Abstract

Hypothesis

This study evaluates the types and degree of tissue response adjacent to the electrode of multichannel cochlear implants.

Background

cochlear implant electrodes have been classified as biocompatible prostheses. Nevertheless, in some reports, electrode extrusion, chronic inflammation and even soft failure of the implant system have been attributed to a tissue response to the electrode.

Methods

All celloidin embedded temporal bones with multichannel cochlear implants from the temporal bone collection of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary were included in the study. A total of 28 temporal bones from 21 subjects were identified and processed for histology. The severity of cellular response including eosinophil and lymphocytic infiltration, giant cell reaction, new bone formation and fibrosis were scored on a scale from 0 to 3 at three 1mm-segments along the electrode: 1- first 1mm at the cochleostomy, last 1mm from the tip of electrode, and midway between these proximal and distal segments. The values were compared using the Wilcoxon test.

Results

A granulomatous reaction to the electrode was observed in 27 (96.4%) temporal bones. Eosinophil infiltration was observed in 7 (25%) temporal bones, suggesting an allergic reaction. The Inflammatory response to the electrode was significantly greater at the basal turn of cochlea close to the cochleostomy (p< 0.05) than distal to it.

Conclusion

An Inflammatory response is common after cochlear implantation and it is more robust at the cochleostomy than distal to it, suggesting the role of trauma of insertion as a contributing factor.

Keywords: tissue response, cochlear implant, giant cell, foreign body, endocochlear, Labyrinthitis

Introduction

Cochlear implants (CI) have been considered well-tolerated and biocompatible auditory prostheses with a low rate of complications that can restore the hearing of the patients with severe to profound hearing impairment (1-6). Nevertheless, there have been a number of case reports in which a pronounced inflammatory/allergic reaction to cochlear implants resulted in implant failure, extrusion, explantation and reimplantation. Puri et al. (7), Kunda et al. (8) and others (1,9-12) reported a delayed hypersensitivity or an allergic reaction to the electrode array or the receiver-stimulator unit. In addition, some reports suggested local tissue reaction as a possible explanation for cochlear implant soft failures (12,13). On the other hand, in a meta-analysis of 7132 cochlear implant recipients, 0.55 % of them (n=39) experienced extrusion of the device (1). All these studies indicated that for a number of CI users, biocompatibility of the device was an issue. Considering the incidence of the implant extrusion and pronounced inflammatory reaction to the electrode, it is reasonable to study the interaction between the electrode and its adjacent tissue within the cochlea. The histopathology of the temporal bones in cochlear implant recipients has been published previously and all reported fibrotic and neo-osteogenic reaction to cochlear implants (14-24). Nevertheless, the degree and types of inflammatory response and the locations with maximal reaction to the intracochlear portion of the electrode has not been studied systematically. In this study, using a grading system, the severity of the inflammatory response and the locations of maximal reaction were determined. The correlation between the severity of the inflammatory response and the duration of implantation, type of electrode and the tissue used for sealing the cochleostomy were also evaluated.

