Abstract

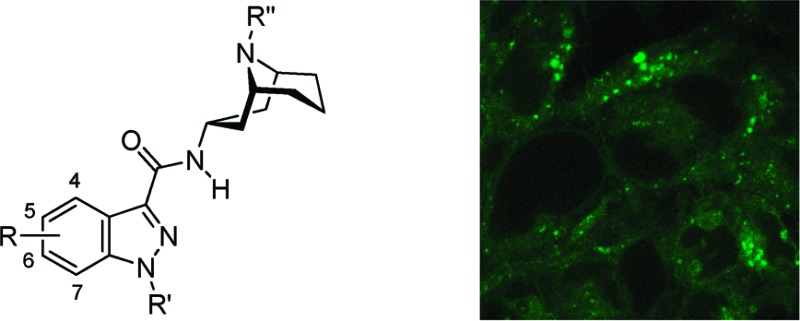

This report describes the synthesis and biological characterization of novel granisetron derivatives that are antagonists of the human serotonin (5-HT3A) receptor. Some of these substituted granisetron derivatives showed low nanomolar binding affinity and allowed the identification of positions on the granisetron core that might be used as attachment points for biophysical tags. A BODIPY fluorophore was appended to one such position and specifically bound to 5-HT3A receptors in mammalian cells.

Introduction

The serotonin (5-HTa) type 3 receptor (5-HT3R) is a ligand-gated ion channel that is responsible for rapid transmission of nerve impulses at synapses of the central and peripheral nervous system.1 It is a member of the Cys-loop family, which also includes nicotinic acetylcholine (nACh), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAA), and glycine receptors. These proteins consist of five pseudosymmetrically arranged subunits. Each subunit comprises a large extracellular N-terminal domain that is responsible for agonist binding, four transmembrane domains (M1−M4) that surround a central ion conducting pore, and a large intracellular loop between M3 and M4 that influences channel conductance and mediates the actions of intracellular messengers.

The 5-HT3R is an attractive therapeutic target. Its antagonists are used to control chemotherapy-induced, radiotherapy-induced, and postoperative nausea and vomiting and for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.2 There is some evidence that 5-HT3R antagonists might also be useful for treatment of psychiatric and neurological disorders such as anxiety, drug dependence, depression, bulimia nervosa, schizophrenia, and cognitive dysfunction.3 Another potentially interesting widespread application is their capacity to reduce pain in certain conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, and migraine.4

Structural insight of Cys-loop receptors has been gained from high resolution structures of homologous acetylcholine binding proteins (AChBPs),5 engineered nAChR subunits,6 bacterial receptors,7 and the cryoelectron microscopy data of the nAChR.8 This has allowed the construction of 5-HT3R homology models.9−12 However, such models may be too inaccurate to be useful for rational structure-based drug design and often require labor-intensive validation by experimental methods (i.e., receptor mutagenesis). Furthermore, despite structural information and homology modeling, the exact mechanism that couples agonist binding to channel opening in Cys-loop receptors is still poorly understood and cannot be elucidated by static high resolution structures alone.

Using high-affinity biophysical probes to investigate the structure and function of ligand-gated ion channels is a complementary strategy to traditional biological approaches such as radioligand binding and electrophysiology. In addition, such molecular probes, for example, utilizing fluorescent ligands as an alternative to radioligand binding or immunolabeling, can be used for assays that target specific ligand-gated ion channels.

