Abstract

Objective

This study examined the role of community in understanding Latino adults’ (18–64 years of age) use of community mental health services.

Methods

Service utilization data from the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health were analyzed from 2003 in two service provider areas. Demographic data, including foreign-born status, language, education, and income for the Latino population, were obtained from the 2000 U.S. Census. The study sample consisted of 4,133 consumers of mental health services in 413 census tracts from an established immigrant community and 4,156 consumers of mental health services in 204 census tracts from a recent immigrant community. Negative binomial regression analyses were conducted to examine associations between locales, community characteristics, and use of services.

Results

Community of residence and foreign-born status were significantly associated with Latinos’ service use. Latinos from the established immigrant community were more likely to use services than Latinos from the recent immigrant community. Across both communities, census tracts with a higher percentage of foreign-born noncitizen residents showed lower service use. Within the established immigrant community, as income levels increased there was little change in utilization. In contrast, in the recent immigrant community, as income levels increased utilization rates increased as well (β=.001, p<.001).

Conclusions

The findings point out the importance of locale and community determinants in understanding Latinos’ use of public mental health services.

National (1) and local (2) epidemiological studies have reported that Latino adults with diagnosable mental disorders use mental health services less than white and African-American populations. Studies based on clinical populations also have documented lower rates of service use by Latinos (3). The different methods used across community and clinical populations indicate that in regard to need and representation in the community, Latinos are using fewer services than other ethnic-racial groups. Because of these low levels of use, there has been a push to identify barriers to mental health care (4) and improve access to services (5).

Past research has examined individual-level characteristics as they relate to service use but has focused less on community-level variables. Some of the individual factors that increase the likelihood of use among Latinos include English language proficiency (3), U.S. birthplace, and higher education levels (with income levels having a curvilinear relationship, with higher use of services at the low and high ends of income distributions) (2). Few studies have assessed the influence of specific communities above and beyond individual-level predictors (1). Although individual factors play an important role in mental health service utilization, ecological and social factors that vary across unique local social worlds (6,7) also likely contribute to service use.

Two Los Angeles area communities

To examine the relationship of locale, community determinants, and service utilization, we compared Latinos’ use of mental health services in two service provider areas that are part of the same system of care within the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health (LACDMH). One area is home to a relatively established immigrant Latino community and spans the northwestern portion of Los Angeles County, whereas the other is populated by a more recent influx of immigrants and spans the southern portions of the county. We selected these communities with different histories of Latino immigration and settlement because they represent different local social worlds and levels of integration by the Latino community.

The Latino immigration in the established community dates back to the late 1800s. A large influx of Latinos entered the community beginning in the late 1950s, a trend that continues today. The original agricultural roots have given way to a suburban area supported largely by manufacturing plants that attract Latino immigrants to work and live in the area (8). We hypothesized that the long-standing presence of Latinos in the established immigrant community has contributed to the system of care’s responsiveness to Latinos’ mental health needs.

In contrast, the recent immigrant community has historically been a predominantly blue-collar African-American community with a heavy industrial employment base. Since 1980, the area consisting of the recent immigrant community has seen a rapid increase in its Latino population (from 23% in 1980 to 53% in 2000) while the historically African-American population has declined (from 64% in 1980 to 35% in 2000) (9,10). We further hypothesized that the lack of an established presence of Latinos in the recent immigrant community, despite their recent influx into the area, is associated with less penetration into the mental health system by its Latino residents.

Community-level factors associated with barriers to care

As noted above, foreign-born status, language use, education, and income are among the individual-level variables associated with lower levels of service use among Latinos. We were interested in these factors, but we assessed them at the community level, because they suggest the possibility of barriers to service. Individual-level variables shed light on the characteristics of individuals that influence use but disregard the interaction of individuals with their communities. Such interaction may encourage or discourage appropriate use of mental health services. Communities with similar demographic characteristics and thus similar levels of assumed need may differ in use of services as a result of the mental health system, community, or cultural factors that facilitate or impede penetration into the mental health service system (11). By focusing on places it may be possible to identify community factors that are less likely to be revealed when focusing on individuals (12).