Methods and Materials

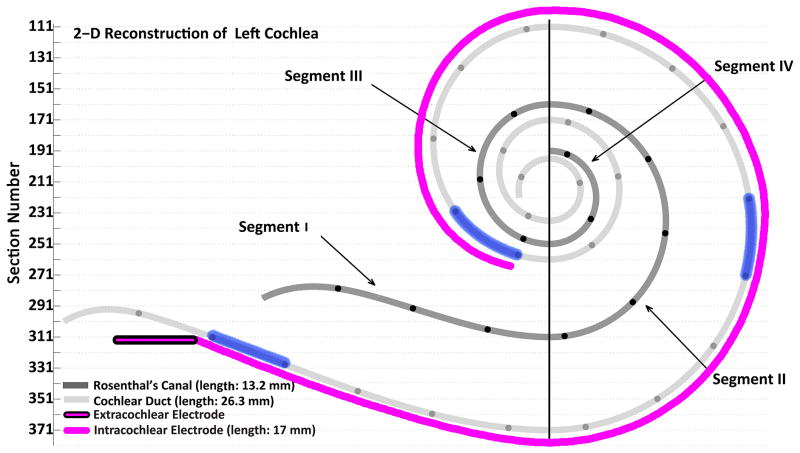

All temporal bones in the temporal bone collection of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary with multi-channel electrode embedded in celloidin were included in the study. Twenty eight temporal bones from 21 individuals (Table 1) who had undergone cochlear implantation during life were identified. The temporal bones were removed after death, fixed in 10% buffered formalin and decalcified in ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA). The electrodes were removed at this point, and then the specimens were embedded in celloidin (25). The temporal bones were sectioned at a thickness of 20 μ m in the horizontal plane, and every fifth section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin and mounted on a glass slide. Rosenthal's canal and the cochlear duct were reconstructed in two dimensions (Figure 1) by a method described by Schuknecht (26) and Otte et al. (27), and the length of Rosenthal's canal, cochlear duct, the depth and the location of electrode insertion were determined using MATLAB® software. Three 1mm-segments along the track of each electrode were selected to evaluate the degree of tissue response and cellular infiltration, namely: 1- at the cochleostomy, 2- at the tip of electrode and 3- midway along the intracochlear segment of the electrode (Figure 1). The slides associated with these three different 1mm segments were examined for fibrosis, new bone formation and lymphocyte, eosinophil and giant cell infiltration. Using a grading system, as illustrated in Figure 2, the degree of tissue response and cellular infiltration were determined for each element at these three segments by a blinded otopathologist (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 21 patients (seven patients were implanted bilaterally).

| Age/Gender | Diagnosis | Implanted ear | Device | Duration of implantation | Tissue used to seal cochleostomy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 89/F | Unknown | AS | Nucleus | 11 | Fascia |

| 2 | 73/F | Otosclerosis | AD | Nucleus | 12 | Muscle |

| 2 | 73/F | Otosclerosis | AS | Nucleus | 1 | Fascia |

| 3 | 83/M | Meniere's disease | AD | Nucleus | 12 | Fascia |

| 3 | 83/M | Meniere's disease | AS | Nucleus | 12 | Fascia |

| 4 | 89/F | Unknown | AS | Advanced Bionics | 9 | Fascia |

| 5 | 80/M | Unknown | AS | Nucleus | 6 | ? |

| 6 | 88/M | Meniere's disease | AD | Advanced Bionics | 6 | Muscle |

| 6 | 88/M | Meniere's disease | AS | Nucleus | 17 | ? |

| 7 | 78/M | Unknown | AS | Nucleus | 7 | Fascia |

| 8 | 83/M | Unknown | AD | Nucleus | 7 | Fascia |

| 9 | 71/F | Unknown | AD | Nucleus | 12 | Fascia |

| 9 | 71/F | Unknown | AS | Nucleus | 12 | Fascia |

| 10 | 70/M | Acoustic neuroma | AD | Nucleus | 11 | Fascia |

| 11 | 74/M | Unknown | AD | Nucleus | 12 | Fascia |

| 12 | 82/F | Unknown | AS | Advanced Bionics | 8 | Fat graft |

| 13 | 83/M | Otosclerosis | AS | Nucleus | 23 | Muscle |

| 14 | 82/M | Unknown | AS | Advanced Bionics | 8 | Fascia |

| 15 | 76/M | Unknown | AS | Nucleus | 18 | Fascia |

| 16 | 74/F | Otosclerosis | AS | Advanced Bionics | 8 | ? |

| 16 | 74/F | Otosclerosis | AD | Advanced Bionics | 8 | ? |

| 17 | 57/M | Superficial siderosis | AD | Nucleus | 7 | Fascia |

| 18 | 71/M | Unknown | AD | Nucleus | 13 | Muscle |

| 18 | 71/M | Unknown | AS | Nucleus | 12 | Fascia |

| 19 | 68/M | Skull fracture | AD | Nucleus | 20 | Fascia |

| 19 | 68/M | Skull fracture | AS | Nucleus | 3 | ? |

| 20 | 84/F | Unknown | AD | Nucleus | 13 | Muscle |

| 21 | 92/M | Meniere's disease | AS | Nucleus | 11 | Fascia |

AS: left, AD: right; F: female; M: male; “?”: not known.

