Abstract

Introduction

Postoperative delirium is one of the most common complications of major surgery, affecting 10–70% of surgical patients 60 years and older. Delirium is an acute change in cognition that manifests as poor attention and illogical thinking and is associated with longer intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital stay, long-lasting cognitive deterioration and increased mortality. Ketamine has been used as an anaesthetic drug for over 50 years and has an established safety record. Recent research suggests that, in addition to preventing acute postoperative pain, a subanaesthetic dose of intraoperative ketamine could decrease the incidence of postoperative delirium as well as other neurological and psychiatric outcomes. However, these proposed benefits of ketamine have not been tested in a large clinical trial.

Methods

The Prevention of Delirium and Complications Associated with Surgical Treatments (PODCAST) study is an international, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. 600 cardiac and major non-cardiac surgery patients will be randomised to receive ketamine (0.5 or 1 mg/kg) or placebo following anaesthetic induction and prior to surgical incision. For the primary outcome, blinded observers will assess delirium on the day of surgery (postoperative day 0) and twice daily from postoperative days 1–3 using the Confusion Assessment Method or the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU. For the secondary outcomes, blinded observers will estimate pain using the Behavioral Pain Scale or the Behavioral Pain Scale for Non-Intubated Patients and patient self-report.

Ethics and dissemination

The PODCAST trial has been approved by the ethics boards of five participating institutions; approval is ongoing at other sites. Recruitment began in February 2014 and will continue until the end of 2016. Dissemination plans include presentations at scientific conferences, scientific publications, stakeholder engagement and popular media.

Registration details

The study is registered at clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01690988 (last updated March 2014). The PODCAST trial is being conducted under the auspices of the Neurological Outcomes Network for Surgery (NEURONS).

Trial registration number

NCT01690988 (last updated December 2013).

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Since the Prevention of Delirium and Complications Associated with Surgical Treatments (PODCAST) study is a multicentre international trial, the results of the study will potentially be generalisable.

This trial has a novel focus of assessing delirium and pain concurrently. Results could reveal that these two outcomes are potentially linked in the postoperative setting.

Investigators assessing for delirium have been appropriately trained and will use reliable and validated assessment tools.

The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) is not a validated pain assessment instrument in delirious patients. In an attempt to mitigate this limitation, pain will also be assessed observationally using the Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) and the Behavioral Pain Scale—Non-Intubated (BPS-NI).

Delirium is fluctuating in nature. Since patients will be assessed at discrete time points, it is possible that some episodes of delirium will not be detected.

Introduction

Background and rationale

Delirium

Postoperative delirium is one of the most common complications of major surgery and affects between 10% and 70% of all surgical patients older than 60 years (table 1).1 The estimated additional healthcare costs associated with delirium exceed $60 000 per patient per year.2 While causal relationships have not been established, delirium is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, prolonged length of hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) stay, functional and cognitive decline with nursing home or long-term care facility placement.3–6 Furthermore, the acute deterioration in cognition and psychomotor agitation frequently seen with delirium is often distressing for both patients and their families.

Table 1.

Incidence of delirium in major surgeries

| Surgery type | Study | Population | Delirium rate (%) | Detection method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unselected | Radtke et al7 | Recovery room after elective general anaesthesia | 9.9 | Nu-DESC |

| Surgical ICU | Pandharipande et al8 | Surgical ICU | 73 | CAM-ICU |

| Trauma ICU | 67 | |||

| Head and neck | Weed et al9 | Major head and neck | 17 | Not stated |

| Cardiac | Kazmierski et al10 | Cardiac surgery with CPB | Age <60: 16.3 Age ≥60: 24.7 |

DSM-IV |

| Rudolph et al11 | Patients >60 undergoing elective or urgent cardiac surgery | 43 | CAM | |

| Saczynski et al12 | Patients >60 undergoing elective coronary artery bypass grafting or valve replacement surgery | 46 | CAM | |

| Vascular | Marcantonio et al,13 Schneider et al,14 Bohner et al15 and Benoit et al16 | Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | 33–54 | CAM or DSM-IV |

| Schneider et al14 and Bohner et al15 | Peripheral vascular | 30–48 | DSM-IV | |

| Orthopaedic | Fisher and Flowerdew17 | Patients >60 undergoing elective orthopaedic procedures | 17.5 | CAM |

| Marcantonio et al18 and Lee et al19 | Patients >65 undergoing emergent hip fracture repair | 30.2–41 | CAM |

CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition; ICU, intensive care unit; Nu-DESC, The Nursing Delirium Screening Scale.

The diagnostic criteria for delirium have recently been updated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-V). Delirium is an acute neurocognitive disorder characterised by a fluctuating level of consciousness with impairment of attention and cognition. In the postoperative context, delirium typically manifests between 0 and 96 h following surgical intervention. It is unclear why postoperative delirium occurs so frequently. Age greater than 60, male gender, history of dementia or depression, sensory impairment and chronic medical illness are consistently described as risk factors for delirium.20 No effective prophylactic or curative treatments for postoperative delirium have been identified.

Ketamine and delirium

Ketamine is an anaesthetic agent that has been in common use for more than 50 years. It has a wide margin of safety, and as of 2005 had been studied in over 12 000 operative and diagnostic procedures, involving over 10 000 patients from 105 separate studies (ketamine package insert 2005). There is a pharmacological rationale for using ketamine as a preventative measure against postoperative delirium based on its N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonism.21 Normally, excitatory amino acids such as glutamate and aspartate act as agonists at NMDA receptors, and in the setting of surgery and inflammation, they might promote excitotoxic injury and apoptosis.21 As an NMDA antagonist, ketamine has the potential to protect against such neurological injury.22 Ketamine has also been posited to inhibit HCN1 receptors, which mediate the hyperpolarisation-activated cation current.23 Such inhibition is pertinent to delirium because HCN1 channels are important for regulating states of consciousness24 and are upregulated by inflammation.25 HCN1 receptors are also thought to play a critical role in neuropathic pain through inflammatory cascades.26

On the basis of the pharmacological rationale for neuroprotection, a 58-patient randomised controlled trial was conducted to determine whether ketamine might prevent delirium after major cardiac surgery.27 There was a significant reduction in postoperative delirium from 31% to 3% with the administration of low-dose ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) on induction of anaesthesia. Although encouraging, this trial must be regarded as preliminary owing to its small sample size and single-centre design. Interestingly, the same investigators also found that ketamine was associated with improved cognition beyond the immediate postoperative period.28 Differences between the ketamine and placebo groups were evident in tests of non-verbal memory, verbal memory and executive function. The investigators found that C reactive protein, a non-specific inflammatory marker, was similar at baseline in the ketamine and placebo groups. On the first postoperative day, C reactive protein was elevated in both groups, but was significantly higher in the placebo group. The investigators hypothesised that the neuroprotective effect of ketamine might have been, in part, attributable to its anti-inflammatory actions.28 In support of the plausibility of this hypothesis, ketamine use in another cardiac surgical population was similarly shown to attenuate postoperative increases in inflammatory markers.29

