Abstract

Context:

Early detection of predictors of adverse outcome will be helpful for neonatologists to plan management, follow up and rehabilitation in advance so that neurological disability can be minimised.

Aims:

The purpose of this study was to determine the factors affecting the adverse outcome of neonatal seizures.

Settings and Design:

This is a prospective study conducted in the neonatal unit of a tertiary care hospital. One hundred and eight newborns consecutively admitted with seizures were included in this study.

Materials and Methods:

Data was collected regarding perinatal history and seizure and evaluated for etiology. We conducted a retrospective analysis to identify the factors associated with adverse outcome after neonatal seizures.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Chi-square test with degree of freedom = 1 was used to find the variables significantly associated with adverse outcome (P < 0.05).

Results:

Gestational age, birth weight, Apgar score at 5 min, seizure onset <24 hrs, status epilepticus, radiological findings and EEG findings were significantly associated with outcome.

Conclusion:

Mortality and severe neurological impairment after neonatal seizure is associated with prematurity, LBW, low Apgar score at 5 min, etiologies like meningitis, sepsis, severe HIE, brain malformations, grade 3 or 4 IVH or intracranial haemorrhage, seizure onset <24 hours, presence of status epilepticus, severely abnormal radiological and EEG findings.

Keywords: Hypoxia-ischemia, neonatal seizures, new born, preterm infants, prognosis, seizures/diagnosis/etiology/mortality

Introduction

Neonatal seizure is a relatively common pediatric emergency and it is critical to determine the etiology and other factors that determine the outcome. Even with advanced perinatal care, mortality and morbidity of neonatal seizure remains high. There are a number of problems in diagnosis and management of neonatal seizures underscoring the dynamic nature of the study of neonatal seizures.[1]

Etiology is the most important factor reported to determine the outcome after neonatal seizures. Other than etiology, factors reported with adverse outcome are type of seizure, status epilepticus, early onset of seizures, gestational age, Apgar score, birth weight, need for resuscitation, neurological examination at onset of seizure, electroencephalogram (EEG) and radiological finding. Reliability of most of these factors is limited.[2]

The purpose of this study was to determine the factors affecting the adverse outcome of neonates admitted with seizures in neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). It is important to identify the early predictors of adverse outcome because it could be a valuable tool in providing advanced care and for an early referral for long-term follow-up and rehabilitation.

Materials and Methods

This is a prospective study undertaken in the tertiary care newborn unit. One hundred and eight newborns consecutively admitted with seizures unprovoked by stimulation, not abolished by restraint were included in the study. Those newborns who succumb to illness/death before investigations, babies who had poor or no documentation regarding perinatal events, neonates with jitteriness, tremor and benign sleep myoclonus were excluded. Evaluation included a thorough search for etiology, including detailed clinical history, maternal and perinatal risk factors. Data were collected regarding time of onset of seizure, type, duration and frequency of seizure, neurological examination at the onset of the seizure. Maternal and perinatal history including gestational age, type of delivery, birth weight, Apgar score at 1 and 5 min and need for and type of resuscitation at the time of birth were recorded. Routine chemistries, including blood sugar, sepsis screen, lumbar puncture, serum electrolytes such as sodium, calcium, magnesium, EEG, neuroimaging (ultrasonography/computerised tomography/magnetic resonance imaging [USG/CT/MRI]), TORCH screen and screen for inborn errors of metabolism were done wherever indicated. We followed-up the babies throughout the hospital stay till discharge/death and conducted a retrospective analysis to identify the variables that were significantly associated with adverse outcome. Association between the variables and outcome was analyzed by Chi-square test to find the statistical significance (degree of freedom = 1). The variables with P < 0.05 are considered to significantly affect the outcome after neonatal seizures.[2] For the statistical analysis resuscitation maneuvers were grouped into two categories: 1 (routine) = routine care/oxygen supplementation; and 2 (extra) = resuscitation >1 min with positive pressure ventilation+/endotracheal intubation+/cardiac massage+/drug therapy. Etiology was grouped into two categories: 1 (mild) = transient metabolic disorder, mild or moderate hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) of degree 1 or 2 or unknown etiology; 2 (moderate-severe) = severe HIE, IVH of degree 3 or 4, intracerebral hemorrhage, meningitis or sepsis. Multiple seizure types often coexisted in the same patient. Hence, patients were categorized as having one or multiple type of seizures. Status epilepticus was defined as seizure for 30 min or recurrent seizure that lasted for >30 min without definite return to baseline neurological condition between seizures. EEG was considered severely abnormal when there were asymmetries in the voltage or frequencies, low-voltage activity or a permanent discontinuous activity. USG/CT/MRI findings were considered severely abnormal when there was IVH of degree 3 or 4, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, periventricular hemorrhage or brain malformations. The outcome was categorized into two categories: 1 = favorable outcome, which included normal neurological examination, mild muscle tone+/reflex abnormalities; 2 = adverse outcome, which included death, severe neurological impairment.[2]

