Abstract

The clinical management of bone defects caused by trauma or nonunion fractures remains a challenge in orthopedic practice due to the poor integration and biocompatibility properties of the scaffold or implant material. In the current work, the osteogenic properties of carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotubes (COOH–SWCNTs) were investigated in vivo and in vitro. When human preosteoblasts and murine embryonic stem cells were cultured on coverslips sprayed with COOH–SWCNTs, accelerated osteogenic differentiation was manifested by increased expression of classical bone marker genes and an increase in the secretion of osteocalcin, in addition to prior mineralization of the extracellular matrix. These results predicated COOH–SWCNTs’ use to further promote osteogenic differentiation in vivo. In contrast, both cell lines had difficulties adhering to multi-walled carbon nanotube-based scaffolds, as shown by scanning electron microscopy. While a suspension of SWCNTs caused cytotoxicity in both cell lines at levels >20 μg/mL, these levels were never achieved by release from sprayed SWCNTs, warranting the approach taken. In vivo, human allografts formed by the combination of demineralized bone matrix or cartilage particles with SWCNTs were implanted into nude rats, and ectopic bone formation was analyzed. Histological analysis of both types of implants showed high permeability and pore connectivity of the carbon nanotube-soaked implants. Numerous vascularization channels appeared in the formed tissue, additional progenitor cells were recruited, and areas of de novo ossification were found 4 weeks post-implantation. Induction of the expression of bone-related genes and the presence of secreted osteopontin protein were also confirmed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis and immunofluorescence, respectively. In summary, these results are in line with prior contributions that highlight the suitability of SWCNTs as scaffolds with high bone-inducing capabilities both in vitro and in vivo, confirming them as alternatives to current bone-repair therapies.

Keywords: human allografts, demineralized bone matrix, cartilage particles, bone regeneration

Introduction

Current surgical procedures for the treatment of bone defects including those resulting from tumor resection, trauma, and abnormal bone growth enjoy only partial success, and often lead to multiple surgeries. Among these limitations, patients must face responses such as quick degradation of implants, poor osteointegration, and fractures. During the past few decades, efforts have been made to mitigate these challenges through the use of new metal prostheses and the development of new biocompatible materials, such as biodegradable polymers, and collagen- and calcium-based scaffolds.1–4

Nanotechnology offers a wide range of alternatives to design new materials that can be applied to regenerative medicine. Examples of these nanomaterials include carbon nanotubes (CNTs), an allotrope form of carbon5,6 that shows excellent properties to be employed in diverse fields.7–9 In addition, CNT’s geometry resembles triple collagen fibrils.10,11 An individual single-walled CNT (SW-CNT) is a thin fiber about 1–5 μm in length and 0.5–1.5 nm in diameter, closely mimicking the length and diameter of collagen fibrils, making them ideal candidates for tissue engineering. Despite of their beneficial geometry, the application of CNTs in regenerative medicine has caused some controversy; a number of published reports have questioned their biocompatibility.12–15 However, more recent reports on manufactured CNTs using improved methods, which reduces heavy metal componentry, have emphasized their utility and are reviewed by Tran et al.16

The application of any type of biomaterial in bone regeneration must satisfy three criteria; the biomaterial must be: 1) osteoconductive, sustaining colonization by precursor cells and allowing the formation of new vessels; 2) osteoinductive, stimulating bone cell differentiation of precursors; and 3) osteointegrative with host bone tissue. Using these three criteria, we and others have shown that high-purity CNT preparations sprayed on glass surfaces sustained bone cell proliferation as well as electrical activities underlying osteoblast secretory functions and matrix mineralization.17–19 In addition, in closely related bioengineering fields, chemically modified CNTs alone or in combination with distinct composite materials have been applied to facilitate neuronal growth, cartilage, and myocardial tissue differentiation, among other applications.20–32 Furthermore, CNTs in suspension have also been investigated as potential carriers for drug delivery, and have been shown to have no effect on vital functions of cells.31,32

In the current work, we have evaluated the bone-inducing properties of carboxyl (COOH)-modified CNTs by conducting in vitro experiments on two models of progenitor cells, human fetal osteoblasts (hFOBs) and murine embryonic stem cells (mESCs), and we have further investigated bone induction in vivo in a rat model. While multi-walled, negatively charged CNTs altered the adhesive and proliferative properties of cells, single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) in suspension had a putative cytotoxic impact at concentrations >20 μg/mL. However, SWCNTs improved differentiation of both hFOB and mESC progenitors into osteoblasts in vitro, as confirmed by an increase in messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA), abundance of bone-lineage genes, an earlier induction of extracellular matrix (ECM) mineralization, and induced secretion of osteocalcin (Ocn) protein. In vivo, human allografts of demineralized bone matrix (DBM) and cartilage particles soaked in SWCNT suspension were implanted into athymic rats. Histological analysis of resulting tissue and mRNA levels of bone marker genes suggested that the tissue formed upon transplantation of SWCNT-soaked DBM was more mature than that of SWCNT-soaked cartilage particles. In summary, our results highlight the relevance of SWCNT-based scaffolds in promoting bone formation in vivo and in vitro.

Materials and methods

CNT preparation

Aqueous solutions of carboxyl-modified single- and multi-walled CNTs, (COOH–SWCNTs and COOH–MWCNTs, respectively; NanoLab Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) were sprayed onto glass coverslips (30 mm diameter). Briefly, 100 μg/mL of sonicated CNT suspension was sprayed onto preheated (160°C) glass coverslips, allowed to air-dry, and then irradiated with ultraviolet light prior to use in cell culture. CNT features are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Technical characteristics of carbon nanotubes

| Carbon nanotubes | Length | Diameter | Purity | Chemical functionalization | Fabrication method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COOH–SWCNTs | 1–5 μm | 1.5 nm | 95% | COOH– | CVD |

| COOH–MWCNTs | 5–20 μm | 25 nm | 95% | COOH– | CVD |

Abbreviations: CNTs, carbon nanotubes; COOH–SWCNTS, carboxyl-modified single-walled nanotubes; COOH–MWCNTs, carboxyl-modified multi-walled nanotubes, CVD, chemical vapor deposition.

Cell culture

hFOBs (line 1.19) and mESCs (line D3) were obtained from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA). hFOB 1.19 cells were cultured as previously described.33 Culture medium was changed every other day and differentiation induced at 39.5°C when cells reached 80% percentage of confluence. Routine culture methods and differentiation media for mESCs containing β-glycerophosphate, ascorbic acid, and 1α 25(OH)2 vitamin D3 factors were used, as previously described.34 For both hFOB 1.19 and mESCs cell lines, 3,500 cells/cm2 were seeded onto CNT-sprayed coverslips, and differentiation was induced for 28 days.

Analysis of cellular morphology

Cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 hour at room temperature (RT). Coverslips were washed three times in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate and RT-incubated in a solution containing 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1% sodium cacodylate. Coverslips were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, and 100%), and subjected to critical-point drying for 1 hour. Specimens were sputter-coated with gold palladium (SCD 040; Oerlikon Balzers Coating AG, Balzers, Liechtenstein) and imaged in a scanning electron microscope (SEM; Philips XL30, Philips/FEI Corporation, Eindhoven, the Netherlands) at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. All SEM reagents were purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA, USA).

