Abstract

Chronic smoking has been linked with alterations in endogenous pain regulation. These alterations may be pronounced when individuals quit smoking because nicotine withdrawal produces a variety of psychological and physiological symptoms. Smokers interested in quitting (n=98) and nonsmokers (n=37) completed a laboratory session including cold pressor (CPT) and heat thermal pain. Smokers set a quit date and completed the session after 48 hours of abstinence. Participants completed the pain assessments once post rest and once post stress. Cardiovascular and nicotine withdrawal measures were collected. Smokers showed blunted cardiovascular responses to stress relative to nonsmokers. Only nonsmokers had greater pain tolerance to CPT post stress than post rest. Lower systolic blood pressure was related to lower pain tolerance. These findings suggest that smoking withdrawal is associated with blunted stress response and increased pain sensitivity.

Keywords: Pain, Stress-induced analgesia, Nicotine dependence, Smoking, Cardiovascular

Introduction

Cessation of smoking leads to a nicotine withdrawal syndrome which includes a variety of subjective and physiological symptoms such as anxiety, depression, irritability, impatience, hunger, disturbance in sleep, difficulty concentrating, and decrease in heart rate (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). These symptoms may peak within the first week of cessation and linger for two to four weeks (Hughes, 2007) or longer (Gilbert et al., 2002). However, recent reports show that withdrawal symptoms may start to develop within several hours after quitting smoking (Hendricks, Ditre, Drobes, & Brandon, 2006; Morrell, Cohen, & al’Absi, 2008), and the symptom severity as well as stress-related biomarkers assessed during this initial phase of quitting are predictive of relapse (al’Absi, Hatsukami, & Davis, 2005; Piasecki, Fiore, & Baker, 1998). These findings suggest the mediating role of psychophysiological processes during the early stage of nicotine withdrawal in cessation outcomes.

Nicotine withdrawal may influence neurophysiologic mechanisms linked with pain. Growing evidence suggests smokers may take up cigarettes to manage pain, and pain may facilitate smoking (Ditre, Brandon, Zale, & Meagher, 2011). Acute nicotine intake suppresses pain (Fertig, Pomerleau, & Sanders, 1986; Jamner, Girdler, Shapiro, & Jarvik, 1998; Kanarek & Carrington, 2004; Pomerleau, Turk, & Fertig, 1984; Waller, Schalling, Levander, & Edman, 1983) via activation of endogenous opioid, serotonergic, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA), and sympatho-adreno-medullary (SAM) systems (al’Absi, 2006; Benowitz, 1988; Pomerleau, 1992; Shi, Weingarten, Mantilla, Hooten, & Warner, 2010). Nicotine stimulates the SAM which results in the release of catecholamines, activating the cardiovascular system. These processes are linked with pain suppression (al’Absi, Buchanan, and Lovallo, 1996; al’Absi, Petersen, and Wittmers, 2000, al’Absi, Nakajima, and Grabowski, 2013; Fillingim and Maixner, 1996; France and Stewart, 1995). It is possible that nicotine withdrawal may make abstinent smokers more sensitive to physical discomfort.

The link between elevated blood pressure and pain suppression has been reported (al’Absi & Petersen, 2003; al’Absi, Buchanan, & Lovallo, 1996; al’Absi, Buchanan, Marrero, & Lovallo, 1999; Ghione, 1996). Interestingly, dysregulations in stress responses have been reported in habitual smokers (al’Absi, Wittmers, Erickson, Hatsukami, & Crouse, 2003; Kirschbaum, Strasburger, & Langkrar, 1993; Roy, Steptoe, & Kirschbaum, 1994; Straneva, Hinderliter, Wells, Lenahan, & Girdler, 2000). These alterations have been proposed as one determinant of enhanced pain sensitivity among this population (Girdler et al., 2005). Consistent with this possibility, our group recently examined stress response and SIA in habitual smokers who were minimally deprived from smoking (al’Absi, Nakajima, & Grabowski, 2013) and showed attenuated physiological responses to stress as well as diminished SIA relative to nonsmokers. The current study was conducted to examine this model in abstinent smokers during the initial stage of a quit attempt. We hypothesized that, in addition to attenuated cardiovascular responses to stress, abstinent smokers would show enhanced pain sensitivity and diminished SIA as compared with nonsmokers.

Method

Participants

This study is part of a larger project focusing on stress and smoking relapse. Detailed description of participant recruitment has been published elsewhere (al’Absi et al., 2013). In short, smokers and nonsmokers were recruited in two cities in Minnesota. Phone screening and on-site screening were conducted. The purpose of the on-site screening was to assess if potential participants were eligible to the study. Participants were included if they: 1) had smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day for at least two years with a strong motivation to quit, 2) had no current major physical disease or psychiatric disorder, 3) had no routine use of prescribed medications with an exception of contraceptives, 4) weighted within ±30% of Metropolitan Life Insurance norms (i.e., body mass index between 18 and 30), and 5) consumed two or less alcohol drinks/day. Eligible participants read and signed a consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Minnesota. After that, they were asked to complete a battery of questionnaires (see below) and set up an appointment for subsequent laboratory sessions.

Although participants included in this study were also included in the previous study (al’Absi et al., 2013), all data included in the current report are from the second wave of data collection and do not overlap with the previous report. Smokers were smoking on their own pace when they completed the first session (al’Absi et al., 2013). These smokers completed this study after they quit smoking. In parallel with testing of smokers, a comparison group of nonsmokers completed both protocols in the same sequence. The order of ad libitum-abstinence protocol was fixed. We avoided using a counterbalanced design of smoking status because the smokers included here were interested in smoking cessation. If we were to counterbalance ad libitum and abstinence conditions, one group of participants would need to go back to smoking after having already quit. Such protocol would not be acceptable from human subject protection point of view, and would also likely influence the study results.