Results

Total number of cases admitted to NICU during the study period is 1956 among which 108 newborns had seizures (5.5%). There is a male preponderance in this study (55.5%) especially first born male babies are affected. Majority is preterm infants and small for date babies (58.3%). HIE (44.4%), alone (17.5%) or associated with other factors is the most common etiology. Second most common cause is sepsis (37.9%).

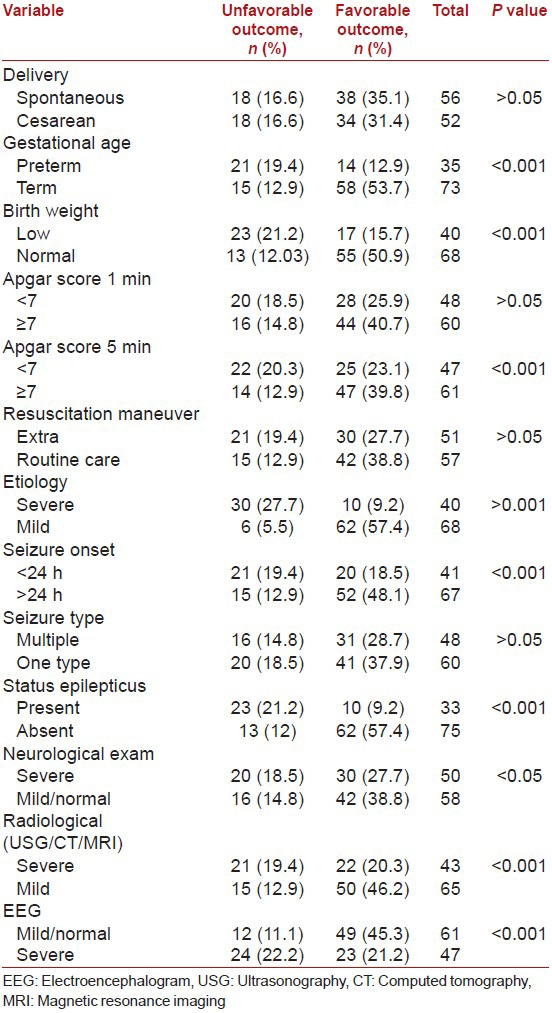

Outcome mortality in this study is 16 (17.2%) out of which 10 (62.5%) are males, and 6 (37.5%) are females. Severe neurological impairment is present in 20 (18.5%) cases and normal or mild neurological impairment in 72 (66.6%) cases [Table 1].

Table 1.

Association between variables and outcome

Discussion

Incidence of neonatal seizure in this study is 5.5%. Most of the cases were referred from peripheral hospitals. Hence, a true incidence based upon total live births cannot be calculated. Newborns with seizures are included based on clinical criteria without synchronized video EEG recording. Hence, newborns with very subtle or electrical only seizures might have been excluded.[3]

The reported incidence range from 0.5% to 22.2%. Hospital based studies including high risk cases show higher incidence of neonatal seizures than population study including infants in general nurseries and less ill. There is a male preponderance and majority were preterm infants and low birth weight babies in this study. Most of the studies show higher incidence in preterm babies.[4,5,6] Most common etiology reported still remains HIE and sepsis in this era of advanced perinatal care.[1] Mortality in the present study is 17.2% and reported in literature is 9-15%.[7] It is important for the neonatologists to have early and accurate predictors of outcome to plan the management. The variables selected in this study are easily available including the instrumental investigations.