An intraoperative subanaesthetic dose of ketamine is appealing as a potential preventative intervention for delirium, since it is inexpensive and has an excellent safety profile. A number of questions remain to be answered regarding postoperative delirium. Despite the fact that delirium is a common and serious postoperative complication, intraoperative factors contributing to pathogenesis have not been rigorously investigated, and only a few small trials have been conducted that examine interventions to decrease its incidence. It is also currently unknown whether postoperative delirium is preventable, particularly in patients with underlying vulnerabilities. Importantly, ketamine in higher (anaesthetic) doses has become less popular over time owing to its side effects, including hallucinations and emergence reactions, especially in younger patients.30 31 To ensure treatment effectiveness, the preliminary results identifying subanaesthetic doses of ketamine as a useful preventative intervention for postoperative delirium should therefore be confirmed or refuted using a large-scale, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial design prior to routine adoption of low-dose ketamine for this purpose.

Acute and persistent pain

Similar to delirium, both acute and persistent pain are common postoperative complications, with a negative impact on patients’ lives. The Joint Commission has established the prevention of severe postoperative pain as a benchmark of quality,32 and adequate pain management is increasingly viewed as a fundamental human right.33 34 Unfortunately, this standard of care has not been attained to date; it has previously been estimated that about a third of patients suffer severe acute postsurgical pain following major procedures.35 Furthermore, patients who have acute postoperative pain are more likely to develop chronic pain, and the incidence of persistent postoperative pain following major surgeries remains between 5% and 30%.36 As an antagonist at NMDA and HCN1 receptors, ketamine has powerful analgesic properties. A systematic review showed that a single subanaesthetic dose of intraoperative ketamine was associated with decreased visual analogue pain scores up to 48 h postoperatively.37 At 24 h postoperatively, ketamine was associated with an impressive 16 mg decrease in total morphine consumption.37 Furthermore, adverse effects such as hallucinations were rarely reported when low-dose ketamine was administered during general anaesthesia.37 Consistent with these findings, a Cochrane systematic review reported that subanaesthetic doses of perioperative ketamine were associated with decreased postoperative pain, decreased morphine consumption and decreased nausea and vomiting.38 Adverse effects were mild or absent.38 An updated systematic review, which included 70 small studies involving 4701 patients, recently confirmed that, in a dose-dependent manner, subanaesthetic intraoperative ketamine was consistently associated with decreased postoperative pain despite decreased opioid consumption.39 The more painful the surgical procedure, the greater was the analgesic benefit attributable to ketamine.39 In keeping with the decreased opioid consumption, postoperative nausea and vomiting were also less frequent in patients who received ketamine. However, patients who had been randomised to ketamine reported hallucinations and nightmares more frequently.39 While efficacy data, based on numerous small studies, strongly suggest that supplementary ketamine should be used to decrease pain and opioid usage postoperatively, most practitioners have not incorporated low-dose ketamine into their routine practice. Preliminary data gathered from five institutions (see below for details) involved in the Prevention of Delirium and Complications Associated with Surgical Treatments (PODCAST) trial suggest that despite their knowledge regarding the analgesic and opioid-sparing effects, practitioners do not administer low-dose ketamine for pain because of concern for complications such as delirium. Thus, effectiveness data regarding the relationship of ketamine, delirium and pain are needed.

Although numerous small efficacy studies have shown that ketamine decreases acute postoperative pain, its role in preventing persistent postoperative pain has not been rigorously explored. Many causal mechanisms that are thought to be implicated in persistent pain and a single intraoperative intervention might not be sufficient to decrease its occurrence. However, there have been encouraging findings about the potential of NMDA antagonists to decrease postoperative persistent pain. In the ENIGMA trial, patients were randomised to receive intraoperative oxygen with either nitrogen or nitrous oxide, which, like ketamine, is an NMDA antagonist. The investigators found that among those patients who received nitrous oxide, there was an absolute decrease in the percentage of patients who experience persistent pain (baseline incidence=15%) at 3 months postoperatively of 7% (95% CI 1.9% to 13.9%).40 A randomised study has examined the potential beneficial effect of intraoperative ketamine on persistent postoperative pain among patients undergoing total hip replacement.41 This trial found a reduction in the ketamine group from 21% to 8% (reduction=13%; 95% CI 1.3% to 24.9%) in patients experiencing persistent pain at 6 months after their surgery.41 The PODCAST study would demonstrate whether a subanaesthetic dose of intraoperative ketamine is effective at preventing acute postoperative pain in a real-world setting. If ketamine was shown to have a substantial effect in decreasing acute postoperative pain, a next step would be to investigate rigorously its impact on persistent pain.

Current utilisation of low-dose ketamine

A survey of anaesthesia clinicians was conducted at five of the institutions (Washington University in St Louis, University of Michigan, University of Manitoba, Weill Medical College of Cornell University and Medical College of Wisconsin) participating in the PODCAST clinical trial. In total, 270 clinicians responded to the surveys; 18% (range among institutions 12–40%) of respondents currently incorporate adjunctive subanaesthetic ketamine into their practice. Interestingly, 84% of survey respondents believe that low-dose ketamine decreases acute postoperative pain, 81% feel that it decreases postoperative opioid consumption and 51% believe that it decreases chronic postoperative pain. However, the reason that a minority of practitioners are currently administering adjunctive ketamine is probably because many remain concerned about the neurological side effects of even low-dose ketamine; 68% of respondents expressed concern about hallucinations, 62% about delirium and 55% about nightmares.

Potential impact of PODCAST

The PODCAST trial has a novel focus in that it is assessing the impact of an intervention (subanaesthetic racemic ketamine administration) on delirium and pain, two adverse and potentially linked outcomes that have not previously been jointly evaluated in a single large clinical trial. Both delirium and pain are surprisingly common acute postoperative complications with major negative consequences for patients.1 35 Currently, there are no official guidelines to screen patients for delirium, and only a few preventive measures have been investigated, with disappointing results. Since most patients with postoperative delirium have a hypoactive phenotype, it is frequently missed in clinical practice. As noted previously, postoperative delirium is associated with increased intensive care and hospital stay, with persistent cognitive decline and with increased mortality. Thus, any intervention that could decrease the incidence of postoperative delirium would probably have major positive implications for older patients undergoing surgical procedures. Unlike delirium, acute postoperative pain is routinely assessed, and the Joint Commission has prioritised the prevention of severe postoperative pain as a universal goal. Unfortunately, this objective has not been met, and both severe acute pain and debilitating chronic pain continue to afflict many surgical patients.35 36 Of note, both pain and its treatment with opioid analgesics can be risk factors for delirium. Opioid analgesics are the mainstay therapy for postoperative pain, but their administration is curtailed in older patients particularly for safety considerations regarding respiratory depression, but also for concerns about causing sedation and delirium.

