Abstract

Background and Objective

Severe thermal injury is associated with extreme and prolonged inflammatory and hypermetabolic responses, resulting in significant catabolism that delays recovery or even leads to multiple organ failure and death. Burned patients exhibit many symptoms of stress-induced diabetes, including hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperlipidemia. Recently, the NLRP3 inflammasome has received much attention as the sensor of endogenous “danger signals” and mediator of “sterile inflammation” in type II diabetes. Therefore, we investigated whether the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in the adipose tissue of burned patients, as we hypothesize that, similar to the scenario observed in chronic diabetes, the cytokines produced by the inflammasome mediate insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction.

Subjects

We enrolled 76 patients with burn sizes ranging from 1% to 70% total body surface area (TBSA). Severely burned patients all exhibited burn-induced insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.

Measurements and Main Results

We examined the adipose tissue of control and burned patients and found, via flow cytometry and gene expression studies, increased infiltration of leukocytes - especially macrophages - and evidence of inflammasome priming and activation. Furthermore, we observed increased levels of IL-1β in the plasma of burned patients when compared to controls.

Conclusions

In summary, our study is the first to show activation of the inflammasome in burned humans, and our results provide impetus for further investigation of the role of the inflammasome in burn-induced hypermetabolism and, potentially, developing novel therapies targeting this protein complex for the treatment of stress-induced diabetes.

Keywords: burn, inflammasome, inflammation, hypermetabolism, morbidity, mortality

Introduction

Severe thermal injuries result in a wide array of stress-associated inflammatory and metabolic changes aimed at restoring homeostasis of the body.[1, 2] Unfortunately, when these changes become uncontrolled, persisting far past the initial trauma, they lead to a state of severe metabolic dysfunction.[3] Accordingly, trauma, critically ill, and burned patients often develop a form of stress-induced diabetes (with hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and hyperlipidemia)[4] which is linked to marked increases in morbidity and mortality.[5] Particularly, in burned patients, studies have demonstrated that the significant pathophysiological changes and extreme inflammatory responses are not only present during acute hospitalization, but persist for a prolonged period and lead to severe catabolism, subsequently causing delays in their rehabilitation and reintegration.[6] Although intensive efforts have long focussed on identifying the underlying mechanisms of these extreme metabolic alterations, few studies have manage to elucidate how thermal injury induces hypermetabolism, prolonged inflammation and stress responses, and insulin resistance, and whether these alterations are responsible for the increased morbidity and mortality.

In contrast to our lack of understanding of stress-induced diabetes, the molecular pathology of type II diabetes is better understood. Recently, in addition to the long-established molecular pathways that regulate insulin signalling and downstream effectors, a new modulator of insulin sensitivity was identified. Inflammasomes, protein complexes characterized by their specific Nod-like receptor (NLR) family member (i.e., the portion of the complex responsible for ligand recognition), are now known to be important mediators in the cross talk between inflammation and metabolic regulation[7–13] by serving as a platform for caspase 1 activation, which leads to subsequent proteolytic maturation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18.[14, 15]

As such, in addition to the major function of inflammasomes in detecting pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)[16] and induction of canonical inflammatory responses, the NLRP3 (nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family, pyrin-domain-containing-3) inflammasome was recently indicated in promoting obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance via detection of obesity-associated, endogenous damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs).[17, 18] In obese mice, lack of NLRP3 expression prevents inflammasome activation in response to high fat diet-associated DAMPs and enhances insulin signalling in the fat and liver, both important metabolic tissues.[19] Work by Ting and colleagues suggest that the mechanism of inflammasome activation in diabetes involves detection of saturated fatty acids, potentially resulting from lipotoxicity in the adipose tissue of obese mice.[20] Others have suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequent increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS) may be responsible for priming and activating the inflammasome[21, 22] in metabolic disorders. Regardless of the method of activation, in terms of type II diabetes and insulin resistance, generation and release of IL-1β by the inflammasome interferes with insulin sensitivity via both direct (stimulation of the IL-1 receptor and downregulation of IRS1)[23] and indirect mechanisms.[20] When viewing all of this evidence together, it becomes clear that inflammation and insulin resistance are tightly linked via the NLRP3 inflammasome.

In the current study, we hypothesized that the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in the white adipose tissue of burned patients, resulting in concomitant elevation of serum IL-1β, and that this may be one mechanism of insulin resistance/metabolic alterations in patients with thermal injuries and stress-induced diabetes. We therefore designed a study to examine the subcutaneous fat of burned and non-burned patients for relevant parameters such as leukocyte infiltration, expression of macrophage markers, and elevated inflammasome activity.