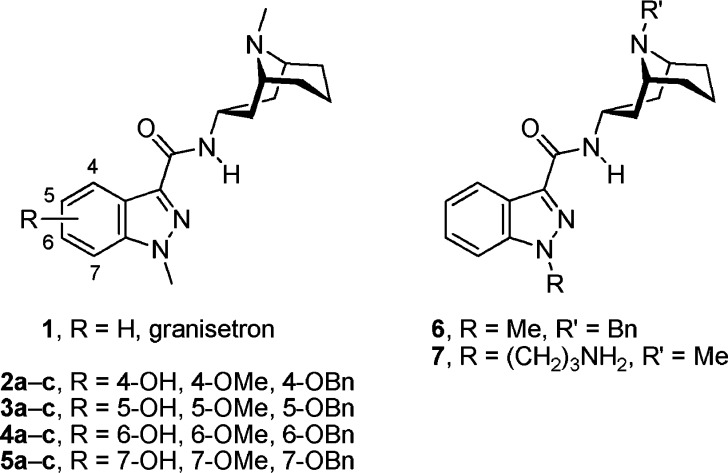

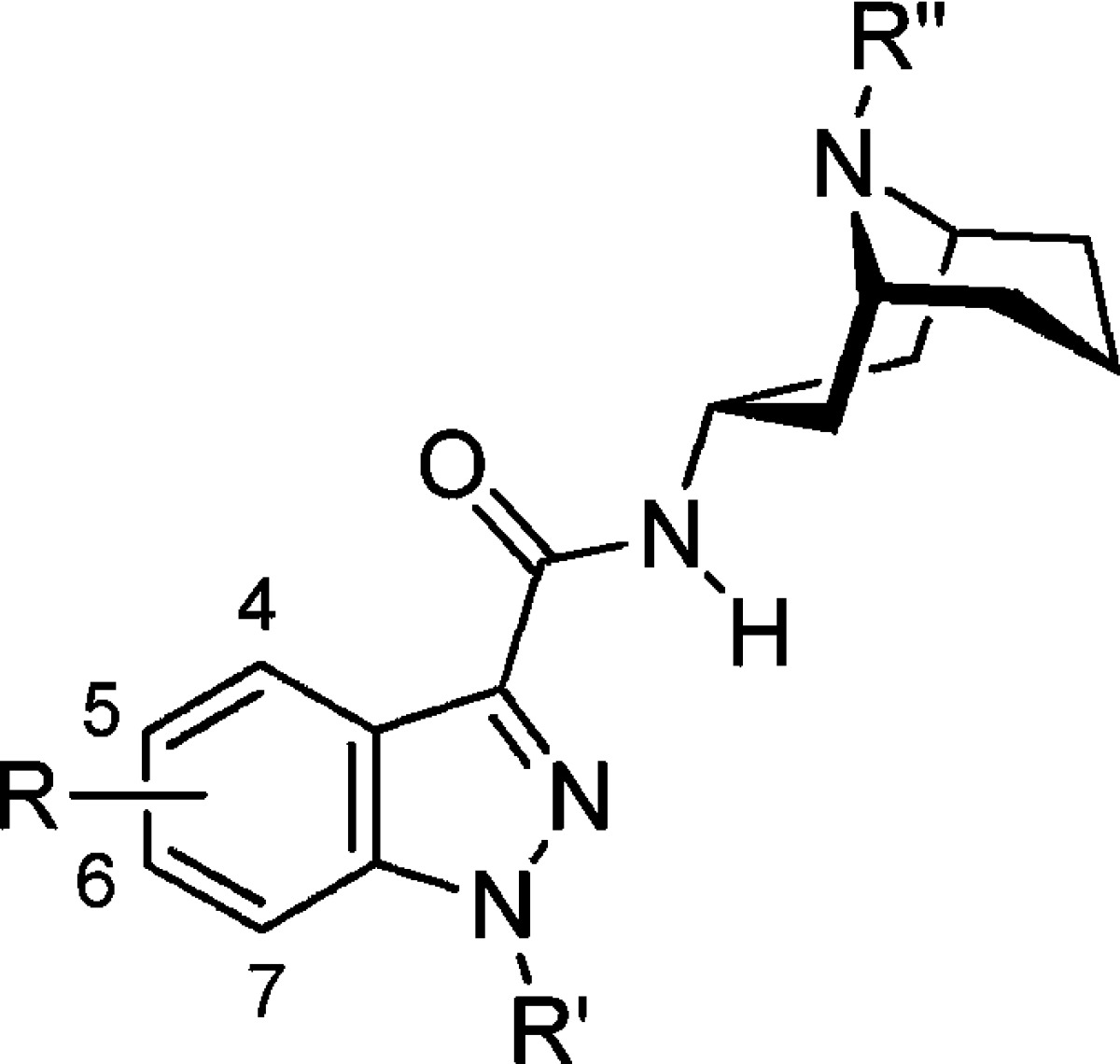

The aim of the present study was to identify tethering positions for potentially bulky biophysical tags on the high-affinity 5-HT3R antagonist granisetron13 (1, Chart 1). Because of the lack of granisetron structure−activity data in the public domain, we substituted every synthetically possible position with differently sized functional groups on the granisetron core, which yielded 14 different granisetron derivatives (Chart 1).

Chart 1. Reference and Title Compounds.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