Upon completion of the first laboratory session (al’Absi et al., 2013), 12 individuals (11 smokers and 1 nonsmoker) did not return to the current study. Furthermore, data from 7 smokers were excluded in the current analyses because they had CO levels greater than 8 ppm. Taken together, a total of 98 smokers (46 women) and 37 nonsmokers (18 women) were included in the present study. The number of smokers was larger than that of nonsmokers because this study was part of a larger project which investigated psychobiological mechanisms of stress, smoking, and smoking relapse (al’Absi et al., 2013).

Apparatus and Measures

Physiological and biochemical measures

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP, DBP) and heart rate (HR) were collected by a Dinamap oscillometric monitor system (Critikon, Tampa, Florida). Cotinine were measured using Salivette® tubes (Sarstedt, Rommelsdorf, Germany), and the levels were measured by EIA (DSL, Sinsheim, Germany) with inter- and intra-assay variations below 12%. MicroCO™ monitors (Micro Direct Inc., Auburn, Maine) were used to collect levels of carbon monoxide (CO). Salivary cotinine and CO were used to test abstinence of smoking.

Pain measures

We used two types of pain assessment, the cold pressor test (CPT) and thermal heat pain induction (al’Absi et al., 2013). The CPT consisted of a one-gallon container filled with ice water (0–1°C), and pain tolerance was measured (maximum of 240 seconds). For the heat pain assessment, we used a computer-operated 2 cm2 Peltier contact thermode. Heat stimuli were administered to the skin on the left volar forearm. Temperature of the heat was monitored by a contactor-contained thermistor (Medoc TSA 2001, Minneapolis, MN). The thermode was reset to 35°C. Heat pain threshold and tolerance were assessed using an ascending method of limits with a staircase ramp of 1 °C/s. We instructed participants to press a button at the point when they first perceived the stimulus as painful (pain threshold) and once again at the point when they were intolerable to the stimuli (pain tolerance). This procedure was repeated for four sets and the average of the last three trials was calculated to obtain levels of pain threshold as well as tolerance. The position of the thermode was changed by one centimeter after each trial to control for habituation effect. The maximum temperature was 52°C. We entered this value in case the participant did not report pain threshold or tolerance within a trial. Immediately after each pain test, a short version of McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ; (Melzack, 1975) was given to assess global pain experience.

Mood and withdrawal measures

The Revised Subjective States Questionnaire (SSQ; (Lundberg & Frankenhaeuser, 1980) was used to assess positive affect (cheerfulness, contentedness, calmness, controllability, and interest) and distress (anxiety, irritability, impatience, and restlessness). Each item had a 7-point scale with endpoints anchored by “Not at all” and “Very Strong.” Smokers completed Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS: (Hughes & Hatsukami, 1986), which included items such as irritability, anger, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, depressed/sad mood, and hunger, for the assessment of withdrawal severity. The item “craving” was analyzed separately from other withdrawal symptoms because studies have shown that these two are conceptually different (Hughes & Hatsukami, 1986). The brief version of the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU-B; (Cox, Tiffany, & Christen, 2001; Tiffany & Drobes, 1991) was used to assess smoking urges (factor 1: appetitive urges; factor 2: aversive urges).

Other measures

During the onsite screening or before the laboratory session, participants were asked to complete forms regarding demographic questionnaire (e.g., age, years of education), psychosocial stress (the Perceived Stress Scale; PSS; (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983), and mood disturbance (the Profile of Mood State Questionnaire; POMS; (McNair, Lorr, & Droppleman, 1992). Smokers also completed questionnaires about their smoking history and levels of dependence to nicotine (Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence; FTND;(Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991).

Procedures

Participants were tested individually. The participant was instructed to refrain from caffeine and alcohol for 4 hours and exercise for 24 hours prior to the scheduled session. Smokers were required to be abstinent for 48 hours, the first period of their quit attempt. Laboratory sessions were scheduled between noon and 2pm to control for diurnal fluctuations in hormonal measures. Upon arrival, the participant was greeted and seated in a comfortable chair in the laboratory testing room. A saliva sample was collected for cotinine measurement and expired CO was assessed. The participant was if he or she admitted smoking during the past 48 hours. After that a blood pressure cuff was then placed on the participant.

