Abstract

Rational:

The role of Cryptosporidium as an agent of human diarrhea has been redefined over the past decade following recognition of the strong association between cases of cryptosporidiosis and immune deficient individuals (such as those with AIDS).

Purpose:

The purpose of this study is to determine the prevalence of enteric parasites and to compare the diagnostic utility of stool enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with various modifications of acid-fast (AF) staining in detection of Cryptosporidium in stool samples of diarrheic patients.

Materials and Methods:

Stool samples from 186 cases comprising of 93 HIV seropositive and 93 seronegative patients were included. These were subjected to routine and microscopic examination as well as various modifications of AF staining for detection of coccidian parasites and ELISA for the detection of Cryptosporidium.

Results:

The prevalence of enteric parasites was 54.8% and of Cryptosporidium was 17.2% in HIV seropositive patients while it was 29.0% and 5.4%, respectively in seronegative patients. Of the 186 cases, 33 cases (17.7%) were positive for Cryptosporidium by stool ELISA as compared to 21 (11.3%) by modified AF staining (gold standard) showing sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 92.7%, respectively. The maximum cases of Cryptosporidium (21; 11.3%) were detected by AF staining using 3% acid alcohol.

Conclusion:

ELISA is a simple, useful, and rapid tool for detection of Cryptosporidium in stool, especially for large scale population studies. However, the role of modified AF staining in detection of Cryptosporidium and other coccidian parasites is important. Based on the results of various modifications of AF staining, the present study recommends the use of 3% acid alcohol along with 10% H2SO4.

KEY WORDS: Cryptosporidium, HIV seropositive, HIV seronegative, modified acid-fast staining, stool ELISA

INTRODUCTION

Diarrhea is the most common gastrointestinal symptom reported in HIV-infected individuals.[1] Cryptosporidium is an agent of human diarrhea and a ubiquitous human pathogen.[2] Human cryptosporidiosis is usually self-resolving in immunocompetent individuals, while immunocompromised patients can develop life-threatening complications.[3]

Laboratory diagnosis of cryptosporidial infections based on detection of oocysts in the stool is labor intensive. This study was undertaken to compare the various modifications of acid-fast (AF) staining, to evaluate the diagnostic utility of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test, in detecting cryptosporidial infection and to determine the prevalence of intestinal parasites in HIV seropositive and seronegative patients with diarrhea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient selection

A total of 186 patients with diarrhea admitted in the wards or attending the outpatients department at a tertiary care hospital were investigated for enteric parasites in stool samples, with special emphasis on Cryptosporidium species. Of these, 93 were HIV seropositive and 93 were HIV seronegative patients. Three consecutive stool samples were collected from each case. Diarrhea of <2 weeks duration was termed as acute, 2-4 weeks as persistent and of >4 weeks as chronic diarrhea. This study was conducted during the period between January 2009 and August 2010 after approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee. The patients were instructed to collect the specimen in a clean wide mouthed plastic container with screw capped lid. Patients were asked to take care that the specimen should not get contaminated with water and/or urine, to include the mucus and blood tinged parts of feces and to submit the stool sample within 1 h of collection to the Microbiology Laboratory at this hospital.

Stool processing and examination

The color and consistency of the specimen was noted. The presence of adult worms, segments of worms, blood, and mucus were looked for. Samples were concentrated using Sheather's sucrose floatation technique.[4] Iodine and saline wet mounts prepared directly from the sample as well as following concentration were examined for the presence of helminthic eggs and larvae, protozoal trophozoites and cysts as well as Cystoisospora oocysts. Iodine mount was screened especially for yeast like unstained structures suggestive of Cryptosporidium oocysts. A total of five smears were prepared. These were subjected to various modifications of Kinyoun's AF staining (cold technique) using 1% acid alcohol,[5] 3% acid alcohol,[6] 1% H2SO4,[7] and 10% H2SO4[8] with methylene blue as the counterstain. In Gram stained smears, yeast cells (2-4 μm) with budding forms were noted. The shapes, sizes, and arrangement of such yeast cells were kept in mind while examining the smears stained by modified AF stain. The AF stained smears were examined first under low power objective for pink to red ellipsoidal structures (20-30 μm × 10-19 μm) suggestive of Cystoisospora belli. Under the oil immersion objective, pink to red, round to oval, isolated structures (4-6 μm) suggestive of Cryptosporidium species and pink to red spherical structures (8-10 μm) suggestive of Cyclospora species were looked for.[6] The specimens for ELISA were stored at −20°C without any preservative. Stool ELISA (RIDASCREEN Cryptosporidium, R-BioPharm, Germany) for the detection of cryptosporidial antigen was carried out as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Diagnostic criteria

