Abstract

Microbes have long been adapted for the biosynthetic production of useful compounds. There is increasing demand for the rapid and cheap microbial production of diverse molecules in an industrial setting. Microbes can now be designed and engineered for a particular biosynthetic purpose, thanks to recent developments in genome sequencing, metabolic engineering, and synthetic biology. Advanced tools exist for the genetic manipulation of microbes to create novel metabolic circuits, making new products accessible. Metabolic processes can be optimized to increase yield and balance pathway flux. Progress is being made towards the design and creation of fully synthetic microbes for biosynthetic purposes. Together, these emerging technologies will facilitate the production of designer microbes for biosynthesis.

Introduction

Imagine a world where microbes produce the electricity that lights our homes and schools, the fuel that runs our cars, the pharmaceuticals that keep us healthy, and the foodstuffs that we eat. While such ideas may sound far-fetched, many of these applications are already in existence, or are within our reach [1-4]. Microbes are a useful platform for the biosynthesis of desirable products, evidenced by their long history of adaption for the food and pharmaceutical industries. Microbes grow quickly on relatively cheap carbon sources, culture size can easily be increased to scale up production, and the naturally occurring metabolic processes of microbes can be harnessed to produce significant quantities of useful compounds [5]. It is therefore unsurprising that both microbial primary metabolites (eg. vitamins, nucleotides, ethanol and organic acids) and secondary metabolites (eg. antibiotics, cholesterol lowering compounds and anti-tumor compounds) have a global market value of several billion dollars [6].

Yet, microbial industrial biotechnology has not been without its drawbacks. Traditionally, the yields and repertoire of products were limited to the natural capacity of the existing microbial biosynthetic pathways. This problem has partially been addressed by exploring microbial diversity to find other species that have evolved to become more efficient at producing a particular target compound, or different compounds [7]. However, laboratory conditions for the cultivation of the newly discovered microbes often require extensive optimization, and the characterization of the biosynthetic pathways responsible for producing the metabolites of interest is a time-consuming process. Therefore, these measures have only provided a temporary stopgap solution to the challenge of being able to fully manipulate the biosynthetic output of a broad range of desirable and valuable products on demand.

With the dawn of the post-genomics era came a revolutionary change in the way that we understand and view microbial biosynthetic pathways [8]. An exceptionally large amount of microbial genome information is available via databases such as NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/MICROBES/microbial_taxtree.html), GenomeNet (http://www.genome.jp/), and JGI (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/). Together with our biochemical knowledge of enzyme function, and our ability to synthesize DNA from scratch, we have a powerful toolset for the discovery and design of new biosynthetic networks [9]. The last decade has seen incredible advances in our ability to tailor microbial enzymes and metabolic processes for our purposes, thanks to developments in the fields of metabolic engineering, enzyme evolution, and synthetic biology [10-12]. Now, we can program microbial factories by combining diverse enzymes in a heterologous host to produce compounds that were previously unattainable [13]. Novel and preexisting metabolic pathways can be optimized by mediating strict control over the expression of the encoded pathway enzymes, as well as by engineering the enzymes to improve efficiency [14]. We even have the capability to create beyond that which is provided by nature with the advent of techniques such as de novo engineering of enzymes to carry out unnatural reactions [15], and the construction of bacterial cells with minimal and synthetic genomes [16].

