Abstract

Objective: The etiology of endometriosis is still a research field in which few consistent data are available. Large case–control studies or even cohort studies are rare, and most of the published data are conflicting. The aim of the present study was therefore to examine common epidemiological and endometriosis-specific risk factors in a German case–control study. Design: From 2001 to 2010, a pool of 595 laparoscopically confirmed cases and 475 controls were recruited in a hospital-based setting. After matching for age, 298 cases and 300 controls remained in the pool. Age at menarche, menstrual cycle length, duration of menstrual bleeding, number of pregnancies, live births, miscarriages, use of contraceptive pills, body mass index (BMI), and smoking status were analyzed with logistic regression models predicting endometriosis case–control status. Results: Menstrual cycle length, duration of menstrual bleeding, number of pregnancies, number of miscarriages, and smoking status, as relevant predictors for endometriosis case–control status, were identified as risk factors for endometriosis. Other factors such as age at menarche, number of live births, ever having used contraceptive pills, and BMI were not predictive. Conclusions: This hospital-based case–control study reproduced most of the familiar risk factors. Comparison of this study with others reveals a wide variety of effect sizes and directions of association with risk factors and may increase the information available about the characteristics of the patient population being treated in the relevant hospital setting.

Key words: endometriosis, risk factor, case-control study, epidemiology, genetics

Abstract

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung: Die Ätiologie der Endometriose bleibt ein Forschungsgebiet mit spärlichen Erkenntnissen. Große Fall-Kontroll-Studien oder Kohortenstudien sind selten, und die publizierten Daten widersprechen sich auf den ersten Blick zum größten Teil. Ziel unserer Studie war es deswegen, in einer deutschen Fall-Kontroll-Studie Risikofaktoren zu identifizieren und zu beschreiben. Methoden: Von 2001 bis 2010 wurde ein Pool von 595 laparoskopisch diagnostizierten Endometriosepatientinnen und 475 in einem krankenhausbasierten Design rekrutiert. Von diesem Pool wurden 298 Fälle und 300 Kontrollen altersgematched. Ergebnisse: Alter bei der Menarche, Zyklusdauer, Dauer der Periodenblutung, Anzahl der Schwangerschaften und Lebendgeburten, Fehlgeburten, Pilleneinnahme, Body-Mass-Index (BMI) und Raucherstatus wurden in logistischen Regressionsmodellen auf ihre Prädiktion für den Endometriose-Fall-Kontroll-Status untersucht. Dauer der Periodenblutung, Dauer des Zyklus, Anzahl der Schwangerschaften, Anzahl der Fehlgeburten und Raucherstatus waren relevante und signifikante Risikofaktoren für die Endometriose. Die anderen Faktoren wie Alter bei Menarche, Anzahl der Lebendgeburten, Pillennutzung und BMI waren im multivariaten Modell nicht prädiktiv in Bezug auf den Fall-Kontroll-Status. In dieser krankenhausbasierten Fall-Kontroll-Studie konnten die meisten, bekannten Risikofaktoren für eine Endometrioseerkrankung reproduziert werden. Schlussfolgerung: Vergleicht man die Studie mit anderen, so fällt auf, dass die Variabilität der Effektstärke und der Richtung der Prädiktion für die Risikofaktoren in den meisten Studien unterschiedlich ist. Die Analyse der Risikofaktoren im eigenen Kollektiv könnte helfen, die Population der Endometriosepatientinnen besser zu verstehen, die im entsprechenden Krankenhaus behandelt werden.

Schlüsselwörter: Endometriose, Risiko, Fall-Kontroll-Studie, Epidemiologie, Genetik

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic disease that affects 4–30 % of all women of reproductive age 1, 2, 3. It is also one of the most frequent gynecological diseases. The prevalence of endometriosis in women who present with infertility problems is even higher (up to 50 %) 3, 4, 5, 6. However it can reasonably be assumed that the prevalence is about 10 % 3. Pelvic pain during menstruation is the main symptom in patients with endometriosis. The disease is characterized by the presence of endometrial cells outside the uterus. They are located mainly in the rectouterine pouch, but can also be found in the vesicouterine pouch, abdominal wall, ovaries, and uterus 7, 8, 9, and may also be more widespread at more unusual locations 10.

