Abstract

Objective

Examine the relationship between left ventricular mass (LVM) regression and clinical outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Background

LVM regression after valve replacement for aortic stenosis (AS) is assumed to be a favorable effect of LV unloading, but its relationship to improved clinical outcomes is unclear.

Methods

Of 2115 patients with symptomatic AS at high surgical risk receiving TAVR in the PARTNER randomized trial or continued access registry, 690 had both severe LVH (LVM index [LVMi] ³149 g/m2 men, ³122 g/m2 women) at baseline and an LVMi measurement 30 days post-TAVR. Clinical outcomes were compared for patients with greater than vs. lesser than median percent change in LVMi between baseline and 30 days using Cox proportional hazard models to evaluate event rates from 30 to 365 days.

Results

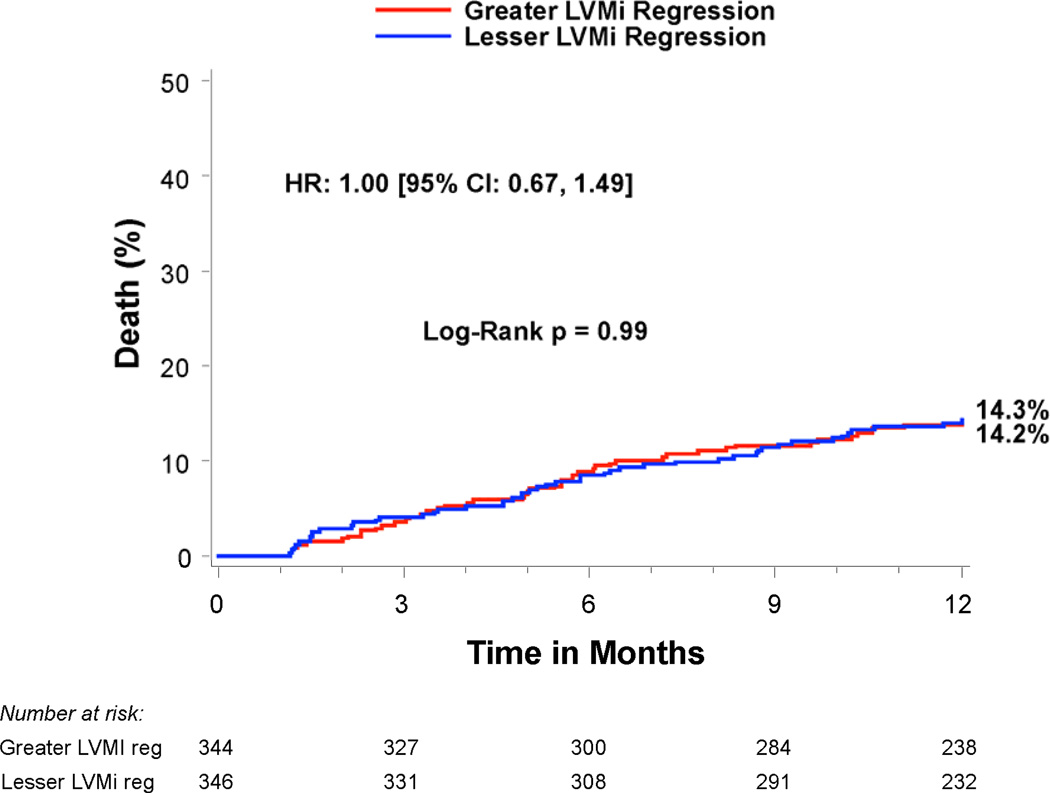

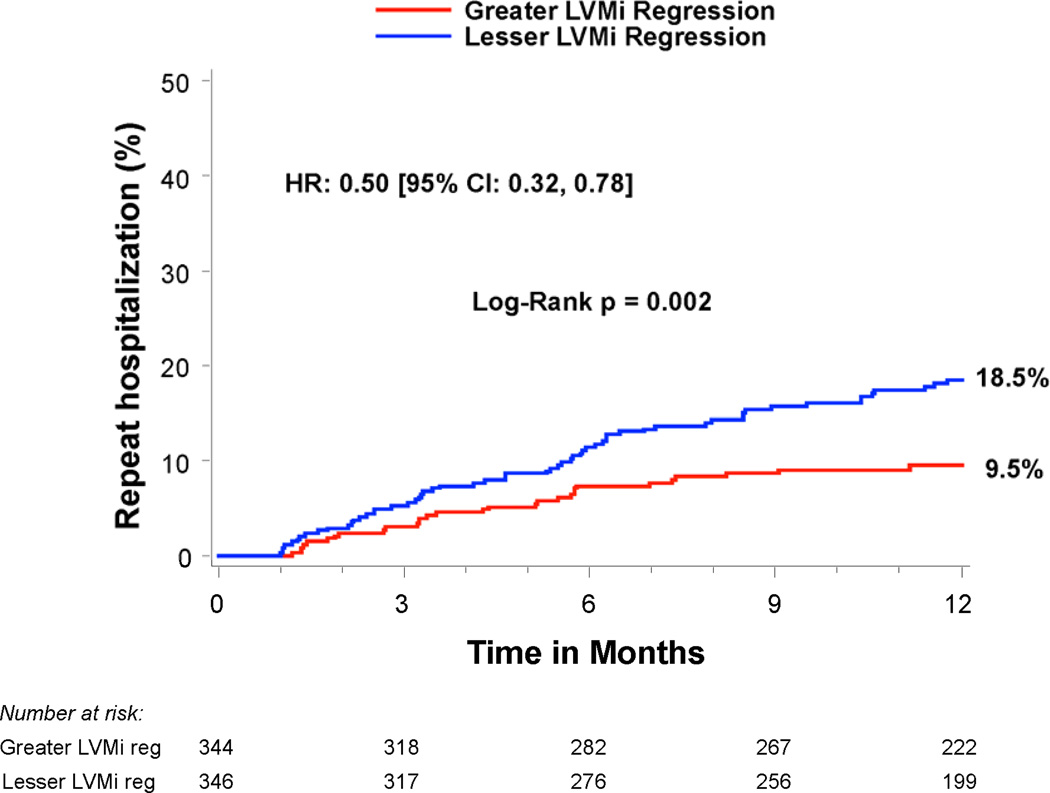

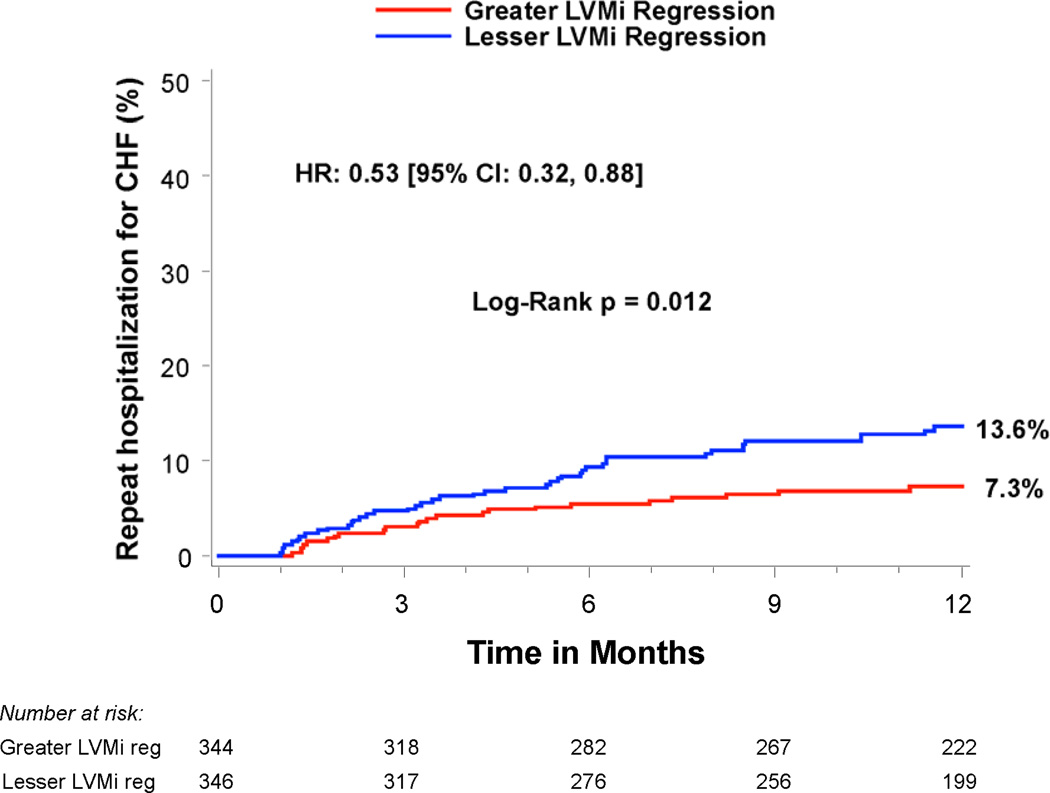

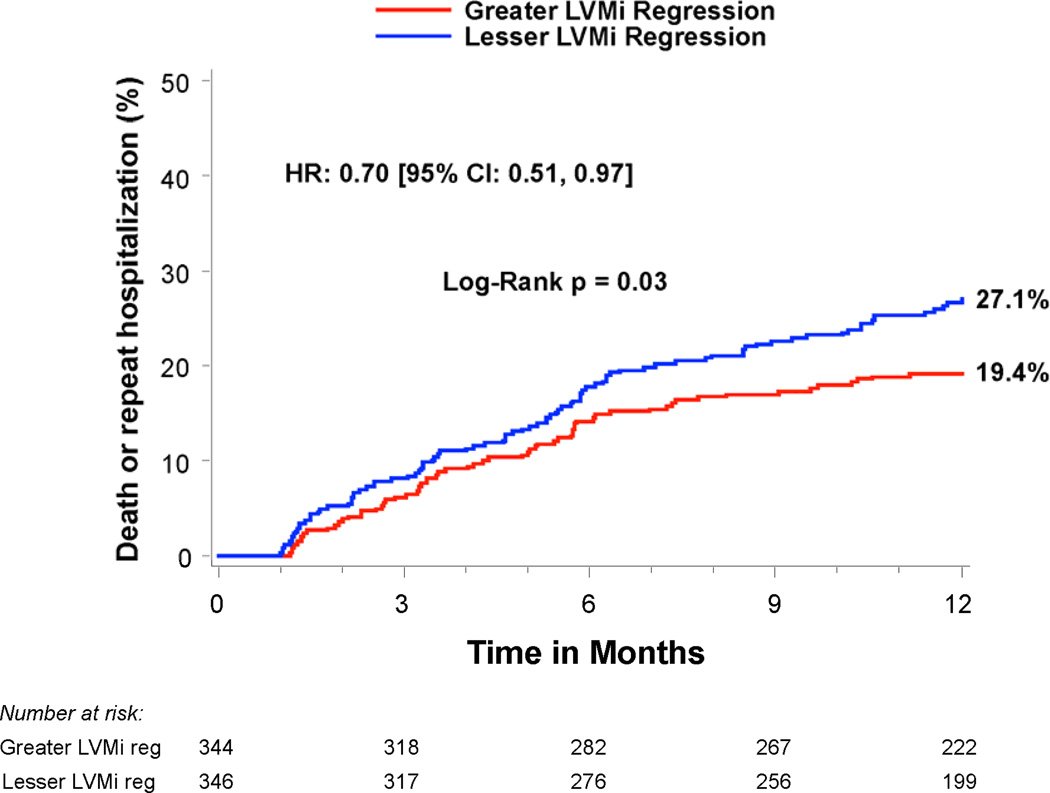

Compared to patients with lesser regression, patients with greater LVMi regression had a similar rate of all-cause mortality (14.1% vs. 14.3%, p=0.99), but a lower rate of rehospitalization (9.5% vs. 18.5%, HR 0.50; 95% CI, 0.32–0.78; p=0.002) and a lower rate of rehospitalizations specifically for heart failure (7.3% vs. 13.6%, p=0.01). The association with a lower rate of hospitalizations was consistent across sub-groups and remained significant after multivariable adjustment (HR 0.53; 95% CI, 0.34–0.84; p=0.007). Patients with greater LVMi regression had lower BNP (p=0.002) and a trend toward better quality of life (p=0.06) at 1 year compared to those with lesser regression.

Conclusions

In high-risk patients with severe AS and severe LVH undergoing TAVR, those with greater early LV mass regression had half the rate of rehospitalization over the subsequent year.

Keywords: aortic stenosis, transcatheter aortic valve replacement, hypertrophic LV remodeling, hospitalizations, heart failure

Introduction

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), defined by increased LV mass (LVM), is associated with increased mortality and morbidity in a broad spectrum of disorders, including patients with severe calcific aortic stenosis (AS) undergoing valve replacement surgery (1–3). LVM regression after valve replacement for AS is presumed to be a favorable effect of left ventricular (LV) unloading (4). A number of studies have evaluated the extent and timing of LVM regression after surgical valve replacement and it is often used as a criterion by which to compare the performance of prosthetic valves (5–9). However, the widely held axiom of a relationship between greater LVM regression and improved clinical outcomes has not been clearly established and some findings undercut it (10). In addition, these issues have not been studied extensively in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

