Abstract

Chimpanzees exhibit cultural variation, yet examples of successful cultural transmission between wild communities are lacking. Here we provide the first account of tool-assisted predation (“ant fishing”) on Camponotus ants by the Kasekela and Mitumba communities of Gombe National Park. We then consider three hypotheses for the appearance and spread of this behavior in Kasekela: (1) changes in prey availability or other environmental factors, (2) innovation, and (3) introduction. Ant fishing was recognized as habitual in the Mitumba community by 1992, soon after their habituation began. Apart from one session in 1978, Camponotus predation (typically with tools) was documented in the Kasekela community beginning only in 1994, despite decades of prior observation. By February 2010, ant fishing was customary in Kasekela and with one exception was practiced exclusively by chimpanzees born after 1981 and immigrant females. We hypothesize that changes in insect prey availability over time and/or the characteristics of one popular ant-fishing site may have influenced the establishment of ant fishing. Though innovation cannot be completely ruled out, the circumstantial evidence suggests that a Mitumba immigrant introduced ant fishing to Kasekela. We submit that this report represents the first documented case of successful transmission of a novel cultural behavior between wild chimpanzee communities.

A nonanthropocentric definition of culture describes the concept as “group-specific behavior that is acquired, at least in part, from social influences” (McGrew 1998:305). By this definition, there is evidence for cultural variation in chimpanzees (McGrew 1992, 2004; Whiten et al. 1999, 2001), as well as other primates (Kawai 1965; Perry et al. 2003; van Schaik et al. 2003), cetaceans (Rendell and Whitehead 2001), birds (West, King, and White 2003), and even fish (Brown and Laland 2003). Despite broad recognition that socially learned patterns of behavior exist in many organisms, vigorous debate continues among anthropologists, biologists, and psychologists over applying the concept of “culture” to nonhuman species (Byrne et al. 2004).

Whiten et al. (1999, 2001) reviewed 65 behaviors observed across nine chimpanzee communities in order to identify patterns of cultural variation. Of these, 39 were categorized as customary (“pattern occurs in all or most able-bodied members of at least one age-sex class [e.g., adult males]”) or habitual (“pattern is not customary but has been seen repeatedly in several individuals, consistent with some degree of social transmission”) in at least one community but absent in at least one other and where an ecological explanation for the difference was not evident (Whiten et al. 2001:1488). The authors deemed the geographic distribution of several cultural behaviors as consistent with single origins, while those of many others were deemed consistent with multiple origins or inconclusive.

The appearance and spread of novel behaviors within chimpanzee communities is known from both wild and captive settings. Boesch (1995) provided examples of innovation—leaf clipping, leaf cutting, and day nest building—that appeared and disseminated through a community of the Taï Forest in Côte d'Ivoire, as well as other behaviors—for example, eating grubs, larvae, and mushrooms with tools—that appeared but did not disseminate. At the Yerkes Regional Primate Center, hand-clasp grooming was invented by an adult female and spread to other members of her social group, who continued the practice after her removal (Bonnie and de Waal 2006; de Waal and Seres 1997). Nishida, Matsusaka, and McGrew (2009) documented many novel behaviors that appeared within communities of the Mahale Mountains in Tanzania, though none spread between communities. Ohashi and Matsuzawa (2011) reported that members of the Bossou community in Guinea learned how to disable snares. Whiten, Horner, and de Waal (2005; Whiten et al. 2007) demonstrated that captive chimpanzees can readily acquire novel tool behaviors from humans or conspecifics and that such behaviors can propagate both within social groups and between groups in visual contact.

Wild chimpanzees exhibit male philopatry and female transfer, though juveniles of either sex sometimes transfer with their mothers (Goodall 1986). Given the extremely aggressive nature of most encounters involving extragroup males (Goodall 1986), any cultural transmission between wild chimpanzee communities most likely occurs through female transfer. However, possible examples of this process are rare. McGrew et al. (2001) described two variations (palm-to-palm and non-palm-to-palm) of hand-clasp grooming (McGrew and Tutin 1978) in neighboring Mahale communities. They concluded that the palm-to-palm hand clasp was a custom of K-group but not of M-group. Nakamura and Uehara (2004) later clarified that the palm-to-palm variant did occur in M-group but only in dyads involving a female immigrant (Gwekulo [GW]) from K-group. Because this hand-clasp pattern was never seen in dyads without GW, its presence in M-group represents a failed transfer of a cultural variant. When or how the broader cultural pattern of hand-clasp grooming originally appeared and spread among Mahale communities is not known. Biro et al. (2003; Biro 2011) introduced locally unavailable (and so presumably unfamiliar) Coula edulis nuts at the outdoor laboratory used in studies of the nut-cracking Bossou community. One immigrant female (Yo) cracked the nuts with no hesitation, suggesting that she emigrated from a natal group with access to Coula. Yo's nut cracking appeared to serve as a catalyst for juveniles (but not other adults) to crack the unfamiliar nuts. Eighteen years after the experiments began, Coula nut cracking was established as customary at Bossou (Biro 2011). However, continued access to Coula nuts occurs only through human intervention. Apart from these experiments we know of no reported case of successful cultural transmission between wild chimpanzee communities.

Insectivory—most often targeting social insects such as ants, termites, and honeybees—is widespread but not universal in wild chimpanzee populations (McGrew 1992), and many associated tool technologies appear to reflect local cultural practices (Whiten et al. 1999, 2001). Though local environmental conditions (e.g., the availability and behavior of particular prey species) can potentially influence insect predation by chimpanzees (Humle 2006; Schöning et al. 2008), communities living in similar habitat with access to the same or similar prey often engage in different insectivory patterns. For example, the Kasekela chimpanzees of Gombe National Park in Tanzania prey on termites (Macrotermes subhyalinus) and termite alates (M. subhyalinus and Pseudacanthotermes spp.), raid the nests of honeybees (Apis mellifera) and stingless Meliponini (e.g., Trigona spp. and Hypotrigona spp.) for honey and brood, and consume leaf galls and caterpillars (Goodall 1986). Kasekela chimpanzees also prey on weaver ants (Oecophylla longinoda), driver ants (Dorylus spp.), and (rarely) Crematogaster ants. Goodall (1986) reported that occasional consumption of other insects, possibly including Camponotus, was observed in Kasekela during decades of research.

