Abstract

Objectives

Although B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and highly sensitive cardiac troponin T (cTnT) are useful for the evaluation of clinical features in various cardiovascular diseases, there are comparatively few data regarding the utility of these parameters in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). The goal of this study was to assess the association between BNP, cTnT and clinical parameters in patients with HOCM.

Design

Cross-sectional survey

Settings

The relationship between BNP, cTnT and clinical end points and echocardiographic data was investigated.

Participants

This study included 102 consecutive outpatients with HOCM who were clinically stable.

Results

BNP was significantly associated with both maximum left ventricular (LV) wall thickness (r=0.28; p=0.003), and septal peak early transmitral filling velocity/peak early diastolic mitral annulus velocity (r=0.51; p=0.0001). No statistically significant associations were seen between cTnT and any echocardiographic parameters, but the presence of atrial fibrillation (AF) was associated with a high level of cTnT (p=0.01).

Conclusions

BNP is useful for monitoring clinical parameters and as a reflection of both LV systolic/diastolic function and increased LV pressure in patients with HOCM. A high level of serum cTnT is associated with the presence of AF.

Keywords: CARDIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a first study to explore the relationship between B-type natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and clinical features in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) and to demonstrate that increased cTnT levels are associated with the presence of atrial fibrillation in patients with HOCM.

The patient sample size is small due to the relative rarity of this disease.

The echocardiography study was independently evaluated by two examiners.

Introduction

Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) is a type of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) characterised by dynamic left ventricular (LV) outflow-tract obstruction caused by asymmetrical septal hypertrophy. Depending in part on the site and extent of cardiac hypertrophy, patients with HOCM can develop several abnormalities, such as LV outflow obstruction, diastolic dysfunction, myocardial ischaemia and mitral regurgitation. Therefore, the structural and functional abnormalities associated with HOCM can produce a variety of symptoms, including fatigue, dyspnoea, chest pain, palpitations, presyncope or syncope.

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels are elevated in proportion to the severity of LV diastolic and systolic dysfunction.1–3 Previous studies have demonstrated that BNP is useful for the prediction of outcomes in patients with HCM, hypertensive heart disease and aortic stenosis,4–10 indicating the significance of BNP elevation in heart disease characterised by LV hypertrophy. Highly sensitive cardiac troponin T (cTnT) is another cardiac marker that can detect myocardial damage. Although cTnT is a strong predictor of adverse outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome,11 12 stable coronary artery disease,13 14 congestive heart failure15–17 and HCM, including hypertrophic non-obstructive cardiomyopathy,18 19 there are comparatively few data regarding the utility of cTnT in only HOCM. Further, it is not clear whether BNP and/or cTnT are useful for monitoring the clinical status of patients with only HOCM. Therefore, the goal of this study was to assess the relationship between BNP, cTnT and clinical parameters in patients with HOCM.

Methods

Study design and participant recruitment

We analysed consecutive outpatients with HOCM who were clinically stable and who visited the ‘HOCM clinic’ at Nippon Medical School Hospital for periodical follow-up between January 2011 and June 2012. The diagnosis of HOCM was based on typical clinical, ECG and haemodynamic features with echocardiographic demonstration of a non-dilated, asymmetrically hypertrophied LV in the absence of other cardiac or systemic diseases that can produce LV hypertrophy. Patients with significant organic coronary stenosis, valvular heart disease, systemic hypertension, concomitant neoplasm, infection, connective tissue disease or diabetes mellitus were excluded from study. A complete history and clinical examination was performed along with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class assessment, presence of atrial fibrillation (AF), blood examination and echocardiography.