Cytotoxicity assays

Cytotoxic influence of in-suspension SWCNTs was determined by XTT (2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2-H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide) assay (XTT cell proliferation assay kit; ATCC) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 4×103 cells/well were seeded into 96-well tissue plates and incubated for 24 hours with SWCNT suspensions at the following concentrations: 1, 5, 10, 20, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μg/mL. Potential release of sprayed SWCNTs from coverslips into the media was assayed for 34 days. Measurements were performed at 490 nm (λ) in a micro-plate absorbance reader (iMark; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Biochemical and immunostaining assays

Quantitation of mineralized ECM from hFOBs and mESCs was performed at day 14, and again at day 28 upon differentiation induction. Briefly, cells were fixed in 100% ethanol for 15 minutes and subsequently stained for 1 hour in 0.2% alizarin red solution (pH 6.4) at RT. Cells were then washed in an ascending ethanol series to remove unspecific signals. Bound alizarin red was extracted using 20% methanol and 10% acetic acid in water. After 15 minutes, the methanolic mixture was transferred to a 96-well plate and quantified at 450 nm. Resulting values were normalized to the protein content (bicinchoninic acid protein assay; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Ocn protein secreted to ECM was detected by immunofluorescence. Cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol/acetone (7:3) for 15 minutes at −20°C. Subsequently, a blocking step was performed with 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.5% bovine serum albumin in 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 30 minutes at 37°C prior to incubation with an anti-osteocalcin rabbit polyclonal antibody (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After washing in 1× PBS, samples were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488 donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) secondary antibody in the presence of 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Millipore) to counterstain nuclei. Secondary antibody was visualized with a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse Ti; Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA). A similar procedure was followed to immune detect osteopontin (Opn) protein.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA isolation from cells (RNAqueous®-4PCR Kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and from the ribcage of 4-week-old rats (RNeasy® Plus Mini Kit; Qiagen NV, Venlo, the Netherlands) was conducted according to manufacturers’ instructions. Total RNA isolation from cartilage fractions was performed as described by Mallein-Gerin and Gouttenoire.35 In all cases, cyclic deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) was synthesized with an iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad Laboratories). Primers used are listed in Table S1. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed in an ABI 7900HT instrument using Fast SYBR® Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Expression fold values are shown as 2(−ΔΔCt), which are relative to control conditions and normalized to endogenous control gene expression. RT-PCR products corresponding to pluripotent genes were visualized on 2% Tris-Borate-EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) agarose gels.

Rat implant preparation and surgery

Thin human femur cortical bone strips, of 10–12 mm in length and 4–5 mm in width, were microperforated with a 350°μ diameter drill, creating 20 perforations/cm2. Lipid was then extracted with 95% ethanol and diethyl ether. Demineralization and sterilization were conducted as described by Gendler.36 After aeration, bone allografts were freeze-dried for 5 days and then packaged into double plastic pouches. One-half of bone implants were treated with SWCNTs, while the other half was not. CNT treatment consisted of placing the implants into 1 g/L COOH–SWCNT solution for 12 hours at 20°C, followed by several washes with running deionized sterile water for 12 hours at 20°C. Before implantation, allografts were reconstituted in physiologic PBS for 30 minutes. Cartilage preparations were excised from cadaver donors under aseptic conditions, as previously described.37,38 Briefly, cartilaginous sections were washed, frozen in liquid nitrogen vapor, and then transferred to a freeze-drying chamber with the external condenser set at 60°C and the sheaf between 20°C–30°C (VirTis Bench Top Pro Freeze Dryer, SP Scientific, Warminster, PA, USA). Cartilage sections were freeze-dried to a residual moisture content of 3%–6%, and subsequently ground in a turbo grinding mill (PALLMANN Maschinenfabrik GmBH & Co. KG, Zweibrücken, Germany) into particles 200–300 μm in size.

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined by the University of California Guidelines for Animal Research. Isoflurane-vapor-anesthetized, 6-week-old nude rats (Crl:NIH-Foxn1rnu) were used for implant surgery. Implant incision and preparation was conducted as previously described.39 Incisions of 1 cm were made parallel to the most caudal rib, and a 1.5 cm cavity prepared for implant placement by inserting a blunt probe rostrally under the skin to create a chamber overlying the lateral rib cage. For each rat, untreated implants were inserted into the cavity on the right side of the animal, and SWCNT-treated implants inserted on the left. Incisions were carefully closed with skin staples, and the animals returned to their cages for recovery. No systemic effects caused by SWCNTs from treated implants were observed on control implants.

Histological analysis

After 4 weeks, excised allografts were fixed in neutral buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich) and post-fixed in Bouin’s fluid (Sigma-Aldrich) after washing for 24 hours in 1× PBS. Specimens were then dehydrated in graded ethanol, cleared in xylene, embedded flat in paraffin, and sectioned along their longitudinal axis at 10 μm. Sections were collected on acid-cleaned glass slides, dried at 40°C overnight, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. After staining, sections were dehydrated, cover-slipped with DPX Mountant (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA) and digitally imaged with a cooled charge-coupled device camera mounted on an Olympus DMRXA microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Images collected at the same magnification were cropped and assembled into composites with Adobe Photoshop CS4 Software (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of mean of at least three independent experiments. For statistical analysis, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used and a value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of SWCNT scaffolds on cell morphology

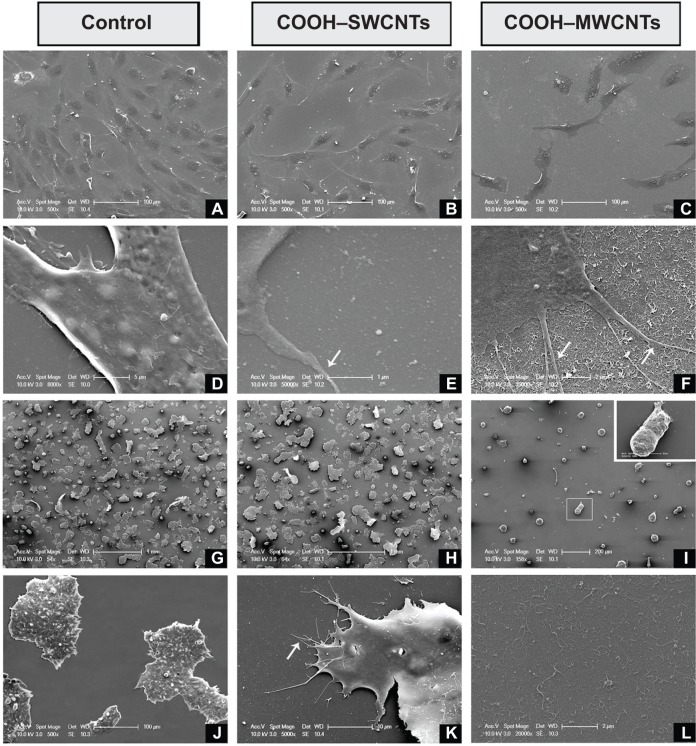

To investigate whether CNT-induced nanoroughness might cause putative changes on cell number and morphology, both hFOB and mESC cell lines were cultured on COOH–SW-CNT-and COOH–MWCNT-sprayed coverslips for 3 days. SEM revealed typical cell diameters of ~40 μm in hFOB cells, with flat, growing cell bodies (Figure 1A–C). Higher magnification revealed the presence of nanometer-scale cytoplasmic prolongations (Figure 1E and F) for these cells on both types of CNT scaffolds, while prolongations were less abundant – or practically absent – on control coverslips (Figure 1D). Nanosized prolongations were more abundant on MWCNTs (Figure 1F), suggesting that cells attempted to adhere to this type of substrate (denoted by white arrows in Figure 1F). While hFOBs showed a reduction in number when grown on MWCNTs (Figure 1C), mESCs showed typical colony morphology on control (Figure 1G and H) and on SWCNT (Figure 1J and K) coverslips. The number of hFOB and mESC colonies was compared, and similar results were noted for controls (Figure 1G) and SWCNTs (Figure 1H). However, similar to other results described in this section, a reduction in mECS colony number plus an abnormally round morphology was observed on COOH–MWCNTs (Figure 1I), confirming our previous suspicions that an increase in the dimension of our tested scaffolds represented an impairment of these cell lines’ adhesion. In addition, higher magnification revealed the presence of nano-prolongations on scaffolds, which allow adhesion of colonies to COOH–SWCNTs (Figure 1K); in contrast, nano-prolongations were absent from controls (Figure 1J). This data confirmed the notion that a dimensional increase in scaffold geometry from single- to multi-walled structures impaired cellular adhesion, and that this impairment is independent of the cell line tested. Therefore, further investigation on COOH–MWCNT substrates was not included in this work.

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy micrographs of hFOB (A–F) and mESC (G–L) cell lines after 3 days of culture on control and carboxyl-modified CNTs.

Notes: hFOB cells growing on control, COOH–SWCNT, and COOH–MWCNT substrates (A, B, and C, respectively); establishment of cytoplasmic nanoprotrusions on control, COOH–SWCNT, and COOH–MWCNT scaffolds, as seen at higher magnification (D, E, and F, respectively); and mESC colonies adhering to control scaffolds, COOH–SWCNTs, and COOH–MWCNTs (G, H, and I, respectively). Inset (I) shows abnormal morphology of colonies grown on COOH–MWCNTs magnified; higher magnifications depict establishment of nanoprotrusions on control and COOH–SWCNT substrates (J and K, respectively); inferred increase in nanoroughness introduced by COOH–MWCNTs (L). White arrows in Figures 1E, F and K depict the establishment of cytoplasmic prolongations of the cells to adhere to the scaffold.