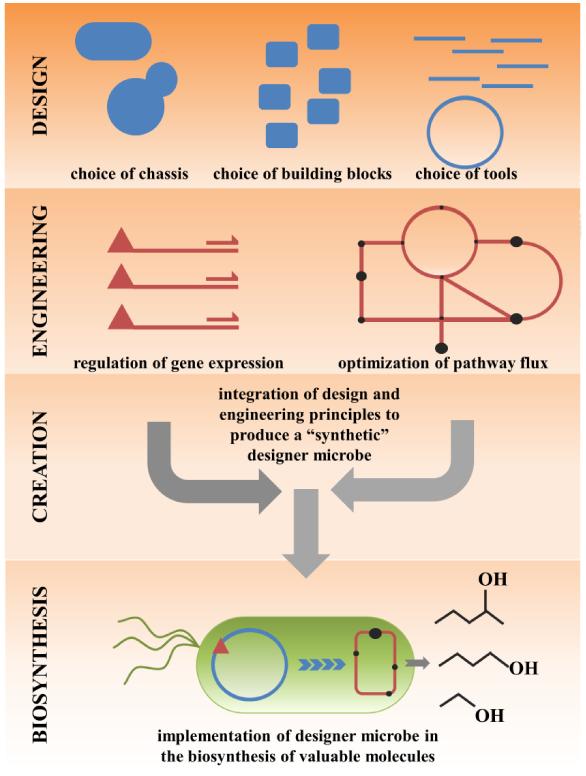

In this opinion we discuss the process of designing and engineering a microbial system for the biosynthesis of desirable compounds (Figure 1). Some of the most recent tools and technical advances are presented, and a few key examples are used to highlight successes and important design principles to take into consideration (Table 1). While not an exhaustive review, this paper will serve as a general “roadmap” to introduce readers to some of the most up-to-date trends in the production of designer microbes for biosynthesis.

Figure 1. A schematic representation of the design and engineering of a microbe for biosynthesis.

The design of a microbe for a particular biosynthetic purpose involves selection of appropriate chassis, building blocks, and DNA assembly tools. The designed microbe can then be engineered with these components. Optimization of the biosynthetic system occurs by regulation of gene expression, and metabolic flux improvement via network modeling, spatial organization and protein design. The integration of these principles and improvements can result in a tailor designed biosynthetic scheme for the high level production of valuable compounds.

Table 1. A selection of designer microbes engineered for the production of valuable compounds.

| Product of interest |

Host strain |

Design strategy | Bottlenecks and optimizations |

Highest reported yield |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saponins | S. cerevisiae |

Heterologous combinatorial pathway with a novel P450 in combination with oxidosqualene cyclase and cytochrome P450 reductase leads to hydroxylation of triterpenes at a unique position |

Coexpression with glucosyltransferase/addition of cyclodextrin leads to modification of toxic saponin product, resulting in its excretion from the cell |

5 mg−1L−1 | [61] |

| Mannitol |

Synechoc occus sp. PCC 7002 |

Heterologous pathway for mannitol production in a mutant strain inhibited in glycogen biosynthesis |

Genetic instability and low growth rate. Solutions are discussed as future improvements, including expression of mannitol transporter to remove potentially toxic mannitol from the cell |

1.1 g−1 L−1 | [62] |

| S-reticuline | E. coli | Heterologous combinatorial pathway for alkaloid production in a L-tyrosine overexpressing strain |

Designed system is optimized for bacterial expression and avoids the use of plant cytochrome P450 |

46 mg−1 L−1 | [63] |

| Short chain alkanes |

E. coli | Heterologous combinatorial pathway for enhanced fatty acid biosynthesis in mutant strains inhibited in β- oxidation |

Aldehyde decarbonylase is the rate limiting enzyme, activity was improved by growth at 30 °C due to improved protein expression |

580.8 m1−1 L−1 |

[64] |

| Shikimic acid | E. coli | Promoter swapping and chromosomal integration of carbon storage regulators leads to stable overexpression of shikimic acid pathway |

Chemically induced chromosomal evolution led to increased gene copy number and improved yields. Integration and overexpression of essential cofactor-producing enzymes further improved yields. |

3.12 g−1 L−1 | [65] |

Designing a microbe for biosynthesis

Choice of chassis

The choice of chassis, or microbial host, for biosynthetic production is dependent on the tractability of the organism. It is usual to select a microbe that can be easily cultured, that has a known genome sequence, that is amenable to genetic manipulation, and that has well understood metabolic pathways. The model organisms E. coli and S. cerevisiae meet these criteria, and are suitable for a variety of reprogramming strategies to improve product yield [17, 18].

One recent example of increasing yield from a microbial host is the manipulation of the carbon storage regulator system (Csr) of E. coli. Expression levels of the central carbon metabolism regulatory element CsrB, which binds to and disrupts the translation inhibitor protein CsrA, were altered such that E. coli cells accumulated glycolytic and TCA cycle intermediates, and used carbon more efficiently. Consequently, yields from the native fatty acid pathway of E. coli cells overexpressing CsrB increased almost two-fold relative to control cells. Furthermore, using CsrB overexpressing E. coli as a host for engineered pathways to produce biofuels led to increased yields of n-butanol (88 %) and amorphadiene (55 %) in comparison to control cells [19].