Echocardiography study

Two-dimensional (2D), M-mode and Doppler echocardiographic studies were performed with PHILIPS IE 33 or GE Vivid E 9 ultrasound systems on the same day when serum cTnT and BNP were measured. Wall thickness (IVST, interventricular septal thickness; PWT, posterior wall thickness; and MWT, maximum LV wall thickness), cavity size (LVEDD, LV end-diastolic diameter; and LVESD, LV end-systolic diameter), LV diastolic dysfunction (E/Ea, peak early transmitral filling velocity/peak early diastolic mitral annulus velocity on tissue Doppler imaging), maximum pressure gradient (Max PG, maximum peak gradient in the LV), tricuspid regurgitation peak gradient, and wall motion were measured from M-mode and 2D images. MWT was defined as the greatest thickness in any single segment. LV diastolic function was assessed by septal and lateral E/Ea. The ventricular volume and ejection fraction were computed using the biapical Simpson's rule.

Measurement of cTnT and BNP

Peripheral blood samples were collected for measurement of serum BNP and cTnT at the same time as other examinations. Serum BNP and cTnT were measured with an AIA-2000ST analyzer (TOSOH, Tokyo, Japan) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The assay detection limit was ≥0.003 ng/mL. Patients were divided into low or high BNP groups and into low and high cTnT groups according to previously reported cut-off points (200 pg/mL for BNP and 0.014 ng/mL for cTnT).10 19

Statistical methods

Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The normal distributed continuous variables are shown as means±SD, and non-parametrically distributed variables are shown as medians (IQR). Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percentages). Correlation between two continuous variables was examined by Pearson's test (if relevant by Spearman's test). Logistic regression analyses were performed with the presence/absence of elevated cTnT or BNP levels as the dependent variable (cTnT cut-off point ≥0.014 ng/mL, BNP cut-off point ≥200 pg/mL) and different clinical factors as covariables. Multiple regression analyses of the relationship between cTnT or BNP and study variables were performed in order to detect clinical characteristics related to these markers after adjustment for inter-relationship among study variables. A two-sided probability value of p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. JMP (V.9.0.3, North Carolina, USA) was used for analysis.

Results

There were 104 patients who visited the ‘HOCM clinic’ during the examination period, of which two patients were excluded due to the absence of echocardiographic data. Therefore, the study population consisted of 102 consecutive patients who underwent complete clinical, echocardiographic, and serum-marker assessment. Baseline characteristics of the 102 patients are shown in table 1. There were 84 patients (82.3%) with LV outflow obstruction, 13 patients (12.7%) with mid-cavity obstruction and 5 patients (4.9%) with apical obstruction. Serum BNP ranged from 33.6 to 2593 pg/mL (mean, 286.5±334 pg/mL; median, 174.4 pg/mL). Twenty-four patients (23.5%) had a BNP level above the cut-off point (400 pg/mL), including three patients (2.9%) with a level ≥1000 pg/mL. Serum cTnT ranged from 0.003 to 0.09 ng/mL (mean, 0.015±0.015 ng/mL; median, 0.011 ng/mL). Eighty-six patients (84.3%) had a cTnT level above the detection limit of assay (0.003 ng/mL), including 37 patients (36.2%) with a level ≥0.014 ng/mL and 5 patients (4.9%) with a level ≥0.05 ng/mL. There was no significant association between BNP and cTnT levels (r=0.06, p=0.10, by Spearman's rank correlation test).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for the study samples

| Age (years) | 67.1±11.7 |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 71 (69.6) |

| Types of obstruction, (%) | |

| LVOT obstruction | 84 (82.3) |

| Mid-ventricular obstruction | 13 (12.7) |

| Apical obstruction | 5 (5.0) |

| NYHA functional class, n (%) | |

| I | 62 (60.8) |

| II | 39 (38.3) |

| III-IV | 1 (0.9) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 76 (74.5) |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.732) | 75.1±26.2 |

| Echocardiographic data | |

| LVEF (%) | 73.5±8.0 |

| IVST (mm) | 14.7±4.9 |

| PWT (mm) | 10.2±1.8 |

| MWT (mm) | 16.2±4.0 |

| LV end-diastolic dimension (mm) | 43.7±5.6 |

| Left atrial dimension (mm) | 43.5±8.2 |

| Septal E/Ea | 16.5±8.9 |

| Lateral E/Ea | 12.0±5.6 |

| LV pressure gradient (mm Hg) | 42.6±40.4 |

| TR pressure gradient (mm Hg) | 27.6±8.5 |

| Medications, n (%) | |

| β-blocker | 86 (86.0) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 38 (38.3) |