Abbreviations: hFOB, human fetal osteoblast; mESC, murine embryonic stem cell; CNTs, carbon nanotubes; COOH–SWCNTs, carboxyl-modified single-walled CNTs; COOH–MWCNTs, carboxyl-modified multi-walled CNTs.

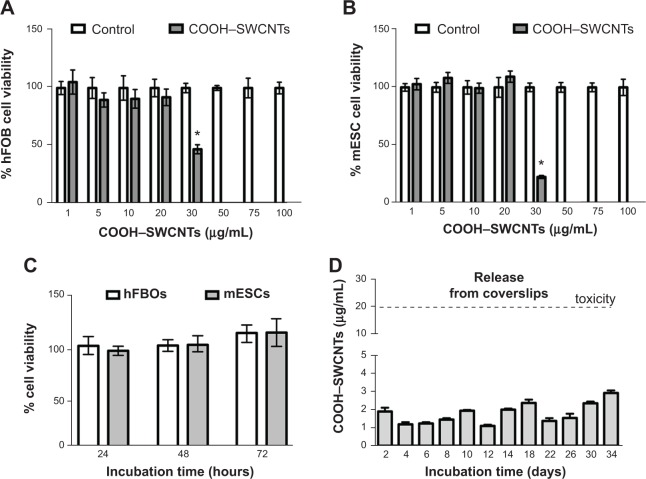

Impact of SWCNTs on cell viability

To determine possible cytotoxic effects of SWCNTs in suspension on the proliferative properties of both progenitors, XTT assays were conducted. SWCNT concentrations ranged from 1–100 μg/mL. Our assays revealed that COOH–SWCNT concentrations >20 μg/mL elicited cytotoxicity (P<0.01) in both cell lines, causing a decrease to 47% and 22% viable cells for hFOB and mESC lines, respectively (Figure 2A and B). Based on these results, we then determined whether the highest noncytotoxic concentration would affect cell proliferation long-term. Cells cultured for up to 72 hours did not show any overt negative effects on their proliferative properties (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Study of cytotoxic effects produced by in-suspension SWCNTs on hFOB and mESC cell lines.

Notes: Percentage of hFOB (A) and mESC (B) cell viability after 24 hours’ exposure to increasing concentrations of in-suspension COOH–SWCNTs (1–100 μg/mL); percentage of hFOB and mESC cell viability (C) at different time points (24, 48, and 72 hours) in the presence of 20 μg/mL COOH–SWCNTs; concentration of COOH–SWCNTs released into medium (D) from coverslips (days 2–34). Dashed line parallel to x-axis delimits COOH–SWCNT concentration threshold for cytotoxic effects. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicate experiments; *P<0.01.

Abbreviations: SWCNTs, single-walled carbon nanotubes; hFOB, human fetal osteoblast; mESC, murine embryonic stem cell; COOH–SWCNTs, carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotubes; SD, standard deviation.

Finally, release of SWCNTs from coverslips into the medium was analyzed for a period of 34 days (Figure 2D) by collecting the liquid phase every 2 days, as described in the “Methods” section. Maximum SWCNT concentration peaks of ~2.5–3 μg/mL were found at 18, 30, and 34 days (Figure 2D). These concentrations were about 10-fold lower than the cytotoxic concentration identified previously in this section (Figure 2A and B). Minimal release of SWCNTs into the medium ensured the absence of cytotoxic effects, predicated further experimentation, and validated the suitability of the chosen coating procedure.

Influence of SWCNT scaffolds on osteogenic differentiation

To examine osteoinductive effects of SWCNTs on mESCs, we initially investigated whether SWCNTs could provoke any change in mRNA abundance of the three master regulators of pluripotency, Oct3/4, Nanog, and Sox-2. By conventional and quantitative RT-PCR (Figure S1), mRNA abundance of these genes was measured from three different passages (P3, P6, and P9) of cells cultured on SWCNTs. Levels of all three mRNAs remained unchanged compared to levels found for cells grown on control coverslips. From these quantitative data and from the absence of morphological changes in mESC colonies, it may be inferred that CNTs used in our current research do not alter the identity of undifferentiated ESCs.

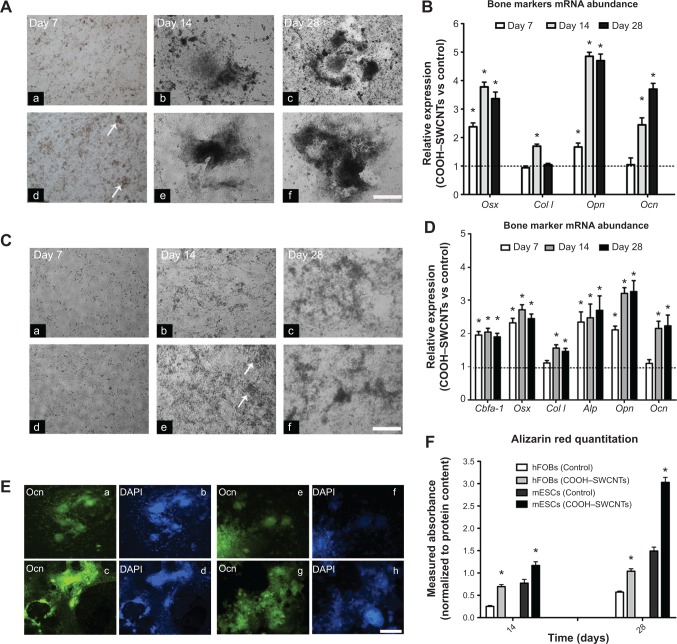

We also investigated the influence of SWCNTs on osteogenic differentiation potential of both mESC and hFOB progenitors (Figure 3A, panels a–f, respectively). For mESCs, a cell medium lacking leukemia inhibitor factor but with proper osteogenic factors added, was used. The earliest mineralization on SWCNT scaffolds was observed at day 7 (Figure 3A, panel d), as evidenced by the presence of small, mineralized aggregates (indicated by white arrows), which were absent on control coverslips (Figure 3A, panel a). Differences in mineralization became more evident at days 14 and 28, as larger mineralized aggregates were found on SWCNT coverslips (Figure 3A, panels e and f) as compared to controls (Figure 3A, panels b and c).

Figure 3.

Induced osteogenic differentiation in mESC and hFOB cell lines cultured on COOH–SWCNTs.

Notes: Representative images taken at days 7, 14, and 28 of mESCs (A) and hFOBs (C) on control (panels a–c), and COOH–SWCNT (panels d–f) substrates. White arrows denote formation of early-mineralized nodules into ECM. Scale bar =500 μm. Quantitative expression of bone-related markers shown in bar graphs (B, D, and F). Results normalized to endogenous B-actin relative to controls. Dashed lines (B and D) indicate values of target genes in control conditions; *P<0.01 vs respective control group. Immune-fluorescence images (E) depict presence of secreted Ocn (green color) in mESCs and hFOBs on control (panels a and e) and COOH–SWCNT (panels c and g) substrates. Scale bar =500 μm. Counterstaining with DAPI (blue color) is shown in (E) (panels b, d, f, and h). Bar graph (F) shows normalized alizarin red quantitation from hFOBs and mESCs on all substrates. *P<0.01.

Abbreviations: mESC, murine embryonic stem cell; hFOB, human fetal osteoblast; COOH–SWCNTs, carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotubes; ECM, extracellular matrix; mRNA, messenger RNA; vs, versus; Ocn, osteocalcin protein; DAPI, 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Cbfa-1, core-binding alpha factor I; Osx, osterix; Col I, collagen type I; Alp, alkaline phosphatase; Opn, osteopontin; Ocn, osteocalcin.

mRNA abundance of representative bone marker genes osterix (Osx), collagen type I (Col I), osteopontin (Opn), and osteocalcin (Ocn) was then assayed. The analysis revealed that expression levels of Osx and Opn genes were significantly upregulated in mESCs differentiated on SWCNTs at all assessed time points (P<0.05, Figure 3B). Specifically, Osx expression was upregulated 2.4-, 3.8-, and 3.4-fold on SWCNTs, followed by similar increases in Ocn expression at the two later time points, reflecting the function of Ocn as a marker of fully matured osteoblasts. In contrast, overall Col I expression did not show any statistical difference compared to controls, except on day 14 when it was slightly increased (to 1.7-fold) from cells differentiated on SWCNTs.