Pragmatic trials are intended to generate evidence of effectiveness of a test, treatment, procedure or healthcare service.42 43 At present, there is a lack of pragmatic trials for candidate interventions to prevent important and common postoperative neurological and psychiatric complications including delirium and pain. Ketamine is a plausible prophylactic option for each of these neurological and psychiatric complications. The American Society of Anesthesiologists has published Practice Guidelines for the management of acute and chronic pain, which, based on small efficacy or observational trials, include ketamine as a treatment option.44 45 There are currently no guidelines for the prevention of postoperative delirium. Thus, a multicentre pragmatic trial comparing low-dose ketamine with placebo is timely. It is important to emphasise that any one of several potential results of the PODCAST trial will have important and immediate positive implications for older surgical patients. First, ketamine might decrease both delirium and pain. This result would provide clear support for a larger comparative effectiveness trial testing ketamine as a prophylactic measure for both of these outcomes. Second, ketamine might decrease pain without increasing delirium. This result would provide compelling data that encourage the use of ketamine to prevent pain without concern for cognitive side effects such as delirium. Third, ketamine might decrease delirium and have no impact on pain. Although the lack of effect on pain is unlikely, this result would also encourage further study of the use of prophylactic intraoperative ketamine. However, low-dose ketamine may be found to increase delirium, regardless of its impact on pain. This result would suggest that the incorporation of intraoperative ketamine into routine clinical practice for older surgical patients is not warranted and would negate the need for a larger pragmatic trial. Furthermore, the PODCAST trial will help determine ketamine dose-related effects by comparing two doses (0.5 and 1 mg/kg) to placebo. As such, all of these potential results of the PODCAST trial have the potential to impact clinical practice and will be generalisable to all older surgical patients undergoing major surgical procedures because of the permissive inclusion criteria and the simplicity of intervention.42

Methods and analysis

Study design

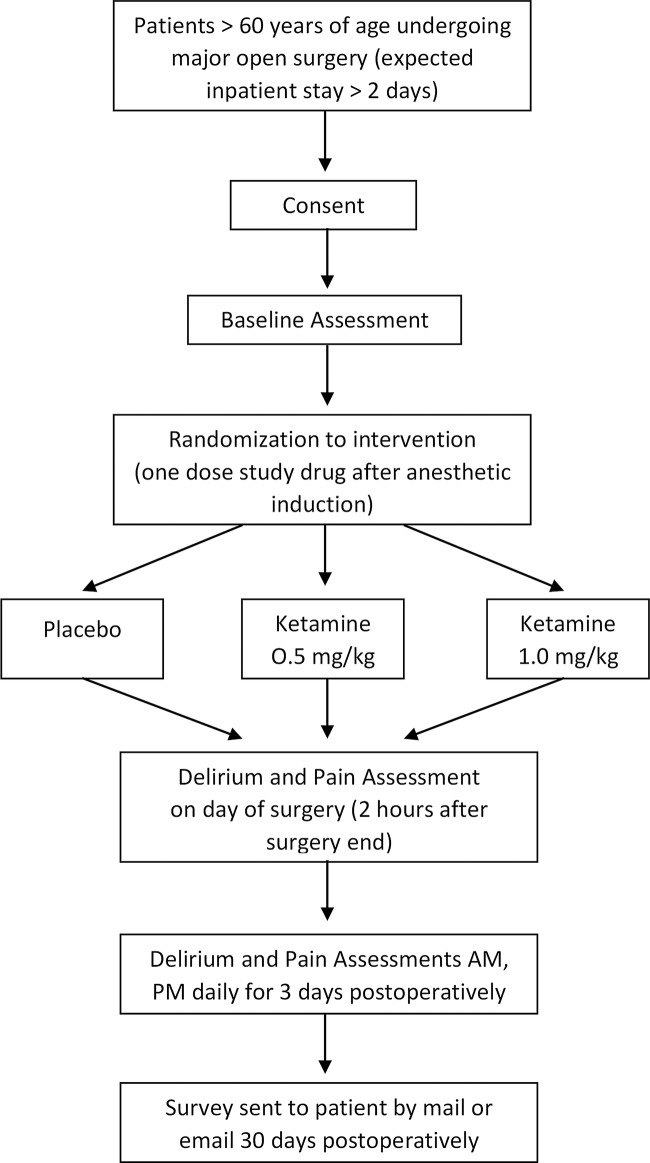

PODCAST is a prospective randomised controlled trial that has been designed in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines46 and will evaluate whether a single bolus dose of racemic ketamine (0.5 or 1 mg/kg) following induction of anaesthesia and before surgical incision decreases the incidence or severity of postoperative delirium and pain in a mixed elderly (>60 years) surgical patient population. Patients will undergo the standard preoperative anaesthesia assessment. Follow-up information will be collected from the medical chart for up to 5 years. The overall study design is outlined in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants.

Eligibility criteria

Patients 60 years old and older, who are competent to provide informed consent and who are undergoing major open cardiac surgery (eg, coronary artery bypass graft, valve replacement) or non-cardiac surgeries (eg, thoracic surgery, major vascular surgery, intra-abdominal surgery, open gynaecological surgery, open urological surgery, major orthopaedic surgery, hepatobiliary surgery and major ENT surgery) and receiving general anaesthesia, will be eligible for inclusion. The exclusion criteria are based on the contraindications to ketamine from the 2005 ketamine package insert. Patients with an allergy to ketamine and those in whom a significant elevation of blood pressure would constitute a serious hazard (eg, pheochromocytoma, aortic dissection) will be excluded. We shall also exclude patients with drug misuse history (eg, ketamine, cocaine, heroin, amphetamine, methamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine (MDMA), phencyclidine, lysergic acid, mescaline, psilocybin), patients taking antipsychotic medications (eg, chlorpromazine, clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, haloperidol, quetiapine, paliperidone, amisulpride, sertindole) and patients with a weight outside the range 50–200 kg (110–440 lbs). Patients will be enrolled either during a preoperative clinic visit or in the hospital prior to surgery.

