Abstract

Background

microRNA (miRNA) functions broadly as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression, and disproportionate miRNAs can result in dysregulation of oncogenes in cancer cells. We have previously shown that gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRP-R) signaling regulates tumorigenicity of neuroblastoma cells. Here, we sought to characterize miRNA profile in GRP-R silenced neuroblastoma cells, and to determine the role of miRNAs on tumorigenicity and metastatic potential.

Methods

Human neuroblastoma cell lines, BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH, were used for our study. Stably-transfected GRP-R silenced cells were assessed for miRNA profiles. Cells were transfected with miR-335, miR-363, or miR-CON, a non-targeting control, and in vitro assays were performed. In vivo functions of miR-335 and miR-363 were also assessed in spleen-liver metastasis murine model.

Results

GRP-R silencing significantly increased expression of miR-335 and miR-363 in BE(2)-C cells. Overexpression of miR-335 and miR-363 decreased tumorigenicity as measured by clonogenicity, anchorage-independent growth, and metastasis determined by cell invasion assay and liver metastasis in vivo.

Conclusions

We report, for the first time, that GRP-R-mediated tumorigenicity and increased metastatic potential in neuroblastoma are regulated, in part, by miR-335 and miR-363. A better understanding of the anti-tumor functions of miRNAs could provide valuable insights to discerning molecular mechanisms responsible for neuroblastoma metastasis.

Keywords: GRP, microRNA, Neuroblastoma, Metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Neuroblastoma is the most common extracranial tumor in infants and children. The overall outcome ranges from successful cure or spontaneous regression in infants <18 months to high mortality in the majority of metastatic disease in children >18 months.1 Tumor metastasis remains as one of the major causes for high morbidity and mortality in patients with neuroblastoma, where >50% have distant organ disease involvement at diagnosis.2 Thus, it is imperative to elucidate the cellular mechanisms and to identify potential therapeutic targets for metastatic neuroblastoma.

Recently, microRNA (miRNA) has become increasingly relevant in cancer research. miRNAs are small, non-coding RNAs that functionally repress target proteins via RNA-RNA binding at imperfect complementary sequences within the 3′untranslated region (3′UTR) of the target mRNA, causing either mRNA degradation or translational inhibition. It has become abundantly clear that they play fundamental roles in development of cancer. miRNAs can target expression of more than one gene, including oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Thus, miRNAs can regulate many cellular processes such as metastasis, which contributes to the tumorigenicity of cancers.3 In particular, miR-335 has been reported to function as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting tumor reinitiation in breast cancer.4 In neuroblastoma, miR-34a, miR-184 and miR-335 have been described as potent tumor suppressor miRNAs.5–7

Non-metastatic and metastatic neuroblastomas have aberrantly different miRNA profiles.8 Specifically, miR-335 has been shown to act as a suppressor of tumor metastasis by regulating TGF-β non-canonical pathways leading to inactivation of the motor protein myosin light chain which results in decreased migratory and invasive potential of neuroblastoma cells.9 miR-335 has been shown to have similar anti-metastatic properties in breast cancer by targeting sex determining region Y-box 4 (SOX4) and tenascin C (TNC).10 In addition, miR-363 has been associated with gastric cancer. It may potentially target disintegrin and metalloproteinase 15 (ADAM15) in aggressive gastric cancer,11 which affects cell adhesion and migration.12 miR-363 has also been shown to regulate myosin-1b (MYO1B) which regulates cell motility and migration in HPV-positive squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck.13

We have previously shown that gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRP-R)-mediated signaling is critical to the tumorigenicity and metastatic potential of neuroblastoma cells.14–16 In this study, we found that expressions of miR-335 and miR-363 are decreased in neuroblastoma cells. Conversely, GRP-R silenced neuroblastoma cells which feature less invasive cell property, showed upregulation of miR-335 and miR-363. We report that the decreased tumorigenicity and metastatic potential of GRP-R silenced neuroblastoma is partly regulated by miR-335 and miR-363, involving downstream targets such as SOX4, TNC, ADAM15 and MYO1B.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

miRNA array RT2 miRNA PCR Array Human Cancer (MAH-102A) was from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Lenti-miRNA expression systems were purchased from Applied Biological Materials Inc. (Richmond, BC Canada). Luciferase expression vector pMSCV-LucSh, which contains fused luciferase and zeocin-resistance gene was kindly provided by Dr. Andrew M. Davidoff (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) was from Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD). Agarose (SeaPlaque®) was from Cambrex Bio Science (East Rutherford, NJ). D-luciferin was from Gold Biotechnology Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Other chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Cell cultures and transfection