Methods and Materials

Patients

Patients that were admitted to our burn centre with thermal injuries, required surgery, and were eligible for enrollment were consented for blood and tissue collection. These procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (Study #194-2010). All patients received standard of care according to our clinical protocols, including early excision and grafting, early nutrition, adequate ventilation, adequate antibiotic coverage, etc. All patients studied suffered hyperglycemia and required insulin treatment during their stay in the burn unit. Insulin dosage was titrated on a sliding scale pursuant to the patient’s blood glucose levels and corresponding needs.

For analyses conducted in this study, patients are classified as burned/non-burned, or as acute minor burns (burns that covered a total body surface area [TBSA] of ≤30%), acute major burns (TBSA of ≥30%), and controls (patients suffering a thermal injury >3 years ago, admitted into our burn centre for wound management, or for reconstructive surgeries unrelated to burns). Excised fat was removed until the level of healthy tissue. However, the skin containing the upper layer of the adipose tissue that was injured, was not included in this examination. This was healthy looking fat in the intermediate zone that should not have been affected by the thermal injury directly. Hence, there is activation in this adipose tissue that is not due to the burn itself because this area was directly affected. Upon excision, all adipose tissue samples were immediately prepared for flow cytometry staining. The amount of patients for each of the measured variables differed due to the laborious flow analysis procedure which takes 2–3 days and requiring a large amount of adipose tissue which was not available in every patient. However, the majority the skin-fed blood and muscle, which varies in quantity, was able to be collected. Moreover, obese patients (BMI>30) or those having a known medical history of diabetes mellitus were excluded, as these patients would be expected to exhibit leukocyte infiltration and inflammasome activation in the adipose tissue, independent of burn injury.

Harvesting of Stromal Vascular Fractions from White Adipose Tissue

Collected specimens were immediately transferred to the laboratory, where they were digested with collagenase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 1 mg/ml in RPMI1640 in a shaking incubator for 2 hours at 37°C. The digest was then strained through sterile gauze to remove particulates, and the cell fraction was collected by centrifugation. The cell pellets were washed multiple times with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), resuspended in HBSS, and red blood cells were removed by density centrifugation with Lympholyte H (Cedarlane, Burlington, ON), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cell suspension was then passed through a 100 micron strainer (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, ON), and cells were counted.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

The percentage of leukocytes, monocytes, and T lymphocytes in the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) was determined by conducting flow cytometric analysis of cell surface markers. The following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies were used: anti-CD45 (FITC, BD Biosciences, Mississauga, ON), anti-CD14 (PE, eBiosciences, San Diego, CA), anti-CD3 (APC, BD Biosciences, Mississauga, ON). Activity of caspase 1 was determined using the Green FLICA Caspase I Assay Kit (ImmunoChemistry Technologies, Bloomington, MN), following the manufacturer’s flow cytometry protocol.

Gene expression studies

Total RNA was harvested from fresh or snap-frozen adipose tissue using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). After the yield and quality of RNA were determined via Nanodrop, RT-PCR was conducted (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and the cDNA was used in real-time gene expression studies (ABI/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The sequences of the primers for each target gene are listed below. Expression of 18s rRNA was used as a “loading” control for each sample. Gene expression levels were determined using the following formula: 2^(−ΔCt)

Primer sequences:

EMR-1; F-GATGAAGATCGGGTGTTCCACAA, R-CCATGCCCACAAAGGAGACAA

CD11b; F-AGATTGTGTTTTGAGGTTTC, R-TGTGTATGTGTGGTGTGTGT

NLRP3; F-TGAAGAAAGATTACCGTAAG, R-GCGTTTGTTGAGGCTCACACT

IL-1β; F-ATGATGGCTTATTACAGTGG, R-AGAGGTCCAGGTCCTGGAA

18s; F-GGCCCTGTAATTGGAATGAGTC, R-CCAAGATCCAACTACGAGCTT

Circulating IL-1β levels

The cytokine profile in the plasma of patients was analysed using the Luminex Multiplex system with the Milliplex (Millipore, Billerica, MA) human cytokine/chemokine 39-plex (cat. HCYTOMAG-60K-PX39), following the manufacturer’s protocol. However, for the purposes of this study, only the level of IL-1β (Fig. 5), TNF alpha, IL-6, and IL-8 (Supp. Fig. 1) are presented.

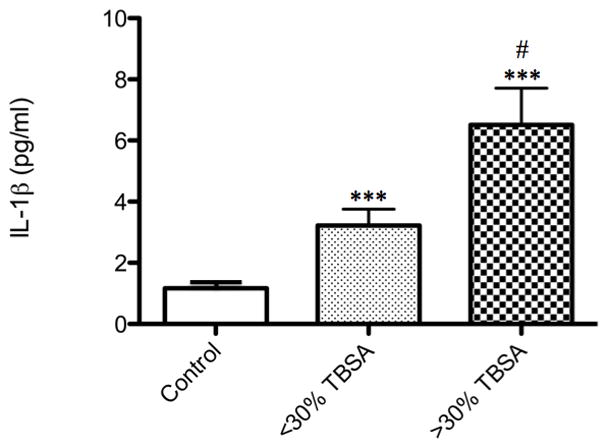

Figure 5. Elevated circulating protein levels of IL-1β, post-burn.