Similarly, mineralized nodules were absent on control coverslips (Figure 3C, panel b), but appeared as early as day 14 in hFOBs cultured on SWCNTs (white arrows in Figure 3C, panel e). Toward the end of the experiment, the number and size of mineralized nodules was only slightly higher and the color only slightly darker on SWCNTs than on control coverslips (Figure 3C, panels c and f, respectively). We quantified the expression levels of bone-related genes using the same methodology (Figure 3D). Due to only minor microscopic differences observed in osteogenic yield, additional osteoblast genes were included in the assessment of bone specific gene expression: core binding factor alpha-1 (Cbfa-1), and alkaline phosphatase (Alp), two early–intermediately expressed markers. The expression level of all genes was significantly elevated at all assessed time points, with the exception of Col I and Ocn, which were elevated from day 14 onward. Specifically, Cbfa-1, Osx, and Alp genes showed an early, steady state expression maintained at a similar level (2- to 2.5-fold over controls) across the 28-day window on SWCNTs. For Opn and Ocn, a steeper upregulation was found between the first and second week of differentiation, and their expression was maintained at all later time points at ~3.7- and 2.7-fold over controls, respectively. Taken together, our results revealed a positive influence of SWCNT scaffolds on osteogenic differentiation yield of hFOB and mESC progenitors.

To further validate whether the presence of SWCNT scaffolds accelerates the formation of fully mature osteoblast cells, we evaluated the presence of secreted Ocn protein at day 28 of the osteogenic induction protocol. As seen in Figure 3E, results revealed a major abundance of Ocn, shown in green, when mESCs and hFOBs were differentiated on SWCNTs (panels c and g, respectively) compared to control differentiations (panels a and e), correlating with mRNA levels discussed previously in this section. Finally, alizarin red assays at days 14 and 28 confirmed a general increase in the deposition of mineralized matrix on SWCNTs. This deposition was more accelerated at the end of differentiation (2-fold) than at mid-term evaluation (1.5-fold, day 14) for mESCs. Similarly, mineralization from differentiated hFOBs revealed an increase of up to 2.75- and 1.8-fold at days 14 and 28 compared to mineralization on control scaffolds.

Ectopic bone formation after DBM and SWCNT-treated cartilage allograft implantation

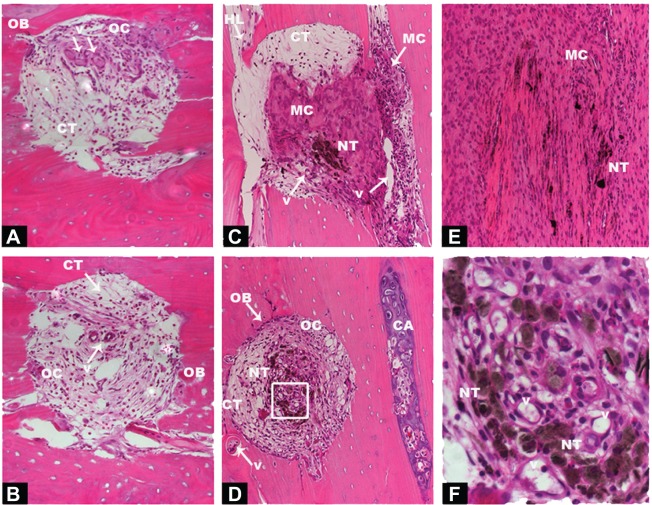

In an attempt to translate in vitro results into in vivo application of CNTs, 6-week-old nude rats were subjected to implantation with human DBM and cartilage particle allografts, which had been soaked in SWCNTs. Implants were subcutaneously placed into pouches in the pectoralis muscle, and subsequent ectopic bone formation observed. To provide an overview of implantation methodology, selected areas and number of perforations made are shown in Figures S2 and S3. Four weeks post-implantation, implant containing both SWCNTs and DBM (indicated as “NT” in Figures 4 and 5) were well populated by host cells and vascular channels, indicating the high permeability and pore interconnectivity of these scaffolds (Figure 4C–E, and at higher magnification in Figure 4F). In both control and treated implants, interiors of microperforations were ingrown with a large number of vascular channels, and with host cells of different morphology ranging from loosely packed connective tissue cells to densely packed, mesenchymal cells, or differentiated active osteoblasts and encased osteocytes (Figure 4A and B and Figure 4C–G for control and SWCNT implants, respectively). The secretory activity of surrounding osteoblasts depositing new bone matrix and thereby eroding the microperforations’ outlines, was also a common phenomenon in both instances, while the recruitment of densely packed mesenchymal cells was greater surrounding SWCNT grafts (Figure 4C and E) than in controls (Figure 4A and B). In addition, cartilaginous areas were highly abundant close to SWCNT/DBM implants, indicating the presence of new endochondral ossification centers (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Histological sections of DBM with or without COOH–SWCNT scaffolds 4 weeks post-implantation on rat pectoris muscle.

Notes: Images from untreated control implants: DBM with COOH–SWCNT scaffolds (A); DBM without COOH–SWCNT scaffolds (B). Images from treated DBM plus COOH–SWCNT-treated implants at 10× magnification (C–E); inset in (D) at 40× magnification (F). Acronyms and white arrows indicate presence of relevant events.

Abbreviations: DBM, demineralized bone matrix; COOH–SWCNT, carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotube; OB, osteoblasts; OC, osteocytes; V, vascular channels; NT, nanotubes; HL, Howship’s lacunae; CA, cartilage; CT, connective tissue; MC, mesenchymal cells.

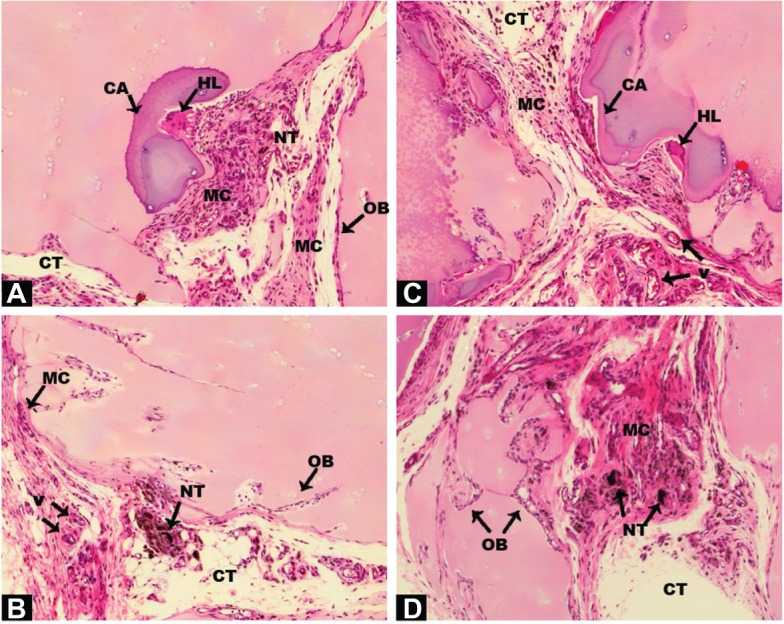

Figure 5.

Histology sections of cartilage granules soaked with COOH–SWCNT scaffolds 4 weeks post-implantation on rat pectoris muscle.

Notes: Sections (A–D) at 10× magnification. All the parts of this Figure are the result of the implantation of human cartilage particles soaked with COOH-SWCNTs. Each part was selected from different areas of the tissue that reveal distinct stages of the osteogenic process. Acronyms and black arrows indicate relevant events.

Abbreviations: COOH–SWCNT, carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotube; OB, osteoblasts; V, vascular channels; NT, nanotubes; HL, Howship’s lacunae; CA, cartilage; CT, connective tissue; MC, mesenchymal cells.

Ectopic bone formation upon implantation of SWCNT-treated cartilage allografts

Human cartilage preparations combined with SWCNTs were also implanted into the pectoralis muscle of nude rats, using the same methodology described in the previous section. Low magnification images show an overview of how and where cartilage-SWCNT implants were placed (Figure S4). Four weeks post-implantation, high compatibility of grafts with host tissue, absence of relevant inflammatory signals, recruitment of mesenchymal progenitor cells, and the presence of aligned osteoblasts were observed (Figure 5A–D). High osteoblast activity was also evidenced by the presence of ossification events on cartilage particles, especially clear in Figure 5A, in all selected areas. However, remarkable differences were found, such as large amounts of connective tissue, Howship’s lacunae which identify multinucleated osteoclasts (Figure 5A and B), and the presence of few osteocytes. This suggested an early–intermediate ossification stage compared to the more advanced ossification in DBM implants.

