Abstract

Ergothioneine (5) and ovothiol (8) are two novel thiol-containing natural products. Their C-S bonds are formed by oxidative coupling reactions catalyzed by EgtB and OvoA enzymes, respectively. In this work, it was discovered that besides catalyzing the oxidative coupling between histidine and cysteine (1 → 6 conversion), OvoA can also catalyze a direct oxidative coupling between hercynine (2) and cysteine (2 → 4 conversion), which can shorten the ergothioneine biosynthetic pathway by two steps.

Sulfur is an important functional group in both primary and secondary metabolites. 1 Biological sulfur transfer reactions can make use of either an ionic or a radical-type of reaction mechanism. For example, the thioether formation in lantibiotic biosynthesis is an ionic type of reaction that is accomplished by having thiolates as the direct nucleophiles.2 Radical type C-S bond formation reactions are also well-documented.1a, 3 Some of the examples are: the incorporation of the thiol-functional groups into biotin,4 lipoate,3a thiamine pyrophosphate,5 molybdopterin cofactor,6 cofactor biogenesis in galactose oxidase, 7 tRNA nucleotide thiolmethylation, 8 and thiazolidine ring formation catalyzed by isopenicillin N synthase. 9 For sulfur transfer reactions, two types of activated sulfur species have also been discovered, 10 which are persulfides R-S-SH and thiocarboxylates R-CO-SH.