Patients with acute minor burns (≤ 30% TBSA, n=42) and acute major burns (≥ 30% TBSA, n=34) exhibit significantly elevated levels of plasma IL-1β (***p<0.0001) when compared to controls (n=5), as measured by luminex technology. Comparing severity of burn injury, the large burn group demonstrated increased IL-1β (#p<0.05). All data is presented as mean values with error bars as SEM.

Statistical analysis

Student’s unpaired t-test was used to compare all results, with Welch’s correction where appropriate. Data is presented as means and standard error of the mean (SEM) for continuous variables, frequency and percentages for categorical variables. Statistical analysis was conducted using Wilcoxon rank sum test and student’s t-test where appropriate. Statistical comparisons were conducted using SPSS 20 and figures were generated using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. Significance was accepted at a p value less than 0.05.

Results

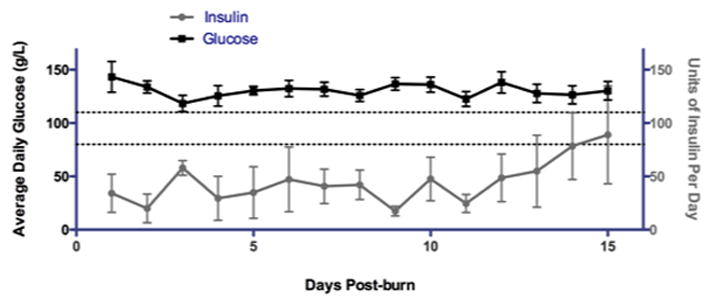

Including 64 burns and 12 controls, a total of 76 patients were enrolled in this study. Demographics and outcomes are presented in Table 1. The average age of our patients was between 40 (control) and 50 (burn) years, average length of stay was 34 days, and average TBSA was 25%. Of the 64 burned patients, 56 survived and were released from the burn unit, while 8 of the patients expired during their stay. All burned patients demonstrated some degree of insulin resistance, associated with hyperglycemia (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Burned Patients | Control Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 64 | 12 |

| Age (years) | 51 ± 18 | 40 ± 13 |

| Sex, Female/Male | 21/43 | 8/4 |

| Length of Stay (days) | 34 ± 28 | |

| TBSA (%) | 25 ± 18 | |

| Mortality, Survivors/Nonsurvivors |

Figure 1. Hyperglycemia, hyperinsulenimia, and insulin resistance in burned patients.

(Black line) Average daily glucose is shown for a portion of the patients included in this study. Burned patients exhibit sustained hyperglycemia following thermal injury. Dashed lines represent normal glucose range. (Grey line) Average exogenous insulin units administered during the course of standard burn care per day is shown for a portion of the patients included in this study.

Infiltration of Leukocytes in White Adipose Tissue, Post-burn Injury

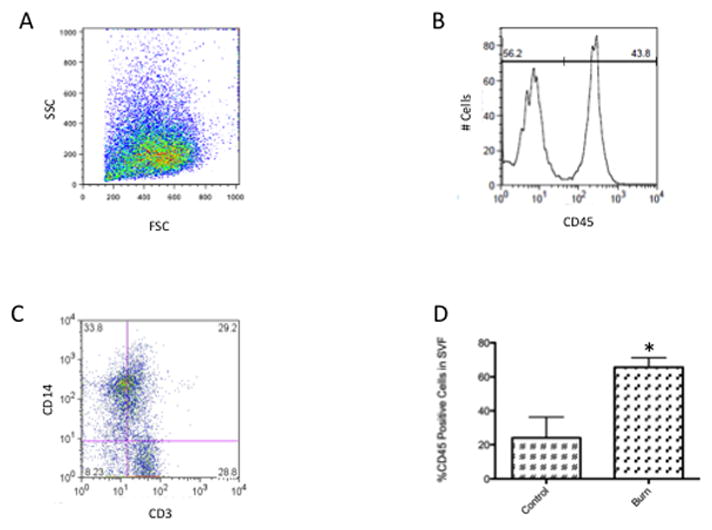

We first investigated whether there are increased numbers of leukocytes, particularly macrophages, in the white adipose tissue of burned patients. Subcutaneous adipose tissue was collected from patients that required surgery to excise thermally injured tissue. Following processing, the SVF was harvested and labelled with anti-CD45, a common leukocyte marker (Fig. 2b). To further characterize the CD45+ population, we studied the fraction of CD14+ (monocytes/macrophages) and CD3+ (T lymphocytes) cells in the SVF. Though we saw elevated levels of CD14 and CD3+ cells in the SVF of burned patients, without fail (data not shown), the observed levels of CD14+ cells and T cells in patients, post-burn, varied greatly (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2. Increased leukocyte infiltrates in white adipose tissue of patients with acute burn injuries.

