Abstract

Traumatic brain injury is a leading cause of morbidity and death in the pediatric population. In this study, we report a delayed unilateral traumatic brain swelling in a child with initial favorable evolution and sudden neurological deterioration after 4 days; highlighting clinical, physiopathological and radiological aspects of delayed unilateral brain swelling.

Keywords: Brain swelling, decompressive craniectomy, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the leading causes of morbidity and death in pediatric patients, and diffuse injury is the most common cause of death in this population.[1] The contribution of brain edema in cases of TBI remains a critical problem[2,3] and the role of the decompressive craniectomy in the management of severe brain injury and delayed cerebral edema (diffuse injury type III) is well studied.[4,5] However, patients admitted in excellent condition that develop significant neurological deterioration with unilateral brain swelling are unusual. The purpose of this study is to describe a rare case of a child who underwent decompressive craniectomy after severe TBI with delayed hemispheric brain swelling and discuss the physiopathological aspects of this condition based on a literature review.

Case Report

We report a case of a 4-year-old girl involved in a motor vehicle accident in which there was one fatal victim. The patient was found unconscious and orotracheal intubation was performed at the accident scene. She was admitted at the emergency department of our hospital 30 min after the accident and treated according to the advanced trauma life support protocol. The initial evaluation showed no signs of breathing or circulatory problems with normal vital signs. She was scored as 11 on the Glasgow coma scale (GCS 3-15) with isocoric pupils and normal light response.

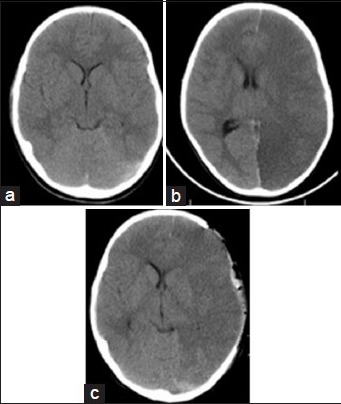

Thirty minutes after admission, a multislice head computed tomography (CT) scan was performed and showed a minimal midline shift of 2 mm to the right [Figure 1a]. We proceeded with the orotracheal extubation uneventfully, and the re-evaluation showed GCS score of 15, with pupils equal, round and reactive to light.

Figure 1.

(a) The first head computed tomography (CT) scans showed a minimal midline shift 2 mm. (b) Second CT scan is showing brain swelling hemispheric with midline shift and signs of herniation performed after 4 days. (c) Postoperative head CT scan with improvement of midline shift after decompressive craniotomy

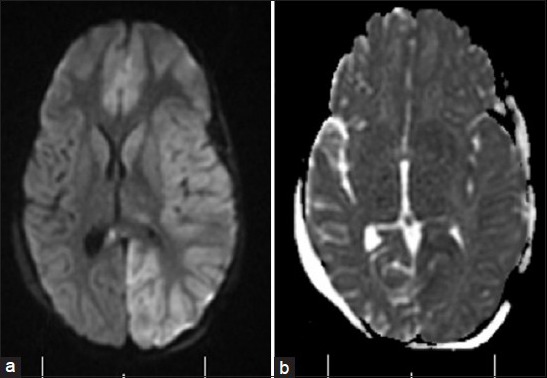

The patient evolved clinically stable and on day 4 after trauma, she presented with worsening of the neurological status with score 8 in the GCS, anisocoric pupils (left > right), and right hemiplegia. A new CT scan showed a hypodensity on the left cerebral hemisphere with a significant midline shift and signs of uncal herniation [Figure 1b]. An emergency decompressive craniectomy was performed [Figure 1c], with subsequent clinical management of intracranial hypertension at the pediatric intensive care unit. After the surgery, an early transcranial Doppler and brain angiogram showed no vascular abnormalities. On day 6 after trauma, a postoperative magnetic resonance study confirmed the diagnosis of brain swelling without stroke [Figure 2a and b].

