Abstract

Graphene-based nanomaterials have attracted tremendous interest over the past decade due to their unique electronic, optical, mechanical, and chemical properties. However, the biomedical applications of these intriguing nanomaterials are still limited due to their suboptimal solubility/biocompatibility, potential toxicity, and difficulties in achieving active tumor targeting, just to name a few. In this Topical Review, we will discuss in detail the important role of surface engineering (i.e., bioconjugation) in improving the in vitro/in vivo stability and enriching the functionality of graphene-based nanomaterials, which can enable single/multimodality imaging (e.g., optical imaging, positron emission tomography, magnetic resonance imaging) and therapy (e.g., photothermal therapy, photodynamic therapy, and drug/gene delivery) of cancer. Current challenges and future research directions are also discussed and we believe that graphene-based nanomaterials are attractive nanoplatforms for a broad array of future biomedical applications.

Introduction

Graphene, an emerging nanomaterial with single-layered carbon atoms in two dimensions, has attracted tremendous interest since 2004, due to its unique electronic, optical, mechanical, and chemical properties.1−7 Among different subtypes of graphene-based nanomaterials, graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (RGO) have been widely studied in the realm of nanomedicine.8 Owing to their extremely high specific surface area, GO and RGO have been reported to be able to interact with various molecules, such as doxorubicin (DOX) and polyethylenimine (PEI), and have been accepted as excellent platforms for drug delivery and gene transfection.9−16

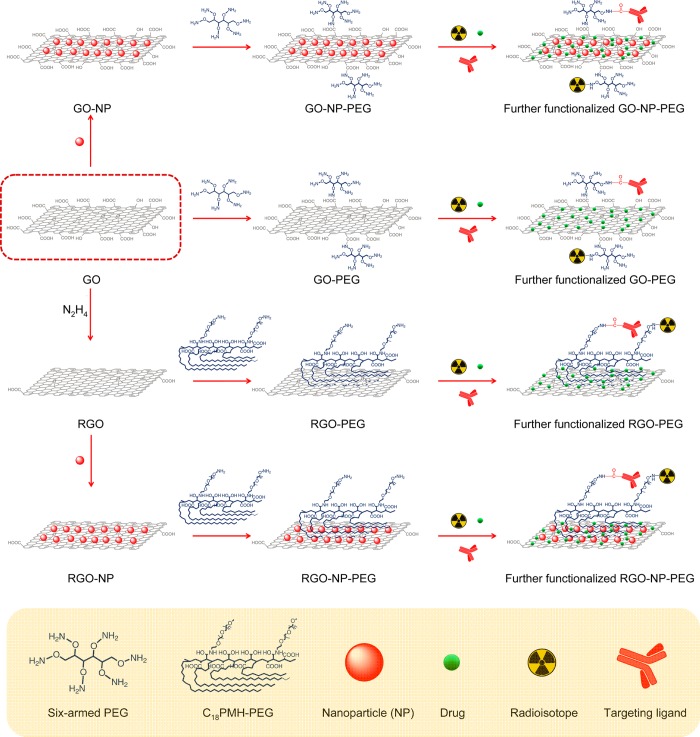

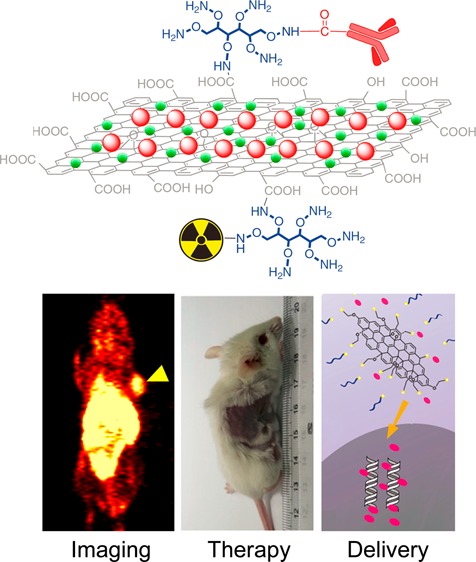

Surface engineering of graphene-based nanomaterials has played a vital role in their biomedical applications.7,8,17 For example, suitable PEGylation could not only improve the solubility and biocompatibility of GO, but also reduce its potential toxicity in vitro as well as in vivo.18−20 After integration with other functional nanoparticles, such as magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs),21−24 gold nanoparticles,25−27 and quantum dots (QDs),28−30 functionalized GO and RGO have also shown great potential for simultaneous cancer imaging and therapy in small animals.30−34 With the conjugation of well-selected targeting ligands, tumor targeted GO (or RGO) has already shown significantly enhanced tumor accumulation in different cancer models in vivo.35−37 Scheme 1 summarizes representative processes of surface functionalization of GO and RGO. In this chapter, we will focus on surface engineering of GO and RGO for biomedical applications.

Scheme 1. Schematic Illustration of Functionalization of Graphene-Based Nanomaterials.

Reproduced with permission from ref (17).

Synthesis of Graphene-Based Nanomaterials

Generally, two methods have been developed for the synthesis of graphene. The first method is a top-down approach, which could cleave multilayer graphite into single layers via mechanical, physical, or chemical exfoliation.38−40 The second method is a bottom-up approach, wherein graphene could be obtained by chemical vapor deposition of one-layer carbon onto well-selected substrates.41−43

So far, oxidative exfoliation via the Hummers method (developed by Hummers and Offeman in 1950s) is the most popular method for the generation of graphene derivatives, such as GO, with great output.44 This technique involves the oxidative exfoliation of graphite using a mixture of potassium permanganate (KMnO4) and concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4). As-produced GO is highly oxidized with a large number of residual epoxides, hydroxides and carboxylic acid groups on its surface. To restore the structure and properties of graphene, GO could be further reduced to obtain RGO by reacting with well-selected reducing agents (e.g., N2H4).45 In comparison with GO, RGO is known to have increased conductive and optical absorbance, making it a more attractive agent for future cancer photothermal therapy.31 For more detailed information about the synthesis of graphene-based nanomaterials, readers are referred to these excellent review papers.40,41

Surface Engineering of Graphene-Based Nanomaterials

To Improve Biocompatibility

As we have mentioned, GO has abundant epoxides, hydroxides, and carboxylic acid groups on its surface, which makes it possible for covalent surface functionalization based on these reactive groups. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is among the most widely used for improving the solubility and biocompatibility of graphene derivatives.18,46,47 By using amine-terminated branched PEG, successful PEGylation of GO has been reported (Figure 1A).10 Intensive sonication was first introduced to break larger GO (size range: 50–500 nm) down to nanographene oxide (nGO) with a significantly reduced size range (i.e., 5–50 nm) (Figure 1B). Six-armed branched PEG was then covalently linked to the carboxylic acid groups on nGO using well-established EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide)/NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) chemistry. The resulting PEGylated nGO (nGO-PEG) exhibited superior stability in biological solutions (Figure 1C). The same PEGylation strategy has been widely used for surface modification of other GO-based nanoparticles, and has shown reduced toxicity in vitro.19,48−52 Besides enhanced biocompatibility and reduced toxicity, GO coated with amine-terminated PEG could also provide abundant amino groups for the further bioconjugations.

Figure 1.