| Cibenzoline | 65 (65.6) |

Data are expressed as mean±SD or number of the patients (percentage).E/Ea, peak early transmitral filling velocity/peak early diastolic mitral annulus velocity on tissue Doppler imaging; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IVST, interventricular septal thickness; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, LV ejection fraction; LVOT, LV outflow tract; MWT, maximum LV wall thickness; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PWT, posterior wall thickness; TR, tricuspid regurgitation.

Relationship between biomarkers, clinical features and echocardiographic characteristics

BNP was significantly associated with IVST (r=0.31; p=0.001), MWT (r=0.28; p=0.003), septal E/Ea (r=0.51; p=0.0001) and lateral E/Ea (r=0.41; p=0.0001; table 2). BNP was negatively associated with LVEDD (r=−0.39; p=0.001) and LVESD (r=−0.20; p=0.04; table 2). Patients were divided into two groups according to BNP level: the low BNP group (BNP <200 pg/mL) and the high BNP group (BNP ≥200 pg/mL; table 3). More patients had NYHA functional class II in the high BNP group than in the low BNP group, and LVEDD and lateral E/Ea were greater in the high BNP group than in the low BNP group (table 3).

Table 2.

Associations between BNP or cTnT and clinical parameters

| BNP |

cTnT |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r Value | p Value | r Value | p Value | |

| Age | −0.02 | 0.81 | 0.08 | 0.38 |

| IVST | 0.31 | 0.0013 | 0.03 | 0.70 |

| PWT | 0.014 | 0.88 | 0.08 | 0.40 |

| MWT | 0.28 | 0.0039 | 0.15 | 0.11 |

| LAD | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.06 |

| LVEDD | −0.39 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.24 |

| LVESD | −0.20 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.09 |

| LVEF | −0.10 | 0.28 | −0.12 | 0.20 |

| Septal E/Ea | 0.51 | 0.0001 | 0.06 | 0.51 |

| Lateral E/Ea | 0.41 | 0.0001 | 0.10 | 0.33 |

| Max PG | 0.06 | 0.52 | −0.10 | 0.30 |

| TRPG | 0.08 | 0.43 | −0.005 | 0.96 |

BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; E/Ea, peak early transmitral filling velocity/peak early diastolic mitral annulus velocity on tissue Doppler imaging; IVST, interventricular septal thickness; LAD, left atrial diameter; LV, left ventricular; LVEDD, LV end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, LV ejection fraction; LVESD, LV end-systolic diameter; Max PG, maximum peak gradient in the left ventricle; MWT, maximum LV wall thickness; PWT, posterior wall thickness; TRPG, tricuspid regurgitation peak gradient.

Table 3.

BNP, cTnT and characteristics of the patients

| BNP (pg/mL) |

cTnT (ng/mL) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNP <200 | BNP ≥200 | p Value | cTnT <0.014 | cTnT ≥0.014 | p Value | |