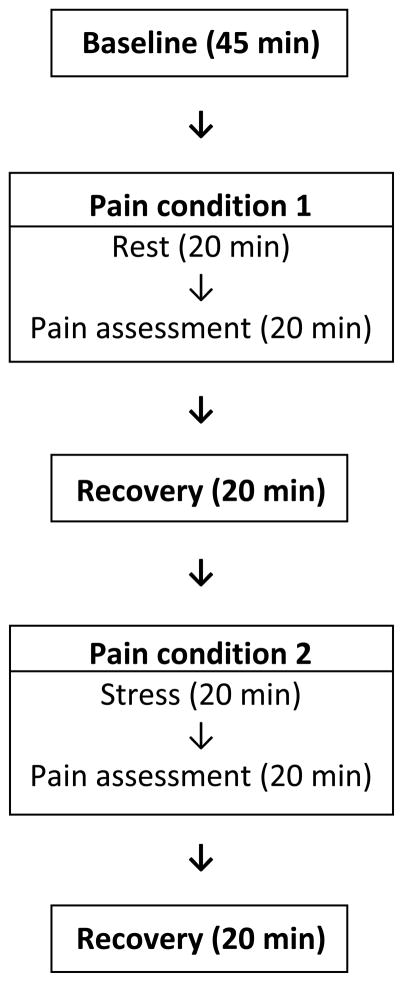

The experimental protocol was the same as in the previous study (al’Absi et al., 2013) with the exception of recruiting smokers who have abstained from smoking for 48 hours. Briefly the protocol consisted of: 1) 45 minute baseline, 2) rest/stress - pain, 3) 20 min rest, 4) rest/stress - pain, and 5) 20 min rest (see Figure 1). There were two pain conditions: one was administered after a 20 minute resting period (i.e., rest-pain condition) and the other was administered after behavioral challenges which included a public speaking (4 min preparation and 4 min delivery phases) and a mental arithmetic (10 min; stress-pain condition). The order of pain conditions were counterbalanced across participants. For example, one group of participants completed the rest-pain condition first and the other group completed the stress-pain condition first. The participant watched a nature video clip during the initial baseline and post-pain resting periods. Cardiovascular measures (SBP, DBP, HR) were assessed every 5 minutes during the last 20 minutes of the baseline period, every 2 min during each stressor, and every 5 minutes during the rest periods. Self-report measures of mood and nicotine withdrawal were collected at the end of baseline, stress, and recovery periods. The participant was paid approximately 20 U.S. dollars per hour for their participation.

Figure 1.

Graphic description of the study design. Note: pain assessment was conducted twice in each session, after rest (pain condition 1) and after stress (pain condition 2). The order of condition (rest–pain vs. stress–pain) was counterbalanced across subjects.

Data Reduction and Analysis

One-hundred and thirty five participants (64 women) completed stress tasks and CPT, and 82 individuals (46 women) completed thermal heat pain test as well. Pain measures and MPQ scores were analyzed using 2 smoking group (smoker, nonsmoker) × 2 sex (male, female) × 2 pain condition (rest-pain, stress-pain) multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVAs) including order of task (rest-pain order first or stress-pain order first) and site as covariates. Site was included as a covariate since the primary reason of the data collection from two study locations was to maximize the sample size rather than to compare differences in target variables between the two sites. For cardiovascular measures, mean values were calculated for baseline, stress, and post-stress recovery periods. SBP, DBP, and HR, and positive affect and distress were analyzed by 2 smoking group × 2 sex × 3 time (baseline, stress, recovery) MANCOVAs. Withdrawal symptoms and smoking urges measured in smokers were analyzed by 2 sex × 3 time (baseline, stress, recovery) MANCOVAs. Wilk’s lambda was used for these analyses and Bonferroni adjustments were applied to post-hoc multiple comparisons where appropriate. In addition, correlational analyses were conducted to examine the extent to which physiological as well as mood and withdrawal measures were associated with pain sensitivity. A series of analysis of variance (ANOVAs) with smoking group and sex as between factors as well as chi-square tests were conducted to analyze measures of the first hormonal samples collected during the beginning of the laboratory session, demographic variables, and trait mood levels (PSS and POMS). One-way ANOVAs using sex as an independent factor were conducted to examine sex differences in smoking history (e.g., average number of cigarettes per day). P values less than .05 were considered significant. SPSS version 19 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used for data analysis. Because of occasional missing data, variations existed between sample size and degrees of freedom for the reported variables.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Body mass index (BMI), average hours of sleep per day, and marital status were comparable between smokers and nonsmokers (ps > .18: see Table 1). Relative to nonsmokers, smokers were older (F(1, 131) = 3.79, p = .05, η2 = .03) and were more likely to be Caucasian (χ2 = 6.27, p < .05), and reported fewer years of education and greater caffeine consumption (Fs (1, 127) > 7.84, ps < .01, η2 > .06). Also, smokers reported greater past psychiatric history (χ2 = 16.0, p < .001), and stress levels (PSS) and mood disturbance (POMS) than nonsmokers (Fs (1, 131) > 10.1, ps<.01, η2 > .07). Male and female smokers were comparable with respect to smoking history (ps > .33). Smoking status (smoker, nonsmoker) was not associated with the phase of menstrual cycle (follicular, luteal) in women (p = .75). Thus, in addition to the MANCOVA models described above, we conducted following models. We first included all demographic variables that differed across smoking groups. Then, demographic variables that did not make significant contribution (p > .05) were taken out from the model, except the psychiatric history variable. This was because of research showing comorbidity of psychiatric symptoms with pain experience (see Ditre et al., 2011 for a review). Therefore, for each dependent measure, the final MANCOVA model included significant covariates and the psychiatric history variable.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics, smoking variables, and biochemical measures.

| Nonsmokers (n=37) | Smokers (n=98) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Men (n=19) | Women (n=18) | Men (n=52) | Women (n=46) | |

| Age (years)a | 26.5 (2.7) | 34.8 (2.8) | 34.9 (1.7) | 35.4 (1.8) |

| BMI | 24.5 (1.0) | 24.2 (1.0) | 26.1 (0.6) | 24.8 (0.7) |

| Education (years)a | 16.1 (0.7) | 15.5 (0.7) | 14.0 (0.4) | 14.5 (0.4) |

| Caffeine (drinks/day)a | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.3) |

| Sleep (hours per day) | 7.5 (0.2) | 7.1 (0.3) | 7.0 (0.1) | 7.3 (0.2) |

| Single (%) | 83.3 | 55.6 | 62.7 | 52.2 |

| Caucasian (%)a | 57.9 | 72.2 | 84.6 | 84.4 |

| Past psychiatric history (%)a | 10.5 | 5.6 | 38.5 | 52.2 |

| Mood disturbance (POMS)a | 8.4 (6.4) | 12.6 (6.6) | 29.8 (3.9) | 26.7 (4.1) |

| Perceived stress (PSS)a | 16.2 (1.1) | 16.9 (1.2) | 19.1 (0.7) | 19.8 (0.7) |

| Cigarettes (per day) | n/a | n/a | 18.7 (0.9) | 17.9 (1.0) |

| Duration (years) | n/a | n/a | 12.1 (1.3) | 10.5 (1.4) |

| Previous quit attempts | n/a | n/a | 5.6 (1.5) | 7.0 (1.5) |

| Motivation to quit (1 not at all - 7 very strong) | n/a | n/a | 5.8 (0.1) | 5.7 (0.2) |

| FTND | n/a | n/a | 5.6 (0.3) | 5.2 (0.3) |

| CO (ppm) | n/a | n/a | 4.1 (0.3) | 3.6 (0.3) |

| Cotinine (ng/mL) | n/a | n/a | 44.9 (5.5) | 32.3 (6.2) |

Entries show mean and standard error. Note: BMI: body mass index; POMS: Profile of Mood State questionnaire; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; FTND: Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence; CO: carbon monoxide.