(A) A representative forward and side scatter profile of flow cytometric analysis of the stromal vascular fraction isolated from human white adipose tissue. (B) A histogram analysis to measure the percentage of CD45+ cells within the SVF. (C) A representative profile of CD14 and CD3 surface expression within the CD45+ population of the SVF. (D) Mean and SEM for the percentage of CD45+ cells in the SVF isolated from control (n=3) or burned patients (n=28). *p<0.05 vs. control.

Using flow cytometry, we found that the percentage of CD45+ cells within the isolated SVF was elevated more than 3-fold in patients suffering from acute thermal injury when compared to reconstructive surgical patients, (p=0.009, Fig. 2d).

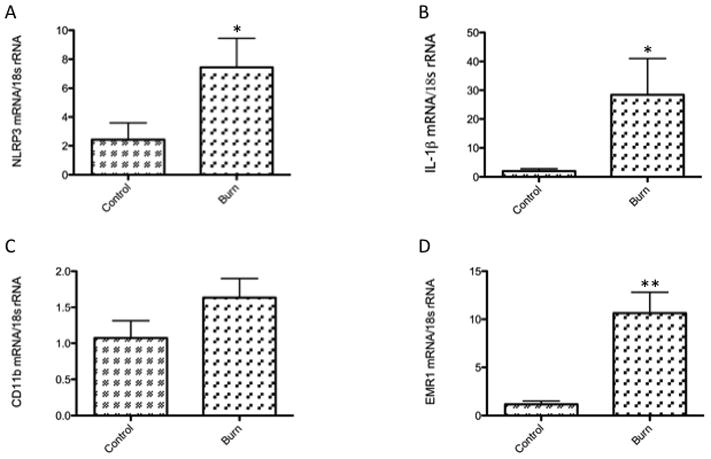

Myeloid Markers and NLRP3 inflammasome-associated Transcripts are Increased in Adipose Tissue, Post-burn

In order to corroborate our flow cytometry findings, we then studied the transcript levels of various myeloid and macrophage markers in adipose tissue, post-burn. Real-time gene expression studies of myeloid marker CD11b and macrophage marker EMR-1 indicated that there are increased levels of these transcripts in patients with severe acute burns when compared to controls (Fig. 3c and d), EMR-1 significantly so (~10-fold, p<0.01). Furthermore, analysis of genes indicating NLRP3 inflammasome priming, namely NLRP-3 and IL-1β, revealed a significant increase (~4-fold and 15-fold, respectively, p<0.05 for both) in transcript levels in the adipose tissue of burned patients (Fig. 3a and b).

Figure 3. Elevated expression of inflammasome priming and myeloid/macrophage markers in white adipose tissue, post-burn.

(A) and (B) illustrate gene expression of inflammasome priming markers. Steady-state transcript levels for both NLRP3 (control, n=6 and burn, n=25) and IL-1β (control, n=10 and burn, n=34) are significantly increased in burned patients. (C) Expression of CD11b (control, n=3 and burn, n=9), a myeloid and activated lymphocyte marker was not significantly increased in burned patients, but (D) levels of EMR1 mRNA (control, n=3 and burn, n=9), a specific macrophage marker, were significantly higher in the WAT tissue of the burn group when compared with controls. All data is presented as mean values with error bars as SEM, *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

Caspase-1 is activated in CD14+ leukocytes of the SVF, post-burn

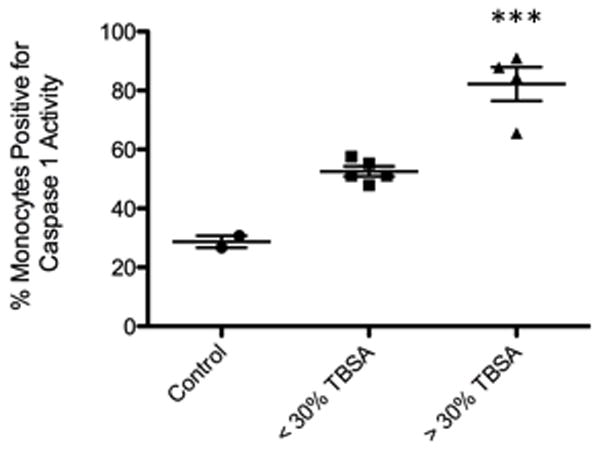

Next, we sought to determine if the cells of the SVF demonstrated evidence of, not only inflammasome priming, but also inflammasome activity. Assembly and activation of the NLRP3-inflammasome ultimately leads to caspase-1 activity (the “active” portion of the protein complex). Caspase 1 then processes pro- IL-1β into the mature form. Mature IL-1β can then act upon metabolic tissues, subsequently leading to altered insulin signalling and insulin resistance. To investigate the activity of caspase 1 in the CD14+ cells of the SVF, post-burn, we utilized the flow cytometry-based FLICA assay. Our results showed that patients with a burn size of less than or equal to 30% TBSA exhibited increased caspase 1 activity in the CD14+ fraction relative to controls. The same population of cells derived from patients suffering a burn greater than 30% TBSA demonstrated even greater activity (nearly double) when compared to smaller burns (p<0.0001) or controls (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Inflammasome activity is increased in the CD14+ portion of the stromal vascular fraction in white adipose tissue, post-burn.