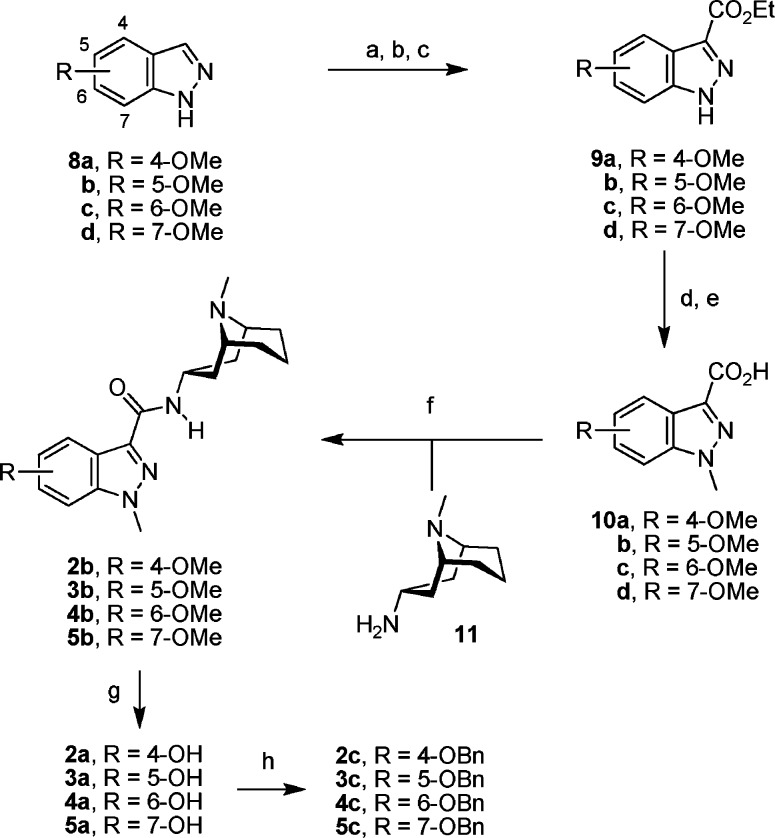

The synthesis of 2−5 is shown in Scheme 1, and it was accomplished starting from indazoles 8a−d which were prepared according to literature methods.14,15 A SEM protecting group was selectively attached to N-2 of the indazoles which was followed by a SEM-directed C-3 lithiation and subsequent reaction with an ester group donor.16 Protecting group cleavage, N-1 methylation, and subsequent ester hydrolysis furnished indazole carboxylic acids 10a−d which were coupled with bicyclic amine 11(17) to yield amides 2b−5b.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 2−5.

Reagents and conditions: (a) cHex2NMe, SEM-Cl, THF, room temp, 65−88%; (b) nBuLi, THF, −78 °C, CNCO2Et, 66−75%; (c) 2 M HCl, EtOH, room temp, 76−98%; (d) KOtBu, THF, 0 °C, MeI, room temp, 78−95%; (e) 2 M NaOH, MeOH, room temp, 97−99%; (f) DCC, HOBt, 11, 4:1 CH2Cl2/DMF, room temp, 85−94%; (g) [Me3NH][Al2Cl7], CH2Cl2, reflux, or BBr3, CH2Cl2, room temp, or NaSEt, DMF, 110 °C, 84−93%; (h) BnBr, Na2CO3, acetone, room temp, 63−94%.

The aromatic methoxy ethers were cleaved using either an excess of BBr3 in CH2Cl2 or NaSEt in hot DMF. However, no product was obtained when these methods were used for the 7-methoxy derivative 5b. Instead, when the latter compound was treated with a chloroaluminate ionic liquid18 in refluxing CH2Cl2, the desired cleavage product 5a was successfully produced in good yield (86%). Finally, hydroxyindazoles 2a−5a were alkylated under basic conditions to give benzyl ethers 2c−5c.

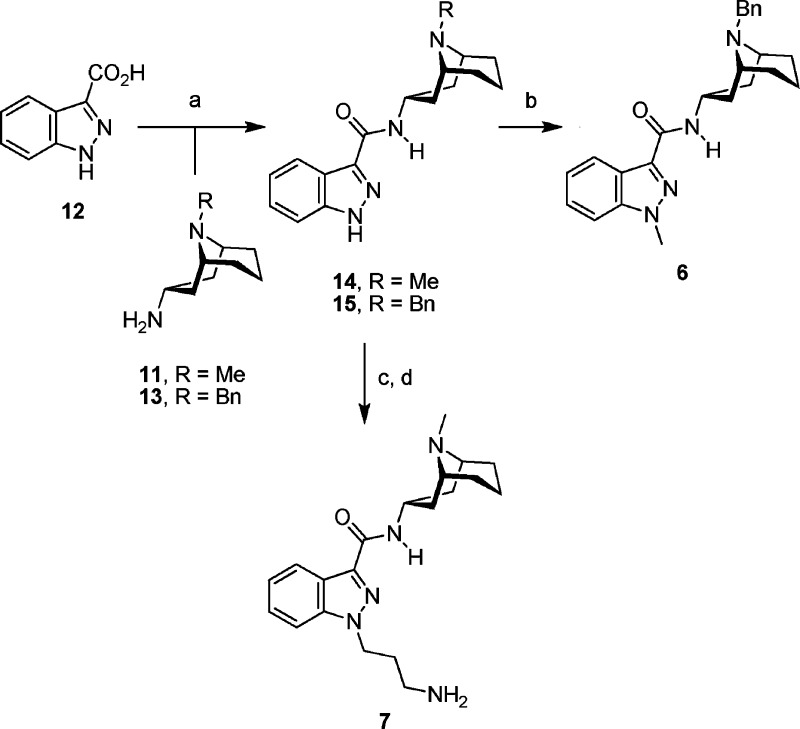

The synthesis of 6 and 7 started from commercially available 1H-indazole-3-carboxylic acid (12, Scheme 2). Coupling with bicyclic amines 11 and 13 afforded amides 14 and 15. The amine 13 was synthesized from the corresponding bicyclic ketone, 9-benzyl-9-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-3-one,19 using an oxime formation and reduction sequence as described for 11 in ref (17). Amide 15 was methylated at N-1 to yield granisetron derivative 6. Alkylation of amide 14 with 3-(Boc-amino)propyl bromide followed by deprotection under acidic conditions furnished 7.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Compounds 6 and 7.