Human neuroblastoma cell lines, BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH, were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media with L-glutamine (Cellgro Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Luciferase-expressing cells were obtained by selection with zeocin at 50 μg/ml. Stable populations of miRNA expressing cells were obtained by lentiviral infection with luciferase-expressing cells and selected with zerocin at 50 μg/ml and puromycin at 2.5 μg/ml. miRNA mimics and their controls of miR-335 and miR-363 were purchased from SwitchGear Genomics Store (Menlo Park, CA) and used for transient transfection to exclude nonspecific effects.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well) in RPMI 1640 media with 10% FBS and grown for up to 96 h post-transfection. Cell number was assessed daily using CCK-8. Each time point assay was performed in triplicate. The values corresponding to the number of viable cells were read at OD450 with FlexStation 3 Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices. Sunnyvale, CA).

Anchorage-independent colony growth

Anchorage-independent growth was measured by assessing for colony formation in a soft agar suspension. Cells were trypsinized and resuspended in RPMI 1640 media containing 0.4% agarose and 7.5% FBS. Cells were overlaid onto a bottom layer of solidified 0.8% agarose in RPMI 1640 media containing 5% FBS, at a concentration of 2 × 103 cells per well in 12-well plates. After solidifying, 500 μl of media was plated on top of the second agar layer to prevent over drying. Assays were incubated for 2 weeks before being stained with 0.005% crystal violet, and then imaged with the Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR+ Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Quantity One Gel Doc version 4.6.9 software from Bio-Rad was used to count the colonies.

Clonogenic assay

Cells were trypsinized and resuspended in RPMI 1640 media with 10% FBS and plated in 6-well plates (1 × 103 cells/well) and incubated for 10 days. Colonies were fixed and stained with 0.005% crystal violet in 70% methanol for overnight. The colony images were taken with Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR+ Imaging System, and quantitated using Bio-Rad Quantity One Gel Doc version 4.6.9 software. All cultures were performed in triplicate and the experiments for each miRNA were repeated three times.

Cell invasion assay

Transwell filters (8 μm; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) were coated with 100 μl Matrigel (BD Biosciences) at 1:30 dilution in media and incubated overnight. Cells (1 × 105) in serum-free media were added to the upper chamber and RPMI media with 10% FBS were added to the bottom wells. After 48 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with DAPI and counted. Assay was performed in duplicates and cells were counted from five randomly selected microscopic fields.

Quantitative real-time PCR (QRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using the RNAqueous™ (Life Technologies). Isolated RNA (1 μg) was used to synthesize cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies). QRT-PCR was performed in the CFX96™ Real-Time PCR Detection Systems using SsoFast™ EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad). Primers were used for QRT-PCR as following: ADAM15 (NM_001261464) forward primer 5′-ATCAAGTTGGAGCTGGACGG-3′, reward primer 5′-CATATCCCCGCACTCTTCCC-3′; MYO1B (NM_001130158) forward primer 5′-ATATCG GGGGTGGAAATGCC-3′, reward primer 5′-TGCTTCAGTTCCCGCAGAAT-3′; SOX4 (NM_003107) forward primer 5′-GACCTGAACCCCAGCTCAAA-3′, reward primer 5′-GAT CATCTCGCTCACCTCGG-3′; TNC (NM_002160) forward primer 5′-GGGCTGGTTGTA TTGATGCTTT-3′, reward primer 5′-AGGGACCACTGGGTGAGAGA-3′; GAPDH (NM_002046) forward prier 5′-TCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCGACACC-3′, reward primer 5′-TCTCTCTTCCTCTTGTGCTCTTGG-3′.

