Abstract

Background:

Simple febrile convulsion is the most common disease of the nervous system in children. There are hypotheses that iron deficiency may affect febrile convulsion and the threshold of neuron excitation.

Aims:

This study was conducted with the objective of finding the effects of iron deficiency anemia on simple febrile convulsion episodes.

Settings and Design:

The study was conducted at AmirKabir Hospital of Arak Medical Sciences University, Arak, Iran. This is a case-control study.

Materials and Methods:

In this study, 382 children who were selected according to our inclusion and exclusion factors, were divided into two groups of case (febrile convulsion) and control (other factors causing fever) by their cause of hospitalization. After fever subsided, 5 ml blood sample was taken from each child and complete blood count and iron profile tests were performed.

Statistical Analysis:

The results were interpreted using descriptive statistics and independent t-test. Results: The prevalence of anemia in the group with febrile convulsion was significantly less than that in the control group: 22.5% of the children in the group with febrile convulsion and 34% in the control group exhibited anemia (P < 0.001). Moreover, the group with febrile convulsion had significantly higher blood indices, such as Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, and MCHC, compared to the control group (P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

Iron deficiency can prevent febrile convulsion in children and probably increases the threshold of neuron excitation in fever.

Keywords: Child, febrile convulsions, Iron deficiency

Introduction

Febrile convulsion (FC) is the most common disorder in the nervous system of children and 2-5% of the total number of (or 4.8 out of every 1000) children become affected every year.[1] Febrile convulsion is defined as convulsion resulting from fever. It occurs in children of 6 months to 6 (full six) years of age, is accompanied by fever higher than 38°C, and does not involve symptoms of central nervous system infections or any other background causes.[1] Risk factors of this disorder include history of convulsion or FC in the family, head injuries, mothers who smoke or consume alcoholic beverages, and high fevers.[2,3,4,5,6] Since a risk of FC is the probability of its subsequent development into convulsion and epilepsy, various studies have been carried out with the purpose of identifying correctable risk factors to reduce the prevalence of FC and, hence, of epilepsy and convulsion.[2,3,7,8,9] Iron deficiency is the most common micronutrient deficiency and can decrease the production of hemoglobin and thus cause iron deficiency anemia (which is a correctable and remediable condition).[10] Iron is essential for the metabolism of brain and neurotransmitters, and in the production of myelin which is required for nerve cells and can change the amplitude and the threshold of neurons excitation.[11] Studies conducted on the role of iron deficiency in febrile convulsion have yielded completely conflicting results. In some of these studies, iron deficiency has been identified as a risk factor,[7,12,13] while in others it has been stated that iron deficiency increases the threshold of neuron excitation and thus can play a protective role against febrile convulsion.[14,15] Given these contradictory results, we decided to study the relationship between iron deficiency anemia and febrile convulsion in children hospitalized in Amir Kabir Hospital of Arak City.