| Age, years | 66.9±10.7 | 67.4±12.7 | 0.8 | 66.5±11.9 | 68.4±11.3 | 0.4 |

| Female, % | 33 (63.4) | 38 (76.0) | 0.19 | 45 (69.2) | 26 (70.2) | 1.00 |

| NYHA class, % | 14 (26.9) | 24 (48.0) | 0.04 | 24 (36.9) | 14 (37.8) | 1.0 |

| AF, % | 9 (17.3) | 17 (34.0) | 0.06 | 11 (16.9) | 15 (40.5) | 0.01 |

| eGFR | 75.1±26.5 | 74.9±25.7 | 1.0 | 70.8±26.9 | 77.5±25.7 | 0.21 |

| MWT | 15.6±3.5 | 16.9±4.4 | 0.09 | 16.2±4.5 | 16.2±3.1 | 0.9 |

| LVEDD | 45.2±5.6 | 42.0±5.1 | 0.003 | 43.5±5.7 | 44.0±5.5 | 0.6 |

| LVEF | 74.4±7.6 | 72.5±8.4 | 0.2 | 74.4±6.5 | 71.8±10.1 | 0.12 |

| LAD | 42.2±6.5 | 44.8±9.5 | 0.11 | 42.3±6.3 | 45.5±10.6 | 0.06 |

| Lateral E/Ea | 9.5±3.7 | 14.9±6.2 | 0.002 | 12.3±5.7 | 11.3±5.6 | 0.4 |

| Max PG | 39.0±37.6 | 46.4±43.2 | 0.3 | 45.6±41.3 | 37.1±38.6 | 0.3 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD or number of the patients (percentage).

AF, atrial fibrillation; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; E/Ea, peak early transmitral filling velocity/peak early diastolic mitral annulus velocity on tissue Doppler imaging; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LAD, left atrium diameter; LV, left ventricular; LVEDD, LV end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, LV ejection fraction; Max PG, maximum peak gradient in the LV; MWT, maximum LV wall thickness; NYHA class, New York Heart Association functional class.

There were no statistically significant associations between cTnT and any echocardiographic parameters (table 2). Patients were also divided into two groups according to cTnT level: the low cTnT group (cTnT<0.014 ng/mL) and the high cTnT group (cTnT ≥0.014 ng/mL; table 3). There were no significant differences in age, gender or any echocardiographic parameters between the low cTnT group and the high cTnT group and the presence of AF was significantly higher in the high cTnT group than in the low cTnT group (40.5% vs 16.9%; p=0.01; table 3).

Relationship between AF and cTnT

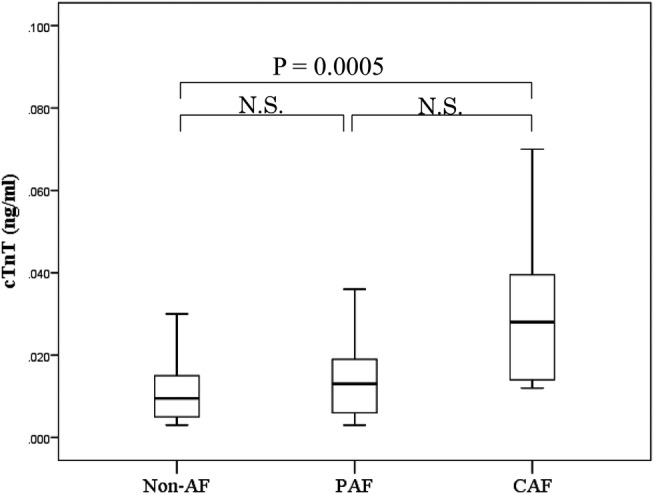

Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed using patient characteristics to investigate factors associated with the presence of AF. As shown in table 4, large left atrium diameter (large LAD ≥50 mm), high BNP (BNP ≥200 pg/mL) and high cTnT (cTnT ≥0.014 ng/mL) were significantly associated with the presence of AF. Multivariate logistic regression analysis using the significant factors obtained within univariate analysis revealed that high LAD and high cTnT were each independent factors for the presence of AF (table 5). Moreover, cTnT levels in patients with persistent AF appeared to be significantly higher than that in patients with paroxysmal AF or in those without AF (median, 0.028 vs 0.013 vs 0.01 ng/mL; p<0.001; figure 1).

Table 4.