Covalent functionalization of GO by six-armed branched PEG. (A) Schematic illustration of PEGylated GO. (B) Atomic force microscope (AFM) image of GO (top) and nGO-PEG (bottom). (C) Photos of GO (top) and nGO-PEG (bottom) in different solutions recorded after centrifugation at 10000g for 5 min. GO crashed out slightly in PBS and completely in cell medium and serum while nGO-PEG was stable in all solutions. Reproduced with permission from ref (10 and 17).

Many other hydrophilic polymers, including poly(l-lysine) (PLL),53 poly(acrylic acid) (PAA),54 dextran,55,56 and chitosan,57−60 have also been studied for surface functionalization of GO. In one study, GO was functionalized with PLL by stirring GO solution with PLL in the presence of potassium hydroxide (KOH), and subsequently treated with sodium borohydride (NaBH4).53 As-synthesized PLL functionalized GO showed high solubility and biocompatibility, and contained plentiful amino groups. In another work, PAA-coated GO was synthesized via intensive sonication and microwave irradiation.54 Functionalization of PAA could not only improve the biocompatibility of GO but also work as a bridge for linking the fluorescein o-methacrylate (FMA), resulting in fluorescent GO for optical imaging.

Besides covalent surface modification, noncovalent coating via hydrophobic interactions, π–π stacking, and electrostatic interactions are other effective approaches to enabling improved solubility and biocompatibility of graphene derivatives.8 The attachment of PEGylated phospholipids on RGO was completed in one of the first studies of this kind.61 In a follow-up study, PEG-grafted poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-octadecene) (i.e., C18PMH–PEG) was used for nano RGO (nRGO) surface modification via strong hydrophobic interactions between the hydrophobic graphene surface and long hydrocarbon chains in the C18PMH–PEG polymer (Figure 2A and B).31 The solubility of RGO and nRGO in physiological solutions was found to be dramatically enhanced after coating (Figure 2C). In addition, C18PMH–PEG coating was also found helpful for prolonging the blood circulation half-life of functionalized nRGO.62,63 Other agents, including bovine serum albumin (BSA),52 polyoxyethylene sorbitan laurate (Tween),64 Pluronic F127 (PF127),65,66 polyethylenimine (PEI),48 and cholesteryl hyaluronic acid (CHA),12 have also been used for noncovalent surface functionalization of graphene derivatives.

Figure 2.

Noncovalent surface functionalization of RGO with C18PMH-PEG. (A) Schematic illustration of PEGylated RGO and nRGO. (B) AFM images of RGO-PEG (top) and nRGO-PEG (bottom). (C) Photos of RGO, RGO-PEG, nRGO, and nRGO-PEG in water (top), saline (middle), and fetal bovine serum (bottom). RGO and nRGO aggregated slightly in water and completely in saline and serum, whereas RGO-PEG and nRGO-PEG are stable in all solutions. Reproduced with permission from ref (31).

Cancer Imaging with Graphene-Based Nanomaterials

Molecular imaging holds great potential in drug development, disease diagnosis, therapeutic responses monitoring, and the understanding of complex interactions between nanomedicine and living biological systems.67−69 In the past several years, enormous efforts have been devoted to surface engineering of different graphene derivatives for studying their in vivo biodistribution patterns and tumor targeting efficacy using imaging modalities such as optical imaging,28,29,47,70−79 positron emission tomography (PET),35−37,76,80 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),21−24,34,81−83 and others.

Optical Imaging

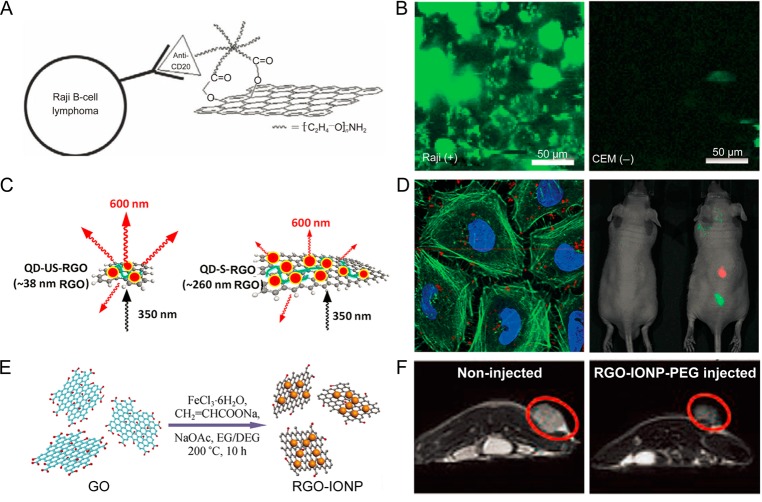

Optical imaging is an inexpensive, widely available, and highly sensitive imaging technique.84−86 By using the intrinsic photoluminescence of nGO in the near-infrared (NIR) range, nGO was functionalized with PEG and Rituxan anti-CD20 (a B-cell specific antibody) to form nGO-PEG-Rituxan and examined in the range of 1100–2200 nm (Figure 3A).47 Optical imaging demonstrated the specific uptake of nGO-PEG-Rituxan in Raji B-cell surfaces (CD20 positive), but not in CEM T-cells (CD20 negative) (Figure 3B). Due to the relatively low autofluorescence, excellent image contrast could be obtained.

Figure 3.

Functionalization of graphene for cancer imaging. (A) Schematic drawing illustrating nGO-PEG conjugated with anti-CD20 antibody Rituxan. (B) NIR fluorescence image of nGO-PEG-Rituxan conjugate in CD20 positive cells (left) and negative cells (right). (C) Schematic illustration of shielding effect of RGO for the two sizes, absorbing more incoming irradiation and stimulating less QD fluorescence by the larger RGO. (D) Optical imaging exhibiting locations of the QD-US-RGO within the cells (left) and mouse (right). (E) Schematic illustration of synthesis of RGO-IONP. (F) T2-weigted MR imaging of noninjected mouse (left) and injected mouse (right) with RGO-IONP-PEG. Reproduced with permission from refs (30, 34, 47, and 88).

Besides intrinsic photoluminescence, various fluorescent labels such as organic dyes18,74 and QDs28−30 have been functionalized on graphene for optical imaging. For example, a commonly used NIR fluorescent dye (i.e., Cy7) was conjugated to nGO-PEG for in vivo optical imaging in mice bearing different kinds of tumors (i.e., 4T1 murine breast cancer tumors, KB human epidermoid carcinoma tumors, and U87MG human glioblastoma tumors).18

Conjugating QDs (or other optical imaging nanoparticles)79 onto RGO could also result in fluorescent RGO provided that optical quenching is efficiently suppressed.28−30 For example, tri-n-octylphosphine oxide (TOPO) protected QDs were attached onto RGO-PLL, resulting in RGO-PLL-QD with effectively reduced fluorescence quenching.30 Interestingly, QD-loaded ultrasmall RGO sheets (i.e., QD-US-RGO) demonstrated a decreased fluorescence quenching when compared with QD-loaded larger RGO sheets (QD-S-RGO) (Figure 3C). The imaging property was tested in cells and mice (Figure 3D), demonstrating that both size and surface modification play important roles in the optical imaging of QD integrated graphene.