Materials and Methods

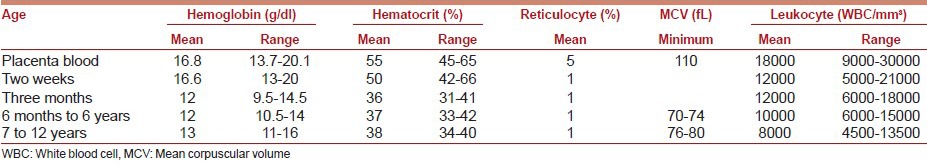

This case-control study involved 382 children aged from six months to 6 years, hospitalized in the pediatric ward of Amir Kabir Hospital of Arak from 2011 to 2013. They were divided into two groups of 191 children: the case group suffering from simple febrile convulsion and the control group afflicted with fever caused by any factor and without febrile convulsion. Children who had previous episodes of febrile convulsion, those with a diagnosed organic cause of convulsion, when the convulsion was a combined form, or there were delayed development, neurologic defects, central nervous system infection, Shigella gastroenteritis (based on the presence of white blood cells in feces or a history of bloody diarrhea), and when the parents did not co-operate well, were excluded from the study. At hospitalization, the children underwent careful physical and nervous system examinations by the assistants and emergency personnel of the pediatric ward, especially with respect to symptoms of meningeal irritation. Axillary temperatures of these children were measured at hospitalization and if these temperatures (when 0.5 degree was added to them) exceeded 38°C, they were included in the study. As an antipyretic, 10-15 mg/kg acetaminophen was administered every 4-6 hours for children whose body temperature exceeded 38°C. The case and control groups were matched with respect to age, sex, body temperature, development curve, and history of treatment with iron supplements. The family histories of children with respect to febrile convulsion and anemia were also checked and the related information was recorded. A convulsion accompanied by fever that lasted less than 15 minutes without local and focal symptoms was considered as a simple febrile convulsion. In cases where the presence of meningitis was suspected, a sample of the cerebrospinal fluid would be taken and, if meningitis was diagnosed, the child would be excluded from the study. After normalization of body temperature of all the afflicted children, in order to find cases of iron deficiency anemia, 5 ml blood sample was taken from each child for a complete blood count (CBC) and to measure the levels of serum iron, plasma ferritin, and TIBC (total iron binding capacity). In Table 1, the normal values of blood indices are listed. Children with blood indices less than those presented in Table 1 were considered to be suffering from iron deficiency anemia. Anemia is diagnosed when the hemoglobin level falls more than two standard deviations below the normal level of the related age group and sex. According to Table 1, if the hemoglobin level of the child (taking the age of the child into consideration) is lower than the normal range for the related age group, the child is considered to be afflicted with anemia. To separate iron deficiency anemia from other common causes of this condition, we used the CBC test and the levels of serum iron, plasma ferritin, and total iron-binding capacity. In iron deficiency, serum ferritin and plasma ferritin decline but TIBC rises. Serum iron concentrations of less than 40 mg/dl in children under 1 year of age and lower than 50 mg/dl in children over one year of age, ferritin levels of less than 7 mg/l, and TIBC values higher than 430 μg/dl confirm iron deficiency. Under these conditions, CBC will also show a fall in red blood cell indices (the number and the volume of the red blood cells and the mean hemoglobin concentration) and iron deficiency anemia develops. Children with anemia resulting from other causes (hemolysis, bleeding, thalassemia, etc.) were excluded from the study. The Ethics Council of Arak Medical Sciences University approved this study. All the parents or guardians of the sick children gave their written consent to their children taking part in the study; they could withdraw from the study anytime they desired. The researchers in this study were committed to the Helsinki Declaration at all stages of the study. Results of the experiments concerning the case and control groups were separately entered into the SPSS-19. Descriptive, distribution, and Chi-square tests were performed for the qualitative variables, and the independent t-student test was carried out (given that normal distribution was used in the K-S test) and P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Table 1.

Normal values of blood indices in various age groups of the children

Results

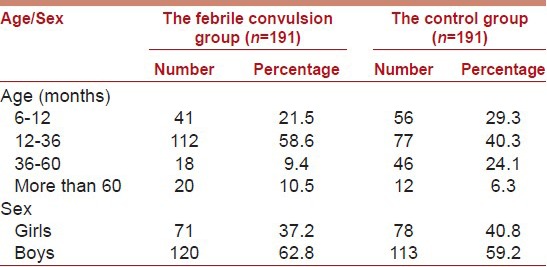

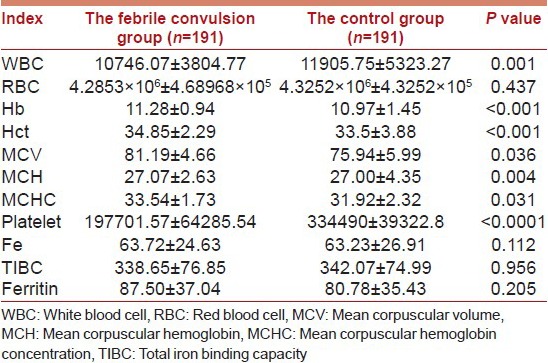

In the case and control groups, the highest frequency with regard to age was that of the milk-fed children aged from 12 to 36 months (58.6% of the case group and 40.3% of the control group). The ratios of the number of boys to girls in the two groups were similar (were not significantly different from each other) [Table 2]. Means of the blood indices of the febrile convulsion group, and their comparison with the corresponding means of the control group are listed in Table 3. As can be seen in this table, the means of Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, and MCHC in the febrile convulsion group were significantly higher than those in the control group. The means of Fe, TIBC, and ferritin in the febrile convulsion group were also higher than those in the control group but these differences were not significant. The mean RBC in the febrile convulsion group was higher than that of the control group, but this difference was not significant either. The WBC and platelet numbers in the febrile group were significantly lower than those in the control group. Forty-three patients in the febrile convulsion group and 65 patients in the control group suffered from iron deficiency anemia (and this was a significant difference at P < 0.001). In the febrile convulsion group, positive family episodes of convulsion were more frequent than in the control group (P < 0.001), but there were no significant differences between the two groups with regard to occurrences of anemia in the families (P = 0.476).

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of age and sex in the studied patients (the case and control groups)

Table 3.