Accordingly, we examined the clinical outcomes of patients with severe symptomatic AS at high risk for surgery (Cohort A) enrolled in the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) randomized trial and those in the continued access registry to evaluate whether outcomes varied according to the amount of LVM regression after treatment with TAVR (11). Because the presence of more marked LVH prior to valve replacement portends worse clinical outcomes, we evaluated patients with severe LVH on their baseline pre-procedure echocardiogram.

Methods

Study population

The design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and primary results of the high-risk cohort (Cohort A) of the PARTNER randomized clinical trial have been reported (11). The inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients enrolled in the high-risk continued access registry were the same as those enrolled in the Cohort A randomized trial. These patients had severe AS with an aortic valve area (AVA) <0.8 cm2 (or indexed AVA <0.5 cm2/m2) and either resting or inducible mean gradient >40 mmHg or peak jet velocity >4 m/s. They were symptomatic from AS (NYHA functional class ≥2) and were at high surgical risk as defined by a predicted risk of death of 15% or higher by 30 days after conventional surgery. After evaluation of vascular anatomy, patients were included in either the transfemoral cohort or transapical cohort and, if enrolled in the trial, randomized to transcatheter therapy with the Edwards-SAPIEN heart valve system (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, California) or surgical aortic valve replacement. For this analysis, we included only patients who received treatment with TAVR (the “as treated” population) who also had: 1) severe LVH on the baseline echocardiogram (ASE sex-specific cut-offs of LVM index [LVMi] ≥149 g/m2 men, ≥122 g/m2 women); and 2) echocardiograms performed at baseline and 30 days post-TAVR with LVMi measured. Clinical characteristics were determined by the enrolling sites. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each enrolling site and all patients provided written informed consent.

Echocardiography

An independent core laboratory analyzed all echocardiograms as previously described (12,13). LV mass was calculated using the formula recommended by the ASE and indexed to body surface area (12,14,15). Relative wall thickness was calculated in two ways: [(posterior wall thickness × 2) / LV end-diastolic dimension] and [(posterior wall thickness + septal wall thickness) / LV end-diastolic dimension], in which the septal wall thickness was measured at the basal septal bulge. Stroke volume was calculated as the LV outflow tract area multiplied by the pulsed wave Doppler LV outflow tract velocity-time integral and indexed to BSA. Moderate prosthesis-patient mismatch (PPM) was defined as an effective orifice area index 0.65–0.85 cm2/m2 and severe PPM as an effective orifice area index <0.65 cm2/m2. The presence and severity of post-procedural aortic regurgitation were determined according to VARC-2 criteria (16). Per protocol, echocardiograms were obtained at baseline (within 45 days of TAVR), and post-TAVR at discharge (or 7 days), 30 days, 6 months, and 1 year (12).

