Abstract

Background:

L-citrulline is an amino acid discovered in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus, Cucurbitaceae) and is a known component of the nitric oxide (NO) cycle that plays an important role in adjusting blood circulation and supplying NO and a key component of the endothelium-derived relaxing factor.

Objective:

The objective of this study is to evaluate the effect of L-citrulline on a newly established stress-induced cold hypersensitivity mouse model.

Materials and Methods:

When normal mice were forced to swim in water at 25°C for 15 min, their core body temperature dropped to 28.9°C, and then quickly recovered to normal temperature after the mice were transferred to a dry cage at room temperature (25°C). A 1-h immobilization before swimming caused the core body temperature to drop to ca. 24.1°C (4.8°C lower than normal mice), and the speed of core body temperature recovery dropped to 57% of the normal control. We considered this delay in recovery from hypothermia to be a sign of stress-induced cold hypersensitivity. Similar cold hypersensitivity was induced by administration of 50 mM L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester, a NO synthesis inhibitor.

Results:

In this study, we showed that recovery speed from the stress-induced hypothermia remarkably improved in mice fed a 1% L-citrulline-containing diet for 20 days. Furthermore, the nonfasting blood level of L-arginine and L-citrulline increased significantly in the L-citrulline diet group, and higher serum nitrogen oxide levels were observed during recovery from the cold.

Conclusions:

These results suggested that oral L-citrulline supplementation strengthens vascular endothelium function and attenuates stress-induced cold hypersensitivity by improving blood circulation.

Keywords: Citrullus lanatus, cold hypersensitivity, Cucurbitaceae, L-citrulline, nitric oxide

INTRODUCTION

Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus [Thunb] Matsum. et Nakai; syn. Citrullus vulgaris schrad[1]) is a rich natural source of the nonessential amino acid L-citrulline. L-citrulline content in watermelon flesh ranges from 3.9 to 28.5 mg/g dry weight and 1.1 to 4.7 mg/g fresh weight,[2,3] and rind contains more citrulline than flesh based on dry weight, but it contains a little less based on fresh weight. L-citrulline is not a structural protein, but it can be metabolized to L-arginine, a conditionally essential amino acid.[4] Collins et al.[5] have reported that consumption of 780 or 1560 g of watermelon juice/day, which provided 1 or 2 g of L-citrulline, respectively, increased the fasting concentration of plasma arginine by 12-22% in healthy humans. Although L-arginine is a direct substrate used in the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) in the NO cycle, it is easily metabolized in the small intestine and liver when administered orally. Contrary, L-citrulline is not metabolized in the small intestine and liver, and mostly circulates as a free amino acid, which is then converted into L-arginine in the kidney. Furthermore, arginine seem to be vulnerable to oxidation,[6] L-citrulline is an efficient hydroxyl radical scavenger.[7] Therefore, L-citrulline is expected to be an efficient source of L-arginine, and play an essential role in the maintenance of vascular function. In rabbits fed a high-cholesterol diet, ingestion of L-citrulline (2% in drinking water) for 12 weeks led to a marked improvement in endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation and blood flow, a dramatic regression in atheromatous lesions, and a decrease in superoxide production and oxidation-sensitive gene expression.[8] In Zucker diabetic fatty rats, drinking water containing 63% watermelon pomace juice for 4 weeks increased serum concentrations of arginine; reduced-fat accretion; lowered the serum concentrations of glucose, free fatty acids, homocysteine, and dimethylarginine; enhanced guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase-I activity and tetrahydrobiopterin concentrations in the heart; and improved acetylcholine-induced vascular relaxation.[9] Perinatal supplementation with citrulline in drinking water (L-citrulline, 2.5 g/L) increased renal NO at 2 weeks and persistently ameliorated the development of hypertension in females and until 20 weeks in males.[10] In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled parallel-group trial, L-citrulline supplementation (5.7 g/day for 1 week) significantly increased plasma citrulline, arginine, and serum nitrogen oxide (NOx). Because of the correlation between the plasma arginine increase and a reduction in baPW, short-term L-citrulline supplementation may functionally improve arterial stiffness.[11] The swelling of the lower leg in females during long-term seating was also reduced by oral L-citrulline supplementation.[12] Thus, there is growing evidence that oral L-citrulline could be an effective supplier of endothelial NO through the L-citrulline/L-arginine pathway and consequently improve various cardiovascular diseases.

