Abstract

Hsaio and colleagues link gut microbes to autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in a mouse model. They show that ASD symptoms are triggered by compositional and structural shifts of microbes and associated metabolites, but symptoms are relieved by a B. fragilis probiotic. Thus probiotics may provide therapeutic strategies for mental disorders.

Rapid advances in analytical and sequencing technologies have spurred a renaissance of research into connections between the microbial communities that inhabit our gut and physiological conditions. Given the complexity of gut microbial communities, estimated to contain 500–1000 species that considerably expand our metabolic potential beyond what the human genome encodes, it is perhaps unsurprising that they can influence many aspects of our physiology and gut-linked health and disease (Clemente et al., 2012). For example, TLR5 knockout mice can become obese because an altered microbial community, instead of affecting metabolic efficiency, increases its appetite (Vijay-Kumar et al., 2010), or in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis, demyelination only occurs in the context of the gut microbiota (Berer et al., 2011). In addition, microbial impacts on neurology are also evident, including anxiety and sociability in mice (Collins et al., 2013), and changing emotions in humans who received fermented milk with probiotics (Tillisch et al., 2013). Hsaio et al. (2013) make a striking contribution to our understanding of the influence of gut bacteria using an animal model that replicates maternal immune activation risk factor type autism behaviors in mouse offspring. They show that microbial shifts within the gut of a mouse resulted in changes of metabolites in the bloodstream and that these lead to the onset of autism-like behaviors. Moreover, administering a probiotic beneficial bacterium, Bacteroides fragilis, reversed the physiological, neurological and immunological anomalies.

Autism diagnoses have increased rapidly over the last decade (currently 1 in 88 births, versus 1 in 150 reported in 2000; www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html), but no clear relationships between genetic factors and the ASD symptoms have yet been found. However, gastrointestinal ASD symptoms suggest a potential breakdown in normal symbiotic relationships between the host and its microbes (a dysbiosis), which may affect health via systemic as well as direct pathways, including immune system interactions. In ASD cases linked to maternal-viral or -bacterial infection during pregnancy, gut barrier integrity is reduced, increasing permeability. This condition, with maternal immune activation (MIA), can increase the abundance of certain bacterial metabolites in the blood and serum of offspring, which if aberrant could influence host immunology and neurology. Although current literature regarding microbiota associated with ASD patients is limited and contradictory, there is evidence that ASD patients lack certain beneficial bacteria in their gut, e.g. Prevotella (Kang et al., 2013).

To bring these issues into sharper focus in an experimentally tractable system, Hsaio and colleagues used the maternal immune activation (MIA) paradigm to model autism in mice. In this animal model, pregnant mice were injected with an immunostimulant, polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C), which mimics a viral infection. MIA results in offspring with ASD-like behavioral symptoms and neuropathology. They showed that this mouse model for MIA reduced intestinal integrity through altered gut bacterial community. In offspring with reduced gut barrier integrity, the authors identified ~8% of assayed bacterial metabolites that differed significantly in abundance compared to those with intact gut barrier function. When these ASD mice were fed with Bacteroides fragilis, a gut microbe with positive effects on the immune system, the abundance of 34% of these metabolites changed back, gut barrier integrity was improved, the gut-microbiome was restored to a non-ASD state, and ASD-related behavioral abnormalities were ameliorated. In addition, a 46-fold increase of 4-ethylphenylsulfate (4-EPS) in the serum of MIA offspring returned to normal levels.

The authors conclusively demonstrated the gut bacteria generate 4-EPS by showing that germ-free mice have undetectable serum concentrations of 4-EPS. Interestingly, 4-EPS accumulates in patients with chronic renal failure, and is related to p-cresol, which is present in urine of children with ASD and suggested as a human autism biomarker (Persico and Napolioni, 2013), although additional studies would be needed to confirm the generality of this finding. Coincidently, the MIA mice in this study had p-cresol in their serum, but it was not at significant levels. When the authors added synthetic 4-EPS to wild-type mice, they induced anxiety-like behavior similar to that observed in MIA mice. A second metabolite elevated in the MIA serum, and normalized by treatment with B. fragilis, was indolepyruvate. Indolepyruvate is generated by microbial tryptophan catabolism and is related to indolyl-3-acryloylglycine, another human autism marker. Indolepyruvate elevation could be linked to increased serum levels of serotonin, yet another human autism biomarker. Application of the B. fragilis probiotic, increased many other metabolites including N-acetylserine, which the authors hypothesize may provide protection against some ASD symptoms.

This groundbreaking study provides some of the first conclusive evidence of the impact of MIA on GI tract integrity that is reversible via administration of a specific probiotic. It also shows that a suite of metabolic markers is generated by bacteria, altered in dysbiosis, and normalized by probiotic treatment. Importantly, the authors demonstrate that elements of the MIA phenotype can be caused by a specific microbial metabolite. This is an excellent example of how a combination of bacterial community profiling, mouse models, germ-free mice, and metabolomics can be used to mechanistically understand the effects of the gut microbiome on health and disease states, and to develop therapeutic strategies to treat key conditions.

