Abstract

We present a case of a 27–year–old man with a history of weight loss. A chest x–ray demonstrated hilar lymphadenopathy and he was treated with anti tuberculosis treatment. He noticed a painless left scrotal swelling and a scrotal ultrasound scan raised the possibility of testicular cancer. He underwent an orchidectomy and histology confirmed a testicular sarcoidosis. He was commenced on steroid treatment.

Keywords: testis, sarcoidosis, carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Sarcoidosis is a systemic inflammatory condition characterised by non–caseating epitheloid granulomata that classically affect the chest [1]. Extra–pulmonary granulomata occur in over 75% of cases, but genitourinary sarcoidosis (GUS) is very rare with only 60 cases reported in literature [2, 3]. We present the case of a patient whom presented with weight loss, lymphadenopathy and testicular swelling, that ultimately was secondary to sarcoidosis.

CASE REPORT

In January 2009, a 27–year–old Asian man initially presented to his general practitioner with a 4–month history of weight loss totalling 9 kg and general malaise. Clinical examination revealed cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy. He had no significant past medical history and was not on regular medications. His younger brother was known to have sarcoidosis. Initial blood tests including full blood count (Hb 14.9g/dl, WBC 4.3 109/L, Neutrophils 2.95 109/L, Lymphocytes 0.72 109/L, ESR 9 mm), urea and electrolytes, thyroid and liver function tests only revealed a mildly raised alkaline phosphatase. His HIV test and standard tuberculin test were negative. Interestingly, serum angiotensin converting enzyme level was elevated at 156 U/L (normal range 8–52 U/L), which can serve as an indicator for tuberculosis.

Chest X–ray revealed marked hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. An urgent CT (computed tomography) scan of the thorax, abdomen, pelvis and referral to the respiratory physicians were advised. CT thorax findings raised the possibility of tuberculosis (TB), lymphoma or sarcoidosis. To confirm a diagnosis, the patient underwent a bronchoscopy in February 2009 by the respiratory physicians and the bronchial brush biopsy. A lymph node biopsy was carried out by the General Surgical Team and specimens were sent for tuberculosis culture and histology including haematological malignancies diagnostic services (HMDS).

The differential diagnosis of tuberculosis or lymphoma was considered. While awaiting cultures and pathology results on the above procedures the patient opted to have anti–tuberculosis treatment empirically. Interestingly, all sputum samples and bronchial washings were TB culture negative. His bronchial biopsy showed granulomatous inflammation and raised the possibility of tuberculosis or sarcoidosis. Unfortunately, the lymph node biopsy taken at presentation was not processed in error. In April 2009, he noticed a left sided painless testicular and epididymal swelling. A scrotal ultrasound scan showed a hyperechoic area within the left testis and he was referred to the urology unit. Additionally, despite negative culture findings, on balance, the patient was recommended to complete a six month course of anti–TB treatment.

In May 2009, he complained of diplopia. Fundoscopic examination revealed a mild posterior uveitis. This can be a feature of both tuberculosis and sarcoidosis.

The patient was reviewed in the urology clinic. He gave a 1 year history of progressive left sided testicular and epididymal swelling. This was painless, and he had no urinary symptoms. Examination revealed a firm, non–tender mass, which included the left epididymis and testis.

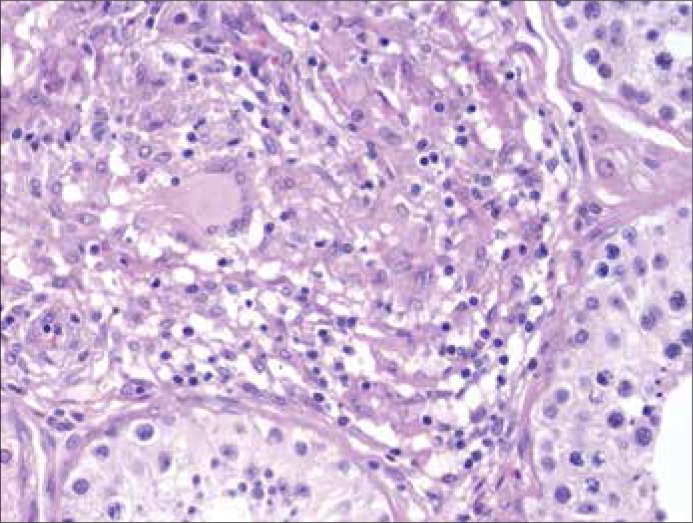

Ultrasound examination revealed a hyper echoic region within the left testis. Of note, βHCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), AFP (alpha–fetoprotein) and LDH (Lactate dehydrogenase) were within normal range. As malignancy could not still be ruled out, the patient underwent a left inguinal orchidectomy and inguinal lymph node biopsy. A frozen section not considered due to clinical and radiological findings. Histology from the above procedure confirmed a diagnosis of sarcoidosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Typical non caseating granuloma with a giant cell in the centre (Hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification x 40).

The patient was commenced on steroid treatment which was continued this for 2 years and is undergoing annual follow–up appointments with the respiratory physicians.

DISCUSSION

A testicular mass has many differential diagnoses including malignancy and, very rarely, sarcoidosis, as in the case described above. Genito–urinary sarcoidosis (GUS) can present with many testicular symptoms from acute pain to painless swelling; with or without constitutional symptoms. Clinical features suggesting a benign diagnosis of GUS include bilateral lesions and Afro–Caribbean ethnicity (three–fold higher incidence of GUS; just 3.5% of total testicular cancer cases) [2–4].