Baseline assessment

At the time of enrolment, patients will undergo the same delirium and pain evaluation that will be used postoperatively (see Outcomes section). Additionally, patients will be screened for functional dependence using the Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living,47 for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8)48 and for obstructive sleep apnoea using the STOP-Bang criteria.49 Patients will be asked if they have a history of delirium, and if this presented after surgery. They will also be asked about any falls they have experienced in the 6 months prior to surgery. Comorbid conditions, including the components of the Charlson Comorbidity Index,50 will be obtained by reviewing the patients’ medical records. Any available preoperative laboratory results, including electrolytes and blood counts, will also be recorded.

Interventions

As this is a pragmatic trial, apart from administration of the study drug (ketamine or normal saline), all decisions about anaesthetic technique will be made by the anaesthetic team assigned to each patient. The only exception is that clinicians will be instructed not to administer any ketamine other than the study drug. The intention of this trial is to interfere as little as possible with the usual process of care, which will increase the applicability of the findings.43 Following the induction of general anaesthesia, an intravenous dose of 0.5 mg/kg racemic ketamine, 1 mg/kg racemic ketamine or an equivalent volume of normal saline will be injected via a reliable (free-flowing) central or peripheral intravenous line. Clinicians will be blinded to the treatment arm of the study. Anaesthetic factors such as the use of nitrous oxide, protocols for pain prevention, use of neuraxial anaesthesia, use of nerve blocks and other practices that could potentially affect primary or secondary outcomes will be assessed in a post hoc manner.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Trained members of the research team who are blinded to the treatment arm of the study will assess patients for delirium (primary outcome) using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)51 and the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU)52 53 for patients who are unable to speak (eg, have a tracheal tube or tracheostomy) on the ICU. These methods (the CAM and the CAM-ICU) have been shown to be reliable and to have good agreement with the DSM-IV criteria for delirium.53–55 Delirium assessments will be performed when patients can be aroused sufficiently in order to be assessed for delirium (Richmond Agitation and Sedation Score >−4). The first delirium assessment will be attempted if feasible on the day of surgery in the afternoon/evening. Patients will then be assessed for delirium twice daily (from postoperative day 1 to postoperative day 3) in the morning and in the afternoon/evening with at least 6 h between assessments. Each patient will be assessed for delirium up to seven times. At the Washington University site, the patients’ family members will perform the Family Confusion Assessment Method (FAM-CAM) separately from the investigators performing their assessments.56 Investigators and family members will be blinded to each other's assessments. The FAM-CAM has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for detection of delirium and good agreement with the CAM,56 but has not been specifically evaluated in the postoperative setting. After the final delirium assessment, patients will complete the Delirium and Pain Self-Assessment Questionnaire (see online supplementary appendix A). Incident delirium subsequent to this period is unlikely to be directly related to anaesthetic or other intraoperative factors.

Secondary outcomes

Study team members blinded to the treatment group of the patient will assess all secondary outcomes. Acute pain (secondary outcome) will be assessed prior to surgery and then postoperatively by using the Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS)57 or the Behavioral Pain Scale for the Non-Intubated patient (BPS-NI)58 and the 10 cm VAS (Visual Analog Scale) at the same times as patients are assessed for delirium. The BPS-NI has been shown to be a valid and reliable tool for measuring pain in a predominantly delirious patient population.58 Interviewers will rate the BPS or BPS-NI prior to asking the patient to complete the VAS to prevent bias in the BPS and BPS-NI assessments. The postoperative daily amount of opioids and sedatives administered will be ascertained from the patient's electronic health record spanning the period after surgery until the final delirium assessment is complete. After the final delirium assessment, patients will complete the Delirium and Pain Self-Assessment Questionnaire (see online supplementary appendix A). Postoperative nausea and vomiting (secondary outcome) will be assessed at the same time points that patients are assessed for delirium by asking patients to rate the severity of their nausea and vomiting, if present, on a three-point scale (mild, moderate, severe). Patients will be questioned at each assessment about side effects, especially hallucinations and nightmares. Intensive care unit and hospital length of stay will be obtained from the patient's medical record. At some of the participating sites in the PODCAST trial, patients will receive a survey, which will be sent by mail or email 1 month following surgery. This survey will collect patient-reported outcomes on depressive symptoms, affect, persistent pain, functionality and quality of life. Depressive symptoms will be assessed with the eight-item PHQ-8. Affect will be assessed with two 10-item mood scales that comprise the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) within 3–6 months postoperatively.59 The same screens for depressive symptoms and affect will also be conducted in the hospital on postoperative day 3. Persistent pain will be assessed with the Brief Pain Inventory Short Form (BPI-SF). The Barthel Index will be used to report functionality, and quality of life will be assessed from the Veteran's Rand-12 (VR-12) questionnaire.

Standardisation of training and outcomes assessment

All study team members who perform delirium assessments will undergo a rigorous training process. For the initial training, representatives from each study site participated in a full-day training programme led by SKI, the original creator of the CAM. Those who attended this initial training will oversee the training of other team members at their sites. Trainees must demonstrate competence at both conducting CAM interviews and in scoring these interviews. For the initial part of training, trainees must conduct at least two satisfactory CAM interviews in the presence of a trained team member. These interviews will not be on patients enrolled in the PODCAST trial. To establish their ability to score CAM interviews reliably, trainees will accompany trained team members to conduct CAM interviews. A trained member of the research team will conduct each CAM interview for patients enrolled in the PODCAST trial. The trainee will observe the interview, but will score the CAM independently. The trainee must agree with the trainer on the presence or absence of all 12 cognitive features assessed by the CAM on a minimum of two delirious and two non-delirious patients. After meeting the stipulations of training, the newly trained team member will conduct their first interview of a patient enrolled into the PODCAST trial in the presence of a previously trained team member.

Assessment of the standardisation and reliability of delirium assessments

After training, all PODCAST team members administering delirium assessments will be invited to participate in a project to demonstrate the validity and reliability of the CAM in our study population. Participants will view and rate eight videos of standard interviews depicting delirious and non-delirious patients. They will also independently score the CAM for each scenario. Demographic information, level of education, level of clinical experience and primary language will also be collected from all participants. Data will be de-identified. All scores and data will be submitted to the lead site, Washington University. The group's scores will then be compared to determine the reliability of delirium assessments across sites. Additionally, the group's scores will be compared with a set of ‘gold standard’ scores for the videos (determined by SKI's team). This comparison is intended to demonstrate the validity of the CAM in our study setting. Overall, the goal of the project is to demonstrate standardisation of the delirium outcome across all study sites.