Smoking group effect was significant.

Verification of Smoking Abstinence

A 2 sex × 2 session (on-site screening, abstinent laboratory session) MANOVA conducted in smokers found that CO (F(1, 96) = 259, p < .001, η2 = .73) and cotinine (F(1, 80) = 59, p < .001, η2 = .43) levels during the abstinent session were lower than those in the ad lib session (see Table 1). Low levels of CO prior to the study session also suggest compliance with abstinence period. Cotinine levels after 48-hour abstinence were approximately 75% less than their pre-cessation levels, which is consistent with studies on cotinine half-life (Curvall, Elwin, Kazemi-Vala, Warholm, & Enzell, 1990). No sex differences were observed in these measures (ps > .83).

Mood and Withdrawal Severity

Distress increased and positive affect decreased in response to stress as indicated by main effects of time (Fs(2, 128) > 9.05, ps < .001, η2 > .12) followed by multiple comparison tests (ps < .05), and smokers reported greater distress and lower positive affect than nonsmokers as indicated by a main effect of smoking group (Fs (1, 129) > 9.58, ps < .01, η2 = .07; see Table 2). Findings in distress remained significant after including additional covariates (past psychiatric history; ps < .01). In smokers, reported withdrawal symptoms increased in response to stress (time effect: F(2, 93) = 23.2, p < .001, η2 = .33; multiple comparison tests p < .001) and QSU-B factor 1(appetitive urges) and factor 2 (aversive urges) scores decreased during recovery relative to baseline (time effect: Fs(2, 93) > 4.81, ps < .05, η2 > .09; multiple comparison tests: ps < .01), although sex differences were not observed (ps > .66: see Table 2).

Table 2.

Mood and withdrawal measures

| Nonsmokers | Smokers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Distressab | ||||

| baseline | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.3) | 6.4 (0.8) | 6.3 (0.9) |

| stress | 3.3 (1.3) | 5.4 (1.4) | 8.3 (0.8) | 8.1 (0.9) |

| recovery | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.7 (1.4) | 7.1 (0.8) | 6.7 (0.9) |

| Positive affecta | ||||

| baseline | 15.8 (1.6) | 16.5 (1.7) | 14.2 (1.0) | 12.7 (1.1) |

| stress | 16.9 (1.5) | 14.5 (1.6) | 12.4 (0.9) | 10.6 (1.0) |

| recovery | 19.1 (1.6) | 17.4 (1.7) | 14.4 (1.0) | 12.8 (1.1) |

| MNWSa | ||||

| baseline | n/a | n/a | 8.8 (1.1) | 8.5 (1.2) |

| stress | n/a | n/a | 11.2 (1.1) | 11.3 (1.2) |

| recovery | n/a | n/a | 10.1 (1.0) | 9.0 (1.1) |

| Craving (MNWS) | ||||

| baseline | n/a | n/a | 3.2 (0.3) | 2.9 (0.3) |

| stress | n/a | n/a | 2.7 (0.3) | 3.0 (0.3) |

| recovery | n/a | n/a | 2.8 (0.3) | 2.8 (0.3) |

| QSU-B F1a | ||||

| baseline | n/a | n/a | 21.4 (1.5) | 22.4 (1.7) |

| stress | n/a | n/a | 20.7 (1.5) | 21.9 (1.7) |

| recovery | n/a | n/a | 20.1 (1.5) | 19.5 (1.7) |

| QSU-B F2a | ||||

| baseline | n/a | n/a | 11.0 (1.0) | 12.1 (1.1) |

| stress | n/a | n/a | 10.4 (1.0) | 11.3 (1.1) |

| recovery | n/a | n/a | 9.9 (0.9) | 9.7 (1.0) |

Entries show mean and standard error of mood and withdrawal measures in response to stress, adjusting for site site and task order. Note. MNWS: Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale; Craving: this item was analyzed separately from MNWS; QSU-B: Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (Factor 1: appetitive urges; Factor 2: aversive urges).

Time effect was significant.

Smoking group effect was significant.