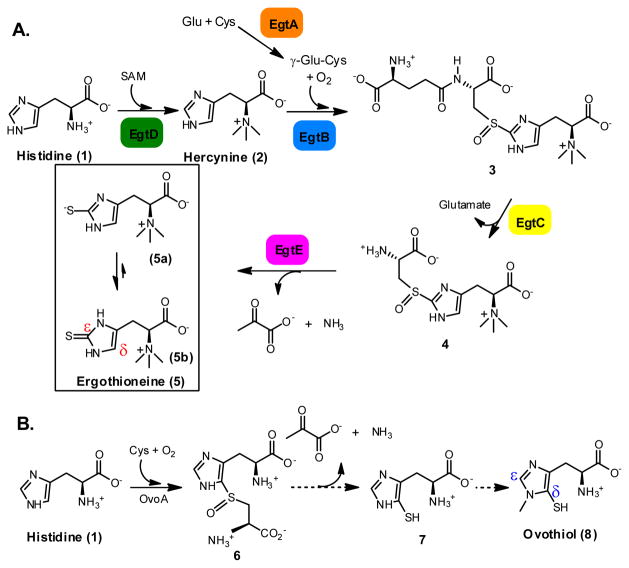

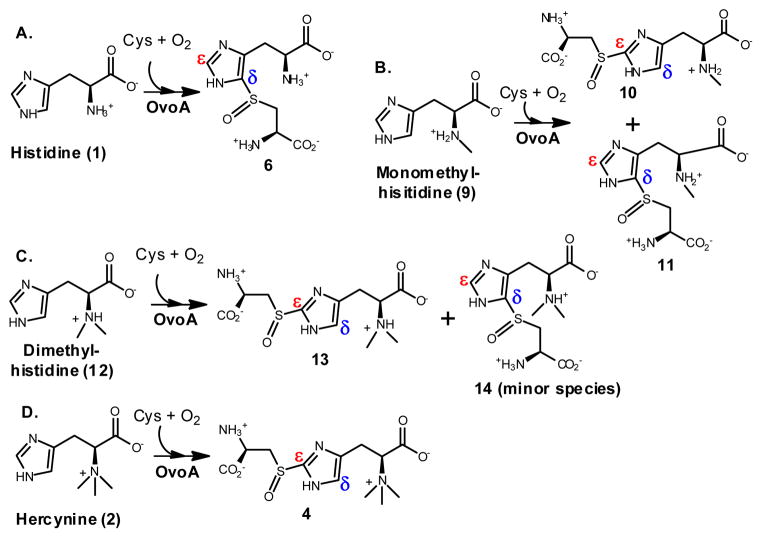

Ergothioneine (5) and ovothiol (8) are two thiol-imidazole containing natural products. Humans obtain ergothioneine from their diet and specifically enrich it in some tissues (e.g. liver, kidney, central nervous system and red blood cells) by using an ergothioneine-specific transporter.11 Ergothioneine’s beneficial effects to human health are due to its unusual redox property, which favors predominantly the thione form (5b, Scheme 1A) and makes ergothioneine much more stable than most other natural thiols.1c–d,11g Ergothioneine was isolated from ergot by Tanret in 1909, 12 and its biosynthetic gene cluster was reported by Seebeck in 2010 (Scheme 1A).13 Ergothioneine biosynthesis starts from histidine methylation to trimethylated histidine (hercynine, 2), which is then oxidatively coupled with γ-glutamylcysteine (γ-Glu-Cys) to 3. After glutamate is removed by hydrolysis, a PLP-containing enzyme (EgtE)-catalyzes the 4 → 5 conversion. Ovothiol is another thiol-histidine enriched in the eggs of many marine species. Ovothiol is proposed to be involved in H2O2 scavenging and facilitating the fertilization process14. For ovothiol biosynthesis (Scheme 1B), the only known enzyme is OvoA, which catalyzes the oxidative coupling between Cys and His (1 → 6 conversion). 15 Compare to ergothioneine, the C-S bond in ovothiol is at the δ instead of the ε position.

Scheme 1.

Proposed ergothioneine and ovothiol biosynthetic pathways.

Both EgtB and OvoA are mononuclear non-heme iron enzymes catalyzing four-electron oxidation processes (Scheme 1). However, EgtB and OvoA distinguish themselves from each other by their substrate preferences and product C-S bond regio-selectivity (Scheme 1). Ergothioneine’s thiol group is located at its imidazole ε-carbon, while ovothiol’s thiol group is at its imidazole δ-carbon. In addition, EgtB and OvoA use different substrates. EgtB catalyzes the oxidative coupling between hercynine (2) and γ-Glu-Cys while OvoA preferentially oxidatively couples His and Cys. In this report, a key factor governing OvoA-catalysis regio-selectivity was discovered. By systematically modulating the histidine methylation state, the OvoA-catalysis changes from OvoA-type of chemistry (1 → 6 conversion) to EgtB type of chemistry (2 → 4 conversion). Such a discovery can shorten the ergothioneine biosynthetic pathway by two steps.

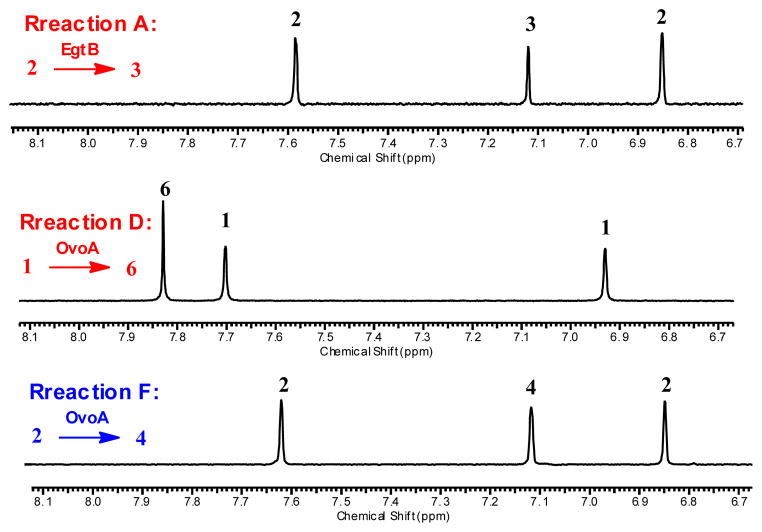

EgtB and OvoA were overexpressed in E. coli and purified anaerobically using Strep-tavidin affinity chromatography (Figure 1S). The purified proteins have close to stoichiometric amount of iron. To examine EgtB and OvoA substrate specificity, a 1H-NMR assay was utilized (Figure 1). In 1H-NMR spectrum, the chemical shifts of the EgtB product (3) imidazole H-atom, OvoA product (6) imidazole H-atom, and the substrate (histidine) are well-separated from the rest of the reaction mixture (Figure 1). Thus, the reaction mixture can be analyzed routinely without a need of the product separation (Figure 1). The signals with chemical shifts of 6.93 ppm and 7.70 ppm are assigned to the histidine imidazole H-atoms. The signal at 7.83 ppm is from the imidazole H-atom of ovothiol biosynthetic intermediate 6 (reaction D, Figure 1), while for the oxidative product 3 in ergothioneine biosynthesis, its imidazole H-atom has a chemical shift of 7.12 ppm (reaction A, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