Univariate logistic regression analysis of the prevalence of AF versus clinical features

| OR | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) | 0.68 |

| Female | 2.00 (0.80–5.20) | 0.14 |

| NYHA class ≥II | 0.68 (0.26–1.76) | 0.48 |

| MWT | 3.04 (0.07–307.2) | 0.58 |

| LAD ≥50 mm | 8.87 (2.77–31.9) | 0.0002 |

| LVEF | 5.97 (0.47–78.1) | 0.16 |

| E/e’ lateral ≥15 | 1.73 (0.61–4.89) | 0.42 |

| Max PG | 8.47 (1.31–75.5) | 0.23 |

| High BNP | 2.46 (0.97–6.21) | 0.06 |

| High cTnT | 3.34 (1.33–8.42) | 0.01 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; High BNP, high B-type natriuretic peptide level (serum BNP level ≥200 pg/mL); High cTnT, high cardiac troponin T level (serum cTnT level ≥0.014 ng/mL); LAD, left atrium diameter; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, LV ejection fraction; Max PG, maximum peak gradient in the LV; MWT, maximum LV wall thickness; NYHA class, New York Heart Association functional class.

Table 5.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of the prevalence of AF versus clinical features

| OR | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 2.37 | 0.13 |

| High BNP | 2.53 | 0.09 |

| High cTnT | 3.96 | 0.008 |

| LAD ≥50 mm | 6.91 | 0.002 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; High BNP, high B-type natriuretic peptide level; High cTnT, high cardiac troponin T level; LAD, left atrium diameter.

Figure 1.

cTnT levels in patients with HOCM according to the presence, absence, or types of AF. Paroxysmal AF: episodes that come and go, but resolve themselves within seven days; persistent AF: episodes that last beyond seven days; and chronic AF: continuous AF that lasts longer than one year (AF, atrial fibrillation; CAF, chronic atrial fibrillation; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; HOCM, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy; N.S., not significant; PAF, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that BNP was a more useful and reliable biomarker than cTnT for the clinical status of patients with HOCM. The levels were positively associated with various clinical and echocardiographic parameters, including dyspnoea (NYHA functional class), LV filling pressure, diastolic dysfunction (septal and lateral E/Ea), and LV wall thickness (IVST, MWT), whereas high cTnT levels were significantly associated only with the presence of AF. Further, this study demonstrated that BNP levels were significantly and negatively associated with LV volume (LVEDD and LVESD). Finally, cTnT level was independently associated with the presence of AF, and levels of cTnT in patients with persistent AF were significantly higher than those with paroxysmal AF or without AF.

Previous studies have demonstrated that BNP is a useful biomarker of clinical parameters and can predict adverse outcomes in patients with heart failure, cardiomyopathy and ischaemic heart disease.6–9 Previous studies have also reported that serum BNP levels in patient with HCM and hypertension, which typically occurs in the absence of LV cavity volume expansion and in the presence of systolic dysfunction, are independently associated with the presence and magnitude of heart failure symptoms.18–21 Although the present study enrolled only patients with HOCM, the data we obtained were primarily consistent with data from previous studies involving patients with non-obstructive HCM. The present study also demonstrated a positive association between BNP levels and various parameters, including NYHA functional class, septal and lateral E/e’, IVST and MWT. Therefore, these findings serve to extend the principle that serum BNP levels are associated with the presence and magnitude of heart failure symptoms, for non-obstructive HCM in patients with HOCM. Of note, BNP levels were also negatively associated with LVEDD and LVESD, indicating that BNP levels increase in the context of reduced cavity volume and increased end-diastolic pressure. In other words, the present study suggests that LV volume reduction leads to impaired diastolic function and reflects increasing pressure in LV. Prior to the present study, there have been very few investigations of the significance of BNP levels in patients with HOCM.22

In contrast to BNP, serum cTnT levels were not associated with most of the clinical parameters investigated in this study, including diastolic function, LV wall thickness or the magnitude of dyspnoea in HOCM. A previous study reported that the prevalence of elevated cTnT levels (lower limit of detection is 0.01 ng/mL) in the general population was 0.7%.23 Further, serum cTnT levels are higher in patients with HCM than in the general population.19 These observations are consistent with data from the present study, in which the mean cTnT level was 0.015 ng/mL and the prevalence of elevated cTnT levels (equal or above 0.01 ng/dL) was 57.8%. Although prior studies reported that cTnT levels were related to the clinical parameters, such as LV wall thickness, E/e’, or LV outflow tract gradient in patients with HCM (including those with HOCM) and that cTnT was an independent predictor of outcomes,18 19 24 the present study failed to show these relationships. Specifically, the present study found that cTnT elevation was related only to the presence of AF among all clinical parameters investigated.