PET Imaging

PET is a highly sensitive and quantitative imaging modality and could become a useful imaging tool for studying the in vivo fate of graphene-based nanomaterial after radiolabeling.84,85,87 So far, radioisotopes such as copper-64 (64Cu, t1/2 = 12.7 h) have been labeled to GO (or RGO) for in vivo biodistribution and targeting studies.35,37,76,80 In one study, GO was modified with 2-(1-hexyloxyethyl)-2-devinyl pyropheophorbide-α (HPPH), which could bind to 64Cu for PET imaging via passive targeting.76 Higher tumor uptake was achieved with HPPH modified GO in comparison with HPPH alone, indicating the successful in vivo passive targeting. In another study, we reported the synthesis of 64Cu-labeled GO and RGO by using NOTA (i.e., 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid) as the chelator.35,37 For example, rapid and persistent tumor uptake was achieved with 64Cu-labeled GO and peaked at 3 h post injection (>5%ID/g) with excellent image contrast, suggesting the potential of graphene-based nanomaterials for PET imaging in preclinical studies and future applications.35 Since in vivo active targeting has been successfully achieved, this study will be discussed in detail in a later section.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) are well-studied T2 contrast agents, and have been decorated to GO or RGO using different strategies.23,24,34 In one study, IONPs were decorated onto GO via chemical deposition using soluble GO as carriers, where Fe3+/Fe2+ ions with a proper ratio were captured by carboxylate anions on the graphene sheet by coordination, forming IONPs on GO after treatment with NaOH solution at 65 °C.21 In follow-up study, a simple in situ method for decorating RGO with monodisperse IONPs was reported by reacting iron(III) acetylacetonate (Fe(acac)3) in liquid polyol triethylene glycol (TREG) at high temperature.22 The distribution of IONPs on the RGO sheet was found to be uniform with no obvious magnetic particle aggregation. Furthermore, in another interesting study, GO-IONP-PEG was synthesized by the reduction reaction between FeCl3 and diethylene glycol (DEG) in the presence of NaOH at high temperature and MRI with enhanced T2-weighted MR images was then achieved in mice, suggesting that integrated graphene could be an excellent platform for in vivo MRI (Figure 3E and F).34,88 Besides IONPs, gadolinium (Gd)-based complexes have also been conjugated to GO for enhanced T1-weighted MR imaging.82

Other Imaging Modalities

Functionalized GO has attracted extensive interest in photoacoustic (PA) imaging for noninvasive imaging of tissue structures and functions, due to its strong NIR light absorbance.89 It was proven that the PA signal (under a laser pulse of 808 nm) remained strong at a depth of 11 mm and gradually weakened as the detection depth increased in ex vivo studies.90 In vivo PA imaging has also been accomplished in mice model.34,91 Raman imaging is another application of graphene-based nanomaterials, due to the inherent Raman signals.92 It was discovered that the inherent Raman signals were significantly enhanced after integration of metal nanoparticles with graphene-based nanomaterials.93,94 The integrated nanoparticles (e.g., GO-Au or GO-Ag NPs) have been tested in living cells as sensitive optical probes.95−97 Besides, single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) has also been applied for tumor imaging with graphene-based nanomaterials.98 However, considering the higher sensitivity of PET over SPECT,99 most of current radiolabeled studies have been focused on PET imaging.

Photothermal Therapy and Photodynamic Therapy

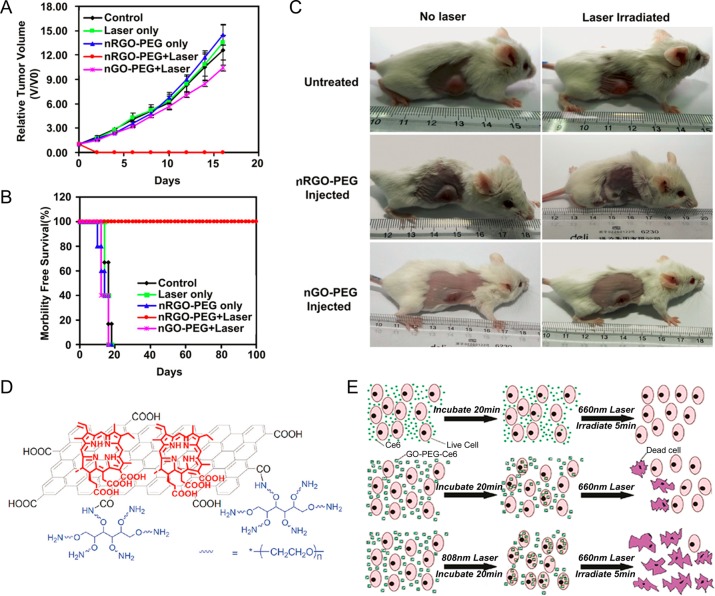

PEGylated GO (i.e., GO-PEG) is one of the first reported graphene derivatives designed for in vivo photothermal therapy (PTT), and showed highly efficient tumor ablation under NIR light irradiation (808 nm, 2 W/cm2).18 No obvious side effects of GO-PEG were noticed during the treatment. To further improve the PTT efficiency, in a follow-up study, RGO with a more restored graphene structure was utilized by the same group.31 PEGylated ultrasmall nRGO (i.e., nRGO-PEG) with an average size of 27 nm was prepared. Systematic in vivo PTT study demonstrated highly efficient tumor ablation under significantly reduced NIR laser power density (0.15 W/cm2) and improved survival (Figure 4A,B,C), indicating RGO could be one of the best candidates for PTT with a low-power laser irradiation. Besides pure GO, nanoparticle-decorated GO has also been reported for synergistic enhanced PTT. For example, gold nanoparticles (or nanorods) were attached onto GO resulting in enhanced PTT effects.25,26 Other nanoparticles such as silver (Ag),100 copper(I) oxide (Cu2O),101 and copper monosulfide (CuS)102 have also been integrated with GO for similarly enhanced PTT.

Figure 4.

Photothermal therapy and photodynamic therapy with functionalized graphene. (A) Tumor growth curves of different groups of mice after treatment. The tumor volumes were normalized to their initial sizes. (B) Survival curves of mice bearing 4T1 tumors after various treatments indicated. nRGO-PEG injected mice after PTT treatment survived over 100 days without a single death. (C) Representative photos of tumor-bearing mice after various treatments indicated. The laser irradiated tumors on the nRGO-PEG injected mice were completely destructed. Laser wavelength = 808 nm. Power density = 0.15 W/cm2. Irradiation time = 5 min. (D) Schematic illustration showing Ce6 loading on GO-PEG. Red: Ce6; black: GO; blue: six-arm PEG. (E) Schemes of the experimental design in photothermally enhanced photodynamic therapy. Free Ce6 (top) and GO-PEG-Ce6 (middle) for 20 min in the dark and then irradiated by the 660 nm laser (50 mW/cm2, 5 min, 15 J/cm2) for PDT in control experiments; GO-PEG-Ce6 incubated cells were exposed to the 808 nm laser (0.3 W/cm2, 20 min, 360 J/cm2) first (bottom) to induce PTT before PDT treatment. Reproduced with permission from refs (31 and 105).