The increased rate of the disease among first-degree relatives of patients with endometriosis may also suggest a genetic predisposition 11. Due to the recurrent nature of the condition, which hinders women in their occupational and private lives, endometriosis creates substantial health-care costs, which have been estimated as exceeding $ 22 billion in the United States in 2002 12 and totaling approximately € 2 billion (2 000 000 000) in Germany 13.

Treatment options mainly consist of medication and surgical therapy. Surgical removal of the lesion is often the first-line therapy. Surgical treatment using minimally invasive approaches is usually preferred, but more extensive surgery may become necessary in cases of deeply infiltrating endometriosis 14, 15. About 19–45 % of all endometriosis patients suffer one or more recurrences within 5 years, leading to repeated operations in many patients 16, 17, 18, 19, 20. Medication includes treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antihormonal treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs, or aromatase inhibitors 21, 22, 23. Some forms of treatment, such the selective estrogen receptor modulator raloxifene, even shorten the time to recurrence in endometriosis patients 24.

The pathogenesis of endometriosis is considered to be complex. Historically a metaplastic transformation of peritoneal cells or the still favourably discussed retrograde menstruation of endometrial cells through the tubes into the peritoneal cavity 26. On a molecular level different pathways such as the estrogen and progesterone pathway, vasculogenesis, sphingolipids, prostaglandins, and cytokines appear to be involved 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35. Some information has been obtained about the etiology, but there is a lack of large case–control studies on the disease and especially of studies using a population-based design.

There have been several reports linking characteristics of the menstrual cycle with endometriosis, such as age at menarche, duration of menstruation, and length of the cycle 2, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42. It is thought that an increased frequency of and duration of menstruations is associated with endometriosis. This applies to risk factors such as early menarche, long duration of menstruation, short menstrual cycles, and lower parity. However, the data are not consistent with regard to risk estimates or the direction of the risk.

Similarly inconsistent data have been reported for other risk factors such as body mass index (BMI), physical activity, and smoking. There are some data suggesting an inverse relationship between BMI and endometriosis, but many studies have not found this association 43. The Nursesʼ Health Study observed women prospectively and found no clear association between physical activity and endometriosis 44. There are also inconsistent data with regard to smoking. It has been reported that smoking reduces the estrogen level and thus the risk of endometriosis 40, but other studies did not identify any influence on the risk. There are also no differences between active and former smokers 2, 45.

Although the pathogenesis and etiology are poorly understood, there have been several studies that strengthen the hypothesis that endometriosis has complex genetic traits 46, 47, 48. Familial clustering has been described in several studies 49, 50. A large linkage analysis including more than 1100 families with at least two cases of endometriosis in the family identified two loci, one on chromosome 10q26 and another on chromosome 20p13 51. However, follow-up candidate gene studies in these regions did not identify a specific gene or genetic variation 52.

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) in Japan identified a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in CDKN2B-AS and an SNP close to WNT4 at the genome-wide significance level 53. A GWAS conducted in Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom also identified an SNP in proximity to NFE2L3 and HOXA10.

As the genetic causes of endometriosis are being investigated in more detail, the aim of the present investigation was to conduct a case–control study with epidemiological data to allow analysis not only of the genetic causes of the disease, but also of gene-environment interactions. This study reports on the clinical data from this case–control study.

Patients and Methods

This analysis is based on 298 endometriosis cases and 300 controls, who were recruited between 2001 and 2010 in a pool of 595 endometriosis patients and 475 healthy controls as part of a hospital-based case–control study, the Bavarian Endometriosis Study (BENS). Women were eligible if they were aged at least 18 and were willing to complete an epidemiological questionnaire and provide a blood sample for genetic analysis. They were recruited as endometriosis patients if the disease was confirmed by surgery, either macroscopically (n = 18) or with histological examination (n = 281). Controls were eligible if they reported no previous abdominal surgery and no pelvic pain syndrome. All of the women provided written informed consent, and the ethics committee of the institutionʼs medical faculty approved the study.

All of the women completed a structured and assisted questionnaire designed to provide comprehensive epidemiological risk factor data on their previous reproductive history, menstrual cycle characteristics, previous medical history, family history, and lifestyle factors. The questionnaire has previously been used in other case–control studies on breast cancer 54, 55, 56. In addition to these parameters, specific questions were asked about endometriosis, such as previous operations and pelvic pain characteristics (lower bowel pain, dyschezia, dysuria, and dyspareunia).