Clinical endpoints

Clinical events including all-cause death, cardiac death, repeat hospitalizations, stroke, renal failure, major bleeding, myocardial infarction, and vascular complications were adjudicated by a clinical events committee (11). Repeat hospitalizations were defined as hospitalization for complications from TAVR (eg. renal failure, infection, etc.) or symptoms of heart failure, angina, or syncope due to aortic valve disease requiring aortic valve intervention or intensified medical management. Stroke was defined as a focal neurologic deficit lasting ≥24 hours or a focal neurologic deficit lasting <24 hours with imaging findings of acute infarction or hemorrhage. Renal failure events were defined as the need for dialysis of any sort. The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), a heart failure disease-specific health status measure, was used to assess health status (17,18).

Statistical analysis

The effect of LVMi regression was evaluated by comparing patients with severe LVH at baseline with greater vs. lesser decrease in LVMi between baseline and 30 days post-TAVR. The groups were determined based on the median % decrease for each sex, so that females with greater than the median sex-specific % decrease in LVMi were combined with the males with greater than the median sex-specific % decrease in LVMi into a combined greater LVMi regression group. Continuous variables were summarized as mean±SD or medians and quartiles, and were compared using the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney rank sum test as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared with the chi-square or Fisher exact test. Changes in LVMi over time were evaluated by an overall F-test to examine trend and a paired t-test was used to compare individual time points. A Student’s two sample t-test was used to compare change in LVMi between groups. Receiver operating characteristic analysis was performed utilizing Youden’s index criterion to determine the optimal cut-point for % LVMi regression for predicting repeat hospitalizations. Survival curves for time-to-event variables, based on all available follow-up data, were performed with the use of Kaplan-Meier estimates and were compared between groups with the use of the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate hazard ratios and to test for interactions. Stepwise Cox models (entry/stay criteria 0.10/0.10) evaluated the relationship between greater vs. lesser LVMi regression (from baseline to 30 days) and repeat hospitalizations (from 30 days to 1 year) after adjustment for clinical and echocardiographic variables that had a univariable association (p≤0.10) with repeat hospitalizations. Linear regression models evaluated clinical and echocardiographic predictors of percent change in LVMi from baseline to 30 days. KCCQ overall summary scores were compared using analysis of covariance to adjust for baseline differences in KCCQ scores between groups. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.2.

Results

Patient population

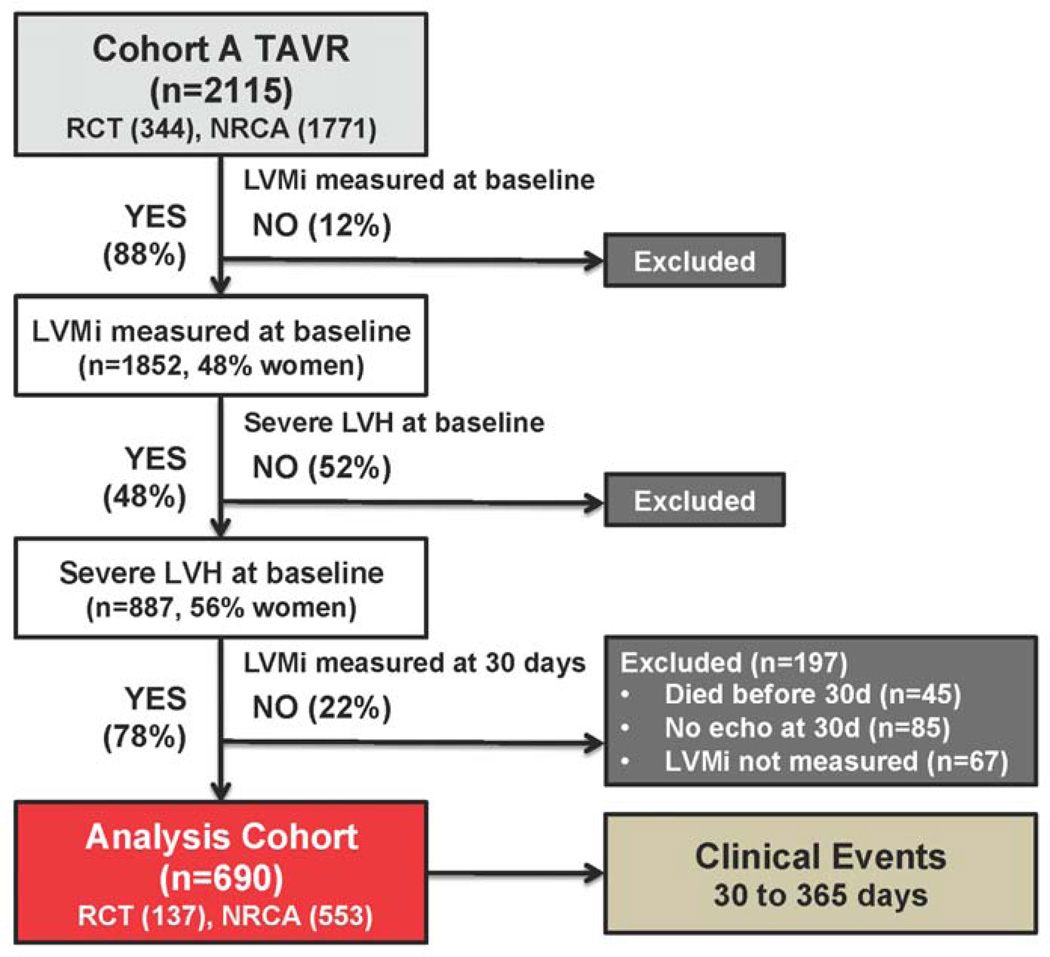

Among the 2115 patients with symptomatic AS at high surgical risk receiving TAVR in the PARTNER randomized trial or continued access registry, 1852 (48% female) had LVMi measured at baseline and 887 (40% of males and 57% of females with LVMi measured at baseline) had severe LVH (Figure 1). Of those with severe LVH at baseline, 690 patients (n=137 randomized; n=553 registry) also had LVMi measured on the echocardiogram obtained 30 days after TAVR, which formed the population for this study; 197 patients did not have LVMi measured 30 days after TAVR due to death (n=45), no echocardiogram obtained (n=85), or LVMi was not measured due to poor image quality (n=67). A transfemoral approach was utilized in 55% of patients and the remainder were treated via a transapical approach. The study population had a mean age of 85±7 years, AVA 0.65±0.20 cm2, STS score of 11.0 (9.7, 13.0) and 56% were female.

Figure 1. Flow diagram for subjects included in the analysis.

Abbreviations: TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; RCT, randomized controlled trial; NRCA, non-randomized continued access registry; LVMi, left ventricular mass index; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy.

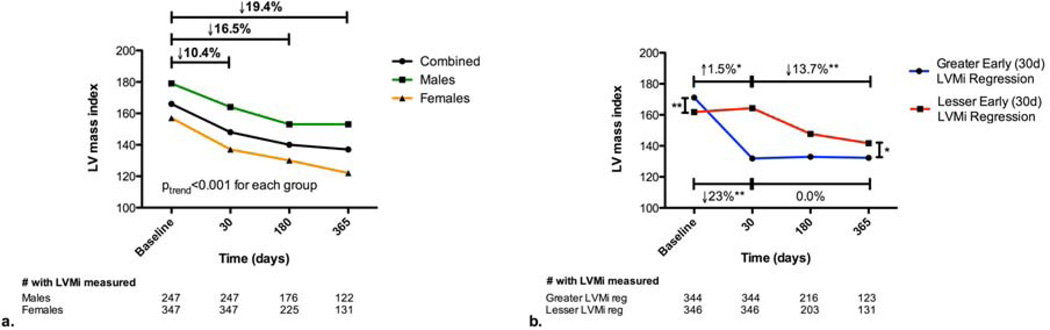

Regression of LVMi

Among patients with severe LVH at baseline that survived 1 year after TAVR, LVMi decreased from 166±31 g/m2 (baseline) to 137±35 g/m2 (1 year) (p<0.001) (Figure 2a). LVMi regression over the first year post-TAVR occurred in both males and females (p<0.001 for each) with a similar pattern of incremental regression, but the overall percent LVMi regression was greater among females (p=0.004). Over half of the LVMi regression observed in this population occurred by 30 days (Figure 2a). Compared to those with lesser LVMi regression at 30 days, those with greater LVMi regression had a higher baseline LVMi, but lower LVMi at 30 days, 6 months, and 1 year (p<0.05 for each comparison) (Figure 2b). Those with greater LVMi regression at 30 days had no change in LVMi during the remainder of the year (p=0.22), whereas those with lesser LVMi regression at 30 days had significant regression during the remainder of the year (p<0.001) (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Regression of Left Ventricular Mass Index after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients with Severe Left Ventricular Hypertrophy.

