Abstract

Context:

There is a paucity of data evaluating serum albumin levels and outcome of critically ill-children admitted to intensive care unit (ICU).

Aims:

The aim was to study frequency of hypoalbuminemia and examine association between hypoalbuminemia and outcome in critically ill-children.

Settings and Design:

Retrospective review of medical records of 435 patients admitted to 12 bedded pediatric ICU (PICU).

Materials and Methods:

Patients with hypoalbuminemia on admission or any time during PICU stay were compared with normoalbuminemic patients for demographic and clinical profile. Effect of albumin infusion was also examined. Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval were calculated using SPSS 16.

Results:

Hypoalbuminemia was present on admission in 21% (92 of 435) patients that increased to 34% at the end of 1st week and to 37% (164 of 435) during rest of the stay in PICU. Hypoalbuminemic patients had higher Pediatric Risk of Mortality scores (12.9 vs. 7.5, P < 0.001) and prolonged PICU stay (13.8 vs. 6.7 days, P < 0.001); higher likelihood of respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilaton (84.8% vs. 28.8%, P < 0.001), prolonged ventilatory support, progression to multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (87.8% vs. 16.2%) and risk of mortality (25.6% vs. 17.7%). Though, the survivors among recipients of albumin infusion had significantly higher increase in serum albumin level (0.76 g/dL, standard deviation [SD] 0.54) compared with nonsurvivors (0.46 g/dL, SD 0.44; P = 0.016), albumin infusion did not reduce the risk of mortality.

Conclusions:

Hypoalbuminemia is a significant indicator of mortality and morbidity in critically sick children. More studies are needed to define role of albumin infusion in treatment of such patients.

Keywords: Critically sick children, hypoalbuminemia, pediatric intensive care unit

Introduction

Albumin is a highly water soluble protein, one-third of which is distributed in the intravascular space and two-third in the extravascular space. It constitutes up to two-third of total plasma protein, contributing about 80% of the plasma colloid osmotic pressure and is responsible for the transport and binding of many molecules.[1] Hypoalbuminemia is a frequent and early biochemical derangement in critically ill-patients.[2] The etiology of hypoalbuminemia is complex. In general, it is ascribed to diminished synthesis in malnutrition, malabsorption and hepatic dysfunction or increased losses in nephropathy or protein-losing enteropathy. Inflammatory disorders can accelerate the catabolism of albumin, while simultaneously decreasing its production. Diversion of synthetic capacity to other proteins (acute-phase reactants) is another likely cause of hypoalbuminemia in critically ill-patients.[3,4] During critical illness, capillary permeability increases dramatically and alters albumin exchange between intravascular and extravascular compartments.[5] Hypoalbuminemia in this setting in adult patients is a marker of disease severity and has been associated with prolonged ventilatory dependence and length of intensive care stay.[6] It is also an independent predictor of mortality and it is associated with poor outcome in critically ill-adults.[2,7,8,9] There is a paucity of data evaluating serum albumin levels and outcome of critically ill-children admitted to intensive care unit (ICU).[4,10] The objective of this study was to evaluate frequency of hypoalbuminemia in critically sick children admitted to pediatric ICU (PICU) and examine association between hypoalbuminemia and the outcome of illness.

Materials and Methods

Patient inclusion

We performed retrospective review of medical records of data of all patients admitted to our 12 bed PICU at tertiary care teaching hospital in India between 1st January 2008 and 31st December 2008. All patients admitted to PICU were potential subjects. The need for approval from the Institute's Ethics Review Committee was waived for this retrospective analysis. It is the unit's policy to perform comprehensive metabolic profile including serum albumin level of all admitted patients at the time of admission and twice weekly thereafter. Hypoalbuminemia was defined as an albumin level of less than 2.5 g/dL at any time during PICU stay. Serum albumin level done within first 48 h of admission was considered as admission albumin level. Albumin infusion in sick children in the dose of 2 g/kg was common practice when the study was performed however cost constrains precluded this practice and few patients were not able to receive sufficient amount of human serum albumin.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who were expected to have a low albumin level in their usual state of health were excluded. Therefore children with known immune deficiency, malabsorption syndrome, celiac disease, protein loosing enteropathy, nephrotic syndrome, and chronic liver disease were excluded from the study.