Since NO counteracts norepinephrine-dependent vascular contraction,[13] the stress-induced reaction of an overactivated sympathetic nervous system may be significantly attenuated by prior exposure to a NO supplier. However, little is known about the efficacy of L-citrulline on stress-induced physiological changes.

In this study, we established a stress-induced cold hypersensitivity model in mice and evaluated the ameliorating effects of alimentary L-citrulline.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All the experiments were performed with 5-week-old male ddY mice (Japan SLC, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The animals were maintained at the Laboratory Animal Research Center of Kitasato University, housed in polycarbonate cages with a 12 h: 12 h light-dark cycle at 55% ±5% humidity and an ambient temperature of 22°C ± 1°C, and the mice had access to food and water ad libitum. During the acclimation, standard diet (CE-2; CLEA Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and water were provided ad libitum for at least 3 days. Animal protocols were approved by the Kitasato University School of Pharmaceutical Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee (approval number F10-1, 07 July 2010), and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Drugs

L-citrulline (purity >98.5%) was obtained from Kyowa Hakko Bio Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). The L-citrulline-containing experimental diet was prepared as a 1% L-citrulline-containing CE-2-based pellet diet by CLEA Japan Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). The control diet was prepared by substituting cornstarch for the L-citrulline.

L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME hydrochloride, purity >98.0%; Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was dissolved in saline and administered intraperitoneally 1 h prior to the forced cold-water swimming. The dosage of L-NAME was determined according to preliminary experiments.

Preparation of the stress-induced cold hypersensitivity model

The mice were fasted for 18 h, but were allowed free access to water. They were then placed in the restraint cages (Natsume Seisakusho Co. Limited, Tokyo, Japan) and immersed vertically up to the neck in warm water (37°C ± 1°C) for 1 h, before a mild cold-exposure. Hypothermia was induced by a mild cold exposure by placing individual mice in a tank of water (depth = 12 cm, temperature = 25°C ± 1°C) for 15 min. The mice were forced to swim in the tank and then the water was wiped from the body surface and the mice were transferred to a dry cage at room temperature (25°C ± 1°C).

Although the 1-h immobilization stress both with and without warm water immersion at 37°C showed similar effects, the former showed better reproducibility of the results (data not shown). Therefore, we adopted the 1-h immobilization stress with warm water immersion as a stress load method.

Assessment of cold hypersensitivity

Cold hypersensitivity induced by a 1-h immobilization was evaluated by monitoring the time course of changes in core body temperature and peripheral body surface temperature after cold exposure in comparison to that of the normal mice without the immobilization stress preconditioning.

The core body and peripheral body surface temperatures were measured with a wireless thermometer (electronic identification transponder and digital control system - 5001 handheld Reader Systems; Bio Medic Data Systems, Inc., Seaford DE, USA) and an infrared thermal radiometric camera (MobIR M3; IRSYSTEM CO., LTD, Tokyo, Japan), respectively, to avoid disturbing the mice by handling.

Wireless thermometer implantation

Under anesthetization with pentobarbital, a wireless thermometer was implanted in the abdominal cavity of a mouse. The mouse was then given free access to food and water for at least 3 days to recover from the surgical operation.

Measurement of spontaneous motor activity

Spontaneous motor activity was measured using a passive infrared sensor detection system (Supermex CompACT AMS; Muromachi Kikai Co., Limited, Tokyo, Japan) as we reported previously.[14]

Measurement of plasma nitrate and amino acid concentrations

Measurement of plasma nitrate was conducted according to a previously reported method with a slight modification.[15] Each blood sample in 1 mg/ml ethylenediaminetetraacetate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C to separate the plasma. To remove the plasma proteins, an equal volume of methanol was added to the plasma sample, mixed well, and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min. The concentrations of NOx in the supernatant were measured with a NOx analyzer (ENO-20; Eicom Corporation, Kyoto, Japan).