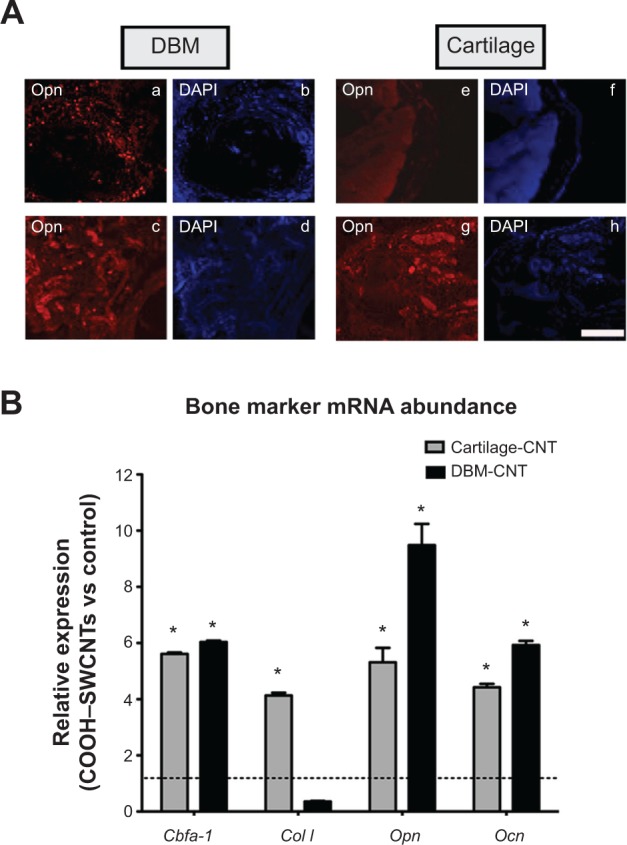

To compare the effectiveness of both transplants quantitatively, mRNA levels of bone-specific genes were used as a measure for osteoinductivity (Figure 6B). Increased expression of Cbfa-1, Col I, Opn, and Ocn genes (5.6-, 4.1-, 5.3-, and 4.4-fold, respectively) was found in cartilage/SWCNT implants compared to untreated groups. Similar behavior was observed in the case of DBM/SWCNT implants, where the expression of Cbfa-1, Opn, and Ocn was 6.0-, 9.5-, and 6.9-fold higher than in the control, while Col I expression was downregulated. These data confirmed the notion that the tissue was more mature in CNT-treated transplants. In addition, the upregulation observed for Opn markers, an early–intermediate indicator of bone formation, correlated with the highest abundance of its encoded protein in both treated specimens (Figure 6A, panels c and g for DBM- and cartilage-treated implants, respectively).

Figure 6.

Immune detection of secreted Opn protein and bone marker expression analysis performed on implants 4 weeks post-implantation.

Notes: The presence of Opn (A) in DBM (panels a–d) and cartilage implants (panels e–h); control DBM and cartilage implants (panels a and e, respectively); Opn in treated DBM and cartilage implants (panels c and g, respectively); counterstaining with DAPI (panels b, d, f, and h); scale bar =500 μm. Ectopic bone formation (B) as measured by mRNA abundance. Results are normalized to endogenous gene Gapdh and are relative to the expression of the tested genes from untreated control implants. Full grey and black bars represent data obtained from Cartilage and DBM treated implants; *represents significant values relative to control type of implants. *P<0.01.

Abbreviations: DBM, demineralized bone matrix; Opn, osteopontin protein; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; cartilage-CNT, cartilage particles soaked in a COOH–SWCNT suspension; DBM-CNT, demineralized bone matrix particles soaked in a COOH–SWCNT suspension; mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid; Cbfa-1, core-binding alpha factor I; Col I, collagen type I; Opn, osteopontin; Ocn, osteocalcin; Gapdh, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; vs, versus; COOH–SWCNT, carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotube.

Discussion

Nanotechnology has allowed the possibility of manufacturing materials, such as CNTs, that can be utilized in distinct biologic fields. Although CNTs have been studied extensively, their applications are still controversial due to the appearance of cytotoxic effects, especially when they are used in suspension.12–15 The main hypothesis for this study was that SWCNTs are ideal scaffolds to promote bone formation due to the similar geometry they share with collagen fibrils, a major component of osteoblasts’ ECM. This capability was assayed with two unspecialized cell lines, and further elucidated in vivo by using a nude rat model. hFOBs were selected as a cellular model for this study, because they proliferate more quickly and are more homogeneous than primary cultured bone cells. In addition, they differentiate upon altering the culture temperature from 33.5°C to 39.5°C, without adding any osteogenic factor.34,40–42 Advantages of employing the second in vitro cell line, murine ESCs, lie in their pluripotent nature,43 hence their capability to differentiate into bone cells,44,45 and in their prior extensive use in the toxicity screening of chemical compounds;44–48 they therefore represent a good model to test CNT-induced toxicity.

To identify whether CNT-based scaffolds induce changes in cellular morphology and cell or colony number of these progenitors, hFOBs and mESCs were subjected to SEM analysis. Three common conclusions were inferred from this analysis: 1) SWCNT modification of the substrate caused nanoscale cytoplasmic protrusions that ensured proper cellular adhesion; 2) SWCNTs did not induce any morphological changes; but 3) MWCNTs induced morphological changes or reduction in cell numbers. The larger dimensions of the MWCNT fibrils thus seemed to impair cell adhesion, and hence proliferation. Although this observation differs from previous reports,28,29 it was in line with our previous research on osteosarcoma rat cells,17 and could explain why SEM analysis – which indirectly revealed distinct levels of adhesion of these progenitors for the selected substrates – failed for similar types of MWCNT scaffolds constructed by other research groups.19 Although we did not further investigate this matter, our observations may be the basis for further exploration into the study of the molecules mediating this difference in cell adhesion.

Second, in trying to shed light on the controversial application of CNTs for future biomedical purposes, we analyzed whether COOH–SWCNTs in suspension might have a cytotoxic effect. Our XTT experiments revealed a toxic effect on cell proliferation when SWCNT concentrations were <20 μg/mL. Clearly, our results are positioned between those that did not describe toxic effects of CNTs in suspension,19 and those that contraindicate their use15 by providing a threshold concentration for toxicity. Furthermore, we evaluated the release of sprayed SWCNTs into the culture medium, a single key to the validation of the coverslip coating procedure, and results revealed the absence of significant leaking during the entire culture time.

Before assaying the impact of SWCNT scaffolds on the osteogenic differentiation of mESCs, we determined the expression profile of canonical stemness genes. Although neither teratoma formation assays nor protein levels of pluripotent markers were investigated, the expression profiles of Oct3/4, Sox-2, and Nanog genes were maintained in mESCs cultured on control and SWCNT coverslips for up to a period of nine cell passages. In a second step, induction of osteogenesis of mESC and hFOB cells was analyzed. The three major phases occurring in osteogenesis have been well established in the past,44 and display a temporally and sequentially organized expression pattern of typical markers. Thus, osteogenic differentiation is controlled by specific transcription factors such as Cbfa-1 and Osx. Osx is a transcription factor acting downstream of Cbfa-1, and is implied in the regulation of genes such as Opn, Ocn, and Col I; it also participates by translating mechanical stimuli into a coordinated cellular response to Cbfa-1.49–51 In general, we observed an upregulation of these markers that was sharper for Osx at early time points, suggesting that the expression of remaining genes might rely on this master regulator. In turn, it is known that ECM mineralization depends on the expression of Opn and Alp genes.52 These two genes were equally upregulated in our experimental conditions. As such, Opn, with encoded product connecting ECM organic and inorganic phases,52 was upregulated at assayed time points. Very surprisingly, we did not find any significant differences in Col I expression during mESC differentiation. This led us to speculate that the presence of CNTs on the coverslips, which mimic collagen fibrils, avoids unnecessary production of collagens. Last, Ocn, a marker of fully differentiated osteoblasts, was upregulated in both cell lines, correlating with the higher abundance of its protein at the end of differentiation.