Our first aim was to assess whether service use varied by community. We hypothesized that Latinos would utilize services at a lower rate in the recent immigrant community than in the established immigrant community. Second, we examined the role of specific community factors as they relate to Latinos’ service use, specifically foreign-born population, language, education level, and income, all community factors associated with service utilization (1–5). Finally, we explored whether the community moderated each factor’s relationship with service use.

Methods

Study population and data

The study sample consisted of 4,133 service users in 413 census tracts from the established immigrant community and 4,156 service users in 204 census tracts from the recent immigrant community. Service utilization data were obtained from the LACDMH for the 2003 calendar year. The two communities correspond with two service provider areas determined by LACDMH.

To assess use of services among the target population, we assessed service use relative to the number of people in poverty per census tract. The established immigrant community had 80,689 Latino adults in poverty, whereas the recent immigrant community had 96,107 adults in poverty. Demographic data (foreign-born noncitizen population, Spanish language levels, education, income, and population in poverty) were obtained from the 2000 U.S. Census Factfinder database (factfinder.census.gov) by generating custom tables of these variables for Latino adults in the census tracts within the two communities of interest. The study received institutional review board approval from both the University of California, Los Angeles, and LACDMH.

Service use

Our dependent variable was the number of Latinos utilizing mental health services. This variable was operationalized in the model with unduplicated counts of Latino adults (ages 18–64) who used an LACDMH service provider in 2003 and who resided in census tracts within the two service provider areas of interest. The counts of users were aggregated into census tracts within the two communities. The Latino adult population (ages 18–64) in poverty in a given census tract served as the exposure variable, meaning that utilization was analyzed relative to the number of people in poverty per census tract. The primary consumers of LACDMH services are persons who meet requirements for Medi-Cal (California Medicaid) or indigent status. Poverty status is a major component of Medi-Cal requirements. Legal immigration status is typically required, although some clinics will see and treat consumers who are indigent, which could include undocumented immigrants. We examined the number of adults using services in census tracts relative to the number of Latino adults in poverty in each census tract. Doing so allowed us to consider use relative to the size of the target population.

Community determinants

The independent variables were community (recent immigrant community or established immigrant community), foreign-born residents who were noncitizens (percentage of Latinos per census tract who were not U.S. born and had not obtained citizenship), Spanish language (percentage of primarily Spanish speakers per census tract who reported speaking Spanish at home and speaking little to no English), education (percentage of Latinos with less than ninth grade education per census tract), and income (Latino per capita income per census tract for 1999). The identification of persons as foreign-born noncitizens and primarily Spanish speaking was based on a self-report measure used by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2000. We tested the independent effects of each predictor as well as the interactions of foreign-born noncitizen status, Spanish language, education, and income with community to determine differential effects by community.

Analyses

The most appropriate methods for the analysis of count data were Poisson regression and negative binomial regression (13). Negative binomial regression is a form of the Poisson regression model and is appropriate when data are overdispersed (that is, with variance greater than the mean). Overdispersion can produce underestimates of standard errors in Poisson models, leading to overstatement of statistical significance (14). In our case, the dependent variable was positively skewed, indicating that most census tracts had low rates of use and therefore that a normal distribution was not achieved. The fact that the confidence intervals for alphas for each model did not include zero (necessary for Poisson) confirmed the appropriateness of the negative binomial regression model in our analysis (15).

Results

Characteristics of two communities

Relative to the established community, the recent immigrant community census tracts had higher proportions of foreign-born noncitizen residents (recent immigrants, 43%; established immigrants, 30%), persons who spoke primarily Spanish (recent immigrants, 45%; established immigrants, 23%), and persons with less than a ninth grade education (recent immigrants, 50%; established immigrants, 24%). In addition, the recent immigrant community had lower Latino per capita annual income than the established immigrant community (recent immigrants, $8,257; established immigrants, $17,151) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Community-level determinants to predict utilization of mental health services in two Latino communities in Los Angeles County

| Recent immigrant community census tracts (N=413) |

Established immigrant community census tracts (N=204) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determinant | M | SD | M | SD |