Left ventricular mass index (LVMi) regression is shown for patients (combined, men, and women) who had severe LVH at baseline and survived at least 1 year after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) (a). The pattern of change in LVMi over 1 year after TAVR is shown for patients with severe LVH at baseline who had greater vs. lesser change in LVMi from baseline to 30 days post-TAVR (based on sex-specific median % change in LVMi) (b). The mean LVMi from all available echoes at each time point is shown. *p<0.001. **p<0.05.

Patients with greater early LVMi regression had lower baseline prevalences of obesity (p=0.05) and permanent pacemaker implantation (p=0.01) than those with lesser regression (Table 1). Baseline echocardiographic variables were also significantly different between groups (Table 2). In the greater LVMi regression group there was greater midwall fractional shortening (p<0.001), a thicker posterior wall (PWT) (p = 0.02) resulting in greater relative wall thickness by the PWT calculation (p = 0.04), and a strong trend toward a higher mean transvalvular gradient (p = 0.057). There was no baseline difference in LV dimensions, ejection fraction or stroke volume index. Following TAVR, the greater LVMi regression group had smaller LV dimensions (p<0.01), wall thickness (p<0.001) and relative wall thickness (p<0.01). There was also significantly less moderate or severe prosthesis-patient mismatch in the greater LVMi regression group (p=0.04). Greater early LVMi regression was associated with increased relative wall thickness at baseline, but decreased relative wall thickness on the 30 day post-TAVR echocardiogram, suggesting that the mass regression resulted from a relatively greater decrease in wall thickness than decrease in LV cavity dimension. In multivariable analysis including clinical and echocardiographic variables (at baseline and 30 days post-TAVR), female sex, absence of a pacemaker, higher LVMi, and greater midwall fractional shortening at baseline, and lower transvalvular mean gradient 30 days post-TAVR were independently associated with greater early LVMi regression (Table 3).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics based on Early Regression of Severe LVH after TAVR

| TAVR A (RCT + NRCA) n=690 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Greater LVMi Regression (n=344) |

Lesser LVMi Regression (n=346) |

p-value | |

| Age | 85.5 ± 6.1 | 84.7 ± 6.9 | 0.11 |

| Female | 56% | 56% | 0.99 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.8 ± 5.5 | 27.0 ± 6.4 | 0.009 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30) | 18.9% | 25.1% | 0.05 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.74 ± 0.23 | 1.78 ± 0.24 | 0.02 |

| STS Score | 11.7 ± 3.9 | 12.3 ± 5.6 | 0.08 |

| STS >10 | 68% | 70% | 0.44 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE | 28.0 ± 15.8 | 28.7 ± 17.3 | 0.58 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 83% | 83% | 0.95 |

| Smoking | 45% | 47% | 0.64 |

| Hypertension | 92% | 95% | 0.21 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 34% | 41% | 0.056 |

| NYHA class 4 | 47% | 46% | 0.88 |

| Angina | 16% | 20% | 0.21 |

| Coronary disease | 74% | 78% | 0.23 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 29% | 30% | 0.84 |

| Prior PCI | 42% | 38% | 0.26 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass surgery | 41% | 46% | 0.16 |

| Stroke or TIA (last 6–12 months) | 26% | 31% | 0.10 |

| Carotid disease | 27% | 30% | 0.42 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 43% | 43% | 0.96 |

| Porcelain aorta | 0.3% | 0.9% | 0.62 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 42% | 40% | 0.59 |

| Major arrhythmia | 49% | 55% | 0.09 |

| Permanent pacemaker | 18% | 26% | 0.01 |

| Renal disease (creatinine ≥2) | 16% | 20% | 0.15 |

| Liver disease | 1.7% | 2.0% | 0.79 |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 38% | 41% | 0.43 |

| Oxygen dependent | 8.1% | 7.8% | 0.87 |

| Anemia | 71% | 69% | 0.52 |

| Transfemoral TAVR | 53% (182/344) | 58% (200/346) | 0.20 |

Greater vs. lesser LVMi regression defined by sex-specific median % change in LVMi from baseline to 30 days post-TAVR.

Abbreviations: TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; RCT, randomized controlled trial; NRCA, non-randomized continued access registry; LVMi, left ventricular mass index; BMI, body mass index; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgery; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic Characteristics based on Early Regression of Severe LVH after TAVR

| TAVR A (RCT + NRCA) n=690 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Greater LVMi Regression (n=344) |

Lesser LVMi Regression (n=346) |

p-value | |

| Baseline Echo Variables | |||

| LVMi (g/m2) | 171 ± 32 | 162 ± 28 | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 50 ± 13 | 49 ± 14 | 0.13 |

| Midwall fractional shortening (%) | 13.5 ± 8.0 | 11.3 ± 6.8 | <0.001 |

| Stroke Volume Index (ml/m2) | 38 ± 11 | 37 ± 11 | 0.17 |

| LV end-diastolic dimension (cm) | 4.68 ± 0.77 | 4.72 ± 0.76 | 0.40 |

| LV end-systolic dimension (cm) | 3.46 ± 0.96 | 3.53 ± 0.94 | 0.34 |

| LV posterior wall dimension (cm) | 1.28 ± 0.28 | 1.23 ± 0.26 | 0.02 |

| LV septal wall dimension (cm) | 1.76 ± 0.28 | 1.72 ± 0.33 | 0.09 |

| Relative wall thickness (PWT only) | 0.57 ± 0.19 | 0.54 ± 0.18 | 0.04 |

| Relative wall thickness (PWT and SWT) | 0.68 ± 0.19 | 0.65 ± 0.19 | 0.08 |

| LVOT dimension (cm) | 2.02 ± 0.19 | 2.03 ± 0.19 | 0.46 |

| AVA index (cm2/m2) | 0.37 ± 0.10 | 0.37 ± 0.11 | 0.67 |

| AV mean gradient (mmHg) | 47 ± 15 | 44 ± 15 | 0.057 |

| Moderate and severe total AR | 12.8% | 10.2% | 0.28 |

| Moderate and severe MR | 24.9% | 22.4% | 0.46 |

| Post-TAVR Echo Variables (30 days) | |||

| LVMi (g/m2) | 132 ± 27 | 164 ± 32 | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 53 ± 12 | 52 ± 12 | 0.34 |

| Midwall fractional shortening (%) | 13.8 ± 8.2 | 13.2 ± 6.9 | 0.27 |

| Stroke Volume Index (ml/m2) | 39 ± 12 | 39 ± 12 | 0.75 |

| LV end-diastolic dimension (cm) | 4.58 ± 0.79 | 4.80 ± 0.81 | <0.001 |

| LV end-systolic dimension (cm) | 3.32 ± 0.94 | 3.51 ± 0.93 | 0.006 |

| LV posterior wall dimension (cm) | 1.10 ± 0.23 | 1.22 ± 0.27 | <0.001 |

| LV septal wall dimension (cm) | 1.52 ± 0.27 | 1.69 ± 0.32 | <0.001 |

| Relative wall thickness (PWT only) | 0.50 ± 0.16 | 0.53 ± 0.18 | 0.01 |

| Relative wall thickness (PWT and SWT) | 0.60 ± 0.17 | 0.63 ± 0.19 | 0.008 |

| EOA index (cm2/m2) | 0.99 ± 0.29 | 0.96 ± 0.29 | 0.10 |

| PPM (moderate and severe) | 33.5% | 41.3% | 0.04 |

| PPM (severe) | 10.0% | 12.7% | 0.27 |

| AV mean gradient (mmHg) | 9 ± 4 | 10 ± 5 | 0.10 |

| Mild total AR | 49.4% | 52.3% | 0.45 |

| Moderate and severe total AR | 12.5% | 14.2% | 0.52 |

| Moderate and severe MR | 19.5% | 21.1% | 0.61 |

Greater vs. lesser LVMi regression defined by sex-specific median % change in LVMi from baseline to 30 days post-TAVR. Moderate PPM = EOA index 0.65–0.85 cm2/m2. Severe PPM = EOA index <0.65 cm2/m2.