1H-NMR assay (chemical shifts of imidazole ring H-atoms). Reaction A. Native EgtB reaction in ergothioneine biosynthesis. The chemical shift assignments are: 3: The imidazole H-atom of compound 3 (7.12 ppm); 2: The hercynine imidazole H-atoms (6.85, 7.58 ppm). Reaction D. Native OvoA reaction in ovothiol biosynthesis. The chemical shift assignments are: 6: The imidazole H-atom of compound 6 (7.83 ppm,); 1: The imidazole H-atoms of His (6.93, 7.70 ppm). Reaction F. A new OvoA reaction (oxidatively coupling between hercynine and Cys). In this case, the oxidative coupling product is compound 4, which has the EgtB type of regio-selectivity. Reaction list is shown in Scheme 2.

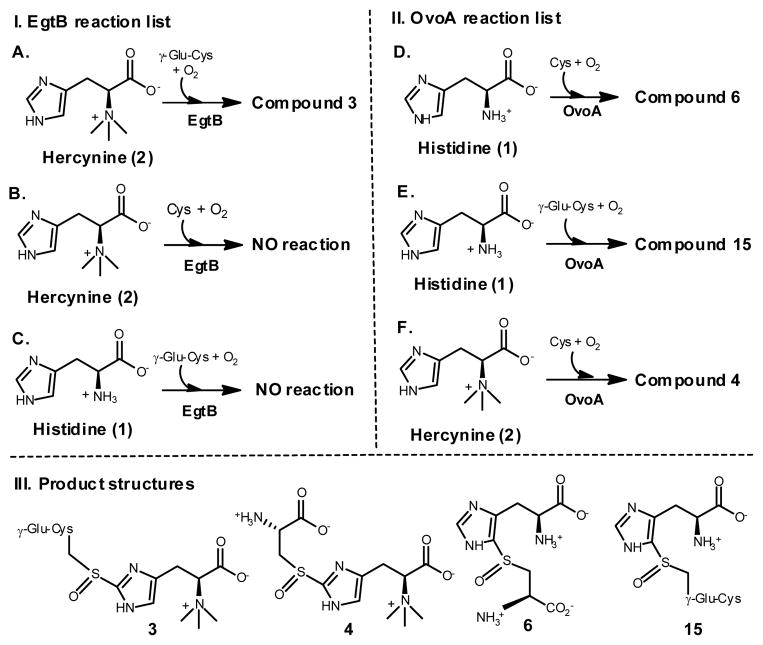

Using the 1H-NMR assay, we systematically examined EgtB and OvoA substrate binding pocket flexibility (Scheme 2). EgtB does not accept OvoA’s substrates as its alternative substrates (reactions B and C, Scheme 2). Interestingly, OvoA has much more flexibility in substrate specificity. OvoA can accept γ-Glu-Cys as a substrate and oxidatively couples it with His to form compound 15 (reaction E, Scheme 2). OvoA also can accept hercynine (2) as a substrate (reaction F, Scheme 2). More interestingly, 1H-NMR spectrum of this reaction gives a new signal at 7.12 ppm (reaction F, Figure 1). In comparison with the 1H-NMR spectra of native EgtB reaction (reaction A, Figure 1) and native OvoA reaction (reaction D, Figure 1), the 7.12 ppm signal highly suggests that compound 4 is the product from the OvoA-catalyzed oxidative coupling between Cys and hercynine (Scheme 2, Figure 1C and Figure 11S). Formation of 4 implies a change in OvoA regio-selectivity from the OvoA-type (reaction D, Figure 1) to the EgtB-type (reaction F, Figure 1) upon the change of histidine to hercynine.

Scheme 2.

Examing EgtB- and OvoA-substrate specificities.