Criteria for denoting a sample as Cryptosporidium positive or negative was based on microscopy.

Statistical methods

Sample size was calculated using “PSPP” software (version 0.6.0., the GNU Operating System. Free Software Foundation). “https://www.gnu.org/software/pspp/”. All statistical analysis were done using “OpenEpi Stat software version 2.3 (Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version 2.3. www.OpenEpi.com, updated 2009/20/05, accessed 2014/04/06.)”. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of the stool ELISA was calculated using modified AF staining of stool smears as the gold standard.

RESULTS

Of the total 186 patients, 93 were HIV seropositive and the remaining 93 were HIV seronegative cases. Parasites were detected in 51/93 (54.8%) HIV seropositive and 27/93 (29.0%) seronegative patients. The patients’ age ranged from 3 to 70 years. The maximum cases of diarrhea were seen in the age group of 21-40 years. There were 60 males and 33 females in both seropositive and seronegative groups. Cryptosporidium was detected in 16/51 HIV seropositive and in 5/27 HIV seronegative patients in whom parasites were seen.

HIV seropositive group

A total of 61 parasites, either as single or mixed infection, were detected in stool samples of 51/93 (54.8%) HIV seropositive patients. Protozoan parasites 39/61 (63.9%) were more common as compared to the helminthes 22/61 (36.1%). The most common parasite detected from the former group was Cryptosporidium in 16/93 (17.2%) cases [Table 1]. Cystoisospora belli was detected in two cases. In one of these two cases, it was detected along with Ascaris lumbricoides. Other enteric parasites detected included Giardia intestinalis 11.8%, Entamoeba histolytica 10.7%, Trichuris trichiura and Ascaris lumbricoides 7.5% each, Ancylostoma duodenale and Enterobius vermicularis 3.2% each and Strongyloides stercoralis 2.2% [Figure 1]. Out of 16 cases with Cryptosporidium, 9/93 (9.7%) were cases of single infection and 7/93 (7.5%) of mixed infection. Among the 51 patients, 35.3% had acute diarrhea and 64.7% had chronic diarrhea. None presented with persistent diarrhea. Abdominal pain and fever were present in 21.6% patients, with significant weight loss in 15.7% and vomiting in 13.7% patients. Chronic diarrhea was noted in 6/9 (66.7%) cases of single infection with Cryptosporidium and in only 2/7 (28.8%) cases of mixed infections. All the 16 cases, in which Cryptosporidium was detected, had CD4 counts ≤200 [Table 2].

Table 1.

Prevalence of Cryptosporidium in HIV seropositive and HIV seronegative groups (n=186)

Figure 1.

Parasites detected in stool samples of HIV seropositive (n = 93) and seronegative group (n = 93). Key for Crypto = Cryptosporidium, Giardia = Giardia intestinalis, EH = E. histolytica, Iso = Cystoisospora belli, AL = Ascaris lumbricoides, TT = Trichuris trichiura, AD = Ankylostoma duodenale, EV = Enterobius vermicularis, SS = Strongyloides stercoralis

Table 2.