Abbreviations: PWT, posterior wall thickness; SWT, septal wall thickness; EOA, effective orifice area; PPM, prosthesis-patient mismatch; AV, aortic valve; AR, aortic regurgitation; MR, mitral regurgitation; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Table 3.

Multivariable Linear Regression Models for Percent Change in LVMi from Baseline to 30 days after TAVR

| Variable | β-estimate (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 – Clinical Model | ||

| Intercept | −9.0 | 0.28 |

| Age (per year) | 0.1 | 0.48 |

| Male sex | −5.7 | <0.001 |

| Baseline LVMi (per 1 g/m2 increase) | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| STS score (per 1 unit increase) | −0.3 | 0.02 |

| Pacemaker at baseline | −3.1 | 0.02 |

| Model 2 – Clinical + Baseline Echo | ||

| Intercept | −17.9 | 0.04 |

| Age (per year) | 0.1 | 0.36 |

| Male sex | −5.7 | <0.001 |

| Baseline LVMi (per 1 g/m2 increase) | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| STS score (per 1 unit increase) | −0.2 | 0.09 |

| Pacemaker at baseline | −2.9 | 0.04 |

| Midwall fractional shortening (per 1% increase) | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 – Clinical + Baseline Echo + 30d Echo | ||

| Intercept | −17.2 | 0.05 |

| Age (per year) | 0.1 | 0.30 |

| Male sex | −5.7 | <0.001 |

| Baseline LVMi (per 1 g/m2) | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| STS score (per 1 unit) | −0.2 | 0.07 |

| Pacemaker at baseline | −3.2 | 0.02 |

| Midwall fractional shortening (per 1% increase) | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| 30 day transvalvular mean gradient (per 1 mmHg increase) | −0.3 | 0.05 |

Linear regression models evaluating variables associated with % D in LVMi from baseline to 30 days post-TAVR. A positive β signifies regression/decrease in LVMi from baseline to 30 days post-TAVR.

Model 1: Selection model including age, sex, and baseline LVMi (forced variables) and other variables selected from among the clinical variables (Table 1) that differ (p≤0.10) between those with greater vs. lesser regression at 30 days.

Model 2: Selection model including the same variables as Model 1 in addition to baseline echo variables (Table 2) that differ (p≤0.10) between those with greater vs. lesser regression at 30 days (variables were excluded if they were a part of the calculation of LVMi).

Model 3: Selection model including the same variables as Model 2 in addition to 30 day post-TAVR echo variables (Table 2) that differ (p≤0.10) between those with greater vs. lesser regression at 30 days (variables were excluded if they were a part of the calculation of LVMi).

Abbreviations: STS, Society of Thoracic Surgery; LVMi, left ventricular mass index.

Clinical outcomes

Compared to patients with lesser regression, patients with greater LVMi regression 30 days after TAVR had a similar rate of all-cause mortality between 30 days and 1 year (14.1% vs. 14.3%, p=0.99), but a lower rate of rehospitalization (9.5% vs. 18.5%, HR 0.50; 95% CI, 0.32–0.78; p=0.002) and the composite endpoint of death or rehospitalization (19.4% vs. 27.1%, HR 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51–0.97; p=0.03) (Table 4 and Figure 3). In particular, greater early LVMi regression was associated with a lower rate of repeat hospitalizations for heart failure (7.3% vs. 13.6%, HR 0.53; 95% CI, 0.32–0.88; p=0.01), which was the most common reason for repeat hospitalization in these patients (Table 4 and Figure 3c). The strong association of greater early LVMi regression with a lower rate of repeat hospitalizations was consistent across several sub-groups with no significant interactions (Table 5), and remained essentially unchanged after extensive multivariable adjustment for clinical and echocardiographic factors associated with repeat hospitalizations (Table 6 and Supplemental Table 1). Receiver operating characteristic analysis demonstrated that an early LVMi regression of 10% was the optimal cut-off for predicting repeat hospitalizations (AUC 0.60, 95% CI, 0.53–0.66). Greater early LVMi regression was also associated with a lower rate of repeat hospitalization between 30 days and 1 year when we evaluated patients with moderate or severe baseline LVH (11.5% vs. 18.4%, HR 0.62; 95% CI, 0.43–0.88; p=0.007) or patients with any degree of baseline LVH (12.6% vs. 16.8%, HR 0.75; 95% CI, 0.55–1.03; p=0.07) (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3).

Table 4.

Clinical Outcomes Based on Early Regression of Severe LVH after TAVR

| Clinical Outcome | Greater LVMi Regression % (no.) |

Lesser LVMi Regression % (no.) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes 30 days to 1 year Combined | n=344 | n=346 | ||

| Death (all-cause) | 14.1% (47) | 14.3% (48) | 1.00 [0.67,1.49] | 0.99 |

| Death (cardiac) | 8.8% (28) | 9.3% (30) | 0.95 [0.57,1.59] | 0.84 |

| Repeat hospitalizations | 9.5% (30) | 18.5% (59) | 0.50 [0.32,0.78] | 0.002 |

| Hospitalizations for CHF | 7.3% (23) | 13.6% (43) | 0.53 [0.32,0.88] | 0.01 |

| Death or hospitalizations | 19.4% (65) | 27.1% (91) | 0.70 [0.51,0.97] | 0.03 |

| Stroke (any) | 1.3% (4) | 1.6% (5) | 0.81 [0.22,3.03] | 0.76 |

| Outcomes 30 days to 1 year Males | n=151 | n=152 | ||

| Death (all-cause) | 18.4% (27) | 20.0% (29) | 0.94 [0.55,1.58] | 0.81 |

| Death (cardiac) | 10.9% (15) | 13.1% (18) | 0.83 [0.42,1.66] | 0.60 |

| Repeat hospitalizations | 13.6% (19) | 23.3% (32) | 0.57 [0.32,1.01] | 0.051 |

| Death or hospitalizations | 24.4% (36) | 35.5% (52) | 0.67 [0.44,1.02] | 0.059 |

| Stroke (any) | 1.5% (2) | 0.7% (1) | 2.03 [0.18,22.43] | 0.55 |

| Outcomes 30 days to 1 year Females | n=193 | n=194 | ||

| Death (all-cause) | 10.7% (20) | 9.9% (19) | 1.07 [0.57,2.00] | 0.83 |

| Death (cardiac) | 7.2% (13) | 6.4% (12) | 1.10 [0.50,2.42] | 0.81 |

| Repeat hospitalizations | 6.2% (11) | 15.0% (27) | 0.40 [0.20,0.81] | 0.009 |

| Death or hospitalizations | 15.5% (29) | 20.6% (39) | 0.74 [0.46,1.19] | 0.21 |

| Stroke (any) | 1.1% (2) | 2.3% (4) | 0.51 [0.09,2.78] | 0.43 |

| Outcomes 0–30 days | n=344 | n=346 | ||

| Post-TAVR myocardial infarct | 0.9% (3) | 0.6% (2) | 1.51 [0.25,9.04] | 0.65 |

| Major bleeding | 5.8% (20) | 6.9% (24) | 0.83 [0.46,1.51] | 0.54 |

| Major vascular complication | 5.8% (20) | 4.9% (17) | 1.18 [0.62,2.26] | 0.60 |

| Renal failure requiring dialysis | 2.3% (8) | 0.9% (3) | 2.70 [0.72,10.19] | 0.13 |

| Stroke (any) | 2.3% (8) | 3.5% (12) | 0.67 [0.27,1.64] | 0.37 |

Greater vs. lesser LVMi regression defined by sex-specific median % change in LVMi from baseline to 30 days post-TAVR.

The event rates were calculated with the use of Kaplan-Meier methods.