Chimpanzees of the M- and (now extinct) K-group of the Mahale Mountains, less than 150 km south of Gombe, live in habitat that is similar in topography, temperature, and seasonality (Collins and McGrew 1988). Mahale chimpanzees differ from their Gombe counterparts in that they ignore Dorylus (Schöning et al. 2008) yet regularly consume both Camponotus and Crematogaster (Nishida 1973; Nishida and Hiraiwa 1982; Nishie 2011; Uehara 1986), as well as several other ant taxa not known to be eaten by chimpanzees else-where (Kiyono 2008; Nishida and Uehara 1983). Mahale chimpanzees typically use tools to prey on at least four species of Camponotus (Camponotus brutus, Camponotus chrysurus, Camponotus maculatus, and Camponotus vividus). Nishida et al. described the behavior as follows:

Fish for carpenter ants … Insert a fishing probe such as peeled bark, unmodified vine, branch, modified branch, midrib of leaf, or scraped wood into the entrance of wood-boring carpenter ants (Camponotus spp.) and withdraw the probe laden with the soldier ants and lick them off with lips and tongue. (Nishida et al. 1999:154)

Camponotus predation by chimpanzees is known from other sites. Yamamoto et al. (2008) observed two ant-fishing sessions for C. brutus by a young male in Bossou. Predation was inferred through fecal analysis at Kasakati in Tanzania (Suzuki 1966) and at Assirik in Senegal through the presence of fresh tools and disturbed ants (McGrew 1992). Camponotus predation was directly observed among chimpanzees of Lopé in Gabon (Tutin and Fernandez 1992) and Gaskaka in Nigeria (Fowler and Sommer 2007). Despite their broad distribution across Africa, Camponotus appear to be consumed at fewer long-term chimpanzee study sites than honeybees, Macrotermes, or Dorylus (McGrew 1992).

For the first 3 decades of research at Gombe, the only reports of Camponotus predation were two possible observations in 1978 (Goodall 1986; but see below). Nishida and Hiraiwa (1982) stated that “Camponotus ants are never and Crematogaster ants are only rarely eaten by chimpanzees of the Gombe National Park” (98). In his comprehensive review of chimpanzee insectivory, McGrew (1992) listed Gombe as a site where Camponotus were present but not eaten, as the “other ants” occasionally consumed as reported by Goodall (1986) could not be conclusively identified and further details were unavailable (W. C. McGrew, personal communication). Whiten et al. (1999, 2001) reported that ant fishing was present at Gombe, based on then-anecdotal reports, but no further details were provided then or since.

In 1994 a young Kasekela female was seen to fish for Camponotus ants. In later years an increasing number of community members were observed to ant fish, even after the first known practitioner had emigrated. By 2010, ant fishing was customary for the community (as defined by Whiten et al. 1999, 2001). Here we provide the first description of predation on Camponotus by Kasekela chimpanzees (almost always via ant fishing) and evaluate three hypotheses regarding the appearance and spread of this behavior within the community.

Hypothesis 1. Predation on Camponotus was already practiced within the Kasekela community but became more frequent due to changes in insect prey availability or other environmental factors.

Hypothesis 2. Predation on Camponotus was an innovation by a native Kasekela chimpanzee.

Hypothesis 3. Predation on Camponotus was introduced to the Kasekela community by an immigrant female.

Methods

This research was conducted in Gombe National Park, Tanzania, where the Kasekela community (n = 61 in February 2010) has been studied since 1960 (Goodall 1986). The northern Mitumba community (n = 26 in February 2010) was habituated by Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) researchers beginning in the late 1980s. The southern Kalande community has been monitored since 1999 but is not habituated (Pusey, Wilson, and Collins 2008).

R. C. O'Malley conducted preliminary observations on the Kasekela community between February 2008 and April 2008 and all-day focal animal follows (Altmann 1974) on 13 adults (>15 years old) between August 2008 and January 2009 and between September 2009 and December 2009. Additional ad lib. observations were made in January–February 2010. He recorded any successful or attempted Camponotus predation by the focal subject or other party members. Whenever possible, sessions were recorded using a Sony DCR-HC52 camcorder. Using definitions modified from those of Nishida and Hiraiwa (1982), we defined a “session” as a period during which a subgroup of chimpanzees is engaged in Camponotus predation as a phase of their rhythm of daily activity and a “bout” as a period during which an individual is engaged in Camponotus predation during a session. R. C. O'Malley noted participants and observers, the start and end of bouts, the host tree species (if known), and other pertinent characteristics (e.g., number of visible entrance holes, prey activity on the tree). After each session, R. C. O'Malley recorded a GPS point (using a Garmin GPSmap 60CSx) and collected discarded tools and prey samples if possible.

The 2008–2010 observations were supplemented by notes and video records provided by W. Wallauer, a researcher for JGI from 1992 to 2007, and E. Wroblewski, a researcher at Gombe from 2006 to 2007. R. C. O'Malley and C. M. Murray also reviewed the digitized long-term “B-record” data set for the Kasekela community (1974–2007), all narrative notes from the B-record that had been translated into English (1995–2007), and the B-record data on the Mitumba community (late 2001–2007) for records of Camponotus predation. They also reviewed the 1978 observations of possible Camponotus predation noted by Goodall (1986; see this reference for full details of the B-record methodology). Finally, in 2008 and 2009, R. C. O'Malley and C. M. Murray conducted interviews with field assistants familiar with both communities to record their recollections of Camponotus predation.

Results

Long-Term Notes and Video Records

As reported by Goodall in a review of Kasekela insectivory:

Occasionally chimpanzees feed on other ant species. In 1978, for example, this was seen five times. Three times these ants were described as small and reddish black, and they may well have been Crematogaster. Twice the ants were black with very large heads and described as big and fierce; probably these were a species of Camponotus, or carpenter ants. (Goodall 1986:254)

In four of the five cases described above, a reread of the original field notes by R. C. O'Malley and C. M. Murray suggested that they actually describe consumption of weaver ants (Oecophylla longinoda) rather than Crematogaster or Camponotus, as the ants are described as living in bound leaf nests or having nests that were physically handled. In the fifth case, Wilkie (WL), his mother, Winkle (WK), and another adult female, Patti (PI), ate “large, fierce” ants from a tree hole. Both Wilkie and Winkle employed tools, consistent with ant fishing as described by Nishida et al. (1999). Both females were immigrants to Kasekela, though their natal communities are not known. The description of these ants suggests they were Camponotus brutus, which were collected throughout the northern and central portions of Gombe in a 2009–2010 social insect survey (O'Malley 2011).

In March of 1994, W. Wallauer observed Flossi (FS; 9-year-old female) ascend a tree and proficiently fish for Camponotus from a small hole for several minutes while her siblings played nearby. He recorded a total of nine complete or partial video recordings of Camponotus predation or attempted predation by Kasekela chimpanzees between 1994 and 2007 (table 1). Because these observations were ad lib., it is likely that additional sessions and practitioners went unrecorded. Camponotus predation continued after Flossi emigrated to Mitumba in 1996 and was practiced by her contemporaries and by chimpanzees born after her departure. Seven of the nine sessions recorded by W. Wallauer were successful, and eight involved tools (in one case a tool was made but not used, presumably due to the ease of acquiring ants by hand in that session). These observations matched the description of Nishida et al. (1999). E. Wroblewski observed four additional ant-fishing sessions between 2006 and 2007, including one by Dilly (DL; who W. Wallauer observed to fish in 1999 but who was clearly inexperienced at that time) and two sessions by Titan (TN) and Tarzan (TZN), Patti's offspring.

Table 1.