Figure 1.

Two dimensional reconstruction of left cochlear duct, Rosenthal's canal and path of electrode array of case 5. The vertical line divides Rosenthal's canal to 4 segments. The black circles on Rosenthal's canal and on the cochlear duct are 1 mm apart. Three 1mm-segments of the cochlea (highlighted in blue) were studied to determine the extent of local tissue response toward the electrode: 1- 1mm-segment adjacent to the cochleostomy 2- 1mm-segment at the tip of electrode 3- 1mm-segment at the middle of the electrode track.

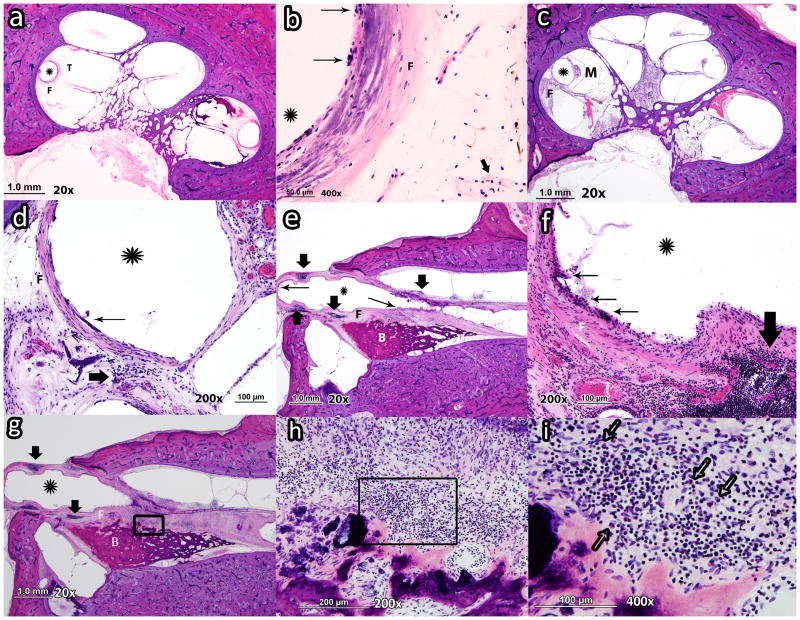

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of 3 cochleae at three locations along electrode array (tip, middle, cochleostomy). a: Asterisk shows the outline of the electrode in case# 6 (left) close to the tip of the electrode (T) with mild fibrosis (grade 1) and no new bone formation (grade 0). b: same temporal bone at higher magnification which shows mild foreign body giant cell formation (grade 1) with mild lymphocytic infiltration (grade 1). c: Asterisk shows the outline of the electrode in case# 14 close to the middle of the electrode array (M) with moderate fibrosis (F) (grade 2) and no evidence of new bone formation (grade 0). d: same cochlea at higher magnification which shows moderate foreign body giant cell formation (grade 2) and moderate lymphocytic infiltration (grade 1). e: Asterisk shows the outline of the electrode in case # 19 (left) close to the cochleostomy with severe fibrosis (grade 3) and severe new bone formation(grade 3). f: case# 19 cochlea at higher magnification which shows severe giant cell formation (grade 3) and intense lymphocytic infiltration (grade 3). g: asterisk shows the outline of the electrode in case # 19 (left) close to the cochleostomy. Lymphocytic infiltration, fibrosis and new bone formation can be recognized. h: Higher magnification of area within black box in Figure g. The lymphocytic (grade 3) and eosinophilic infiltration (grade 2) can be recognized. i: Higher magnification of area within black box in Figure h. Many eosinophils with bilobed nuclei and cytoplasm filled with large, red refractile granules can be recognized. (Thick arrow: lymphocytes; Thin arrow: foreign body giant cells; Hollow arrow: eosinophil; M: middle of the electrode; T: tip of the electrode; F: fibrosis; B: new bone formation)

Table 2.