Correlation between CD4 count and number of HIV seropositive cases in which Cryptosporidium was detected (n=93)

HIV seronegative group

A total of 29 parasites, either as single or mixed infection, were detected in 27 (29%) of the HIV seronegative patients. Protozoan parasites 17/29 (58.6%) were more common as compared to the helminthes 12/29 (41.4%). Cryptosporidium was detected in 5/93 (5.4%) cases preceded only by Giardia intestinalis in 7/93 (7.5%) [Table 1]. The other enteric parasites detected included Entamoeba histolytica 5.4%, Ancylostoma duodenale 4.3%, Trichuris trichiura, and Ascaris lumbricoides 3.2% each, with Enterobius vermicularis and Strongyloides stercoralis 1.1% (1/93) each [Figure 1]. Cystoisospora belli was not detected in this group. Three of the Cryptosporidium cases were single infections while two were mixed infections with Giardia intestinalis. Of the total 27 HIV seronegative patients in whom parasites were detected, 25.9% had acute, 11.1% had persistent while 62.9% had chronic diarrhea. Abdominal pain and vomiting were present in 22.2% patients with significant weight loss in 25.9% and fever in 14.8% patients. In cases with Cryptosporidium, persistent diarrhea was noted in 3/5 (60%) cases with acute diarrhea and chronic diarrhea present in 1/5 (20%) each. All the HIV seronegative patients were apparently immunocompetent. None gave history of any condition suggestive of immunosuppression or history of renal transplant.

In children

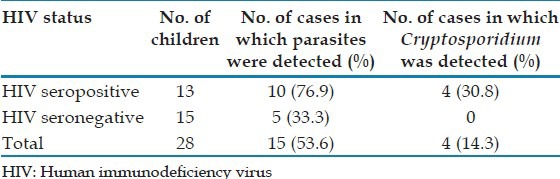

Parasites were detected in 53.6% of 28 children in the study, as shown in Table 3. Cryptosporidium was detected in 4/13 (30.7%) HIV seropositive children. It was not detected among the 15 HIV seronegative children.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Cryptosporidium in children (n=28)

Comparison of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and microscopy for diagnosis of Cryptosporidium in stoo

The performance of stool ELISA was evaluated using modified AF staining as the gold standard. While 33 cases were positive for Cryptosporidium by stool ELISA, 21 of these were positive by modified AF staining [Figure 2]. All samples negative by ELISA were also negative by modified AF staining. However, 12 samples negative for Cryptosporidium by modified AF staining were positive by stool ELISA. Sensitivity and specificity of stool ELISA for detection of Cryptosporidium was 100% and 92.7%, respectively with positive predictive value, 63.6% and negative predictive value, 100% [Table 4]. The present study has also compared the various modifications of AF staining. Using 3% acid alcohol, maximum cases (21; 11.3%) of Cryptosporidium were identified, whereas 10% H2SO4 identified Cryptosporidium in seven (7; 3.8%) of these cases. Cystoisospora belli was detected in two cases only, both by modified AF staining technique using 10% H2SO4 [Figure 3], while Cyclospora was not detected at all [Table 5]. Modification using 1% acid alcohol and 1% H2SO4 did not detect any of the coccidian parasites in the present study.

Figure 2.

Oocyst of Cryptosporidium species by modified acid-fast staining (3% acid alcohol modification), ×1000

Table 4.

Comparison of ELISA with modified AF stain for the detection of Cryptosporidium in stool samples (n=186)

Figure 3.

Oocyst of Cystoisospora belli by modified acid-fast staining (using 10% H2SO4), ×1000

Table 5.

Comparison of the various modifications of the AF stain in detection of coccidian parasites (n=186)*

DISCUSSION

Of 93 HIV seropositive cases, enteric parasites were detected in 51 (54.8%) cases. Banerjee et al. have reported enteric parasites in 57.3% of 258 cases while Kulkarni et al. have reported in 35% of 137 HIV-infected cases.[9,10] Cryptosporidium was found to be the most common parasite associated with diarrhea in this group (16/93;17.2%). Among the HIV seropositive cases reported in various Indian studies, prevalence of Cryptosporidium has ranged from 2.9% in south India to 46.6% in north eastern part of India.[11,12] Two studies from Mumbai have reported prevalence of 31% and 8.5%, respectively.[13,14] The low prevalence of Cystoisospora belli in HIV seropositive group may be due to the availability of co-trimoxazole. There is frequent use of this drug for therapy or prophylaxis of Toxoplasma, Pneumocystis jirovecii, and Cystoisospora infections. When stratified by CD4 counts, all 16 patients with Cryptosporidium had counts <200 cells/cmm. Similar findings have been noted by studies from Delhi and Pune.[15,10] This reinforces the importance of CD4 T cells in mediating resistance to this pathogen.[3]