Physiological Measures

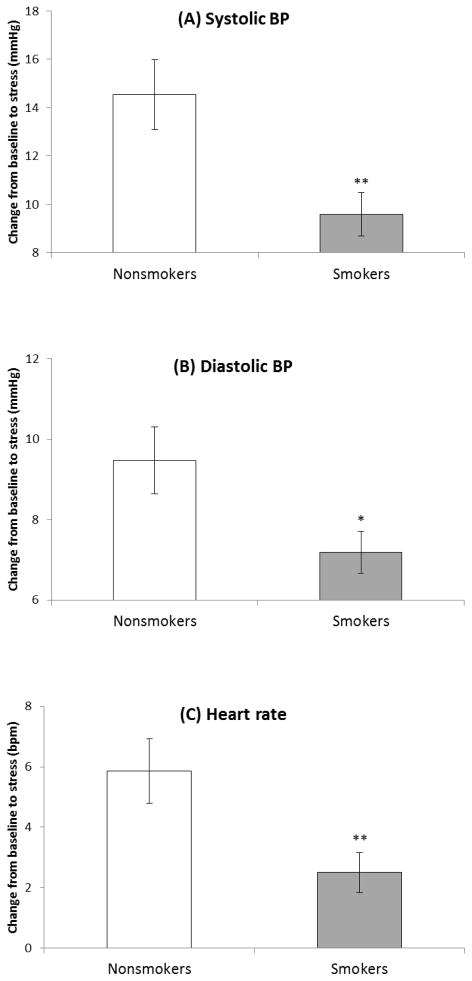

Significant smoking group × time interactions were obtained in SBP (F(2, 128) = 4.49, p < .05, η2 = .07), DBP (F(2, 128) = 5.45, p < .01, η2 = .08), and HR (F(2, 128) = 3.68, p < .05, η2 = .05; see Table 3). Analysis of changes scores examining stress reactivity (differences in levels during baseline and stress periods) found significant smoking group differences in all cardiovascular measures, reflecting diminished response in abstinent smokers relative to nonsmokers (Fs(1, 129) > 5.43, ps < .05, η2 > .04; see Figure 2). Men exhibited greater SBP (F(1, 129) = 39.7, p < .001, η2 = .24) and HR (F(2, 129) = 12.4, p < .01, η2 = .09) than women as indicated by main effects of sex. A smoking group × time interaction found in SBP and HR diminished when additional covariates were included (SBP: past psychiatric history and age; HR: past psychiatric history; ps < .08). In contrast, a significant smoking group × sex × time interaction emerged in DBP with additional covariates (past psychiatric history and age; F(2, 126) = 3.26, p < .05, η2 = .05), suggesting slower recovery in female smokers as compared with female nonsmokers (p < .01).

Table 3.

Cardiovascular measures

| Nonsmokers | Smokers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| SBP (mmHg)abc | ||||

| Baseline | 112.5 (2.3) | 103.7 (2.3) | 116.2 (1.4) | 103.9 (1.5) |

| Stress | 128.6 (2.8) | 116.7 (2.9) | 127.3 (1.7) | 112.0 (1.8) |

| Recovery | 115.1 (2.3) | 103.3 (2.4) | 116.1 (1.4) | 105.4 (1.5) |

| DBP (mmHg)ac | ||||

| Baseline | 61.7 (1.7) | 64.3 (1.8) | 66.6 (1.0) | 62.3 (1.1) |

| Stress | 72.5 (1.8) | 72.4 (1.9) | 74.7 (1.1) | 68.6 (1.2) |

| Recovery | 65.5 (1.9) | 64.0 (2.0) | 68.7 (1.2) | 64.8 (1.3) |

| HR (bpm)abc | ||||

| Baseline | 64.6 (2.0) | 71.8 (2.1) | 65.7 (1.2) | 68.2 (1.3) |

| Stress | 69.3 (2.1) | 78.8 (2.2) | 68.2 (1.3) | 70.7 (1.4) |

| Recovery | 59.1 (1.9) | 66.3 (1.9) | 58.6 (1.1) | 62.4 (1.2) |

Entries show mean and standard error of cardiovascular and hormonal measures in response to stress, adjusting for site and task order. Note. ACTH: adrenocorticotropic hormone; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HR: heart rate; bpm: beats per minute.

Time effect was significant.

Sex effect was significant..

Smoking group × time interaction was significant.

Figure 2.

Cardiovascular response to acute laboratory stress. Bars indicate mean and line bars indicate standard error. Note: Response was defined as the difference between rest and stress periods. *p< .05. **p<.01.