Abbreviations: LVMi, left ventricular mass index; CHF, congestive heart failure; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Figure 3. Time-to-event curves for death or repeat hospitalizations from 30 days to 1 year.

Time-to-event curves are shown from 30 days to 1 year for a) death (all-cause), b) repeat hospitalizations, c) repeat hospitalizations for heart failure, and d) death (all-cause) or repeat hospitalizations for patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis and severe left ventricular hypertrophy at high surgical risk receiving transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) in the PARTNER randomized trial or continued access registry. The curves compare patients with greater vs. lesser left ventricular mass index (LVMi) regression from baseline to 30 days after TAVR (based on sex-specific median % change in LVMi). The event rates were calculated with the use of Kaplan-Meier methods and compared with the use of the log-rank

Table 5.

Sub-Group Analyses for Repeat Hospitalizations

| Repeat Hospitalizations | Greater LVMi Regression % (no.) |

Lesser LVMi Regression % (no.) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall population | n=344 | n=346 | ||

| Repeat hospitalizations | 9.5% (30) | 18.5% (59) | 0.50 [0.32, 0.78] | 0.002 |

| Trial Group | p for interaction = 0.16 | |||

| TAVR Cohort A RCT | n=63 | n=74 | ||

| 13.8% (8) | 16.3% (11) | 0.90 [0.36, 2.24] | 0.82 | |

| TAVR Cohort A NRCA | n=281 | n=272 | ||

| 8.6% (22) | 19.0% (48) | 0.43 [0.26, 0.71] | 0.0007 | |

| Access Route | p for interaction = 0.54 | |||

| Transfemoral | n=179 | n=197 | ||

| 8.9% (15) | 15.4% (28) | 0.57 [0.30, 1.06] | 0.07 | |

| Transapical | n=165 | n=149 | ||

| 10.1% (15) | 22.6% (31) | 0.43 [0.23, 0.80] | 0.006 | |

| Sex | p for interaction = 0.46 | |||

| Male | n=151 | n=152 | ||

| 13.5% (19) | 23.3% (32) | 0.57 [0.32, 1.01] | 0.05 | |

| Female | n=193 | n=194 | ||

| 6.2% (11) | 15.0% (27) | 0.41 [0.20, 0.82] | 0.009 | |

| Relative wall thickness | p for interaction = 0.12 | |||

| RWT ≥ median | n=186 | n=159 | ||

| 11.0% (19) | 15.5% (23) | 0.71 [0.39, 1.30] | 0.26 | |

| RWT < median | n=158 | n=187 | ||

| 7.5% (11) | 21.0% (36) | 0.35 [0.18,0.68] | 0.001 | |

| LV end-diastolic dimension | p for interaction = 0.40 | |||

| LVEDD ≥ median | n=166 | n=177 | ||

| 14.4% (22) | 24.5% (40) | 0.58 [0.35, 0.98] | 0.04 | |

| LVEDD < median | n=178 | n=169 | ||

| 4.9% (8) | 12.2% (19) | 0.38 [0.17, 0.88] | 0.02 | |

| Ejection fraction | p for interaction = 0.14 | |||

| EF ≥50% | n=216 | n=195 | ||

| 9.6% (19) | 13.6% (24) | 0.71 [0.39, 1.30] | 0.27 | |

| EF <50% | n=127 | n=151 | ||

| 9.3% (11) | 24.8% (35) | 0.36 [0.18, 0.71] | 0.002 | |

| Midwall fractional shortening | p for interaction = 0.48 | |||

| MFS ≥ median | n=177 | n=149 | ||

| 8.5% (14) | 19.0% (26) | 0.45 [0.23,0.86] | 0.01 | |

| MFS < median | n=141 | n=185 | ||

| 10.8% (14) | 17.0% (29) | 0.62 [0.33, 1.18] | 0.14 | |

| Stroke volume index | p for interaction = 0.23 | |||

| SVi ≥35 raL/m2 | n=194 | n=175 | ||

| 7.3% (13) | 18.0% (29) | 0.39 [0.20, 0.75] | 0.003 | |

| SVi <35 mL/m2 | n=144 | n=165 | ||

| 13.0% (17) | 18.9% (29) | 0.68 [0.37, 1.24] | 0.2 | |

| Mean gradient | p for interaction = 0.28 | |||

| MG ≥40 mmHg | n=216 | n=191 | ||

| 6.4% (13) | 15.3% (27) | 0.40 [0.21, 0.78] | 0.005 | |

| MG <40 mmHg | n=122 | n=150 | ||

| 14.6% (16) | 22.5% (31) | 0.66 [0.36, 1.22] | 0.18 | |

| 30 day paravalvular AR | p for interaction = 0.18 | |||

| Mod/severe paravalvular AR | n=38 | n=44 | ||

| 22.4% (8) | 24.6% (10) | 0.92 [0.36, 2.32] | 0.85 | |

| No/trace/mild paravalvular AR | n=306 | n=299 | ||

| 7.8% (22) | 17.4% (48) | 0.44 [0.27, 0.73] | 0.001 | |

Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the hazard ratios for patients in each subgroup for the outcome of repeat hospitalizations and the interaction between each sub-group and LVMi regression (greater vs. lesser regression from baseline to 30 days post-TAVR based on sex-specific median % change in LVMI) for repeat hospitalizations.

Table 6.

Predictors of Repeat Hospitalization (30 Days to 1 Year) Based on Early Regression of Severe LVH after TAVR

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 – Clinical Model | ||

| Greater Early LVMi Regression (baseline to 30 days) | 0.52 (0.33, 0.81) | 0.004 |

| Age (per year) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.12 |

| Male sex | 1.37 (0.87, 2.17) | 0.18 |

| Baseline LVMi (per 1 g/m2 increase) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.39 |

| Major arrhythmia | 1.91 (1.23, 2.96) | 0.004 |

| Prior PCI | 1.70 (1.11, 2.59) | 0.01 |

| Smoking | 1.77 (1.14, 2.76) | 0.01 |

| Model 2 – Clinical and Echocardiographic Model | ||

| Greater Early LVMi Regression (baseline to 30 days) | 0.53 (0.34, 0.84) | 0.007 |

| Age (per year) | 0.97 (0.94, 1.00) | 0.055 |

| Male sex | 1.32 (0.83, 2.10) | 0.23 |

| Baseline LVMi (per 1 g/m2 increase) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.35 |

| Major arrhythmia | 1.74 (1.12, 2.71) | 0.01 |

| Prior PCI | 1.52 (0.99, 2.35) | 0.06 |

| Smoking | 1.81 (1.16, 2.82) | 0.009 |

| Baseline mean gradient (per 1 mmHg increase) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.02 |

| Moderate/severe AR at 30 days | 1.59 (0.99, 2.57) | 0.06 |

Cox PH models evaluating whether greater early left ventricular mass index (LVMi) from baseline to 30 days post-TAVR (based on sex-specific median % change in LVMi) is an independent predictor of the clinical endpoint of repeat hospitalization from 30–365 days.

Model 1: Selection model including age, sex, baseline LVMi, and LVMi regression (greater vs. lesser change in LVMi from baseline to 30 days) (forced variables) and other variables selected from among the baseline clinical variables and clinical events from 0–30 days (myocardial infarction, any stroke, major vascular complication, major bleeding, renal failure requiring dialysis) that have a significant (p≤0.10) univariable relationship with the clinical endpoint of repeat hospitalization from 30–365 days (Supplemental Table 1).

Model 2: Selection model including the same variables as Model 1 in addition to baseline or 30 day echo variables that have a significant (p≤0.10) univariable relationship with the clinical endpoint of repeat hospitalization from 30–365 days (Supplemental Table 1). Echocardiographic variables were excluded if they were a part of the calculation of LVMi (LV cavity dimensions and wall thickness).

Abbreviations: LVMi, left ventricular mass index; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; AR, aortic regurgitation.

BNP, quality of life, and functional status

Although similar at baseline, B-type natriuretic peptide levels were lower at 1 year in patients with greater early LVMi regression compared to those with lesser regression (p=0.002) (Table 7). NYHA functional class was similar between the groups as was the ability to perform a 6 minute walk and the distance walked. After adjustment for baseline differences, there was a trend toward better quality of life at 1 year in patients with greater compared to lesser early regression of severe LVH (p=0.06) (Table 7).

