Abstract

Objectives

Develop predictive models using an administrative healthcare database that provide information for Patient-Centred Medical Homes to proactively identify patients at risk of hospitalisation for conditions that may be impacted through improved patient care.

Design

Retrospective healthcare utilisation analysis with multivariate logistic regression models.

Data

A population-based longitudinal database of residents served by the Emilia-Romagna, Italy, health service in the years 2004–2012 including demographic information and utilisation of health services by 3 726 380 people aged ≥18 years.

Outcome measures

Models designed to predict risk of hospitalisation or death in 2012 for problems that are potentially avoidable were developed and evaluated using the area under the receiver operating curve C-statistic, in terms of their sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value, and for calibration to assess performance across levels of predicted risk.

Results

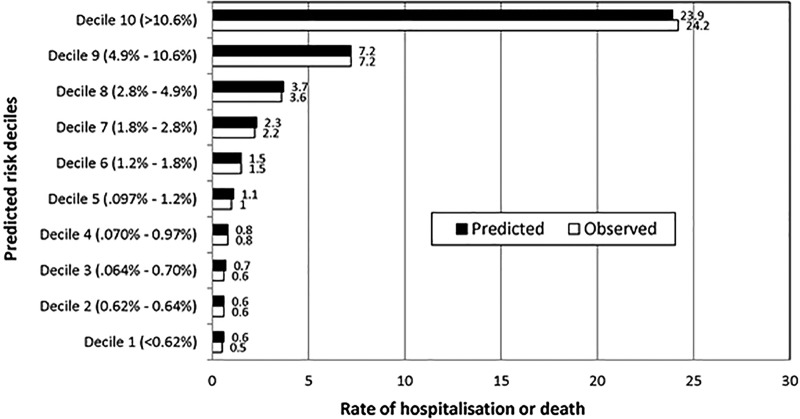

Among the 3 726 380 adult residents of Emilia-Romagna at the end of 2011, 449 163 (12.1%) were hospitalised in 2012; 4.2% were hospitalised for the selected conditions or died in 2012 (3.6% hospitalised, 1.3% died). The C-statistic for predicting 2012 outcomes was 0.856. The model was well calibrated across categories of predicted risk. For those patients in the highest predicted risk decile group, the average predicted risk was 23.9% and the actual prevalence of hospitalisation or death was 24.2%.

Conclusions

We have developed a population-based model using a longitudinal administrative database that identifies the risk of hospitalisation for residents of the Emilia-Romagna region with a level of performance as high as, or higher than, similar models. The results of this model, along with profiles of patients identified as high risk are being provided to the physicians and other healthcare professionals associated with the Patient Centred Medical Homes to aid in planning for care management and interventions that may reduce their patients’ likelihood of a preventable, high-cost hospitalisation.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study included the entire adult population of the Emilia-Romagna Region of Italy, over 3.7 million people.

The study used an existing longitudinal administrative healthcare database with both the advantage of much lower cost than new data collection and the disadvantage of potential errors in administrative data.

The results of the study are being used to assist in the development of newly formed Patient-Centred Medical Homes.

Introduction

The predominant healthcare delivery system, which has been a passive model, reacting to patients’ problems, is shifting to a more proactive model designed to take the initiative in providing care for an increasingly older population that has a greater prevalence of chronic conditions, often with multiple medical and social needs. These changes are driving the reorganisation of the primary care system, emphasising coordination and cooperation among healthcare professionals.1–3 Among the approaches to addressing this need has been the establishment of Patient-Centred Medical Homes, organisations in which teams of healthcare providers are engaged in delivering comprehensive, coordinated, patient-centred care to patient-defined populations.