Camponotus Predation in Kasekela before 2008

| Date | Camponotus predators | Session duration (min)a | Species | Ant fishing? | Comments | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sept. 20, 1978 | PI, WK, WI | <15 | Camponotus brutus (?) | Yes | PI, WK, and WI feed on “large, fierce” red and black ants from a tree hole. WK and WL use tools; it is not clear whether PI does. | B-record |

| Mar. 2, 1994 | FS | Several | Unknownb | Yes | First recorded case of tool-assisted Camponotus predation in the Kasekela community since the 1978 observation. FS appears fully proficient. | WW |

| Aug. 5, 1995 | SR | <1 | Unknown | … | SR reaches into large hole with bare hand for ants. | WW |

| Mar. 10, 1997 | GD | <1 | Unknownb | Yes | GD fishes for ants in rotten wood but is unsuccessful. Both Camponotus and Macrotermes visible on surface. | WW |

| Jan. 5, 1998 | FEc | <1 | Unknown | Yes | Tree is hollow, and no ants are visible. FE gives up on fishing in holes and digs into soil and chaff inside tree but collects no ants. | WW |

| Mar. 12, 1999 | DL, FO, GD, JK, TZ, ZS | >15 | Unknownb | Yes | TZ fishes proficiently before filming begins. FO also attempts to fish; not clear whether successful. ZS, JK, DL, and GD appear interested in ants (JK eats several), but all (except for TZ) appear unskilled and uncertain. DL makes and attempts to use massive tool that appears completely inappropriate for task. | WW |

| Feb. 16, 2001 | KS, SI, SN, SR | >80 | Camponotus chrysurus | Yes | Numerous fishing bouts occur in two trees at Hilltop. KS, SI, and SR are all proficient and acquire ants. SN uses no tools but appears to eat ants off the tree. | WW |

| Dec. 11, 2001 | GA | Several | Unknownb | Yes | GA moves up and down tree trunk and fishes proficiently at several holes. | WW |

| Sept. 5, 2002 | PI, TN | 22 | Unknown | Unknown | Feeding on ants in tree. Not clear whether tools were used. | B-record |

| Oct. 15, 2003 | BAH, SA, SI, SN, SR, TB | >5 | Unknownb | See comments | BAH makes tool but does not use it. SA immediately attacks BAH and drives her away. No other tools made or used; targets are handfuls of alates and brood in rotten wood that is easily broken apart by hand. SW closely observes the others but consumes no ants. | WW |

| Jan. 22, 2005 | BAH, NUR | Several | Unknownb | Yes | BAH appears proficient and confident, though she attempts to force thick tool into small hole, perhaps in an effort to widen it. BAH observed closely by SAM. | WW |

| Oct. 9, 2005 | GLI | Several | Unknown | Yes | Alternately eats fruit and fishes for ants. | B-record |

| Feb. 10, 2006 | DL | Unclear | Unknown | Yes | DL perches on tree trunk and probes into the hollow of the tree for ants with a tool. | EW |

| June 13, 2006 | FLI | Unclear | Unknown | Yes | FLI uses a stick to probe into tree hole for insects, almost certainly ants. | EW |

| Feb. 20, 2007 | TN, TZN | <20 | Unknown | Yes | TN fishes for several minutes in a tree. TZN moves into his position immediately when TN leaves. TZN is interrupted by a display by TB. | EW |

| Mar. 19, 2007 | TN, TZN | <5 | Unknown | Yes | TN fishes for several minutes in a tree. TZN moves into his position immediately when TN leaves. TZN stops when group moves on. | EW |

Note. See table 3 for animal IDs. WW = W. Wallauer; EW = E. Wroblewski.

Because many sessions were not recorded from start to finish, we can provide only estimates of their durations based on the video time stamps and/or accompanying notes.

Prey is Camponotus chrysurus, Camponotus vividus, or Camponotus sp. 1, based on examination of video records.

Though we list him as a Camponotus predator, FE was never observed to successfully acquire ants.

Field assistants confirmed in interviews that Camponotus predation was not observed in Kasekela until the mid-1990s (I. Salala, personal communication). In a review of the digitized B-record (1974–2007) and translated narrative notes (1995–2007) for the Kasekela community, R. C. O'Malley and C. M. Murray found only two additional unambiguous records of Camponotus consumption (one session per 22,540 observation hours). In one 2002 observation, Patti and Titan fed on Camponotus ants for 22 minutes—almost 25 years after Patti was last observed to do so. The record did not specify whether tools were used. The low observation frequency suggests that even after the first documented appearance in 1994, Camponotus predation remained rare (or at least remained rare among focal targets, which are a subset of habituated Kasekela adults).

2008–2010 Observations

During 1,608.5 contact hours in 2008–2010, R. C. O'Malley observed 20 predation sessions on Camponotus ants (one session per 80.4 observation hours; table 2). Three species (sub-genus Myrmopelta; Camponotus chrysurus, Camponotus vividus, and Camponotus sp. 1) were consumed. Half (10/20) of the sessions occurred at one stand of Brachystegia (miombo)-dominated woodland, locally called “Hilltop,” in the central Kasekela range (fig. 1). Of these Hilltop sessions, nine included fishing at a particular Anisophyllea pomifera (mshindwi) tree. Other sessions included another Anisophyllea and a Brachystegia, both within 30 m of the favored tree. In all, 13/20 (65%) of sessions included fishing at Anisophyllea trees. Nishida and Hiraiwa (1982) reported that ant fishing at Mahale is largely an arboreal activity (110/125, 88% of bouts). In contrast, participants were entirely terrestrial in 7/18 (38.9%) of the Kasekela sessions observed in their entirety. In only four sessions (22.2%) did participants remain entirely arboreal (though the ants were always arboreal). This may simply reflect the location of access holes. For example, the favored Hilltop Anisophyllea tree had at least six holes <2 m high, but few were visible higher up the trunk.

Table 2.

Camponotus Predation in Kasekela Observed by R. C. O'Malley (2008-2010)

| Date | Predators | Session duration (hounmin) | Prey species | Ant fishing? | Hilltop? | Tree species | Completely arboreal? | Completely terrestrial? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feb. 21, 2008 | FU, FND, SN | 0:24 | Camponotus chrysurus | Yes | Yes | Anisophyllea pomifera a | … | Yes |

| Feb. 26, 2008 | DIA, DL | 0:12 | C. chrysurus | Yes | Yes | A. pomifera a | … | … |

| Feb. 26, 2008 | EZA, TZN | 0:18 | C. chrysurus | Yes | Yes | A. pomifera | … | Yes |

| Mar. 29, 2008 | SAM | NR | Camponotus sp. 1 | Yes | … | A. pomifera | … | Unclear |

| Apr. 2, 2008 | TZN | NR | Camponotus sp. 1 | Yes | … | Combretum molle and Brachystegia sp. | … | Unclear |

| Sept. 12, 2008 | TZN | 0:01 | C. chrysurus b | Yes | Yes | A. pomifera a | … | Yes |

| Sept. 16, 2008 | MAK, TG, TOM, ZEL | 0:32 | C. chrysurus | Yes | Yes | A. pomifera a | … | … |

| Oct. 5, 2008 | GLD, IMA | 0:09 | C. chrysurus | Yes | … | A. pomifera | Yes | … |

| Oct. 21, 2008 | NUR | 0:01 | C. chrysurus | … | … | Ficus sp. | … | Yes |

| Oct. 22, 2008 | TZN | 0:02 | C. chrysurus | Yes | Yes | A. pomifera a | … | Yes |