Elevations of cTnT are related to cardiac remodelling that leads to the development of AF,19 25 26 and Anegawa et al27 reported that the high cTnT level was associated with AF in a general population. However, the relationship between cTnT and AF has not been reported in patients with HCM, including those with HOCM. There are several possible mechanistic explanations for the association between cTnT and the presence of AF. First, modest elevations in cTnT may be caused by leakage from the atrium because of cardiac remodelling, including atrial myocyte death and fibrosis. Second, HOCM is characterised by LV outflow obstruction, diastolic dysfunction, myocardial ischaemia and mitral regurgitation. Thus, the presence of AF in HOCM may potentiate these abnormalities, particularly in regard to myocardial ischaemia. In other words, AF with rapid ventricular response may reduce diastolic filling time, leading to impaired LV filling in patients with HOCM, especially in those with pre-existing diastolic dysfunction. Further, the atrial kick is very important in achieving adequate ventricular filling, and the loss of atrial kick in the context of AF results in decreased LV filling. AF is also often poorly tolerated in patients with HCM and may be associated with significant clinical deterioration.28–30 Therefore, the present findings may indicate that AF might contribute to cardiac ischaemia and progression of cardiac remodelling, including myocyte necrosis. In combination with observations from the present study, this suggests that cTnT may have utility for the detection of ischaemia and cardiac remodelling. By contrast, BNP might be more useful as a reflection of haemodynamic parameters, magnitude of symptoms, and systolic/diastolic function. These may explain why cTnT significantly correlated only with AF. However, several reports have stated that cTnT is related to echocardiographic parameters such as maximum LV wall thickness, and left atrial dimension. Our results showed that cTnT tended to be associated with maximum LV wall thickness and left atrium dimension without statistical significance. This discrepancy could be explained by the small study sample size.

The principal limitation of the present study was its cross-sectional design. Additional limitations include the small patient sample size due to the relative rarity of this disease. Although the number of enrolled patients in the present study might not be sufficient for our results to be generalised, the patient number was equivalent to that in previous studies of patients with HOCM22 and in patients with HCM (including those with HOCM).18 19