Inflammatory cell infiltration, fibrotic reaction and new bone formation scaling at three different 1mm-segments: 1- at the cochleostomy 2- middle of the electrode 3- the tip of the electrode.

| At the cochleostomy | Middle of electrode | Tip of the electrode | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | GC | E | F | B | L | GC | E | F | B | L | GC | E | F | B | |

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 11 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 13 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 14 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 15 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 16 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 16 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 17 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 18 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 18 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 19 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 19 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 20 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 21 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

L: lymphocytic infiltration; GC: foreign body giant cell infiltration; E: eosinophil infiltration; F: fibrotic reaction; B: new bone formation. (0= none, 1= mild infiltration or presence, 2= moderate infiltration or presence, 3= severe infiltration or presence)

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the severity of tissue reaction at these three locations. The Mann-Whitney U Test was used to compare the severity of tissue reaction between different electrode types (Cochlear Nucleus® vs. Advanced Bionics®) and a similar method was used to compare the degree of inflammatory response based on the tissues used to seal the cochleostomy (fascia vs. muscle). The correlation between the duration of implantation and the severity of tissue reaction was evaluated using Spearman's rank correlation analysis.

Results

Twenty eight temporal bones from 21 profoundly hearing-impaired patients who had undergone cochlear implantation during life met inclusion criteria. There were 7 females and 14 males with an average age of 78 years ranging from 57 to 92 (Table 1). In all cases electrodes were inserted through a bony cochleostomy. There were six Advanced Bionics electrodes® (Sylmar, CA) and 22 had Cochlear Nucleus® electrodes (Cochlear Corp., Sydney Australia). The duration of implantation ranged from 1 to 23 years with an average of 11 years. All patients had uneventful implantation except cases 2 and 18. The right cochlear implant in case# 2 was explanted 12 years after implantation because of the development of cholesteatoma. In case# 18 there was soft failure bilaterally, as previously described (12). With the exception of one temporal bone (case # 27), all other 27 temporal bones had a foreign body giant cell infiltration in at least 1 segment. Case# 18 had the most severe reaction which caused a severe granulomatous reaction with necrosis (12). Lymphocytic infiltration was observed in 25 temporal bones (89.2%). In 7 temporal bones there was eosinophil infiltration (25%).

The severity of infiltration by foreign body giant cells, lymphocytes and eosinophils, new bone formation and fibrotic reaction were compared across different points of the electrode track in each temporal bone by the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test (Table 3). As shown in Table 3, the infiltration of foreign body giant cells, lymphocytes and eosinophils at the cochleostomy was significantly more severe than the cellular response at the middle of the intracochlear segment of the electrode and at the tip of the electrode. However, the difference in eosinophilic reaction between the tip of the electrode and the cochleostomy did not reach significance (p-value= 0.129). The cellular reaction at the tip and the middle of the electrode did not differ significantly (p-values> 0.05). As can be seen in the Table 3, fibrosis and new bone formation were less severe with increasing distance from the cochleostomy.

Table 3.

Wilcoxon rank test results comparing the different elements of local tissue response between different segments.

| LM - LC | LT - LC | LT - LM | GCM - GCC | GCT - GCC | GCT - GCM | EM - EC | ET - EC | ET -EM | FM -FC | FT -FC | FT - FM | BM -BC | BT -BC | BT - BM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNR | 9.82 | 9.00 | 2.50 | 9.09 | 9.06 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.25 | .00 | 9.50 | 14.00 | 7.00 | 12.50 | 13.50 | 4.50 |

| MPR | 4.00 | .00 | 2.50 | 7.50 | 8.00 | 3.00 | .00 | 2.00 | 1.50 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| Z | -3.63 | -3.73 | 0.00 | -3.50 | -3.53 | -0.45 | -2.07 | -1.52 | -1.34 | -3.87 | -4.69 | -3.50 | -4.36 | -4.52 | -2.64 |

| P-value | <0.01 | <0.01 | 1.00 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.66 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.18 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

L: lymphocyte infiltration; GC: foreign body giant cell infiltration; E: eosinophil infiltration; F: fibrotic reaction; B: new bone formation; M: middle of the electrode; C: cochleostomy; T: tip of the electrode; MNR: mean negative rank; MPR: mean positive rank.