Comparison of the means of blood indices, iron, ferritin, and TIBC of the febrile convulsion and control groups

Discussion

Given the effects of anemia, and especially those of iron deficiency anemia that is the most common type, it is possible that anemia influences occurrences of convulsion in these patients. Habits and diets of children play an important role in the absorption and storage of iron and in preventing iron deficiency anemia. There were no significant differences in the economic conditions of the families of the two groups of children studied. The patients who participated in this study were all breast-fed or given milk powder until they were 6 months old, and received solid food such as cereals, beans, carrot and vegetables soup, egg yolk, and fruit-juices after this age. Most children naturally adapted themselves to the program of three meals in a day by the time they were 1 year old. Moreover, the differences between the two groups regarding iron supplements were not significant. Taking the studies conducted into account, it can be said that there is a considerable difference of opinion concerning the relationship of anemia (particularly iron deficiency anemia) and febrile convulsion in children. Results of our study showed that the prevalence of anemia in the febrile convulsion group was considerably lower than that of the control group so that 22.5% of the children in the febrile convulsion group suffered from anemia, while 34.0% of the children in the control group were afflicted with it (P < 0.001). There were significant differences between the febrile convulsion group and the control group regarding blood indices such as Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, and MCHC as well, so that all these indices were higher in the febrile convulsion group as compared to the control group. The means of serum iron and serum ferritin in the febrile convulsion group were higher than the means of the control group, but these differences were not significant. The results of our study confirm those obtained by Kobrinski et al.[14] Talebian et al.[15] and Derakhshanfar et al.[16] Kobrinski et al.[14] conducted a case-control study in 1995 in which there were 25 children in the febrile convulsion group (as the case group) and 26 febrile children (who did not suffer from convulsion) in the control group. They found that iron deficiency anemia existed in 25.1% of the children in the case group but in 26.6% of the children in the control group, and concluded that iron deficiency anemia raises the threshold of the first febrile convulsion (and may even protect people against febrile convulsion). The first thing in their research that attracts attention is the small number of patients. Of course, they tried to solve this problem to some extent by matching interfering factors such as age, sex, history of convulsion in the family, body temperature, the number of white blood cells, the number of platelets, etc. We tried to select a suitable sample and to match factors that may influence the result as well. Talebian et al.[15] conducted a case-control study in Kashan in 2006 on 120 children less than 5 years of age. They reported that the probability of the occurrence of convulsion in children afflicted with anemia not only does not increase but it apparently decreases significantly, and that anemia may have a protective role against the occurrence of febrile convulsion. The sample volume in their research seems to be sufficient for a case-control study, although they give few details about matching of the studied groups. As we know, ferritin is an acute phase reactor that nonspecifically increases in response to any febrile illness.[17] Given that blood samples were taken to measure the levels of Fe, TIBC, and ferritin after the body temperature of the patients had been brought down to the normal level, the differences in ferritin levels between the two groups cannot be attributed to fever. In a study carried out on a sizable sample consisting of 1000 children (500 in the case group and 500 in the control group), Derakhshanfar et al.[16] studied the relationship between iron deficiency anemia and febrile convulsion. They found that the level of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in the control group were significantly higher than those in the case group, and concluded that the risk of febrile convulsion in children suffering from iron deficiency was less than the risk in other children. In their study, the criteria for excluding children from the study were only epilepsy, neuro-developmental disorders, other types of anemia, and current treatment with iron supplements. We also dealt with the factors causing fever because these factors can affect blood cell profiles. Results of our research, compared to those of the first two studies,[14,15] were achieved using more suitable risk factors and standardization, and a larger sample size was employed as well. Moreover, our results, compared to those obtained by Derakhshanfar et al.[16] are more reliable given our more suitable standardization and our more limiting criteria for including and excluding participants. In the study conducted by Derakhshanfar et al.[16] they attributed the probable reason for the protective role of iron deficiency to the role iron plays in the activity of exciting neurotransmitters such as monoamine oxidase and aldehyde oxidase. They added that the lack of iron leads to a reduction in the excitation power of the neurons and to a decline in the probability of excitation and convulsion in iron deficiency anemia, although their results contradict those obtained in other studies. In 1996, Pisacane et al.[13] conducted a case-control study on 156 children who were from six to 24 months of age in Naples in Italy and found that 30% of the patients in the febrile convulsion group and 14% in the control group exhibited anemia. They concluded that fever can deteriorate the negative effect of anemia on the brain and, hence, can cause convulsion. Their study is different from ours with respect to the age group of the patients and the control group. Their control group consisted of patients with febrile illnesses of the respiratory and digestive systems, while we had excluded children whose fever was due to digestive problems because diarrhea and vomiting, which occur in these children, can concentrate blood and mask anemia. Furthermore, if a person is afflicted with bloody diarrhea (resulting from, for example, shigellosis), he/she may develop anemia because of the loss of blood. Therefore, febrile diseases of the digestive system can distort the results obtained. In a case-control study conducted by Daoud et al. in Jordan[7] to investigate the role of iron deficiency anemia in the occurrence of the first febrile convulsion, there were 75 children in the febrile convulsion group and 75 children in the group without convulsion. They found that the average values of Hb and Hct, and the mean level of ferritin, were significantly lower in the febrile convulsion group compared to the control group, and attributed this difference to the probable role played by iron deficiency in the occurrence of febrile convulsion. These results have been repeated in other studies such as those carried out by Kumari et al.