To the best of our knowledge, this is a first study to explore the relationship between BNP and cTnT and clinical features in patients with HOCM and to demonstrate that increased cTnT levels are associated with the presence of AF in patients with HOCM. BNP is useful for monitoring clinical parameters and as a reflection of both LV systolic/diastolic function and increased LV pressure in patients with HOCM. Furthermore, a high level of serum cTnT appears to be associated with the presence of AF and may thus be a good marker of cardiac remodelling or ischaemia in patients with HOCM.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SN, HT, JM, DC, MK, KM, KA, MY, MT and WS participated in study concept and design, drafting of the manuscript, administrative, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. WS gave final approval for the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Nippon Medical School Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lukowicz TV, Fischer M, Hense HW, et al. BNP as a marker of diastolic dysfunction in the general population: importance of left ventricular hypertrophy. Eur J Heart Fail 2005;7:525–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahlstrom U. Can natriuretic peptides be used for the diagnosis of diastolic heart failure? Eur J Heart Fail 2004;6:281–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grewal J, McKelvie R, Lonn E, et al. BNP and NT-proBNP predict echocardiographic severity of diastolic dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail 2008;10:252–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maisel AS, Krishnaswamy P, Nowak RM, et al. Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. N Engl J Med 2002;347:161–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis M, Espiner E, Richards G, et al. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide in assessment of acute dyspnoea. Lancet 1994;343:440–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura M, Endo H, Nasu M, et al. Value of plasma B type natriuretic peptide measurement for heart disease screening in a Japanese population. Heart 2002;87:131–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jourdain P, Jondeau G, Funck F, et al. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide-guided therapy to improve outcome in heart failure. The STARS-BNP Multicenter Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1733–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troughton RW, Frampton CM, Yandle TG, et al. Treatment of heart failure guided by plasma aminoterminal brain natriuretic peptide (N-BNP) concentrations. Lancet 2000;355:1126–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCullough PA, Nowak RM, McCord J, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide and clinical judgment in emergency diagnosis of heart failure: analysis from Breathing Not Properly (BNP) Multinational Study. Circulation 2002;106:416–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maron BJ, Tholakanahalli VN, Zenovich AG, et al. Usefulness of B-type natriuretic peptide assay in the assessment of symptomatic state in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2004;109:984–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antman EM, Tanasijevic MJ, Thompson B, et al. Cardiac-specific troponin I levels to predict the risk of mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1342–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heidenreich PA, Alloggiamento T, Melsop K, et al. The prognostic value of troponin in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:478–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsieh BP, Rogers AM, Na B, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of incidental cardiac troponin T elevation in ambulatory patients with stable coronary artery disease: data from the Heart and Soul study. Am Heart J 2009;158:673–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omland T, de Lemos JA, Sabatine MS, et al. A sensitive cardiac troponin T assay in stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2538–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Missov E, Calzolari C, Pau B. Circulating cardiac troponin I in severe congestive heart failure. Circulation 1997;96:2953–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Latini R, Masson S, Anand IS, et al. Prognostic value of very low plasma concentrations of troponin T in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Circulation 2007;116:1242–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.deFilippi CR, de Lemos JA, Christenson RH, et al. Association of serial measures of cardiac troponin T using a sensitive assay with incident heart failure and cardiovascular mortality in older adults. JAMA 2010;304:2494–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubo T, Kitaoka H, Okawa M, et al. Serum cardiac troponin I is related to increased left ventricular wall thickness, left ventricular dysfunction, and male gender in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol 2010;33:E1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno V, Hernandez-Romero D, Vilchez JA, et al. Serum levels of high-sensitivity troponin T: a novel marker for cardiac remodeling in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail 2010;16:950–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasegawa K, Fujiwara H, Doyama K, et al. Ventricular expression of brain natriuretic peptide in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1993;88:372–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanderheyden M, Goethals M, Verstreken S, et al. Wall stress modulates brain natriuretic peptide production in pressure overload cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:2349–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishigaki K, Tomita M, Kagawa K, et al. Marked expression of plasma brain natriuretic peptide is a special feature of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28:1234–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallace TW, Abdullah SM, Drazner MH, et al. Prevalence and determinants of troponin T elevation in the general population. Circulation 2006;113:1958–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubo T, Kitaoka H, Okawa M, et al. Combined measurements of cardiac troponin I and brain natriuretic peptide are useful for predicting adverse outcomes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ J 2011;75:919–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fertin M, Hennache B, Hamon M, et al. Usefulness of serial assessment of B-type natriuretic peptide, troponin I, and C-reactive protein to predict left ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction (from the REVE-2 study). Am J Cardiol 2010;106:1410–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng W, Li B, Kajstura J, et al. Stretch-induced programmed myocyte cell death. J Clin Invest 1995;96:2247–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anegawa T, Kai H, Adachi H, et al. High-sensitive troponin T is associated with atrial fibrillation in a general population. Int J Cardiol 2012;156:98–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson K, Frenneaux MP, Stockins B, et al. Atrial fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a longitudinal study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;15:1279–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olivotto I, Cecchi F, Casey SA, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the clinical course of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2001;104:2517–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stafford WJ, Trohman RG, Bilsker M, et al. Cardiac arrest in an adolescent with atrial fibrillation and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1986;7:701–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.