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is another recognized alternative for the treatment of various cancers by triggering the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through the interaction of light with selected photosensitizers (PSs).103 PSs such as zinc phthalocyanine (ZnPc), Chlorin e6 (Ce6), and others have been loaded on the surface of GO-PEG for PDT studies in vitro and in vivo.32,104 For example, research showed that Chlorin e6 (Ce6) could be attached to the surface of GO via hydrophobic interactions and π–π stacking.32 As-synthesized GO-Ce6 nanosheets showed increased accumulation of Ce6 in tumor cells and could lead to a remarkable photodynamic efficacy upon light irradiation (633 nm). A PTT/PDT combined therapy could also be achieved by using GO-PEG-Ce6 (Figure 4D).105 Significantly enhanced therapeutic outcome was observed when compared with either PDT or PTT alone (Figure 4E), highlighting the attractive potential of combined phototherapy using graphene-based nanomaterials.

Drug and Gene Delivery

Graphene-based nanomaterials can also be used for drug and gene delivery.46,106 The strong π–π interaction allows for the loading of various aromatic drug molecules such as doxorubicin (DOX)13,20,47,107 and camptothecin (CPT),13,57,108 while hydrophobic interaction provides a chance to bind to numerous poorly water-soluble drugs, such as paclitaxel, without compromising their potency or efficiency.109 By appropriate surface coating with PEI or chitosan, as functionalized graphene could also be used for effective gene delivery.8,46,110

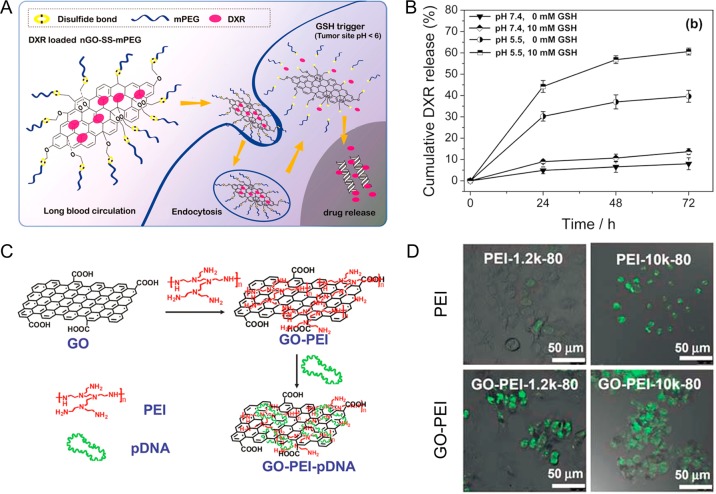

DOX was loaded on to nGO-PEG by simply mixing the two together at pH 8 environment via π–π stacking to form nGO-PEG-DOX.47 A similar loading mechanism was used for the synthesis of nGO-PEG-SN38 (SN38 is an analogue of CPT).10 The resulting nGO-PEG-SN38 complex exhibited excellent water solubility while maintaining a high chemotherapeutic potency similar to that of the free SN38 molecules. In addition to single drug loading, nGO can be used for loading multiple drugs for chemotherapy. For example, both DOX and CPT were loaded on functionalized nGO and showed higher cytotoxicity to cancer cells compared to nGO loaded with DOX or CPT alone.13 More sophisticated surface engineering techniques have also been reported for achieving on-demand drug release functionality. For example, disulfide linkages were introduced to PEGylated GO to form nGO-SS-mPEG (mPEG = methoxy polyethylene glycol) (Figure 5A).107 PEG was able to selectively detach from nGO upon intracellular glutathione (GSH) stimulation and effectively accelerate the drug release at lower pH (Figure 5B). In a recent study, GO was modified with 2,3-dimethylmaleic anhydride (DA), which is negatively charged under physiological pH at 7.4 and could be rapidly converted into positively charged moiety in a slightly acidic environment (pH 6.8).111 Significantly enhanced pH-responsive drug release and improved therapeutic efficacy were achieved in cells. Overall, these studies demonstrated the potential of using graphene-based nanomaterials for loading and delivery of aromatic and/or hydrophobic drugs.

Figure 5.

Functionalization of GO for drug and gene delivery. (A) Schematic diagram showing antitumor activity of redox-sensitive Doxorubicin (DXR)-loaded nGO-SS-mPEG. (B) GSH-mediated drug release from DXR-loaded nGO-SS-mPEG at pH 7.4 and 5.5. Higher release rate was achieved in the presence of GSH at pH 5.5. (C) Schematic illustration showing the synthesis of GO-PEI conjugate and the preparation of GO-PEI-pDNA complex. (D) Confocal images of PEI and GO-PEI transfected HeLa cells with two different molecular weights of PEI (N/P ratio = 80). Reproduced with permission from refs (9 and 107).

The development of nanoparticle-based gene delivery is still limited by the immunogenicity and potential cytotoxicity of gene carriers.112,113 Successful loading and intracellular transfection of plasmid DNA (pDNA) in HeLa cells has been reported recently by using PEI functionalized GO (Figure 5C).9 Results showed that the chain length of PEI could have a significant influence on the transfection rate and cellular toxicity. GO-PEI-1.2k exhibited higher transfection efficiency than PEI-1.2k, while GO-PEI-10k exhibited lower cellular toxicity than PEI-10k (Figure 5D). This work demonstrated that GO could potentially become an effective platform for further applications in nonviral gene therapy. In addition, under irradiation with NIR light beam, enhanced cellular uptake was achieved due to mild photothermal heating, which increased the cell membrane permeability.110 Besides pDNA, small interfering RNA (siRNA) was also delivered with nGO-PEG-PEI.15,110

In Vivo Tumor Targeting with Graphene-Based Nanomaterials

Although graphene-based nanomaterials have shown attractive potential for future cancer imaging and therapy, it is still a major challenge to improve their in vivo tumor targeting efficiency.114−117 In comparison with passive and tumor cell-based targeting strategies, tumor angiogenesis targeting (or vasculature targeting) has recently been accepted as a generally applicable in vivo targeting strategy for most nanoparticles regardless of tumor types.118

CD105, also known as endoglin, is an ideal marker for tumor angiogenesis since it is almost exclusively expressed on proliferating endothelial cells.119 Recently, by using TRC105 (a human/murine chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to both human and murine CD105),120,121 we reported the first example of in vivo active targeted PET imaging of well-designed GO and RGO nanoconjugates (Figure 6A).35−37 Significantly higher uptake in 4T1 murine breast tumors (which express high level of CD105 on the tumor vasculature) was observed for TRC105-conjugated GO, which was about 2-fold that for the nontargeted GO (Figure 6B). Enhanced tumor uptake with high specificity and little extravasation was achieved in this study, encouraging future investigation of these GO conjugates for cancer-targeted drug delivery and/or PTT to enhance therapeutic efficacy.

Figure 6.

Conjugation of targeting ligands for tumor active targeting. (A) Schematic representation of the nanographene conjugates with NOTA as the chelator for in vivo imaging and TRC105 as the targeting ligand. (B) Coronal PET images of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice at 3 h postinjection of 64Cu-NOTA-GO-TRC105 (targeted), 64Cu-NOTA-GO (nontargeted), or 64Cu-NOTA-GO-TRC105 after a preinjected blocking dose of TRC105 (blocking). Enhanced tumor uptake was achieved with 64Cu-NOTA-GO-TRC105 compared with nontargeting and blocking groups. Reproduced with permission from ref (35).