Primary care has a central role in the Italian National Health Service (NHS). Twenty-one regional governments are responsible for ensuring the delivery of a health benefits package through a network of geographically defined, population-based Local Health Authorities. Primary care physicians work for these authorities as independent contractors and act as ‘gatekeepers’ for specialty and other referral services for their patients.4

With the belief that a strong primary care system is conducive to improving population health, the NHS initiated reforms that encouraged primary care physicians to organise into collaborative arrangements. To this end, the Regione Emilia-Romagna (RER), a large northern region with a population of about 4.5 million, has recently launched a plan in its 11 Local Health Authorities to establish Patient-Centred Medical Homes to better coordinate patient care and help patients avoid unnecessary hospitalisations.

The identification of those patients who would benefit most from outreach efforts is fundamental to achieving these goals of promoting and practising population health in Patient-Centred Medical Homes. The RER has established three objectives for this project: (1) develop predictive models to identify patients at high risk of hospitalisation or death, (2) create ‘risk of hospitalisation’ patient profiles that provide information about their high-risk patients to the general practitioners in the newly formed Patient-Centred Medical Homes and (3) assess the extent to which these models and reports provide additional information useful in the identification of patients who may benefit from case management or disease management.

This paper will address the first of the three goals. We describe the development of a predictive model using the RER's regional longitudinal administrative healthcare database to help identify patients who are most at risk of hospitalisation for conditions that may be impacted through improved patient care. This model will then be used to inform the providers associated with the Patient-Centred Medical Homes and aid in their planning for care management and interventions that can reduce their patients’ likelihood of a preventable, high-cost hospitalisation.

Methods

Study data and study population

The model was developed using the population-based longitudinal healthcare database of the residents served by the RER Health Service in the years 2004 through 2012.5 This administrative database includes demographic information for all residents (gender, birth and death dates, location of current residence and primary care physician), hospital discharge abstract data (International Classification of Diseases-9-CM (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes, and admission and discharge dates), emergency room utilisation information, outpatient pharmacy data at the individual prescription level, specialty care (laboratory, diagnostics, therapeutic procedures, rehabilitation and specialist visits), home health data and information on each primary care physician in the region. Each patient has an anonymous identifier assigned by the RER so that an individual's utilisation can be tracked over time without jeopardising patient privacy.

The study population consisted of all residents of the RER who were at least 18 years of age and still alive as of 31 December 2011. Healthcare utilisation data from 2011 and history variables using data from 2004 through 2010 were used to predict outcomes in 2012.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was defined as the occurrence of a hospitalisation for problems that are potentially avoidable, or whose progression may have been avoided or delayed through appropriate patient care, or the death of the individual, either in or out of the hospital, for any reason, in 2012. We included deaths in the dependent variable since we believe that, for example, a patient with coronary artery disease who dies secondary to an acute myocardial infarction, should be included in the dependent variable even if the death is out of the hospital. We decided to not limit the hospitalisation to emergency admissions, since a planned admission may also be an indicator of a worsening medical problem. In order to operationally define the dependent variable, we (authors JSG and DZL) reviewed the Disease Staging6 7 primary diagnostic category and severity stage of all day and inpatient hospital admissions (for adults age 18+) in RER for 1 year, to select those admissions that should be included in the dependent variable.

Admissions to deliver a baby, admission for dental diseases or admissions for vague signs or symptoms with no identified aetiology were excluded. Admissions for problems that are not predictable/preventable were excluded while those where screening may identify problems that can potentially be treated to avoid progression were included. For example, admissions for stage 1, chronic cholecystitis or cholelithiasis were excluded, but admissions for advanced stage 2 or 3 complications such as ascending cholangitis or pancreatitis were included.

We felt that inclusion of hospitalisation for cancer in the dependent variable should depend on the ability to either prevent or avoid progression of the disease. We therefore included colon cancer and cervical cancer in the definition because they are potentially preventable, but excluded all other cancers where prevention/prediction is not currently possible.

Inclusion of injuries, burns or toxic reaction to prescription or non-prescription drugs would ideally be based on the cause of these problems. Since the aetiology of these problems is typically not available in the administrative data being used in this project, we made the decision to include or exclude based on our subjective judgment of the likelihood of preventability. For example, adverse drug reactions were included but burns were excluded from the definition of the dependent variable.