| Foreign-born noncitizen residents (%) | 30.0 | 15.0 | 43.4 | 8.9 |

| Spanish speakers (%) | 23.3 | 16.0 | 45.3 | 11.0 |

| Less than 9th grade education (%) | 23.5 | 16.3 | 49.9 | 11.4 |

| Per capita income | $17,151 | $9,898 | $8,257 | $3,289 |

Community-level determinants of Latinos’ utilization of services

Using Stata 9 (16), we tested a negative binomial regression model of Latinos’ mental health service use by examining use in relation to community (established immigrant and recent immigrant communities), determinants of use (proportion of foreign-born noncitizen residents, proportion of Spanish speakers, education level, and per capita income), and the interactions of community with the determinants. The interactions of community with education and community with Spanish language were not significant; we therefore removed them from the final model. Overall, the model significantly predicted community mental health service utilization for the Latino adult population in poverty (Wald χ2=306.70, df=7, p<.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Negative binomial regression model to predict utilization of mental health services in two Latino communities in Los Angeles Countya

| Independent variable | β | SE | z | p>|z|b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community | −1.36 | .35 | −3.89 | .001 |

| Foreign-born noncitizen residents | −2.88 | .40 | −7.26 | .001 |

| Spanish speakers | −.45 | .36 | −1.24 | .216 |

| Less than 9th grade education | −.41 | .31 | −1.31 | .190 |

| Per capita income | .01 | .01 | −.54 | .592 |

| Community × foreign-born | 1.66 | .58 | 2.85 | .004 |

| Community × income | .01 | .01 | −7.51 | .001 |

Population in poverty was used as the exposure variable (relative to size of population in poverty).

p value for z test

Within this model, we found that both the community and the proportion of foreign-born noncitizen residents significantly predicted service use. Latino adults utilized services at significantly higher rates in the established immigrant community than in the recent immigrant community (β=–1.36, p=.001). Controlling for other variables in the model, we estimated the predicted rates of utilization in the two communities to be 8.15% (established immigrant) and 5.23% (recent immigrant) of Latino adults in poverty. Overall, as the proportion of foreign-born noncitizen residents increased in census tracts, less service use was observed (β=–2.88, p<.001). The census tracts’ proportion of Spanish speakers, percentage of Latinos with less than a ninth grade education, and per capita income of Latinos were not significantly associated with service utilization for the sample (Table 2).