Plasma amino acid determinations were performed in an AminoTac JLC-500/V analyzer using a multi-segment tandem column (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) according to previously reported methods.[16,17]

Measurement of serum cortisol

Serum cortisol levels were measured using the cortisol express enzyme immunoassay Kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Michigan, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation values. The Student's t-test (unpaired) was employed to evaluate statistical differences. P <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. P values are shown as *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

RESULTS

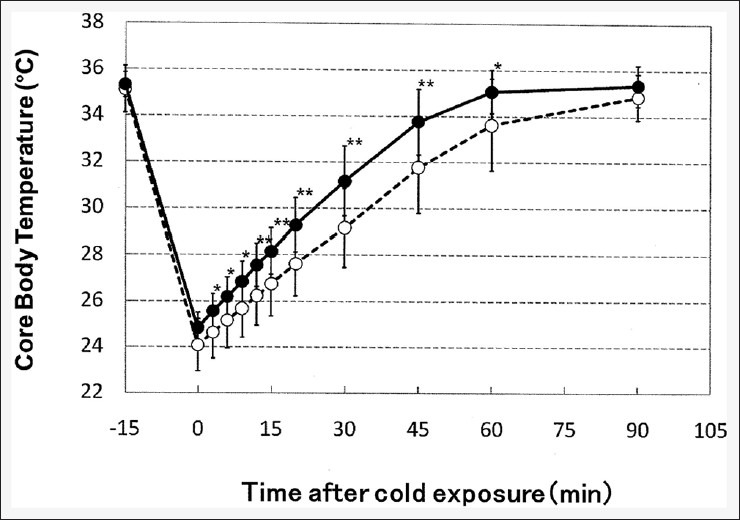

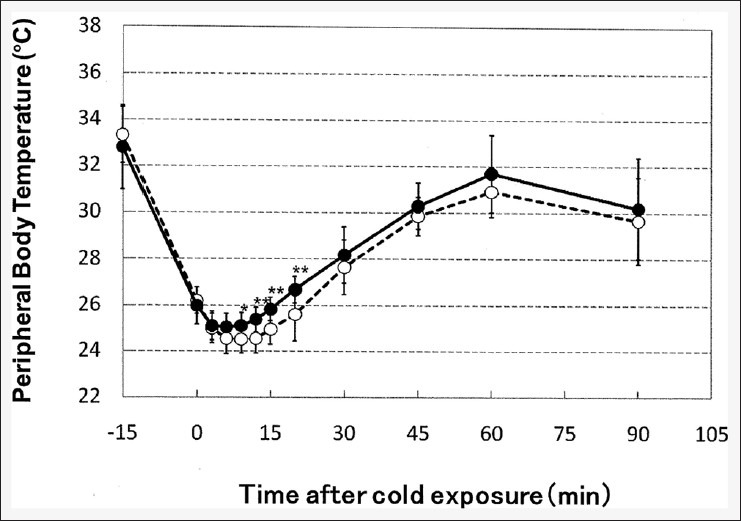

In this experiment, forced swimming in cold water was used as a mild cold exposure. The body temperature of the mice dropped to 28.9°C when forced to swim for 15 min in water at 25°C. After the mice were transferred to a dry cage and left at room temperature, their core body temperature recovered to normal temperature within 20 min [Figure 1]. In contrast, a 1-h immobilization with a warm water (37°C) immersion prior to the forced cold-water swimming resulted in a drop in core body temperature that was 4.8°C lower than that in mice without the immobilization stress. The time required for the recovery of core body temperature in mice with immobilization stress was 3-times longer than that in mice without the immobilization stress. Recovery speed during the first 15 min was 0.40°C/min in the normal mice and 0.23°C/min in the mice exposed to the immobilization stress. The change in peripheral body surface temperature also showed a similar trend [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Time course of the changes in core body temperature after cold exposure with (open circles) or without (closed triangles) immobilization stress preconditioning. Values shown are the means ± standard deviation (n = 4). Statistical analysis: Unpaired t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. the control)

Figure 2.