Sample size

On the basis of the published delirium incidences in the scientific literature (table 1), we estimate conservatively that the incidence of postoperative delirium in a mixed major surgical population of older patients will be between 20% and 25%. Based on data from a substudy of the BAG-RECALL trial that we have recently completed, the incidence of delirium among patients admitted to our cardiothoracic intensive care unit at Barnes-Jewish Hospital is 25% within three postoperative days. Hudetz et al27 found that ketamine was associated with a 28% (95% CI 8% to 46%) absolute risk reduction in delirium (from a baseline incidence of 31%). A 28% reduction is likely to be an overoptimistic effect size for designing a pragmatic study; 10% is more realistic as the most optimistic effect size and remains consistent with the CI for the effect size found by Hudetz et al.27 Assuming a two-sided type I error rate of 5%, a sample size of 600 will give greater than 80% power to detect a decrease in the incidence of delirium from 25% to 15% with ketamine. On the other hand, we consider the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) or effect size to be 2%, which corresponds to a number needed to treat 50 surgical patients to prevent one episode of delirium. The rationale for the low MCID is that delirium is a serious postoperative complication that is associated with increased mortality and the proposed intervention (low-dose ketamine) is safe, inexpensive and not likely to have adverse effects.

There are two specific issues to clarify in this study: (1) the likely effect size with ketamine and (2) the optimal ketamine dose. Ketamine might increase delirium, decrease delirium or have no impact on delirium. If ketamine increases delirium, it is more likely to increase delirium at a higher dose (1 mg/kg). If ketamine decreases delirium, it might have a dose–response effect—less delirium at the higher ketamine dose (1 mg/kg). We anticipate that ketamine will decrease pain in a dose-dependent manner—1 mg/kg will be superior to 0.5 mg/kg. Accrual of 200 patients to each dose of ketamine along with a placebo arm will allow a more robust assessment of the dose–response efficacy for postoperative analgesia than previous studies with fewer numbers. In general, the higher ketamine dose might have more side effects. As such, this trial might inform whether the higher ketamine dose can be used, in view of its possibly superior analgesia, with a potential benefit in relation to delirium and without excessive side effects. The dosage determination going forward will depend on the observed incidence of delirium with each dose, analgesia efficacy with each dose and side effect profile with each dose. The proposed design for the study is shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Patient allocation

| Group | N |

|---|---|

| Placebo | 200 patients |

| Ketamine low dose (0.5 mg/kg) | 200 patients |

| Ketamine moderate dose (1 mg/kg) | 200 patients |

With this approach, we believe that this study will clearly inform whether it is indicated, both in terms of efficacy as well as feasibility, to pursue a larger study. The purpose of the larger study (PODCAST2) will be to determine definitively whether ketamine is associated with a reduction in delirium (and pain) in high-risk older surgical patients, without incurring an increase in side effects. As the main effect evaluated will be to determine whether ketamine decreases delirium, table 3 provides a useful guide for the potential findings of the current study with their implications.

Table 3.

Potential findings of PODCAST

| Delirium incidence in placebo groups (N=200) (%) | Delirium incidence in ketamine groups (N=400) (%) | Effect size (reduction in delirium with ketamine) (%) | 95% CI for effect size (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 (N=50) | 25 (N=100) | 0 | −7.6 to 7.1 |

| Implication: consider pursuing a larger study only if pain is decreased in ketamine groups, and there is no increase in side effects | |||

| 25 (N=50) | 22.5 (N=90) | 2.5 | −4.5 to 10.0 |

| Implication: although the point estimate is >2% (MCID), a 9500 patient study would be required to clarify more precisely the effectiveness of ketamine in preventing delirium. Other outcomes in the study (eg, pain reduction and side effects) would inform the approach | |||

| 25 (N=50) | 20 (N=80) | 5 | −1.9 to 12.4 |

| Implication: pursue a larger study with approximately 2500 patients to clarify more precisely the effect of ketamine on preventing delirium | |||

| 25 (N=50) | 17.5 (N=70) | 7.5 | 0.7 to 14.8 |

| Implication: pursue a larger study (approximately 1200 patients) to clarify whether effect size >2% (MCID) and to define it more precisely | |||

| 25 | 15 | 10 | 3.3 to 17.1 |

| Implication: for a main effect, a lower bound of CI >2% (MCID). Ketamine's benefit in decreasing delirium is very likely, but a larger study (approximately 1200 patients) would define its effect more precisely | |||

PODCAST, Prevention of Delirium and Complications Associated with Surgical Treatments; MCID, minimum clinically important difference.

Recruitment

This clinical trial will be conducted at Washington University in St Louis and other sites. Our research team has conducted large randomised controlled trials, which enrolled (approximately) 2000 patients over 14 months in the B-unaware trial,60 6000 patients over 26 months in the BAG-RECALL trial59 and 22 000 patients over 24 months in the Michigan Awareness Control Study.61 On the basis of the inclusion criteria and the number of eligible surgical patients, we estimate that 1 year will be sufficient for patient enrolment to the proposed trial, and a further 1 year for data analysis.

Allocation

Participants will be block randomised by the hospital pharmacy departments in groups of 15 (1:1:1 ratio—0.5 mg/kg ketamine: 1 mg/kg ketamine: placebo), stratified by site, in order to keep the randomisation balanced and the groups more homogeneous. The outcome of this random assignment will be concealed from the study team, and all study participants and trial staff will be blinded to the randomisation. Codes will be held by the hospital pharmacies and they will dispense medication. Randomisation codes will remain concealed until the primary analysis is completed. Prepared syringes of either placebo or ketamine will be directly delivered to the operating room in which surgery of the consenting patient will take place as soon as the research team informs the pharmacy about the patient going to the operating room for surgery.

Data analysis and management

Data analysis for this investigation will require comparisons of patient outcomes (eg, delirium, pain, length of stay, adverse events) in the three study groups to assess for significant differences among ketamine doses (placebo, 0.5 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg). For proportions and categorical outcomes, such as incident delirium, we will use the χ2 test (or Fisher's exact test in the case of sparse data) to compare proportions across the three groups and the Cochran-Armitage test to test for dose–response trends. For continuous outcomes, such as visual analogue pain scores and opioid consumption, we will use repeated-measures analysis of variance tests to detect the main effects. The Tukey post hoc test will also be run on all significant interactions to determine differences between individual and combined groups (eg, placebo vs combined ketamine groups; 0.5 vs 1 mg/kg ketamine). For multivariate analyses, we will apply the Cox proportional hazards model for recurrent events to investigate the effects of low doses of intraoperative ketamine on delirium by comparing its occurrence and timing across the study groups. We will also model the number of postoperative delirium incidents using a Poisson hurdle regression to find out the difference in the proportion of patients with and without delirium, and for those who experience delirium, the difference in its recurrence. Both models (Cox proportional hazards and hurdle model) will account for differences in ketamine effectiveness in cardiac versus non-cardiac surgery by including interaction terms for ketamine dose and cardiac surgery status, while adjusting for other influential variables. We will also use mixed-effects regression models to assess differences among subgroups in continuous outcome variables over time (eg, postoperative pain scores and opioid consumption). These models will likewise account for interactions between ketamine dose and cardiac surgery status. All statistical testing will be two-sided, and p values <0.05 will be regarded as significant. No interim analyses are planned. Appropriate adjustment will be made for multiple analyses.

