Abstract

Despite the impressive growth of the Indian economy over the past decades, the country struggles to deal with multiple and overlapping forms of inequality. One of the Indian government's main policy responses to this situation has been an increasing engagement with the ‘rights regime’, witnessed by the formulation of a plethora of rights-based laws as policy instruments. Important among these are the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM). Grounded in ethnographic research in Rajasthan focused on the management of maternal and child health under NRHM, this paper demonstrates how women, as mothers and health workers, organise themselves in relation to rights and identities. I argue that the rights of citizenship are not solely contingent upon the existence of legally guaranteed rights but also significantly on the social conditions that make their effective exercise possible. This implies that while citizenship is in one sense a membership status that entails a package of rights, duties, and obligations as well as equality, justice, and autonomy, its development and nature can only be understood through a careful consideration and analysis of contextually specific social conditions.

Keywords: Rajasthan, NRHM, rights, citizenship, community health workers

Introduction

The Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) in a small village in Alwar, in Rajasthan state, walks from house to house and reminds mothers to come to the Anganwadi Centre for Mother and Child Health Nutrition (MCHN) day, a recurring outreach session. Usually, she is called in for a cup of tea when approaching the gate. In some instances, she accepts the invitation to sit down and take part in small talk and village gossip. Upon leaving, she enquires about the health of the children in the household and urges them to come to participate in the approaching MCHN day. She reminds them to bring the Mother and Child Protection Card (MCPC). In several houses, she does not answer to the gesture of hospitality offered but politely refuses, as her time is limited and the houses she has to approach are many. She calls the mother to come to the gate and bring her children and the MCPC. She takes a quick look at the card and orders the mother to bring the child for the scheduled immunisation. Although several children are playing in the courtyard, there are a few houses where she does not stop at all. Upon an enquiry, she explains that there is no reason to; there are far too many children in these households to bother.

The preferences of the ASHA as she makes a round to inform households of the upcoming health day are not accidental. In rural Alwar, class, caste and gender structure people's daily lives. Caste and class are fundamental characteristics of social organisation in Alwar influencing the position and status of women in complex ways.

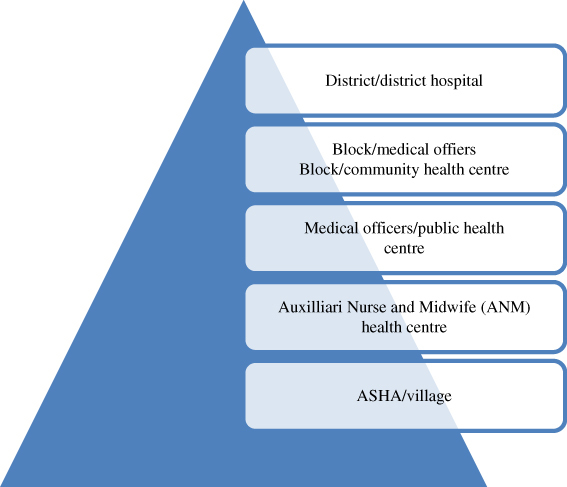

Alwar is one of the Rajasthan's 33 districts and reckoned as one of the state's poorest districts. Of Rajasthan's 68.5 million people, over 674,000 reside in Alwar (Census, 2011). Although the city of Alwar of late has become an industrial hub, farming and agriculture account for the main source of income for most households. According to a baseline survey on child and related maternal health care, there is a low literacy rate for women in Alwar and challenging maternal and child health indicators. A declining child sex ratio is further indicative of a strong preference for sons. Most households are Hindu, Muslims being the largest minority. Approximately, 8% of the total population belong to the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. A sizeable proportion of households (43.9%) come from the Other Backward Caste (OBC) (Ghosh, 2009). Historically, the OBC consist of disadvantaged groups given certain preferences for health, education and employment. Only a very small proportion of households are covered under a health insurance scheme (6.9%). The ASHA, the community health mobiliser, is responsible for increasing utilisation of the public health system. In Alwar, the public health structure consists of 24 community health centres, 70 public health centres and one district hospital (Ghosh, 2009; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Health system hierarchy.

Markers of social distinction form aspects of relations in this extremely heterogeneous society. All households approached by the ASHA are marked by the designation below the poverty line (BPL) household (households living BPL), a status that positions them as beneficiaries, or as a specifically targeted group for state health programmes. Caste and class may not be actively politicised, but are far from being inactive in these encounters. The ASHA, herself a Brahmin, the caste of highest ranking in Hindu India, remains at the gate when visiting households of the scheduled caste or Muslims. Households not conforming to the ‘two-child norm’ are looked upon as households of non-compliant citizens and hence not approached at all.

The theme of this paper is the incomplete and paradoxical project of neo-liberal health system reform in India. Neo-liberal ideology divides the population into those who are responsible, productive and able to manage their affairs on their own and those who are dependent and need to rely on state welfare (Fraser & Bedford, 2008, p. 228). Citizenship in this neoliberal context means to be autonomous and competent. Public health interventions are thus geared towards changing individual behaviour so that women can manage to take care of themselves and their children.

The policy landscape of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in India, as health system reform, has a strong focus on the health needs of women as mothers and their children. In this paper, I am particularly concerned with the dimension of gendered citizenship of this health system reform and the paradoxical claims made to women. On the one hand, there is a call to poor women to become active participating citizens with rights and a strong voice to claim them. The NRHM attempts at renewal and reform in making use of women's agency, both as health workers and as mothers. On the other hand, there are equally strong claims to women to comply and buy into the health projects as they are crafted in governmental policies. Within this governmental endeavour, women juggle the tension of being seen as both passive and active citizens; both the objects and the agents reform.