Pain measures and SIA

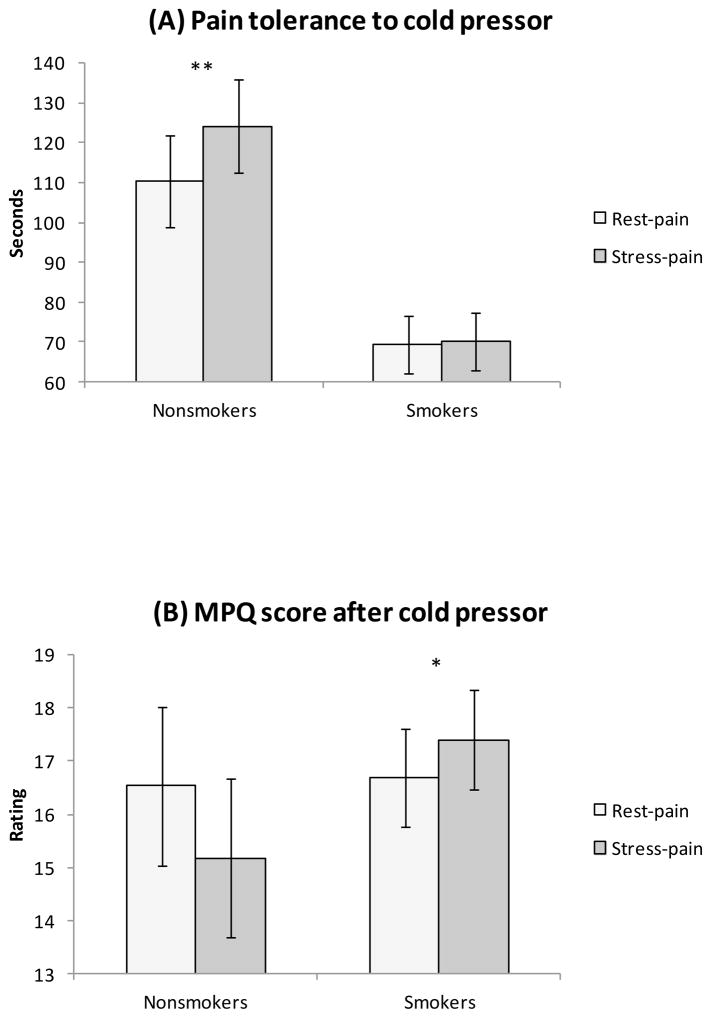

Seven smokers (7%) and 9 nonsmokers (24%) reached maximum tolerance (i.e., 240 sec) to CPT after rest (χ2 = 7.57, p < .01) while 8 smokers (8%) and 12 nonsmokers (32%) reached maximum tolerance to CPT post stress (χ2 = 11.9, p < .01). Pain tolerance to CPT was lower in smokers than in nonsmokers (group effect: F(1, 125) = 12.6, p < .01, η2 = .09) and in women than in men (sex effect: F(1, 125) = 12.2, p < .01, η2 = .09; see Table 4). In addition, pain tolerance after stress was higher than that after rest (pain condition effect: F(1, 125) = 7.92, p <.01, η2 = .06). These findings were qualified by a significant smoking group × pain condition interaction (F(1, 125) = 6.58, p < .05, η2 = .05). Analyses conducted in each smoking group found that while nonsmokers showed enhanced tolerance after stress than after rest (p = .02), this was not found in smokers (p = .95; see Figure 3). Also, there was a significant smoking group × pain condition effect in MPQ scores after CPT (F(1, 129) = 10.0, p < .01, η2 = .07); smokers tended to report greater pain after stress than after rest (p < .05) whereas this was not the case with nonsmokers (p = .10; see Figure 3). These findings remained significant after taking into account additional covariates (past psychiatric history; ps < .05).

Table 4.

Pain measures

| Nonsmokers | Smokers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| CPT | ||||

| Pain tolerance (sec)abcd | ||||

| Rest-pain | 129.8 (16.4) | 91.1 (16.6) | 94.3 (9.8) | 44.5 (10.8) |

| Stress-pain | 150.7 (16.4) | 97.6 (16.6) | 94.6 (9.8) | 45.6 (10.8) |

| MPQd | ||||

| Rest-pain | 14.3 (2.1) | 18.8 (2.1) | 16.0 (1.2) | 17.4 (1.4) |

| Stress-pain | 13.6 (2.1) | 16.7 (2.1) | 16.9 (1.2) | 17.9 (1.4) |

| Thermal heat pain | ||||

| Pain threshold (°C) | ||||

| Rest-pain | 43.5 (1.0) | 43.8 (0.9) | 44.5 (0.6) | 44.6 (0.5) |

| Stress-pain | 43.1 (1.0) | 44.2 (0.9) | 44.5 (0.6) | 44.3 (0.5) |

| Pain tolerance (°C) | ||||

| Rest-pain | 49.1 (0.6) | 48.2 (0.5) | 49.4 (0.4) | 48.6 (0.3) |

| Stress-pain | 48.9 (0.6) | 48.4 (0.5) | 49.6 (0.4) | 48.6 (0.3) |

| MPQ | ||||

| Rest-pain | 16.9 (2.7) | 17.9 (2.4) | 15.6 (1.6) | 17.5 (1.5) |

| Stress-pain | 15.8 (2.7) | 18.0 (2.5) | 15.9 (1.7) | 17.8 (1.5) |

Entries show mean and standard error of pain measures after stress or rest, adjusting for site and task order. Note: CPT: cold pressor test; MPQ: McGill Pain Questionnaire.

Smoking group effect was significant.

Sex effect was significant.

Pain condition effect was significant.

Group × pain condition interaction was significant.

Figure 3.

Group differences in pain measures. Bars indicate mean and line bars indicate standard error. Note: (A) Significant smoking group × condition interaction in pain tolerance to CPT reflected stress-induced analgesia (SIA) in nonsmokers but not in smokers. (B) Significant smoking group × condition effect in MPQ after CPT reflected a tendency of lack of SIA in smokers. *p< .05. **p=.02.

In contrast, no smoking group, sex, pain condition differences were observed in thermal heat pain measures (ps > .08; see Table 4), with one exception of greater heat pain tolerance observed in men than in women after including additional covariates (past psychiatric history and age; p < .01). Two participants (1 smoker (2%), 1 nonsmoker (5%)) reached maximum tolerance to heat pain (i.e., 52 °C) after rest as well as after stress, respectively.

Stress Response and Pain Sensitivity

Greater SBP during stress was positively correlated with greater tolerance to CPT (r = .24, p < .01). Lower positive affect during stress (r = .26, p < .01) and greater distress during baseline and stress (rs > −.17, ps < .05) were related to lower CPT tolerance. Greater distress was linked with greater MPQ scores after CPT (rs > .39, ps < .001). In smokers, withdrawal symptoms during baseline and stress (rs > .38, ps < .001), QSU-B factor 1 during baseline, and factor 2 during baseline and stress (rs > .22, ps < .05) were positively correlated with MPQ scores after CPT. Higher SBP during baseline was associated with higher tolerance to heat pain (r = .25, p < .01). Withdrawal symptoms during baseline and stress were positively correlated with MPQ scores after heat pain (rs > .43, ps < .01).

Discussion

The current study found that 1) smokers going through withdrawal had lower pain tolerance to CPT than nonsmokers, 2) nonsmokers showed SIA in CPT whereas this was not observed in smokers, 3) smokers exhibited attenuated cardiovascular responses to stress as compared with nonsmokers, 4) lower SBP was associated with lower pain tolerance, and 5) acute stress was associated with increased withdrawal symptoms, and these symptoms were positively correlated with pain experience. These findings confirm our hypothesis that abstinent smoking may be associated with dysregulated endogenous pain modulation.

The findings of positive association between withdrawal severity and pain after CPT and after heat pain suggest that nicotine withdrawal may contribute to enhanced pain perception (Anderson et al., 2004; Mousa, Aloyo, & Van Loon, 1988; Nesbitt, 1973; Silverstein, 1982). Also in this study, SIA (CPT) was observed in nonsmokers but not in smokers, and pain experience (CPT) was greater after stress than after rest in smokers but not in nonsmokers. These finding were not observed during ad libitum smoking (al’Absi et al., 2013). While direct comparisons were not available, it is possible that pain sensitivity to CPT is pronounced during nicotine withdrawal. On the other hand, the previous study found SIA in response to heat pain only among nonsmokers whereas this was not replicated in the present study. Although underlying mechanisms are not clear, it is possible that SIA is influenced by smoking status and mode of pain induction (Girdler et al., 2005).