The Mann Whitney test (Table 4) did not demonstrate a significant difference in the cellular, fibrotic and osteogenic reactions between the two types of electrode (Cochlear Nucleus ® vs. Advanced Bionics®) with the exception of the foreign body giant cell infiltration which was less pronounced at the tip of the Cochlear Nucleus® electrodes. There was no difference in inflammatory response between fascia and muscle grafts (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mann Whitney test results comparing the effect of different types of cochlear implant electrodes (Cochlear Nucleus® vs. Advanced Bionics®) as well as tissue used to seal the cochleostomy (fascia vs. muscle) on different elements of foreign body reaction near the electrode.

| LC | GCC | EC | FC | BC | LT | GCT | ET | FT | BT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRCN | 15.84 | 14.86 | 15.45 | 13.91 | 13.86 | 14.00 | 12.93 | 15.05 | 13.23 | 13.68 |

| MRAB | 9.58 | 13.17 | 11.00 | 16.67 | 16.83 | 16.33 | 20.25 | 12.50 | 19.17 | 17.50 |

| MWU D | 36.50 | 58.00 | 45.00 | 53.00 | 52.00 | 55.00 | 31.50 | 54.00 | 38.00 | 48.00 |

| Z D | -1.74 | -0.51 | -1.55 | -0.90 | -0.96 | -0.66 | -2.09 | -1.11 | -1.79 | -1.13 |

| P-value D | 0.08 | 0.61 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.51 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.26 |

| N D | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| MRF | 12.38 | 12.18 | 11.68 | 11.47 | 10.91 | 11.35 | 11.68 | 11.41 | 11.06 | 10.71 |

| MRM | 8.50 | 9.20 | 10.90 | 11.60 | 13.50 | 12.00 | 10.90 | 11.80 | 13.00 | 14.20 |

| MWU S | 27.50 | 31.00 | 39.50 | 42.00 | 32.50 | 40.00 | 39.50 | 41.00 | 35.00 | 29.00 |

| Z S | -1.27 | -1.10 | -0.30 | -0.05 | -0.92 | -0.21 | -0.25 | -0.18 | -0.67 | -1.20 |

| P-value S | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.76 | 0.96 | 0.36 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.50 | 0.23 |

| N S | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

MRCN: mean rank in Cochlear Nucleus® group; MRAB: mean rank in Advanced Bionics® group; MRF: mean rank in fascia group; MRM: mean rank in muscle group; MWU: Mann-Whitney U; L: lymphocyte infiltration; GC: foreign body giant cell infiltration; E: eosinophil infiltration; F: fibrotic reaction; B: new bone formation; C: cochleostomy; T: tip of the electrode; D: comparison based on the device used to stimulate cochleae (Cochlear Nucleus® vs. Advanced Bionics®); S: comparison based on the tissue used to seal the cochleostomy (muscle vs. fascia).

As indicated in Table 5, Spearman's correlation analysis did not demonstrate any correlation between the duration of implantation and the cellular, fibrotic and osteogenic reactions.

Table 5.

Spearman's analysis results evaluating correlation between duration of implantation and different elements of foreign body reaction.

| Duration of implantation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of correlation | P-value | N | |

| LC | .207 | .290 | 28 |

| GCC | .115 | .560 | 28 |

| EC | -.021 | .916 | 28 |

| FC | -.062 | .753 | 28 |

| BC | .030 | .881 | 28 |

| LT | .057 | .774 | 28 |

| GCT | -.277 | .153 | 28 |

| ET | .208 | .288 | 28 |

| FT | .035 | .860 | 28 |

| BT | .157 | .426 | 28 |

L: lymphocyte infiltration; GC: foreign body giant cell infiltration; E: eosinophil infiltration; F: fibrotic reaction; B: new bone formation; C: cochleostomy; T: tip of the electrode.