In the HIV seronegative group, enteric parasites were detected in 27 (29%) of the patients. Giardia was the commonest parasite detected (7.5%) followed by Cryptosporidium (5.4%). Banerjee et al. from south India have reported a lower parasite prevalence of 5.8% and Cryptosporidium in 0.37% in their study while Nagamani et al. have reported Cryptosporidium in 0.12% of symptomatic adults.[9,16]

Cryptosporidium was detected in 4/13 (30.7%) HIV seropositive children in the present study. It was not detected among the seronegative children while Indian studies have reported positivity rates ranging from 1.1% to 18.9% in malnourished as well as immunocompetent patients,[3] indicating that the pathogen does not need an opportunity to cause infection.

In the present study, maximum cases (21; 11.3%) of Cryptosporidium were identified by modified AF staining using 3% acid alcohol. ELISA detected 12 more positives over microscopy. These may imply real current infection or an ability to detect free antigen from some extracellular lifecycle stage. In these cases, the ELISA may have detected cryptosporidiosis more efficiently than other means of diagnosis and may be important in identifying persons not actively excreting oocysts at the time of specimen collection, which is relevant to the transmission of infection. Sensitivity and specificity of Stool ELISA for detection of Cryptosporidium compared with modified AF staining was 100% and 92.7%, respectively. A study from southern India by Jayalakshmi et al. have reported sensitivity and specificity of ELISA (Ridascreen® Cryptosporidium, R-Biopharm) to be 90.9% and 98.7%, respectively.[17] ELISA may have an advantage over microscopy esp. in large scale epidemiological studies, as all microscopic diagnoses rely on direct visualization and morphologic recognition of small-sized oocysts which may be scant in number, intermittently shed, or inconsistently stained.[18] ELISA test results can be read objectively on a spectrophotometer.[19] However, the value of microscopy in detecting other parasites in HIV-infected patients cannot be overlooked. Moreover, the first form of diagnosis of parasitic infections is still by light microscopy of stool by an experienced microscopist.[20] Sensitivity and specificity are important factors for the choice of a proper diagnostic method for Cryptosporidium detection, although other factors such as cost, simplicity and ease of interpretation of results are also important considerations. Awareness about the prevalence of various parasites can guide therapy and aid in planning and instituting appropriate control measures. Although nitazoxanide is licensed for use in cryptosporidiosis among immunocompetent patients, a recent meta-analysis found it to be ineffective in HIV.[21] In HIV-infected patients, anti-retroviral therapy greatly influences the outcome of cryptosporidiosis.[3] As treatment modalities are limited,[21] emphasis should be placed on using suitable household water treatment methods such as boiling (since chlorination by itself cannot remove the oocysts of protozoa such as Cryptosporidium spp. and Cyclospora cayetanensis from water),[22] sanitation and educating HIV-infected individuals and persons working in high-risk environments about their risk of infection and prevention.[23] Future research directions would include comparing the microscopy negative-ELISA Cryptosporidium positive cases with a confirmatory test such as polymerase chain reaction.

CONCLUSION

An ELISA test with high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of cryptosporidial antigen in stool, offers a diagnostic advantage compared to the laborious conventional direct microscopy esp. for large scale epidemiological studies. However, for direct microscopy, the present study recommends the use of 3% acid alcohol along with 10% H2SO4 for the detection of coccidian parasites in stool.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The Research Society, Topiwala National Medical College and BYL Nair Ch. Hospital, Mumbai provided support in the form of financial grant which partly supported the study