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Over the past decade, great efforts have been made to employ functionalized graphene-based nanomaterials in biomedical applications. Optical imaging has been widely studied via either intrinsic fluorescence of graphene or integrating fluorescent dyes and nanoparticles. Although optical imaging is limited by limited tissue penetration and quenching from graphene, the undesired quenching could possibly be utilized for engineering of activatable fluorescent probes for on-demand imaging with enhanced contrast. Compared with optical imaging, PET and MRI could become better candidates for future in vivo imaging due to their excellent tissue penetration property. For therapy, PTT, PDT, and drug (or gene) delivery have proven to be efficient and effective methods with reduced side effects to normal tissues, where the surface engineering plays an important role in the therapeutic efficacy. With sophisticated surface engineering, graphene-based nanomaterials could be designed as multifunctional probes for multimodality image-guided therapy, which would be one of the most promising research directions in the next 5 years.

Despite recent progress in surface engineering of graphene-based nanomaterials for biomedical applications, challenges still exist. Among them, potential long-term toxicity and unsatisfactory tumor targeting efficacy are two of the major concerns. As discussed, surface functionalization plays a critical role in improving the solubility and biocompatibility of graphene-based nanomaterials. By modification with various biocompatible molecules, significantly improved stability and reduced toxicity have been achieved. Although PEGylation has been accepted as the best surface modification method, due to the relatively large size and nonbiodegradable property of graphene-based nanomaterials, the high liver uptake and potential long-term toxicity are still major concerns for future clinical translation. Second, although enhanced GO (or RGO) accumulation has been demonstrated with the assistance of well-selected antibodies, so far the tumor targeting efficacy is still relatively low (5–8%ID/g). The development of new tumor targeting strategies, better tumor targeting ligands and bioconjugation techniques will be highly useful for the engineering of the next generation of graphene-based nanomaterials.

In conclusion, we summarized the functionalization of graphene-based nanomaterials for various biomedical applications. With appropriate surface engineering techniques, graphene and its derivatives could be used for cancer multimodality imaging, photothermal therapy, photodynamic therapy, drug and gene delivery, cancer active targeting, and other applications.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported, in part, by the University of Wisconsin - Madison, the National Institutes of Health (NIBIB/NCI 1R01CA169365), the Department of Defense (W81XWH-11-1-0644), and the American Cancer Society (125246-RSG-13-099-01-CCE).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Novoselov K. S.; Geim A. K.; Morozov S. V.; Jiang D.; Zhang Y.; Dubonos S. V.; Grigorieva I. V.; Firsov A. A. (2004) Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geim A. K.; Novoselov K. S. (2007) The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.; Yin Z.; Wu S.; Qi X.; He Q.; Zhang Q.; Yan Q.; Boey F.; Zhang H. (2011) Graphene-based materials: synthesis, characterization, properties, and applications. Small 7, 1876–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Wang X.; Zhang L.; Lee S.; Dai H. (2008) Chemically derived, ultrasmooth graphene nanoribbon semiconductors. Science 319, 1229–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumera M. (2010) Graphene-based nanomaterials and their electrochemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 4146–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Service R. F. (2009) Materials science. Carbon sheets an atom thick give rise to graphene dreams. Science 324, 875–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Nayak T. R.; Hong H.; Cai W. (2012) Graphene: a versatile nanoplatform for biomedical applications. Nanoscale 4, 3833–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K.; Feng L.; Shi X.; Liu Z. (2013) Nano-graphene in biomedicine: theranostic applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 530–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L.; Zhang S.; Liu Z. (2011) Graphene based gene transfection. Nanoscale 3, 1252–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Robinson J. T.; Sun X.; Dai H. (2008) PEGylated nanographene oxide for delivery of water-insoluble cancer drugs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 10876–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Lee D.; Kim J.; Kim T. I.; Kim W. J. (2013) Photothermally triggered cytosolic drug delivery via endosome disruption using a functionalized reduced graphene oxide. ACS Nano 7, 6735–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao W.; Shim G.; Kang C. M.; Lee S.; Choe Y. S.; Choi H. G.; Oh Y. K. (2013) Cholesteryl hyaluronic acid-coated, reduced graphene oxide nanosheets for anti-cancer drug delivery. Biomaterials 34, 9638–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Xia J.; Zhao Q.; Liu L.; Zhang Z. (2010) Functional graphene oxide as a nanocarrier for controlled loading and targeted delivery of mixed anticancer drugs. Small 6, 537–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L. A.; Wang J.; Loh K. P. (2010) Graphene-based SELDI probe with ultrahigh extraction and sensitivity for DNA oligomer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 10976–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Lu Z.; Zhao Q.; Huang J.; Shen H.; Zhang Z. (2011) Enhanced chemotherapy efficacy by sequential delivery of siRNA and anticancer drugs using PEI-grafted graphene oxide. Small 7, 460–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S.; Song B.; Li D.; Zhu C.; Qi W.; Wen Y.; Wang L.; Song S.; Fang H.; Fan C. (2010) A graphene nanoprobe for rapid, sensitive, and multicolor fluorescent DNA analysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Yang K.; Feng L.; Hong H.; Cai W.; Liu Z. (2013) Preparation and functionalization of graphene nanocomposites for biomedical applications. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K.; Zhang S.; Zhang G.; Sun X.; Lee S. T.; Liu Z. (2010) Graphene in mice: ultrahigh in vivo tumor uptake and efficient photothermal therapy. Nano Lett. 10, 3318–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K.; Wan J.; Zhang S.; Zhang Y.; Lee S. T.; Liu Z. (2011) In vivo pharmacokinetics, long-term biodistribution, and toxicology of PEGylated graphene in mice. ACS Nano 5, 516–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Guo Z. Y.; Huang D. Q.; Liu Z. M.; Guo X.; Zhong H. Q. (2011) Synergistic effect of chemo-photothermal therapy using PEGylated graphene oxide. Biomaterials 32, 8555–8561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. Y.; Zhang X. Y.; Ma Y. F.; Huang Y.; Wang Y. S.; Chen Y. S. (2009) Superparamagnetic graphene oxide-Fe3O4 nanoparticles hybrid for controlled targeted drug carriers. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 2710–2714. [Google Scholar]

- Cong H. P.; He J. J.; Lu Y.; Yu S. H. (2010) Water-soluble magnetic-functionalized reduced graphene oxide sheets: in situ synthesis and magnetic resonance imaging applications. Small 6, 169–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H.; Gao C. (2010) Supraparamagnetic, conductive, and processable multifunctional graphene nanosheets coated with high-density Fe3O4 nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2, 3201–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F. A.; Fan J. T.; Ma D.; Zhang L. M.; Leung C.; Chan H. L. (2010) The attachment of Fe3O4 nanoparticles to graphene oxide by covalent bonding. Carbon 48, 3139–3144. [Google Scholar]