The Division of Biostatistics Informatics Core at Washington University will be used as a central location for data processing and management. Washington University belongs to a consortium of institutional partners that works to maintain a software toolset and workflow methodology for electronic collection and management of research and clinical trial data. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) data collection projects rely on a thorough study-specific data dictionary defined in an iterative self-documenting process by all members of the research team with planning assistance from the Division of Biostatistics Informatics Core. The iterative development and testing process results in a well-planned data collection strategy for individual studies. REDCap servers are securely housed in an on-site limited access data centre managed by the Division of Biostatistics at Washington University. All web-based information transmission is encrypted. The data are all stored on a private firewall protected network. All users are given individual user IDs and passwords and their access is restricted on a role-specific basis. REDCap was developed specifically around HIPAA-Security guidelines and is implemented and maintained according to the Washington University guidelines. REDCap currently supports >500 academic/non-profit consortium partners on six continents and 38 800 research end users.62

Monitoring

The research team will monitor the study for adverse events. All serious adverse events will be reported to the Institutional Review Board (IRB) according to the IRB stipulations. The monitoring plan for this study is appropriate for the planned pragmatic trial. As an anaesthetic drug, ketamine has an excellent safety profile and record. In particular, low-dose ketamine (0.5 or 1 mg/kg) administered prior to surgical incision is unlikely to be associated with major adverse events, and even minor side effects manifesting after induction of anaesthesia and the start of surgery are improbable.37 38 63

The PODCAST trial will have an appropriate data and safety monitoring plan for a low-risk clinical trial. There will be a charter to guide the functions of the Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB), and the DSMB will produce reports in accordance with the NIH guidelines. The DSMB will provide independent oversight of the PODCAST trial and will review the general conduct of the trial as well as study data for participant safety.64 The DSMB will comprise independent, multidisciplinary experts who will make recommendations regarding the continuation, modification or termination of the trial.65 The members will have the requisite expertise to examine accumulating data, to protect the integrity of the clinical experiments in which the patients have consented to participate and to assure the regulatory bodies and the public (and possibly funding agencies) that conflicts of interest do not compromise either patient safety or trial integrity.66 There will be no prespecified interim analysis given the size of this study; frequent analyses might increase the likelihood of bias.64 There will be a provision for early stoppage for safety concerns, but not for efficacy or for futility.64 Trials that stop early for benefit show implausibly large treatment effects, particularly when the number of events is small.67 Truncated trials have been associated with greater effect sizes than trials not stopped early, independent of the presence of statistical stopping rules.68

All members of the DSMB will be at the Washington University site. Local investigators at all participating sites will report serious adverse events, or unanticipated problems involving risks to participants or others, to their IRB and to the principal investigator (PI) of the study at Washington University. If such problems are considered to be related to the trial, then they will also be reported to IRBs at other participating sites and to the chairperson of the DSMB. The members of the DSMB will have no direct involvement in the conduct of the PODCAST trial. Neither will they have financial, proprietary or professional conflicts of interest, which may affect the impartial, independent decision-making responsibilities of the DSMB.64 65 Letters of invitation to prospective DSMB members will include the following: “Acceptance of this invitation to serve on the PODCAST DSMB confirms that I do not have any financial or other interest with any of the collaborating or competing pharmaceutical firms or other organizations involved in the study that constitute a potential conflict of interest.” All DSMB members will sign a Conflict of Interest Certification to confirm that no conflict exists. There will be between three and eight people on the DSMB, in order to optimise performance.69 The DSMB will be advisory rather than executive on the basis that it is the PODCAST trial investigators who are ultimately responsible for the conduct of the trial.69

The risks associated with this study are low. There is a rare risk of breach of confidentiality. In contrast to other anaesthetics, protective reflexes such as coughing and swallowing are maintained with low-dose ketamine. The 2005 package insert for ketamine reports the induction dose for anaesthesia as follows: the initial dose of ketamine administered intravenously may range from 1 to 4.5 mg/kg. The average amount required to produce 5–10 min of surgical anaesthesia has been 2 mg/kg. The short-term side effects of ketamine at higher doses (>1–2 mg/kg) than the dosages proposed for this study (0.5 or 1 mg/kg) include tachycardia, nystagmus, hypersalivation, euphoria, emergence reactions, hallucinations and nightmares.70 It is possible, but very unlikely, that low-dose ketamine (0.5 or 1 mg/kg) administered just after induction of anaesthesia or administration of sedative medications will cause these side effects.37 38 63 Emergence reactions, hallucinations and nightmares are more common in younger patients receiving ketamine. In published studies on low-dose ketamine (0.25–1 mg/kg) administered during general anaesthesia, side effects have generally not been found.37 The main side effects that might occur are nightmares and hallucinations. Other neuropsychiatric side effects might occur, most likely within the first 24 h after surgery, and will be determined from patient interviews. The incidence of these side effects in this patient population is currently unknown, and thus side effects will be reported separately and jointly. Meta-analysis suggests that ketamine might be associated with an increase in neurological and psychiatric side effects from approximately 5% to 7.5%. This study will be >80% powered to detect an increase in side effects from 5% to 12% and 20% powered to detect an increase in side effects from approximately 5% to 7.5%. As part of the informed consent process for this study, patients will be informed of the rare risks and will be asked about them after their surgery. In the unlikely event that serious side effects occur, they will be documented and also reported to the human research protection office and to the study's DSMB. Participants will not incur any study-related expenses, and nor will they be financially compensated for their participation.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval and consent

The PODCAST trial has been approved by the IRBs of the PIs’ home institutions (Washington University, St Louis and University of Michigan, Ann Arbor). IRB approval has also been obtained at some of the participating sites (Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India; University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada; Weill Medical College, Cornell University, New York City; Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee) and is ongoing at other sites. Recruitment began in February 2014 and will continue until the end of 2016. Potential participants will be approached for enrolment by a member of the research team who will explain the purpose of the study and written informed consent will be obtained for all participants. Patients may choose not to participate in this study and there will be no penalty in terms of the care that they receive.