Reagents and conditions: (a) DCC, HOBt, 11 or 13, 4:1 CH2Cl2/DMF, room temp, 81−97%. (b) For 15, R = Bn: KOtBu, THF, 0 °C; MeI, room temp, 90%. (c) For 14, R = Me: KOtBu, 5:1 THF/DMF, 0 °C, Br(CH2)3NHBoc, room temp, 78%. (d) 1.2 M HCl in MeOH, room temp, 98%.

The granatane (9-methyl-9-azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane) moiety of the synthesized granisetron derivatives 2−7 adopts a boat−chair conformation in solution, as confirmed by 1H NMR. In CD3OD, the 3-proton of the azabicycle appears as a triplet of triplets and has a coupling constant of 11.5 Hz with the 2- and 4-endo protons and a coupling constant of 6.8 Hz with the 2- and 4-exo protons (e.g., for 5a). A coupling constant of 11.0 Hz between the 2-exo and the bridgehead 1-proton was observed that is indicative of an eclipsed arrangement. Thus, the obtained 1H NMR data are in agreement with a 3-exo proton and a boat−chair conformation of the granatane.13,20

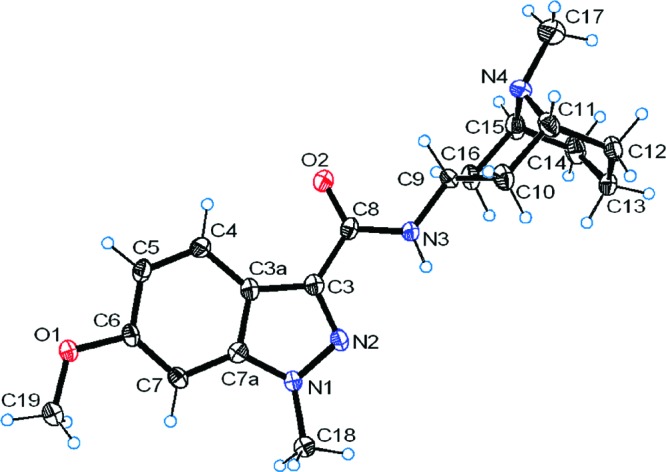

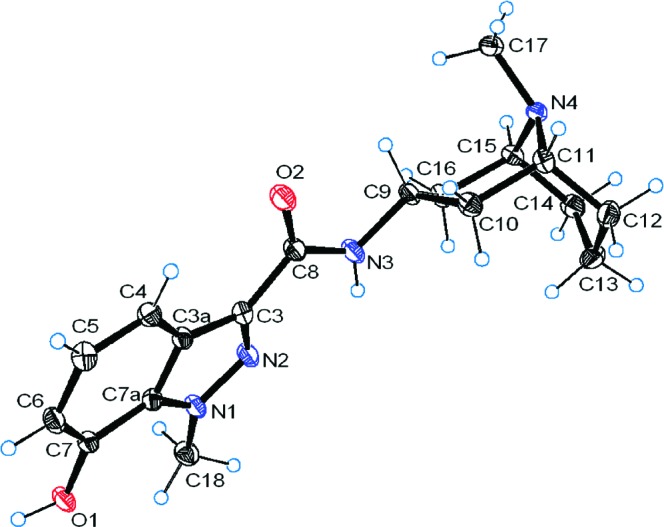

This particular structural aspect of granisetron derivatives 2−7 was further confirmed by the crystal structures of 4b and 5a (Figures 1 and 2). In both structures the indazole ring is coplanar with the amide bond and there appears to be flexibility around the bond between the amide nitrogen and the granatane. Intriguingly, the methyl group of the granatane is in an axial position with respect to the chair in 4b whereas it is equatorial in 5a. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time crystal structures of granisetron derivatives have been reported.

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of 4b. Thermal ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability.

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of 5a. Thermal ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability.

Biological Data

The affinities of granisetron derivatives 2−7 were assessed by competition with radiolabeled [3H]granisetron, an established 5-HT3AR competitive antagonist. All the compounds, except 5-substituted derivatives 3b and 3c, exhibited affinities in the nanomolar range (Table 1).