In another impressive example of improved yields, the full biosynthetic pathway for high level production of the anti-malarial drug precursor artemisinic acid was demonstrated in S. cerevisiae. The previously described amorphadiene producing strain Y337 [20] was engineered to use a copper regulated CTR3 promoter to restrict ERG9 squalene synthase expression, leading to efficient FPP utilization for amorphadiene production. This strain was then used to coexpress a cytochrome P450 CYP71AV1 and its reductase CPR1, a cytochrome b5 CYB5, an aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH1, and an alcohol dehydrogenase ADH1. This resulted in conversion of amorphadiene to artemisinic acid, with a yield of 25 g l−1 [21], the highest reported to date. This example highlights the fact that it is possible to manipulate typical laboratory microbial strains to produce industrially relevant quantities of valuable molecules, although these efforts can be labor- and funding-intensive.

Choice of building blocks

The building blocks, or enzymes that constitute the metabolic pathway to be expressed in a microbial host, can be obtained from diverse sources. The extensive sequence databases that are available facilitate a phylogenetic approach to discover paralogous genes encoding enzymes with the same function [22]. Biochemical data demonstrates that some of these enzymes have evolved to become more efficient and/or robust, and that evolution has served to diversify the catalytic range of enzymes [23]. We can make use of this diversity to engineer biosynthetic schemes with the most suitable building blocks for a particular purpose. Further, by applying a modular approach, it is possible to “mix and match” enzymes from different biosynthetic backgrounds to rewire nature and create new, tailor designed metabolic pathways for the production of a broad set of compounds [24].

Recently, Tseng and Prather engineered a novel biosynthetic pathway in E. coli to make the second generation biofuel pentanol. By taking a multi-level modular approach, they constructed a streamlined cofactor optimized route to the production of the precursors propionyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA. This precursor supply module was coupled with a second pathway to create the intermediate five carbon molecule 3-hydroxyvalerate, which can also be used as a biopolymer. Finally, a third module was included in the pathway which resulted in conversion of glucose or glycerol to pentanol, with reported yields of 116 mg/L, as well as 78 mg/L of propionate and 57 mg/L of trans-2-pentenoate [25]. While these yields are not yet on an industrial scale, this work is an elegant example of how a carefully designed metabolic engineering strategy can allow us to bypass pathway bottlenecks. It also shows that it is possible, with a degree of optimization, to combine enzymes from diverse microbial sources (in this case building blocks from 13 different microbial strains were used) in a single heterologous host. In doing so, the authors have created a non-native pathway for the biosynthesis of a diverse set of compounds of choice.

Choice of tools

There are a multitude of tools, or DNA synthesis technologies, available for the genetic manipulation of our chosen chassis. Techniques such as DNA assembler [26] and Gibson assembly [16] have facilitated the rapid integration of large pieces of DNA in a heterologous host (Table 2). The genome sequence of the heterologous host can also be altered using high-throughput evolution techniques like multiplex genome engineering and accelerated evolution (MAGE) [27]. Furthermore, the emerging field of genome editing takes advantage of the natural DNA repair mechanisms of cells following nuclease-mediated double-strand breaks, thereby allowing site-specific engineering of cellular genomic DNA. Current genome editing techniques rely upon zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) [28], TALE nucleases (TALENs) [29], and very recently, the more efficient RNA-linked CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease system [30, 31]. The successful development of these cloning technologies is essential as they are the key link between a designed, theoretical system and a functional programmed biosynthetic pathway in an engineered microbial host.