Tumor metastasis in vivo

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with guidelines issued by the NIH. Male athymic nude mice (4–6 weeks old) were maintained as described previously.16 Cells stably transfected with luciferase and miRNAs were injected into the spleen of mice at a concentration of 0.5 × 106 cells/50 μl HBSS per mouse. Metastases were monitored by detecting luciferase signals with bioluminescence imaging system (IVIS Lumina II, Xenogen, and Caliper Life Sciences, Waltham, MA) and body weights were measured weekly. Mice were injected with D-luciferin (Gold Biotechnology, St. Louis, MO) subcutaneously (1 mg/mouse in 100 μl of HBSS) before anesthetized with isofluorane. Measurement of total flux (photons/sec) of the emitted light reflects the relative number of viable cells in the tumor. Data were analyzed using Xenogen Living Image software (version 4.1). At sacrifice, spleens and livers were harvested, weighed and fixed in formalin for analyses.

Statistical analysis

In vitro data represent the means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using a Student’s paired t test. In vivo experiments were analyzed as described.16, 17 p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

miRNA profiling in GRP-R silenced BE(2)-C cells

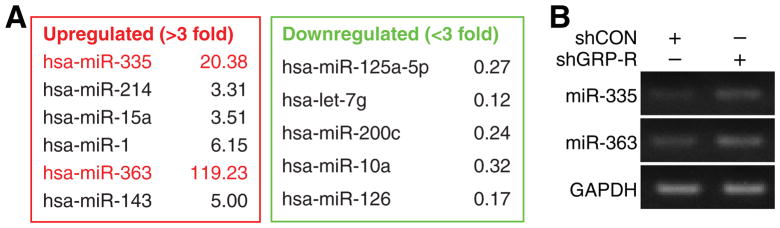

miRNA profiling of metastatic neuroblastoma allows us to discriminate miRNAs that are exclusively associated with secondary site disease spread. We had previously reported that targeted silencing of GRP-R in neuroblastoma results in inhibition of both subcutaneous xenografts as well as liver metastases.16 We performed miRNA arrays with human neuroblastoma BE(2)-C cells that have been stably-transfected to target silence GRP-R (shGRP-R) or control vector (shCON) using RT2 miRNA PCR Array Human Cancer (MAH-102A). We found that 24 out of 84 miRNAs were altered more than two-fold in GRP-R silenced cells, suggesting that these miRNAs may play important roles in both tumorigenesis and metastasis. Among them, six miRNAs showed >3-fold expression increases with GRP-R targeted silencing (Fig. 1A). In particular, expressions of miR-335 and miR-363 were increased by 20- and 119-fold, respectively. We further confirm shGRP-R-induced upregulation of miR-335 and miR-363 using RT-PCR (Fig. 1B). Based on this initial observation, we speculated that these miRNAs could have important functions as tumor suppressors in the regulation of neuroblastoma tumorigenesis and metastasis.

Figure 1. miRNA profile in GRP-R silenced BE(2)-C human neuroblastoma cells.

(A) miRNA array was performed with RT2 miRNA PCR Array Human Cancer (Qiagen) with microRNAs isolated from control (BE(2)-C/shCON) and GRP-R silenced cells (BE(2)-C/shGRP-R). Significant miRNA expression changes by >3-fold are listed. (B) Increased expression of miR-335 and miR-363 by miRNA array was further confirmed by RT-PCR. GAPDH was used as control.