- Zedan A. F.; Moussa S.; Terner J.; Atkinson G.; El-Shall M. S. (2013) Ultrasmall gold nanoparticles anchored to graphene and enhanced photothermal effects by laser irradiation of gold nanostructures in graphene oxide solutions. ACS Nano 7, 627–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembereldorj U.; Choi S. Y.; Ganbold E. O.; Song N. W.; Kim D.; Choo J.; Lee S. Y.; Kim S.; Joo S. W. (2014) Gold nanorod-assembled PEGylated graphene-oxide nanocomposites for photothermal cancer therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 90, 659–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.; Wang J.; Ke H.; Wang S.; Dai Z. (2013) Graphene oxide modified PLA microcapsules containing gold nanoparticles for ultrasonic/CT bimodal imaging guided photothermal tumor therapy. Biomaterials 34, 4794–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. L.; Liu J. W.; Hu B.; Wang J. H. (2011) Conjugation of quantum dots with graphene for fluorescence imaging of live cells. Analyst 136, 4277–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. L.; He Y. J.; Chen X. W.; Wang J. H. (2013) Quantum-dot-conjugated graphene as a probe for simultaneous cancer-targeted fluorescent imaging, tracking, and monitoring drug delivery. Bioconjugate Chem. 24, 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S. H.; Chen Y. W.; Hung W. T.; Chen I. W.; Chen S. Y. (2012) Quantum-dot-tagged reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites for bright fluorescence bioimaging and photothermal therapy monitored in situ. Adv. Mater. 24, 1748–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K.; Wan J.; Zhang S.; Tian B.; Zhang Y.; Liu Z. (2012) The influence of surface chemistry and size of nanoscale graphene oxide on photothermal therapy of cancer using ultra-low laser power. Biomaterials 33, 2206–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P.; Xu C.; Lin J.; Wang C.; Wang X.; Zhang C.; Zhou X.; Guo S.; Cui D. (2011) Folic acid-conjugated graphene oxide loaded with photosensitizers for targeting photodynamic therapy. Theranostics 1, 240–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L.; Wang W.; Tang J.; Zhou J. H.; Jiang H. J.; Shen J. (2011) Graphene oxide noncovalent photosensitizer and its anticancer activity in vitro. Chemistry 17, 12084–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K.; Hu L.; Ma X.; Ye S.; Cheng L.; Shi X.; Li C.; Li Y.; Liu Z. (2012) Multimodal imaging guided photothermal therapy using functionalized graphene nanosheets anchored with magnetic nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 24, 1868–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H.; Yang K.; Zhang Y.; Engle J. W.; Feng L.; Yang Y.; Nayak T. R.; Goel S.; Bean J.; Theuer C. P.; Barnhart T. E.; Liu Z.; Cai W. (2012) In vivo targeting and imaging of tumor vasculature with radiolabeled, antibody-conjugated nanographene. ACS Nano 6, 2361–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H.; Zhang Y.; Engle J. W.; Nayak T. R.; Theuer C. P.; Nickles R. J.; Barnhart T. E.; Cai W. (2012) In vivo targeting and positron emission tomography imaging of tumor vasculature with (66)Ga-labeled nano-graphene. Biomaterials 33, 4147–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S.; Yang K.; Hong H.; Valdovinos H. F.; Nayak T. R.; Zhang Y.; Theuer C. P.; Barnhart T. E.; Liu Z.; Cai W. (2013) Tumor vasculature targeting and imaging in living mice with reduced graphene oxide. Biomaterials 34, 3002–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eda G.; Chhowalla M. (2010) Chemically derived graphene oxide: towards large-area thin-film electronics and optoelectronics. Adv. Mater. 22, 2392–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X.; Zhang C.; Hao R.; Hou Y. (2011) Liquid-phase exfoliation, functionalization and applications of graphene. Nanoscale 3, 2118–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer D. R.; Park S.; Bielawski C. W.; Ruoff R. S. (2010) The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 228–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Ruoff R. S. (2009) Chemical methods for the production of graphenes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C. H.; Nesladek M.; Loh K. P. (2014) Observing high-pressure chemistry in graphene bubbles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A. M.; Derby B.; Kinloch I. A. (2013) Influence of gas phase equilibria on the chemical vapor deposition of graphene. ACS Nano 7, 3104–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummers W. S.; Offeman R. E. (1958) Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 1339–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Pei S. F.; Cheng H. M. (2012) The reduction of graphene oxide. Carbon 50, 3210–3228. [Google Scholar]

- Goenka S.; Sant V.; Sant S. (2014) Graphene-based nanomaterials for drug delivery and tissue engineering. J. Controlled Release 173, 75–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Liu Z.; Welsher K.; Robinson J. T.; Goodwin A.; Zaric S.; Dai H. (2008) Nano-graphene oxide for cellular imaging and drug delivery. Nano Res. 1, 203–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtoniszak M.; Chen X.; Kalenczuk R. J.; Wajda A.; Lapczuk J.; Kurzewski M.; Drozdzik M.; Chu P. K.; Borowiak-Palen E. (2012) Synthesis, dispersion, and cytocompatibility of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide. Colloids Surf., B 89, 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K.; Gong H.; Shi X.; Wan J.; Zhang Y.; Liu Z. (2013) In vivo biodistribution and toxicology of functionalized nano-graphene oxide in mice after oral and intraperitoneal administration. Biomaterials 34, 2787–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X.; Feng L.; Zhang J.; Yang K.; Zhang S.; Liu Z.; Peng R. (2013) Functionalization of graphene oxide generates a unique interface for selective serum protein interactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q.; Zhao Y.; Fang J.; Wang D. (2014) Immune response is required for the control of in vivo translocation and chronic toxicity of graphene oxide. Nanoscale 6, 5894–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Feng L.; Shi X.; Wang X.; Yang Y.; Yang K.; Liu T.; Yang G.; Liu Z. (2014) Surface coating-dependent cytotoxicity and degradation of graphene derivatives: towards the design of non-toxic, degradable nano-graphene. Small 10, 1544–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan C.; Yang H.; Han D.; Zhang Q.; Ivaska A.; Niu L. (2009) Water-soluble graphene covalently functionalized by biocompatible poly-L-lysine. Langmuir 25, 12030–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollavelli G.; Ling Y. C. (2012) Multi-functional graphene as an in vitro and in vivo imaging probe. Biomaterials 33, 2532–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. A.; Yang K.; Feng L. Z.; Liu Z. (2011) In vitro and in vivo behaviors of dextran functionalized graphene. Carbon 49, 4040–4049. [Google Scholar]