Table 1. Binding Affinities of Granisetron Derivatives 2−7 for the Human 5-HT3A Receptora.

| compd | R | R′ | R′′ |

Ki (nM) mean ± SEM |

n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | Me | Me | 1.45 ± 0.13b | 3 |

| 2a | 4-OH | Me | Me | 0.17 ± 0.09 | 5 |

| 2b | 4-OMe | Me | Me | 26.3 ± 7.4 | 4 |

| 2c | 4-OBn | Me | Me | 375 ± 61 | 4 |

| 3a | 5-OH | Me | Me | 7.3 ± 1.5 | 3 |

| 3b | 5-OMe | Me | Me | 5306 ± 209 | 4 |

| 3c | 5-OBn | Me | Me | 3029 ± 956 | 4 |

| 4a | 6-OH | Me | Me | 279 ± 27 | 4 |

| 4b | 6-OMe | Me | Me | 237 ± 51 | 3 |

| 4c | 6-OBn | Me | Me | 749 ± 183 | 4 |

| 5a | 7-OH | Me | Me | 0.67 ± 0.28 | 3 |

| 5b | 7-OMe | Me | Me | 71.1 ± 8.0 | 6 |

| 5c | 7-OBn | Me | Me | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 5 |

| 6 | H | Me | Bn | 59.3 ± 0.8 | 3 |

| 7 | H | (CH2)3NH2 | Me | 1.89 ± 0.33 | 3 |

Ki determined from competition binding with [3H]granisetron using HEK293 cell membranes stably expressing h5-HT3AR.

Reference (23).

4-Hydroxy compound 2a displayed an 8.5-fold increase in affinity for 5-HT3AR relative to 1, consistent with an H-bond here. Size is important at this location; as bulk was increased (2b and 2c), the affinity decreased ∼200-fold. However, at the 5-position size is more critical; substitution with large groups here resulted in a >1000-fold decrease in affinity (3a−c). This is consistent with previous studies that showed that the presence of a 5-chloro substituent resulted in a marked reduction in potency relative to 1.13 Substitution of the 6-position of the indazole ring was also poorly tolerated, and all the compounds in this series showed >100-fold decreases in affinities. 7-Hydroxy compound 5a exhibited a similar affinity for the 5-HT3AR when compared to 1. The data for substitutions at the 7-position show no clear pattern. Compound 5a, the major granisetron metabolite in humans,21 is interestingly as potent as granisetron.22 Affinity was decreased when the larger methoxy group was present at the 7-position but increased for the larger benzyl group, indicating that the π-system may interact with hydrophobic residues in the binding site. However, a benzyl group was less well tolerated at the bicycle 9-position: 6 exhibited a Ki of 59 nM. The aminopropyl substituent at the indazole N1-position (7) did not significantly alter the binding affinity.

Thus, the data show that the N1- and 7-positions of indazole and the 9-position of the granatane of granisetron are the most tolerant regarding substitution. This is in agreement with established pharmacophore models,24,25 and modifications of the regions we have identified have previously been well tolerated in structurally similar ligands, in particular the position occupied by groups located at a position similar to that of N1 of granisetron.26−29 Given the tolerance of the N1-position to addition of the aminopropyl linker, we consider this location the most appropriate to attach large biophysical tags.

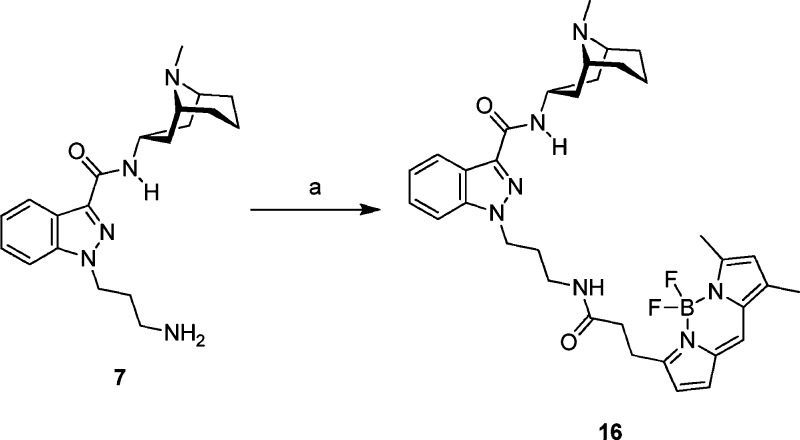

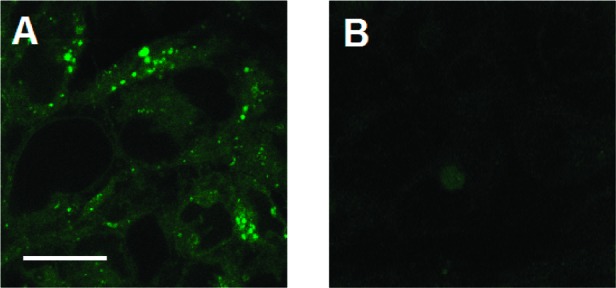

To confirm the validity of this hypothesis, we attached a BODIPY FL fluorophore at this position (Scheme 3) to create fluorescent analogue 16 (BFL-GR). Ki data show that 16 binds with high affinity to 5-HT3AR (Ki = 2.80 ± 0.72 nM, n = 3) and can be visualized in HEK293 cells expressing 5-HT3AR (Figure 3). Similar images have previously been obtained using fluorescein, rhodamine 6G, and cyanine Cy5 dyes attached via a linker at a similar position of ondansetron, another high-affinity 5-HT3AR antagonist.30

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Fluorescent Probe 16.