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance features performed after decompressive craniotomy. (a) Axial fostering linkages in academic innovation and research weighted image, showing edema in left cerebral hemisphere. (b) Axial diffusion-weighted image without signs of ischemia, confirming brain swelling without stroke

The girl had good recovery, started on a rehabilitation program and after 6 months, she reached 4 points in Glasgow outcome scale, with a right hemiparesis grade 4 (worst score: 0; best score: 5) and no cognitive or language deficits.

Discussion

There is a high risk of morbidity and death among patients with unilateral hemispheric brain swelling following TBI who develop intractable intracranial hypertension. Despite advances in TBI care, the mortality rate remains high.[4] A few cases of hemispheric brain swelling have been described with long time lucid interval. Cerebral hypo perfusion, followed by hypoxia/ischemia and diffuse brain swelling are key points to understand the pathophysiology associated to delayed brain swelling.[5]

Several studies suggest that delayed diffuse brain edema after severe TBI may be more frequent in children than in adults.[6] However, the delayed onset of a malignant unilateral brain edema syndrome is very rare.[7] Although unusual, it highlights the importance of clinical and neurological observation of patients involved in high-impact trauma, especially children.

Primary cerebral damage occurs at the moment of impact and appears briefly after trauma. Secondary brain injury usually occurs several hours after trauma,[8] and plays a major role particularly in delayed deterioration. In rare conditions, it may appear after a couple of days after the trauma as presented in our case. Geddes et al.[9] demonstrated that the diffuse brain damage responsible for loss of consciousness is a hypoxic secondary reaction and not only diffuse axonal injury. One of the main conclusions of the study was that focal, localized axonal injury and secondary vascular-hypoxic changes characterize the mechanism of delayed brain deterioration.

Treatment with decompressive craniotomy is currently far more accurate in cases of unilateral brain swelling. Polin et al.[5] described trauma cases of various etiologies and patients with severe TBI who underwent decompressive craniectomy had favorable outcomes in 80% of cases, with statistical significance when compared with the control group. This report draws the attention to a rare and severe clinical condition that after decompressive craniectomy evolved with a good outcome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Paiva WS, Soares MS, Amorim RL, de Andrade AF, Matushita H, Teixeira MJ. Traumatic brain injury and shaken baby syndrome. Acta Med Port. 2011;24:805–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmarou A, Signoretti S, Fatouros PP, Portella G, Aygok GA, Bullock MR. Predominance of cellular edema in traumatic brain swelling in patients with severe head injuries. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:720–30. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.104.5.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donkin JJ, Vink R. Mechanisms of cerebral edema in traumatic brain injury: Therapeutic developments. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23:293–9. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328337f451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldrich EF, Eisenberg HM, Saydjari C, Luerssen TG, Foulkes MA, Jane JA, et al. Diffuse brain swelling in severely head-injured children. A report from the NIH Traumatic Coma Data Bank. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:450–4. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.3.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polin RS, Shaffrey ME, Bogaev CA, Tisdale N, Germanson T, Bocchicchio B, et al. Decompressive bifrontal craniectomy in the treatment of severe refractory posttraumatic cerebral edema. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:84–92. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199707000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett Colomer C, Solari Vergara F, Tapia Perez F, Miranda Vasquez F, Horlacher Kunstmann A, Parra Fierro G, et al. Delayed intracranial hypertension and cerebral edema in severe pediatric head injury: Risk factor analysis. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2012;48:205–9. doi: 10.1159/000343385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce DA, Alavi A, Bilaniuk L, Dolinskas C, Obrist W, Uzzell B. Diffuse cerebral swelling following head injuries in children: The syndrome of “malignant brain edema”. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:170–8. doi: 10.3171/jns.1981.54.2.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denton S, Mileusnic D. Delayed sudden death in an infant following an accidental fall: A case report with review of the literature. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2003;24:371–6. doi: 10.1097/01.paf.0000097851.18478.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geddes JF, Hackshaw AK, Vowles GH, Nickols CD, Whitwell HL. Neuropathology of inflicted head injury in children. I. Patterns of brain damage. Brain. 2001;124:1290–8. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.7.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]