Abstract

Filariasis is traditionally diagnosed following screening of peripheral smear for microfilaria. Clinically lymphatic filariasis mimics the common local diseases. Thus, it is plausible to observe this parasitic infection in histological sections. We encountered three such cases, which displayed diverse patterns of immune response. Presence of both dead and viable worm at the same foci suggests that such immune response could be the result of parasitic death. Histological features such as endothelial injury and granulomatous response attests to the role of Wolbachia bacteria in influencing tissue response.

KEY WORDS: Immune response, lymphatic filariasis, Wolbachia

INTRODUCTION

World Health Organization estimates that more than 120 million people are infected with filaria.[1] With more than 80 countries profiled as “endemic,” filariasis is now the most widely distributed parasite.[2] Lymphatic filariasis is caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi and Brugia timori.[3] Life cycle of the parasite is complex and includes an infective larval stage carried by mosquitoes and adult worm residing in lymphatics of humans, which release microfilaria. These microfilariae are then taken up by the mosquitoes during the blood meal. Microfilariae develop into infective larvae within the mosquitoes. Traditionally, examination of peripheral smear for microfilaria is employed for screening and diagnosis.[4] We encountered three cases of lymphatic filariasis in our Histopathology Department. While many case reports are readily available on the net, very few reviews discussing histological features and pathogenesis were accessible. We present our cases and attempt to construct pathogenetic pathway of the histological features.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 35-year-old male presented with the history of swelling in his right scrotum of 3 month duration, which had become painful from 20 days. Patient was febrile and had no history of trauma. Examination of genitalia revealed a tender, right sided scrotal swelling of variable consistency with negative transillumination and cough impulse. Testis was palpable separately. Ultrasonography revealed 5 × 3.5 cm heterogeneous mass superior to right testis extending into the inguinal canal. Complete hemogram showed neutrophilic leucocytosis, but no eosinophilia or microfilaria. A sonographic presumptive diagnosis of pyohydrocele was considered. Patient underwent incision and drainage following which 50 ml of frank pus was drained. Pus culture failed to show any growth on aerobic incubation. Patient consented for epididymorchidectomy after 6 days. An enlarged epididymis was noted intraoperatively. High inguinal orchidectomy was performed as the operative findings were deemed suspicious for malignancy. Grossly, the specimen sent for pathological examination showed an ill-circumscribed firm mass with areas of hemorrhage in paratesticular region [Figure 1a]. Many dead and degenerated microfilaria were seen microscopically within peritesticular tissue [Figure 2b]. Fibrinopurulent immune response was noted surrounding the worms [Figure 3a].

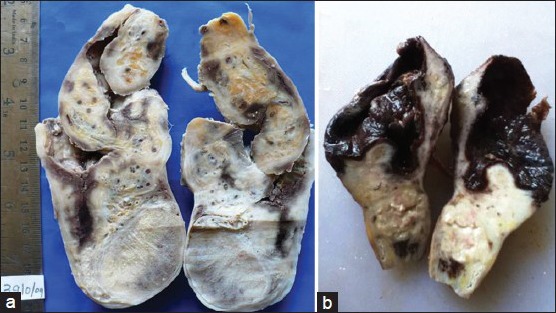

Figure 1.

Gross pathology. (a) Firm ill-circumscribed mass in paratesticular region. (b) Paratesticular ruptured cyst with dark friable material impregnating inner surface

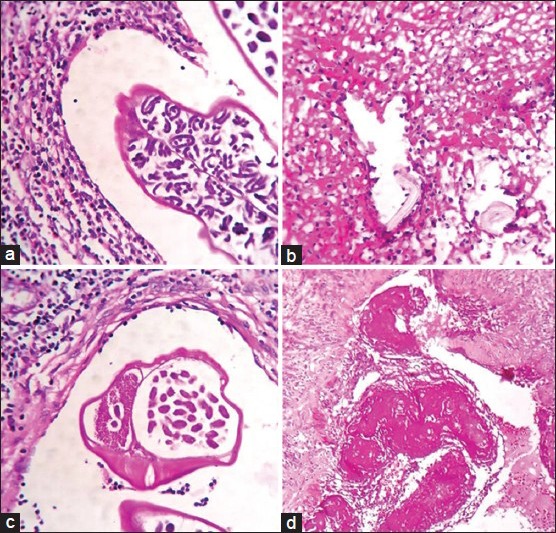

Figure 2.