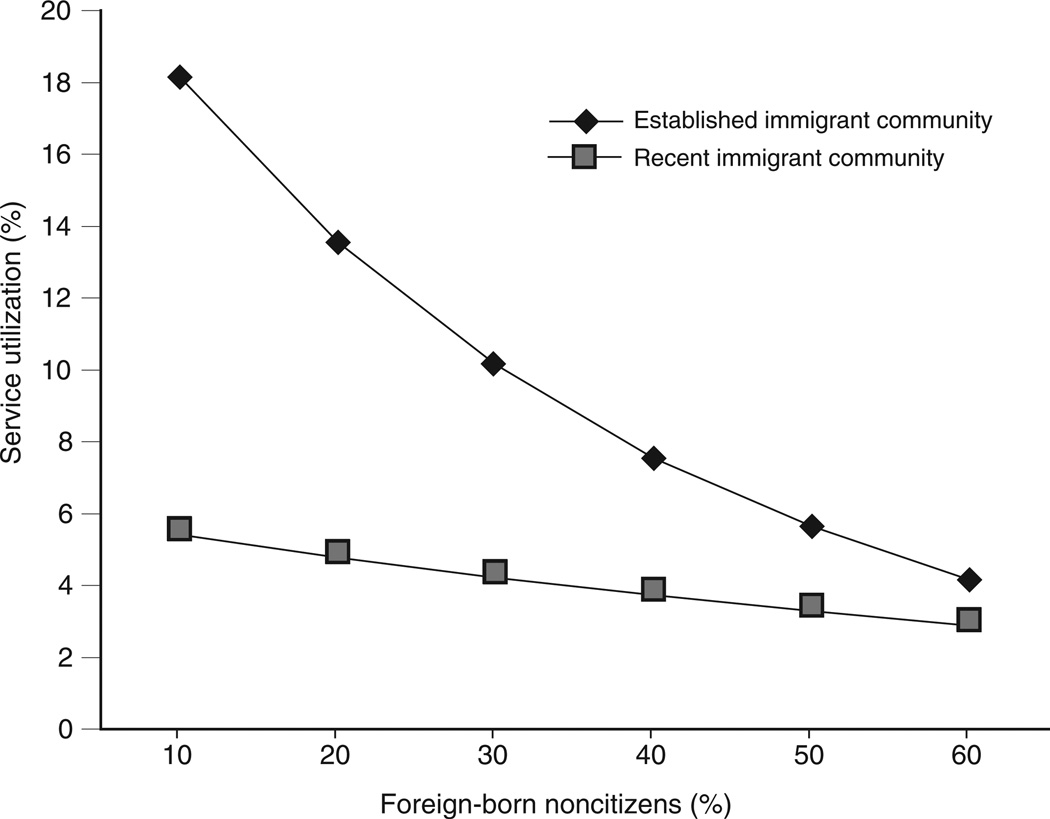

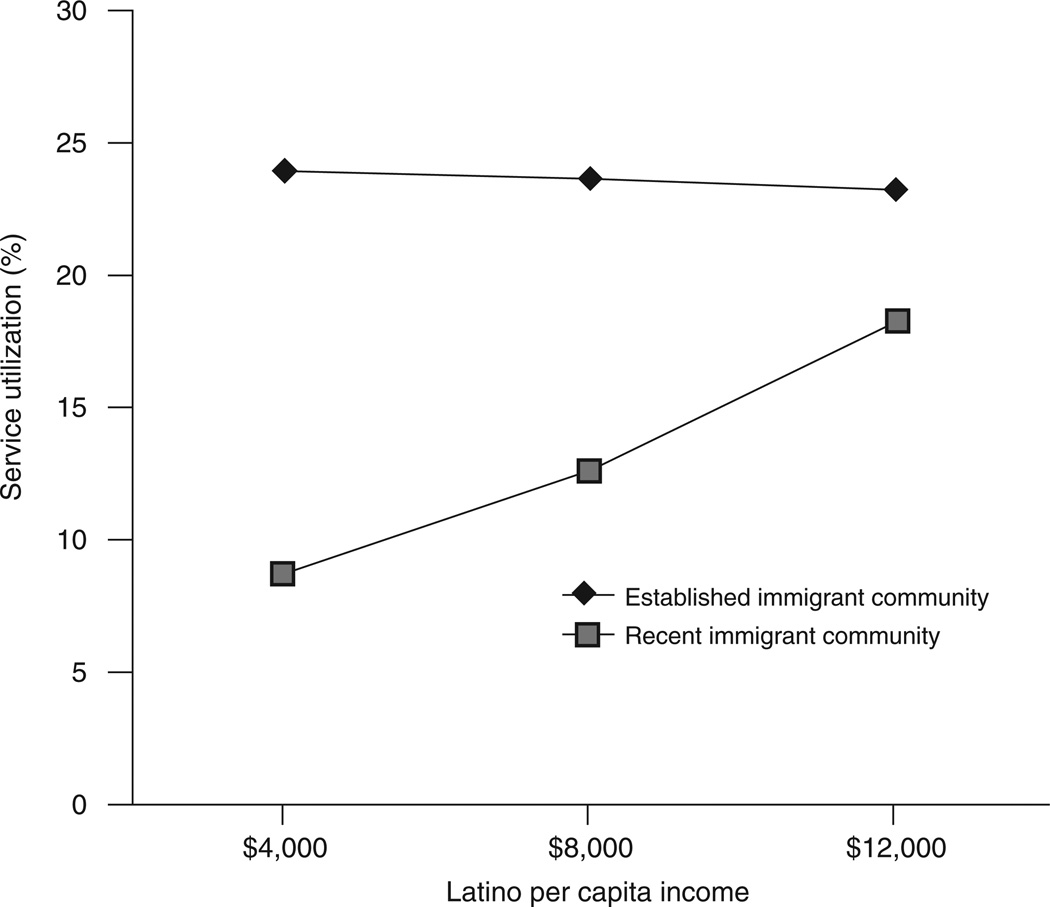

The interactions of community with foreign-born status (β=1.66, p=.004) and with income (β=.001, p<.001) also proved significant. As illustrated in Figure 1, the proportion of foreign-born noncitizen residents was more strongly associated with Latino service use in the established immigrant community than in the recent immigrant community. These findings point out that the utilization of services was more reactive to the proportion of foreign-born noncitizen residents in the established immigrant community than in the recent immigrant community. With regard to community and income, Figure 2 indicates that within the established immigrant community, as income levels increased there was little change in utilization. In contrast, in the recent immigrant community, as income levels increased utilization rates increased as well (β=.001, p<.001).