(A) Percentage of monocytes staining positive for inflammasome activity in the SVF isolated from WAT of control (n=2), acute minor burns (n=5), and acute major burns (n=4) patients. Results were first gated to exclude CD14- cells, then analyzed for FLICA+ staining in order to ascertain caspase I activity (refer to methods). Inflammasome activity was significantly greater in monocytes of the large burn group (***p<0.001) when compared to the small burn group. Control patients were unburned and donated subcutaneous fat tissue after undergoing liposuction or other surgical procedures for reconstructive purposes. All data is presented as mean values with error bars as SEM.

Circulating levels of IL-1β are increased, post-burn

Assuming that increased NLRP3 inflammasome activity should lead to higher serum levels of IL-1β, we next investigated circulating levels of cytokines in patients following acute burn injuries. Indeed, we found that serum IL-1β was increased for minor burns (approximately 4-fold, p=0.004) and in the major burn group (approximately 6-fold, p<0.0001) when compared with controls (Fig. 5). In addition, the increased IL-1β in the major burn group was significantly greater (p=0.005) relative to minor burns (Fig 5). Furthermore, several other inflammatory cytokines known to be involved in metabolic regulation were elevated in the burned group, as expected and demonstrated in previous publications from our laboratory (Supp. Fig. 1). Despite the greater proportion of males with burn injuries, there were no significant sex differences between the groups for cytokine expression and inflammasome activity (data not shown).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of increased inflammasome activity in the adipose tissue of burned patients. Burned patients not only endure catastrophic surface wounds, but also body-wide deleterious effects resulting from metabolic perturbations such as hyperlipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperglycemia, collectively refered to as “hypermetabolism”.[24] Specifically, metabolic dysfunction in burned patients is more severe than that seen in any other trauma demographic and has been linked to increased incidence of several poor outcomes, including infections, sepsis, delayed wound healing, mutli-organ failure, and most importantly mortality.[25–28] Discovering the mechanisms that lead to post-burn hypermetabolism is of the utmost importance, as little progress has been made in the effort to improve outcomes over the past several decades, and a dearth of novel therapies remains. Thus, the significance of the present study lies in the translational nature – by analyzing samples derived from burned patients, our results provide direct impetus for targeting burn-induced inflammasome activity, ultimately making the goal of novel therapies more attainable.

Our initial efforts to investigate activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the subcutaneous fat of our burned patients stemmed from both 1) our observation that burned patients suffer extreme inflammatory responses (even in the absence of complicating infections)[3, 29] and 2) the attention this protein complex is receiving in the type II diabetes literature (mainly regarding macrophages and their contribution to “sterile” inflammation and adipose tissue dysfunction), as our patients suffer similar symptoms, though stress-induced diabetes is of a more acute nature. We began by establishing that there is a 3-fold increase in leukocyte levels in the adipose tissue harvested from our patients (Fig. 2d), indicating increased infiltration and inflammation, as expected. According to work published by Koenen, in the context of adipose tissue and metabolic syndrome, the majority of these leukocytes should be granulocytes, monocytes/macrophages, and T cells.[30] Our flow cytometry findings confirm the presence of monocytes and T cells (Fig. 2c), which we have found to be consistently higher in the burned group (data not shown). However, the levels of monocytes/macrophages and T cells seem to vary greatly with time – and perhaps other factors – and the significance of this finding is currently under investigation.

In most cell types, activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome is controlled by a two-step process: priming followed by activation. Priming involves increased transcription of the components of the complex, such as the receptor, NLRP3, and its target, pro-IL-1β. The second step, activation, occurs when the NLRP3 receptor recognizes one of its many potential ligands and serves as a nucleator for the complex, attracting the adaptor protein ASC, and ultimately caspase I. The result is a protein complex capable of cleaving pro-IL-1β into mature, active IL-1β,[31] which can then be secreted and have a myriad of local and systemic effects, namely impacting insulin sensitivity, both locally and by travelling to other insulin-sensitive tissues, where IL-1 receptor signalling can directly interfere with insulin signalling.[20, 23] It is important to note, as well, that findings so far have not indicated robust expression of NLRP3 in the adipocytes, themselves, indicating that it is most likely the inflammatory and/or stromal cells of the adipose tissue that are initiating and mediating these events.[30]

As such, we went on to corroborate our flow cytometry findings with gene expression studies. Figure 3a and b show a significant increase in NLRP3 and IL-1β transcripts, indicating greater priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the burned group. EMR1 levels were also significantly increased in the RNA isolated from adipose tissue of burned patients (Fig. 3d), indicating an increased presence of macrophages, the most-studied leukocyte with regard to adipose inflammation and metabolic disorders. The CD11b transcript level was not significantly increased (Fig. 3c), but we did not find this data particularly discomfiting, as CD11b is not a marker specific to macrophages and monocytes; it can also be found on granulocytes, neutrophils, and activated T cells. Furthermore, the “control” patients also underwent surgical procedures, which we would expect to cause some local inflammatory responses. Therefore, we had no reason to necessarily expect the expression to be significantly higher in the burn group.

