD, Solomon Z, Heruti R. Posttraumatic symptoms, marital intimacy, dyadic adjustment, and sexual satisfaction among ex-prisoners of war. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7(8):2739–2749. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]