Mechanisms of smoking and stress-mediated pain suppression should be elucidated. Acute nicotine administration (Fertig et al., 1986; Jamner et al., 1998; Kanarek & Carrington, 2004; Pomerleau et al., 1984; Waller et al., 1983) and acute stress (al’Absi, Petersen, & Wittmers, 2002; al’Absi, Petersen, & Wittmers, 2000; al’Absi & Petersen, 2003; al’Absi et al., 1996) stimulate central pathways associated with analgesia; however, chronic nicotine exposure may desensitize these mechanisms (Girdler et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2010). Repeated exposure to drugs including nicotine has been shown to be related to deficiency in beta endorphin (Girdler et al., 2005; Scanlon, Lazar-Wesley, Grant, & Kunos, 1992). Animals treated chronically with nicotine showed diminished hypoalgesia in response to morphine, reflecting nueroadaptation in the opioid system due to prolonged nicotine intake (Zarrindast, Khoshayand, & Shafaghi, 1999). Also, reports show maladaptive physiological adjustments to stress in habitual smokers (al’Absi et al., 2003; al’Absi et al., 2013; Kirschbaum et al., 1993; Roy et al., 1994; Straneva et al., 2000). Habitual tobacco use may down-regulate central and peripheral mechanisms that mediate anti-nociceptive effects of nicotine. This study was among the first to report a lack of SIA in smokers who were deprived of cigarettes for 48 hours.

The results of the current study may help better understand the complex association of smoking and pain in light of observations that nicotine has both antinociceptive properties and plays active role in worsening chronic pain conditions (Ditre et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2010). One possibility is that acute analgesic effects of nicotine is diminished over time with chronic tobacco use through neuroadaptations in central pain modulating mechanisms. This may result in increased sensitivity to withdrawal symptoms and physical discomfort. These vulnerable smokers, however, may take up cigarettes to cope with negative symptoms. Recent studies have shown increased pain perception as a motivator of cigarette use (Ditre & Brandon, 2008) and as a predictor for early smoking relapse (Nakajima & al’Absi, 2011). It is possible that increased pain sensitivity (due to dysregulations in the opioid system because of regular smoking) could be a motivator of cigarette use to manage pain. The other direction is also plausible: individuals who are predisposed to abuse substance are sensitive to pain. The extent to which smoking-related dysregulations in endogenous pain mechanisms predict severity of withdrawal symptoms and motives for tobacco use has not been directly examined.

We cannot draw conclusions about causal directions as we used cross-sectional design. Thus, whether chronic smoking disrupts pain regulatory systems or heightened sensitivity to pain predisposes an individual to smoke is not clear. Inclusion of two smoking conditions (ad libitum and abstinent) in between- or within-subjects design with counterbalanced order should enhance clarity of the role of smoking withdrawal in the relationship between smoking, stress response, and SIA. Negative findings in thermal heat pain suggest the role of pain modality in smoking and SIA (Girdler et al., 2005). Future studies should examine different pain stimuli such as ischemic pain and electrical pain stimuli, and assess whether findings from experimental studies could be generalized to chronic pain models. Whether other ingredients in cigarettes are associated with pain sensitivity should be investigated. The mediating role of psychosocial factors such as socioeconomic status (Ditre et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2010) as well as individual differences such as negative affect, ability to tolerate distress (Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, Strong, & Zvolensky, 2005), and sensitivity to anxiety (Zvolensky, Stewart, Vujanovic, Gavric, & Steeves, 2009) should be carefully assessed. Nevertheless, this study used both subjective and physiological measures, multiple pain assessments, and a systematic approach to examine the link between psychophysiological stress response, pain sensitivity, and stress-induced analgesia.

In conclusion, this study found that smokers going through their initial phase of quitting exhibited heightened pain sensitivity and a lack of stress-induced analgesia relative to nonsmokers. Smokers also showed blunted stress response as compared with nonsmokers. Reported withdrawal symptoms were related to greater pain. Dysregulations in central pain and stress regulating mechanisms during nicotine withdrawal may enhance risk for cessation failure.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants to Dr. al’Absi from the National Institute of Health (R01DA016351 and R01DA027232). We would like to thank Angie Forsberg, Elizabeth Ford, and Barbara Gay for assistance with data collection and management.

Footnotes

The authors do not have any conflict of interest regarding this manuscript.