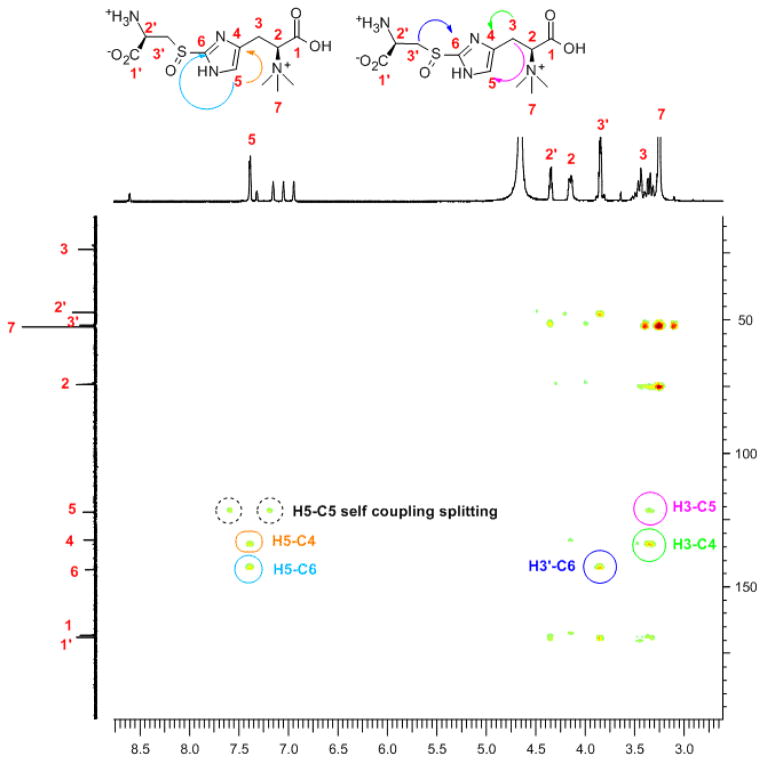

To provide further evidence to support compound 4 structural assignment, it was isolated and characterized by mass spectrometry and several NMR-spectroscopies (1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, and 2D-NMR including COSY, HMBC and HMQC, Figure 2 and Figures 12S-17S). 1H-13C correlations between H-5 and C-4, C-6 in HMBC characterization supports compound 4 structural assignment (Figure 2). Additional cross-peaks (between H-3′ and C-6, and between H-3 and C-4, C-5, Figure 2) are also consistent with the compound 4 structure. HMQC spectrum suggests that the only proton in compound 4 imidazole ring (δ 7.45 ppm) is at histidine δ-carbon (122 ppm, Fig. 16S), which provides additional evidence for an OvoA-catalyzed direct 2 → 4 conversion. In Figure 2 and Fig. 16S spectra, in order to well-resolve the resonances in the 3.0 – 4.5 ppm region, the sample is acidified. As a result, the imidazole ring hydrogen chemical shift (Figure 2) is now at 7.45 ppm instead of 7.12 ppm in Figure 1.

Figure 2. HMBC-NMR analysis.

of compound 4. H-5 shows 1H-13C correlations between C-4 (orange circle) and C-6 (cyan arrow). Additional cross-peaks between H-3′ and C-6 (blue circle), H-3 and C-4 (green circle), C-5 (pink circle) are also shown.