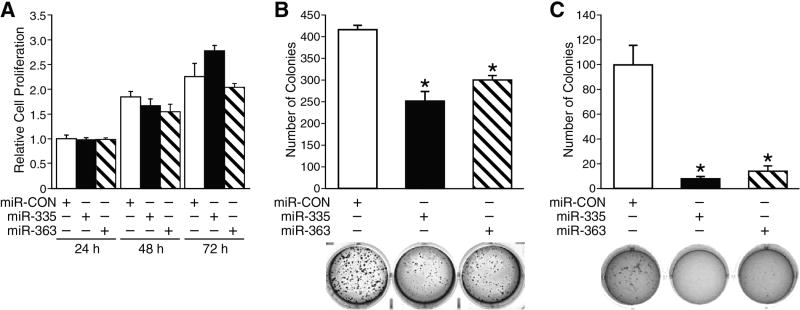

miR-335 and miR-363 inhibited colony formation and anchorage-independent growth

In order to determine the biological functions of miR-335 and miR-363, we stably transfected BE(2)-C cells with vectors expressing miR-335, miR-363 or control (miR-CON).. First, we performed cell growth assay by plating cells in 96-well plates and then cell proliferation effects of miR-335 and miR-363 was measured. We found that overexpression of miR-335 or miR-363 did not significantly affect cell proliferation (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained with transient transfection of BE(2)-C cells with miRNA mimics and inhibitors (data not shown). Since these results may not be representative of the division property of individual cells in whole population, we next performed clonogenic assay, which is an essential assay to determine the ability of each cell to undergo “unlimited” division.18 Cells were plated in 6-well plate and cultured for 10 days. We found that overexpression of either miR-335 or miR-363 significantly reduced the number of colonies to 55% and 68%, respectively, in comparison to control, thus indicating tumor suppressive property of miR-335 and miR-363 (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, we performed soft agar colony formation assay in order to examine the anchorage-independent growth ability, one of the hallmarks of cell transformation. This method has been accepted as in vitro assay for detecting cell malignancy and correlates with tumorigenicity in vivo.19 BE(2)-C cells transfected with miR-335, miR-363, or miR-CON were plated in soft agar and cultured for 2 weeks as described previously.16 Our results showed that overexpression of either miR-335 or miR-363 significantly decreased anchorage-independent growth of BE(2)-C cells, and the number of colonies was decreased to less than 20% in comparison to miR-CON cells (Fig. 2C). Our findings further indicate that miR-335 and miR-363 negatively regulate neuroblastoma cell transformation property.

Figure 2. Cell proliferation, clonogenicity, and anchorage-independent assays.

(A) Cell proliferation was measured by plating cells in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well in RPMI 1640 culture media with 10% FBS and grown for up to 96 h posttransfection. Cell number was assessed daily using Cell-Counting Kit-8. (B) Cell clonogenicity assay was performed by plating cells at low density in 6-well plates (1 × 103 cells/well) and incubated for 10 days. Colonies were fixed and stained with 0.005% crystal violet in 70% methanol for overnight (*= p <0.05 vs. miR-CON). (C) Anchorage-independent growth was examined by culturing cells in 12-well plates (2 × 103 cells/well) with 0.4 % agarose and incubated for 2 weeks prior to staining with 0.005% crystal violet. The colony images were taken with Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR+ Imaging System, and quantitated using Bio-Rad Quantity One Gel Doc version 4.6.9 software (*= p <0.05 vs. miR-CON).

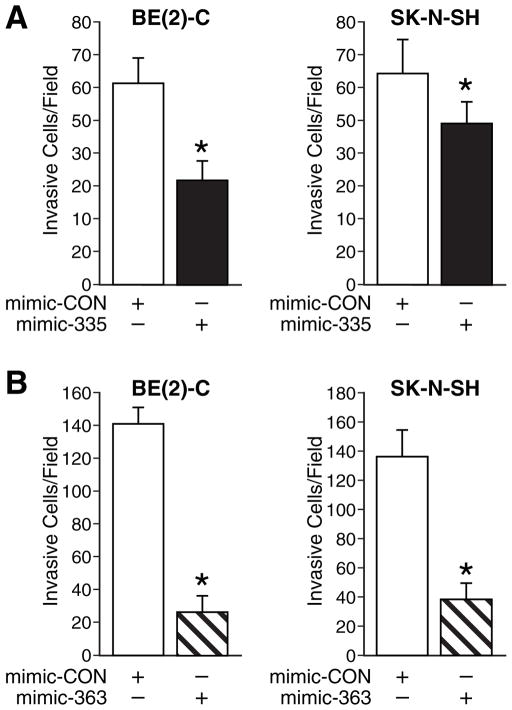

Overexpression of miR-335 or miR-363 suppressed neuroblastoma cell invasion

Our previous studies showed that GRP-R silenced neuroblastoma cells lose their invasiveness.16, 20 Since miR-335 and miR-363 were upregulated in GRP-R silenced BE(2)-C cells, we next wanted to examine the exact functions of miR-335 and miR-363 on cell invasion. We transiently transfected human neuroblastoma cells with microRNA mimics, mimic-335, mimic-363 or control (mimic-CON), and then plated cells in Matrigel in the upper chambers in serum-free media with low chamber containing RPMI with 10% FBS for 48 h. Our results showed that mimics of miR-335 significantly blocked neuroblastoma cell invasion in both BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH cell lines to 52% and 75%, respectively (Fig. 3A). Mimics of miR-363 decreased the cell invasion to 18% and 29%, respectively (Fig. 3B). We demonstrated that miR-335 and miR-363 negatively regulate cell invasiveness in neuroblastoma cells, and hence, upregulation of these miRNA can potentially attenuate and/or prevent neuroblastoma metastasis.