My ethnographic focus is on the relationships between expectant mothers and ASHAs – the community health workers that have become the Government of India's most prominent tools under the NRHM. This paper is based on fieldwork conducted by the author at intervals during the period 2009–2013, as principle researcher of three large research projects. The focus of these three studies has been on the policies and practises of health system reform. My individual attention within these larger interdisciplinary projects has been on the practise of state health interventions, particularly the community health workers as a distinct site where the state and state practises are materialised, interpreted and understood. By virtue of being a first-liner, the ASHA can be perceived as constituting the boundary of the state in relation to its citizenry. I have participated and observed ASHAs in their training, followed a group of trained ASHA into their individual communities and taken part in the work and everyday challenges. I have conducted numerous open-ended in-depth interviews as well as participated in several focus group discussions conducted by members of the research teams with ASHA, other health staff, village women and their families 1 . I argue that in the state's attempt to engage with poor, marginalised rural women, the encounter between mothers and health workers constitutes both the state and these women's affiliation to it (see Mishra, this volume). The focus upon expectant mothers and health workers, therefore, provides a means to explore the ways citizenship in neo-liberal reform is enacted, how women citizens organise themselves for rights and identities, and how they exercise their agency in its pursuit. I ask what kind of state is visualised and what kind of female citizenry is imagined as its responsible partner, and in turn how women imagine themselves as citizens. This perspective highlights the social and political tensions, paradoxes and challenges of health system reform articulated in the shifts in policies from welfare to a rights regime.

Before turning to these questions, I will first give a short account of the shift in Indian development policy from development as a government welfare activity to recognition of basic development needs as a right, and how this shift implies new techniques of governance, centred crucially on this notion of ‘the citizen’.

Neo-liberal reform and citizenship

With the impressive growth of the Indian economy over the past two decades, the country has made significant advances in the field of human development. Life expectancy and literacy rates have increased, poverty levels have declined and large-scale famines have all but disappeared. On the global scene, India increasingly appears as an assertive nation taking long economic strides to attract unprecedented levels of domestic and foreign direct investment (Kaur, 2012, p. 604), buoyed by a vast and prosperous middle class that is conventionally seen as proponents of the country's embrace of economic liberalisation and globalisation (Fernandes & Heller, 2008). Nevertheless, 400 million Indians continue to live BPL, and chronic hunger and malnutrition remain widespread (Banik, 2011). Major disparities exist between urban and rural areas, regions, social groups and between men and women. Thus, while some western and southern states have regularly touched double-digit growth rates, many states in the north have continued to lag behind on most development indicators (Andersen, 2011, p. 270). While India's engagement with economic liberalisation and restructuring thus creates prosperity in the aggregate, it similarly presents the country with the continuous challenges of how to deal with multiple and overlapping forms of inequality and exclusion – spatial, social, economic and gendered.

In their recent book, An Uncertain Glory: India and its Contradictions (2013), Drèze and Sen call for a public welfare system that works better for the millions of people living in destitution. They question the pitiable investments in health and education made by the Indian government and ask what difference it makes to lift millions above some notional poverty line if they still lack the basics for a decent life. Similarly, Gupta questions why has a state ‘whose proclaimed motive is development failed to help the large number of people who still live in dire poverty?’ (Gupta, 2012, p. 3). Gupta suggests that the technocratic use of statistics, a de-politicised form of technocratic governance, removes the suffering of millions of people from public sight. In a similar vein, Drèze and Sen argue that the poor and the conditions of the poor lack political space in the public discourse (Drèze & Sen, 2013). Bangladesh, similar to India in many ways, has recently been celebrated as an exceptional health performer (Chowdhury et al., 2013). Sen (2013) notes that radical civil movements enhancing the power of women and women's active political role in society and the economy have been important factors behind this success in Bangladesh. Since liberation, there has been a political emphasis on empowering women, on removal of female disadvantage and unlocking the power of women's active role in society to reform both health care and education (Sen, 2013).

Over the past decade, the Indian government's policy response to prevailing inequality has been an increasing engagement with the rights regime, and the responsibility of the individual to claim these rights, evidenced by the formulation of a plethora of rights-based laws as policy instruments. Simultaneously, however, neo-liberal ideas and reform have extensively spread across many types of welfare and development regimes and policy sectors. The success of this ideological discourse, particularly during the past decade, is largely due to the message that it conveys around efficiency, accountability and equity (Corbridge, Williams, Srivastada, & Véron, 2005; Gupta & Sharma, 2006). The NRHM is important amongst these, focusing on health and human-resource development in rural areas. NRHM is one important manifestation of the new techniques of governance, centred crucially on this notion of ‘the citizen’, and epitomises the broader shift in Indian development policy from a perception of development as a welfare activity of the government, to recognition of basic development as a right of citizens (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], 2010, pp. 5–8). The guiding idea underlying this shift is the conviction that laws enabling citizens to assert their rights compel government performance and reform (UNDP, 2010, p. 52). India's current health policy is thus not simply economically ameliorative; it also seeks to create aware and active citizens out of rural poor and marginalised groups through new technologies of governance. Yet there is a continuous tension between policies as formulated and policies as practised, between neo-liberal and welfare ideas and between participation and compliance. On the one hand, the NRHM seeks to guarantee governmental responsibility for an acceptable level of welfare to all citizens. On the other hand, its achievement is sought through a focus on the individual responsibility of mothers and health workers to comply and participate in the state health programme.

Foucault (2007, 1991) has alerted us to how individuals, under neo-liberal regimes, are taught to govern themselves. Neo-liberal health reforms direct attention towards changing individuals and individual behaviours. Human rights have, under neo-liberal reform, become a global standard or norm with reference to which states, health systems, health workers, communities, families and mothers may be evaluated and disciplined. But it is with respect to these same human rights norms that individuals increasingly also evaluate themselves, and change their behaviour in order to conform (at least officially) to the norm. This form of power creates a set of rules and standards that result from a constellation of discursive structures, and the (scientific) knowledge and practices that accompany them. Power in this sense is positive, as it produces behaviour that is in conformity with the dominant standard of normality or acceptability mediated by a dominant view of what constitutes normality or deviance. Explicitly, Foucault draws our attention to how neo-liberalism as a political rationality induces dynamics of de-politisation of the public health regime, thus transforming political actors into clients, consumers and technologists of themselves (1991, 1997). Arguably, the NRHM is also a reaction against the neoliberal regime, of privatisation and inequality in access, and could be interpreted as a defence of the public health system and the responsibility of the state to ease the suffering of the poor. Defined by statistical measures, the designation BPL establishes the identity of the poor and those considered by the state as entitled to public services. The BPL designation and the provision of public services are also instrumental forms of the politics of forming poor (passive) subjects into what the state considers active participating citizens (Roalkvam, 2012, p. 249).