The broader potential of this research is obviously an analogous probiotic that could treat human ASD. The observation that 4-EPS imparts anxiety-like symptoms in normal mice suggests that other mental illnesses may also be linked to microbial metabolites in serum. If probiotics, such as B. fragilis, that ameliorate ‘bad’ metabolites along with their negative neurological consequences could be identified in relevant mouse models, the implications for the mental health of humans is extraordinary. MIA has been linked to a range of human conditions, including depression and schizophrenia (Knight et al., 2007), and several reports indicate that probiotics can treat anxiety and PTSD in mouse models, including one model that requires an intact vagus nerve for gut-brain signaling (Bravo et al., 2011). Therapies that target tour microbial side may hold the key to making progress against a wide range of notoriously difficult psychiatric illnesses.

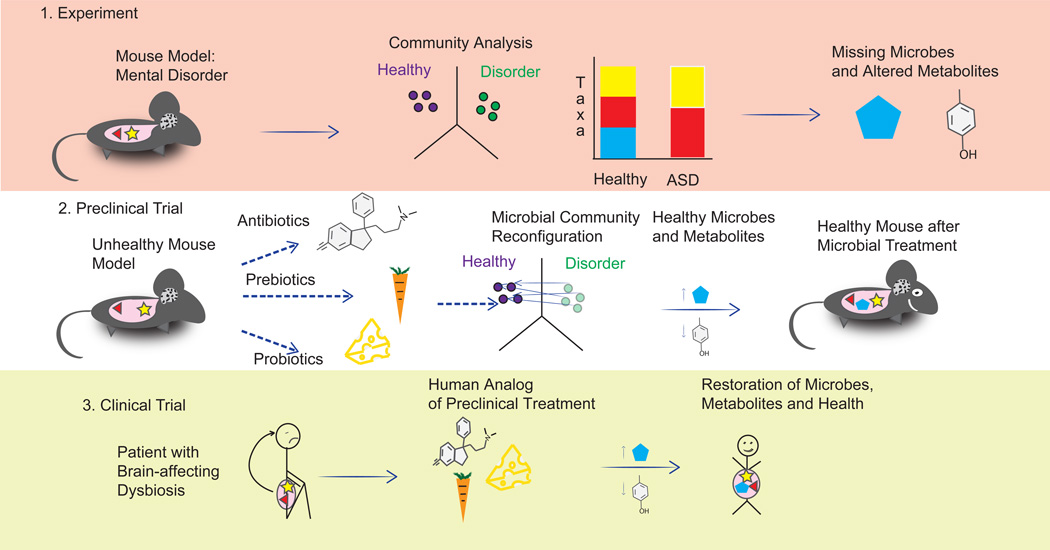

Figure 1.

Evolution of a pipeline for therapeutic strategies for mental disorders based on microbiome and metabolite profiling. Panel 1 (top): Experiments using mouse models with induced mental disorders (for example, an MIA mouse with ASD symptoms) and subsequent community profiling can provide a mechanistic understanding of the importance of specific gut microbes and their metabolites in triggering the illness process, especially when lead compounds or microbes are applied to germ-free mice. Panel 2 (middle): Potential treatments to restore the healthy state of the mouse model (replacements of the identified missing microbes and/or the differences in metabolites they cause) can be tested and validated in preclinical trials, including different strategies for altering the microbial community and/or metabolite profile. For example, introducing a beneficial microbe such as the probiotic strains of B. fragilis used by Hsaio et al. may decrease a harmful metabolite rather than increasing a beneficial one. Panel 3 (bottom): Formulation and application of analogous treatments in human trials may lead to new ways to treat human mental disorders. Careful clinical trials will be needed in humans, as the effects of a given microbe and metabolite may differ in different species.

References

- 1.Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. Cell. 2012;148(6):1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, Cullender TC, Mwangi S, Srinivasan S, Sitaraman SV, Knight R, Ley RE, Gerwitz AT. Science. 2010;328(5975):228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.1179721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berer K, Mues M, Koutrolos M, Rasbi ZA, Boziki M, Johner C, Wekerle H, Krishnamoorthy G. Nature. 2011;479(7374):538–541. doi: 10.1038/nature10554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins SM, Kassam Z, Bercik P. Current Opinions in Microbiology. 2013;16(3):240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L, Jiang Z, Stains J, Ebrat B, Guyonnet D, Legrain-Raspaud S, Trotin B, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1394–1401. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsaio EY, McBride SW, Hsien S, Sharon G, Hyde ER, McCue T, Codelli JA, Chow J, Reisman SE, Petrosino JF, Patterson PH, Mazmanian SK. Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.024. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang DW, Park JG, Ilhan ZE, Wallstrom G, Labaer J, Adams JB, Krajmalnik-Brown R. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e68322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Persico AM, Napolioni V. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2013;36(0):82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight JG, Menkes DB, Highton J, Adams DD. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(5):424–431. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, Escaravage E, Savignac HM, Dinan TG, Bienenstock J, Cryan JF. PNAS. 2011;108(38):16050–16055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]