Time course of changes in the tail skin surface temperature after cold exposure with (open circle) or without (closed triangle) preconditioning with immobilization stress. Values shown are mean ± standard deviation (n = 4). Statistical analysis: Unpaired t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. the control)

The cold hypersensitivity induced by the immobilization stress was similar to that induced by the administration of 50 mg/kg L-NAME, a NO synthesis inhibitor. Administration of L-NAME 1 h prior to the forced swimming in cold-water caused the core body temperature to drop 2.4°C lower than that in the control mice after forced swimming, and the time for the core body temperature recovery was delayed to 60 min [Figure 3]. Recovery speed during the first 15 min was 0.32°C/min in the control mice and 0.23°C/min in the mice administered L-NAME. The change in peripheral body surface temperature after administration of L-NAME also showed a similar trend [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

The effects of single administration of L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME) on the time course of changes in core body temperature after cold exposure without immobilization stress preconditioning. L-NAME was administered intraperitoneally 1 h prior to forced cold-water swimming. Open triangles: L-NAME, closed triangles: Vehicle. Values shown are the means ± standard deviation (n = 6). Statistical analysis: Unpaired t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. the control)

Figure 4.

The effects of administration of a single L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME) dose on the time course of changes in tail skin surface temperature after cold exposure without immobilization stress preconditioning. L-NAME was administrated intraperitoneally 1 h prior to forced cold-water swimming. Open triangles: L-NAME, closed triangles: Vehicle. Values shown are the means ± standard deviation (n = 6). Statistical analysis: Unpaired t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. the control)

Recovery from stress-induced cold hypersensitivity improved significantly in mice fed 1% L-citrulline-containing diet for 20 days [Figures 5 and 6]. In the L-citrulline diet group, the decrease in core body temperature after forced cold-water swimming was slightly (0.8°C) less than that in the control diet group. Recovery speed during the first 15 min improved 22%, and the time required for full recovery of core body temperature was shortened by 30 min [Figure 5]. Recovery speed during the first 15 min was 0.22°C/min in the L-citrulline diet group and 0.18°C/min in the control diet group. Although intake of the citrulline diet for 20 days did not affect body weight, food intake, or spontaneous motor activity, the nonfasting blood levels of L-arginine and L-citrulline increased [Table 1].

Figure 5.

The effects of an L-citrulline-containing diet on the time course of changes in core body temperature after cold exposure with immobilization stress preconditioning. Closed circles: L-citrulline diet, open circles: Control diet. Values shown are the means ± standard deviation (n = 12). Statistical analysis: Unpaired t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. the control)

Figure 6.

The effects of an L-citrulline-containing diet on the time course of changes in tail skin surface temperature after cold exposure with immobilization stress preconditioning. Closed circles: L-citrulline diet, open circles: Control diet. Values shown are the means ± standard deviation (n = 12). Statistical analysis: Unpaired t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. the control)

Table 1.

Comparison of body weight, food intake, serum arginine, serum citrulline, and spontaneous motor activity between mice fed the L. citrulline diet group and the control diet group

Furthermore, higher serum NOx (the sum of nitrite plus nitrate) was observed during recovery from hypothermia in the L-citrulline diet group [Figure 7; P = 0.09 at 5 min], and the area under the curve of NOx level was 1.16 times higher in the mice in the L-citrulline diet group.

Figure 7.