Endometriosis had to be confirmed either histologically or macroscopically. The information was obtained either from the original surgery reports or the pathological reports from the patient charts.

Statistical considerations

The cases and controls were matched at a ratio of 1 : 1 by age at the time of diagnosis and interview, respectively, within deciles. Characteristics of cases and controls are presented as means and standard deviations, or counts and percentages. For each characteristic, a simple logistic regression model was used to calculate unadjusted odds ratios (OR) and the corresponding 95 % confidence intervals.

Multifactorial logistic regression analyses were carried out with the predictors age at menarche, menstrual cycle length, duration of menstrual bleeding, number of pregnancies, number of live births, number of miscarriages, use of contraceptive pills at any time, BMI, and smoking status, categorized as shown in Table 1 to identify a set of predictors that were together associated with endometriosis case–control status. Five hundred bootstrap samples of the same size as the data set were selected with replacement. For each bootstrap sample, a stepwise backward logistic model selection procedure starting with all predictors was carried out to obtain the best model according to the Akaike information criterion. The retained predictors from each bootstrap sample were recorded, and a final variable selection was made by applying a procedure proposed by Sauerbrei and Schumacher 57 to our setting. In this procedure, the most frequent (> 70 %) predictors were selected, and, because of correlation, the predictor with the larger frequency out of each highly frequent predictor pair (> 90 %) was chosen. A multifactorial logistic regression model using these finally selected predictors was fitted to calculate adjusted ORs with its 95 % confidence intervals. Repetitive variable selections were carried out to stabilize the stepwise regression results 58.

Table 1 Patient characteristics of endometriosis cases and healthy controls.

| Patient characteristics | Cases | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 37.2 (± 8.7) | 37.3 (± 9.4) |

| Age at menarche (years) | ≤ 11 | 48 (16.5 %) | 26 (8.9 %) |

| 12 | 79 (27.1 %) | 85 (29.1 %) | |

| 13 | 84 (28.9 %) | 72 (24.7 %) | |

| 14 | 49 (16.8 %) | 71 (24.3 %) | |

| ≥ 15 | 31 (10.7 %) | 38 (13.0 %) | |

| Menstrual cycle length (days) | ≤ 27 | 71 (31.8 %) | 96 (35.0 %) |

| 28 | 79 (35.4 %) | 121 (44.2 %) | |

| ≥ 29 | 73 (32.7 %) | 57 (20.8 %) | |

| Duration of menstrual bleeding (days) | ≤ 4 | 78 (31.2 %) | 123 (43.9 %) |

| 5 | 71 (28.4 %) | 80 (28.6 %) | |

| ≥ 6 | 101 (40.4 %) | 77 (27.5 %) | |

| Number of pregnancies | 0 | 157 (53.2 %) | 107 (35.8 %) |

| 1 | 61 (20.7 %) | 55 (18.4 %) | |

| 2 | 47 (15.9 %) | 69 (23.1 %) | |

| ≥ 3 | 30 (10.2 %) | 68 (22.7 %) | |

| Number of live births | 0 | 181 (61.4 %) | 130 (43.6 %) |

| 1 | 57 (19.3 %) | 67 (22.5 %) | |

| 2 | 44 (14.9 %) | 70 (23.5 %) | |

| ≥ 3 | 13 (4.4 %) | 31 (10.4 %) | |

| Number of miscarriages | 0 | 253 (86.3 %) | 252 (84.6 %) |

| ≥ 1 | 40 (13.7 %) | 46 (15.4 %) | |

| Use of contraceptive pill, ever | 0 | 52 (18.4 %) | 29 (9.7 %) |

| 1 | 231 (81.6 %) | 269 (90.3 %) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ≤ 20 | 31 (12.3 %) | 36 (12.3 %) |

| 20–25 | 163 (64.4 %) | 188 (64.2 %) | |

| 25–30 | 45 (17.8 %) | 51 (17.4 %) | |

| > 30 | 14 (5.5 %) | 18 (6.1 %) | |

| Smoking | no | 102 (41.6 %) | 176 (59.9 %) |

| yes | 143 (58.4 %) | 118 (40.1 %) |

The predictive ability of the final model was measured by the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristics. The AUC ranges from 0.5 (random prediction) to 1 (perfect prediction). In relation to overfitting, the AUC was evaluated with 10-fold cross-validation with 20 repetitions and with the 0.632+ bootstrapping method with 500 bootstrap samples 59, 60.