Table 2. A selection of tools for DNA assembly for the design of a microbial chassis.

| Method of assembly |

Features | Advantages | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Small DNA

assembly |

||||

|

| ||||

| BglBricks | Restriction and ligation |

A variation of the standardized BioBrick system allowing scarless cloning |

Useful for creating protein fusions with varying expression profiles |

[66] |

| CPEC | PCR | A simplified version of sequence independent cloning requiring only DNA polymerase |

A quick and efficient method that can be carried out in one pot with a single enzyme |

[67] |

| Golden GATEway | Restriction and ligation, recombination |

Couples Golden Gate and Multisite GatewayTM cloning techniques |

A modularized approach to create fusion proteins and complex DNA assemblies |

[68, 69] |

|

| ||||

|

Larger DNA

assembly |

||||

|

| ||||

| SLIC | Homologous recombination |

Uses homologous recombination and single-strand annealing to assemble multiple DNA fragments |

No requirement for sequence specific sites, up to 10 fragments can be assembled at once |

[70] |

| DNA Assembler | Homologous recombination |

Relies on homologous recombination in yeast to create DNA assemblies either on a plasmid or on a chromosome |

Only PCR is required to prepare DNA, followed by a one- step yeast transformation |

[26] |

|

| ||||

|

Genome scale

assembly |

||||

|

| ||||

| Bacillus GenoMe vector |

Domino cloning, homologous recombination |

Overlapping DNA sequences are assembled by homologous recombination in B. subtilis |

No need to purify DNA fragments, size of final assembly can be scaled up |

[71] |

| Cotransformation | Cotransformation and homologous recombination |

Overlapping DNA fragments are transformed into yeast and assembled by homologous recombination |

Enables assembly of entire bacterial genomes which are stably maintained in yeast |

[72] |

The recently described “clonetegration” method offers an alternative to traditional plasmid-based expression of genes in bacterial cells. Here, the authors created a hybrid vector (One-Step Integration Plasmid, pOSIP) that contains a cloning module, a heat-inducible integrase-containing integration module, and the attP site necessary for site-specific recombination at the attB site on the bacterial chromosome. They showed that cloning and integration (clonetegration) can be conducted simultaneously, providing a simple and quick method to integrate multiple expression cassettes at separate loci on a bacterial chromosome [32]. Streamlined technologies such as this method and other site-specific recombination methods [33, 34] hold great potential for synthetic biology and for the rapid assembly of new biosynthetic pathways in an engineered microbe.

Engineering a microbe for biosynthesis

Regulation of gene expression

Regulation of gene expression is one of the key control elements for any engineered microbial biosynthetic pathway, and is necessary to ensure sufficient expression of enzymes, to prevent placing excessive metabolic burden on the host, and to optimize pathway flux. Control is mediated by promoters, which can either act as “on/off” switches, or as “dimmer” switches, allowing varying degrees of gene expression. Predicting and modelling the strength of promoters and their regulatory elements [35, 36] offers an in silico approach to precisely tune a novel metabolic circuit. Creation of promoter libraries introduces a level of diversity that can offset the challenge of selecting multiple promoters with different strengths that are suitable for optimized expression of a biosynthetic pathway [37].

A strong synthetic hybrid promoter was recently created and characterized for the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Combining tandem repeats of a shortened 257 base pair upstream activating sequence (UAS) of the TEF promoter with a full length TEF promoter yielded a new hybrid promoter UASTEF. Further linking of this promoter with tandem repeats of truncated versions of UAS (lacking 27 base pairs from its 3′ end), and a separate upstream activating sequence, resulted in a 3.5 fold higher level of expression of GFP and β-galactosidase than the native promoter [38, 39]. This study underlines the importance of using well-characterized regulatory elements in the construction of minimal, modular promoter parts that can be combined to increase transcriptional output.

Optimization of pathway flux

A commonly encountered hurdle to the successful engineering of a microbial biosynthetic pathway is optimization of metabolic flux for maximum yields. Bottlenecks can be caused by insufficient precursor supply, suboptimal enzyme activity or diffuse intracellular spacing of pathway enzymes. A host of tools and techniques are now available to circumvent these problems, including metabolic flux analysis, network visualization, protein modelling and design, and spatial organization of pathways [40-43].

One method to improve metabolic flux is “multivariate-modular pathway engineering approach”, which was used to optimize production of anticancer taxol precursors in E. coli. By separating the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway into two modules – a native upstream precursor supply module, and a heterologous downstream isoprenoid producing module – optimal pathway balance was achieved. Four of the eight native genes required for the production of the C5 precursor molecules DMAPP and IPP were cloned together in an operon and were placed under an inducible promoter, resulting in increased yields from the native MEP pathway. Excess precursors were channelled into the second module, which included the heterologously expressed GGPP synthase and taxadiene synthase. Optimized growth conditions in fed-batch cultivations resulted in production of 1020 mg/L of taxadiene [44].