DBM and cartilage particles are commonly used implants in surgical procedures and dental reconstruction. We analyzed ectopic bone formation in nude rats implanted with human DBM and cartilage allografts soaked with COOH–SWCNTs. The selection of COOH covalently bound to the SWCNT core was based on the fact that COOH increases water solubility of CNTs, thus enhancing their biocompatibility.17 In addition, microperforated bone was used rather than particulate bone preparations to allow for a more precise morphometric measurement of osteogenesis.37 Untreated implants were placed on the right side of each animal, while SWCNT implants were positioned on the left of side, thus reducing putative inter-animal variations. Histological analysis revealed an interconnectivity of implanted biomaterials and the absence of local inflammatory responses, suggesting a high biocompatibility. Erosion of microperforation walls, neo-vessel formation and recruitment of progenitor cells surrounding the biomaterials were an evident phenomenon in all instances 4 weeks after implantation. A large number of immersed osteocytes in SWCNT/DBM perforations suggested a more advanced stage of induced osteogenesis compared to untreated DBM. In contrast, ossification events were delayed in cartilage-based implants, while multinucleated osteoclasts were mainly observed in treated implants, revealing increased bone remodeling activity. Further analysis of gene expression revealed similar trends to prior assays, although the expression of Cbfa-1, Opn, and Ocn expression was more acute compared to control implants, emphasizing the differences between our study models.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrated the osteogenic properties of SWCNTs in three different models: two cellular models from distinct species, and a rodent animal model. Improved osteogenesis was observed using different approaches and was found to be accentuated depending on the precommitment of each cell line. In contrast, results from our in vivo model reinforce prior studies of CNTs described to date.16–19 After 4 weeks’ implantation, initial evidence of enhanced ectopic bone formation was found. Histological sections of human allografts combined with SWCNTs further confirmed by transcriptional analysis of classical bone markers and increased presence of secreted Opn protein, clearly revealed the osteoinductive properties of CNTs. Taken together, these results reinforce prior research done with CNTs and constitute an opened window to continue with further investigations in other models.

Supplementary materials

Analysis of mRNA abundance of pluripotent genes from mESCs cultured on COOH-SWCNTs.

Notes: Left panel, representative agarose gel depicting the PCR products obtained from real-time-PCR analysis of Nanog, Oct 3/4, Sox-2 pluripotency-associated genes and endogenous control gene B-Actin. Total RNA fractions were isolated and cDNA synthesized from cells cultured at passages (P) 3, 6 and 9. Right panel; histogram from real-time PCR analysis measuring the mRNA expression levels from the above pluripotency-associated genes. Results were normalized to endogenous B-Actin and relative to cells grown on glass control substrate. Bar graphs depict the means and standard deviations resulting from the analysis of gene expression from three independent experiments at the passages indicated.

Abbreviations: Oct3/4, Octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4; Nanog, Homeobox protein Nanog; Sox-2, Sex determining region Y-box 2; B-Actin, Beta actin; P3, P6 and P6, cell passages number 3, 6 and 9, respectively; COOH–SWCNT, carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotube; mESC, murine embryonic stem cell; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Composition of haematoxylin-eosin images depicting three perforations of human DBM on rat pectoris muscle.

Notes: Perforations delimited by squared boxes were selected as representative control images in Figure 4 (referred as 4A and 4B). Overlapping of single images (magnification 2.5×) was performed using the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software package.

Abbreviation: DBM, demineralized bone matrix.

Composition of haematoxylin-eosin images depicting fourteen perforations of human DBM soaked in COOH-SWCNTs, on rat pectoris muscle.

Notes: Two out of these fourteen perforations were selected as representative images for DBM/COOH-CNTs implantation in Figure 4 (delimited by squared boxes and referred as 4C and 4D). Out of the perforations region, an area enriched by mesenchymal progenitors was also selected and included in Figure 4 (referred as 4E). Equally done than in Figure S2 overlapping of single images (magnification 2.5×) was performed using the Adobe Photoshop CS4 package.

Abbreviations: COOH–SWCNT, carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotube; DBM, demineralized bone matrix.

Composition of overlapping haematoxylin-eosin images corresponding to the transplantation of human cartilage particles soaked in COOH-SWCNTs on rat pectoris muscle.

Notes: In the composition cartilage particles perforations (referred by CA acronym) and their ossification (densely pink stained areas) can be noticed. Four areas, delimited by black line squared boxes, were selected as representative images of cartilage implants soaked with COOH-SWCNTs in Figure 5 (referred as 5A to 5D). Overlapping of singles images (magnification 2.5×) was performed using the Adobe Photoshop CS4 package.

Abbreviations: COOH–SWCNT, carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotube; COOH-CNT,.

Table S1.

Nucleotide primer sequences of target genes

| Gene | Accession no | Primer sequences (5′–3′) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens | |||

| Osx | NM_152860.1 | F: CCTCTGCGGGACTCAACAAC | 128 |

| R: AGCCCATTAGTGCTTGTAAAGG | |||

| Cbfa1 | NM_001015051 | F: GCGGTGCAAACTTTCTCCAG | 116 |

| R: ACTGCTTGCAGCCTTAAATGAC | |||

| Alp | NM_000478.2 | F: ACTGGTACTCAGACAACGAGAT | 97 |

| R: ACGTCAATGTCCCTGATGTTATG | |||

| Opn | NM_001040058 | F: TCACCTGTGCCATACCAGTTA | 86 |

| R: GGCCACAGCATCTGGGTATT | |||

| Ocn | NM_199173.2 | F: CTCACACTCCTCGCCCTATTG | 109 |

| R: GCTTGGACACAAAGGCTGCAC | |||

| Col I | NM_000088.3 | F: TGTTCAGCTTTGTGGACCTC | 111 |

| R: TTGGTGGGATGTCTTCGTCT | |||

| B-Actin | NM_001101.3 | F: GAGCACAGAGCCTCGCCTTT | 70 |

| R: TCATCATCCATGGTGAGCTGG | |||

| Rattus norvegicus | |||

| Cbfa-1 | NM_053304.1 | F: AGCCACACGTGTAGTAAAGGCTCA | 170 |

| R: ATTCCACTTCCTGCAAAGCTGCTG | |||

| Col I | NM_013414.1 | F: ACTTCCCTACCCAGCACCTTCAAA | 198 |

| R: ATGTTTCCAGTCTGCTGTGACCCT | |||

| Ocn | NM_053470 | F: AGAACAGACAAGTCCCACACAGCA | 185 |

| R: TATTCACCACCTTACTGCCCTCCT | |||

| Opn | NM_012881.2 | F: TGAGTTTGGCAGCTCAGAGGAGAA | 199 |

| R: ATCATCGTCCATGTGGTCATGGCT | |||

| Gapdh | NM_130458.3 | F: ACAAGATGGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGA | 199 |