Figure 3. Cell invasion assay.

(A) Cells were transiently transfected with miRNA mimic and control for 24 h, and then were plated in upper chamber of transwell (1 × 105 cells) in serum-free media with the bottom well containing 10% FBS RPMI medium. After 48 h incubation, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with DAPI and counted. miR-335 overexpressing resulted in reduction on cell invasion in both BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH cells (*= p <0.05 vs. mimic-CON). (B) Overexpression of miR-363 decreased cell invasive property in both BE(2)-C and SK-N-SH cells (*= p <0.05 vs. mimic-CON)

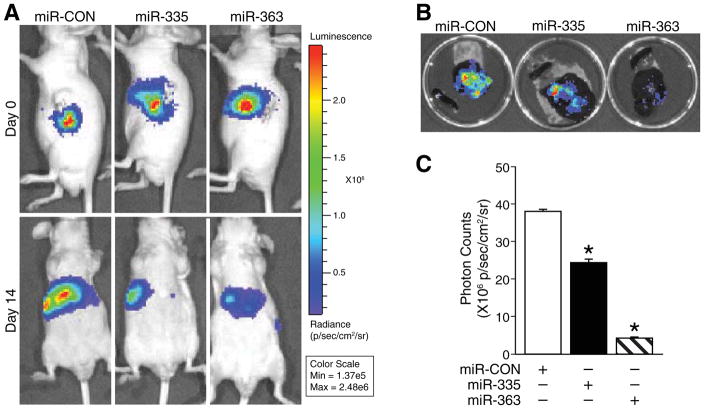

Exogenous expression of miR-335 and miR-363 decreased neuroblastoma liver metastases

Using our well-established murine tumor metastasis model,16, 20 we injected stably-transfected BE(2)-C human neuroblastoma cells, overexpressing luciferase and miR-335 or miR-363 or miR-CON, into spleen of athymic nude mice. Liver metastases were monitored by detecting luminescent signals. Our results showed that mice injected with BE(2)-C cells overexpressing miR-335 and miR-363 showed significantly decreased liver metastasis when compared to controls (Fig. 4A); these gross decreases were also readily observed in dissected whole livers (Fig. 4B). These significant inhibition of liver metastases by miR-335 or miR-363 at day 14 was quantitatively assessed using photon counts (Fig. 4C). Taken together, our in vivo results corroborate in vitro findings that miR-335 and miR-363 critically regulate highly invasive metastatic property of neuroblastoma.

Figure 4. miR-335 and miR-363 inhibited neuroblastoma liver metastasis in vivo.

(A) Bioluminescence images show luciferase-expressing BE(2)-C/miR-CON, miR-335, and miR-363 in an intrasplenic injection murine model. Images were taken on injection day (day 0) and at sacrifice (day 14). Pseudocolor images were adjusted to the same threshold. (B) Representative images of spleen and liver dissected from mice were taken on day 14. (C) Quantitative values of bioluminescence were measured as photon counts using whole body images at day 14. Results were given as the mean ± SEM (n=3 mice per group; *= p <0.05 vs. miR-CON).