| Oct. 26, 2008 | FLI, GLD, TZN | 0:11 | C. chrysurus | Yes | Yes | A. pomiferaa and Brachystegia sp. | … | … |

| Oct. 28, 2008 | TG, TOM | 0:01 | No sample | Yes | … | Albizia glabberima | Yes | … |

| Nov. 8, 2008 | TZN, ZL | 0:08 | C. chrysurus | Yes | Yes | A. pomiferaa and Brachystegia sp. | … | … |

| Jan. 5, 2009 | TOM, TZN | 0:01 | Camponotus vividus | … | … | A. pomifera | Yes | … |

| Jan. 5, 2009 | TOM | 0:01 | C. chrysurus | Yes | … | C. molle | … | … |

| Oct. 21, 2009 | FLI | 0:01 | C. chrysurus | … | … | Unknown (fallen log) | … | Yes |

| Oct. 26, 2009 | TZN, FU, GLD | 0:01 | Camponotus sp. 1 | Yes | … | Unknown | … | Yes |

| Nov. 7, 2009 | ERI, EZA, FU, NAS, SI, TZN | 2:02 | C. chrysurus | Yes | Yes | A. pomifera a | … | … |

| Nov. 22, 2009 | FAM | 0:05 | C. chrysurus | Yes | … | Unknown | Yes | … |

| Feb. 9, 2010 | BAH, BRZ, FU, GIM, GLD, GA | 0:23 | C. chrysurus | Yes | Yes | A. pomiferaa and Brachystegia sp. | … | … |

Note. See table 3 for animal IDs. NR = not recorded.

Favored A. pomifera tree at Hilltop.

No ants were consumed in this session.

Figure 1.

Map of Gombe National Park, showing the 2008 Kasekela community range and the locations of Camponotus predation sessions during the 2008–2010 study period.

Seventeen of the 20 sessions involved tools in the form of ant fishing (figs. 2, 3). The three that did not were <1 min in length and appeared exploratory, though in two cases a few ants were consumed. Chimpanzees that did not use tools in these sessions were all seen to ant fish at other times. Tools were fashioned from grass, twigs, or leaf midribs from nearby vegetation, leaf litter, or the host tree. The recovered tools ranged in length from 6 to 40 cm (mean = 23.17, median = 24, n = 9) though were usually trimmed down over the course of a session as they became bent or frayed.

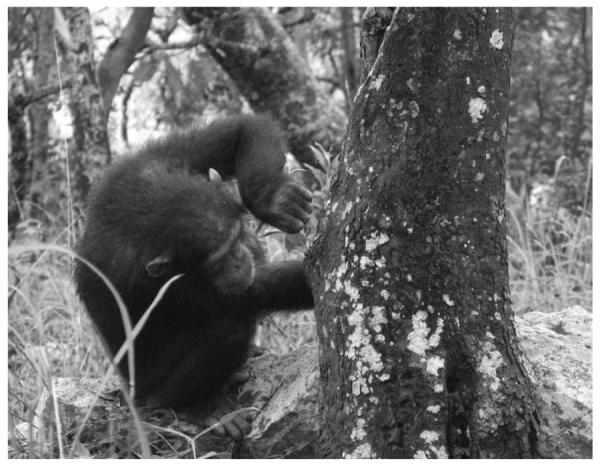

Figure 2.

Ant fishing by an adolescent male chimpanzee in 2008.

Figure 3.

Ant fishing at the favored Anisophyllea pomifera tree at Hilltop in 2010.

The 18 predation sessions observed from start to finish lasted from <1 to 122 min (sessions <1 min scored as 1 min; mean = 15:10 min, median = 6:30 min). Sessions involved up to six participants (mean = 2.25, median = 2). Typically one or two chimpanzees fed at once. In 3/12 sessions involving multiple chimpanzees, adolescents were seen to displace younger chimpanzees from fishing spots, but no aggression was observed among adult females. Mature adult males (≥15 years old) were never observed to prey on Camponotus or to show interest when others did so.

Kasekela chimpanzees were discriminating in their choice of Camponotus prey. R. C. O'Malley observed them pass up three opportunities to consume C. brutus. In October 2008, a large mixed-sex party (including 13 known Camponotus predators) encountered a fallen log on a trail that was swarming with C. brutus soldiers. Every chimpanzee passed directly over the ant-covered log without showing any interest whatsoever. In November 2008, an immature female, Golden (GLD), her twin sister, Glitter (GLI), and their mother, Gremlin (GM) encountered C. brutus infesting the bark of a tree and the surrounding leaf litter. Glitter and Gremlin passed by without interest, but Golden tugged at the bark and stirred the leaf litter with her hands to provoke the ants and then rolled on her back among them for several seconds before moving on. We hypothesize that she was attracted by the ants' strong citrus smell. Also in November 2008, a mixed-sex party, including four known Camponotus predators, used tools to scrape honey and comb from a stingless bee nest (probably Hypotrigona) for 2 min in a fallen tree that also hosted a C. brutus nest. The chimpanzees were forced to constantly reposition themselves to avoid the swarming ant soldiers while feeding. Though Camponotus maculatus are abundant in the Kasekela community range (O'Malley 2011), R. C. O'Malley observed no interactions between chimpanzees and this species.

Spread of Camponotus Predation in Kasekela

We compiled a list of known Camponotus predators in the Kasekela community (table 3) and summarized these data in 5-year increments from 1990 to February 2010 (fig. 4). Apart from the single confirmed observation in 1978 (Goodall 1986), we found no unambiguous records of Camponotus predation in Kasekela before 1994. By February 2010 a majority of living community members over 2 years old (33/57, or 57.9%, with four infants excluded) had preyed on Camponotus. Most Camponotus predators (31/33, 93.9%) were ant fishers. In less than 2 decades, ant fishing had become a customary behavior in Kasekela, though it was considered absent for decades. Interestingly, with three exceptions—Wilkie, who fished for Camponotus with Winkle and Patti in 1978 but never did again, and Tubi (TB) and Sandi (SA), who consumed Camponotus without tools in 2003 but never did again—all known Camponotus predators were either individuals born in the Kasekela community after 1981 (28/52, or 53.8%, of Kasekela-born chimpanzees who reached at least 2 years of age) or immigrant females (9/37, or 24.3%; fig. 5).

Table 3.