All of the tests were two-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Calculations were carried out using the R system for statistical computing (version 2.13.1; R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria, 2011).

Results

From a pool of 595 endometriosis patients and 475 controls, 298 endometriosis patients and 300 controls remained for the final analysis after matching for age. The average age of cases was 37.2 (± 8.7), while that of controls was 37.3 (± 9.4). Common patient characteristics for cases and controls are presented in Table 1.

In the univariate analysis, age at menarche, menstrual cycle length, parity, number of miscarriages, and smoking status were found to differ significantly between cases and controls. Women with a higher age at menarche seemed to have a lower likelihood of being in the group of cases. The OR for women aged 15 or older at the time of menarche was 0.44 (95 % CI, 0.23 to 0.87) in comparison with women who had the menarche at age 11 or earlier. Similarly, the groups of women who had the menarche at ages 12 and 14 had a lower likelihood of being in the case group (Table 2). Women with a longer menstrual cycle (≥ 29 vs. ≤ 27 days) were more likely to be endometriosis patients (OR 1.73; 95 % CI, 1.09–2.75). Women who had a longer duration of menstrual bleeding had an OR of 1.48 (95 % CI, 0.96–2.29), but this was not significant in the univariate analysis (Table 2). Numbers of pregnancies and numbers of live births were distributed in a clearly ordinal way. The more pregnancies or live births were reported, the less likely the woman was to be in the group of endometriosis patients (Table 2). Women with three or more pregnancies had an OR of 0.30 (95 % CI, 0.18–0.49). Use of oral contraceptives was also seen less often among cases (OR 0.48; 95 % CI, 0.29–0.78) and smoking was more prevalent in cases (OR 2.09; 95 % CI, 1.48–2.95). BMI and number of miscarriages were not associated with case–control status (Table 2). However, the number of miscarriages is not independent of the number of pregnancies.

Table 2 Odds ratio (OR) for endometriosis cases and healthy controls in relation to patient characteristics (predictors).The unadjusted and adjusted OR, with 95 % confidence intervals in brackets, and the corresponding p values are shown.

| Predictor | Values | OR unadjusted1 | p value | OR adjusted2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 OR estimated with simple logistic regression models; one model per predictor. 2 OR estimated by a multifactorial logistic regression model with variable selection, as described in the statistical methods section. ORs are adjusted for all other predictors. 3 The predictors age at menarche, number of live births, use of contraceptive pills ever, and body mass index were dropped during the variable selection process. | |||||

| Age at menarche (years) | ≤ 11 | 1.00 (reference) | – | – 3 | |

| 12 | 0.50 (0.29, 0.89) | 0.02 | |||

| 13 | 0.63 (0.36, 1.12) | 0.12 | |||

| 14 | 0.37 (0.21, 0.68) | < 0.01 | |||

| ≥ 15 | 0.44 (0.23, 0.87) | 0.02 | |||

| Menstrual cycle length (days) | ≤ 27 | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| 28 | 0.88 (0.58, 1.34) | 0.56 | 0.71 (0.43, 1.18) | 0.19 | |

| ≥ 29 | 1.73 (1.09, 2.75) | 0.02 | 2.33 (1.34, 4.04) | < 0.01 | |

| Duration of menstrual bleeding (days) | ≤ 4 | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| 5 | 0.71 (0.47, 1.10) | 0.12 | 0.84 (0.48, 1.45) | 0.53 | |

| ≥ 6 | 1.48 (0.96, 2.29) | 0.08 | 1.86 (1.07, 3.24) | 0.03 | |

| Number of pregnancies | 0 | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| 1 | 0.76 (0.49,1.18) | 0.21 | 0.71 (0.40, 1.28) | 0.25 | |

| 2 | 0.46 (0.29,0.72) | < 0.001 | 0.48 (0.27, 0.88) | 0.02 | |

| ≥ 3 | 0.30 (0.18,0.49) | < 0.00001 | 0.17 (0.08, 0.40) | < 0.0001 | |

| Number of live births | 0 | 1.00 (reference) | – | – 3 | |

| 1 | 0.61 (0.40,0.93) | 0.02 | |||

| 2 | 0.45 (0.29,0.70) | < 0.001 | |||

| ≥ 3 | 0.30 (0.15,0.60) | < 0.001 | |||

| Number of miscarriages | 0 | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| ≥ 1 | 0.87 (0.55,1.38) | 0.54 | 2.76 (1.28, 5.93) | < 0.01 | |