Discussion

Although cochlear implants have been widely accepted as biocompatible prostheses (2-6), there have been several reports describing the extrusion of implants and a severe allergic reaction to intracochlear and the receiver-stimulator segments of the electrode resulting in explantation and soft failure (1,7-9,12,13). Ina review (1), device-associated complications occurred in 311 individuals of 7132 patients. Of these 311 patients, 39 experienced device extrusion due to severe local tissue response.

It has been also suggested that the severity of local tissue response may be inversely correlated with survival of the spiral ganglion cells (19), performance after implantation, and preservation of the residual acoustic hearing (28,29). The current study was designed to examine the local tissue response and its severity caused by the intracochlear segment of the implanted electrodes at three different locations (Figure 1 and Table 2). The association between the extent of inflammatory response and different types of electrode arrays as well as the duration of implantation was also evaluated.

Cochlear implantation is always accompanied by surgical injury, which initiates an acute inflammatory response to the electrode. The acute phase of inflammation may be replaced by a chronic phase due to a foreign body reaction induced by components of the electrode array involving macrophages and their derivatives (epithelioid cells and foreign body giant cells) and lymphocytes (30-33). A macrophage is able to phagocytize particles up to 5 μm (34). If the particle size is larger, macrophages coalesce to form foreign body giant cells (35,36). The chronic inflammatory response includes granulation tissue identified by the presence of macrophages, infiltration of fibroblasts, and angiogenesis. Granulation tissue is the precursor of fibrous capsule formation, and granulation tissue is separated from the implant by the cellular components of the foreign body reaction, a one to two-cell layer of macrophages, and foreign body giant cells (30).

In contrast to the hypothesis that a foreign body reaction is rare around cochlear implant electrodes (1,5,37), in the current study foreign body giant cell infiltration and granulomatous reaction was observed in 27 of 28 temporal bones (96.4 %) which is significantly higher than the previous reports (12,24,38). In two separate studies, Nadol et al. observed foreign body granulomatous reaction in the presence of an intracochlear electrode in 75 % (n= 8) and 57 % (n= 21) of temporal bones (12,24). Migirov et al. (38) reported chronic inflammatory response with foreign body giant cells in the presence of the receiver/stimulator segment of the implant in 46.7 % of the patients (n= 15). In the present study, the foreign body giant cells appeared as linear multinucleated cells between the electrode array and the fibrous capsule (Figure 2d).

As shown in Table 3, the lymphocytic and giant cell infiltrations were significantly greater at the cochleostomy compared to the middle and the tip of the electrode. The eosinophil granulocyte infiltration (Figure 2) that was seen in 25 % of the implanted temporal bones was not reported in previous studies. The presence of eosinophils in chronic inflammation suggests type I hypersensitivity mediated by IgE and an allergic reaction to components of the electrode array in these 7 temporal bones. The eosinophilic reaction was also significantly more robust at the cochleostomy compared to the middle of the electrode. It was also more pronounced at the cochleostomy compared to the tip of the electrode but did not reach a significant level (Table 3).

In the current study similar to previous studies (12,15,17,19,38), all electrodes at the cochleostomy were surrounded by a fibrous sheath (Figure 2). The severity of the fibrotic reaction and new bone formation adjacent to the intracochlear part of the electrode was significantly more apparent at the cochleostomy compared to the middle and the tip of the electrode (Table 3), which is consistent with the result of previous studies (39,40). The local tissue reaction may alter the normal anatomy and cause malfunction of cochlear implant and poorer performance after cochlear implantation (14,19,28,29,41). Nadol reported negative correlation between the severity of new bone formation and survival of spiral ganglion cells in deafened ears (42). Deleterious effect of fibrosis and new bone formation in implanted temporal bones was reported by Fayad et al. (39) especially at the cochleostomy where the local tissue response was more robust. Seyyedi et al. (43) reported significantly fewer spiral ganglion cells in the implanted human ear as compared to the unimplanted side suggesting that insertion trauma and resultant local tissue response were contributing factors.

Our data suggests that the duration of implantation, the type of electrode and the tissue used to seal the cochleostomy do not have any correlation with the severity of cellular and stromal reactions. Similarly, Migirov et al. did not find any association between the duration of implantation and the presence of foreign body reaction (38). Nadol et al. (24) did not find correlation between the presence of foreign body reaction and duration of implantation, type of electrode and the tissue used to seal the cochleostomy.