List of Known Camponotus Predators in the Kasekela Community

| Name | ID | Sex | Natal community | Birth yeara | Year emigrated to Kasekela | Mother | Years Camponotus predation observed | Seen to ant fish? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winkle | WK | F | ? | 1958 | 1968 | ? | 1978 | Yes |

| Patti | PI | F | ? | 1961 | 1971 | ? | 1978, 2002 | Unclear |

| Wilkie | WL | M | … | 1972 | … | WK | 1978 | Yes |

| Sandi | SA | F | … | 1973 | … | SW | 2003 | … |

| Tubi | TB | M | … | 1977 | … | LB | 2003 | … |

| Trezia | TZ | F | Mitumba | 1978 | 1991 | TRU | 1999b | Yes |

| Kris | KS | M | … | 1982 | … | KD | 2001 | Yes |

| Flossi | FS | F | … | 1985 | … | FF | 1994 | Yes |

| Dilly | DL | F | … | 1986 | … | DM | 1999, 2006, 2008 | Yes |

| Galahad | GD | M | … | 1988 | … | GM | 1997, 1999 | Yes |

| Bahati | BAH | F | Mitumba | 1988 | 2001 | BAR | 2003,b 2005, 2010 | Yes |

| Nasa | NAS | F | Kalande | 1988 | 2000 | ? | 2009 | Yes |

| Tanga | TG | F | … | 1989 | … | PI | 2008 | Yes |

| Faustino | FO | M | … | 1989 | … | FF | 1999 | Yes |

| Malaika | MAK | F | Kalande | 1989 | 2002 | HAI (?) | 2008 | Yes |

| Jackson | JK | M | … | 1989 | … | JF | 1999 | Unclear |

| Nuru | NUR | F | Kalande | 1990 | 2002 | ? | 2005, 2008 | Yes |

| Sherehe | SR | F | … | 1991 | … | SA | 1995, 2001, 2003 | Yes |

| Schweini | SI | F | … | 1991 | … | SW | 2001,2003, 2009 | Yes |

| Eliza | EZA | F | Kalande | 1992 | 2004 | ? | 2008, 2009 | Yes |

| Imani | IMA | F | Kalande | 1992 | 2005 | ECO | 2008 | Yes |

| Ferdinand | FE | M | … | 1992 | … | FF | 1998c | Yes |

| Gaia | GA | F | … | 1993 | … | GM | 2001, 2010 | Yes |

| Zeus | ZS | M | … | 1993 | … | TZ | 1999 | Yes |

| Titan | TN | M | … | 1994 | … | PI | 2002, 2007 | Yes |

| Sampson | SN | M | … | 1996 | … | SA | 2001, 2003, 2008 | Yes |

| Fudge | FU | M | … | 1996 | … | FN | 2008, 2009, 2010 | Yes |

| Golden | GLD | F | … | 1998 | … | GM | 2008, 2009, 2010 | Yes |

| Glitter | GLI | F | … | 1998 | … | GM | 2005 | Yes |

| Flirt | FLI | F | … | 1998 | … | FF | 2006, 2008, 2009 | Yes |

| Tarzan | TZN | M | … | 1999 | … | PI | 2007, 2008, 2009 | Yes |

| Zella | ZEL | F | … | 1999 | … | TZ | 2008 | Yes |

| Fundi | FND | M | … | 2000 | … | FN | 2008 | Yes |

| Tom | TOM | M | … | 2001 | … | TG | 2008, 2009 | Yes |

| Samwise | SAM | F | … | 2001 | … | SA | 2008 | Yes |

| Gimli | GIM | M | … | 2004 | … | GM | 2010 | Yes |

| Familia | FAM | F | … | 2004 | … | FN | 2009 | Yes |

| Baroza | BRZ | M | … | 2005 | … | BAH | 2010 | Yes |

| Diaz | DIA | F | … | 2005 | … | DL | 2008 | Yes |

| Eriki | ERI | M | … | 2007 | … | EZA | 2009 | Yes |

Note. F = female; M = male.

Birth year is estimated for some immigrant individuals.

Trezia and Bahati are presumed to have already been proficient in ant fishing in Mitumba before transferring into Kasekela, though no specific observations are available.

Unsuccessful attempt. Though we list him as a Camponotus predator, Ferdinand was never observed to successfully acquire ants.

Figure 4.

Spread of Camponotus predation in the Kasekela community between 1990 and 2010. The suspected Camponotus predator in 1995 is Trezia.

Figure 5.

Known Camponotus predators in the Kasekela community (in white), sorted by immigration status and age. These demographic counts exclude individuals who died at <2 years old or who were <2 years old in February 2010, since they are likely too young to have exhibited the behavior.

Camponotus Predation in Mitumba

Mitumba field assistants working during the late 1980s and early 1990s confirmed in interviews that ant fishing was habitual in Mitumba since observations began (T. Mikidadi and G. Paulo, personal communication), and the behavior was observed by W. Wallauer in 1992. Unfortunately, specific feeding records are unavailable before late 2001. R. C. O'Malley identified 47 sessions of Camponotus consumption (almost always with tools, according to field assistant interviews) by 10 different chimpanzees (one session per 344 observation hours) in the Mitumba B-record (late 2001–2007). In contrast to Kasekela, adult males in Mitumba prey on Camponotus ants (in 7/47 sessions, 14.9%). Though the session rate for Mitumba was lower than that observed in the Kasekela community during the 2008–2010 study periods, the Mitumba total includes only focal target sessions, whereas the Kasekela rate includes sessions by both focal and nonfocal chimpanzees. Interestingly, there were more observations of Camponotus predation by Flossi than for any other Mitumba chimpanzee (13/47 sessions, 27.7%), although she was also the most frequently followed adult female. In addition to C. chrysurus and C. vividus, Mitumba chimpanzees also prey on C. brutus (T. Mikidadi and G. Paulo, personal communication).

Discussion

How did Camponotus predation become a customary behavior in the Kasekela community? We posit three (not necessarily exclusive) hypotheses.

-

Hypothesis 1. Predation on Camponotus was already practiced within the Kasekela community but became more frequent due to changes in insect prey availability or other environmental factors.

One possibility is that Camponotus ant predation did occur (albeit rarely) in Kasekela during the first 3 decades of research. As discussed above, Goodall's (1986) report on “other ants” included one likely case of Camponotus brutus predation in 1978. The list of ant-fishing predation sessions before 2008 (table 1) probably underestimates its actual prevalence in the community, particularly after 1994. However, of the three participants in the 1978 session, only Patti was ever seen to subsequently eat Camponotus and then only in a single session more than 2 decades later, despite being a regular focal target in intervening years. Also, C. brutus were not consumed in the 1994–2007 observations or in the 2008–2010 study periods.

Though insect prey consumed by Gombe chimpanzees have been collected previously (Collins and McGrew 1987; Schöning et al. 2008), no data are available to assess whether Camponotus have become more common over time. However, it is known that Gombe has undergone considerable environmental change since research began in 1960. Pintea (2007) found that between 1972 and 1999, canopy cover increased within the park (reflecting an increase in woodland, mature forest, and vines). Ant diversity is a useful bioindicator in land management efforts because ants are ubiquitous, abundant, and sensitive to habitat change (Andersen and Majer 2004). Previously absent or rare ant species may have become more common since the 1960s (or, conversely, common species may have become rarer) due to habitat changes and a reduced human footprint within the park.