Morphology of parasites. (a) Gravid worm in dilated lymphatics. (b) Dead microfilaria adherent to lymphatic wall. (c) Cross-section of gravid worm showing internal organs. (d) Dead worm entrapped with fibrinous material attached to lymphatic wall (H and E, ×100)

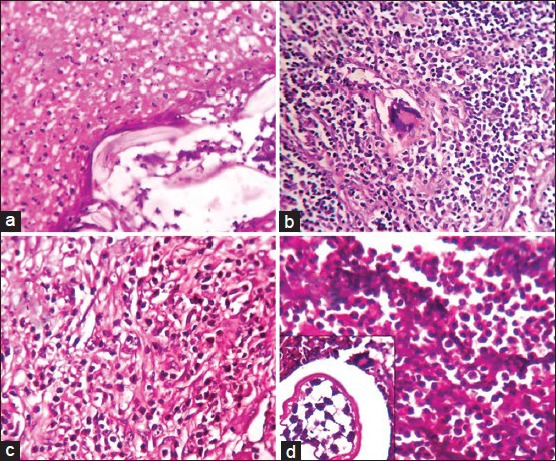

Figure 3.

Immune response. (a) Fibrinopurulent response around dead microfilariae. (b) Multinucleated giant cells in lymph node parenchyma. (c) Eosinophil rich granulation tissue. (d) Neutrophil collection and multinucleated giant cells (inset) (H and E, ×400)

Case 2

An 18-year-old male patient presented with a history of a right sided inguinal swelling of 6 months duration. On examination, a single discrete enlarged lymph node of 3 × 2 cm was palpated. Presumptive clinical diagnosis of tuberculosis was supported by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) findings of discrete granulomas comprising of multinucleated giant cells. The patient was given anti-tubercular therapy. The swelling didn’t respond to treatment and so was excised for histological evaluation. Histopathological slides from the single enlarged lymph node sent showed varying sized reactive follicles with germinal centers. Few multinucleated giant cells were seen in the lymph node parenchyma [Figure 3b]. Dilated perinodal lymphatic containing live gravid filarial worm was also seen [Figures 2a and 4a].

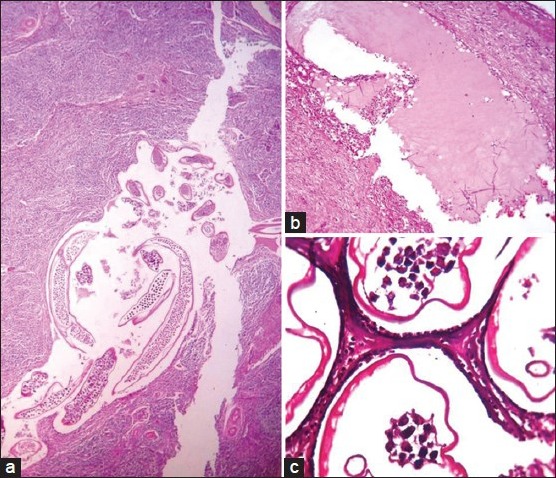

Figure 4.

Lymphatic architecture. (a) Dilated perinodal lymphatics (H and E, ×100). (b) Dilated lymphatic distant to the site of worm nest. (c) Lymphatics lined by endothelial cells having bulging nuclei (H and E, ×1000)

Case 3

A 44-year-old male presented with a history of progressively increasing swelling of the right side of scrotum which he noticed following a fall. On examination, a tender, fluctuant, firm to hard 10 × 10 cm mass was noted on the right side of the scrotum. Provisional diagnosis of hematoma was given. Scrotal exploration and evacuation was attempted with a paramedian incision. Fifty ml of blood clot and 150 ml of thick pus was drained out. Thickened spermatic cord and necrotic testicular tissue were noted. High inguinal orchiectomy was performed to rule out malignancy. Pus sent for microscopy showed gram positive cocci. No microfilariae were detected on peripheral smear. A large ruptured cyst impregnated with necrotic debris was noted in the paratesticular tissue [Figure 1b]. Gravid worm with numerous microfilariae within [Figure 2c] and dead filarial worms impregnated with fibrinous material were observed in the lumen of lymphatics [Figure 2d]. Granulation tissue [Figure 3c], neutrophilic abscess and sparse multinucleated giant cells [Figure 3d] were seen in adjacent peritesticular tissue. Altered lymphatic morphology with dilatation [Figure 4b] lined by bulging endothelial cells were seen [Figure 4c].