| R: AGCTTCCCATTCTCAGCCTTGACT | |||

| Mus musculus | |||

| Osx | NM_017008.4 | F: TCCCTGGATATGACTCATCCCT | 93 |

| R: CCAAGGAGTAGGTGTGTTGCC | |||

| Col I | NM_007743.2 | F: AGTCGATGGCTGCTCCAAAA | 118 |

| R: AGCACCACCAATGTCCAGAG | |||

| Opn | NM_001204201.1 | F: GGCTGAATTCTGAGGGACTAACTA | 125 |

| R: AAGCTTCTTCTCCTCTGAGCTG | |||

| Ocn | NM_031368 | F: CGCTACCTTGGAGCTTCAGT | 88 |

| R: ATAGCTCGTCACAAGCAGGG | |||

| Oct3/4 | NM_001252452 | F: AGAGGATCACCTTGGGGTACA | 96 |

| R: CGAAGCGACAGATGGTGGTC | |||

| Nanog | NM_028016 | F: CACAGTTTGCCTAGTTCTGAGG | 87 |

| R: GCAAGAATAGTTCTCGGGATGAA | |||

| Sox-2 | NM_011443 | F: CGGCACAGATGCAACCGAT | 85 |

| R: CCGTTCATGTAGGTCTGCG | |||

| B-Actin | NM_007393.3 | F: GCTCCGGCATGTGCAAAG | 96 |

| R: CCATCACACCCTGGTGCCTA | |||

Abbreviations: Alp, Alkaline phosphatase; Cbfa-1, Core-binding factor alpha1; Col I, Collagen type I; Ocn, Osteocalcin; Opn, Osteopontin; Osx, Osteorix; Nanog, Nanog homeobox; Oct3/4, Octamer-binding transcription factor 4; Sox-2, SRY-box containing gene 2; B-Actin, Beta-actin; Gapdh, Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Public Health grant DK-07115-01 to LPZ, by the nonprofit Alfonso Martín Escudero Foundation that awarded ABD with a post-doctoral fellowship, and by a grant from the Consejería de Economía, Innovación Ciencia y Empleo granted by the Andalussian Region (Spain) (P10-CTS5865) to JCR-M.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Webster TJ, Ejiofor JU. Increased osteoblast adhesion on nanophase metals: Ti, Ti6Al4V, and CoCrMo. Biomaterials. 2004;25(19):4731–4739. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDonald RA, Laurenzi BF, Viswanathan G, Ajayan PM, Stegemann JP. Collagen-carbon nanotube composite materials as scaffolds in tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;74(3):489–496. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma PX, Zhang RY, Xiao GZ, Franceschi R. Engineering new bone tissue in vitro on highly porous poly(alpha-hydroxyl acids)/hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;54(2):284–293. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200102)54:2<284::aid-jbm16>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shea LD, Wang D, Franceschi RT, Mooney DJ. Engineered bone development from a pre-osteoblast cell line on three-dimensional scaffolds. Tissue Eng. 2000;6(6):605–617. doi: 10.1089/10763270050199550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iijima S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature. 1991;354(6348):56–58. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai H. Carbon nanotubes: synthesis, integration, and properties. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35(12):1035–1044. doi: 10.1021/ar0101640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajayan PM. Nanotubes from carbon. Chem Rev. 1999;99(7):1787–1800. doi: 10.1021/cr970102g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinnott SB. Chemical functionalization of carbon nanotubes. JNN. 2002;2(2):113–123. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2002.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dyke CA, Tour JM. Unbundled and highly functionalized carbon nanotubes from aqueous reactions. Nano Lett. 2003;3(9):1215–1218. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park JB, Lakes RS. Biomaterials: An Introduction. New York: Plenum; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao B, Hu H, Mandal SK, Haddon RC. A bone mimic based on the self-assembly of hydroxyapatite on chemically functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes. Chem Mater. 2005;17(12):3235–3241. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shvedova AA, Castranova V, Kisin ER, et al. Exposure to carbon nanotube material: assessment of nanotube cytotoxicity using human keratinocyte cells. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2003;66(20):1909–1926. doi: 10.1080/713853956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKenzie JL, Waid MC, Shi RY, Webster TJ. Decreased functions of astrocytes on carbon nanofiber materials. Biomaterials. 2004;25(7–8):1309–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui D, Tian F, Ozkan CS, Wang M, Gao H. Effect of single wall carbon nanotubes on human HEK293 cells. Toxicol Lett. 2005;155(1):73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D, Yi C, Zhang D, Zhang J, Yang M. Inhibition of proliferation and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by carboxylated carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano. 2010;4(4):2185–2195. doi: 10.1021/nn901479w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran PA, Zhang LJ, Webster TJ. Carbon nanofibers and carbon nanotubes in regenerative medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61(12):1097–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanello LP, Zhao B, Hu H, Haddon RC. Bone cell proliferation on carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2006;6(3):562–567. doi: 10.1021/nl051861e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanello LP. Electrical properties of osteoblasts cultured on carbon nanotubes. Micro and Nano Lett. 2006;1(1):19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nayak TR, Jian L, Phua LC, Ho HK, Ren Y, Pastorin G. Thin films of functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes as suitable scaffold materials for stem cells proliferation and bone formation. ACS Nano. 2010;4(12):7717–7725. doi: 10.1021/nn102738c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattson MP, Haddon RC, Rao AM. Molecular functionalization of carbon nanotubes and use as substrates for neuronal growth. J Mol Neurosci. 2000;14(3):175–182. doi: 10.1385/JMN:14:3:175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu H, Ni YC, Montana V, Haddon RC, Parpura V. Chemically functionalized carbon nanotubes as substrates for neuronal growth. Nano Lett. 2004;4(3):507–511. doi: 10.1021/nl035193d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu H, Ni YC, Mandal SK, et al. Polyethyleneimine functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes as a substrate for neuronal growth. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109(10):4285–4289. doi: 10.1021/jp0441137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stout DA, Basu B, Webster TJ. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid): carbon nanofiber composites for myocardial tissue engineering applications. Acta Biomater. 2011;7(8):3101–3112. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roman JA, Niedzielko TL, Haddon R, Parpura V, Floyd CL. Single-walled carbon nanotubes chemically functionalized with polyethylene glycol promote tissue repair in a rat model of spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28(11):2349–2362. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sá MA, Andrade VB, Mendes RM, et al. Carbon nanotubes functionalized with sodium hyaluronate restore bone repair in diabetic rat sockets. Oral Dis. 2013;19(5):484–493. doi: 10.1111/odi.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendes RM, Silva GA, Caliari MV, Silva EE, Ladeira LO, Ferreira AJ. Effects of single wall carbon nanotubes and its functionalization with sodium hyaluronate on bone repair. Life Sci. 2010;87(7–8):215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tonelli FM, Santos AK, Gomes KN, et al. Carbon nanotube interaction with extracellular matrix proteins producing scaffolds for tissue engineering. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:4511–4529. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S33612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holmes B, Castro NJ, Li J, Keidar M, Zhang LG. Enhanced human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell functions in novel 3D cartilage scaffolds with hydrogen treated multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Nanotechnology. 2013;24(36):365102. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/24/36/365102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen YS, Hsiue GH. Directing neural differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by carboxylated multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Biomaterials. 2013;34(21):4936–4944. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimizu M, Kobayashi Y, Mizoguchi T, et al. Carbon nanotubes induce bone calcification by bidirectional interaction with osteoblasts. Adv Mater. 2012;24(16):2176–2185. doi: 10.1002/adma.201103832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cherukuri PM, Bachilo SM, Litovsky SH, Weisman RB. Near-infrared fluorescence microscopy of single-walled carbon nanotubes in phagocytic cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(48):15638–15639. doi: 10.1021/ja0466311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi Kam NW, Jessop TC, Wender PA, Dai H. Nanotube molecular transporters: internalization of carbon nanotube-protein conjugates into mammalian cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(22):6850–6851. doi: 10.1021/ja0486059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris SA, Enger RJ, Riggs BL, Spelsberg TC. Development and characterization of a conditionally immortalized human fetal osteoblastic cell line. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10(2):178–186. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuske B, Savkovic V, zur Nieden NI. Improved media compositions for the differentiation of embryonic stem cells into osteoblasts and chondrocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;690:195–215. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-962-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mallein-Gerin F, Gouttenoire J. RNA extraction from cartilage. In: Sabatini M, Pastoureau P, De Ceuninck F, editors. Cartilage and Osteoarthritis. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2004. pp. 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gendler E. Perforated demineralized bone matrix: a new form of osteoinductive biomaterial. J Biomed Mater Res. 1986;20(6):687–697. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820200603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malinin TI, inventor, University of Miami, assignee Cartilage composition and process for producing the cartilage composition. 2012. Nov 27, United States patent US8318212.