References

- al’Absi M. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical responses to psychological stress and risk for smoking relapse. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2006;59(3):218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Buchanan T, Lovallo WR. Pain perception and cardiovascular responses in men with positive parental history for hypertension. Psychophysiology. 1996;33(6):655–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1996.tb02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Buchanan TW, Marrero A, Lovallo WR. Sex differences in pain perception and cardiovascular responses in persons with parental history for hypertension. Pain. 1999;83(2):331–338. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Hatsukami D, Davis GL. Attenuated adrenocorticotropic responses to psychological stress are associated with early smoking relapse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181(1):107–117. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Nakajima M, Grabowski J. Stress response dysregulation and stress-induced analgesia in nicotine dependent men and women. Biological Psychology. 2013;93(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Petersen KL. Blood pressure but not cortisol mediates stress effects on subsequent pain perception in healthy men and women. Pain. 2003;106(3):285–295. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Petersen KL, Wittmers LE. Blood pressure but not parental history for hypertension predicts pain perception in women. Pain. 2000;88(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Petersen KL, Wittmers LE. Adrenocortical and hemodynamic predictors of pain perception in men and women. Pain. 2002;96(1–2):197–204. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00447-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Wittmers LE, Erickson J, Hatsukami D, Crouse B. Attenuated adrenocortical and blood pressure responses to psychological stress in ad libitum and abstinent smokers. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2003;74(2):401–410. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(02)01011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KL, Pinkerton KE, Uyeminami D, Simons CT, Carstens MI, Carstens E. Antinociception induced by chronic exposure of rats to cigarette smoke. Neuroscience Letters. 2004;366(1):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL. Pharmacologic aspects of cigarette smoking and nicotine addiction. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;319(20):1318–1330. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811173192005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky MJ. Distress tolerance and early smoking lapse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(6):713–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2001;3(1):7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200124218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curvall M, Elwin CE, Kazemi-Vala E, Warholm C, Enzell CR. The pharmacokinetics of cotinine in plasma and saliva from non-smoking healthy volunteers. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1990;38:281–287. doi: 10.1007/BF00315031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre JW, Brandon TH. Pain as a motivator of smoking: effects of pain induction on smoking urge and behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(2):467–472. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre JW, Brandon TH, Zale EL, Meagher MM. Pain, nicotine, and smoking: research findings and mechanistic considerations. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137(6):1065–1093. doi: 10.1037/a0025544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fertig JB, Pomerleau OF, Sanders B. Nicotine-produced antinociception in minimally deprived smokers and ex-smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 1986;11(3):239–248. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, Gear RW. Sex differences in opioid analgesia: clinical and experimental findings. European Journal of Pain. 2004;8(5):413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim R, Maixner W. The influence of resting blood pressure and gender on pain responses. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1996;58:326–332. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France CR, Stewart KM. Parental history of hypertension and enhanced cardiovascular reactivity are associated with decreased pain ratings. Psychophysiology. 1995;52:571–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghione S. Hypertension-associated hypalgesia. Evidence in experimental animals and humans, pathophysiological mechanisms, and potential clinical consequences. Hypertension. 1996;28(3):494–504. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.28.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG, McClernon FJ, Rabinovich NE, Plath LC, Masson CL, Anderson AE, Sly KF. Mood disturbance fails to resolve across 31 days of cigarette abstinence in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):142–152. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girdler SS, Maixner W, Naftel HA, Stewart PW, Moretz RL, Light KC. Cigarette smoking, stress-induced analgesia and pain perception in men and women. Pain. 2005;114(3):372–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks PS, Ditre JW, Drobes DJ, Brandon TH. The early time course of smoking withdrawal effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;187(3):385–396. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Effects of abstinence from tobacco: valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(3):315–327. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamner LD, Girdler SS, Shapiro D, Jarvik ME. Pain inhibition, nicotine, and gender. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;6(1):96–106. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.6.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanarek RB, Carrington C. Sucrose consumption enhances the analgesic effects of cigarette smoking in male and female smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;173(1–2):57–63. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Strasburger CJ, Langkrar J. Attenuated cortisol response to psychological stress but not to CRH or ergometry in young habitual smokers. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1993;44(3):527–531. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90162-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg U, Frankenhaeuser M. Pituitary-adrenal and sympathetic-adrenal correlates of distress and effort. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1980;24(3–4):125–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(80)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. POMS Manuel-Profile of Mood Questionnaire. San Diego: Edits; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: Major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–299. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell HE, Cohen LM, al’Absi M. Physiological and psychological symptoms and predictors in early nicotine withdrawal. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2008;89(3):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousa SA, Aloyo VJ, Van Loon GR. Tolerance to tobacco smoke- and nicotine-induced analgesia in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1988;31(2):265–268. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, al’Absi M. Enhanced pain perception prior to smoking cessation is associated with early relapse. Biological Psychology. 2011;88(1):141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DE, Emont SL, Brackbill RM, Cameron LL, Peddicord J, Fiore MC. Cigarette smoking prevalence by occupation in the United States. A comparison between 1978 to 1980 and 1987 to 1990. Journal of Occupational Medicine. 1994;36(5):516–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt PD. Smoking, physiological arousal, and emotional response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1973;25(1):137–144. doi: 10.1037/h0034256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Profiles in discouragement: two studies of variability in the time course of smoking withdrawal symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(2):238–251. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF. Nicotine and the central nervous system: biobehavioral effects of cigarette smoking. The American Journal of Medicine. 1992;93(1A):2S–7S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90619-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Turk DC, Fertig JB. The effects of cigarette smoking on pain and anxiety. Addictive Behaviors. 1984;9(3):265–271. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(84)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy MP, Steptoe A, Kirschbaum C. Association between smoking status and cardiovascular and cortisol stress responsivity in healthy young men. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;1(3):264–283. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0103_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon MN, Lazar-Wesley E, Grant KA, Kunos G. Proopiomelanocortin messenger RNA is decreased in the mediobasal hypothalamus of rats made dependent on ethanol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16(6):1147–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Weingarten TN, Mantilla CB, Hooten WM, Warner DO. Smoking and pain: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(4):977–992. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ebdaf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein B. Cigarette smoking, nicotine addiction, and relaxation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1982;42(5):946–950. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.42.5.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straneva P, Hinderliter A, Wells E, Lenahan H, Girdler S. Smoking, oral contraceptives, and cardiovascular reactivity to stress. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2000;95(1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00497-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Drobes DJ. The development and initial validation of a questionnaire on smoking urges. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1467–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller D, Schalling D, Levander S, Edman G. Smoking, pain tolerance, and physiological activation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1983;79(2–3):193–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00427811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrindast MR, Khoshayand MR, Shafaghi B. The development of cross-tolerance between morphine and nicotine in mice. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;9(3):227–233. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(98)00030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Stewart SH, Vujanovic AA, Gavric D, Steeves D. Anxiety sensitivity and anxiety and depressive symptoms in the prediction of early smoking lapse and relapse during smoking cessation treatment. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(3):323–331. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]