There is no obvious medical reason for a hospital admission for patients with stage 1 diabetes mellitus or stage 1 essential hypertension without complications. These problems are typically treatable in the outpatient setting. A hospitalisation implies a potential problem in the care of these patients, so we decided to include these admissions as a part of the dependent variable.8

Independent variables

A broad range of candidate predictor variables was developed taking advantage of the RER administrative data. The independent variables used for modelling were defined from the RER administrative data for the years 2004 through 2011. Demographic data included patient age, sex and geographic location of residence. We developed a mapping to broad disease categories defined primarily in terms of the affected body system from home healthcare data, pharmacy data and hospital discharge abstract data (see online supplementary appendix 1).

For those patients who had been hospitalised, more specific diagnostic data were available. We reviewed the classification of patients hospitalised historically using the Disease Staging diagnostic category and disease severity stages.7 8 Based on the frequencies, specific diagnostic category/stage predictor variables were defined for either specific stages of frequent diseases, or by combinations across similar categories. Predictor variables were defined based on the number of emergency room visits using the RER classifications system for the urgency of the visit.

Pharmacy data were used to identify polypharmacy9 (defined as the simultaneous use of five or more active ingredients for at least 15 consecutive days), potential drug–drug interactions10 and potentially inappropriate medication use in patients11 65 years and older. Since cardiovascular disease is highly prevalent, we reviewed the use of cardiovascular drugs and created a variable for each of the following 11 classes of drugs (oral anti-coagulants, β-blockers, ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, anti-platelets, calcium channel blockers, anti-arrhythmics, digitalis glycosides, nitrates, diuretics, α-blockers, statins) to account for the complexity of therapeutic regimen at the patient level.

To take advantage of the fact that the RER database includes multiple years of data, we created history variables using the utilisation for each year of data available. Since we were working with the 2011 data to predict hospitalisation or death in 2012, we created history variables based on 2004–2010 data. This set included 83 of the diagnostic category/stage variables as well as 11 variables based on pharmacy utilisation such as exposure to polypharmacy and use of cardiovascular drugs. If the individual had a history of a disease in any of the years from 2004 to 2010 they were flagged as having a history of that disease and this was used as a potential predictor variable.

Modelling

Logistic regression models were used to estimate predicted probabilities for the occurrence of an inpatient hospital stay for the selected conditions or death for individual patients. Risk of hospitalisation or death, and the variables that relate to those risks are highly dependent on age and gender. Regression models were fit in each of 14 gender and age strata using SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). A stepwise process with relaxed covariate entry and retention criteria (inclusion p value ≤0.8, retention ≤0.5) was used. At each step in this process, an attempt is made to remove any unimportant variables from the model before adding a potentially important variable. Each addition or deletion of a variable to or from a potential model is a separate step and, at each step, a new model is fitted. This process results in a reduced, but robust set of independent variables that predict outcome or that might have importance as adjustment terms for the model in each age/gender stratum.

Evaluation of the models

The predictive accuracy of the modelling was evaluated using C-statistics (the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve), along with three measures traditionally used with clinical screening tools: sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value (PPV).

C-statistics were used to evaluate the models in two ways. The first evaluation consisted of fitting the model developed using utilisation and demographic data from 2011, along with historical variables based on 2004–2010 data, and outcomes (hospitalisation or death) from 2012 and then computing a C-statistic to evaluate how the models performed at predicting those outcomes on which the models were conditioned. However, this evaluation is not consistent with evaluating how the data are used in practise. In practise, we have current predictor information, but the outcomes have not been realised. To better estimate how the models are likely to perform in this setting, we fit models to outcomes data up to a year prior to the most current available (eg, 2011 outcomes modelled with predictors from 2010, along with historical variables based on 2004–2009 data). We then computed a C-statistic for projections made on the risk of hospitalisation or death outcomes (in 2012) using the next year's predictor information (in 2011). This way, the models are forced to make projections into the future, but we have the actual observed outcomes data to evaluate the modelling process as it would be used in practise. The resulting C-statistics obtained from these two model runs were compared.