In another example, fatty acid production in E. coli was boosted by regulating transcription of a modularized biosynthetic pathway. Overexpression of acetyl-CoA carboxylase to improve levels of the precursor malonyl-CoA, and concomitant knockout of the competing fatty acyl-CoA synthetase pathway resulted in three fold increase in fatty acid production. Yields were further improved by tightly regulating expression of codon-optimized plant derived genes for production of fatty acids. This promoter-driven modularization of the pathway and transcriptional fine tuning resulted in a 46 % gain in fatty acid production (2.04 g/L) in comparison to native E. coli cells [45]. This case shows that engineering strategies may be used in an integrative approach to achieve design goals.

Creating a synthetic microbe

The ideal scenario would be creating a perfect microbial factory from scratch, without the need to alter or optimize already existing systems. Progress towards this goal has already been made with the development of Mycoplasma mycoides, the first microbe with a chemically synthesized genome [16]. Several years of intensive research were necessary to produce this microbe [46], during which time the advanced techniques of genome transplantation [47] and genome assembly [48] were created, and have since been applied in the engineering of other systems [49]. Furthermore, efforts to model the minimal genome requirement of a microbe have been ongoing for several years, and could lead to the development of highly efficient minimized cell factories for a given purpose [50-52]. Attempts have also been made to create abstract cell-free systems, using fatty acid and liposome assemblies to house the minimal components of life, again streamlining production pathways [53, 54]. While these advancements hold great promise for microbial biotechnology, we currently have a limited understanding of necessary cellular metabolic networks, and face many challenges in the creation of truly synthetic microbes [55].

Conclusions and outlooks

Recent developments in genome sequencing and our ability to manipulate large pieces of DNA have contributed to the successful implementation of metabolic engineering and synthetic biology design principles in creating microbes for biosynthesis. However, progress is limited by the fact that we do not have a fully streamlined procedure to design and engineer a microbe. As such, many of the efforts described here will have required excessive amounts of time, effort, and money, because we are still working on a “trial and error” basis. The development of computer-aided design (CAD) tools is necessary for the strategic and logic design of biosynthetic pathways. These types of tools would enable researchers to predict and simulate the effects of altering levels of gene expression on metabolism, to design idealized biocatalysts for the production of target molecules, and to circumvent pathway bottlenecks in silico [56-58]. Improving the design process would make engineering a microbe much more efficient and industrially relevant. Programs are currently being developed to aid metabolic pathway design [59, 60], and this emerging field has real potential to advance the production of designer microbes for biosynthesis.

Highlights.

Microbes are widely used for the biosynthesis of valuable compounds

Synthetic biology enables us to tailor design biosynthetic processes

Emerging technologies and techniques streamline the creation of designer microbes

Computational tools will make design of microbes for biosynthesis more efficient

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support by the National Institute of Health (grant GM080299, to CSD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

* Of special interest

** Of outstanding interest

- 1.Lovley DR. Electromicrobiology. Annual Review of Microbiology, Vol 66. 2012;66:391–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lan EI, Liao JC. Microbial synthesis of n-butanol, isobutanol, and other higher alcohols from diverse resources. Bioresour Technol. 2013;135:339–49. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.09.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giddings LA, Newman DJ. Microbial natural products: molecular blueprints for antitumor drugs. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;40(11):1181–210. doi: 10.1007/s10295-013-1331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smid EJ, Hugenholtz J. Functional genomics for food fermentation processes. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2010;1:497–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.food.102308.124143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchholz K, Collins J. The roots--a short history of industrial microbiology and biotechnology. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(9):3747–62. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4768-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh BK. Exploring microbial diversity for biotechnology: the way forward. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28(3):111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thornburg CC, Zabriskie TM, McPhail KL. Deep-sea hydrothermal vents: potential hot spots for natural products discovery? J Nat Prod. 2010;73(3):489–99. doi: 10.1021/np900662k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross H. Genomic mining--a concept for the discovery of new bioactive natural products. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12(2):207–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sagt CM. Systems metabolic engineering in an industrial setting. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(6):2319–26. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4738-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10**.Bar-Even A, Salah Tawfik D. Engineering specialized metabolic pathways--is there a room for enzyme improvements? Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24(2):310–9. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.10.006. An excellent review highlighting the importance of improving catalytic efficiency and specificity of enzymes for optimization of engineered metabolic pathways.