Data retrieved from case records included demographic profile (age, sex, and weight); disease severity (Pediatric Risk of Mortality [PRISM] score); primary system involvement (neurologic, respiratory, cardiac, hematologic and generalized sepsis without specific organ system involvement); albumin level and hypoalbuminemia at admission and thereafter; length of PICU stay; length of ventilatory support; occurrence of multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS); number of organ failures and final outcome (death or survival). MODS was defined as “the presence of altered organ functions in an acutely ill-patient such that homeostasis cannot be maintained without intervention”.[11]

Data analysis

For parametric data comparisons were done using Pearson Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. For nonparametric data, Mann-Whitney U-test was performed. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were estimated using SPSS for Windows, Version 16.0. Chicago, SPSS Inc.

Results

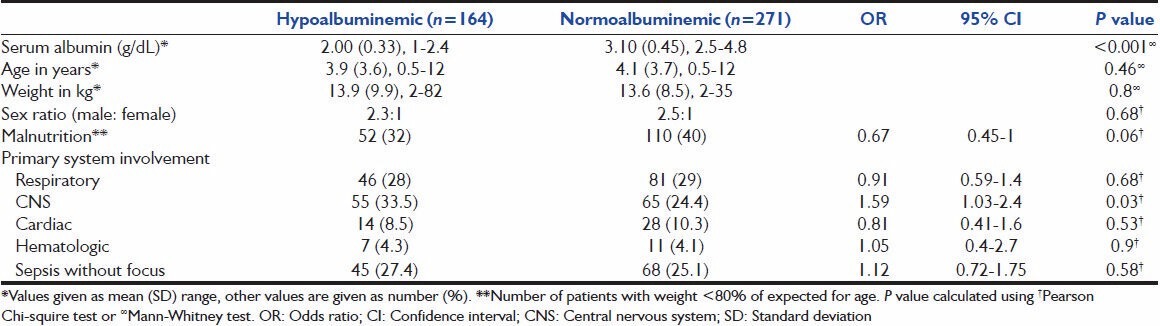

The medical records of 435 patients were reviewed after excluding data of four patients with nephrotic syndrome. Hypoalbuminemia was present on admission in 21% (92 of 435) patients, which increased to 34% (151 of 435) patients at the end of 1st week and to 37% (164 of 435) during rest of the stay in PICU. Mean albumin level of studied population was 2.61 g/dL (standard deviation [SD] 0.67); 2.00 g/dL (SD 0.33) in hypoalbuminemic group, while 3.1 g/dL (SD 0.45) in normoalbuminemia group (P < 0.001). Mean age, weight and sex ratio in both groups was matched, but entire population had male predominance (male:female ratio 2.44:1) [Table 1]. In hypoalbuminemic group average weight was 13.9 kg (87% of expected for age 3.9 years), while in normoalbuminemic group average weight was 13.6 kg (82% of expected for age 4.1 years). Both the groups were statistically matched. Of 435 patients, 162 (37%) had malnutrition (weight below 80% of expected for their age) with similar distribution in hypoalbuminemic and normoalbuminemic groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and diagnosis of patients with respect to albumin levels

The diagnostic categories of the patients are given in Table 1. The odds of presence of central nervous system (CNS) infection (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.03-2.4; P = 0.03) was higher in hypoalbuminemia group. The differences between the groups with respect to other diagnoses were not significant.