Confidentiality

Necessary protected health information will only be shared with members of the research team. To help protect confidentiality, research charts will be stored in a locked cabinet inside the locked research office. Electronic data and demographic information will also be kept in a password-protected electronic database stored on the departmental network drive and only accessible via password-protected departmental computers. A member of the research team will enter this information. Code numbers, rather than names, will appear on any data and documents used for evaluation or statistical analyses.

Dissemination

Dissemination plans include presentations at local, national and international scientific conferences. There are no publication restrictions and no professional writers will be involved in the generation of the manuscript.

Conclusions

In the next four decades, the US population over the age of 60 is predicted to double to more than 80 million individuals. The ageing population often requires surgery, which can be frequently complicated by postoperative pain and delirium. Delirium is defined as an acute brain dysfunction that presents as fluctuating levels of inattention and disordered thinking, and has been reported to affect up to 70% of surgical patients older than 60. Likewise, severe postoperative pain continues to affect a large proportion of surgical patients, especially the elderly, and is another major contributor to delirium. Unfortunately, opioid medications, the current standard for analgesia, can themselves lead to delirium and other adverse consequences. Clinicians therefore face the paradox that both pain and the mainstay treatment of pain can lead to delirium. Although causal relationships have not been established, postoperative delirium is associated with increased ICU and hospital stay, persistent cognitive decline and increased mortality rate. What is needed is a therapeutic intervention that can both attenuate pain and decrease the occurrence of delirium. Mounting evidence suggests that the intraoperative administration of low-dose (ie, subanaesthetic) ketamine, an anaesthetic drug that has been in common use for 50 years, prevents delirium, lessens the severity of postoperative pain, and has an opioid-sparing effect. These multiple beneficial effects have been attributed to ketamine's anti-inflammatory and antiexcitotoxic actions. Despite these benefits, low-dose intraoperative ketamine currently does not enjoy widespread adoption, primarily because clinicians are concerned that the psychoactive properties of ketamine might compromise postoperative cognition. The PODCAST randomised controlled trial intends to address a gap in the field through an international multicentre study that tests the effectiveness of ketamine in reducing both delirium and pain in surgical patients older than 60.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

PODCAST research group: A Alexander, R Arora, J Bang, M Bottros, A Cai, BM Choi, IC Choi, ME Davis, R Downey, D Emmert, M Engoren, SD Gandhi, L Girling, N Hanson, Z Iqbal, A Jayant, E Lenze, M Maile, J McVagh, J Neal, S Oskar, KM Patterson, E Rogers, B Tellor, T Wildes, A Villafranca, H Yulico.

Footnotes

Collaborators: SW Ku; BM Choi; IC Choi; J Bang; E Rogers; SD Gandhi; R Downey; Z Iqbal; KM Patterson; ME Davis; H Yulico; S Oskar; J Aveek; A Villafranca; R Arora; J McVagh; L Girling; M Engoren; M Maile; A Alexander; J Neal; N Hanson; D Emmert; T Wildes; M Bottros; E Lenze; B Tellor; A Cai.

Contributors: MSA and GAM are the primary authors of the PODCAST protocol. Their contributions include drafting and editing the protocol, conceptualising the study design, and organising conduct across all sites. BAF contributed to the PODCAST trial by editing the protocol, conceptualising the study design, creating the electronic database REDCap used for data collection and coauthoring a manual of operations for study conduct. HRM contributed to the PODCAST trial by editing the protocol, coauthoring the manual of operations, recruiting patients for enrolment, collecting data and coordinating the study across all sites. MRM contributed to the PODCAST trial by coauthoring a manual of operations, recruiting patients for enrolment and collecting data. KEE contributed to the PODCAST trial by editing the protocol, conceptualising the study design and coauthoring a manual of operations. YC contributed to the PODCAST trial by editing the protocol and conceptualising the study design. ABA contributed to the PODCAST trial by editing the protocol and conceptualising the study design, including the statistical modelling of the study. SKI contributed to the PODCAST trial by training investigators to perform delirium assessments and conceptualising the study design. SC, RJD, HPG, GN, JAH, EJ, HK, PSP, KP, RP, RAV and VKA contributed to the PODCAST trial by editing the study protocol, conceptualising the study design, recruiting participants and collecting data. All authors including MSA, GAM, BAF, HRM, MRM, KEE, YC, ABA, SKI, RAV, HPG, JAH, KP, PSP, VKA, RP, EJ, HPG, HK, RJD and SC have critically revised the PODCAST protocol and approved the final version. All authors agree to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of all aspects of the PODCAST trial.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: SW Ku, BM Choi, IC Choi, J Bang, E Rogers, SD Gandhi, R Downey, Z Iqbal, KM Patterson, ME Davis, H Yulico, S Oskar, J Aveek, A Villafranca, R Arora, J McVagh, L Girling, M Engoren, M Maile, A Alexander, J Neal, N Hanson, D Emmert, T Wildes, M Bottros, E Lenze, B Tellor, and A Cai