The effects of an L-citrulline-containing diet on the time course of changes in serum nitrogen oxide (NOx) levels after cold exposure with immobilization stress preconditioning. Closed circles: L-citrulline diet, open circles: Control diet. Values shown are the means ± standard deviation (n = 6-8). Statistical analysis: Unpaired t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. the control)

Although a significant elevation in serum cortisol was induced after forced cold-water swimming, there was no significant difference in serum cortisol levels between the control diet group and the L-citrulline diet group (before forced swimming 0.77 ± 0.37 ng/ml and 0.81 ± 0.32 ng/ml, respectively; after forced swimming 2.06 ± 0.43 ng/ml and 2.01 ± 0.42 ng/ml, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The results obtained in this study suggested that alimentary L-citrulline strengthens vascular endothelium function through the enhancement of endothelial NO supply during recovery from the cold, improves blood circulation, and attenuates stress-induced cold hypersensitivity.

In Japan, there is a symptom commonly referred to as Hiesho, which can be defined as hypersensitivity to cold in a particular part of the body. It frequently occurs in winter, and more than 30% of women in all age groups suffer from it. The mechanism of Hiesho has not been sufficiently elucidated; however, it is thought to be a type of circulatory disturbance caused by vasoconstriction of peripheral arteries.[18] In addition, at least some women with this hypersensitivity have characteristics of sympathetic hyperactivity.[19] Hypersensitivity to cold is evaluated clinically by the ice water immersion test. Hypersensitivity with an inferior vasoconstriction reaction showed a much slower recovery of toe skin temperature after cold exposure.[19] In this paper, we established a stress-induced cold hypersensitivity model in mice. A 1-h immobilization stress resulted in a much slower recovery from hypothermia induced by a mild cold exposure. Because the 1-h immobilization and L-NAME administration induced similar cold hypersensitivity in mice, immobilization stress might disturb endothelial function in the peripheral arteries.

Peripheral arteries are classified as either superficial arteries or deep arteries. Cold induces vasoconstriction of the superficial arteries. Adrenergic function is thought to be involved in this cold-induced vasoconstriction, because inhibition of sympathetic adrenergic function significantly reduces the cutaneous vasoconstrictor response to direct local cooling.[20] Constriction of the cutaneous blood vessels in response to cooling is a protective physiological response that acts to reduce the loss of body heat.[21] In contrast, deep arteries in the rat hind limb were dilated upon exposure to cold.[22] Expansion of deep arteries delivers warm blood to cooled extremities. Less expansion leads to slower recovery to cold temperature. Both deep and superficial arteries are dilated during recovery from cold.

Dietary L-citrulline might function in the dilation of these arteries by strengthening endothelial function, because mice fed L-citrulline had reduced immobilization stress-induced cold hypersensitivity and elevated serum NOx levels. Similar effects of oral L-citrulline supplementation (6 g/day for 4 weeks) were reported by the cold pressor test in healthy human subjects.[23] In the cold pressor test, acute increases of brachial systolic blood pressure and aortic systolic blood pressure were observed during the immersion of the right foot up to the ankle in 4°C water for 2 min, and this could be translated as the results of sympathetic-mediated vasoconstriction. And oral citrulline attenuated these changes. Thus, the stress-induced cold hypersensitivity mouse model would be a useful tool for the evaluation of the endothelial function, blood circulation and thermoregulation improving agents, like L-citrulline.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (17500484 and 21500659).