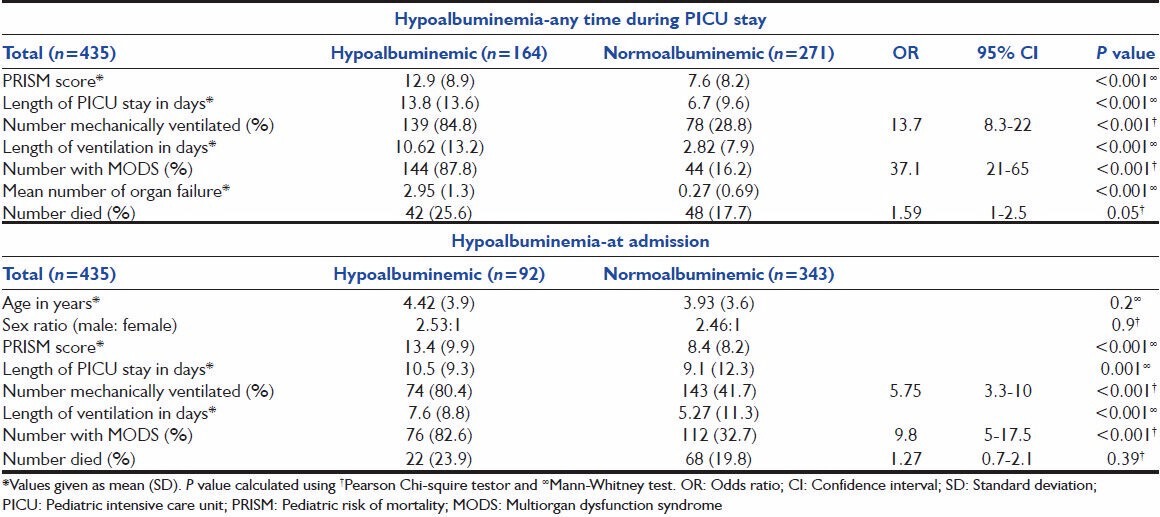

Hypoalbuminemic patients had higher PRISM scores (12.9 vs. 7.5, P < 0.001) and prolonged PICU stay; higher likelihood of respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilator (84.8% vs. 28.8%, OR 13.7, 95% CI 8.3-22.6, P < 0.001), prolonged ventilatory support and progression to MODS (87.8% vs. 16.2%, OR 37.1, 95% CI 21-65, P < 0.001). The hypoalbuminemia group had a higher mean number of organ failures compared with those in the normal albumin level group (2.95 SD 1.3 vs. 0.27 SD 0.69; P < 0.001) and risk of mortality (25.6% vs. 17.7%, OR 1.59, 95% CI 1-2.55, P = 0.05) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Outcome of patients with respect to presence of hypoalbuminemia

Similar comparisons were done between patients with hypoalbuminemia on admission and those with normal albumin level. Patients with hypoalbuminemia on admission had higher PRISM scores (13.4 vs. 8.4, P < 0.001), prolonged PICU stay, higher odds of assisted respiratory support in the form of mechanical ventilation (80.4 vs. 41.7%, OR 5.75, 95% CI 3.3-10, P < 0.001) and progression to MODS (82.6 vs. 32.7%, OR 9.8, 95% CI 5-17.5, P < 0.001). Although mortality rate was higher in hypoalbuminemia group (23.9 vs. 19.8%), but it was statistically not significant.

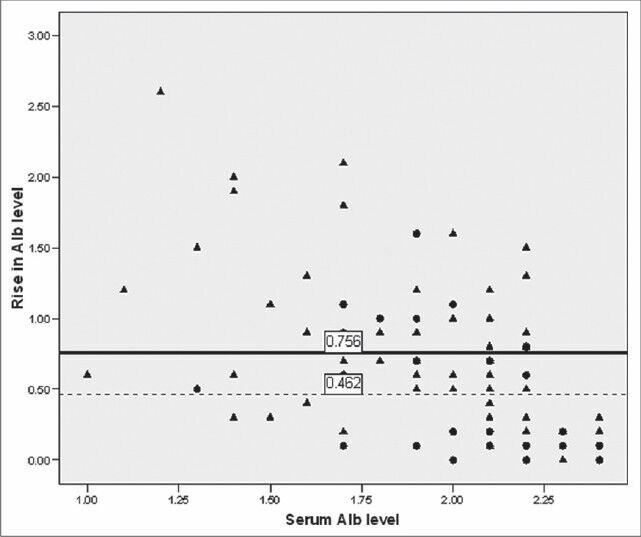

Patients who received albumin infusion had more severe diseases (mean PRISM 15; SD 7.0 vs. 12.1; SD 9.6, P = 0.03) and prolonged hospital stay (16.6 days; SD 12.4 vs. 11.5 days; SD 14, P = 0.02). Albumin infusion corrected hypoalbuminemia in 54 of 72 (75%) patients while fresh frozen plasma did so in 7 of 20 (35%) patients. There was no difference in outcome between albumin recipients and others (OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.39-1.6, P = 0.06) however, average increase in serum albumin level was significantly lower in patients who died in comparison to those who survived (0.46 g/dL; SD 0.44 vs. 0.76 g/dL; SD 0.54; P = 0.01) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Outcome of patients with respect to average rise in serum albumin level after albumin infusion and baseline albumin level. Solid circle (●) indicates death, triangle (▴) indicates survivors, solid line (-) shows mean increase in serum albumin level among survivors and dotted line (---) among patients who died