Figure 1.

Interaction of foreign-born status with community in utilization of mental health services in two Latino communities in Los Angeles County

Figure 2.

Interaction of income with community in utilization of mental health services in two Latino communities in Los Angeles County

Discussion

Latinos’ use of public mental health services can vary by community in significant ways. Although Latino service use has been shown to be low relative to need (2), differences existed between two locales within a single mental health system. Consistent with our first hypothesis, Latinos used services at higher rates in the established immigrant community compared with the recent immigrant community. An examination of specific community factors sheds some light on the possible reasons for this different rate of service use.

One community factor concerns the number of foreign-born persons in a census tract. We found that higher levels of foreign-born noncitizen residents in a census tract were related to lower use of services. Although a higher proportion of foreign-born noncitizen residents was associated with less use in both communities, the association was weaker in the recent immigrant community. Figure 1 indicates that the recent immigrant community showed low levels of use regardless of the proportion of foreign-born residents, whereas the established community had particularly low use only in the census tracts with high proportions of foreign-born residents but showed higher use than the recent immigrant community. These findings show that people living in census tracts with otherwise similar demographic characteristics (foreign-born noncitizen density) had different levels of use depending on their community of residence.

Income was another community factor that played a role in and was moderated by the community. Service use in the recent immigrant community was higher for people who lived in higher-income census tracts, whereas service use in the established immigrant community was not associated with income levels. These findings are particularly noteworthy given that community mental health services are available to all, regardless of people’s ability to pay. The near-zero association between the income level of census tracts within the established immigrant community was what one might expect, indicating that persons below the poverty level, regardless of the income level of the census tracts, used available services. However, for the recent immigrant community, the census tracts with higher income levels made greater use of services than the census tracts with lower income levels.

We consider two possible explanations for this pattern of findings—differential need and differences in social capital. Prevalence of mental disorders has been shown to be lower among foreign-born Mexican Americans than among U.S.-born Mexican Americans, suggesting that immigrant communities have a lower need for services (17). The fact that overall, census tracts indicated more foreign-born residents (43%) in the recent community than in the established community (30%) is at first look consistent with the finding of less service use in the recent immigrant community than in the established immigrant community. However, our analysis revealed lower degrees of use in the recent immigrant community when we controlled for proportions of foreign-born noncitizen residents, suggesting that differential need does not likely explain the service use differences. In addition, some aspects of the communities influenced these disparities above and beyond previously documented low use of services among immigrants.

An alternative explanation for the differential service use between communities is social capital. Communities with lower social capital may have fewer social support systems to facilitate the entry of persons with mental disorders into the mental health delivery system (11). The measured community factor that approximates social capital was per capita income per census tract. The average per capita income of the recent immigrant community’s census tract ($8,257) was less than half that of the established community ($17,151). Moreover, per capita income was differentially related to service use for the two communities. For the recent immigrant community, as the per capita income per census tract increased, so did the use of mental health services. Moreover, at higher levels of per capita income, service use began to approximate the service use within the established immigrant community. These findings are consistent with the interpretation that social capital of census tracts can facilitate service use, particularly if the community as a whole has low social capital. In contrast, for the established community in which there was much greater social capital, the role of social capital of a specific census tract may be of less importance.

The differential service use by community points out the importance of community in the interpretation of disparate findings. Latinos are not simply one monolithic community that responds similarly regardless of the sociocultural context. Although there are similarities within the group, facilitating and impeding forces in local communities also affect the likelihood of integration into the mental health service system. It is important to note that although the services within the established immigrant community appeared to do a better job in reaching communities with a larger percentage of foreign-born residents than the services within the recent immigrant community, services within both communities were reaching low numbers of persons living in the predominantly foreign-born noncitizen census tracts.