In order to evaluate the performance of the model across different risk thresholds we classified predicted risk scores. ‘Very high risk’ was defined as patients with a predicted risk of hospitalisation or death in the following year of ≥25% while ‘high risk’ was defined as patients with a predicted risk of hospitalisation of 15–24%. These risk thresholds were selected after consultation with physicians practising in the medical homes to yield a total of about 10% of the 1500 patients enrolled with a typical primary care physician.

Results

Among the 3 726 380 adult residents of Emilia-Romagna at the end of 2011, 449 163 (12.1%) were hospitalised in 2012; 4.2% were hospitalised for the selected conditions defined earlier or died in 2012 (3.6% hospitalised, 1.3% died).

Table 1 shows the distribution of the demographics (age and gender), number of chronic conditions, body systems impacted by the selected chronic conditions, and polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing among the eligible RER residents, as of 31 December 2011. Table 1 also compares these characteristics of the total adult population of the region to the subgroups of the population classified in the ‘very high risk’ and ‘high risk’ categories. Based on the model results, 114 255 individuals were identified as having a predicted risk of hospitalisation or death in 2012 of ≥25% and classified as ‘very high risk.’ An additional 134 610 individuals had a predicted risk of hospitalisation or death in 2012 of 15–24% and were classified as ‘high risk.’

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the Regione Emilia-Romagna population, overall and by risk category

| Total population* |

Very high risk† |

High risk† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 726 380 |

114 255 |

134 610 |

||||

| Number | Per cent | Number | Per cent | Number | Per cent | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1 788 048 | 48.0 | 54 357 | 47.6 | 61 803 | 45.9 |