Discussion

We found hypoalbuminemia in about one-third of patients, which is consistent with data of Horowitz and Tai.[4] Mean serum albumin in our study population (2.61 g/dL, SD 0.67) is lower than similar pediatric studies.[4,10] The cause could be high incidence of malnutrition in our population; 37% of children included in the study had weight below 80% of expected for their age. However, the occurrence of hypoalbuminemia in our patients may not be related to nutritional status, as the distribution of children with malnutrition (derived as weight for age < 80% of expected) was similar in two groups. Probably, the stress of critical illness and sepsis were the reasons for hypoalbuminemia. In critically ill and with severe sepsis the metabolic reaction modifies to create great amounts of acute phase proteins. Since albumin is not an acute phase protein, diversion of synthetic capacity to other proteins is likely to reduce albumin synthesis.[8,12,13] Other probable reason suggested in causation of hypoalbuminemia in such patients is enhanced vascular permeability, which would encourage a larger shift of albumin from the vascular to the interstitial space.[3,8,14] Half-life of albumin being about 2 weeks, delayed presentation could be contributory to high PRISM score and low serum albumin in hypoalbuminemia group though we do not have reliable information on duration of illness prior to hospitalization in this retrospective data collection. Male predominance in admissions to pediatric emergency in poisoning and accident cases is well reported in India and has varying underlying reasons.[15] Male predominance in children admitted to PICU probably has similar reasons.

Murray et al. established that serum albumin level was associated with longer ICU and hospital stay in sick patients.[16] Furthermore in the adult trauma population, patients with a lower serum albumin level (<2.6 g/dL) were found to have significantly longer ICU and hospital lengths of stay, prolonged ventilatory support and greater mortality when matched for age and injury severity.[2] In our study, hypoalbuminemic patients had prolonged PICU stay, high incidence of respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilator, prolonged ventilatory support, and higher mean number of organ failure. These results are largely consistent with findings by Horowitz and Tai[4] and Durward et al.[10] The study by Durward et al. measuring anion gap in hypoalbuminemic children, however, did not find hypoalbuminemia as an independent predictor of mortality; mean albumin levels were similar between survivors and nonsurvivors.[10] However, other investigators found that, in medical and surgical patients, serum albumin level had low sensitivity and specificity for predicting hospital mortality.[17] Distinct from the previous studies we also found higher odds of CNS involvement and progression to MODS in hypoalbuminemic group. Though we could not find direct reports relating hypoalbuminemia to CNS infections, low serum albumin is well reported marker of poor prognosis in ischemic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage and traumatic brain injury.[18,19] It exerts neuroprotective effect in CNS insults by different mechanisms like improving cerebral perfusion through oncotic effect, binding and inactivation of toxic products, maintenance of microvascular permeability to proteins and scavenging of free radicals and prevention of lipid peroxidation.[19] In hypoalbuminemia group, deficient neuroprotection could be indirectly related to higher odds of CNS involvement.

Whatever the cause of low albumin levels, the decreased plasma colloid osmotic pressure is likely to compromise the intravascular volume, placing the child at risk for inadequate blood flow to vital organs. This is especially true of capillary leak, in which the albumin escapes to the interstitial space, pulling fluid along. Albumin infusion should therefore, improve the outcome of hypoalbuminemia patients. The use of albumin infusion as a treatment for hypoalbuminemia however, remains a subject of ongoing debate and several evidenced-based reviews.[3,8,20] In SAFE study, use of albumin replacement as a volume expander for the critically ill-adults with hypotension did not result in decreased mortality or morbidity.[20] In our study, the results were similar. Probable reason for absence of significant difference in outcome of albumin recipient and nonrecipients seems to be higher disease severity and prolonged length of hospital stay in the former group. However, average rise in serum albumin level was significantly lower in nonsurvivors compared with survivors after albumin infusion. It is possible that nonsurvivors did not receive the adequate amount of albumin infusion. There is no much data in pediatric population, however a randomized, controlled, pilot study in adults concludes that albumin administration improves organ function in critically ill hypoalbuminemia patients.[21] Our study suffers the limitations of retrospective analysis. Further prospective randomized trials with targeted rise in serum albumin level might be helpful in resolving the issue.