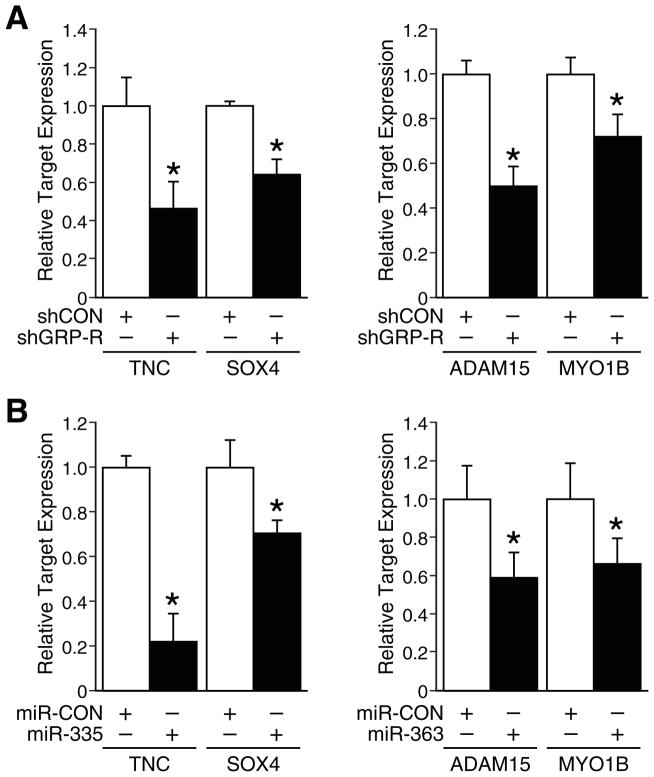

miR-335 and miR-363 downstream targets

To determine the specificity of actions of miR-335 and 363 in neuroblastoma, we next measured the expression of downstream targets of miRNA by QRT-PCR. Progenitor cell transcription factor SOX4 and TNC have been identified as direct targets of miR-335 mediating the suppression on metastasis and migration by miR-335 in breast cancer.4, 10 AMDM15 and MYO1B have been identified as the potential targets of miR-363.21,13 In our study, we also assessed for expression of these downstream targets in stably-transfected BE(2)-C/shCON and shGRP-R cells. Here, we found that TNC and SOX4, the targets of miR-335, were downregulated to 47% and 64%, respectively, in shGRP-R cells (Fig. 5A, left). Similarly, the expressions of ADAM15 and MYO1B, targets of miR-363, were also downregulated to 50% and 72%, respectively, in shGRP-R cells in comparison to shCON cells (Fig. 5A, right). Furthermore, using stably-transfected BE(2)-C/miRNA cells, we confirmed the inhibitions of miR-335 and miR-363 on their targets. The direct targets TNC and SOX4 of miR-335 were downregulated to 22% and 71%, respectively in BE(2)-C/miR-335 in comparison to miR-CON cells (Fig. 5B, left); the direct targets ADAM15 and MYO1B of miR-363 were decreased to 59% and 66%, respectively in BE(2)-C/miR-363 in comparison to miR-CON cells (Fig. 5B, right). Our results suggest that these direct targets of miR-335 and miR-363 may be critical mediators of GRP-R signaling pathway and key regulators of tumorigenesis and metastasis in neuroblastoma.

Figure 5. Downstream targets of miR-335 and miR-363.

(A) Quantitative RT-PCR expression of miR-335 direct targets TNC and SOX4 (left panel) and miR-363 targets ADAM15 and MYO1B (right panel) in BE(2)-C/shCON and shGRP-R cells (*= p <0.05 vs. shCON). (B) Quantitative RT-PCR expression of miR-335 direct targets TNC and SOX4 (left panel) and miR-363 targets ADAM15 and MYO1B (right panel) in BE(2)-C/miR-CON, miR-335 and miR-363 cells (*= p <0.05 vs. miR-CON).

DISCUSSION

A single miRNA is able to target multiple biological networks by regulating its direct targets. Recent studies have identified that several microRNAs have oncogenic or tumor-suppressing functions in human cancers, contributing to malignant progression and specially mediating tumor invasion and metastasis.3 However, the exact functions of miRNAs on neuroblastoma tumorigenicity have not been elucidated. We postulated that alterations in miRNAs might contribute to the characteristic aggressive and metastatic behavior of neuroblastomas. In this study, we show that miR-335 and miR-363 are critical factors mediating GRP-R-induced tumorigenesis and metastasis in neuroblastoma. Using microRNA array, we found that the expressions of miR-335 and miR-363 were significantly upregulated in GRP-R silenced BE(2)-C cells. We also demonstrated the tumor suppressive functions of miR-335 and miR-363 by way of clonogenicity and anchorage-independent cell growth assays as well as in vivo model of liver metastasis. Moreover, we also confirmed predicted targets of miR-335 and miR-363 in our neuroblastoma cell lines. Taken together, our results indicate that miR-335 and miR-363 function as tumor suppressors in GRP-R silenced neuroblastoma.