However, the key question posed in this study was: is there greater activation of the inflammasome in the adipose tissue of burned patients? If so, is this activity greater with increasing burn size? If inflammasome activity could be contributing to metabolic dysfunction in burn and, hence, poor outcomes, we would expect to see the results obtained in Figure 4, where activity was significantly increased in the larger burn group compared to the smaller burn group. We were also surprised to find that, though detectable, inflammasome activity in the control samples was half that observed in the small burn group; liposuction and other surgical procedures involve extensive local tissue destruction, which should generate many DAMPs. Importantly, the observation that inflammasome activation was present, but not as great, in the control group gave us greater confidence that our data is not simply the artificial result of the surgical procedure preceding processing of the tissues.

Furthermore, the data presented in Figure 5 illustrates that the observed increase in inflammasome activity results in the expected significant elevation of plasma IL-1β for both acute minor and major burns. As previously mentioned, (adipose-derived) increased circulating levels of IL-1β are now thought to be strongly associated with diabetes and insulin resistance in the context of metabolic syndrome. We believe the same sort of mechanism could be playing a role in the metabolic perturbations observed in our burned patients. Furthermore, we are currently investigating whether the IL-1β levels are most significantly increased in the fat tissue, itself, as it’s very possible that the paracrine inflammatory and metabolic effects of this cytokine are much greater than the endocrine.

Metabolic regulation is an extremely complicated “symphony” of integrated hormonal and nutritional cues, and, we are therefore currently investigating several other kinds of metabolic tissue as well. However, our focus on the adipose tissue in the current study stems from the concept of the “primacy of fat”. According to Osburn and Olefsky, who elegantly reviewed the current state of knowledge regarding inflammation and metabolic disorders recently,[32] tissue-specific knockout studies have shown that restoring metabolic homeostasis in the fat tissue leads to improved metabolic function in other tissues, namely the liver and muscle. Conversely, the opposite relationships do not hold true, indicating that adipose is more important in the “hierarchy” of communication and cross-regulation between these metabolic tissues.

Currently, we do not know which DAMPs might be activating the inflammasome in the adipose tissue of our burned patients, but there are several events that could be occurring, either alone or concomitantly, leading to assembly and activation of this complex. For example, uric acid,[33–35] high concentrations of glucose,[36–39] mitochondrial dysfunction leading to increased reactive oxygen species,[22, 40] and increased lipids[17, 20] (burn patients suffer extensive lipolysis, despite hyperinsulinemia) are all scenarios that have both been observed in burn patients and are known activators of the inflammasome. It is also likely that many of our burned patients experience a “highly primed” inflammasome state,[41] as opportunistic infection (and hence bacterial-derived PAMPs, well-known inflammasome primers) is a common problem in burns. Current and future studies will focus on identifying the PAMPs and DAMPs associated with burn and inflammasome activation in our patients and animal models and whether genetic or pharmacological inhibition of inflammasomes improves post-burn outcomes.

We should mention a few cautionary notes with respect to our study. For instance, the authors believe that the abdominal adipose tissue is probably different from peripheral because the amount is also different. By using adipose tissue that is always excised from the burn wound, it is a medium between the skin that is burned and the superficial adipose that appears unhealthy. Again, this is healthy viable adipose tissue. However it is close to the burn site. Hence, we cannot assume that leukocyte infiltration is uniform within the affected burn tissue and adjacent regions. In addition, there are several types of inflammasomes that lead to caspase 1 activity and generation of IL-1β. Similarly, there are other inflammatory cytokines with established roles in metabolic regulation and insulin resistance (Supp. Fig. 1). We cannot, therefore, conclude that the NLRP3 inflammasome is the only complex, or that IL-1β is the only cytokine, responsible for the results observed. Furthermore, we have focused on macrophages and monocytes in this report, but many other publications have shown that other types of leukocytes play a role in chronic adipose inflammation with regard to metabolic dysfunction, and future studies will take this into account and be more inclusive. It would also be interesting to investigate the phenotype of the macrophages we are studying here, as there is much evidence that polarization of macrophages is key, with some subtypes being beneficial and some being detrimental in metabolic regulation.[32] Finally, most of the literature pertaining to fat and inflammation focuses on the deleterious effects of visceral adipose tissue, and we are assessing subcutaneous fat in our studies. There are several reasons for this, mainly the ease of accessibility (this fat tissue is removed during debridement, regardless of our studies) and our belief that subcutaneous fat is perhaps of equal or greater importance in the specific context of burns.[42]