| Use of contraceptive pill, ever | no | 1.00 (reference) | – | – 3 | |

| yes | 0.48 (0.29,0.78) | < 0.01 | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ≤ 20 | 1.00 (reference) | – | – 3 | |

| 20–25 | 1.01 (0.60, 1.70) | 0.98 | |||

| 25–30 | 1.02 (0.55, 1.92) | 0.94 | |||

| > 30 | 0.90 (0.39, 2.11) | 0.81 | |||

| Smoking | no | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| yes | 2.09 (1.48,2.95) | < 0.0001 | 2.16 (1.39, 3.36) | < 0.001 | |

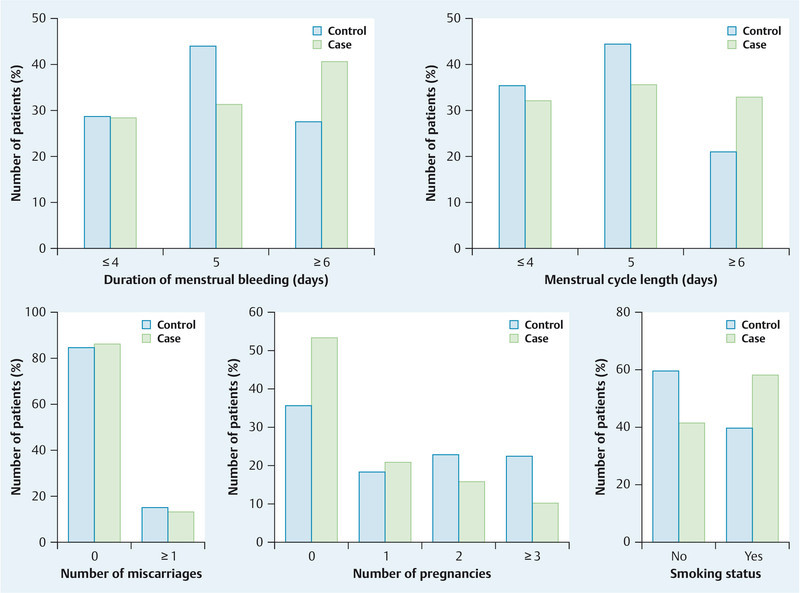

With regard to the multifactorial analysis, the variable selection process described above in the statistical methods section identified menstrual cycle length, duration of menstrual bleeding, number of pregnancies, number of miscarriages, and smoking status as relevant predictors for endometriosis case–control status (Table 2). The other predictors considered – age at menarche, number of live births, use of contraceptive pills at any time, and BMI – were not selected for the final logistic regression model. This means that their predictive values appeared to be irrelevant, or that they can already be explained by the selected predictors. Menstrual cycle length and duration of menstrual bleeding were positively associated with endometriosis and had adjusted ORs of 2.33 (95 % CI, 1.34–4.04) and 1.86 (95 % CI, 1.07–3.24), respectively. The inverse association with the number of pregnancies was even stronger, with an adjusted OR of 0.17 (95 % CI, 0.08–0.40) among women with three or more pregnancies, in comparison with the univariate analysis. Having one or more miscarriages in the medical history was identified as a statistically significant risk factor (adjusted OR 2.76; 95 % CI, 1.28–5.93) independent of the number of pregnancies, for instance. Smoking status continued to show a significant association, with an adjusted OR of 2.16 (95 % CI, 1.39–3.36). Fig. 1 provides an overview of the distribution of the risk factors finally selected in this case–control study.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of risk factors between cases and controls.

The apparent AUC value of the final regression model was 0.72, while the bootstrap-validated and cross-validated AUCs were both 0.68.

Discussion

Certain menstrual cycle characteristics, pregnancies, miscarriages, and smoking were identified as risk factors associated with endometriosis in this case–control study in Germany. Body mass index did not show any association.