Reagents and conditions: (a) iPr2EtN, BODIPY FL SE, DMF, room temp, 98%.

Figure 3.

Labeling of HEK293 cells stably transfected with h5-HT3AR with 16. Cells were incubated in 10 nM 16 for 10 min with (B) or without (A) 10 μM quipazine, washed, mounted, and then observed in a confocal microscope.31 (A) Fluorescence is observed in all cells, with clusters of receptors clearly present in many cells. Unlabeled areas are nuclei. (B) Quipazine (a competitive 5-HT3R ligand) has displaced 16 from its binding sites, leaving only weak autofluorescence. Scale bar represents 20 μm.

Conclusion

In summary, several novel derivatives of granisetron (1) have been discovered. Some derivatives have high affinities for the human 5-HT3AR, and most notably derivatives 2a, 5a, 5c, and 7 equal or exceed the affinity measured for 1. The data of our systematic structure−activity study show that substitution at three positions of granisetron are well tolerated and that large functional biophysical tags can be attached at the N1-position.

Experimental Section

General

Chemicals and solvents were either purchased from commercial suppliers or purified by standard techniques. All experiments involving air-sensitive reagents were performed under an inert atmosphere in oven-dried glassware. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out on Merck silica gel 60 F254 plates, and compounds were visualized by irradiating with UV light, by exposing to I2 vapors, and/or by staining with cerium molybdate stain (Hanessian’s stain) followed by heating. Flash chromatography was carried out using Matrex silica gel 60 unless otherwise stated. Infrared spectra were recorded neat on a Nicolet AVATAR 320 FT-IR spectrometer. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DPX-300, DPX-400, and DRX-500. The chemical shifts are reported in δ (ppm), and the residual signal of the solvent was used as the internal standard. High resolution mass spectra were obtained using electrospray ionization mass (MS-ESI) technique on a Bruker MicroTOF instrument. Purity was determined by elemental analysis and/or HPLC; purity of key target compounds was ≥95%.

1-(3-Aminopropyl)-N-[(3-endo)-9-methyl-9-azabicyclo-[3.3.1]non-3-yl]-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide Dihydrochloride (7·2HCl)

Compound 14 (0.3 g, 1.0 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DMF/THF (1:5, 10 mL), cooled to 0 °C, and stirred for 5 min. Then a solution of KOtBu (0.135 g, 1.1 mmol) in anhydrous THF (2 mL) was added dropwise at 0 °C and stirred for 15 min, followed by the addition of a solution of tert-butyl N-(3-bromopropyl)carbamate (0.27 g, 1.2 mmol) in anhydrous THF (2 mL). The mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 10 h. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC. The solvents were removed under vacuo, and the residue was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic phases were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated to give the crude product. The crude product was further purified by crystallization (CH2Cl2/Et2O) to afford the carbamate (0.36 g, 0.79 mmol, 78%) as a white solid: mp 156−158 °C; Rf = 0.23 (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 7:3); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 1.14−1.17 (m, 3H), 1.45 (s, 9H), 1.54−1.65 (m, 3H), 2.02−2.21 (m, 4H), 2.44−2.52 (m, 2H), 2.55 (s, 3H), 3.11−3.14 (m, 4H), 4.54 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 4.60 (tt, J = 6.6 Hz, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.25 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz) δ 15.1, 25.7, 28.8, 33.3, 34.8, 38.8, 40.7, 41.6, 47.7, 52.8, 110.9, 123.2, 123.6, 124.0, 128.0, 137.5, 142.5, 166.8; IR (neat) 3352, 3349, 2928, 1684, 1641, 1533, 1245, 1172, 1027, 748 cm−1; HRMS-ESI(+) m/z calcd for C25H38N5O3 456.2975 [M + H]+, found 456.2990 [M + H]+. Anal. Calcd for C25H37N5O3: C 65.91%, H 8.19%, N 15.37%. Found C 65.52%, H 8.27%, N 15.04%.

To a solution of carbamate (0.16 g, 0.35 mmol) in MeOH (8 mL) was added dropwise a solution of 1.2 M HCl in MeOH (10 mL) and stirred for 12 h at room temperature. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC, and the solvents were removed in vacuo and 3 times coevaporated with toluene to get the crude product. The crude product was further purified by crystallization (CH2Cl2/Et2O) to afford 7·2HCl (0.15 g, 0.34 mmol, 98%) as a white solid: mp 296−298 °C; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 1.58−1.71 (m, 3H), 1.90−2.10 (m, 3H), 2.21−2.39 (m, 4H), 2.55−2.71 (m, 2H), 2.96−3.01 (m, 5H), 3.74 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 2H), 4.61−4.70 (m, 3H), 7.30 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.22 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz) δ 15.2, 26.7, 31.1, 34.6, 40.9, 41.0, 41.9, 49.7, 57.8, 113.4, 125.6, 126.6, 127.1, 131.0, 137.5, 144.9, 166.8; IR (neat) 2884, 2749, 2676, 1630, 1553, 1208, 745 cm−1; HRMS-ESI(+) m/z calcd for C20H30N5O 356.2450 [M − 2HCl + H]+, found 356.2445 [M − 2HCl + H]+. Anal. Calcd for C20H31Cl2N5O: C 56.07%, H 7.29%, N 16.35%, Cl 16.55%. Found C 55.21%, H 7.35%, N 16.00%, Cl 16.31%.