- Jin R.; Ji X.; Yang Y.; Wang H.; Cao A. (2013) Self-assembled graphene-dextran nanohybrid for killing drug-resistant cancer cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 7181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao H. Q.; Pan Y. Z.; Ping Y.; Sahoo N. G.; Wu T. F.; Li L.; Li J.; Gan L. H. (2011) Chitosan-functionalized graphene oxide as a nanocarrier for drug and gene delivery. Small 7, 1569–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Mallela J.; Garapati U. S.; Ravi S.; Chinnasamy V.; Girard Y.; Howell M.; Mohapatra S. (2013) A chitosan-modified graphene nanogel for noninvasive controlled drug release. Nanomedicine 9, 903–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. H.; Zhou C. F.; Xia J. F.; Via B.; Xia Y. Z.; Zhang F. F.; Li Y. H.; Xia L. H. (2013) Fabrication and characterization of a triple functionalization of graphene oxide with Fe3O4, folic acid and doxorubicin as dual-targeted drug nanocarrier. Colloids Surf., B 106, 60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depan D.; Shah J.; Misra R. D. K. (2011) Controlled release of drug from folate-decorated and graphene mediated drug delivery system: Synthesis, loading efficiency, and drug release response. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 31, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. T.; Tabakman S. M.; Liang Y.; Wang H.; Casalongue H. S.; Vinh D.; Dai H. (2011) Ultrasmall reduced graphene oxide with high near-infrared absorbance for photothermal therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. T.; Welsher K.; Tabakman S. M.; Sherlock S. P.; Wang H.; Luong R.; Dai H. (2010) High performance in vivo near-IR (>1 mum) imaging and photothermal cancer therapy with carbon nanotubes. Nano Res. 3, 779–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prencipe G.; Tabakman S. M.; Welsher K.; Liu Z.; Goodwin A. P.; Zhang L.; Henry J.; Dai H. (2009) PEG branched polymer for functionalization of nanomaterials with ultralong blood circulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 4783–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Mohanty N.; Suk J. W.; Nagaraja A.; An J.; Piner R. D.; Cai W.; Dreyer D. R.; Berry V.; Ruoff R. S. (2010) Biocompatible, robust free-standing paper composed of a TWEEN/graphene composite. Adv. Mater. 22, 1736–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H.; Yu J.; Li Y.; Zhao J.; Dong H. (2012) Engineering of a novel pluronic F127/graphene nanohybrid for pH responsive drug delivery. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A 100, 141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q. Y.; Han B. H. (2013) Supramolecular hydrogel based on graphene oxides for controlled release system. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 13, 755–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James M. L.; Gambhir S. S. (2012) A molecular imaging primer: modalities, imaging agents, and applications. Physiol. Rev. 92, 897–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Wu Y.; Wang F.; Liu Z. (2014) Molecular imaging of integrin alphavbeta6 expression in living subjects. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 4, 333–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolting D. D.; Nickels M. L.; Guo N.; Pham W. (2012) Molecular imaging probe development: a chemistry perspective. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2, 273–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wate P. S.; Banerjee S. S.; Jalota-Badhwar A.; Mascarenhas R. R.; Zope K. R.; Khandare J.; Misra R. D. K. (2012) Cellular imaging using biocompatible dendrimer-functionalized graphene oxide-based fluorescent probe anchored with magnetic nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 23, 415101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H.; Li Y.; Yu J.; Song Y.; Cai X.; Liu J.; Zhang J.; Ewing R. C.; Shi D. (2013) A versatile multicomponent assembly via beta-cyclodextrin host-guest chemistry on graphene for biomedical applications. Small 9, 446–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurunnabi M.; Khatun Z.; Reeck G. R.; Lee D. Y.; Lee Y. K. (2013) Near infra-red photoluminescent graphene nanoparticles greatly expand their use in noninvasive biomedical imaging. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 49, 5079–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurunnabi M.; Khatun Z.; Nafiujjaman M.; Lee D. G.; Lee Y. K. (2013) Surface coating of graphene quantum dots using mussel-inspired polydopamine for biomedical optical imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 8246–8253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D.; Song Y. C.; Shi W.; Li X. H.; Ma H. M. (2013) Distinguishing folate-receptor-positive cells from folate-receptor-negative cells using a fluorescence off-on nanoprobe. Anal. Chem. 85, 6530–6535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y.; Zou X.; Zhao J. X.; Li Y.; Su X. (2013) Graphene oxide-based magnetic fluorescent hybrids for drug delivery and cellular imaging. Colloids Surf., B 112, 128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong P.; Yang K.; Srivastan A.; Kiesewetter D. O.; Yue X.; Wang F.; Nie L.; Bhirde A.; Wang Z.; Liu Z.; Niu G.; Wang W.; Chen X. (2014) Photosensitizer loaded nano-graphene for multimodality imaging guided tumor photodynamic therapy. Theranostics 4, 229–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosuge H.; Sherlock S. P.; Kitagawa T.; Terashima M.; Barral J. K.; Nishimura D. G.; Dai H.; McConnell M. V. (2011) FeCo/graphite nanocrystals for multi-modality imaging of experimental vascular inflammation. PLoS One 6, e14523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Tian F.; Wang W. X.; Chen J.; Wu M.; Zhao J. X. (2013) Fabrication of highly fluorescent graphene quantum dots using L-glutamic acid for in vitro/in vivo imaging and sensing. J. Mater. Chem. C 1, 4676–4684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Wang H.; Liu D.; Song S.; Wang X.; Zhang H. (2013) Graphene oxide covalently grafted upconversion nanoparticles for combined NIR mediated imaging and photothermal/photodynamic cancer therapy. Biomaterials 34, 7715–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.; Huang P.; Tong G.; Lin J.; Jin A.; Rong P.; Zhu L.; Nie L.; Niu G.; Cao F.; Chen X. (2013) VEGF-loaded graphene oxide as theranostics for multi-modality imaging-monitored targeting therapeutic angiogenesis of ischemic muscle. Nanoscale 5, 6857–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Aburto R.; Narayanan T. N.; Nagaoka Y.; Hasumura T.; Mitcham T. M.; Fukuda T.; Cox P. J.; Bouchard R. R.; Maekawa T.; Kumar D. S.; Torti S. V.; Mani S. A.; Ajayan P. M. (2013) Fluorinated graphene oxide; a new multimodal material for biological applications. Adv. Mater. 25, 5632–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Cao Y.; Chong Y.; Ma Y.; Zhang H.; Deng Z.; Hu C.; Zhang Z. (2013) Graphene oxide based theranostic platform for T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and drug delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 13325–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gizzatov A.; Keshishian V.; Guven A.; Dimiev A. M.; Qu F.; Muthupillai R.; Decuzzi P.; Bryant R. G.; Tour J. M.; Wilson L. J. (2014) Enhanced MRI relaxivity of aquated Gd3+ ions by carboxyphenylated water-dispersed graphene nanoribbons. Nanoscale 6, 3059–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W.; Chen X. (2007) Nanoplatforms for targeted molecular imaging in living subjects. Small 3, 1840–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoud T. F.; Gambhir S. S. (2003) Molecular imaging in living subjects: seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes Dev. 17, 545–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X.; Lee S.; Chen X. (2011) Design of ″smart″ probes for optical imaging of apoptosis. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 1, 3–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopci E.; Grassi I.; Chiti A.; Nanni C.; Cicoria G.; Toschi L.; Fonti C.; Lodi F.; Mattioli S.; Fanti S. (2014) PET radiopharmaceuticals for imaging of tumor hypoxia: a review of the evidence. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 4, 365–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H.; Cao L.; Lu L. (2011) Magnetite/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites: One step solvothermal synthesis and use as a novel platform for removal of dye pollutants. Nano Res. 4, 550–562. [Google Scholar]