- 11.Bornscheuer UT, Huisman GW, Kazlauskas RJ, Lutz S, Moore JC, Robins K. Engineering the third wave of biocatalysis. Nature. 2012;485(7397):185–94. doi: 10.1038/nature11117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang YH, Wei KY, Smolke CD. Synthetic biology: advancing the design of diverse genetic systems. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2013;4:69–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061312-103351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JW, Na D, Park JM, Lee J, Choi S, Lee SY. Systems metabolic engineering of microorganisms for natural and non-natural chemicals. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8(6):536–46. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyle PM, Silver PA. Parts plus pipes: synthetic biology approaches to metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 2012;14(3):223–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golynskiy MV, Seelig B. De novo enzymes: from computational design to mRNA display. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28(7):340–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16**.Gibson DG, Glass JI, Lartigue C, Noskov VN, Chuang RY, Algire MA, Benders GA, Montague MG, Ma L, Moodie MM, et al. Creation of a bacterial cell controlled by a chemically synthesized genome. Science. 2010;329(5987):52–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1190719. The first report of a microbe with a fully synthesized genome, which was created using genome assembly and transplantation techniques.

- 17.Koopman F, Beekwilder J, Crimi B, van Houwelingen A, Hall RD, Bosch D, van Maris AJ, Pronk JT, Daran JM. De novo production of the flavonoid naringenin in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:155. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umenhoffer K, Feher T, Baliko G, Ayaydin F, Posfai J, Blattner FR, Posfai G. Reduced evolvability of Escherichia coli MDS42, an IS-less cellular chassis for molecular and synthetic biology applications. Microb Cell Fact. 2010;9:38. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKee AE, Rutherford BJ, Chivian DC, Baidoo EK, Juminaga D, Kuo D, Benke PI, Dietrich JA, Ma SM, Arkin AP, et al. Manipulation of the carbon storage regulator system for metabolite remodeling and biofuel production in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:79. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westfall PJ, Pitera DJ, Lenihan JR, Eng D, Woolard FX, Regentin R, Horning T, Tsuruta H, Melis DJ, Owens A, et al. Production of amorphadiene in yeast, and its conversion to dihydroartemisinic acid, precursor to the antimalarial agent artemisinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(3):E111–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110740109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21**.Paddon CJ, Westfall PJ, Pitera DJ, Benjamin K, Fisher K, McPhee D, Leavell MD, Tai A, Main A, Eng D, et al. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature. 2013;496(7446):528–32. doi: 10.1038/nature12051. An impressive report of an engineered metabolic pathway to convert amorphadiene to artemisinic acid, coupled with a synthetic route to the anit-malarial drug artemisinin.

- 22.Bergmann S, Schumann J, Scherlach K, Lange C, Brakhage AA, Hertweck C. Genomics-driven discovery of PKS-NRPS hybrid metabolites from Aspergillus nidulans. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(4):213–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiemann P, Guo CJ, Palmer JM, Sekonyela R, Wang CC, Keller NP. Prototype of an intertwined secondary-metabolite supercluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(42):17065–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313258110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J, Liu P, Fan Y, Bao H, Du G, Zhou J, Chen J. Multivariate modular metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli to produce resveratrol from l-tyrosine. J Biotechnol. 2013;167(4):404–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Tseng HC, Prather KL. Controlled biosynthesis of odd-chain fuels and chemicals via engineered modular metabolic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(44):17925–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209002109. An example of how metabolic bottlenecks can be bypassed using a simple, cofactor optimized single enzyme precursor shunt.