In summary, we have found increased leukocyte infiltration in the subcutaneous fat tissue of burned patients. At least a portion of these infiltrating leukocytes are of the monocyte lineage, a cell type that is well-characterized in the context of metabolic dysfunction. These monocytes demonstrate increased inflammasome activity that is associated with greater levels of circulating IL-1β. Our data is in agreement with many studies already published in the metabolism literature and indicate a potentially significant role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in the hypermetabolic state that contributes so greatly to poor outcomes in our patient population. Future studies will continue to strengthen the relationship between the NLRP3 inflammasome and stress-induced diabetes and delineate mechanistic details with the goal of developing novel therapies and improving outcomes for burned patients.

Supplementary Material

Burned patients (n=31) exhibit significantly elevated levels of plasma (A) TNFα, (B) IL-6, and (C) IL-8 (*p<0.05, ***p<0.001) when compared to controls (n=2), as measured by luminex technology. Each of these pro-inflammatory cytokines has been shown to contribute to both the acute phase response and insulin resistance in various settings. All data is presented as mean values with error bars as SEM.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This study was supported by -Canadian Institutes of Health Research # 123336.

CFI Leader’s Opportunity Fund: Project # 25407

NIH RO1 GM087285-01

Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation - Health Research Grant Program

Footnotes

Copyright Form Disclosures: Drs. Stanojcic, Chen, Wang, Antonyshyn, and Zuniga-Pflucker received support for article research from NIH and CIHR. Their institutions received grant support from NIH and CIHR. Dr. Jeschke’s institution received grant support from NIH, CIHR, and PSI.