Although the rights regime can individualise and de-politicise social struggle, the language of rights are also frequently used for mobilisation and structural change. We need then to explore, I argue, how disciplinary power can provoke counter tendencies, exercised within historically and geographically contingent forms. Foucault gives us less nuanced ways to understand these contradictions that are, as I will demonstrate, fed by efforts of mobilisation and self-organisation that may both sustain, enhance or oppose state efforts. These mixed reactions and their implications require long-term, close, and even tedious scrutiny – often at the everyday, mundane and grassroots levels – to ultimately unravel the spatial and institutionally entrenched neo-liberal doctrine's promises of progress, freedom and reform. The NRHM has a particular focus upon the health of poor women and their children. The poor mother and her children matters to the state, yet this promise of freedom, progress and reform demands a form of model citizenship as its counterpart.

State benevolence and model citizens

With its large population, India accounts for a sizeable proportion of global mortality, with an estimated 68,000 maternal deaths and 1.5 million deaths among children under five every year (Paul, Mohapatra, & Kar, 2011). At present, the World Bank (2013) estimates India's maternal mortality ratio to be 200 deaths per 100,000 live births. The more pertinent statistic concerns the poorest segment of the population. The NRHM is a specific-purpose grant funded and planned by central government to induce health system reform in the individual states to address these challenging health indicators. The efforts of NRHM can be seen as a token of the benevolent welfare state, indicative of Gupta's arguments that the Indian state ‘far (…) from being indifferent to the plight of the poor display(ed) great care for a segment of its population’ (Gupta, 2012, p. 13). The NRHM is a revitalisation of the Primary Health Care Principles and underscores values such as equity and social justice (Bhatia & Rifkin, 2010, p. 2). It is not simply health services, important as these are, but also a system that is participatory and democratic that can act upon the underlying social, economic and political causes of ill health. NRHM has thus, and rightly so, been analysed as, in part, a product of changing global norms and discourses centred on human rights and dignity that make it unacceptable for governments to leave entire population groups in poverty without any means of subsistence (Chatterjee, 2008, p. 55; Roalkvam, 2012; Roalkvam, McNeill, & Blume, 2013).

Within the new Indian state, citizenship is being constructed, invoked and substantiated as ways to soften – if not eliminate – gender, class and caste inequalities. Indeed, as the early scholars of citizenship suggested, at the core of the concept of citizenship lies the contradiction between formal political equality and extensive social and political inequality (Marshall, 1977; Turner, 1990, p. 191). The joint family with its caste, kin and gender hierarchies – the state's counterpart in this endeavour – is seen as too authoritarian to form the basis for a democratic state (Devanandan & Thomas, 1966; Hodges, 2004). Since Indian independence, social reforms have referred to the nuclear family as the new foundation for the developing state. To the modern state, traditional large family structures are a hindrance to political democracy, development and social justice, all of which have been and still are India's national goals. Citizenship thus does not refer only to formal inequality but also to how citizens should behave to move forward and/or upward and become full citizens of the polity.

In social policies, the ideal citizen is portrayed in government family planning and health campaigns (since the early 1970s) with slogans such as ‘Ham do, hamare do’ (We two, our two), with an image of an inverted red triangle framing the family of mother, father and child (Nordfeldt & Roalkvam, 2010; Mishra & Roalkvam, 2014). NRHM's official government logo portrays a nuclear family (i.e. a family group consisting of a pair of adults – a woman and man), and although the nuclear family can have many children, the NRHM logo portrays a couple with only one child. The two-child norm introduced in some states of India through the Panchayat Raj institutions in the 1990s clearly demonstrates how the nuclear family is an effect of responsible citizenry. The governments of these states, Rajasthan being amongst them, insist that those with more than two living children be banned from contesting Panchayat elections or remaining in public office (Buch, 2005).

Singh and Bharadwaj (2000, p. 671) suggest that ‘The state's visualization of the ‘ideal’ family must be read exactly as an effort directed towards laying the foundation of a progressive family’. They go on to contend that ‘Health messages are crafted in a manner that appeals directly to nationalist sentiments underlining the duty of citizens to act as responsible partners in order to “build a better and healthier future for our country”’ (Singh & Bharadwaj, 2000, p. 671). Messages are geared towards mothers in particular, asking them to protect their children by taking them to the health post to be immunised, thereby also implying what is considered good and sanctioned motherhood. Immunisation messages could be crafted towards the citizenry as simple slogans like: ‘Be wise, immunise’; or ‘Be a friend, help eradicate polio’. It is still the middle-class, the well-educated, one- or two-child family that is portrayed in the health information messages in posters, at health centres, at health posts and in ambulating village spectacles arranged regularly by the state health department. In TV advertisements, the ASHA is represented as a humble and informed health sister, always with a mild smile. She visits village homes dressed in a conservative sari draped over the left shoulder; she carries a shoulder purse and has a large red forehead adornment (bindi); and she appears as well fed – all subtle signs of an idealised, middle-class, and middle-caste Hindu woman. We may draw from this that Indian governance in Foucauldian terms is a normalising one intended to modernise the population through bio-political means.

But policies are not made only at the centre and distributed down the hierarchy (Gupta, 2012). Policymaking occurs at all levels where the meaning of the state is constructed and implementation is practised (Gupta, 2012, p. 72). Health bureaucrats interpret, enact and form policies at all levels in the system. In addition, NRHM is widely acknowledged as an outcome of the grassroots pressure generated by India's vibrant democracy, which is capable of influencing government policy in pro-poor directions (Chatterjee, 2011, p. 15; Sen, 1999, p. 152). Over the past decades, popular movements, non-governmental organisations and other forms of grassroots mobilisations have emerged as local and supra-local forces that have buffered, accelerated, ameliorated and even challenged the state's shifting development agendas (Ray & Katzenstein, 2005, p. 4). Rather than understanding policies as instructions flowing down from above, policy implementation should be understood as practises that must be situated in the broader domains of knowledge and power in which they are embedded (Roalkvam et al., 2013). Thus, as Gupta argues, we should not confuse the spectacle of disciplinary power with its operation (2012, p. 14). Sheer contingency underlies the working of what appears as highly rational and well-formulated policies and their implementation. It is to these issues I now turn.