- 26.Shao Z, Zhao H, Zhao H. DNA assembler, an in vivo genetic method for rapid construction of biochemical pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(2):e16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang HH, Isaacs FJ, Carr PA, Sun ZZ, Xu G, Forest CR, Church GM. Programming cells by multiplex genome engineering and accelerated evolution. Nature. 2009;460(7257):894–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyon Y, Choi VM, Xia DF, Vo TD, Gregory PD, Holmes MC. Transient cold shock enhances zinc-finger nuclease-mediated gene disruption. Nat Methods. 2010;7(6):459–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reyon D, Tsai SQ, Khayter C, Foden JA, Sander JD, Joung JK. FLASH assembly of TALENs for high-throughput genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(5):460–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339(6121):819–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31**.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(11):2281–308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. An excellent description of the CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease system, with detailed protocols for the design, experimental procedures, and troubleshooting of genome engineering.

- 32.St-Pierre F, Cui L, Priest DG, Endy D, Dodd IB, Shearwin KE. One-step cloning and chromosomal integration of DNA. ACS Synth Biol. 2013;2(9):537–41. doi: 10.1021/sb400021j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colloms SD, Merrick CA, Olorunniji FJ, Stark WM, Smith MC, Osbourn A, Keasling JD, Rosser SJ. Rapid metabolic pathway assembly and modification using serine integrase site-specific recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonnet J, Subsoontorn P, Endy D. Rewritable digital data storage in live cells via engineered control of recombination directionality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(23):8884–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202344109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhodius VA, Mutalik VK, Gross CA. Predicting the strength of UP-elements and full-length E. coli sigmaE promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(7):2907–24. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salis HM, Mirsky EA, Voigt CA. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(10):946–50. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blount BA, Weenink T, Vasylechko S, Ellis T. Rational diversification of a promoter providing fine-tuned expression and orthogonal regulation for synthetic biology. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blazeck J, Liu L, Redden H, Alper H. Tuning gene expression in Yarrowia lipolytica by a hybrid promoter approach. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(22):7905–14. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05763-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blazeck J, Reed B, Garg R, Gerstner R, Pan A, Agarwala V, Alper HS. Generalizing a hybrid synthetic promoter approach in Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(7):3037–52. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40*.Delebecque CJ, Lindner AB, Silver PA, Aldaye FA. Organization of intracellular reactions with rationally designed RNA assemblies. Science. 2011;333(6041):470–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1206938. The authors use an in vivo RNA scaffold system to control protein:protein interactions between a ferredoxin and hydrogenase, resulting in a 24-fold increase hydrogen production in E. coli cells.

- 41.Mills JH, Khare SD, Bolduc JM, Forouhar F, Mulligan VK, Lew S, Seetharaman J, Tong L, Stoddard BL, Baker D. Computational design of an unnatural amino acid dependent metalloprotein with atomic level accuracy. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(36):13393–9. doi: 10.1021/ja403503m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poblete-Castro I, Binger D, Rodrigues A, Becker J, Martins Dos Santos VA, Wittmann C. In silico-driven metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida for enhanced production of poly hydroxyalkanoates. Metab Eng. 2013;15:113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Q, Tang B, Song L, Ren B, Liang Q, Xie F, Zhuo Y, Liu X, Zhang L. 3DScapeCS: application of three dimensional, parallel, dynamic network visualization in Cytoscape. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14(1):322. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ajikumar PK, Xiao WH, Tyo KE, Wang Y, Simeon F, Leonard E, Mucha O, Phon TH, Pfeifer B, Stephanopoulos G. Isoprenoid pathway optimization for Taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science. 2010;330(6000):70–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1191652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu P, Gu Q, Wang W, Wong L, Bower AG, Collins CH, Koffas MA. Modular optimization of multi-gene pathways for fatty acids production in E. coli. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1409. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glass JI. Synthetic genomics and the construction of a synthetic bacterial cell. Perspect Biol Med. 2012;55(4):473–89. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2012.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lartigue C, Glass JI, Alperovich N, Pieper R, Parmar PP, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Smith HO, Venter JC. Genome transplantation in bacteria: changing one species to another. Science. 2007;317(5838):632–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1144622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6(5):343–5. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noskov VN, Karas BJ, Young L, Chuang RY, Gibson DG, Lin YC, Stam J, Yonemoto IT, Suzuki Y, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, et al. Assembly of large, high G+C bacterial DNA fragments in yeast. ACS Synth Biol. 2012;1(7):267–73. doi: 10.1021/sb3000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gil R, Silva FJ, Pereto J, Moya A. Determination of the core of a minimal bacterial gene set. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68(3):518–37. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.518-537.2004. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shuler ML. Modeling life. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40(7):1399–407. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0567-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hashimoto M, Ichimura T, Mizoguchi H, Tanaka K, Fujimitsu K, Keyamura K, Ote T, Yamakawa T, Yamazaki Y, Mori H, et al. Cell size and nucleoid organization of engineered Escherichia coli cells with a reduced genome. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55(1):137–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stano P, D’Aguanno E, Bolz J, Fahr A, Luisi PL. A remarkable self-organization process as the origin of primitive functional cells. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013 doi: 10.1002/anie.201306613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54*.Budin I, Debnath A, Szostak JW. Concentration-driven growth of model protocell membranes. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(51):20812–9. doi: 10.1021/ja310382d. Development and characterization of a cell-free system to host the minimal components of life.