Table 7.

BNP, Symptoms, Quality of Life, and 6 Minute Walk

| Greater LVMi Regression (n=344) |

Lesser LVMi Regression (n=346) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BNP | |||

| Baseline | 862 (398, 2258) | 932 (450, 1927) | 0.92 |

| 30 days | 624 (305, 1497) | 727 (350, 1599) | 0.27 |

| 6 months | 421 (211, 1024) | 562 (243, 1287) | 0.08 |

| 1 year | 356 (186, 824) | 533 (268, 1068) | 0.002 |

| NYHA class III/IV | |||

| Baseline | 94% | 94% | 0.98 |

| Discharge | 35% | 42% | 0.09 |

| 30 days | 18% | 19% | 0.87 |

| 6 months | 10% | 11% | 0.60 |

| 1 year | 8% | 13% | 0.11 |

| KCCQ | |||

| Baseline | |||

| Number of subjects with KCCQ data | n=313 | n=318 | |

| Overall summary score | 42.3 ± 21.8 | 44.7 ± 22.6 | 0.18 |

| 30 days | |||

| Number of subjects with KCCQ data | n=318 | n=314 | |

| Overall summary score adjusted for baseline score | 61.0 ± 24.5 | 62.7 ± 24.4 | 0.75** |

| 6 months | |||

| Number of subjects with KCCQ data | n=278 | n=277 | |

| Overall summary score adjusted for baseline score | 73.2 ± 21.4 | 70.5 ± 23.9 | 0.44** |

| 1 year | |||

| Number of subjects with KCCQ data | n=228 | n=236 | |

| Overall summary score adjusted for baseline score | 73.0 ± 21.2 | 71.5 ± 22.3 | 0.06** |

| 6 minute walk | |||

| Baseline | |||

| Could not perform | 32% | 34% | 0.61 |

| Distance walked (m)* | 151 ± 101 | 166 ± 96 | 0.12 |

| 30 days | |||

| Could not perform | 29% | 29% | 0.19 |

| Distance walked (m) | 187 ± 110 | 180 ± 110 | 0.48 |

| 6 months | |||

| Could not perform | 22% | 24% | 0.55 |

| Distance walked (m) | 206 ± 114 | 209 ± 114 | 0.79 |

| 1 year | |||

| Could not perform | 20% | 22% | 0.47 |

| Distance walked (m) | 201 ± 97 | 200 ± 123 | 0.92 |

Data reported as mean±SD, median (25th, 75th percentiles), or %.

Excluding those who could not perform the 6 minute walk.

Follow-up KCCQ overall summary scores were compared using analysis of covariance to adjust for baseline differences in KCCQ scores between groups.

Abbreviations: LVMi, left ventricular mass index; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire.

Discussion

We found that among patients with severe symptomatic AS at high surgical risk, approximately half of the population had severe LVH at baseline (40% of the males and 57% of the females), and that those with greater LVMi regression 30 days after TAVR had half the rate of repeat hospitalizations from 30 days to 1 year. This was primarily due to a significant decrease in repeat hospitalizations due to heart failure. This association of greater early LVMi regression with fewer hospitalizations was consistent across sub-groups and remained significant after adjustment for clinical and echocardiographic factors associated with repeat hospitalizations. While prior studies have either been inconclusive or undercut the existing dogma, these findings support the assumption that LVH regression after valve replacement for AS is associated with a clinical benefit.

There are several novel aspects to our evaluation of LVMi regression after valve replacement in comparison to prior studies. We looked at a large number of subjects, all of whom were enrolled in a multicenter clinical trial and were treated with TAVR instead of surgical AVR. Echocardiograms were performed at pre-specified consistent intervals for all subjects before TAVR (baseline study) and during follow-up and were all analyzed in a uniform manner by a core laboratory. Given the large patient numbers, we were able to focus our analysis on those with severe LVH in whom the issues of LVMi regression after AVR would presumably be most important. We also had systematic echocardiographic follow-up at 30 days and were, therefore, able to evaluate the impact of early LVMi regression. Finally, a particular strength was our use of adjudicated clinical events, specifically hospitalizations, in all subjects, whereas prior similar studies have been limited to mortality as the only outcome (10).

Regression of LVH after Valve Replacement for AS and its Clinical Implications

LV hypertrophy commonly occurs in patients with chronic LV pressure overload from severe AS. It regresses over months to years after valve replacement (6–8), while some studies have shown that significant LVM regression occurs even earlier (19,20). We showed that in patients with severe LVH treated with TAVR, more than 50% of the 1-year LVMi regression occurred by 30 days. This pattern was consistent for men and women and highlights the remarkable plasticity of the heart, even in this elderly cohort with many comorbidities (21). It was also interesting that those with greater LVMi regression at 30 days did not regress further over the remainder of the year. In contrast, those that had less or no LVMi regression by 30 days experienced LVMi regression between 30 days and 1 year, although they failed to achieve an equivalent degree of regression over the year. LVM is a function of chamber dimensions and wall thickness. We observed that while those with more early regression had smaller LV chamber dimensions and thinner walls at 30 days, the relative wall thickness measurements at baseline and 30 days indicate that there was a greater reduction in the muscle (wall thickness) than the LV chamber dimensions in those patients. After adjusting for baseline LVMi, clinical and echocardiographic variables associated with greater early LVMi regression included female sex, absence of a pacemaker pre-operatively, increased pre-operative midwall fractional shortening, and lower transvalvular mean gradient at 30 days.

Many studies have evaluated LVMi regression after AVR, using it as a surrogate endpoint to compare different valve prostheses; this attests to the widespread assumption that LVMi regression after AVR is a clinically beneficial effect of valve replacement (4,5,9). A few studies suggest clinical benefit from greater post-operative LVMi regression, but significant methodological flaws or small sample size led to inconclusive findings (22,23). In contrast, some studies have reported that greater LVMi regression after AVR is not associated with improved outcome, thus questioning the prevailing dogma (10). For hypertensive patients with LVH, regression of LVH with anti-hypertensive medical therapy has been associated with improved clinical outcomes (24,25). However, such an association has not previously been demonstrated for patients with AS experiencing LVM regression after valve replacement. As such, our finding that greater early LVMi regression is associated with half the rate of repeat hospitalization during the first year after TAVR provides novel and important insight into the connection between regression of LV hypertrophy and clinical outcomes after valve replacement for AS.

Potential Mechanisms for the Relationship between LVMi Regression and Hospitalizations

Greater LVMi regression was associated with a lower rate of repeat hospitalization and the majority of these hospitalizations were related to heart failure. BNP levels were lower at 180 and 365 days in patients who had greater early LVMi regression, consistent with improved LV function and less heart failure in these patients. We hypothesize that more mass regression might have caused improved diastolic function (26,27), but assessment of diastolic function was not included in the core lab echocardiographic measurements (12). Related to this, we speculate that more early LVMi regression might result from less myocardial fibrosis, as suggested by greater midwall fractional shortening at baseline in these patients. LV fibrosis has been associated with impaired systolic function in patients with AS and associated with increased mortality and less symptomatic improvement and LV functional recovery after AVR (28,29).

The event rates for repeat hospitalizations between patients with greater vs. lesser early LVMi regression continued to separate during the entire period from 30 days to 1 year (Figure 1b), suggesting that greater early LVMi regression is associated with ongoing and accumulating clinical benefits. Whether early (30 days) vs. intermediate (6 months) LVMi regression has differential associations with clinical outcomes requires further study. Despite the association between greater LVM regression and fewer hospitalizations, there was no association with cardiac or all-cause mortality. This may be because a 1 year follow-up timeframe is too short to detect differences in mortality, but further studies with longer term follow-up are needed to evaluate this relationship.