Gender class and caste, technologies of participation

Governmentality implies the cooperation of citizens (Howell, 2006, p. 11). The success of the NRHM is dependent upon women as health workers and as mothers. The NRHM agenda emphasises notions of citizenship and rights, stressing the empowering qualities of the programme (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare [MoHFW], 2005a). Politically, the NRHM's ambition is to make a comprehensive set of health care services available to all and to make communities responsible for meeting their own health needs. Women as health workers and as mothers shall, ideally, determine and identify these needs and become full partners in the decision-making process on health issues.

The most substantial investment by the NRHM in this endeavour is the mobilisation of the rural population through a new health cadre: the ASHA. The ASHA programme represents the most significant investment that the Government of India has made in public health, with the programme responsible for the increase from −0.9% gross domestic product (GDP) to 2–3% GDP in government expenditure in public health (MoHFW, 2005a) According to NRHM guidelines, the ASHA is a community health worker recruited from the community she should serve (MoHFW, 2005a). She is responsible for, a member of, supported by, and accountable to the village health and sanitation committee (VHSC) that is part of the self-governance structure the Panchayati Raj. According to NRHM guidelines, at the village level, the Panchayati Raj should recruit one ASHA (a woman, literate with a minimum of eight years formal education) per 1000 population. The government's expectations of the ASHA are that she is to play a central role in achieving national health and population goals. She is a change agent, a health activist that shall ‘create awareness of health and mobilise the community towards local health planning and increased utilisation and accountability of the existing health services’ (MoHFW, 2005b).

The ASHA receives very limited training. There are frequent complaints both by the ASHA themselves and by health officials that the ASHAs lack knowledge to perform their duties. Most ASHA in Alwar had not completed the stipulated 23 days of training as recommended by the MoHFW, since the courses on specific modules had yet to be offered to them. A majority of the ASHAs in Alwar were not aware of their roles and responsibilities in the VHSC.

The NRHM has set a strict priority to tackle the mother and child health indicators. In the first modules of ASHA training, the health workers are provided with a core pedagogical tool: a training manual clearly linked to the MCPC. The present MCPC, introduced in 2011, is the result of a collaborative effort of the central Ministry of Women and Child Development and the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. The MCPC is the main tool for informing and educating mothers and families on different aspects of maternal and child care, and for linking maternal and child care into a continuum of care through the Integrated Child Development Services scheme of the Ministry of Women and Child Development and the NRHM. As such, the MCPC seems to be a typical health promotion tool aimed at behaviour change, but arguably also a card that can cast mothers and health workers as agents and bearers of entitlements.

According to health bureaucrats, one of the objectives of the MCPC is to assist the ASHA workers as well as the Auxiliary Nurse and Midwives (ANMs) to offer high-quality care to mothers, infants and children. Furthermore, it provides the women's families and children's parents or guardians with information to help them look after the women and children properly. Lastly, it is pivotal for keeping track of maternal and child health management in the villages (i.e. for recordkeeping). The MCPC thus administers the relation between mothers and their families and the health workforce. Importantly, professional expertise remains the controlling actor and defines the terms of interaction. The MCPC communicate professionally what women's most pressing needs are supposed to be and what womanhood is about – the locus of reproduction.

However, the MCPC also carries clear messages on entitlements to services: entitlement to regular check-ups during pregnancy and to childhood immunisation. The card thus explains the minimum package of entitlements (what one may expect from the state). The card also clarifies the corresponding duties – what one should do, as a responsible citizen – for example have one's child weighed at the health centre regularly as well as how to feed, play and communicate with the child to help them grow and develop well. The card also clarifies the responsibilities of the ASHAs towards mothers and children, especially highlighting danger signs that the ASHA needs to be aware of to take immediate action: ‘bleeding during pregnancy’, ‘severe anaemia with or without breathlessness’ and ‘bursting of water bag without labour pains’.

To be user-friendly to both ASHA and mothers, the card is colour-coded. Colours in the card match with colours in the guide developed for training the ASHA (MoHFW, 2011). Yellow has advice and information that the ASHA must explain to the mother and family members. Red denotes danger signs that require immediate contact with a medical provider. Pink is for the ASHA's and ANM's records, and last, blue is important information that the ASHA needs to understand before counselling mothers. All messages are concrete, practical and clearly illustrated. For instance, the three-point messages guiding families to prepare for emergencies are ‘save money’; ‘arrange for transport in emergency’ and ‘identify the hospital in advance’. Another example is the advice given for preparation of home delivery: ‘clean hands’, ‘clean surface and surroundings’, ‘clean blade’, ‘clean umbilical cord’, ‘clean thread to tie the cord’ and last, ‘after delivery, use family planning’. The latter green-coloured areas on the card denote instruction and advice that mothers and families must follow or must ensure that the health worker does correctly: ‘regular check-up is essential during pregnancy’; ‘continue breastfeeding during illness’; ‘always iodized salt for the family’ and ‘have your child weighed at the AW centre regularly’ – to give a few examples (MoHFW, 2011).

The overarching aim of the MCPC is benevolent and intended to safeguard the right to health by pointing to the institutions responsible for taking action. Importantly, rather than clearly linking the right to health to provisions provided by public health institutions, the MCPC links individual rights to the individual and the family, and to their ability to exercise them. As such, the MCPC is a central tool in subject formation – or in the development of responsible citizens.

Although technocratic and seemingly straightforward, the MCPC is complex in the eyes of expectant mothers. All women treasure the MCPC card. The card is well taken care of, wrapped in plastic to hinder wear and tear and stored away safely. Several of the expecting mothers referred to it as a ‘ticket’ that should secure access to services. Yet they also mocked its messages. Particularly, the ‘save money’ message received laughter and jokes. With no work, no money and no job, what was there to save? Household reserves were not available to them. They felt that several of the messages were ill fitted to the realities of how they lived. ‘Arrange for transport’ was similarly subjected to jokes and shared experiences. ‘Transport, what transport? When I was sent to the hospital to give birth I was pulled in a wooden wagon and it took us hours to get there’. ‘I walked’ another young woman explained, ‘accompanied by my mother in law who kept yelling at me to stop complaining’. ‘Ah’ yet another woman complained, ‘my mother in law only took me there for the money – so I had to walk too as she did not want to waste the money offered her to take me there. She did not even allow the sister ASHA to take me as that was wasting money too’.