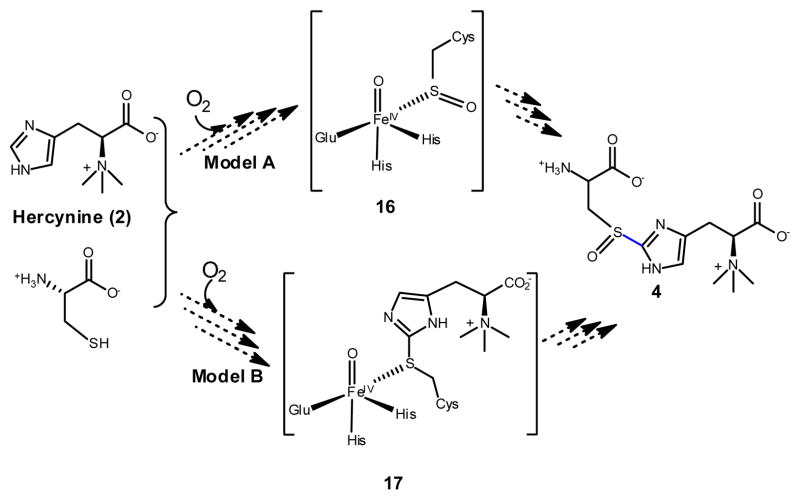

Upon the change of histidine to hercynine, OvoA changes its oxidative C-S bond formation regio-selectivity. This result highly suggests that OvoA binding pocket for histidine amino group plays a key role in determining imidazole ring binding orientation, which in turn determines the oxidative C-S bond formation regio-selectivity. To test this hypothesis, mono- and dimethyl-histidine were synthesized. Indeed, OvoA can also make use of them as alternative substrates. Interestingly, when monomethyl-histidine (9) and cysteine are used as the substrates, OvoA produces two oxidative coupling products, compound 10 and compound 11 in a ratio of 2:3 (Scheme 3 and Figure 19S). In case of dimethyl-histidine (12), compound 13 is the dominant product and compound 14 is barely detectable in our 1H-NMR assay (Scheme 3 and Figure 20S). Results from these studies indicate that OvoA substrate binding pocket for the histidine amino group plays a key role in orientating substrates in the enzyme active site, which in turn determines the oxidative C-S bond formation regio-selectivity (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

New OvoA-chemistries.

In air-saturated HEPES buffer (~ 250 μM of oxygen), these new OvoA reactions were characterized kinetically by monitoring the oxygen consumption rate using the NeoFoxy oxygen electrode. A) When histidine and cysteine are the substrates, kinetic parameters are: kobs of 572 ± 20 min−1 and Km of 420 ± 31 μM for His, Km of 300 ± 34 μM for Cys; B)When Cys and monomethyl histidine (9) are the substrates, the kinetic parameters are: kobs of 527 ± 10 min−1 and a Km of 466 ± 32 μM for monomethyl histidine, a Km of 0.99 ± 0.05 mM for Cys; and C) When Cys and dimethyl histidine (12) are the substrates, the kinetic parameters are: kobs of 367 ± 8 min−1 and a Km of 466 ± 38 μM for hercynine, a Km of 1.61 ± 0.12 mM for Cys; D)When Cys and hercynine (2) are the substrates, the kinetic parameters are: kobs of 270 ± 5 min−1 and a Km of 395 ± 30 μM for hercynine, a Km of 3.19 ± 0.41 mM for Cys.

In summary, our studies here revealed that OvoA has a very relaxed substrate binding pocket and can accept EgtB substrates as alternatives. Moreover, by modulating the histidine amino group methylation state, the regio-selectivity of OvoA-catalysis changes from the OvoA-type to the EgtB-type (Scheme 3). Due to many of the ergothioneine’s beneficial roles to human health,1c, 16 there is a long interest of developing more efficient methods for its production.17 The discovery of this unique OvoA chemistry (a direct 2 → 4 conversion) suggests that such a chemistry may be further explored for future ergothioneine production through metabolic engineering. This transformation not only shortens the ergothioneine biosynthetic pathway by two steps (eliminate EgtA and EgtC steps, please referring to Scheme 1), but also eliminates the competition between ergothioneine and glutathione biosyntheses because γ-Glu-Cys is a substrate in both EgtB reaction and glutathione biosynthesis.

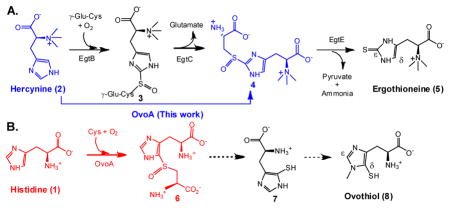

Several mechanistic models were proposed for the oxidative C-S bond formation in EgtB and Ovo-A catalysis since their discovery.15, 18 The oxidative C-S bond formation in OvoA and EgtB seems to be distinct from currently known biological C-S bond formation mechanisms.1a,1c–d,8 Thus far, mechanistic evidence is not yet available for differentiating among the proposed mechanistic options in the literature. Both EgtB and OvoA catalyze four-electron oxidation processes and two different functional groups are constructed in these reactions (sulfoxide and C-S bond, Scheme 4). Thus, the first mechanistic issue to be addressed in OvoA and EgtB catalysis is whether the sulfenic acid formation (model A) or the C-S bond formation (model B) is the first step. This mechanistic question is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Scheme 4.