Clinical implications

Repeat hospitalizations are a major contributor to healthcare costs and a particular focus of efforts to reduce spending. Our findings demonstrate that greater LVMi regression after valve replacement has important clinical and economic implications. Because of its favorable impact on clinical outcomes, we need to better understand what predicts LVMi regression as well as what may augment it. Our findings suggest that LVMi regression after valve replacement may be a therapeutic target and provide a rationale for identifying adjunctive medical therapy that, in addition to valvular unloading, could accentuate LVMi regression after valve replacement. It is also important to note that in addition to decreasing repeat hospitalizations, greater early LVMi regression was associated with a trend toward improved quality of life at 1 year, an important patient-centered metric of the clinical benefit of TAVR. To our knowledge, this is also the first analysis that specifically evaluates clinical and echocardiographic factors associated with repeat hospitalizations after TAVR and offers insights into other potentially modifiable factors.

Limitations

Echocardiography is not as accurate for assessment of LVM as magnetic resonance imaging, but MRI is much more expensive and was not available in this randomized clinical trial. There may be minor problems with the accuracy of some of the echocardiographic measurements due to image quality or distortions in LV geometry and evaluating the change in LVM may have a wider range of error than evaluating a single measurement. However, these inaccuracies should affect all patients in the study and all echocardiographic measurements were made by a core laboratory (12). Our findings apply to elderly patients at high surgical risk treated with TAVR, whereas they may not apply to younger, lower risk patients, those without severe LVH at baseline, or those treated with surgical valve replacement. Selection bias may also have influenced our results insofar as patients that did not survive 30 days or patients with poor image quality, which precluded measurement of LVMi, were not included in our analysis. Finally, the follow-up time was limited to 1 year because events were not adjudicated beyond this point, which may explain the lack of a relationship between LVMi regression and mortality.

Conclusion

In high-risk patients with severe LVH undergoing TAVR, those with greater early LVMi regression had half the rate of repeat hospitalizations, principally for heart failure, over the first post-procedure year. This association was consistent across sub-groups and remained significant after multivariable adjustment. These findings support the dogma that LVMi regression after valve replacement is associated with clinical benefits, which had previously lacked supporting evidence. The strong association between LVMi regression and reduced hospitalizations has important economic and clinical implications. Further study is needed to elucidate factors associated with LVMi regression and identify adjunctive medical therapies and other interventions that may optimize regression of LVH after valve replacement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maria Alu for her contribution in the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding: The PARTNER Trial was funded by Edwards Lifesciences and the protocol was developed jointly by the sponsor and study steering committee. The present analysis was carried out by academic investigators with no additional funding from Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Lindman is supported by K23 HL116660 and the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant (UL1 TR000448, KL2 TR000450) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AS

aortic stenosis

- KCCQ

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire

- LVH

left ventricular hypertrophy

- LVM

left ventricular mass

- LVMi

left ventricular mass index

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- PARTNER

Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves trial

- PPM

prosthesis-patient mismatch

- TA

transapical

- TAVR

transcatheter aortic valve replacement

- TF

transfemoral

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Lindman is a site co-investigator for the PARTNER Trial. Dr. Pibarot has received an unrestricted research grant from Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Devereux has received honoraria for training courses from Edwards Lifesciences, serves as a consultant for Merck, and serves on an advisory board of GE Medical. Dr. Sarano has received grant support from Abbott Vascular and consulting fees/honoraria from Valtech. Dr. Szeto has received consulting fees/honoraria from MicroInterventional Devices. Dr. Makkar has received grant support from Edwards Lifesciences and St. Jude Medical, is a consultant for Abbott Vascular, Cordis, and Medtronic, and holds equity in Entourage Medical. Dr. Miller has received travel reimbursements from Edwards Lifesciences related to his work as an unpaid member of the PARTNER Trial Executive Committee, and has received consulting fees/honoraria from Abbott Vascular, St. Jude Medical, and Medtronic. Dr. Lerakis has received consulting fees from Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Bowers has received consulting fees/honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo/Eli Lilly and Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Leon has received travel reimbursements from Edwards Lifesciences related to his activities as an unpaid member of the PARTNER Trial Executive Committee. Dr. Douglas has received institutional research support from Edwards Lifesciences. The other authors report no relevant relationships with industry.

References

- 1.Mehta RH, Bruckman D, Das S, et al. Implications of increased left ventricular mass index on in-hospital outcomes in patients undergoing aortic valve surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:919–928. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.116558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mihaljevic T, Nowicki ER, Rajeswaran J, et al. Survival after valve replacement for aortic stenosis: implications for decision making. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:1270–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuster RG, Argudo JA, Albarova OG, et al. Left ventricular mass index in aortic valve surgery: a new index for early valve replacement? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:696–702. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panidis IP, Kotler MN, Ren JF, Mintz GS, Ross J, Kalman P. Development and regression of left ventricular hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1984;3:1309–1320. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(84)80192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pibarot P, Dumesnil JG, Leblanc MH, Cartier P, Metras J. Changes in left ventricular mass and function after aortic valve replacement: a comparison between stentless and stented bioprosthetic valves. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1999;12:981–987. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(99)70152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lund O, Emmertsen K, Dorup I, Jensen FT, Flo C. Regression of left ventricular hypertrophy during 10 years after valve replacement for aortic stenosis is related to the preoperative risk profile. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1437–1446. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lund O, Erlandsen M. Changes in left ventricular function and mass during serial investigations after valve replacement for aortic stenosis. J Heart Valve Dis. 2000;9:583–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monrad ES, Hess OM, Murakami T, Nonogi H, Corin WJ, Krayenbuehl HP. Time course of regression of left ventricular hypertrophy after aortic valve replacement. Circulation. 1988;77:1345–1355. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.6.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walther T, Falk V, Langebartels G, et al. Prospectively randomized evaluation of stentless versus conventional biological aortic valves: impact on early regression of left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation. 1999;100:II6–II10. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.suppl_2.ii-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaudino M, Alessandrini F, Glieca F, et al. Survival after aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis: does left ventricular mass regression have a clinical correlate? Eur Heart J. 2005;26:51–57. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2187–2198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douglas PS, Waugh RA, Bloomfield G, et al. Implementation of echocardiography core laboratory best practices: a case study of the PARTNER I trial. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn RT, Pibarot P, Stewart WJ, et al. Comparison of Transcatheter and Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Severe Aortic Stenosis: A Longitudinal Study of Echocardiography Parameters in Cohort A of the PARTNER Trial (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2514–2521. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:450–458. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Genereux P, et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1438–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds MR, Magnuson EA, Wang K, et al. Health-related quality of life after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: results from the PARTNER (Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve) Trial (Cohort A) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold SV, Spertus JA, Lei Y, et al. Use of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire for monitoring health status in patients with aortic stenosis. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:61–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.970053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christakis GT, Joyner CD, Morgan CD, et al. Left ventricular mass regression early after aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62:1084–1089. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(96)00533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beach JM, Mihaljevic T, Rajeswaran J, et al. Ventricular hypertrophy and left atrial dilatation persist and are associated with reduced survival after valve replacement for aortic stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.016. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill JA, Olson EN. Cardiac plasticity. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1370–1380. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lessick J, Mutlak D, Markiewicz W, Reisner SA. Failure of left ventricular hypertrophy to regress after surgery for aortic valve stenosis. Echocardiography. 2002;19:359–366. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8175.2002.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali A, Patel A, Ali Z, et al. Enhanced left ventricular mass regression after aortic valve replacement in patients with aortic stenosis is associated with improved long-term survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.08.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devereux RB, Wachtell K, Gerdts E, et al. Prognostic significance of left ventricular mass change during treatment of hypertension. JAMA. 2004;292:2350–2356. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okin PM, Devereux RB, Jern S, et al. Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy during antihypertensive treatment and the prediction of major cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2004;292:2343–2349. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamb HJ, Beyerbacht HP, de Roos A, et al. Left ventricular remodeling early after aortic valve replacement: differential effects on diastolic function in aortic valve stenosis and aortic regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:2182–2188. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vizzardi E, D'Aloia A, Fiorina C, et al. Early regression of left ventricular mass associated with diastolic improvement after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25:1091–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weidemann F, Herrmann S, Stork S, et al. Impact of myocardial fibrosis in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2009;120:577–584. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.847772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dweck MR, Joshi S, Murigu T, et al. Midwall fibrosis is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1271–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.