BFL-GR (16)

To a solution of amine hydrochloride 7·2HCl (9 mg, 0.021 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (0.5 mL) was added iPr2EtN (5.4 mg, 0.042 mmol) and stirred for 10 min. Then a solution of BODIPY FL SE (5 mg, 0.012 mmol) in DMF (1 mL) was added to the mixture and stirred at room temperature for 3.5 h. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC. The DMF was removed in vacuo and the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (CH2Cl2 and then CH2Cl2/MeOH/Et3N, 96:3:1) to afford 16 (7.9 mg, 0.012 mmol, 98%) as an orange solid: mp 190−192 °C (dec); Rf = 0.42 (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 7:3); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ 1.07−1.18 (m, 3H), 1.40−1.59 (m, 4H), 1.88−2.05 (m, 6H), 2.15 (s, 3H), 2.32−2.40 (m, 4H), 2.48−2.52 (m, 5H), 3.08−3.16 (m, 4H), 4.37 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 4.47 (tt, J = 6.7 Hz, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 6.10 (s, 1H), 6.23 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.33 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz) δ 11.2, 14.6, 15.3, 25.6, 33.0, 36.2, 37.8, 40.4, 41.1, 47.6, 53.2, 110.9, 117.7, 123.0, 123.8, 125.8, 128.1, 129.6, 138.3, 139.6, 140.5, 145.2, 149.3, 164.5, 174.8; IR (neat) 2921, 1605, 1488, 1245, 1132, 1056, 974, 734 cm−1; HRMS-ESI(+) m/z calcd for C34H43BF2N7O2 630.3539 [M + H]+, found 630.3526 [M + H]+; UV/vis/Fluo (MeOH) λmax abs = 506 nm, λmax emiss = 514 nm.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the EPSRC (EP/E042139/1) and the Wellcome Trust (081925/Z/07/Z, A.J.T. and S.C.R.L.) for financial support. S.C.R.L. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Basic Biomedical Science.

Supporting Information Available

Synthesis details and spectral data for compounds other than 7 and 16, HPLC purity assessment for all target compounds, CIF files of 4b and 5a, experimental details for competition binding, and Ki determination. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 5-HT, serotonin; 5-HT3R, 5-HT3 receptor; AChBP, acetylcholine binding protein; nAChR, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; Boc, tert-butoxycarbonyl; CD3OD, tetradeuteriomethanol; DCC, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide; DMF, N,N-dimethylformamide; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; HOBt, 1-hydroxybenzotriazole; SEM, 2-(trimethylsilyl)ethoxymethyl; THF, tetrahydrofuran.

Supplementary Material

References

- Reeves D. C.; Lummis S. C. R. The molecular basis of the structure and function of the 5-HT3 receptor: a model ligand-gated ion channel. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2002, 19, 11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A. J.; Lummis S. C. R. The 5-HT3 receptor as a therapeutic target. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2007, 11, 527–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenshaw A. J.; Silverstone P. H. The non-antiemetic uses of serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutic applications. Drugs 1997, 53, 20–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Färber L.; Drechsler S.; Ladenburger S.; Gschaidmeier H.; Fischer W. The neuronal 5-HT3 receptor network after 20 years of research. Evolving concepts in management of pain and inflammation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 560, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brejc K.; van Dijk W. J.; Klaassen R. V.; Schuurmans M.; van der Oost J.; Smit A. B.; Sixma T. K. Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature 2001, 411, 269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellisanti C. D.; Yao Y.; Stroud J. C.; Wang Z.-Z.; Chen L. Crystal structure of the extracellular domain of nAChR α1 bound to α-bungarotoxin at 1.94 Å resolution. Nat. Neurosci. 2007, 10, 953–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilf R. J. C.; Dutzler R. X-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature 2008, 452, 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N. Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 346, 967–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves D. C.; Sayed M. F. R.; Chau P.-L.; Price K. L.; Lummis S. C. R. Prediction of 5-HT3 receptor agonist-binding residues using homology modeling. Biophys. J. 2003, 84, 2338–2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A. J.; Price K. L.; Reeves D. C.; Ling Chan S.; Chau P.-L.; Lummis S. C. R. Locating an antagonist in the 5-HT3 receptor binding site using modeling and radioligand binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 20476–20482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi P. R.; Suryanarayanan A.; Hazai E.; Schulte M. K.; Maksay G.; Bikadi Z. Interactions of granisetron with an agonist-free 5-HT3A receptor model. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 1099–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D.; White M. M. Spatial orientation of the antagonist granisetron in the ligand-binding site of the 5-HT3 receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 68, 365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez J.; Fake C. S.; Joiner G. F.; Joiner K. A.; King F. D.; Miner W. D.; Sanger G. J. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT3) receptor antagonists. 1. Indazole and indolizine-3-carboxylic acid derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 1990, 33, 1924–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann P.; Collot V.; Hommet Y.; Gsell W.; Dauphin F.; Sopkova J.; MacKenzi E. T.; Duval D.; Boulouard M.; Rault S. Inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase by 7-methoxyindazole and related substituted indazoles. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 1153–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada I.; Maeno K.; Kazuta K.-i.; Kubota H.; Kimizuka T.; Kimura Y.; Hatanaka K.-i.; Naitou Y.; Wanibuchi F.; Sakamoto S.; Tsukamoto S.-i. Synthesis and structure−activity relationships of a series of substituted 2-(1H-furo[2,3-g]indazol-1-yl)ethylamine derivatives as 5-HT2C receptor agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 1966–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo G.; Chen L.; Dubowchik G. Regioselective protection at N-2 and derivatisation at C-3 of indazoles. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 5392–5395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donatsch P.; Engel G.; Hügi B.; Richardson B. P.; Stadler P. A.; Breuleux G.. Method of Inducing a Serotonin M Receptor Antagonist Effect with N-Quinuclidinyl-benzamides. US 5,017,582, 1991.