- Patel M. A.; Yang H.; Chiu P. L.; Mastrogiovanni D. D.; Flach C. R.; Savaram K.; Gomez L.; Hemnarine A.; Mendelsohn R.; Garfunkel E.; Jiang H.; He H. (2013) Direct production of graphene nanosheets for near infrared photoacoustic imaging. ACS Nano 7, 8147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.-D.; Liang X.-L.; Yue X.-L.; Wang J.-R.; Li C.-H.; Deng Z.-J.; Jing L.-J.; Lin L.; Qu E.-Z.; Wang S.-M.; Wu C.-L.; Wu H.-X.; Dai Z.-F. (2014) Imaging guided photothermal therapy using iron oxide loaded poly(lactic acid) microcapsules coated with graphene oxide. J. Mater. Chem. B 2, 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng Z.; Song L.; Zheng J.; Hu D.; He M.; Zheng M.; Gao G.; Gong P.; Zhang P.; Ma Y.; Cai L. (2013) Protein-assisted fabrication of nano-reduced graphene oxide for combined in vivo photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy. Biomaterials 34, 5236–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X.; Bei F.; Wang X.; O’Brien S.; Lombardi J. R. (2010) Excitation profile of surface-enhanced Raman scattering in graphene-metal nanoparticle based derivatives. Nanoscale 2, 1461–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.; Wang X. (2009) Fabrication of flexible metal-nanoparticle films using graphene oxide sheets as substrates. Small 5, 2212–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. K.; Na H. K.; Lee Y. W.; Jang H.; Han S. W.; Min D. H. (2010) The direct growth of gold rods on graphene thin films. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 46, 3185–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Wei L.; Wang J.; Peng F.; Luo D.; Cui R.; Niu Y.; Qin X.; Liu Y.; Sun H.; Yang J.; Li Y. (2012) Cell imaging by graphene oxide based on surface enhanced Raman scattering. Nanoscale 4, 7084–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X.; Qu Q.; Zhao Y.; Luo Z.; Zhao Y.; Ng K. W.; Zhao Y. (2013) Graphene oxide wrapped gold nanoparticles for intracellular Raman imaging and drug delivery. J. Mater. Chem. B 1, 6495–6500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Guo Z.; Zhong H.; Qin X.; Wan M.; Yang B. (2013) Graphene oxide based surface-enhanced Raman scattering probes for cancer cell imaging. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 2961–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen B.; Able S.; Kersemans V.; Waghorn P. A.; Myhra S.; Jurkshat K.; Crossley A.; Vallis K. A. (2013) Nanographene oxide-based radioimmunoconstructs for in vivo targeting and SPECT imaging of HER2-positive tumors. Biomaterials 34, 1146–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmim A.; Zaidi H. (2008) PET versus SPECT: strengths, limitations and challenges. Nucl. Med. Commun. 29, 193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.; Wang L.; Zhang J.; Ma R.; Gao J.; Liu Y.; Zhang C.; Zhang Z. (2014) A tumor-targeting near-infrared laser-triggered drug delivery system based on GO@Ag nanoparticles for chemo-photothermal therapy and X-ray imaging. Biomaterials 35, 5847–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou C. Y.; Quan H. C.; Duan Y. R.; Zhang Q. H.; Wang H. Z.; Li Y. G. (2013) Facile synthesis of water-dispersible Cu2O nanocrystal-reduced graphene oxide hybrid as a promising cancer therapeutic agent. Nanoscale 5, 1227–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J.; Liu Y.; Jiang X. (2014) Multifunctional PEG-GO/CuS nanocomposites for near-infrared chemo-photothermal therapy. Biomaterials 35, 5805–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmans D. E.; Fukumura D.; Jain R. K. (2003) Photodynamic therapy for cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 3, 380–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H. Q.; Zhao Z. L.; Wen H. Y.; Li Y. Y.; Guo F. F.; Shen A. J.; Frank P.; Lin C.; Shi D. L. (2010) Poly(ethylene glycol) conjugated nano-graphene oxide for photodynamic therapy. Sci. China: Chem. 53, 2265–2271. [Google Scholar]

- Tian B.; Wang C.; Zhang S.; Feng L.; Liu Z. (2011) Photothermally enhanced photodynamic therapy delivered by nano-graphene oxide. ACS Nano 5, 7000–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L.; Liu Z. (2011) Graphene in biomedicine: opportunities and challenges. Nanomedicine (London) 6, 317–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H.; Dong C.; Dong H.; Shen A.; Xia W.; Cai X.; Song Y.; Li X.; Li Y.; Shi D. (2012) Engineered redox-responsive PEG detachment mechanism in PEGylated nano-graphene oxide for intracellular drug delivery. Small 8, 760–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo N. G.; Bao H. Q.; Pan Y. Z.; Pal M.; Kakran M.; Cheng H. K. F.; Li L.; Tan L. P. (2011) Functionalized carbon nanomaterials as nanocarriers for loading and delivery of a poorly water-soluble anticancer drug: a comparative study. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 47, 5235–5237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya N.; Arora A.; Vasu K. S.; Sood A. K.; Katti D. S. (2013) Combination of single walled carbon nanotubes/graphene oxide with paclitaxel: a reactive oxygen species mediated synergism for treatment of lung cancer. Nanoscale 5, 2818–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L.; Yang X.; Shi X.; Tan X.; Peng R.; Wang J.; Liu Z. (2013) Polyethylene glycol and polyethylenimine dual-functionalized nano-graphene oxide for photothermally enhanced gene delivery. Small 9, 1989–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Li K., Shi X., Gao M., Liu J., ans Liu Z. (2014) Smart pH-responsive nanocarrier based on nano-graphene oxide for combined chemo- and photothermal therapy overcoming drug resistance. Advanced Healthcare Materials [Online early access] DOI: 10.1002/adhm.201300549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead K. A.; Langer R.; Anderson D. G. (2009) Knocking down barriers: advances in siRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discovery 8, 129–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. D.; Huang L. (2006) Gene therapy progress and prospects: non-viral gene therapy by systemic delivery. Gene Ther. 13, 1313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W.; Chen K.; Li Z. B.; Gambhir S. S.; Chen X. (2007) Dual-function probe for PET and near-infrared fluorescence imaging of tumor vasculature. J. Nucl. Med. 48, 1862–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W.; Chen X. (2008) Multimodality molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis. J. Nucl. Med. 49(Suppl 2), 113S–28S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W.; Shin D. W.; Chen K.; Gheysens O.; Cao Q.; Wang S. X.; Gambhir S. S.; Chen X. (2006) Peptide-labeled near-infrared quantum dots for imaging tumor vasculature in living subjects. Nano Lett. 6, 669–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W. B.; Chen X. Y. (2008) Preparation of peptide-conjugated quantum dots for tumor vasculature-targeted imaging. Nat. Protoc. 3, 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F.; Cai W. (2014) Tumor vasculature targeting: a generally applicable approach for functionalized nanomaterials. Small 10, 1887–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seon B. K.; Haba A.; Matsuno F.; Takahashi N.; Tsujie M.; She X.; Harada N.; Uneda S.; Tsujie T.; Toi H.; Tsai H.; Haruta Y. (2011) Endoglin-targeted cancer therapy. Curr. Drug Delivery 8, 135–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen L. S.; Hurwitz H. I.; Wong M. K.; Goldman J.; Mendelson D. S.; Figg W. D.; Spencer S.; Adams B. J.; Alvarez D.; Seon B. K.; Theuer C. P.; Leigh B. R.; Gordon M. S. (2012) A phase I first-in-human study of TRC105 (Anti-Endoglin Antibody) in patients with advanced cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 4820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orbay H.; Zhang Y.; Valdovinos H. F.; Song G.; Hernandez R.; Theuer C. P.; Hacker T. A.; Nickles R. J.; Cai W. (2013) Positron emission tomography imaging of CD105 expression in a rat myocardial infarction model with (64)Cu-NOTA-TRC105. Am. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 4, 1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]