[12] Momen et al.[18] and Naveed al-Rahman and Billoo.[19] The differences between these studies and ours could be due to the fact that these researchers used different sample sizes and age groups of patients; they could be as well due to unsuitable standardization and failure to consider intervening factors such as the factors causing fever. Of course, the fact that we only studied hospitalized patients could be one of the limitations of our study. In designing the questions asked in our questionnaire, we divided the ages of the children into four classes. This limited our ability in obtaining the means of the different age groups and created problems in finding the normal levels of hemoglobin in the age group of less than 1 year old. Nevertheless, the normal values in this age group were matched in the case and control groups. Therefore, we suggest that in future studies numerical indicators be specified more accurately so that no data is lost (in other words, data should be perfectly distributed). Given the results of our study, it seems that iron deficiency anemia can prevent febrile convulsion probably through increasing the threshold of convulsion in patients with iron deficiency. If limitations specified in our study are eliminated, we can make more accurate decisions because deciding whether or not to correct anemia in children aged from six months to 6 years who are faced with the risk of febrile convulsion must be based on their clinical conditions and on the benefits and harms of not correcting anemia.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was financially supported by Arak University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Johnston MV. Seizures in childhood. In: Kleigman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BP, editors. Nelson Text Book of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. pp. 2013–2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH. Prenatal and perinatal antecedents of febrile seizures. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:127–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenwood R, Golding J, Ross E, Verity C. Prenatal and perinatal antecedents of febrile convulsions and afebrile seizures: Data from a national cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1998;12:76–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1998.0120s1076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Pediatrics Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Classifying recommendations for clinical practice guidelines. Pediatrics. 2004;114:874–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadleir LG, Scheffer IE. Febrile seizures. BMJ. 2007;334:307–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39087.691817.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management, Subcommittee on Febrile Seizures American Academy of Pediatrics. Febrile seizures: Clinical practice guideline for the long-term management of the child with simple febrile seizures. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1281–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daoud AS, Batieha A, Abu-Ekteish F, Gharaibeh N, Ajlouni S, Hijazi S. Iron status: A possible risk factor for the first febrile seizure. Epilepsia. 2002;43:740–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.32501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartfield DS, Tan J, Yager JY, Rosychuk RJ, Spady D, Haines C, et al. The association between iron deficiency and febrile seizures in childhood. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2009;48:420–6. doi: 10.1177/0009922809331800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg AT, Shinnar S, Shapiro ED, Salomon ME, Crain EF, Hauser WA. Risk f actors for a first febrile seizure: A matched case-control study. Epilepsia. 1995;36:334–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. A Guide for Program Managers. Geneva: WHO/NHD/013; 2001. Iron deficiency anemia. Assessment, prevention and control. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beard J. Iron deficiency alters brain development and functioning. J Nutr. 2003;133:1468–72S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1468S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumari PL, Nair MK, Nair SM, Kailas L, Geetha S. Iron deficiency as a risk factor for simple febrile seizures: A case control study. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:17–9. doi: 10.1007/s13312-012-0008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pisacane A, Sansone R, Impagliazzo N, Coppola A, Rolando P, D’Apuzzo A, et al. Iron deficiency anaemia and febrile convulsions: Case-control study in children under 2 years. BMJ. 1996;313:343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7053.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobrinsky NL, Yager JY, Cheang MS, Yatscoff RW, Tenenbein M. Does iron deficiency raise the seizure threshold? J Child Neurol. 1995;10:105–9. doi: 10.1177/088307389501000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talebian NM, Mosavi GA, Khojasteh MR. Relationship between febrile seizure and anemia. Iran J Pediatr. 2006;16:79–82. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derakhshanfar H, Abaskhanian A, Alimohammadi H, ModanlooKordi M. Association between iron deficiency anemia and febrile seizure in children. Med Glas (Zenica) 2012;9:239–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahdavi MR, Makhlough A, Kosaryan M, Roshan P. Credibility of the measurement of serum ferritin and transferrin receptor as indicators of iron deficiency anemia in hemodialysis patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011;15:1158–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Momen AA, Nikfar R, Karimi B. Evaluation of iron status in 9 months to 5 year old children with febrile seizures: A case control study in the south west of Iran. Iran J Child Neurol. 2010;4:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naveed-ur-Rehman, Billoo AG. Association between iron deficiency anemia and febrile seizures. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:338–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]