- Kemperman G. J.; Roeters T. A.; Hilberink P. W. Cleavage of aromatic methyl ethers by chloroaluminate ionic liquid reagents. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 1681–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Dold O.; Stach K.; Schaumann W.. 3-Phenylnorgranat-2-enes. US 3,509,161, 1970.

- Fernandez M. J.; Huertas R.; Galvez E. Synthesis and structural and conformational study of some amines derived from the norgranatane system. J. Mol. Struct. 1991, 246, 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S. E.; Austin N. E.; Bloomer J. C.; Haddock R. E.; Higham F. C.; Hollis F. J.; Nash M.; Shardlow P. C.; Tasker T. C. Metabolism and disposition of 14C-granisetron in rat, dog and man after intravenous and oral dosing. Xenobiotica 1994, 24, 1119–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr H. E.; Haddock R. E.; Ramsay T. W.. Preparation of 9-Azabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane Derivatives as 5-HT3 Receptor Antagonists. WO 9,101,316, 1991.

- Hope A. G.; Peters J. A.; Brown A. M.; Lambert J. J.; Blackburn T. P. Characterization of a human 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor type A (h5-HT3R-AS) subunit stably expressed in HEK 293 cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996, 118, 1237–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parihar H. S.; Suryanarayanan A.; Ma C.; Joshi P.; Venkataraman P.; Schulte M. K.; Kirschbaum K. S. 5-HT3R binding of lerisetron: an interdisciplinary approach to drug−receptor interactions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 2133–2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A. W.; Peroutka S. J. Three-dimensional steric molecular modeling of the 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor pharmacophore. Mol. Pharmacol. 1989, 36, 505–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli A.; Gallelli A.; Manini M.; Anzini M.; Mennuni L.; Makovec F.; Menziani M. C.; Alcaro S.; Ortuso F.; Vomero S. Further studies on the interaction of the 5-hydroxytryptamine3 (5-HT3) receptor with arylpiperazine ligands. Development of a new 5-HT3 receptor ligand showing potent acetylcholinesterase inhibitory properties. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3564–3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli A.; Anzini M.; Vomero S.; Mennuni L.; Makovec F.; Doucet E.; Hamon M.; Menziani M. C.; De Benedetti P. G.; Giorgi G.; Ghelardini C.; Collina S. Novel potent 5-HT3 receptor ligands based on the pyrrolidone structure: synthesis, biological evaluation, and computational rationalization of the ligand−receptor interaction modalities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002, 10, 779–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. D.; Miller A. B.; Berger J.; Repke D. B.; Weinhardt K. K.; Kowalczyk B. A.; Eglen R. M.; Bonhaus D. W.; Lee C.-H.; Michel A. D.; Smith W. L.; Wong E. H. F. 2-(Quinuclidin-3-yl)pyrido[4,3-b]indol-1-ones and isoquinolin-1-ones. Potent conformationally restricted 5-HT3 receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 2645–2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tairi A.-P.; Hovius R.; Pick H.; Blasey H.; Bernard A.; Surprenant A.; Lundström K.; Vogel H. Ligand binding to the serotonin 5HT3 receptor studied with a novel fluorescent ligand. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 15850–15864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohland T.; Friedrich K.; Hovius R.; Vogel H. Study of ligand−receptor interactions by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy with different fluorophores: evidence that the homopentameric 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3As receptor binds only one ligand. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 8671–8681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spier A. D.; Wotherspoon G.; Nayak S. V.; Nichols R. A.; Priestley J. V.; Lummis S. C. R. Antibodies against the extracellular domain of the 5-HT3 receptor label both native and recombinant receptors. Mol. Brain Res. 1999, 71, 369. (Erratum). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.