DISCUSSION

Lymphatic filariasis occurs in all ages and both sexes. None of our patients were females. Decreased incidence in females is explained as their body parts are clothed more, thus denying vectors their blood meal and a chance to transmit the disease.[4]

Individuals with filarial infection can be asymptomatic or symptomatic. Subclinical lymphangiectasia has been detected sonographically in asymptomatics. The absence of inflammation in lymphatic walls noted suggests that the lymphangiectasia in asymptomatic is mediated by parasite derived factors. Ectatic lymphatics can be detected at a distant site from the location of worms [Figure 4b], which indicates the role of some toxin or secretory product released by parasites acting on lymphatic endothelium to cause dilatation.[3,5,6]

Manifestations of filarial infection can be acute – acute filarial fever, acute dermatolymphangioadenitis (ADLA) or chronic pathologies like hydrocoele and elephantiasis.[2]

Acute filarial fever features a low grade fever with symptoms of lymphangitis. ADLA presents as plaque like such as lesions, systemic symptoms like fever with chills accompanying with adenopathy and ascending lymphangitis.[2] Acute filarial fever is believed to be the result of immunological response to dead or dying worms.[3,5,7] Secondary bacteremia underlies ADLA. Acute filarial fever is self-limiting, while ADLA predisposes to chronic pathologies. This implies, secondary bacteremias are prognostically important factor for progression to chronicity.[3]

The case series we present here comprises of chronic pathologies namely hydrocoele and inguinal lymphadenitis. These lesions clinically mimic other local diseases such as pyocoele, hematocoele, malignancy, and tuberculosis. No history suggestive of previous episodes of acute filarial infection was present. This further marauds the clinical diagnosis.

Section from all the cases revealed ectatic paratesticular lymphatics [Figure 4]. This conforms lymphangiectasia as an association and precursor lesion of chronic symptomatic disease.[6]

The transition from lymphangiectasia stage to chronic disease is driven by various factors like secondary bacterial infection, adult worm burden, location of adult worm, death of worm and type of immune response.[5,7]

Adult worm burden is considered as a compounding factor as prevalence of hydrocoele in population is found to correlate with intensity of infection. No arguments exist contradicting the notion that hydrocoele is caused by filarial worm. Adult worms have been detected consistently in intrascrotal lymphatics in cases of hydrocoele. Similarly, worms in afferent lymphatics are associated with lymphadenitis, lymphatic obstruction with resultant edema and secondary infection underlying elephantiasis.

Many animal models and observations strongly indicate that host immune response to dead worm forms the basis of pathogenesis of human disease. Factors intrinsic to parasite such as age, metabolic disturbance, disappearance of endosymbiotic intracellular Rickettsiae Wolbachia are linked to worm death.[7]

Viable adults are recognized by the presence of intact external membrane, a small intestine, testis or ovary [Figure 2c]. Use of fixatives like formaldehyde induces coiling of the worms. Dead parasites are seen connected to the vascular wall by fibrin strands [Figure 2d]. These have deformed ruptured membrane, fragmented parts or calcification.[5] Thus, histology doesn’t allow species identification as detailed morphology is not clearly evident in either viable or dead.[5,7] Capability of eosinophils in destroying parasites is unrivalled. Eosinophils in surrounding tissue [Figure 3c] indirectly suggest the presence of dead parasites.[5]

The third case showed both live and dead parasites together in the same lymphatic vessel despite adjacent vigorous inflammatory response. Such an occurrence has also been explained in previous reviews. This confirms that immune response doesn’t mediate death of parasite but it is the effect of parasitic death.[5,6]

The immune response to filaria is composed of varied number of eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells and large macrophages gathering around the dead parasite. In later stages, true granulation tissue comprising of newly formed blood vessels permeated by inflammatory cells is seen [Figure 3c]. The function of this granulation tissue is claimed to be an elimination of source of insult, facilitation of tissue remodeling and restoration of normal architecture. This type of inflammation comprising eosinophils exemplifies Th 2 immune response. A purulent response with neutrophilic abscess [Figure 3a and d] has also been described as a rare occurrence.[5]