The ASHA is envisioned as an educational and empowering force to help mothers exercise and claim their rights. This was the case not only in relation to the public services offered them but also in relation to the family, in particular the mother-in-law in charge of most household decisions. In several instances, we witnessed ASHAs urging mother-in-laws to take notice of their daughter-in-laws' health so that they could have healthy grandchildren. Frequently, the ASHA supported the women in relation to their in-laws, opting for less hard work during pregnancy, healthier food and overall improved care. On one particular occasion, a young woman was crying after giving birth to her second daughter, and the ASHA comforted her by saying: ‘Look at me I am a woman. I have work and bring money back to my family. Stop crying, daughters are as clever as sons in looking after their family’.

Yet this approach to governance represents a paradox. On the one hand, there is a bottom-up approach within which villages should take the authority to care for their own health and development and hold governmental officials accountable (i.e. also monitor and appraise the health services given them). However, they must be empowered to do so, hence the top-down approach of professional expertise acting upon a series of hierarchical-structured health workers, all concerned with recordkeeping and the duties of monitoring and surveillance. Within these maternal health polices, however, women's general capacities for agency disappear from sight, whereas their role as mothers, wives and (passive) end-users of new services is highlighted. Paradoxically, the incentives used to enforce this participatory scheme encourage women and health workers to comply with governmental policies and strengthen the view of women as passive end-users of services. We may ask then if efficiency rather than participation is the master concept of NRHM.

The perils of efficiency and participation

Through her training, the ASHA is taught to be an empowering agent in relation to the community (MoHFW, 2005b). The MCPC is one of the main tools that assist the ASHA in this process of increasing the capacity of women and their communities. Paradoxically, perhaps, NRHM is also a market-oriented reform that emphasises the market's role in improving the efficiency and effectiveness of health services. Although NRHM does not leave health services entirely to the market, it creates market-like structures within the confines of public policy (Roalkvam, 2012, p. 245).

To make community health workers and expectant mothers comply with governmental priorities and to keep them motivated, receptive and effective, both expectant mothers and health workers are remunerated by incentives for certain priority tasks defined by the central government. These priority tasks are explicitly linked to maternal and child health indicators. The ASHA is paid incentives for eligible children immunised, women giving birth in governmental facilities and family planning. The ASHA is additionally compensated for her time spent in training and monthly meetings. If she works as expected, she will receive a minimum compensation package of approximately INR 1067 (US$17) per month. Similarly, a cash incentive is available for the expectant mother so that she will give birth in a public facility. She is given INR 1400 (approximately US$28) that should cover her cost for transportation, food, hospital supplies and medicines. A total of INR 300 of the 1400 received is remuneration to the ASHA for accompanying the expectant mother to the clinic. In theory, incentives should cover the actual costs of safe delivery and therefore provide the mother with a care option otherwise not available to her. Yet the definition of her need is based on her identity as a woman and as poor, and on her responsibility for the challenging indicators of maternal and child mortality and morbidity. Although the incentives can strengthen notions of entitlements and rights, incentives also have a heavy surveillance component to them. Women as dependent recipients of predefined welfare take priority over women's agency and capability of choice.

Young mothers in Alwar indeed expressed a longing for good and safe delivery care as well as for comfortable means to limit their pregnancies. But they had no trust that public facilities are capable of offering it to them. In their efforts to explain why, they told me stories about ill treatment by nurses and doctors; doctors who did not appear when needed or that asked for bribes before attending to them; about the fear that hospital staff would perform sterilisation without consent and perform surgery that rendered them weak and unable to work. For these reasons, the care of the village dai (traditional midwife) was often preferred. The incentives for ASHA and expectant mother did not change this preference, as the JSY – safe motherhood programme – was implemented in governmental facilities with poor quality care, high rates of absenteeism and equipment shortages (Roalkvam, 2012, p. 251). The policy regime advocating values such as justice, human dignity and rights did not attempt at improving the quality of care offered in its public health facilities. Women argued that the dismal conditions of the public health facilities were demeaning and a sign of disrespect of poor women. Although women appreciated the presence of the ASHA and her aid, it did not improve trust in the public system.

However, policymakers are not completely ignorant of the lack of trust in public services. At a workshop held in Jaipur at the State Department in Rajasthan (2011), public health state officials explained the ideology and the function of the ASHAs under the NRHM. According to these informants, the most important issue with this new cadre was that the mission needed a new face. A new cadre drawn from the villages should make this new and benevolent effort of the state more visible. It was important to them that the ASHA not become another ANM, an official health worker on the state payroll with proper education, labour unions and demands. The rationale behind this reasoning was twofold. First, putting an ASHA on the state payroll would make her an official state health worker, and thus part of the system these health bureaucrats acknowledged that local communities did not trust. Such a position would severely limit her role as a mobiliser and agent of change. The reason for the ANM's being poorly motivated and unproductive was, according to these informants, her regular salary. The health bureaucrats blamed the ANM for the poor state of public health in the region. To remain a motivated model citizen, the ASHA therefore needed to agree to volunteer her work efforts both to the community and to the state. Her remuneration should therefore be limited and entirely incentive based. Second, the limited training and lack of a career track for ASHAs was motivated, as explained by the same health bureaucrats, by the high costs of the ASHA programme. Training one ASHA per 1000 citizens was a major investment by the state. Limited training and the lack of a career track were ways to retain the community health workers within the community that they were trained to serve, the health bureaucrats argued.