- 38.Malinin TI, Carpenter EM, Temple HT. Implantation of non-human primate particulate cartilage into athymic rats; Program and abstracts of the Tissue Engineering International and Regenerative Medicine Society annual conference; December 11–14, 2011; Houston, Texas (USA). Abstract 0165. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carpenter EM, Gendler E, Malinin TI, Temple HT. Effect of hydrogen peroxide on osteoinduction by demineralized bone. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2006;35(12):562–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balani K, Anderson R, Laha T, et al. Plasma-sprayed carbon nanotube reinforced hydroxyapatite coatings and their interaction with human osteoblasts in vitro. Biomaterials. 2007;28(4):618–624. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Lim JY, Donahue HJ, Dhurjati R, Mastro AM, Vogler EA. Influence of substratum surface chemistry/energy and topography on the human fetal osteoblastic cell line hFOB 1.19: phenotypic and genotypic responses observed in vitro. Biomaterials. 2007;28(31):4535–4550. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brama M, Rhodes N, Hunt J, et al. Effect of titanium carbide coating on the osseointegration response in vitro and in vivo. Biomaterials. 2007;28(4):595–608. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292(5819):154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.zur Nieden NI, Kempka G, Ahr HJ. In vitro differentiation of embryonic stem cells into mineralized osteoblasts. Differentiation. 2003;71(1):18–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2003.700602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buttery LD, Bourne S, Xynos JD, et al. Differentiation of osteoblasts and in vitro bone formation from murine embryonic stem cells. Tissue Eng. 2001;7(1):89–99. doi: 10.1089/107632700300003323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.zur Nieden NI, Kempka G, Ahr HJ. Molecular multiple endpoint embryonic stem cell test – a possible approach to test for the teratogenic potential of compounds. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;194(3):257–269. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.zur Nieden NI, Baumgartner L. Assessing developmental osteotoxicity of chlorides in the embryonic stem cell test. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;30(2):277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuske B, Pulyanina PY, zur Nieden NI. Embryonic stem cell test: stem cell use in predicting developmental cardiotoxicity and osteotoxicity. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;889:147–179. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-867-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ducy P, Zhang R, Geoffroy V, Ridall AL, Karsenty G. Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell. 1997;89(5):747–754. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harada H, Tagashira S, Fujiwara M, et al. Cbfa1 isoforms exert functional differences in osteoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(11):6972–6978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.6972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao Y, Wang C, Li S, et al. Expression of osteorix in mechanical stress-induced osteogenic differentiation of periodontal ligament cells in vitro. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116(3):199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKee MD, Nanci A. Osteopontin: an interfacial extracellular matrix protein in mineralized tissues. Connect Tissue Res. 1996;35(1–4):197–205. doi: 10.3109/03008209609029192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Analysis of mRNA abundance of pluripotent genes from mESCs cultured on COOH-SWCNTs.

Notes: Left panel, representative agarose gel depicting the PCR products obtained from real-time-PCR analysis of Nanog, Oct 3/4, Sox-2 pluripotency-associated genes and endogenous control gene B-Actin. Total RNA fractions were isolated and cDNA synthesized from cells cultured at passages (P) 3, 6 and 9. Right panel; histogram from real-time PCR analysis measuring the mRNA expression levels from the above pluripotency-associated genes. Results were normalized to endogenous B-Actin and relative to cells grown on glass control substrate. Bar graphs depict the means and standard deviations resulting from the analysis of gene expression from three independent experiments at the passages indicated.

Abbreviations: Oct3/4, Octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4; Nanog, Homeobox protein Nanog; Sox-2, Sex determining region Y-box 2; B-Actin, Beta actin; P3, P6 and P6, cell passages number 3, 6 and 9, respectively; COOH–SWCNT, carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotube; mESC, murine embryonic stem cell; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Composition of haematoxylin-eosin images depicting three perforations of human DBM on rat pectoris muscle.

Notes: Perforations delimited by squared boxes were selected as representative control images in Figure 4 (referred as 4A and 4B). Overlapping of single images (magnification 2.5×) was performed using the Adobe Photoshop CS4 software package.

Abbreviation: DBM, demineralized bone matrix.

Composition of haematoxylin-eosin images depicting fourteen perforations of human DBM soaked in COOH-SWCNTs, on rat pectoris muscle.

Notes: Two out of these fourteen perforations were selected as representative images for DBM/COOH-CNTs implantation in Figure 4 (delimited by squared boxes and referred as 4C and 4D). Out of the perforations region, an area enriched by mesenchymal progenitors was also selected and included in Figure 4 (referred as 4E). Equally done than in Figure S2 overlapping of single images (magnification 2.5×) was performed using the Adobe Photoshop CS4 package.

Abbreviations: COOH–SWCNT, carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotube; DBM, demineralized bone matrix.

Composition of overlapping haematoxylin-eosin images corresponding to the transplantation of human cartilage particles soaked in COOH-SWCNTs on rat pectoris muscle.

Notes: In the composition cartilage particles perforations (referred by CA acronym) and their ossification (densely pink stained areas) can be noticed. Four areas, delimited by black line squared boxes, were selected as representative images of cartilage implants soaked with COOH-SWCNTs in Figure 5 (referred as 5A to 5D). Overlapping of singles images (magnification 2.5×) was performed using the Adobe Photoshop CS4 package.

Abbreviations: COOH–SWCNT, carboxyl-modified single-walled carbon nanotube; COOH-CNT,.

Table S1.

Nucleotide primer sequences of target genes

| Gene | Accession no | Primer sequences (5′–3′) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homo sapiens | |||

| Osx | NM_152860.1 | F: CCTCTGCGGGACTCAACAAC | 128 |

| R: AGCCCATTAGTGCTTGTAAAGG | |||

| Cbfa1 | NM_001015051 | F: GCGGTGCAAACTTTCTCCAG | 116 |

| R: ACTGCTTGCAGCCTTAAATGAC | |||

| Alp | NM_000478.2 | F: ACTGGTACTCAGACAACGAGAT | 97 |

| R: ACGTCAATGTCCCTGATGTTATG | |||

| Opn | NM_001040058 | F: TCACCTGTGCCATACCAGTTA | 86 |

| R: GGCCACAGCATCTGGGTATT | |||

| Ocn | NM_199173.2 | F: CTCACACTCCTCGCCCTATTG | 109 |

| R: GCTTGGACACAAAGGCTGCAC | |||

| Col I | NM_000088.3 | F: TGTTCAGCTTTGTGGACCTC | 111 |

| R: TTGGTGGGATGTCTTCGTCT | |||

| B-Actin | NM_001101.3 | F: GAGCACAGAGCCTCGCCTTT | 70 |

| R: TCATCATCCATGGTGAGCTGG | |||

| Rattus norvegicus | |||

| Cbfa-1 | NM_053304.1 | F: AGCCACACGTGTAGTAAAGGCTCA | 170 |

| R: ATTCCACTTCCTGCAAAGCTGCTG | |||

| Col I | NM_013414.1 | F: ACTTCCCTACCCAGCACCTTCAAA | 198 |

| R: ATGTTTCCAGTCTGCTGTGACCCT | |||

| Ocn | NM_053470 | F: AGAACAGACAAGTCCCACACAGCA | 185 |

| R: TATTCACCACCTTACTGCCCTCCT | |||

| Opn | NM_012881.2 | F: TGAGTTTGGCAGCTCAGAGGAGAA | 199 |

| R: ATCATCGTCCATGTGGTCATGGCT | |||

| Gapdh | NM_130458.3 | F: ACAAGATGGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGA | 199 |

| R: AGCTTCCCATTCTCAGCCTTGACT | |||

| Mus musculus | |||

| Osx | NM_017008.4 | F: TCCCTGGATATGACTCATCCCT | 93 |

| R: CCAAGGAGTAGGTGTGTTGCC | |||

| Col I | NM_007743.2 | F: AGTCGATGGCTGCTCCAAAA | 118 |

| R: AGCACCACCAATGTCCAGAG | |||

| Opn | NM_001204201.1 | F: GGCTGAATTCTGAGGGACTAACTA | 125 |

| R: AAGCTTCTTCTCCTCTGAGCTG | |||

| Ocn | NM_031368 | F: CGCTACCTTGGAGCTTCAGT | 88 |

| R: ATAGCTCGTCACAAGCAGGG | |||

| Oct3/4 | NM_001252452 | F: AGAGGATCACCTTGGGGTACA | 96 |

| R: CGAAGCGACAGATGGTGGTC | |||

| Nanog | NM_028016 | F: CACAGTTTGCCTAGTTCTGAGG | 87 |

| R: GCAAGAATAGTTCTCGGGATGAA | |||

| Sox-2 | NM_011443 | F: CGGCACAGATGCAACCGAT | 85 |

| R: CCGTTCATGTAGGTCTGCG | |||

| B-Actin | NM_007393.3 | F: GCTCCGGCATGTGCAAAG | 96 |

| R: CCATCACACCCTGGTGCCTA | |||

Abbreviations: Alp, Alkaline phosphatase; Cbfa-1, Core-binding factor alpha1; Col I, Collagen type I; Ocn, Osteocalcin; Opn, Osteopontin; Osx, Osteorix; Nanog, Nanog homeobox; Oct3/4, Octamer-binding transcription factor 4; Sox-2, SRY-box containing gene 2; B-Actin, Beta-actin; Gapdh, Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.