We previously reported that GRP-R silencing inhibited tumorigenesis and liver metastasis by downregulation of PI3K/Akt pathway.16 We also found that focal adhesion kinase (FAK) critically regulates neuroblastoma tumorigenicity as a downstream target of GRP-R signaling.20 Critical oncogenic and tumor-suppressive functions of miRNAs have recently emerged in cancer biology literature. Hence, we wanted to investigate the potential oncogenic functions of miRNA in GRP-R-mediated tumorigenesis in neuroblastoma. Findings from this study suggest that the increased expressions of miR-335 and miR-363 are potentially involved in attenuated invasive and metastatic properties of shGRP-R neuroblastoma cells.

Recently, miR-335 has been extensively studied in cancer cell biology.4, 9, 10, 22, 23 As an apoptosis permissive factor and a cell cycle suppressor, miR-335 regulates neural progenitor survival and proliferation,22 and low levels of miR-335 lead to proliferation and migration in mesenchymal stem cells.23 miR-335 also contributes to epithelial-to mesenchymal transition and neoplastic development in breast tissue.24 In neuroblastoma, miR-335 directly targets ROCK1, MAPK1 and LRG1, which control neuroblastoma cell invasiveness and are regulated by TGF-β signaling. The expression of miR-335 was suppressed by N-myc directly binding to the promoter of miR-335.9 Previously, we had shown that N-myc expression was decreased by silencing GRP-R in MYCN amplified neuroblastoma cells (PLoS ONE, in press). Therefore, the results from our present study suggest that N-myc could be a mediator between GRP-R and miRNA-335. SOX4 and TNC, which are validated mediator of metastasis in breast cancer,10 could also potentially play critical roles in neuroblastoma tumorigenicity.

Importantly, we demonstrated, for the first time, that miR-363 functions as a tumor suppressor in neuroblastoma. miR-363 is correlated with outcome of gastric cancer,11 Here, we found that miR-363 was significantly upregulated by GRP-R silencing, by which tumorigenesis and metastasis were significantly decreased in neuroblastoma.16 ADAM15 expression is associated with aggressive prostate and breast cancer diseases,12 and as a member of disintegrin proteins, it promotes cell migration by inhibition of integrin-dependent cell adhension.25 MYO1B is a motor protein controlling cell shape and participating cell migration and invasion by alter its motile properties and interaction with actin.26 In this study, we demonstrated that ADAM15 and MYO1B are targets of miR-363 in neuroblastoma, suggesting that miR-363 represses tumor metastasis by inhibiting the expression of ADAM15 and MYO1B in neuroblastoma cells.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that miR-335 and miR-363 are endogenous tumor suppressors, which are regulated by GRP-R signaling in neuroblastoma. Albeit speculative, the aberrant downregulation of miR-335 or miR-363 impairs neuronal crest cell differentiation, thus contributing to neuroblastoma pathogenesis. Therefore, upregulation of miR-335 and miR-363 could potentially reverse the neuroblastoma tumorigenicity by blocking tumor cell transformation, migration and invasion. Thus, a better understanding of miR-335 and miR-363-mediated molecular mechanisms could potentially provide novel therapeutic strategies against highly aggressive metastatic neuroblastoma.

Acknowledgments

Grants: R01 DK61470 from the National Institutes of Health, Rally Foundation for Cancer Research