At one of the village health and nutrition days I attended, a heated debate took place between young mothers and ASHA workers. The mothers argued that they felt heavy pressure from the ASHA sisters to give birth in public facilities. The ASHAs defended themselves, arguing that this was the decision of sarkar (government) and that this was necessary in order that they all could have the money that they needed. ‘We spend too much time to make you go to the facility in order that you and I can get the money. If you want us to have the money you should go’. In explaining this controversy, one of the ASHAs turned to me and uttered with approval from the rest of the ASHA group:

They (sarkar) have no idea of what our work is like and they have no appreciation of what we do. We convince women to go to the hospital to give birth. When we get there, there is no doctor. The place is overcrowded. It is dirty and people there are not even nice. We persuade women to go and for what – the place is not even properly equipped. Sometimes the doctor is not even coming out and the baby is delivered as we wait for them to open the door. We are proven as fools. ‘It is all about money’, a young woman expressed eagerly: ‘When I gave birth at the hospital I had to pay bribes both to the doctor and to the nurse and then I have to pay you (pointing at one of the ASHAs present) for taking me there. I had nothing left so why should I go.

Again turning to me to explain, the ASHA expressed that the lack of equipment and the many bribes make women feel that going to the facility is not worth the return. She recognised that the incentives to mothers were the only reason for women to go to a public facility to give birth. Turning to the young mothers, she expressed firmly: ‘You should go. It is the decision of sarkar, that is why sarkar gives you money’.

Although there is an intricate supervisory structure in place to support the ASHA, information does not easily transmit within this chain of command: ‘Sarkar do not listen to us’, one of the ASHAs complained. Upon questioning, health professionals and bureaucrats acknowledge that they are familiar with women's scepticism about the public health system. However, as these practises needed to be changed, they judge this information irrelevant. The ANM and ASHA supervisors are therefore far more concerned with the ASHA's efficiency – they focus on targets, numbers and records.

The ASHA as a community health worker thus represents an interesting paradox (Ferguson & Gupta, 2002). As workers at the bottom of the health system hierarchy (Figure 1), they experience the state as something above them primarily concerned with surveillance and regulation, while they serve as agents of that very same surveillance. Rather than a democratic invitation to voice needs and to participate in health governance, participation is understood as community members buying into the state health project – of bringing children to the immunisation day, registering pregnancies and escorting birthing women to the health facility. Efficiency, not participation, appears then as the master concept that provides the conceptual parameters by which the NRHM's performance, and hence the ASHA's performance, is judged. The claim to efficiency is also the main driver of the subtle pressure that ensures that ASHAs as well as mothers conform to guidelines and priorities as defined by the government. A recent evaluation (Bajpai & Dholakia, 2011, p. 2) of the ASHA programme states that the success of NRHM depends on how efficiently the ASHAs, being the grassroots-level workers, are able to perform, and that the efficiency of ASHAs or efficiency of performance of ASHAs depends on their awareness and perception about their roles and responsibilities (my italics).

Talking back: women as acting subjects

In 2011, I witnessed a village NRHM health spectacle (a theatre) that was touring the area. The play conveyed messages about women and children's health, family planning and immunisation. The women who attended were ANM and ASHA; otherwise, only men witnessed the play. In conveying their messages, the actors were skilfully playing with gender norms and stereotypes to energetic response and laughter from the men present. When the play was almost finished, a group of women approached, all properly veiled, walking tightly together in a group. One of ASHA present cried out:

Look who is coming. Now – when we are almost done! This is about you! You all have husbands and mother-in-laws who do not let you go out in order to learn how you can take care of yourselves!

Her utterance provoked a heated response from an older man present. Shouting back at the ASHA, he reminded her that she was a bahu to this village and hence should know who made the decisions. Bahu is a husband's wife and daughter-in-law, and thus subjected to the authority of her husband and his family. As a young woman, this entails that she remains inside her husband's house – rather than going out into fields – that she covers her face in the presence of senior males and females related by marriage, and when she leaves the house. ‘Not any longer’ the ASHA called back to the old man, ‘women have rights too’. Mockingly, she hastily pulled away the veil from her face – only for a second – before the veil again covered her up as the crowd cracked up in laughter and applause.

The ASHA underscored the joy of the increased mobility the position as village ASHA had given her and the joy of her improved status within the family. In particular, she stressed how the money she brings back to her family has loosened the otherwise strained and controlling relationship to her mother-in-law. She continued highlighting the importance of the ASHA as a model for younger women in the community, a model that could reassert them: ‘Women too have value and women too have equal rights to development’. Working as an ASHA was to her a way of having voice, moving out, being mobile, experiencing some sort of freedom, and indeed becoming modern. Later the same year, she travelled to Jaipur to join hundreds of ASHA workers addressing the then state health minister, demanding more pay and better working conditions. ‘The government appreciates our work; now they should also pay for it’, she uttered.

The remuneration the ASHA receives is a strong motivation for entering the ASHA programme. The ASHAs in Alwar talk with pride about their duties to encourage women to register pregnancies and visit community health centres, escort people to public health centres as needed and bring children to be immunised. They take pride in encouraging family planning, in treating basic illnesses and injuries with first aid, in keeping records and see themselves as possible agents in improving village sanitation. In discussions, they refer to the expectation that they host informational meetings and raise awareness on disease, women's health issues, nutrition and sanitation, and the importance of serving as counsellors on adolescent and female sexual and reproductive health. They also refer to the obligation to attend weekly meetings at the local public health centre with the ANM, under whose authority they perceived they served. In our conversations, they referred repeatedly to themselves as proper health workers, with uniforms, a blue sari, a proper medical kit for basic medicines and with important records to keep. These were all important tokens, they argued, for them to be recognised as proper ASHA. The ASHA themselves were very clear that their authority was a consequence of their being part of the health system, not of being a member of the community. Whereas health bureaucrats judged the middle-caste ASHA as important to win respect in the community, the ASHAs themselves being working women employed and paid by the government as a necessity to move beyond the confinement of gendered caste life.

Yet for all these merits, the ASHA spell out a clear dissatisfaction with sarkar (the government). The ASHAs univocally refer to the people with authority (i.e. people above them in the health system) as sarkar, be they the ANM, the Child Health Manager or District Public Health Officer. In monthly meetings, ASHAs fill out forms, record numbers and relate them to the targets set in the main tasks of immunisation, family planning and childhood immunisation (Mishra, Hasija, & Roalkvam, 2013; Roalkvam et al., 2013). However, these monthly meetings were also an opportunity for ASHA to meet and discuss their experiences with sarkar. The ASHA vigorously debate issues related to the fairness of remuneration. At these meetings the ASHA exchange stories. Complaints from supervisors concerning low output on immunisation are met with stories about the truck of vaccines that never arrived, although all women and eligible children were there waiting for it. A frequent topic of complaint is the ambulance service, be it the driver or the key to the car that is missing, a flat tyre or lack of petrol.