Two OvoA mechanistic routes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is partially supported by NSF award (CHE–1309148) and NIH award (GM093903) to PL. We thank the NSF (CHE0619339, CHE 0443618) for the 500MHz NMR and the high-resolution mass spectrometer used in this work. We also thank NSF (DBI0959666) for the Perkin Elmer Elan 6100 DRC instrument and Drs. Robyn Hannigan, Alan Christian and Bryanna J. Broadaway (University of Massachusetts Boston) for Fe analyses. We thank Prof. John Snyder for helps on NMR analysis.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedure, characterization data and copies of the 1H- and 13C-NMR of the synthesized compounds 2, 4 and 6. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Fontecave M, Ollagnier-de-Choudens S, Mulliez E. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2149. doi: 10.1021/cr020427j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kessler D. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2006;30:825. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hand CE, Honek JF. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:293. doi: 10.1021/np049685x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fahey RC. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lin C-I, McCarty RM, Liu H-w. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:4377. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35438a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Parry D, Ed Barton RJ, Nakanishi K, Meth-Cohn O. Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry (I) Vol. 1. Pergamon; Oxford: 1999. p. 825. [Google Scholar]; (g) Wang L, Chen S, Xu T, Taghizadeh K, Wishnok J, Zhou X, You D, Deng Z, Dedon P. Nature Chem Biol. 2007;3:709. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Scharf DH, Remme N, Habel A, Chankhamjon P, Scherlach K, Heinekamp T, Hortschansky p, Brakhage AA, Hertweck C. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12322. doi: 10.1021/ja201311d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Wang Q, Song F, Xiao X, Huang P, Monte A, Abdel-Mageed WM, Wang J, Guo H, He W, Xie F, Dai H, Liu M, Chen C, Xu H, Liu M, Piggott AM, Liu X, Capon RJ, Zhang L. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:1231. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willey JM, van der Donk WA. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Booker SJ, Cicchillo RM, Grove TL. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11:543. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Parry RJ. Tetrahedron. 1983;39:1215. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fugate CJ, Jarrett JT. Biochim Biophys Acta-Proteins & Proteomics. 2012;1824:1213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jurgenson CT, Begley TP, Ealick SE. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.072407.102340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Schwarz G, Mendel RR. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Leimkuhler S, Klipp W. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:239. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whittaker JW. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:227. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler D. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2006;30:825. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldwin JE, Bradley M. Chem Rev. 1990;90:1079. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Mueller EG. Nature Chem Biol. 2006;2:185. doi: 10.1038/nchembio779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Johnson DC, Dean DR, Smith AD, Johnson MK. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005:247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Grundemann D, Harlfinger S, Golz S, Geerts A, Lazar A, Berkels R, Jung N, Rubbert A, Schomig E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408624102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Melville DB, Eich S. J Biol Chem. 1956;218:647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Fahey RC, Newton GL, Dorian R, Kosower EM. Anal Biochem. 1981;111:357. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90573-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Genghof DS, Inamine E, Kovalenko V, Melville DB. J Biol Chem. 1956;223:9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Briggs I. J Neurochem. 1972;19:27. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1972.tb01250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Epand RM, Epand RF, Wong SC. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1988;26:623. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1988.26.10.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Hartman PE. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:310. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86124-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanret C. Compt rend. 1909;149:222. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seebeck FP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6632. doi: 10.1021/ja101721e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner E, Klevit R, Hager LJ, Shapiro BM. Biochemistry. 1987;26:4028. doi: 10.1021/bi00387a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braunshausen A, Seebeck FP. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1757. doi: 10.1021/ja109378e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Weaver KH, Rabenstein DL. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1904. [Google Scholar]; (b) Scott EM, Duncan IW, Ekstrand V. J Biol Chem. 1963;238:3928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Xu J, Yadan JC. J Org Chem. 1995;60:6296. [Google Scholar]; (b) Erdelmeier I, Daunay S, Lebel R, Farescour L, Yadan JC. Green Chem. 2012;14:2256. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01870j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Bushnell EA, Fortowshy GB, Gauld JW. Inorg Chem. 2012:13351. doi: 10.1021/ic3021172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mashabela GT, Seebeck FP. Chem Commun. 2013;49:7714. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42594k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.