We thank Karen Martin for her assistance with the manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Presented at the 8th Academic Surgical Congress in New Orleans, LA, Feb 5-7, 2013.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Modak S, Cheung NK. Neuroblastoma: Therapeutic strategies for a clinical enigma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36:307–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida MI, Reis RM, Calin GA. MicroRNAs and metastases--the neuroblastoma link. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:453–4. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.6.11215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynam-Lennon N, Maher SG, Reynolds JV. The roles of microRNA in cancer and apoptosis. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2009;84:55–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Png KJ, Yoshida M, Zhang XH, Shu W, Lee H, Rimner A, et al. MicroRNA-335 inhibits tumor reinitiation and is silenced through genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in human breast cancer. Genes Dev. 2011;25:226–31. doi: 10.1101/gad.1974211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tivnan A, Tracey L, Buckley PG, Alcock LC, Davidoff AM, Stallings RL. MicroRNA-34a is a potent tumor suppressor molecule in vivo in neuroblastoma. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tivnan A, Foley NH, Tracey L, Davidoff AM, Stallings RL. MicroRNA-184-mediated inhibition of tumour growth in an orthotopic murine model of neuroblastoma. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:4391–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foley NH, Bray IM, Tivnan A, Bryan K, Murphy DM, Buckley PG, et al. MicroRNA-184 inhibits neuroblastoma cell survival through targeting the serine/threonine kinase AKT2. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:83. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo J, Dong Q, Fang Z, Chen X, Lu H, Wang K, et al. Identification of miRNAs that are associated with tumor metastasis in neuroblastoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:446–52. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.6.10894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch J, Fay J, Meehan M, Bryan K, Watters KM, Murphy DM, et al. MiRNA-335 suppresses neuroblastoma cell invasiveness by direct targeting of multiple genes from the non-canonical TGF-beta signalling pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:976–85. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tavazoie SF, Alarcon C, Oskarsson T, Padua D, Wang Q, Bos PD, et al. Endogenous human microRNAs that suppress breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2008;451:147–52. doi: 10.1038/nature06487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim CH, Kim HK, Rettig RL, Kim J, Lee ET, Aprelikova O, et al. miRNA signature associated with outcome of gastric cancer patients following chemotherapy. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:79. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuefer R, Day KC, Kleer CG, Sabel MS, Hofer MD, Varambally S, et al. ADAM15 disintegrin is associated with aggressive prostate and breast cancer disease. Neoplasia. 2006;8:319–29. doi: 10.1593/neo.05682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wald AI, Hoskins EE, Wells SI, Ferris RL, Khan SA. Alteration of microRNA profiles in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck cell lines by human papillomavirus. Head Neck. 2011;33:504–12. doi: 10.1002/hed.21475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiao J, Kang J, Cree J, Evers BM, Chung DH. Gastrin-releasing peptide-induced down-regulation of tumor suppressor protein PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten) in neuroblastomas. Ann Surg. 2005;241:684–91. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161173.47717.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S, Hu W, Kelly DR, Hellmich MR, Evers BM, Chung DH. Gastrin-releasing peptide is a growth factor for human neuroblastomas. Ann Surg. 2002;235:621–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiao J, Kang J, Ishola TA, Rychahou PG, Evers BM, Chung DH. Gastrin-releasing peptide receptor silencing suppresses the tumorigenesis and metastatic potential of neuroblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12891–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711861105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang J, Ishola TA, Baregamian N, Mourot JM, Rychahou PG, Evers BM, et al. Bombesin induces angiogenesis and neuroblastoma growth. Cancer Lett. 2007;253:273–81. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franken NA, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman J, van Bree C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2315–9. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freedman VH, Shin SI. Cellular tumorigenicity in nude mice: correlation with cell growth in semi-solid medium. Cell. 1974;3:355–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S, Qiao J, Paul P, O’Connor KL, Evers BM, Chung DH. FAK is a critical regulator of neuroblastoma liver metastasis. Oncotarget. 2012 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sathyan P, Golden HB, Miranda RC. Competing interactions between micro-RNAs determine neural progenitor survival and proliferation after ethanol exposure: evidence from an ex vivo model of the fetal cerebral cortical neuroepithelium. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8546–57. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1269-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tome M, Lopez-Romero P, Albo C, Sepulveda JC, Fernandez-Gutierrez B, Dopazo A, et al. miR-335 orchestrates cell proliferation, migration and differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:985–95. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen TS, Lai RC, Lee MM, Choo AB, Lee CN, Lim SK. Mesenchymal stem cell secretes microparticles enriched in pre-microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:215–24. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu X, Lu D, Scully MF, Kakkar VV. Snake venom metalloproteinase containing a disintegrin-like domain, its structure-activity relationships at interacting with integrins. Curr Med Chem Cardiovasc Hematol Agents. 2005;3:249–60. doi: 10.2174/1568016054368205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laakso JM, Lewis JH, Shuman H, Ostap EM. Myosin I can act as a molecular force bb sensor. Science. 2008;321:133–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1159419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]