There is, I will suggest, an emerging mobilising effort amongst the ASHA. Whereas the Government of India see the ASHA as the main tool to change maternal and child health practices in the villages, the ASHA themselves are reshaping their position and working conditions. They refuse to buy into the government's view of the ASHA as community volunteers and are increasingly dissatisfied with the present arrangement. In Alwar, there are constant mobilising efforts to jointly call for and argue for better working conditions, be they improved facilities at the hospital or health centres, or the demand that remuneration and provisions for the medical kit be received regularly on fixed and agreed dates. ASHA workers raise issues of health system complaints such as poor quality of care, high rates of absenteeism, shortage of equipment and lack of ambulances publicly. Increasingly, the demand to follow the Uttrakand example is raised where the All India Central Council of Trade Unions affiliated ASHA Health Workers' Union is demanding their rights from the state government. In their mobilising efforts, the ASHA bypass the intricate hierarchical supervisory structure put in place to support them within the health system and form a far more horizontal and egalitarian structure underpinned by the village ASHAs themselves. The storytelling of ASHA experiences is an important corrective to other forms of standard flows of expert knowledge on indicators, targets, input and output, as it conveys evidence of the system's fault lines and how they affect the working of the system. Rather than seeking to impose standard practices, the storytelling exchange is based on a model of seeing and hearing, rather than of teaching and learning. According to Appadurai (2001, p. 37), these practises are nothing less than ‘active participation in the politics of knowledge’ and ‘spontaneous participation in everyday politics’. In short, ‘this is governmentality turned against itself’.

Concluding remarks

I began this paper by arguing that the Government of India's attempt to engage with poor, marginalised rural women, the encounter between mothers and health workers, constitutes both the state and these women's affiliation to it. Within the new Indian state, citizenship is constructed, invoked and substantiated as ways to soften – if not eliminate – class and caste inequalities. At the core of the concept of citizenship lies the contradiction between formal political equality and extensive social and political inequality (Marshall, 1977; Turner, 1990, p. 191). I asked what kind of state is visualised and what kind of citizen is imagined as its responsible partner and in turn how women imagine themselves as citizens.

The focus upon expectant mothers and health workers, I argued, provides means to explore the ways citizenship in neo-liberal reform is enacted, how citizens organise themselves for rights and identities and how they exercise their agency in pursuit. This focus provided insights into the three-sided struggle of neo-liberal health system reform in India. On the one side are proponents of welfare. NRHM is recognised as marking an important step in realising the right to health, that is, entitlements to goods and services, including sexual and reproductive health care and information, and forms a cornerstone of the government's strategy to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity. It can be understood as a vehicle for social justice. Within these ‘benevolent’ and paternalistic maternal health polices, however, women's general capacity for agency disappears from sight, whereas their roles as mothers, wives and passive end-users of services are highlighted. On the other side are the technocratic forces of govermentalisation that represent quite the opposite of social justice – a de-politisation of needs. The emphasis here is on efficiency, costs and individual choice such as consumer choice. NRHM addresses publicly provided services so massively inferior to the commodified counterpart, by emphasising self-worth of the individual and the empowerment of the individual to make good health choices. These abilities are seen as held back by an incompetent state government that needs to be held to account. On the third side is the movement exemplified by the ASHA workers that seek to make the NRHM more democratic and participatory. Acknowledging that waged work alone confers independence and full citizenship, they strongly voice the value of care work as ‘proper work’.

Women are urged into a restructured relationship within NRHM. With its focus on women and children, NRHM is framed as a progressive gender intervention that will enable women to fend for themselves. Paradoxically, however, the NRHM also reinforces the existing gender norms it set out to change. The mobilising efforts of the ASHA re-politicise what neo-liberalism considers private matters best resolved by women themselves. With their mobilising efforts, the ASHA raises a radical critique of the state and the state enterprise and carve out the political space for gendered citizenship so crucially important for NRHM to become a success.

Acknowledgements

I thank Maren Olen Kloster for research assistance. I would like to express my appreciation to PhD research students Cecilie Nordfeldt, and M.Phil students Dagrun Kytre Gjøstein and Synnøve Knivestøen. The Research council of Norway under the Globvac Programme has generously funded the research over seven years between 2008 and 2014. I thank Beena Varghese at the Public Health Foundation in India for being such a great partner and door opener into NRHM. I am extremely grateful to four anonymous reviewers, to Arima Mishra and Katerini T. Storeng for their insightful comments. The research would not have been possible if not for the many people in Alwar, Jajipur and Delhi who made time to meet and share their views and experiences with me.

Funding Statement

Funding: This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway [grant number 196382] – Health system strengthening within vaccination programmes: an ethnographic study (HEALVAC). The Grantee had no impact on the direction, progress, writing or publication of this article.

Note

Ethnographic studies have been undertaken in Alwar, Jaipur, Rajasthan, and New Delhi with a focus upon NRHM, health governance and connections between levels of government. Fieldwork was conducted in relation to three larger research projects funded by the Norwegian Research Council SUM-MEDIC, Explaining Differential Immunization Coverage (2008–2012); HEALVAC: Health systems strengthening within vaccination programmes (2009–2013), funded by the Norwegian Research council and Assessing and Supporting Norwegian and Indian Partnerhip (2008–2010), conducted in collaboration with Public health Foundation in India and funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway [grant number 196382] – Health system strengthening within vaccination programmes: an ethnographic study (HEALVAC). The Grantee had no impact on the direction, progress, writing or publication of this article.