Footnotes

Source of Support: The Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Renner SS, Pandey AK. The Cucurbitaceae of India: Accepted names, synonyms, geographic distribution, and information on images and DNA sequences. PhytoKeys. 2013;20:53–118. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.20.3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rimando AM, Perkins-Veazie PM. Determination of citrulline in watermelon rind. J Chromatogr A. 2005;1078:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarazona-Díaz MP, Viegas J, Moldao-Martins M, Aguayo E. Bioactive compounds from flesh and by-product of fresh-cut watermelon cultivars. J Sci Food Agric. 2011;91:805–12. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curis E, Nicolis I, Moinard C, Osowska S, Zerrouk N, Bénazeth S, et al. Almost all about citrulline in mammals. Amino Acids. 2005;29:177–205. doi: 10.1007/s00726-005-0235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins JK, Wu G, Perkins-Veazie P, Spears K, Claypool PL, Baker RA, et al. Watermelon consumption increases plasma arginine concentrations in adults. Nutrition. 2007;23:261–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lobo V, Patil A, Phatak A, Chandra N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4:118–26. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.70902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akashi K, Miyake C, Yokota A. Citrulline, a novel compatible solute in drought-tolerant wild watermelon leaves, is an efficient hydroxyl radical scavenger. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:438–42. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayashi T, Juliet PA, Matsui-Hirai H, Miyazaki A, Fukatsu A, Funami J, et al. l-Citrulline and l-arginine supplementation retards the progression of high-cholesterol-diet-induced atherosclerosis in rabbits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13681–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506595102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu G, Collins JK, Perkins-Veazie P, Siddiq M, Dolan KD, Kelly KA, et al. Dietary supplementation with watermelon pomace juice enhances arginine availability and ameliorates the metabolic syndrome in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J Nutr. 2007;137:2680–5. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.12.2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koeners MP, van Faassen EE, Wesseling S, de Sain-van der Velden M, Koomans HA, Braam B, et al. Maternal supplementation with citrulline increases renal nitric oxide in young spontaneously hypertensive rats and has long-term antihypertensive effects. Hypertension. 2007;50:1077–84. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.095794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochiai M, Hayashi T, Morita M, Ina K, Maeda M, Watanabe F, et al. Short-term effects of L-citrulline supplementation on arterial stiffness in middle-aged men. Int J Cardiol. 2012;155:257–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morita M, Kobayashi Y, Iizuka M, Kondo S, Morishita K. The effect of oral L-citrulline supplementation on swelling of the lower legs in young females. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 2012;40:787–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stefano GB, Murga J, Benson H, Zhu W, Bilfinger TV, Magazine HI. Nitric oxide inhibits norepinephrine stimulated contraction of human internal thoracic artery and rat aorta. Pharmacol Res. 2001;43:199–203. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi Y, Takahashi R, Ogino F. Antipruritic effect of the single oral administration of German chamomile flower extract and its combined effect with antiallergic agents in ddY mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;101:308–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuda S, Yasu T, Predescu DN, Schmid-Schönbein GW. Mechanisms for regulation of fluid shear stress response in circulating leukocytes. Circ Res. 2000;86:E13–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manders RJ, Koopman R, Sluijsmans WE, van den Berg R, Verbeek K, Saris WH, et al. Co-ingestion of a protein hydrolysate with or without additional leucine effectively reduces postprandial blood glucose excursions in Type 2 diabetic men. J Nutr. 2006;136:1294–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.5.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheikh K, Camejo G, Lanne B, Halvarsson T, Landergren MR, Oakes ND. Beyond lipids, pharmacological PPARalpha activation has important effects on amino acid metabolism as studied in the rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1157–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00254.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ushiroyama N. Chill sensation: Pathological findings and its therapeutic approach. Igaku No Ayumi (Journal of clinical and experimental medicine) 2005;215:925–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito G. Knowledge of the oriental medicine and acupuncture and moxibustion which is useful to an understanding of the autonomic disturbance. Neurol Ther. 2010;27:771–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JM, Yen TC, Zhao K, Kosiba WA. Sympathetic, sensory, and nonneuronal contributions to the cutaneous vasoconstrictor response to local cooling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1573–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00849.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teixeira CE, Webb RC. Cold-induced vasoconstriction: A Waltz pairing Rho-kinase signaling and alpha2-adrenergic receptor translocation. Circ Res. 2004;94:1273–5. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000131755.49084.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato F, Matsushita S, Hyodo K, Akishima S, Imazuru T, Tokunaga C, et al. Sex difference in peripheral arterial response to cold exposure. Circ J. 2008;72:1367–72. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Figueroa A, Trivino JA, Sanchez-Gonzalez MA, Vicil F. Oral L-citrulline supplementation attenuates blood pressure response to cold pressor test in young men. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:12–6. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]