| Female | 1 938 332 | 52.0 | 59 898 | 52.4 | 72 807 | 54.1 |

| Age groups | ||||||

| 18–24 | 258 338 | 6.9 | 76 | 0.1 | 105 | 0.1 |

| 25–34 | 499 786 | 13.4 | 302 | 0.3 | 391 | 0.3 |

| 35–44 | 732 626 | 19.7 | 1137 | 1.0 | 1198 | 0.9 |

| 45–54 | 676 047 | 18.1 | 2612 | 2.3 | 2485 | 1.8 |

| 55–64 | 550 689 | 14.8 | 5391 | 4.7 | 5287 | 3.9 |

| 65–74 | 482 346 | 12.9 | 13 154 | 11.5 | 14 471 | 10.8 |

| 75–84 | 364 369 | 9.8 | 33 430 | 29.3 | 44 857 | 33.3 |

| 85+ | 162 179 | 4.4 | 58 153 | 50.9 | 65 816 | 48.9 |

| Number of chronic conditions | ||||||

| 0–1 | 2 775 888 | 74.5 | 8176 | 7.2 | 24 618 | 18.3 |

| 2 or more | 950 492 | 25.5 | 106 079 | 92.8 | 109 992 | 81.7 |

| 5 or more | 99 337 | 2.7 | 45 445 | 39.8 | 20 576 | 15.3 |

| Selected conditions/body systems | ||||||

| Cancer | 99 328 | 2.7 | 23 872 | 20.9 | 14 305 | 10.6 |

| Cardiovascular | 967 796 | 26.0 | 96 157 | 84.2 | 103 749 | 77.1 |

| Male genitourinary‡ | 130 609 | 7.3 | 14 616 | 26.9 | 16 776 | 27.1 |

| Ear, nose, throat | 5364 | 0.1 | 240 | 0.2 | 242 | 0.2 |

| Endocrine | 429 528 | 11.5 | 40 653 | 35.6 | 37 471 | 27.8 |

| Eye | 114 117 | 3.1 | 9,558 | 8.4 | 13 478 | 10.0 |

| Gastrointestinal | 580 946 | 15.6 | 74 718 | 65.4 | 66 305 | 49.3 |

| Gynaecological§ | 21 806 | 1.1 | 333 | 0.6 | 405 | 0.6 |

| Haematological | 45 022 | 1.2 | 15 353 | 13.4 | 6591 | 4.9 |

| Hepatobiliary | 24 785 | 0.7 | 6,477 | 5.7 | 3306 | 2.5 |

| Immunological | 3281 | 0.1 | 464 | 0.4 | 273 | 0.2 |

| Infectious disease | 4723 | 0.1 | 2207 | 1.9 | 727 | 0.5 |

| Musculoskeletal | 419 184 | 11.2 | 43 436 | 38.0 | 41 000 | 30.5 |

| Neurological | 173 751 | 4.7 | 34 494 | 30.2 | 24 838 | 18.5 |

| Psychological | 291 308 | 7.8 | 43 387 | 38.0 | 33 715 | 25.0 |

| Respiratory | 176 830 | 4.7 | 39 082 | 34.2 | 21 763 | 16.2 |

| Skin | 28 339 | 0.8 | 7,645 | 6.7 | 3,008 | 2.2 |

| Urogenital | 37 728 | 1.0 | 16 501 | 14.4 | 5,740 | 4.3 |

| Polypharmacy¶ | 609 278 | 16.4 | 92 153 | 80.7 | 92 156 | 68.5 |

| Any potentially inappropriate medications (age 65 years or older)** | 257 033 | 25.5 | 51 055 | 48.7 | 49 003 | 39.2 |

*Adults (age 18 or older) and alive at 31 December 2011.

†‘Very high risk’ was defined as patients with a predicted risk of hospitalisation or death in the following year of ≥25% while ‘high risk’ was defined as patients with a predicted risk of hospitalisation of 15–24%.

‡Men only.

§Women only.

¶Polypharmacy is defined as the simultaneous use of five or more active ingredients for at least 15 consecutive days.

**The list of potentially inappropriate medications can be found in ref. 11.

There was little difference across the risk categories by gender. Age distributions for the ‘very high risk’ and ‘high risk’ groups were shifted more towards the older age groups than those in the overall study population. Residents age 85 or older represented about 4.5% of the RER population, but about 50% of the ‘very high’ and ‘high’ predicted risk groups. More than 75% of the residents over age 85 were classified as ‘very high’ or ‘high’ risk. However, age alone was not sufficient to predict their risk. For example, residents between 75 and 84 years of age made up 23% of the ‘very high’ risk group and 41% of the ‘high’ risk group, but over 85% of the residents in this age category had neither ‘very high’ nor ‘high’ predicted risk.

Across age and gender strata, demographics and healthcare utilisation experience in 2011 were the most commonly used independent variables for predicting hospitalisation or death in 2012. Selected history variables flagging chronic problems such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure, and a history of prescriptions for cardiovascular medications and polypharmacy were also significant predictors.

The residents in the two higher risk groups were more likely than others to have multiple chronic diseases and to experience polypharmacy and inappropriate medication use. The residents identified as ‘very high risk’ or ‘high risk’ by the model also showed a number of striking differences from others in terms of the occurrence of some of the most prevalent health conditions by type and body system. Although cardiovascular conditions were not uncommon in the total adult population (26.0%), they were far more common among those classified as ‘very high risk’ and ‘high risk’ (84.2% and 77.1%, respectively). Similarly, gastrointestinal conditions affected 15.6% of the total population, but were diagnosed in 65.4% of the ‘very high risk’ and 49.3% of the ‘high risk’ patients. Cancer occurred in 2.7% of the total population, but 20.9% of the ‘very high risk’ and 10.6% of the ‘high risk’ patients had a cancer diagnosis. Mental health problems were identified in 7.8% of the adult population, but in 34.2% of the ‘very high risk’ and 25.0% of the ‘high risk’ patients.