A limitation of this study is that it focused only on public mental health services and not the full range of available mental health or primary care services. Our focus on the low end of the income spectrum is also a limitation. Utilization tended to occur as a U-shaped graph, with the lowest income earners having high rates of use, middle-class earners having lower use, and higher-class earners having high rates of use (18,19). Another limitation is the possibility that the 2000 Census undercounted the number of undocumented immigrants by 10%–15% (20). If this were the case, then we underestimated disparities in utilization. Finally, we did not obtain service provider characteristics to directly address systemic factors, nor did we measure the quantity or quality of care. Future inquiry into these areas would elucidate provider characteristics that may influence use of services.

Conclusions

It is important to understand the impact of social context and locale when addressing disparities in mental health service use. The focus on ethnicity and service use tends to portray ethnic groups as monolithic entities that are static regardless of contextual factors. Alegria and colleagues (1) showed marked regional differences in utilization in the United States, and we have shown differences between two communities within the same county and service system. Community-level analyses highlight how community norms, structures, and processes affect the health and well-being of its members (11). The focus on individual-level factors runs the risk of ignoring important social structural issues that may be responsible for disparities in service use.

Identifying community-level factors can serve as an impetus for development of research and policy and for changes in resource allocation and intervention targets. Our findings could help inform the development of interventions and policies that aim to increase participation of Latinos in the mental health system. Efforts should be made to identify not only ethnic groups but also community subsamples (including high-density areas of foreignborn residents) that have the greatest need. A clear understanding of the local community picture will aid in developing focused policy solutions to disparities in health utilization and outcomes. As communities grow in size and diversity, and particularly Latino communities, it becomes necessary to track the responsiveness of community mental health services to those specific communities in most need.

Acknowledgments

The first author thanks the Ford Foundation for its support during this study. The authors also thank Olivia Celis, Lashanda Brown, and the Los Angeles Department of Mental Health for their assistance with data collection for this study.

Footnotes

disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Adrian Aguilera, Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), 1285 Franz Hall, Box 951563, Los Angeles, CA 90095 (aaguil@ucla.edu)

Steven Regeser López, Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry at UCLA

References

- 1.Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, et al. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. Gaps in service utilization by Mexican Americans with mental health problems. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:928–934. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrio C, Yamada AM, Hough RL, et al. Ethnic disparities in use of public mental health case management services among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:1264–1270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.9.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vega WA, Karno M, Alegria M, et al. Research issues for improving treatment of US Hispanics with persistent mental disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:385–394. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez SR. A research agenda to improve the accessibility and quality of mental health care for Latinos. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:1569–1573. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleinman A, Eisenberg L. Mental health in low-income countries. Nature Medicine. 1995;1:630–631. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotkin J, Ozuna E. Malibu, Calif, Economic Alliance of the San Fernando Valley. Pepperdine University School of Public Policy; 2002. The Changing Face of the San Fernando Valley. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tseng T. Malibu, Calif, Pepperdine University. Davenport Institute; 1999. Common Paths: Connecting Metropolitan Inner City Opportunities. Davenport Institute Research Report. Available at publicpolicy.pepperdine.edu/davenport-institute/reports/common-paths. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldinger R. From Ellis Island to LAX: immigrant prospects in the American city. International Migration Review. 1996;30(1):78–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snowden LR. Racial, cultural and ethnic disparities in health and mental health: toward theory and research at community levels. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;35:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-1882-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacIntyre S, MacIver S, Sooman A. Area, class, and health: should we be focusing on places or people? Journal of Social Policy. 1993;22:213–234. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner W, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:392–404. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calhoun PS, Bosworth HB, Grambow SC, et al. Medical service utilization by veterans seeking help for posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:2081–2086. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long S, Friese J. College Station, Tex. Stata Press; 2003. Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stata Statistical Software, release 7.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:771–778. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young JT. Illness behaviour: a selective review and synthesis. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2004;26:1–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2004.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snowden LR, Thomas K. Medicaid and African American outpatient mental health treatment. Mental Health Services Research. 2000;2:115–120. doi: 10.1023/a:1010161222515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiquiar D, Hanson GH. International migration, self-selection, and the distribution of wages: evidence from Mexico and the United States. Journal of Political Economy. 2005;119:239–281. [Google Scholar]