Anecdotally, another ant species consumed by Kasekela chimpanzees appears to have become less common within Gombe. In a recent transect survey of social insects in the Mitumba and Kasekela community ranges, weaver ants (Oecophylla longinoda) were not encountered at all (O'Malley 2011), though they were collected ad lib. These ants were long considered abundant in Gombe (D. A. Collins, personal communication) and remained abundant outside the park boundaries (S. Pindu, personal communication). Oecophylla is a particularly aggressive and territorial ant genus, and colonies are cultivated by humans in some parts of Africa and Asia to control more destructive insects, including Camponotus (Hölldobler and Wilson 1990; Room 1971; van Mele 2008). Oecophylla was the most commonly detected insect prey in an analysis of Gombe fecal samples in 1964–1965 (McGrew 1979), but R. C. O'Malley observed Oecophylla predation only twice during the 2008–2010 study period (R. C. O'Malley, unpublished data). A review of the long-term Kasekela data set found that consumption frequency of Oecophylla has declined since 1974 (R. C. O'Malley and C. M. Murray, unpublished data). Whether this is due to a decline in these ants' abundance or for some other reason is unknown. However, Room (1971) found that the presence of O. longinoda was negatively correlated with several species of Camponotus, including Camponotus chrysurus and Camponotus vividus, in Ghanan cocoa farms. Though Oecophylla colonies can effectively dominate other ant genera in cultivated landscapes (Leston 1970, 1973; Majer 1976; van Mele 2008), they may be less effective at dominating ant communities in mature secondary or partially disturbed forests. Such forests often have high ecological and microhabitat complexity and show correspondingly high arthropod species richness (Agosti et al. 2000; Andow 1991; Dejean et al. 2000).

The environmental regeneration within Gombe since the 1970s may indeed be linked to a decline in O. longinoda and a corresponding increase in Camponotus abundance, which in turn might have made consumption of Camponotus more appealing or likely for Kasekela chimpanzees. However, the single observation of predation on C. brutus over many decades of focal observation is insufficient evidence to conclude that Camponotus predation regularly occurred in Kasekela before the 1990s. Furthermore, the spread of Camponotus predation almost exclusively among younger cohorts and immigrants after 1994 is inconsistent with a purely ecological explanation. Except for the 1978 session involving Wilkie and the single 2003 session involving Sandi and Tubi, only native Kasekela chimpanzees born after 1981 and immigrant females have been observed to consume Camponotus.

-

Hypothesis 2. Predation on Camponotus was an innovation by a native Kasekela chimpanzee.

A native Kasekela chimpanzee (most likely Flossi) may have independently discovered that Camponotus were edible and could be acquired through the use of tools. This novel behavior could then have spread via social learning within the community, in a manner reminiscent of the spread of sweet potato washing and other food-processing traditions among the macaques of Koshima Island (Kawai 1965) or hand-clasp grooming among Yerkes chimpanzees (de Waal and Seres 1997). Wild chimpanzees (particularly immature individuals) closely observe conspecifics in feeding contexts (Goodall 1986; Lonsdorf 2005, 2006; McGrew 1977). Use of tools to acquire insects is widespread among wild chimpanzees (McGrew 1992; Whiten et al. 1999, 2001). During the 2008–2010 study period, two individuals <3 years old, Eric (ERI) and Diaz (DIA), were seen to successfully ant fish, suggesting that this is not a difficult skill to acquire. Furthermore, C. chrysurus, C. vividus, and Camponotus sp. 1 can all be acquired without tools and without threat of injury. Other favored insect prey for chimpanzees such as Dorylus, Apis, Macrotermes soldiers, or C. brutus soldiers can all draw blood or inflict pain on a hominoid predator (R. C. O'Malley, personal observation).

We cannot rule out that Flossi or some other Kasekela chimpanzee discovered Camponotus predation independently. However, by the time of Flossi's first ant-fishing observation in 1994, at least one immigrant from the ant-fishing Mitumba community was present in Kasekela who could have served as a skilled model.

-

Hypothesis 3. Predation on Camponotus was introduced to the Kasekela community by an immigrant female.

Camponotus predation with tools was habitual in the Mitumba community during the 1980s and early 1990s, though specific practitioners are not known. A Mitumba female, Trezia (TZ), emigrated to Kasekela in 1991. We hypothesize that she was among these proficient ant fishers observed in prior years at Mitumba. There is circumstantial evidence to support this: in Kasekela, Trezia was (excluding the participants in the 1978 session) the first adult female observed to ant fish proficiently and the only adult chimpanzee seen to consume Camponotus in Kasekela prior to 2003. In that year, Bahati (BAH), another Mitumba immigrant who arrived in 2001, attempted to do so before being supplanted by Sandi and others (table 3). Females immigrants in Kasekela often remain somewhat peripheral (and low ranking) in the community for years due to intense competition with resident females (and perhaps wariness of human observers). Trezia ascended the female dominance hierarchy more quickly than most immigrants and was not skittish around other chimpanzees (C. M. Murray, unpublished data; Murray, Eberly, and Pusey 2006). This may have made her a viable model for younger cohorts. Interestingly, two other Mitumba immigrants (Vanilla [VAN] in 2006 and Rumumba [RUM] in 2008) emigrated to Kasekela after Trezia and Bahati, though we found no record of these females consuming Camponotus in either community. However, neither female was a frequent focal target in Mitumba or Kasekela.

As noted above, even if environmental changes within Gombe affected the ant community in such a way as to make Camponotus predation more appealing or likely, this fails to explain why the behavior is nearly exclusive to immigrants and younger Kasekela cohorts. Given the presence of Trezia in the community by 1991 and Flossi's apparent proficiency in the first recorded observation, it is at least as likely that Flossi learned the behavior by observing Trezia before March 1994 rather than inventing it herself. While we cannot completely rule out the innovation hypothesis for the appearance and spread of ant fishing, we believe that the circumstantial evidence favors introduction by Trezia.

Why did ant fishing become customary in the Kasekela community when many novel behaviors that appear in chimpanzee communities fail to do so (Nishida, Matsusaka, and McGrew 2009)? We hypothesize that in addition to environmental changes within Gombe, the specific characteristics of the Hilltop site where the majority of sessions occurred in 2008–2010 contributed to the establishment of ant fishing in Kasekela. These include the following:

Relaxed social context. During the 2008–2010 study periods, Hilltop was a favored resting spot for Kasekela chimpanzees (R. C. O'Malley, unpublished data). After arriving at Hilltop, adults would often stop to rest or engage in grooming bouts lasting up to several hours. Younger individuals would typically rest, groom, or play.

Frequent visits. Hilltop lies in the central Kasekela community range (fig. 1) and has been a popular resting place for the community since the 1970s (W. C. McGrew, personal communication). Chimpanzee parties passed through this area up to several times a week during the 2008–2010 field seasons (R. C. O'Malley, unpublished data).

Open habitat. The Hilltop habitat is miombo woodland (Collins and McGrew 1988). The altitude (~1,134 m) and presence of mature Brachystegia trees mean that the area is cool and at least partially shaded year-round. Ground-level vegetation is limited to scattered shrubs and grasses. Observation conditions for both humans and chimpanzees are ideal.

Multiple predictable fishing sites in proximity. In 2001, W. Wallauer observed Kasekela chimpanzees fishing at both the favored Hilltop Anisophyllea tree and a nearby Brachystegia tree. Nine of the 20 sessions observed in the 2008–2010 field season involved at least one of these two trees, suggesting that both have been productive ant-fishing sites for at least 11 years. A second Anisophyllea tree within 30 m was also fished in 2008. The favored Anisophyllea tree at Hilltop had at least six fishing holes <2 m from the ground, although not all holes appeared to be productive during every visit. This allowed up to three chimpanzees to fish together simultaneously.