In summary, we found that hypoalbuminemia is common in patients admitted to our PICU. It was a significant indicator of mortality and morbidity, which is agreement of limited published data in adults and children. Replacement of albumin is very likely to improve serum albumin level, but may not reduce the risk of mortality.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.McPherson RA, Pincus MR. Specific protiens. In: McPherson RA, Pincus MR, editors. Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. 21st ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. pp. 511–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung J, Bochicchio GV, Joshi M, Bochicchio K, Costas A, Tracy K, et al. Admission serum albumin is predicitve of outcome in critically ill trauma patients. Am Surg. 2004;70:1099–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson JP, Wolmarans MR, Park GR. The role of albumin in critical illness. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:599–610. doi: 10.1093/bja/85.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horowitz IN, Tai K. Hypoalbuminemia in critically ill children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:1048–52. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleck A, Raines G, Hawker F, Trotter J, Wallace PI, Ledingham IM, et al. Increased vascular permeability: A major cause of hypoalbuminaemia in disease and injury. Lancet. 1985;1:781–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91447-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rady MY, Ryan T. Perioperative predictors of extubation failure and the effect on clinical outcome after cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:340–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199902000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldwasser P, Feldman J. Association of serum albumin and mortality risk. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:693–703. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent JL, Dubois MJ, Navickis RJ, Wilkes MM. Hypoalbuminemia in acute illness: Is there a rationale for intervention. A meta-analysis of cohort studies and controlled trials? Ann Surg. 2003;237:319–34. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000055547.93484.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, McNair DS, Malila FM. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: Hospital mortality assessment for today's critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1297–310. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000215112.84523.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durward A, Mayer A, Skellett S, Taylor D, Hanna S, Tibby SM, et al. Hypoalbuminaemia in critically ill children: Incidence, prognosis, and influence on the anion gap. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:419–22. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.5.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cengiz O, Kocer B, Sürmeli S, Santicky MJ, Soran A. Are pretreatment serum albumin and cholesterol levels prognostic tools in patients with colorectal carcinoma? Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:CR240–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doweiko JP, Nompleggi DJ. The role of albumin in human physiology and pathophysiology, Part III: Albumin and disease states. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1991;15:476–83. doi: 10.1177/0148607191015004476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodoman GV, Shalaeva TI, Dobretsov GE, Naumov EK, Obolenskii VN. Serum albumin in systemic inflammatory reaction syndrome. Anesteziol Reanimatol. 2006;2:62–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohli U, Kuttiat VS, Lodha R, Kabra SK. Profile of childhood poisoning at a tertiary care centre in North India. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75:791–4. doi: 10.1007/s12098-008-0105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray MJ, Marsh HM, Wochos DN, Moxness KE, Offord KP, Callaway CW. Nutritional assessment of intensive-care unit patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63:1106–15. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65505-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yap FH, Joynt GM, Buckley TA, Wong EL. Association of serum albumin concentration and mortality risk in critically ill patients. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2002;30:202–7. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0203000213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee YW, Ahn JY, Han IB, Chung YS, Chung SS, Kim NK. The influence of hypoalbuminemia on neurological outcome in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Korean J Cerebrovasc Surg. 2005;7:109–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abubakar S, Sabir A, Ndakotsu M, Imam M, Tasiu M. Low admission serum albumin as prognostic determinant of 30-day case fatality and adverse functional outcome following acute ischemic stroke. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14:53. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.14.53.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finfer S, Bellomo R, Boyce N, French J, Myburgh J, Norton R, et al. A comparison of albumin and saline for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2247–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubois MJ, Orellana-Jimenez C, Melot C, De Backer D, Berre J, Leeman M, et al. Albumin administration improves organ function in critically ill hypoalbuminemic patients: A prospective, randomized, controlled, pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2536–40. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239119.57544.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]