References

- 1.Xiao W, Mindrinos MN, Seok J, Cuschieri J, Cuenca AG, Gao H, Hayden DL, Hennessy L, Moore EE, Minei JP, et al. A genomic storm in critically injured humans. J Exp Med. 2011;208(13):2581–2590. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams FN, Herndon DN, Jeschke MG. The hypermetabolic response to burn injury and interventions to modify this response. Clin Plast Surg. 2009;36(4):583–596. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeschke MG, Gauglitz GG, Kulp GA, Finnerty CC, Williams FN, Kraft R, Suman OE, Mlcak RP, Herndon DN. Long-term persistance of the pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeschke MG, Boehning D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and insulin resistance post-trauma: similarities to type 2 diabetes. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(3):437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeschke MG, Mlcak RP, Finnerty CC, Norbury WB, Gauglitz GG, Kulp GA, Herndon DN. Burn size determines the inflammatory and hypermetabolic response. Crit Care. 2007;11(4):R90. doi: 10.1186/cc6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gauglitz GG, Herndon DN, Kulp GA, Meyer WJ, 3rd, Jeschke MG. Abnormal insulin sensitivity persists up to three years in pediatric patients post-burn. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(5):1656–1664. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wen H, Ting JP, O’Neill LA. A role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in metabolic diseases--did Warburg miss inflammation? Nat Immunol. 2012;13(4):352–357. doi: 10.1038/ni.2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stienstra R, Tack CJ, Kanneganti TD, Joosten LA, Netea MG. The inflammasome puts obesity in the danger zone. Cell Metab. 2012;15(1):10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamkanfi M, Walle LV, Kanneganti TD. Deregulated inflammasome signaling in disease. Immunol Rev. 2011;243(1):163–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lukens JR, Dixit VD, Kanneganti TD. Inflammasome activation in obesity-related inflammatory diseases and autoimmunity. Discov Med. 2011;12(62):65–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menu P, Vince JE. The NLRP3 inflammasome in health and disease: the good, the bad and the ugly. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;166(1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Nardo D, Latz E. NLRP3 inflammasomes link inflammation and metabolic disease. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(8):373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori MA, Bezy O, Kahn CR. Metabolic syndrome: is Nlrp3 inflammasome a trigger or a target of insulin resistance? Circ Res. 2011;108(10):1160–1162. doi: 10.1161/RES.0b013e318220b57b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140(6):821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin C, Flavell RA. Molecular mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30(5):628–631. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdul-Sater AA, Said-Sadier N, Ojcius DM, Yilmaz O, Kelly KA. Inflammasomes bridge signaling between pathogen identification and the immune response. Drugs Today (Barc) 2009;45 (Suppl B):105–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandanmagsar B, Youm YH, Ravussin A, Galgani JE, Stadler K, Mynatt RL, Ravussin E, Stephens JM, Dixit VD. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2011;17(2):179–188. doi: 10.1038/nm.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroder K, Zhou R, Tschopp J. The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor for metabolic danger? Science. 2010;327(5963):296–300. doi: 10.1126/science.1184003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stienstra R, van Diepen JA, Tack CJ, Zaki MH, van de Veerdonk FL, Perera D, Neale GA, Hooiveld GJ, Hijmans A, Vroegrijk I, et al. Inflammasome is a central player in the induction of obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(37):15324–15329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100255108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, Jha S, Zhang L, Huang MT, Brickey WJ, Ting JP. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(5):408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorbara MT, Girardin SE. Mitochondrial ROS fuel the inflammasome. Cell Res. 2011;21(4):558–560. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2011;469(7329):221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jager J, Gremeaux T, Cormont M, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF. Interleukin-1beta-induced insulin resistance in adipocytes through down-regulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 expression. Endocrinology. 2007;148(1):241–251. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeschke MG, Chinkes DL, Finnerty CC, Kulp G, Suman OE, Norbury WB, Branski LK, Gauglitz GG, Mlcak RP, Herndon DN. Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Annals of surgery. 2008;248(3):387–401. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181856241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gore DC, Chinkes D, Heggers J, Herndon DN, Wolf SE, Desai M. Association of hyperglycemia with increased mortality after severe burn injury. J Trauma. 2001;51(3):540–544. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200109000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gore DC, Chinkes DL, Hart DW, Wolf SE, Herndon DN, Sanford AP. Hyperglycemia exacerbates muscle protein catabolism in burn-injured patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(11):2438–2442. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200211000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemmila MR, Taddonio MA, Arbabi S, Maggio PM, Wahl WL. Intensive insulin therapy is associated with reduced infectious complications in burn patients. Surgery. 2008;144(4):629–635. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.07.001. discussion 635–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeschke MG, Kulp GA, Kraft R, Finnerty CC, Mlcak R, Lee JO, Herndon DN. Intensive insulin therapy in severely burned pediatric patients: a prospective randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(3):351–359. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0190OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeschke MG, Barrow RE, Herndon DN. Extended hypermetabolic response of the liver in severely burned pediatric patients. Arch Surg. 2004;139(6):641–647. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.6.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koenen TB, Stienstra R, van Tits LJ, Joosten LA, van Velzen JF, Hijmans A, Pol JA, van der Vliet JA, Netea MG, Tack CJ, et al. The inflammasome and caspase-1 activation: a new mechanism underlying increased inflammatory activity in human visceral adipose tissue. Endocrinology. 2011;152(10):3769–3778. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gross O, Thomas CJ, Guarda G, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: an integrated view. Immunol Rev. 2011;243(1):136–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osborn O, Olefsky JM. The cellular and signaling networks linking the immune system and metabolism in disease. Nat Med. 2012;18(3):363–374. doi: 10.1038/nm.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghaemi-Oskouie F, Shi Y. The role of uric acid as an endogenous danger signal in immunity and inflammation. Current rheumatology reports. 2011;13(2):160–166. doi: 10.1007/s11926-011-0162-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu XR, Zheng XF, Ji SZ, Lv YH, Zheng DY, Xia ZF, Zhang WD. Metabolomic analysis of thermally injured and/or septic rats. Burns: journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2010;36(7):992–998. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamazaki T, Yamazaki T, Ueda T. Secondary hyperuricemia in burn and trauma. Nihon rinsho Japanese journal of clinical medicine. 2003;61 (Suppl 1):313–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shanmugam N, Reddy MA, Guha M, Natarajan R. High glucose-induced expression of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine genes in monocytic cells. Diabetes. 2003;52(5):1256–1264. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dasu MR, Devaraj S, Jialal I. High glucose induces IL-1beta expression in human monocytes: mechanistic insights. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2007;293(1):E337–346. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00718.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vincent JA, Mohr S. Inhibition of caspase-1/interleukin-1beta signaling prevents degeneration of retinal capillaries in diabetes and galactosemia. Diabetes. 2007;56(1):224–230. doi: 10.2337/db06-0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(2):136–140. doi: 10.1038/ni.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tschopp J. Mitochondria: Sovereign of inflammation? European journal of immunology. 2011;41(5):1196–1202. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo M, Yuan SY, Sun C, Frederich BJ, Shen Q, McLean DL, Wu MH. Role of Non-Muscle Myosin Light Chain Kinase in Neutrophil-Mediated Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction During Thermal Injury. Shock. 2012 doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318268c731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cree MG, Wolfe RR. Postburn trauma insulin resistance and fat metabolism. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;294(1):E1–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00562.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Burned patients (n=31) exhibit significantly elevated levels of plasma (A) TNFα, (B) IL-6, and (C) IL-8 (*p<0.05, ***p<0.001) when compared to controls (n=2), as measured by luminex technology. Each of these pro-inflammatory cytokines has been shown to contribute to both the acute phase response and insulin resistance in various settings. All data is presented as mean values with error bars as SEM.