The conditions at Hilltop may also partially explain why C. brutus and C. maculatus are not consumed by Kasekela chimpanzees, despite their availability within the community range (O'Malley 2011). If most opportunities to observe Camponotus predation have occurred when C. chrysurus were targeted, these two larger Camponotus species may not be recognized as potential food. Predation on these larger and more aggressive ants also brings some risk of injury, enough to curtail or deter chimpanzee predation (e.g., Nishida and Hiraiwa 1982:76) and so may also require a more skilled technique.

Other researchers have noted that although novel behaviors appear frequently in chimpanzee communities, many fail to become established in a community's repertoire (Biro et al. 2003; Boesch 1995; Nishida, Matsusaka, and McGrew 2009). In discussing the implications of their nut introduction experiments at Bossou, Biro et al. (2003:221) concluded that chimpanzees tended to pay attention to the tool-using activities of conspecifics of similar age or older, but not younger, than themselves. They concluded that the presence of a “reliable model” (an adult “keenly engaged in the handling of an unfamiliar object”) is necessary for the establishment and propagation of novel behaviors. In their experiments, the presence of the immigrant Yo was a clear catalyst for other chimpanzees to investigate unfamiliar nuts. The authors further hypothesized that cultural innovations in chimpanzees should be expected to propagate horizontally (within age cohorts) or vertically downward (from mother to offspring or from juvenile to infant) but not vertically upward (from younger to older individuals). Whether ant fishing in Kasekela arose through innovation or appeared through introduction, the pattern of practitioners is consistent with Biro et al.'s (2003) model.

In summary, Camponotus predation in any form was (at best) extremely rare in the Kasekela community during the first 3 decades of observation. Camponotus predation, almost always in the form of ant fishing, was observed with increasing frequency beginning in the mid-1990s. Ant fishing is now a customary behavior in Kasekela. This behavior appeared and spread in the years after the immigration of a female from the Mitumba community, where ant fishing was habitual. With only three exceptions, all known Camponotus predators (and with one exception, all known ant fishers) are either Kasekela natives born after 1981 or immigrant females. While environmental changes in Gombe may have influenced the abundance and distribution of potential ant prey, such changes are insufficient to explain why ant fishing has spread almost exclusively among immigrants and younger Kasekela cohorts. Though innovation by a Kasekela native cannot be completely ruled out, the circumstantial evidence suggests that ant fishing was introduced via immigration. We hypothesize that the Hilltop site provided an environment that was extremely conducive to acquiring this novel behavior.

Chimpanzee communities in similar habitats, and even neighboring communities with documented female transfer between them, do not necessarily demonstrate similar behavior patterns (Biro et al. 2003; McGrew 1992; McGrew et al. 2001; Nakamura and Uehara 2004). Nevertheless, Kamilar and Marshack (2012) found that geography (specifically, longitude) but not ecology was a significant predictor of cultural similarity among long-term chimpanzee study communities, highlighting the potential role of cultural transmission in explaining intercommunity behavioral variation. The observations reported here support the potential importance of subtle (and even site-specific) environmental factors in the spread of novel behaviors.

To our knowledge, apart from the Bossou nut-cracking experiments, no example of a cultural behavior successfully spreading from one community to another has previously been reported in wild chimpanzees. As noted by McGrew (2004), the increasing fragmentation of chimpanzee habitat will limit opportunities for the transmission of social as well as genetic information between communities. Still, though the three Gombe communities remain isolated from other populations, the possibility for cultural transmission and divergence within the population remains.

Acknowledgments

The Tanzania Commission for Science and Technology, the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute, Tanzania National Parks, and Gombe National Park granted permission to conduct research at Gombe. We thank the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI)–Tanzania for logistical support, particularly D. A. Collins, S. Kamenya, and A. Mosser. Emily Wroblewski generously shared her records of ant fishing. A. Pusey, I. Gilby, and A. Sandel provided access to the long-term Gombe records compiled at the JGI Center for Primate Studies at the University of Minnesota and, subsequently, the JGI Research Center at Duke University. A. Pusey, C. Stanford, M. Nakamura, and W. C. McGrew provided helpful comments. C. Schöning and F. H. Garcia assisted with ant identifications. R. C. O'Malley's fieldwork was supported by the University of Southern California. C. M. Murray's research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant 5R00HD057992-04). This paper is dedicated to the late Hilali Matama.

References Cited

- Agosti D, Majer JD, Alonso LE, Schultz TR. Ants: standard methods for measuring and monitoring biodiversity. Smithsonian Institution; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann J. Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour. 1974;49:227–267. doi: 10.1163/156853974x00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen AN, Majer JD. Ants show the way down under: invertebrates as bioindicators in land management. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2004;2:291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Andow DA. Vegetation diversity and arthropod population response. Annual Review of Entomology. 1991;36:561–586. [Google Scholar]

- Biro D. Clues to culture? the Coula and Panda-nut experiments. In: Matsuzawa T, Humle T, Sugiyama Y, editors. The chimpanzees of Bossou and Nimba. Springer; Tokyo: 2011. pp. 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Biro D, Inoue-Nakamura N, Tonooka R, Yamakoshi G, Sousa C, Matsuzawa T. Cultural innovation and transmission of tool use in wild chimpanzees: evidence from field experiments. Animal Cognition. 2003;6:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10071-003-0183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesch C. Innovation in wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) International Journal of Primatology. 1995;16:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie KE, de Waal FBM. Affiliation promotes the transmission of a social custom: handclasp grooming among captive chimpanzees. Primates. 2006;47:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s10329-005-0141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G, Laland KN. Social learning in fishes: a review. Fish and Fisheries. 2003;4:280–288. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne RW, Barnard PJ, Davidson I, Janik VM, McGrew WC, Miklosi A, Wiessner P. Understanding culture across species. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2004;8:341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DA, McGrew WC. Termite fauna related to differences in tool-use between groups of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Primates. 1987;28:457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Collins DA, McGrew WC. Habitats of three groups of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in western Tanzania compared. Journal of Human Evolution. 1988;17:553–574. [Google Scholar]

- DeJean A, McKey D, Gibernau M, Belin M. The arboreal ant mosaic in a Cameroonian rainforest (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Sociobiology. 2000;35:403–423. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FBM, Seres M. Propagation of handclasp grooming among captive chimpanzees. American Journal of Primatology. 1997;43:339–346. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1997)43:4<339::AID-AJP5>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler A, Sommer V. Subsistence technology of Nigerian chimpanzees. International Journal of Primatology. 2007;28:997–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall J. The chimpanzees of Gombe. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hölldobler B, Wilson EO. The ants. Belknap; Cambridge, MA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Humle T. Ant dipping in chimpanzees: an example of how micro-ecological variables, tool use, and culture reflect the cognitive abilities of chimpanzees. In: Matsuzawa T, Tomonaga M, Tanaka M, editors. Cognitive development in chimpanzees. Springer; Tokyo: 2006. pp. 452–475. [Google Scholar]