References

- 1.Whitlock EL, Vannucci A, Avidan MS. Postoperative delirium. Minerva Anestesiol 2011;77:448–56 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, et al. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:27–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottesman RF, Grega MA, Bailey MM, et al. Delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery and late mortality. Ann Neurol 2010;67:338–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koster S, Hensens AG, Schuurmans MJ, et al. Consequences of delirium after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:705–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kat MG, Vreeswijk R, de Jonghe JF, et al. Long-term cognitive outcome of delirium in elderly hip surgery patients. A prospective matched controlled study over two and a half years. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;26:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bickel H, Gradinger R, Kochs E, et al. High risk of cognitive and functional decline after postoperative delirium. A three-year prospective study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;26:26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radtke FM, Franck M, Lorenz M, et al. Remifentanil reduces the incidence of post-operative delirium. J Int Med Res 2010;38:1225–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandharipande P, Cotton BA, Shintani A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for development of delirium in surgical and trauma intensive care unit patients. J Trauma 2008;65:34–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weed HG, Lutman CV, Young DC, et al. Preoperative identification of patients at risk for delirium after major head and neck cancer surgery. Laryngoscope 1995;105:1066–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kazmierski J, Kowman M, Banach M, et al. Incidence and predictors of delirium after cardiac surgery: results from The IPDACS Study. J Psychosom Res 2010;69:179–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudolph JL, Inouye SK, Jones RN, et al. Delirium: an independent predictor of functional decline after cardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:643–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, et al. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med 2012;367:30–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA 1994;271:134–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider F, Bohner H, Habel U, et al. Risk factors for postoperative delirium in vascular surgery. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2002;24:28–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohner H, Hummel TC, Habel U, et al. Predicting delirium after vascular surgery: a model based on pre- and intraoperative data. Ann Surg 2003;238:149–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benoit AG, Campbell BI, Tanner JR, et al. Risk factors and prevalence of perioperative cognitive dysfunction in abdominal aneurysm patients. J Vasc Surg 2005;42:884–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher BW, Flowerdew G. A simple model for predicting postoperative delirium in older patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:175–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Michaels M, et al. Delirium is independently associated with poor functional recovery after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:618–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee KH, Ha YC, Lee YK, et al. Frequency, risk factors, and prognosis of prolonged delirium in elderly patients after hip fracture surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011;469:2612–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1157–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudetz JA, Pagel PS. Neuroprotection by ketamine: a review of the experimental and clinical evidence. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2010;24:131–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Jing W, Hang YN. Glutamate-induced c-Jun expression in neuronal PC12 cells: the effects of ketamine and propofol. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2008;20:124–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Shu S, Bayliss DA. HCN1 channel subunits are a molecular substrate for hypnotic actions of ketamine. J Neurosci 2009;29:600–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis AS, Chetkovich DM. HCN channels in behavior and neurological disease: too hyper or not active enough? Mol Cell Neurosci 2011;46:357–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho HJ, Staikopoulos V, Furness JB, et al. Inflammation-induced increase in hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated channel protein in trigeminal ganglion neurons and the effect of buprenorphine. Neuroscience 2009;162:453–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emery EC, Young GT, Berrocoso EM, et al. HCN2 ion channels play a central role in inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Science 2011;333:1462–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudetz JA, Patterson KM, Iqbal Z, et al. Ketamine attenuates delirium after cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2009;23:651–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudetz JA, Iqbal Z, Gandhi SD, et al. Ketamine attenuates post-operative cognitive dysfunction after cardiac surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:864–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartoc C, Frumento RJ, Jalbout M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study assessing the anti-inflammatory effects of ketamine in cardiac surgical patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2006;20:217–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fine J, Finestone SC. Sensory disturbances following ketamine anesthesia: recurrent hallucinations. Anesth Analg 1973;52:428–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lilburn JK, Dundee JW, Nair SG, et al. Ketamine sequelae. Evaluation of the ability of various premedicants to attenuate its psychic actions. Anaesthesia 1978;33:307–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips DM. JCAHO pain management standards are unveiled. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. JAMA 2000;284:428–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brennan F, Carr DB, Cousins M. Pain management: a fundamental human right. Anesth Analg 2007;105:205–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cousins MJ, Lynch ME. The Declaration Montreal: access to pain management is a fundamental human right. Pain 2011;152:2673–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dolin SJ, Cashman JN, Bland JM. Effectiveness of acute postoperative pain management: I. Evidence from published data. Br J Anaesth 2002;89:409–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macrae WA. Chronic post-surgical pain: 10 years on. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elia N, Tramer MR. Ketamine and postoperative pain—a quantitative systematic review of randomised trials. Pain 2005;113:61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell RF, Dahl JB, Moore RA, et al. Perioperative ketamine for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD004603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laskowski K, Stirling A, McKay WP, et al. A systematic review of intravenous ketamine for postoperative analgesia. Can J Anaesth 2011;58:911–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan MT, Wan AC, Gin T, et al. Chronic postsurgical pain after nitrous oxide anesthesia. Pain 2011;152:2514–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Remerand F, Le Tendre C, Baud A, et al. The early and delayed analgesic effects of ketamine after total hip arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind study. Anesth Analg 2009;109:1963–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, et al. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ 2008;337:a2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Treweek S, Zwarenstein M. Making trials matter: pragmatic and explanatory trials and the problem of applicability. Trials 2009;10:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology 2012;116:248–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management; American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Practice guidelines for chronic pain management: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Chronic Pain Management and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Anesthesiology 2010;112:810–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:e1–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wade DT, Collin C. The Barthel ADL Index: a standard measure of physical disability? Int Disabil Stud 1988;10:64–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brahler E. Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013;35:551–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology 2008;108:812–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 1990;113:941–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA 2001;286:2703–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med 2001;29:1370–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luetz A, Heymann A, Radtke FM, et al. Different assessment tools for intensive care unit delirium: which score to use? Crit Care Med 2010;38:409–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Plaschke K, von Haken R, Scholz M, et al. Comparison of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) with the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) for delirium in critical care patients gives high agreement rate(s). Intensive Care Med 2008;34:431–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steis MR, Evans L, Hirschman KB, et al. Screening for delirium using family caregivers: convergent validity of the Family Confusion Assessment Method and interviewer-rated Confusion Assessment Method. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:2121–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Payen JF, Bru O, Bosson JL, et al. Assessing pain in critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale. Crit Care Med 2001;29:2258–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chanques G, Payen JF, Mercier G, et al. Assessing pain in non-intubated critically ill patients unable to self report: an adaptation of the Behavioral Pain Scale. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:2060–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Avidan MS, Jacobsohn E, Glick D, et al. Prevention of intraoperative awareness in a high-risk surgical population. N Engl J Med 2011;365:591–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Avidan MS, Zhang L, Burnside BA, et al. Anesthesia awareness and the bispectral index. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1097–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mashour GA, Shanks A, Tremper KK, et al. Prevention of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall in an unselected surgical population: a randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Anesthesiology 2012;117:717–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nesher N, Serovian I, Marouani N, et al. Ketamine spares morphine consumption after transthoracic lung and heart surgery without adverse hemodynamic effects. Pharmacol Res 2008;58:38–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tharmanathan P, Calvert M, Hampton J, et al. The use of interim data and Data Monitoring Committee recommendations in randomized controlled trial reports: frequency, implications and potential sources of bias. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fleming TR, DeMets DL. Monitoring of clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Control Clin Trials 1993;14:183–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith MA, Ungerleider RS, Korn EL, et al. Role of independent data-monitoring committees in randomized clinical trials sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:2736–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Montori VM, Devereaux PJ, Adhikari NK, et al. Randomized trials stopped early for benefit: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;294:2203–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bassler D, Briel M, Montori VM, et al. Stopping randomized trials early for benefit and estimation of treatment effects: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA 2010;303:1180–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grant AM, Altman DG, Babiker AB, et al. Issues in data monitoring and interim analysis of trials. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:1–238, iii–iv [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Strayer RJ, Nelson LS. Adverse events associated with ketamine for procedural sedation in adults. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26:985–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.