Most of the results are in line with previously published studies, although some are not. With regard to menstrual cycle characteristics, it has been hypothesized that increasing exposure to menstrual bleeding is a risk factor for endometriosis 2, 38, 39, 40, 41, implying that early menarche, short cycles, longer duration of menstrual bleeding, and fewer pregnancies are risk factors. The present study confirms the duration of menstrual bleeding as a risk factor, but showed conflicting results with regard to the length of the menstrual cycle. Cases had a longer menstrual cycle, but the categorization differed from some other studies, as most of the participants in this study had fairly regular cycles, with most women having a cycle length of 28 days. Other studies have constructed categories ranging from ≤ 24 days to ≥ 31 days, resulting in categories with very small sample sizes and wide confidence intervals 42. Another study has reported no association and show differences depending on which controls were used for the comparison 2. A cohort study with data for cycle length in 688 women showed no association between cycle length and endometriosis in the overall group of women, but did find an association in the group of women with no history of infertility 40.

The present study clearly shows an inverse association between the number of pregnancies and endometriosis, and a positive association between the number of miscarriages and endometriosis. This has also been observed in most of the published studies on the etiology of endometriosis. The Nursesʼ Health Study II reported that the risk of endometriosis declines with an increasing number of pregnancies. This effect was clearly evident in women with no history of infertility and somewhat weaker in women with previous or concurrent infertility 40. The relative risk in women with no pregnancies was 1.4 (95 % CI, 1.2–1.6) in comparison with women with two pregnancies. The effect size in the present study is comparable to that in other case–control studies 41.

The present study is also more consistent with other reports describing no association between endometriosis and BMI 2, 5, 61. However, there have been several studies reporting an association between low BMI and endometriosis 36, 40, 62, 63. In the Nursesʼ Health Study II cohort, physical activity was not strongly associated with the endometriosis risk 44.

In the present study, smoking was a clear risk factor in both the univariate analysis and the multivariate model. As with all the other risk factors described, published studies have both identified and also failed to identify associations between smoking and endometriosis. Three larger case–control studies reported no difference between cases and controls with regard to smoking status 61, 62, 64. Two earlier case–control studies also reported no relationship 2, 36. The present study showed a positive association between smoking (past and current) and endometriosis. The Nursesʼ Health Study II reported a more complex relationship between endometriosis and smoking status. In women who reported never having had an infertility problem, there was a positive correlation between smoking status and endometriosis, whereas the association was inverse in the group of patients with an infertility history 65.

This study has several limitations and strengths. In endometriosis case–control studies, not only the selection of controls but also the selection of cases is critical with regard to the possible results. Case selection in a hospital-based study may be biased by the variety of health care that is provided in the hospital concerned. Women seeking help for pelvic pain might increase the numbers of cases of pain-inducing endometriosis, and a hospital with specialized health care for infertility patients might have larger numbers of patients in that subgroup. In the present study, the hospital is a center for all types of treatment, so that a bias for one of these groups seems unlikely. No previous abdominal surgery was required for the controls, in order to exclude any bias regarding the reason for surgery. This group might have larger numbers of women with less pelvic pain. However, a clear limitation is that the study is not population-based, so that any selection bias could influence the results.

One strength of the study is the robust selection of the variables during the bootstrap validation procedure, which yielded stable variable selection results. The final model predicted case–control status quite well, with a validated AUC of 0.68.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study show both consistencies and inconsistencies with other published studies for almost every risk factor. It is difficult for both patients and physicians to use the available information 66. Only the number of pregnancies and the duration of menstrual bleeding appear to be consistent throughout the published studies and in this German case–control study. Assessing risk estimates in the population as determined in a hospital setting might improve our understanding of the nature of the condition for treatment of endometriosis patients and might also help identify differences between clinical varieties of endometriosis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