- Kamilar JM, Marshack JL. Does geography or ecology best explain “cultural” variation among chimpanzee communities? Journal of Human Evolution. 2012;62:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai M. Newly-acquired pre-cultural behavior of the natural troop of Japanese monkeys on Koshima Islet. Primates. 1965;6:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyono M. Ant-eating behavior not accompanied by tool use among wild chimpanzees in Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania. Paper presented at the XXII Congress of the International Primatological Society; Edinburgh. Aug, 2008. pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Leston D. Entomology of the cocoa farm. Annual Review of Entomology. 1970;15:273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Leston D. The ant mosaic: tropical tree crops and the limiting of pests and diseases. Pest Articles and News Summaries. 1973;19:311–341. [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdorf EV. Sex differences in the development of termite-fishing skills in wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) of Gombe National Park, Tanzania. Animal Behaviour. 2005;70:673–683. [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdorf EV. The role of the mother in the acquisition of tool-use skills in wild chimpanzees. Animal Cognition. 2006;9:36–46. doi: 10.1007/s10071-005-0002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majer JD. The maintenance of the ant mosaic in Ghana cocoa farms. Journal of Applied Ecology. 1976;13:123–144. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew WC. Socialization and object manipulation in wild chimpanzees. In: Chevalier-Skolnikoff S, Poirier FE, editors. Primate bio-social development. Garland; New York: 1977. pp. 261–288. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew WC. Evolutionary implications of sex differences in chimpanzee predation and tool use. In: Hamburg DA, McCown ER, editors. The great apes. Benjamin/Cummings; Menlo Park, CA: 1979. pp. 440–463. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew WC. Chimpanzee material culture: implications for human evolution. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew WC. Culture in nonhuman primates? Annual Review of Anthropology. 1998;27:301–328. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew WC. The cultured chimpanzee: reflections on cultural primatology. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew WC, Marchant LF, Scott SE, Tutin CEG. Intergroup differences in a social custom of wild chimpanzees: the grooming hand-clasp of the Mahale Mountains, Tanzania. Current Anthropology. 2001;42:148–153. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew WC, Tutin CEG. Evidence for a social custom in wild chimpanzees? Man. 1978;13:234–251. [Google Scholar]

- Murray CM, Eberly LE, Pusey AE. Foraging strategies as a function of season and rank among wild female chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Behavioral Ecology. 2006;17:1020–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Uehara S. Proximate factors of different types of grooming-hand-clasp in Mahale chimpanzees: implications for chimpanzee social customs. Current Anthropology. 2004;45:108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T. The ant-gathering behavior by the use of tools among wild chimpanzees of the Mahali Mountains. Journal of Human Evolution. 1973;2:357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, Hiraiwa M. Natural history of a tool-using behaviour by wild chimpanzees in feeding upon wood-boring ants. Journal of Human Evolution. 1982;11:73–99. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, Kano T, Goodall J, McGrew WC, Nakamura M. Ethogram and ethnography of Mahale chimpanzees. Anthropological Science. 1999;107:141–188. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, Matsusaka T, McGrew WC. Emergence, propagation or disappearance of novel behavioral patterns in the habituated chimpanzees of Mahale: a review. Primates. 2009;50:23–36. doi: 10.1007/s10329-008-0109-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, Uehara S. Natural diet of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii): long-term record from the Mahale Mountains, Tanzania. African Study Monographs. 1983;3:109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Nishie H. Natural history of Camponotus ant-fishing by the M group chimpanzees at the Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania. Primates. 2011;52:329–342. doi: 10.1007/s10329-011-0270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi G, Matsuzawa T. Deactivation of snares by wild chimpanzees. Primates. 2011;52:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s10329-010-0212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley RC. PhD diss. Department of Biological Sciences, University of Southern California; Los Angeles: 2011. Environmental, nutritional and social aspects of insectivory by Gombe chimpanzees. [Google Scholar]

- Perry S, Baker M, Fedigan L, Gros-Louis J, Jack K, MacKinnon KC, Manson JH, Panger M, Pyle K, Rose L. Social conventions in wild white faced-capuchin monkeys: evidence for behavioral traditions in a Neotropical primate. Current Anthropology. 2003;44:241–268. [Google Scholar]

- Pintea L. PhD diss. Conservation Biology Graduate Program, University of Minnesota; Minneapolis: 2007. Applying remote sensing and GIS for chimpanzee habitat change detection, behavior and conservation. [Google Scholar]

- Pusey AE, Wilson ML, Collins DA. Human impacts, disease risk, and population dynamics in the chimpanzees of Gombe National Park, Tanzania. American Journal of Primatology. 2008;70:738–744. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendell L, Whitehead H. Culture in whales and dolphins. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2001;24:309–382. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x0100396x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room PM. The relative distributions of ant species in Ghana's cocoa farms. Journal of Animal Ecology. 1971;40:735–751. [Google Scholar]

- Schöning C, Humle T, Möbius Y, McGrew WC. The nature of culture: technological variation in chimpanzee predation on army ants revisited. Journal of Human Evolution. 2008;55:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A. On the insect-eating habits among wild chimpanzees living in the savanna woodland of western Tanzania. Primates. 1966;7:481–487. [Google Scholar]

- Tutin CEG, Fernandez M. Insect-eating by sympatric lowland gorillas (Gorilla g. gorilla) and chimpanzees (Pan t. troglodytes) in the Lope Reserve, Gabon. American Journal of Primatology. 1992;28:29–40. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350280103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara S. Sex and group differences in feeding on animals by wild chimpanzees in the Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania. Primates. 1986;27:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- van Mele P. A historical review of research on the weaver ant Oecophylla in biological control. Agricultural and Forest Entomology. 2008;10:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik CP, Ancrenaz M, Borgen G, Galdikas B, Knott CD, Singleton I, Suzuki A, Utami SS, Merrill M. Orangutan cultures and the evolution of material culture. Science. 2003;299:102–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1078004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, King AP, White DK. Discovering culture in birds: the role of learning and development. In: de Waal FBM, Tyack PL, editors. Animal social complexity: intelligence, culture and individualized societies. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2003. pp. 470–491. [Google Scholar]

- Whiten A, Goodall J, McGrew WC, Nishida T, Reynolds V, Sugiyama Y, Tutin CEG, Wrangham RW, Boesch C. Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature. 1999;399:682–685. doi: 10.1038/21415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiten A, Goodall J, McGrew WC, Nishida T, Reynolds V, Sugiyama Y, Tutin CEG, Wrangham RW, Boesch C. Charting cultural variation in chimpanzees. Behaviour. 2001;138:1481–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Whiten A, Horner V, de Waal FBM. Conformity to cultural norms of tool use in chimpanzees. Nature. 2005;437:737–740. doi: 10.1038/nature04047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiten A, Spiteri A, Horner V, Bonnie K, Lambeth S, Schapiro SJ, de Waal FBM. Transmission of multiple traditions within and between chimpanzee groups. Current Biology. 2007;17:1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S, Yamakoshi G, Humle T, Matsuzawa T. Invention and modification of a new tool use behavior: ant-fishing in trees by a wild chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) at Bossou, Guinea. American Journal of Primatology. 2008;70:699–702. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]