The initial investigations of a patient presenting with a testicular mass would include tumour markers (AFP, βHCG and LDH). A number of different disorders can cause a scrotal mass (Table 1). Sarcoidosis is not generally thought to cause false–positive results for AFP or beta–HCG serum levels. However, there are cases of testicular sarcoidosis with elevated tumour markers in literature [5]; sarcoidosis can cause a raised LDH, which is not a reliable diagnostic test for testicular malignancy [6]. However, AFP and beta–HCG serum levels should be part of the initial assessment of the patient presenting with a testicular mass [6].

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of scrotal masses

| Painless scrotal mass | Painful scrotal mass |

|---|---|

| Testicular tumor | Testicular torsion |

| Hydrocele | Epididymitis |

| Tuberculosis | Inguinal hernia |

| Spermatocele | Testicular tumor (rapidly growing) |

| Varicocele | Trauma (testicular rupture) |

| Paratesticular tumors | |

| Sarcoidosis |

Imaging is central to investigating testicular lesions but poorly differentiates between GUS and malignancy. The most common sonographic finding in GUS is a hyperechoic mass affecting the testis or epididymis, however, as this is not specific to GUS, a coarsened testicular echo–texture is also described [7, 8].

Histological examination remains the most reliable way to confirm sarcoidosis and orchidectomy is the primary radical treatment for testicular mass suggestive of tumour. When deciding to biopsy or remove the affected testis, conserving fertility and testicular function must be considered through sperm storage and avoiding an unnecessary orchidectomy. In one case–series, 45% underwent biopsy, 35% radical orchidectomy/epididymectomy and 20% clinical surveillance [3]. There are various approaches to testicular biopsy but they must consider potential malignant diagnoses, avoiding potential seeding of malignant cells. An inguinal approach open biopsy with intra–operative clamping of the spermatic cord allows intra–operative frozen sections for histological examination (and potential testicle preservation) but can progress to radical orchidectomy if biopsy is equivocal or suggests malignancy [9]. Other centres advocate radical orchidectomy whenever there is a potential diagnosis of testicular malignancy to prevent diagnostic delays or errors [10]. The fact that the lymph node biopsy taken at presentation was lost led to the unnecessary 6 months of empirical TB treatment and the orchidectomy. One can argue that the diagnosis of testicular tumour was unlikely in the presence of enlarged superficial inguinal nodes and the initial clinical picture suggested, from the start, a systemic disease like lymphoma, sarcoidosis or tuberculosis with testicular involvement. In addition, a repeat lymph node biopsy should have been considered, as nodes were superficial and palpable. Corticosteroids are indicated in GUS as they can reduce testicular pain and may improve associated azoospermia [11, 12].

Interestingly, there is a recognized association between sarcoidosis and testicular cancer. The incidence of sarcoidosis in patients with known testicular cancer is approximately 100–fold higher than in a matched population of young Caucasian men [13]. However, just 14% have a diagnosis of sarcoidosis before the development of testicular cancer [14].

CONCLUSIONS

All physicians who manage patients with sarcoidosis should be aware of GUS and the association between sarcoidosis and testicular cancer. In addition, an early discussion at the multi–disciplinary team (surgeon, pathologist and radiologist) should be considered. Furthermore, long–term drug therapy should be initiated after a precise histoplathological diagnosis. We have discussed clinical parameters that indicate the benign diagnosis of GUS but histological examination remains the most reliable way to exclude malignancy.

References

- 1.Hey WD, Shienbaum AJ, Brown GA. Sarcoidosis presenting as an Epididymal Mass. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109:609–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reineks E, MacLennan G. Sarcoidosis of the testis and epidiymis. J Urol. 2008;179:1147. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kodama K, Hasegawa T, Egawa M, Tomosugi N, Mukai A, Namiki M. Bilateral epididymal sarcoidosis presenting without radiological evidence of intrathoracic lesion:review of sarcoidosis involving the male reproductive tract. Int J Urol. 2004;11:345–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2004.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daniels JL, Jr, Stutzman RE, McLeod DG. A comparison of testicular tumours in black and white patients. J Urol. 1981;125:341–342. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thuret R, Cariou G, Aerts J, Cochand–Priollet B. Testicular sarcoidosis with elevated levels of cancer–associated markers. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:6007–6008. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.9861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dick J, Begent R, Meyer T. Sarcoidosis and testicular cancer: a case series and literature review. Urol Oncol. 2010;28:350–354. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart VR, Sidhu PS. The testes: the unusual, the rare and the bizarre. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howlett DC. The testis: the unusual, the rare and the bizarre. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:1019. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Passman C, Urban D, Klemm K, Lockhart M, Kenney P, Kolettis P. Testicular lesions other than germ cell tumours: feasibility of testis–sparing surgery. BJU Int. 2009;103:488–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singer AJ, Gavrell GJ, Leidich RB, Quinn AD. Genitourinary involvement of systemic sarcoidosis confined to testicle. Urology. 1990;35:442–444. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(90)80089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasu T, Lai R, Amzuta I, Nasr M, Lenox R. Sarcoidosis presenting as intrascrotal mass: case report and review. South Med J. 2006;99:995–997. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000224127.65377.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rees DA, Dodds AL, Rathbone N, Davies JS, Scanlon MF. Azoospermia in testicular sarcoidosis is an indication for corticosteroid therapy. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1672–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.07.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rayson D, Burch PA, Richardson RL. Sarcoidosis and testicular carcinoma. Cancer. 1998;83:337–343. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980715)83:2<337::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paparel P, Devonec M, Perrin P, Ruffion A, Decaussin–Petrucci M, Akin O, et al. Association between sarcoidosis and testicular carcinoma: a diagnostic pitfall. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2007;24:95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]