Birth weight, gestational age, Apgar score at 5 min, etiology, seizure onset <24 h, status epilepticus, severe EEG and radiological (USG/CT) abnormality are found significantly associated with adverse outcome in this study. Prognostic factors reported in literature are etiology, seizure type, early onset of seizure, prolonged and recurrent seizure, gestational age, birth weight, Apgar score at 5 min, need for resuscitation maneuvers, neurological examination, EEG, and USG findings.[2,8,9] Mode of delivery, Apgar at 1 min, resuscitation maneuver, seizure type, neurological examination at onset of seizure are not found significantly associated with adverse outcome in this study. Some studies report that newborns with generalized tonic, myoclonic and subtle seizures have poor outcome compared with those with clonic seizures but recent studies report that prognostic significance of seizure type is not reliable as multiple seizure type often coexist in same patient.[2] Apgar score at 5 min than at 1 min is described as reliable predictor of neurological outcome.[10,11] Need for resuscitation correlates with Apgar at 1 min both of which are found not significantly associated with adverse outcome in the present study. Preictal neurological examination is described significantly associated with outcome. In this study, we have analyzed only the neurological examination after the onset of seizure, which is found not significantly associated with outcome. Neonatal status epilepticus, which is most often of symptomatic origin with extensive structural brain injury is likely to have significant influence on outcome than prolonged or recurrent seizure, which is often associated with favorable prognostic factors like hypocalcemia.[2]

The inclusion of newborn with seizures was based on clinical criteria without synchronized video EEG recording. This might have resulted in inclusion of newborns with seizure mimics which have different prognosis. Recurrent seizure thought to be associated with adverse outcome was not included. Accurate seizure duration determination is a time consuming process and it requires a systematic data collection of the duration of each seizure episode. MRI, which is a helpful tool in determining periventricular white matter lesions, is not done in majority of cases due to financial constraints in this study. It has inherent difficulties in patient preparation, safety, and timing.[2] This study includes short-term follow-up only; further follow-up is required to evaluate long-term neurological follow-up.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Tekgul H, Gauvreau K, Soul J, Murphy L, Robertson R, Stewart J, et al. The current etiologic profile and neurodevelopmental outcome of seizures in term newborn infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1270–80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pisani F, Sisti L, Seri S. A scoring system for early prognostic assessment after neonatal seizures. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e580–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah DK, Boylan GB, Rennie JM. Monitoring of seizures in the newborn. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97:F65–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.169508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ronen GM, Penney S, Andrews W. The epidemiology of clinical neonatal seizures in Newfoundland: A population-based study. J Pediatr. 1999;134:71–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saliba RM, Annegers FJ, Waller DK, Tyson JE, Mizrahi EM. Risk factors for neonatal seizures: A population-based study, Harris County, Texas, 1992-1994. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:14–20. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glass HC, Pham TN, Danielsen B, Towner D, Glidden D, Wu YW. Antenatal and intrapartum risk factors for seizures in term newborns: A population-based study, California 1998-2002. J Pediatr. 2009;154:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.07.008. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ronen GM, Buckley D, Penney S, Streiner DL. Long-term prognosis in children with neonatal seizures: A population-based study. Neurology. 2007;69:1816–22. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000279335.85797.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pisani F, Leali L, Parmigiani S, Squarcia A, Tanzi S, Volante E, et al. Neonatal seizures in preterm infants: Clinical outcome and relationship with subsequent epilepsy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;16(Suppl 2):51–3. doi: 10.1080/14767050410001727215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garfinkle J, Shevell MI. Prognostic factors and development of a scoring system for outcome of neonatal seizures in term infants. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2011;15:222–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garfinkle J, Shevell MI. Predictors of outcome in term infants with neonatal seizures subsequent to intrapartum asphyxia. J Child Neurol. 2011;26:453–9. doi: 10.1177/0883073810382907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebremariam A, Gutema Y, Leuel A, Fekadu H. Early-onset neonatal seizures: Types, risk factors and short-term outcome. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2006;26:127–31. doi: 10.1179/146532806X107476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]