Injection of humans with lipopolysaccharide derived from Wolbachia bacteria stimulates T-cells with reduced capacity to produce interferon (IFN)-gamma and interleukin-2 which implies a shift towards Th 2 response.[8]

Wolbachia bacteria, like other Rickettsiae infects lymphatic endothelial cells inducing morphological and functional changes, namely bulging nuclei [Figure 4c], decreased number of intracytoplasmic vesicles transporting interstitial fluid culminating in edema.[5,6] The resultant endothelial cell injury leads to vascular leakage. Injury as trivial as a fall compounded by vascular fragility might be the cause of hematoma formed in our last case.

Granulomatous inflammation in lymph node along with afferent lymphatics having gravid worm was noticed in the younger patient [Figure 3b]. Innate immune response described in other rickettsial infection is of Th 1 type capable of inducing granulomas.[9] High levels of IFN-gamma, a Th 1 type cytokine are found in experimentally induced peritoneal granulomas caused by filariae in jirds. Polymerase reaction showed both bacterial and worm components within granulomatous tissue. This raises a possibility that Wolbachia could be an inciting agent for the causation of granulomas.[1]

It needs to be emphasized here that last of our cases showed multiple patterns of immune response - eosinophil rich granulation tissue, neutrophilic abscess and multinucleate giant cells. This implies that a single factor might have induced more than one type of immune response. Wolbachia released following the death of parasite as entailed above can induce all the described types of immune response. Presence of live parasite in asymptomatics indicates that parasites have evolved mechanisms to evade host recognition. Thus, it is likely that parasite factors are less potent in inciting such diverse immune response.[5]

Whilst, “hyporesponsive” microfilaremic patients are often asymptomatic, the amicrofilaremic individuals capable to mount the immune response suffer clinical manifestation.[10] Thus, peripheral smear examination for microfilariae is not prudent for diagnosis in symptomatic. Tissue examination by FNA or histology offers greater efficiency in diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

The pathogenesis of histological features in filarial infestation is complex. It is prudent to conclude that there exist different mechanisms underlying various types of host responses. The above discussion hints at Wolbachia not being merely an accomplice but an offender in histogenesis of filarial disease. Control of compounding factors like secondary bacterial infection can hinder progression onto chronic disease, thus contributing to decreased morbidity. Negative peripheral smear results should not deter clinicians in considering filariasis as diagnosis in symptomatic.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rao RU, Klei TR. Cytokine profiles of filarial granulomas in jirds infected with Brugia pahangi. Filaria J. 2006;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thakur BB, Sinha KC, Thakur S. Vol. 669. India: Medicine Update, API; 2005. Filariasis: An Appraisal; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melrose WD. Lymphatic filariasis: New insights into an old disease. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:947–60. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haleem A, Al Juboury M, Al Husseini H. Filariasis: A report of three cases. Ann Saudi Med. 2002;22:77–9. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2002.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figueredo-Silva J, Norões J, Cedenho A, Dreyer G. The histopathology of bancroftian filariasis revisited: The role of the adult worm in the lymphatic-vessel disease. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2002;96:531–41. doi: 10.1179/000349802125001348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennuru S, Nutman TB. Lymphatics in human lymphatic filariasis: In vitro models of parasite-induced lymphatic remodeling. Lymphat Res Biol. 2009;7:215–9. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2009.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dreyer G, Norões J, Figueredo-Silva J, Piessens WF. Pathogenesis of lymphatic disease in bancroftian filariasis: A clinical perspective. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:544–8. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor MJ, Cross HF, Ford L, Makunde WH, Prasad GB, Bilo K. Wolbachia bacteria in filarial immunity and disease. Parasite Immunol. 2001;23:401–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2001.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mcadam AJ, Sharpe AH. Infectious diseases. In: Kumar V, Abbas Ak, Fausto N, Aster JC, editors. Robbin and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 380–1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lymphatic filariasis: Diagnosis and pathogenesis. WHO Expert Committee on Filariasis. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71:135–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]