The C-statistic for the model of 2012 outcomes developed using 2011 predictors and the C-statistic based on the parameters from the model of 2011 outcomes regressed on 2010 predictors applied to the 2011 predictors and 2012 outcomes were very similar (0.856 and 0.853, respectively). These results suggest that the relationship between predictors and risk of hospitalisation changed little in 1 year and that model parameters developed in a prior year can be used reliably with the most current year's data to predict unknown outcomes in the next year with only a minimal loss in performance in this population.

Table 2 shows the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and number of true positives for the model at the two selected cut-off points. The sensitivity (percentage of patients actually hospitalised who had been identified by the model as having a predicted risk higher than the cut-off point) was 29.8% for those with the ‘very high’ risk scores. This percentage represents 46 950 of the 157 550 residents of the region who were hospitalised for a selected condition or died in 2012. If we modify the risk score threshold to include individuals with a predicted risk of hospitalisation for selected conditions or death of ≥15% (ie, both the ‘very high risk’ and the ‘high risk’ patients), the sensitivity is 0.471. The true negative rate (specificity) is very high for both risk thresholds (0.981 and 0.951, respectively).

Table 2.

Performance of the ‘Risk of Hospitalisation’ model for residents identified as ‘Very High Risk’ and ‘High or Very High Risk’

| Measure | Cut-off points for comparison |

|

|---|---|---|

| ‘Very high risk’* | ‘Very high risk’* +‘High risk’† | |

| Sensitivity‡ | 0.298 | 0.471 |

| Specificity§ | 0.981 | 0.951 |

| Positive predictive value¶ | 0.411 | 0.298 |

| True positives** | 46 950 | 74 196 |

*‘Very high risk’ is defined as patients with a predicted risk of hospitalisation of ≥25%.

†‘Very high risk’+‘High risk’ is defined as patients with a predicted risk of hospitalisation of ≥15%.

‡Sensitivity is defined as the proportion of those hospitalised who were predicted to be hospitalised (true positive rate).

§Specificity is the proportion of those not hospitalised who were not predicted to be hospitalised (true negative rate).

¶Positive predictive value is the proportion of those predicted to be hospitalised who were actually hospitalised.

**True positives are the number of residents who were predicted to be at risk for hospitalisation at the predicted risk threshold and were actually hospitalised.

The model appears to be well calibrated across levels of risk. Figure 1 depicts the RER population divided into groups by deciles of predicted risk of hospitalisation or death from the models. The observed prevalence of hospitalisation or death is compared to the average predicted risk among individuals in each of the ten predicted risk groups. For example, the overall rate of hospitalisation for the selected conditions or death in 2012 was 4.2%. For those patients in the highest predicted risk decile group, the average predicted risk was 23.9% and the actual prevalence of hospitalisation or death was 24.2%. (Regression coefficients and significance levels of independent variables for models for each of 14 age and gender strata are displayed in online supplementary appendix 2).

Figure 1.

Model calibration: predicted risk and observed prevalence of hospitalisation or death in 2012 by predicted risk decile groups.

Discussion

We have developed a population-based model that identifies the risk of hospitalisation for all adult RER residents and does so with a level of performance (c=0.85) as high as, or higher than, similar models. In addition, we believe that the definition of the dependent variable chosen for our models increases the probability that they are identifying patients at risk who can potentially be improved by appropriate care. A systematic review by Kansagara12 of models designed to predict readmissions, showed C-statistic results in the range of 0.55 to 0.83. Recent work by Billings et al13 to develop models predictive of emergent admissions in the UK had results ranging from 0.73 to 0.78. Li Wang et al (2013),14 using information available through the USA Department of Veterans Affairs, which also included lab data, demonstrated C-statistics of 0.81 and 0.79, respectively, for their models of 90-day or 12-month hospitalisation or death outcomes. At a predicted risk of ≥25% our model had a PPV of 0.411. Billings et al14 reported a PPV of 0.417 at a risk threshold of 30. There is a trade-off in using our model, or any predictive model, between the threshold for follow-up and predictive accuracy. A lower risk threshold would identify more patients but with a lower prevalence of hospitalisation or death.