References

- 1.Bulun S E. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:268–279. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Signorello L B, Harlow B L, Cramer D W. et al. Epidemiologic determinants of endometriosis: a hospital-based case-control study. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7:267–274. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vigano P, Parazzini F, Somigliana E. et al. Endometriosis: epidemiology and aetiological factors. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18:177–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahmood T A, Templeton A. Prevalence and genesis of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:544–549. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moen M H, Schei B. Epidemiology of endometriosis in a Norwegian county. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:559–562. doi: 10.3109/00016349709024584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Witz C A, Burns W N. Endometriosis and infertility: is there a cause and effect relationship? Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2002;53 01:2–11. doi: 10.1159/000049418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mechsner S, Infanger M, Ebert A D. et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis – diagnosis and therapeutic management. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2010;70:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wobser M, Seitz C S, Becker J C. et al. Umbilical endometriosis. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2009;69:331–333. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krentel H, Hucke J. Disseminated hormone-producing leiomyomatosis after laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy: a case report. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2010;70:894–897. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goppel K, Becker K, Schmalfeldt B. et al. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata – four case reports of a rare disease. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2009;69:945–951. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simpson J L, Elias S, Malinak L R. et al. Heritable aspects of endometriosis. I. Genetic studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;137:327–331. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)90917-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simoens S, Hummelshoj L, DʼHooghe T. Endometriosis: cost estimates and methodological perspective. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:395–404. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandes I, Kleine-Budde K, Mittendorf T. Cost of illness of endometriosis. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2009;69:925–930. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardanis K, Zdichavsky M, Kramer M. et al. Minimally invasive surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis in the rectovaginal septum. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2010;70:194–200. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weichbrodt M, Gericke J, Riedlinger W F. et al. Is sentinel lymph node examination in patients with deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis beneficial? Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2010;70:391–396. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evers J L Dunselman G A Land J A et al. Is there a solution for recurrent endometriosis? Br J Clin Pract Suppl 19917245–50.discussion: 51-43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redwine D B. Conservative laparoscopic excision of endometriosis by sharp dissection: life table analysis of reoperation and persistent or recurrent disease. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:628–634. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renner S P, Ekici A B, Maihofner C. et al. Neurokinin 1 receptor gene polymorphism might be correlated with recurrence rates in endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25:726–733. doi: 10.3109/09513590903159631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renner S P, Rix S, Boosz A. et al. Preoperative pain and recurrence risk in patients with peritoneal endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:230–235. doi: 10.1080/09513590903159623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wheeler J M, Malinak L R. Recurrent endometriosis: incidence, management, and prognosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;146:247–253. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90744-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen C Hopewell S Prentice A Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain in women with endometriosis Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20054CD004753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoshiai H, Terakawa N. Novel therapeutic targets for GnRH analogues in the treatment of endometriosis and current approaches to optimizing GnRH analogue therapy. Introduction. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2008;66 01:1–2. doi: 10.1159/000148024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nawathe A, Patwardhan S, Yates D. et al. Systematic review of the effects of aromatase inhibitors on pain associated with endometriosis. Bjog. 2008;115:818–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stratton P, Sinaii N, Segars J. et al. Return of chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis after raloxifene treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:88–96. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000297307.35024.b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer R. Ueber den Stand der Frage der Adenomyositis, Adenomyome im Allgemeinen und insbesondere über Adenomyositis seroepithelialis und Adenomyometritis sarcomatosa. Zentralbl Gynakol. 1919;36:745–750. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sampson J. Peritoneal endometriosis due to menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obst Gynecol. 1927;14:442–469. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tseng J F, Ryan I P, Milam T D. et al. Interleukin-6 secretion in vitro is up-regulated in ectopic and eutopic endometrial stromal cells from women with endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:1118–1122. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.3.8772585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kao L C, Germeyer A, Tulac S. et al. Expression profiling of endometrium from women with endometriosis reveals candidate genes for disease-based implantation failure and infertility. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2870–2881. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kao L C, Tulac S, Lobo S. et al. Global gene profiling in human endometrium during the window of implantation. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2119–2138. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noble L S, Simpson E R, Johns A. et al. Aromatase expression in endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:174–179. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.1.8550748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bulun S E, Zeitoun K, Takayama K. et al. Estrogen production in endometriosis and use of aromatase inhibitors to treat endometriosis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6:293–301. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noble L S, Takayama K, Zeitoun K M. et al. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates aromatase expression in endometriosis-derived stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:600–606. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burney R O, Hamilton A E, Aghajanova L. et al. MicroRNA expression profiling of eutopic secretory endometrium in women with versus without endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2009;15:625–631. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burney R O, Talbi S, Hamilton A E. et al. Gene expression analysis of endometrium reveals progesterone resistance and candidate susceptibility genes in women with endometriosis. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3814–3826. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaetje R, Holtrich U, Engels K. et al. Does sphingosine kinase 1 (SPHK1) play a role in endometriosis? Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2009;69:935–939. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berube S, Marcoux S, Maheux R. Canadian Collaborative Group on Endometriosis . Characteristics related to the prevalence of minimal or mild endometriosis in infertile women. Epidemiology. 1998;9:504–510. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cramer D W, Wilson E, Stillman R J. et al. The relation of endometriosis to menstrual characteristics, smoking, and exercise. JAMA. 1986;255:1904–1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eskenazi B, Warner M L. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1997;24:235–258. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Metzger D A, Haney A F. Etiology of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Missmer S A, Hankinson S E, Spiegelman D. et al. Reproductive history and endometriosis among premenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:965–974. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000142714.54857.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parazzini F, Ferraroni M, Fedele L. et al. Pelvic endometriosis: reproductive and menstrual risk factors at different stages in Lombardy, northern Italy. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49:61–64. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Treloar S A Bell T A Nagle C M et al. Early menstrual characteristics associated with subsequent diagnosis of endometriosis Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010202534e531–e536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lafay Pillet M C Schneider A Borghese B et al. Deep infiltrating endometriosis is associated with markedly lower body mass index: a 476 case–control study Hum Reprodadvance online publication 24October2011 10.1093/humrep/der346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vitonis A F, Hankinson S E, Hornstein M D. et al. Adult physical activity and endometriosis risk. Epidemiology. 2010;21:16–23. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c15d40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heilier J F, Donnez J, Nackers F. et al. Environmental and host-associated risk factors in endometriosis and deep endometriotic nodules: a matched case-control study. Environ Res. 2007;103:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simpson J L, Bischoff F. Heritability and candidate genes for endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2003;7:162–169. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61746-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kennedy S. Genetics of endometriosis: a review of the positional cloning approaches. Semin Reprod Med. 2003;21:111–118. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giudice L C. Genomicsʼ role in understanding the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2003;21:119–124. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kennedy S, Mardon H, Barlow D. Familial endometriosis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1995;12:32–34. doi: 10.1007/BF02214126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stefansson H, Geirsson R T, Steinthorsdottir V. et al. Genetic factors contribute to the risk of developing endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:555–559. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Treloar S A, Wicks J, Nyholt D R. et al. Genomewide linkage study in 1,176 affected sister pair families identifies a significant susceptibility locus for endometriosis on chromosome 10q26. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:365–376. doi: 10.1086/432960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Treloar S A, Zhao Z Z, Le L. et al. Variants in EMX2 and PTEN do not contribute to risk of endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:587–594. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uno S, Zembutsu H, Hirasawa A. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies genetic variants in the CDKN2BAS locus associated with endometriosis in Japanese. Nat Genet. 2010;42:707–710. doi: 10.1038/ng.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fasching P A, Loehberg C R, Strissel P L. et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the aromatase gene (CYP19A1), HER2/neu status, and prognosis in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9822-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schrauder M, Frank S, Strissel P L. et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism D1853 N of the ATM gene may alter the risk for breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:873–882. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heusinger K, Loehberg C R, Haeberle L. et al. Mammographic density as a risk factor for breast cancer in a German case-control study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2011;20:1–8. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328341e2ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sauerbrei W, Schumacher M. A bootstrap resampling procedure for model building: application to the Cox regression model. Stat Med. 1992;11:2093–2109. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simon R, Altman D G. Statistical aspects of prognostic factor studies in oncology. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:979–985. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steyerberg E W, Harrell F E jr., Borsboom G J. et al. Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:774–781. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adler W, Lausen B. Bootstrap estimated true and false positive rates and ROC curve. Comput Stat Data An. 2009;53:718–729. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hemmings R, Rivard M, Olive D L. et al. Evaluation of risk factors associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:1513–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matalliotakis I M, Cakmak H, Fragouli Y G. et al. Epidemiological characteristics in women with and without endometriosis in the Yale series. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277:389–393. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Parazzini F, Cipriani S, Bianchi S. et al. Risk factors for deep endometriosis: a comparison with pelvic and ovarian endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chapron C, Souza C, de Ziegler D. et al. Smoking habits of 411 women with histologically proven endometriosis and 567 unaffected women. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2353–2355. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Missmer S A, Hankinson S E, Spiegelman D. et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784–796. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zimmermann A, Brandes I, Babitsch B. Information needs of women with endometriosis within the scope of healthcare provision. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2010;70:568–573. [Google Scholar]