References

- Andersen W. Domestic roots of Indian foreign policy. In: S. Toft Madsen K. B. Nielsen U. Skoda , editor. Trysts with democracy: Political practice in South Asia. London: Anthem Press; 2011. p. XVII, 301. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai A. Deep democracy: Urban governmentality and horizon of politics. Environment and Urbanization. 2001;(2):1–23. doi: 10.1177/095624780101300203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bajpai N., Dholakia R. Improving the performance of accredited social health activists in India; 2011. Retrieved from http://globalcenters.columbia.edu/files/cgc/pictures/Improving_the_Performance_of_ASHAs_in_India_CGCSA_Working_Paper_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Banik D. Growth and hunger in India. Journal of Democracy. 2011;(3):90–104. doi: 10.1353/jod.2011.0049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia M., Rifkin S. A renewed focus on primary health care: Revitalize or reframe? Globalization and Health. 2010;(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch N. Law of two-child norm in Panachayats: Implications, consequences and experiences. Economic and Political Weekly. 2005:2421–2429. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/4416748?uid=2453127375&uid=3739616&uid=2129&uid=2134&uid=2&uid=70&uid=3&uid=67&uid=20457&uid=62&uid=3739256&sid=21104237005247. [Google Scholar]

- Census Rajasthan population census data. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.census2011.co.in/census/state/rajasthan.html.

- Chatterjee P. Democracy and economic transformation in India. Economic and Political Weekly. 2008;(16):53–62. doi: 10.2307/40277640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee P. Lineages of political society: Studies in postcolonial democracy. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury A. M., Bhuiya A., Chowdhury M. E., Rasheed S., Hussain Z., Chen L. The Bangladesh paradox: Exceptional health achievement despite economic poverty. The Lancet. 2013:1734–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbridge S., Williams G., Srivastada M., Véron R. Seeing the state: Governance and governmentality in India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Devanandan P. D., Thomas M. M. The changing pattern of family in India. Bangalore: Christian Institute for the Study of Religion and Society; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Drèze J., Sen A. An uncertain glory: India and its contradictions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson J., Gupta A. Spatializing states: Toward an ethnography of neoliberal governmentality. American Ethnologist. 2002:981–1002. doi: 10.1525/ae.2002.29.4.981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes L., Heller P. New middle class politics and India's democracy in comparative perspective. In: R. J. Herring R. Agarwala , editor. Whatever happened to class? Reflections from South Asia. Delhi: Daanish Books; 2008. pp. 146–165. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Governmentality. In: G. Burchell C. Gordon P. Miller , editor. The Foucault effect: Studies in governmentality. London: Wheatsheaf; 1991. pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Ethics: Subjectivity and truth. New York, NY: The New Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Security, territory, population. New York, NY: Palgrave; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser N., Bedford W. K. Social rights and gender justice in the neoliberal moment: A conversation about welfare and transnational politics. Feminist Theory. 2008:225–245. doi: 10.1177/1464700108090412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S. NIPI baseline survey on child and related maternal care. 2009 Retrieved from http://s3.amazonaws.com/zanran_storage/nipi.org.in/ContentPages/2559228976.pdf.

- Gupta A. Red tape: Bureaucracy, structural violence and poverty in India. Durham: Duke University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A., Sharma A. Globalization and postcolonial states. Current Anthropology. 2006:277–307. Retrieved from http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic543017.files/Speaking%20Like%20a%20State/Required/Gupta_Sharma_Globalization_PostcolonialState.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges S. Governmentality, population and reproductive family in modern India. Economic and Political Weekly. 2004:1157–1163. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/4414767?uid=2453127375&uid=3739616&uid=2129&uid=2134&uid=2&uid=70&uid=3&uid=67&uid=20457&uid=62&uid=3739256&sid=21104237005247. [Google Scholar]

- Howell S. The kinning of foreigners: Transnational adoption in a global perspective. New York, NY: Berghahn Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur R. Nation's two bodies: Rethinking the idea of ‘new’ India and its other. Third World Quarterly. 2012:603–621. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2012.657420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall T. H. Citizenship and social development: Essays by T.H. Marshall. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare NRHM: Mission document. 2005a Retrieved from http://mohfw.nic.in/NRHM/Documents/NRHM%20Mission%20Document.pdf.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare ASHA. 2005b Retrieved from http://mohfw.nic.in/NRHM/asha.htm.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare A guide for use for the mother-child protection card for the community and the family AWW, ANM & sector supervisors; 2011. Retrieved from http://hetv.org/pdf/protection-card/mcp-english.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A., Hasija S., Roalkvam S. “Numerical narratives”: Accounts of lay health workers in Odisha. In: A. Mishra S. C. Chatterjee , editor. Multiple voices and atories: Narratives of health and illness. Delhi: Orient Blackswan Private Limited; 2013. pp. 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A., Roalkvam S. The reproductive body and the state: Engaging with the National Rural Health Mission in tribal Odisha. In: K. B. Nielsen A. Waldrop , editor. Women, gender and everyday social transformation in India. London: Anthem Press; 2014. pp. 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Nordfeldt C., Roalkvam S. Choosing vaccination: Negotiating child protection and good citizenship in modern India. Forum for Development Studies. 2010:327–347. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2010.513402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul B., Mohapatra B., Kar K. Maternal deaths in a tertiary health care centre of Odisha: An in-depth study supplemented by verbal autopsy. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2011:213–216. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.86523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R., Katzenstein M. F. Introduction: In the beginning, there was the Nehruvian state. In: R. Ray M. F. Katzenstein , editor. Social movements in India: Poverty, power, and politics. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2005. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Roalkvam S. Stripped of rights in the pursuit of the good: The politics of gender and the reproductive body in Rajasthan, India. In: K. Bjørkdahl K. B. Nielsen , editor. Development and environment: Practices, theories, policies. Oslo: Akademika; 2012. pp. 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Roalkvam S., McNeill D., Blume S. Protecting the world's children: Immunisation policies and practices. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. What's happening in Bangladesh? The Lancet. 2013;382:1966–1968. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M. S., Bharadwaj A. Communicating immunisation: The mass media strategies. Economic and Political Weekly. 2000:667–675. doi: 10.2307/4408963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank Maternal mortality ratio. 2013 Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT.

- Turner B. S. Outline of a theory of citizenship. Sociology. 1990:189–214. doi: 10.1177/0038038590024002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Rights-based legal guarantee as development policy: The Mahatma Gandhi national employment rural guarantee act. New Delhi: UNDP India; 2010. [Google Scholar]