- 55.Porcar M, Danchin A, de Lorenzo V, Dos Santos VA, Krasnogor N, Rasmussen S, Moya A. The ten grand challenges of synthetic life. Syst Synth Biol. 2011;5(1-2):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11693-011-9084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Noirel J, Ow SY, Sanguinetti G, Wright PC. Systems biology meets synthetic biology: a case study of the metabolic effects of synthetic rewiring. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5(10):1214–23. doi: 10.1039/b904729h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carothers JM, Goler JA, Juminaga D, Keasling JD. Model-driven engineering of RNA devices to quantitatively program gene expression. Science. 2011;334(6063):1716–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1212209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carbonell P, Planson AG, Fichera D, Faulon JL. A retrosynthetic biology approach to metabolic pathway design for therapeutic production. BMC Syst Biol. 2011;5:122. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lux MW, Bramlett BW, Ball DA, Peccoud J. Genetic design automation: engineering fantasy or scientific renewal? Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30(2):120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen J, Densmore D, Ham TS, Keasling JD, Hillson NJ. DeviceEditor visual biological CAD canvas. J Biol Eng. 2012;6(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moses T, Pollier J, Almagro L, Buyst D, Van Montagu M, Pedreno MA, Martins JC, Thevelein JM, Goossens A. Combinatorial biosynthesis of sapogenins and saponins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a C-16alpha hydroxylase from Bupleurum falcatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(4):1634–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323369111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jacobsen JH, Frigaard NU. Engineering of photosynthetic mannitol biosynthesis from CO2 in a cyanobacterium. Metab Eng. 2014;21:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakagawa A, Minami H, Kim JS, Koyanagi T, Katayama T, Sato F, Kumagai H. A bacterial platform for fermentative production of plant alkaloids. Nat Commun. 2011;2:326. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choi YJ, Lee SY. Microbial production of short-chain alkanes. Nature. 2013;502(7472):571–4. doi: 10.1038/nature12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cui YY, Ling C, Zhang YY, Huang J, Liu JZ. Production of shikimic acid from Escherichia coli through chemically inducible chromosomal evolution and cofactor metabolic engineering. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Anderson JC, Dueber JE, Leguia M, Wu GC, Goler JA, Arkin AP, Keasling JD. BglBricks: A flexible standard for biological part assembly. J Biol Eng. 2010;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1754-1611-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Quan J, Tian J. Circular polymerase extension cloning of complex gene libraries and pathways. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Engler C, Kandzia R, Marillonnet S. A one pot, one step, precision cloning method with high throughput capability. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kirchmaier S, Lust K, Wittbrodt J, Centre for Organismal S Golden GATEway cloning - a combinatorial approach to generate fusion and recombination constructs. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li MZ, Elledge SJ. Harnessing homologous recombination in vitro to generate recombinant DNA via SLIC. Nat Methods. 2007;4(3):251–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Itaya M, Fujita K, Kuroki A, Tsuge K. Bottom-up genome assembly using the Bacillussubtilis genome vector. Nat Methods. 2008;5(1):41–3. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Benders GA, Noskov VN, Denisova EA, Lartigue C, Gibson DG, Assad-Garcia N, Chuang RY, Carrera W, Moodie M, Algire MA, et al. Cloning whole bacterial genomes in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(8):2558–69. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]