The heightened reaction at the cochleostomy compared to more apical regions of the cochlea suggests that the trauma of insertion, violation of the normal anatomy, disruption of the intracochlear endosteum and release of inflammatory mediators may accentuate the local tissue response and foreign body reaction. Less traumatic techniques of electrode insertion such as insertion through round window membrane may decrease the severity of local tissue response (44,45).

Conclusion

The current study showed that a cellular immune response after cochlear implantation is more common than previously reported. In 25 % of temporal bones, an allergic type I reaction may be involved. A heightened cellular immune response at the cochleostomy suggests that trauma of insertion may be a contributing factor.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01-DC000152 from the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

References

- 1.Benatti A, Castiglione A, Trevisi P, et al. Endocochlear inflammation in cochlear implant users: case report and literature review. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2013;77:885–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding X, Tian H, Wang W, et al. Cochlear implantation in China: review of 1,237 cases with an emphasis on complications. ORL; journal for oto-rhino-laryngology and its related specialties. 2009;71:192–5. doi: 10.1159/000229297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray J, Gibson W, Sanli H. Surgical complications of 844 consecutive cochlear implantations and observations on large versus small incisions. Cochlear implants international. 2004;5:87–95. doi: 10.1179/cim.2004.5.3.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venail F, Sicard M, Piron JP, et al. Reliability and complications of 500 consecutive cochlear implantations. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2008;134:1276–81. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2008.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Issa TK, Bahgat MA, Linthicum FH., Jr Tissue reaction to prosthetic materials in human temporal bones. Am J Otol. 1983;5:40–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webb RL, Clark GM, Shepherd RK, et al. The biologic safety of the Cochlear Corporation multiple-electrode intracochlear implant. Am J Otol. 1988;9:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puri S, Dornhoffer JL, North PE. Contact dermatitis to silicone after cochlear implantation. The Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1760–2. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000172202.58968.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunda LD, Stidham KR, Inserra MM, et al. Silicone allergy: A new cause for cochlear implant extrusion and its management. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neu. 2006;27:1078–82. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000235378.64654.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertuleit H, Groden C, Schafer HJ, et al. Removal of a cochlea implant with chronic granulation labyrinthitis and foreign body reaction. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 1999;78:304–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-996876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim HJ, Lee ES, Park HY, et al. Foreign body reaction after cochlear implantation. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2011;75:1455–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho EC, Dunn C, Proops D, et al. Case report: explantation of a cochlear implant secondary to chronic granulating labyrinthitis. Cochlear implants international. 2003;4:191–5. doi: 10.1179/cim.2003.4.4.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadol JB, Jr, Eddington DK, Burgess BJ. Foreign body or hypersensitivity granuloma of the inner ear after cochlear implantation: one possible cause of a soft failure? Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neu. 2008;29:1076–84. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31818c33cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neilan RE, Pawlowski K, Isaacson B, et al. Cochlear implant device failure secondary to cholesterol granuloma-mediated cochlear erosion. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neu. 2012;33:733–5. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182544fff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark GM, Shute SA, Shepherd RK, et al. Cochlear implantation: osteoneogenesis, electrode-tissue impedance, and residual hearing. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1995;166:40–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fayad J, Linthicum FH, Jr, Otto SR, et al. Cochlear implants: histopathologic findings related to performance in 16 human temporal bones. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:807–11. doi: 10.1177/000348949110001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis DM. Histopathology associated with cochlear implants. Ear Nose Throat J. 1987;66:86–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linthicum FH, Jr, Fayad J, Otto SR, et al. Cochlear implant histopathology. Am J Otol. 1991;12:245–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marsh MA, Jenkins HA, Coker NJ. Histopathology of the temporal bone following multichannel cochlear implantation. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 1992;118:1257–65. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880110125022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadol JB, Jr, Shiao JY, Burgess BJ, et al. Histopathology of cochlear implants in humans. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:883–91. doi: 10.1177/000348940111000914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Leary MJ, Fayad J, House WF, et al. Electrode insertion trauma in cochlear implantation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:695–9. doi: 10.1177/000348949110000901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shepherd RK, Matsushima J, Martin RL, et al. Cochlear pathology following chronic electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve: II. Deafened kittens. Hear Res. 1994;81:150–66. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutton D, Miller J. Intracochlear implants: potential histopathology. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 1983;16:227–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zappia JJ, Niparko JK, Oviatt DL, et al. Evaluation of the temporal bones of a multichannel cochlear implant patient. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:914–21. doi: 10.1177/000348949110001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nadol JB, Jr, Eddington DK. Histologic evaluation of the tissue seal and biologic response around cochlear implant electrodes in the human. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neu. 2004;25:257–62. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuknecht H. Temporal bone removal at autopsy. Preparation and uses. Arch Otolaryngol. 1968;87:129–37. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1968.00760060131007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuknecht HF. Techniques for study of cochlear function and pathology in experimental animals; development of the anatomical frequency scale for the cat. AMA Arch Otolaryngol. 1953;58:377–97. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1953.00710040399001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otte J, Schunknecht HF, Kerr AG. Ganglion cell populations in normal and pathological human cochleae. Implications for cochlear implantation. The Laryngoscope. 1978;88:1231–46. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi CH, Oghalai JS. Predicting the effect of post-implant cochlear fibrosis on residual hearing. Hear Res. 2005;205:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Leary SJ, Monksfield P, Kel G, et al. Relations between cochlear histopathology and hearing loss in experimental cochlear implantation. Hear Res. 2013;298:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Seminars in immunology. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franz S, Rammelt S, Scharnweber D, et al. Immune responses to implants - a review of the implications for the design of immunomodulatory biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6692–709. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, et al. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2010. pp. 70–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin R, Strayer DS, Rubin E. Rubin's Pathology: Clinicopathologic Foundations of Medicine. Philadlphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. p. 1464. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xia Z, Triffitt JT. A review on macrophage responses to biomaterials. Biomed Mater. 2006;1:R1–9. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/1/1/R01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeFife KM, Jenney CR, McNally AK, et al. Interleukin-13 induces human monocyte/macrophage fusion and macrophage mannose receptor expression. J Immunol. 1997;158:3385–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNally AK, Anderson JM. Interleukin-4 induces foreign body giant cells from human monocytes/macrophages. Differential lymphokine regulation of macrophage fusion leads to morphological variants of multinucleated giant cells. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1487–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linthicum FH, Jr, Fayad J, Otto S, et al. Inner ear morphologic changes resulting from cochlear implantation. Am J Otol. 1991;12(Suppl):8–10. discussion 8-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Migirov L, Kronenberg J, Volkov A. Local tissue response to cochlear implant device housings. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neu. 2011;32:55–7. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182009d5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fayad JN, Makarem AO, Linthicum FH., Jr Histopathologic assessment of fibrosis and new bone formation in implanted human temporal bones using 3D reconstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li PM, Somdas MA, Eddington DK, et al. Analysis of intracochlear new bone and fibrous tissue formation in human subjects with cochlear implants. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116:731–8. doi: 10.1177/000348940711601004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu J, Shepherd RK, Millard RE, et al. Chronic electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve at high stimulus rates: a physiological and histopathological study. Hear Res. 1997;105:1–29. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)00193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nadol JB., Jr Patterns of neural degeneration in the human cochlea and auditory nerve: implications for cochlear implantation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:220–8. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(97)70178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seyyedi M, Eddington DK, Nadol JB., Jr Effect of monopolar and bipolar electric stimulation on survival and size of human spiral ganglion cells as studied by postmortem histopathology. Hear Res. 2013;302:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burghard A, Lenarz T, Kral A, et al. Insertion site and sealing technique affect residual hearing and tissue formation after cochlear implantation. Hear Res. 2014;312C:21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richard C, Fayad JN, Doherty J, et al. Round window versus cochleostomy technique in cochlear implantation: histologic findings. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neu. 2012;33:1181–7. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318263d56d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]