Although previous studies have developed models predictive of hospital care, these models fall short of the needs of the Patient-Centred Medical Homes being implemented in RER. Typically, these models have focused on specific age groups,15 conditions or types of admissions, such as emergent14 or unplanned admissions, or rehospitalisations, or health insurance plans in the USA, including private insurance plans, and Medicare and Medicaid plans.16 17 The models we have developed are applied to the entire adult population of RER. They use existing administrative data, which makes them cost-effective to apply.

Patient-Centred Medical Homes, including those instituted in RER, are responsible for addressing the needs of their population and making the best use of their finite resources to accomplish this. Preventing unnecessary admissions could improve the quality of care as well as health status of the enrolled population, and result in substantial savings. To accomplish this, predictive models and risk stratification tools such as those developed for this project are needed to identify patients at risk of preventable admissions and provide information that can be used by the medical homes to help manage care.

There are some limitations to the model. The model is developed from administrative data. Administrative data are collected for reimbursement and tracking utilisation and not for medical research. They lack the clinical specificity that would be desirable in assessing an individual's medical problems. Patients with medical problems who have not used the services included in the database cannot be identified. While the hospital discharge abstract data do include diagnostic information coded using ICD-9-CM, no similar data are available for outpatient encounters in the RER database. The mortality data available for this project did not include information about cause of death. Therefore, some proportion of patients whose death was not predictable were included, limiting model performance. In addition, our models use prior utilisation among the predictor variables. With the administrative data we cannot distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate treatment, which may bias our results.

Despite the limitations of administrative data, they have many advantages for this project: they are readily available, relatively inexpensive to analyse and cover large populations over many years. They are ideal for uncovering patterns of care. If information from medical records is needed, the results of these analyses can then be supplemented by focused clinical reviews at the local level. Also, The RER has a system in place to monitor the quality of diagnosis and procedure coding in their hospital discharge abstract data. Controls at both the hospital and regional level assess the validity of coding and the consistency of codes assigned, such as congruity between sex, age and diagnosis, and between diagnosis and procedure. The existence of the RER administrative database made it feasible to develop the models described in this article at relatively low cost and to update the models over time without additional data collection that others have found necessary.14

Currently, these risk scores are being integrated with other information in profiles of high-risk patients furnished to providers in 12 newly formed medical homes, including 83 primary care physicians serving a total of about 100 000 patients, in the Parma Local Health Authority located in RER. Along with the risk scores, this information includes data about previous hospitalisations, use of referrals, medications, long-term care and home care services, and a number of process-like quality indicators for diabetic and cardiovascular patients, and for appropriate medication use in older patients.

We believe that the Italian healthcare system offers a number of advantages in the goal of reducing potentially avoidable hospitalisation. Every Italian must enrol with a primary care physician. The population is quite stable with modest levels of change of residence or change of primary care physician. Every Italian is entitled to healthcare with little or no cost at the point of service. There is no problem with loss of, or change in, insurance coverage. Primary care physicians are primarily paid on a per capita basis. However, the Emilia-Romagna region has the ability to negotiate incentive payments designed to address and monitor improvements in medical management such as that addressed in our study.

Of course, model results need to lead to effective interventions to have a positive impact on patient care. To this end, we are working with the physicians, nurses and other healthcare professionals as well as the administration of the newly formed Medical Homes in Parma to assist them in understanding how to use the results of these models and in developing potentially effective interventions. The individual profiles of high-risk patients provided to the healthcare team in the Medical Homes allow them to trigger specific actions such as inviting patients to enrol in disease management programmes for chronic problems such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or diabetes mellitus, activating home health assistance, initiating a medication review or recommending that the patient come in for an office visit. An evaluation of the use and usefulness of the profiles and intervention is under way.