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Navin TR, Weber R, Vugia DJ, Rimland D, Roberts JM, Addiss DG, et al. Declining CD4+T-lymphocyte counts are associated with increased risk of enteric parasitosis and chronic diarrhea: Results of a 3-year longitudinal study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;20:154–9. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199902010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith NH, Cron S, Valdez LM, Chappell CL, White AC., Jr Combination drug therapy for cryptosporidiosis in AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:900–3. doi: 10.1086/515352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ajjampur SS, Sankaran P, Kang G. Cryptosporidium species in HIV-infected individuals in India: An overview. Natl Med J India. 2008;21:178–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lumsden WH, Burns S, McMillan A. Protozoa. In: Collee JG, Fraser AG, Marmion BP, Simmons A, editors. Mackie and MacCartney Practical Medical Microbiology. 14th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1996. pp. 721–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parija SC. Text and Colour Atlas. 3rd ed. New Delhi, Chennai, India: All India Publishers and Distributors; 2009. Common laboratory methods in parasitology. In: Textbook of Medical Parasitology: Protozoology and Helminthology; pp. 360–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forbes BA, Sahm DF, Weissfeld AS. Laboratory methods for diagnosis of parasitic infections. In: Forbes BA, Sahm DF, Weissfeld AS, editors. Bailey and Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology. 11th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Inc; 2002. pp. 604–709. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp SE. Reagents, stains and media: Parasitology. In: Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, Landry ML, Pfaller MA, editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 9th ed. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2007. pp. 2013–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DPDx Diagnostic Procedures for Stool specimens-Specimen Staining. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 17]. Available from: http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/DiagnosticProcedures.htm .

- 9.Banerjee I, Primrose B, Roy S, Kang G. Enteric parasites in patients with diarrhoea presenting to a tertiary care hospital: Comparison of human immunodeficiency virus infected and uninfected individuals. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulkarni SV, Kairon R, Sane SS, Padmawar PS, Kale VA, Thakar MR, et al. Opportunistic parasitic infections in HIV/AIDS patients presenting with diarrhoea by the level of immunesuppression. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:63–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vignesh R, Balakrishnan P, Shankar EM, Murugavel KG, Hanas S, Cecelia AJ, et al. High proportion of isosporiasis among HIV-infected patients with diarrhea in southern India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:823–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anand L, Brajachand NG, Dhanachand CH. Cryptosporidiosis in HIV infection. J Commun Dis. 1996;28:241–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lanjewar DN, Rodrigues C, Saple DG, Hira SK, DuPont HL. Cryptosporidium, isospora and strongyloides in AIDS. Natl Med J India. 1996;9:17–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi M, Chowdhary AS, Dalal PJ, Maniar JK. Parasitic diarrhoea in patients with AIDS. Natl Med J India. 2002;15:72–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadraei J, Rizvi MA, Baveja UK. Diarrhea, CD4+ cell counts and opportunistic protozoa in Indian HIV-infected patients. Parasitol Res. 2005;97:270–3. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagamani K, Rajkumari A, Gyaneshwari Cryptosporidiosis in a tertiary care hospital in Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2001;19:215–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayalakshmi J, Appalaraju B, Mahadevan K. Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunoassay for the detection of Cryptosporidium antigen in fecal specimens of HIV/AIDS patients. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51:137–8. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.40427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ungar BL. Enzyme-linked immunoassay for detection of Cryptosporidium antigens in fecal specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2491–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.11.2491-2495.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston SP, Ballard MM, Beach MJ, Causer L, Wilkins PP. Evaluation of three commercial assays for detection of Giardia and Cryptosporidium organisms in fecal specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:623–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.623-626.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De A. Current laboratory diagnosis of opportunistic enteric parasites in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Trop Parasitol. 2013;3:7–16. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.113888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai NT, Sarkar R, Kang G. Cryptosporidiosis: An under-recognized public health problem. Trop Parasitol. 2012;2:91–8. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.105173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peletz R, Mahin T, Elliott M, Montgomery M, Clasen T. Preventing cryptosporidiosis: The need for safe drinking water. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:238–8A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.119990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fletcher SM, Stark D, Harkness J, Ellis J. Enteric protozoa in the developed world: A public health perspective. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:420–49. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05038-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]