In summary, these models provide a means of identifying patients at high risk for hospitalisation. The risk predictions, in conjunction with the risk profile, show promise as a useful organisational tool for the regional Patient-Centred Medical Homes to develop and implement proactive case management and disease management programmes. The RER is reviewing the results of the Parma Local Health Authority pilot project of the profiles. Once their usefulness has been further evaluated, their use will be expanded to other Medical Homes in development in the other Local Health Authorities in the Emilia-Romagna region. If similar data are available, these models can be applied in other Italian regions and other countries investing in organisation similar to the Patient-Centred Medical Home.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DZL, RG, VM and JSG were responsible for the conceptualisation of this project. MR, JM and ML were responsible for creation of the data sets used in this project. DZL,VM, MR and JSG were responsible for the definition of analytical variables. SWK, MR, ML and JM were responsible for modelling and statistical analysis. DZL managed the research team. RG and JSG advised on the analyses and results. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was funded by the Agenzia Sanitaria e Sociale of the Emilia-Romagna Region, Italy. The resulting models are being used by the Local Health Authority of Parma, Italy and the Patient-Centred Medical Homes located in the Parma Local Health Authority.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interests form and declare grants from the Regione Emilia-Romagna (Louis, Robeson, McAna, Maio, Keith, Liu, Gonnella) during the conduct of the study. Louis and Gonnella declare personal fees from Truven Health Analytics, The National School of Public Health, Portugal, INSIEL Mercato.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Thomas Jefferson University as an expedited retrospective database/record review. The IRB granted a waiver of informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Calnan M, Hutten, J, Tiljak H. The challenge of coordination: the role of primary care professionals in promoting integration across the interface, 85–104. In Saltman RB, Rico A, Boerma W, eds. Primary care in the driver's seat? Organizational reform in European primary care. New York: Open University Press World Health Organization European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Series, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith J, Goodwin N. Towards managed primary care: The role and experience of primary care organizations. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Defining the PCMH. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. http://www.pcmh.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt/community/pcmh__home/1483/pcmh_defining_the_pcmh_v2 (accessed 30 Jun 2013)

- 4.Lo Scalzo A, Donatini A, Orzella L, et al. Italy: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2009;11:1–216 [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Emilia-Romagna Regional Health Service and the new welfare system: Facilities, expenditure, and activities as of 31.12.2010. Programs, agreements and organisational models. Bologna, Italy: Regione Emilia-Romagna Assessorato Politiche per la Salute, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonnella JS, Hornbrook MC, Louis DZ. Staging of disease: a case-mix measurement. JAMA 1984;251:637–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonnella JS, Louis DZ, Gozum ME, et al. , eds. Clinical Criteria for Disease Staging. 6th edn. Ann Arbor, MI: Truven Health Analytics, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louis DZ, Taroni F, Melotti R, et al. Increasing appropriateness of hospital admissions in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy. J Health Serv Res Policy 2008;13:202–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slabaugh L, Maio V, Templin M, et al. Prevalence and risk of polypharmacy amongst elderly primary care patients in Regione Emilia-Romagna, Italy. Drug Aging 2010;27:1019–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagne JJ, Maio V, Rabinowitz C. Prevalence and predictors of potential drug-drug interactions among ambulatory patients in regione Emilia-Romagna, Italy. J Clin Pharm Ther 2008;33:141–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maio V, Del Canale S, Abouzaid S. Using explicit criteria to evaluate the quality of prescribing in elderly Italian outpatients: a Cohort study. J Clin Pharm Ther 2010;35:219–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs US, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billings J, Georghiou T, Blunt I, et al. Choosing a model to predict hospital admission: an observational study of new variants of predictive models for case finding. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Porter B, Maynard C, et al. Predicting risk of hospitalization or death among patients receiving primary care in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care 2013;51:368–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inouye SK, Zhang Y, Jones RN, et al. Risk factors for hospitalization among community-dwelling primary care older patients: development and validation of a predictive model. Med Care 2008;46:726–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemke KW, Weiner JP, Clark JM. Development and validation of a model for predicting inpatient hospitalization. Med Care 2012;50:131–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAna JF, Crawfrod AG, Novinger BW, et al. A predictive model of hospitalization risk among diabled Medicaid enrollees. Am J Manag Care 2013;19:166–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.