Abstract

Objectives. We examined relationships between implementation of tobacco quitline practices, levels of evidence of practices, and quitline reach and spending.

Methods. In June and July 2009, a total of 176 quitline funders and providers in the United States and Canada completed a survey on quitline practices, in particular quitline-level implementation for the reported practices. From these data, we selected and categorized evidence-based and emerging quitline practices by the strength of the evidence for each practice to increase quitline efficacy and reach.

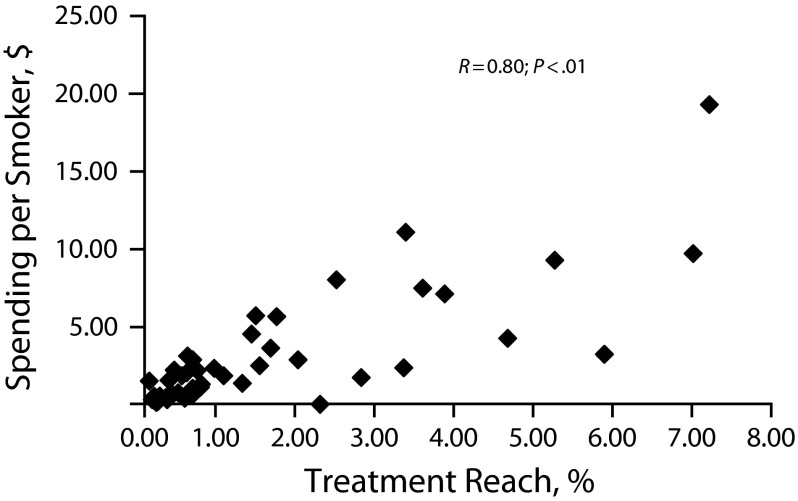

Results. The proportion of quitlines implementing each practice ranged from 3% (text messaging) to 92% (providing a multiple-call protocol). Implementation of practices showing higher levels of evidence for increasing either reach or efficacy showed moderate but significant positive correlations with both reach outcomes and spending levels. The strongest correlation was between reach outcomes and spending levels (r = 0.80; P < .01).

Conclusions. The strong relationship between quitline spending and reach reinforces the need to increase quitline funding to levels commensurate with national cessation goals.

Tobacco cessation quitlines have become part of the national infrastructure in the United States and Canada to provide population-based treatment to tobacco users.1 Quitlines serve tobacco users in all 50 US states, Washington, DC, Puerto Rico, and Guam, and in all 10 provinces and 2 territories in Canada.2 Annually, quitlines serve more than 400 000 tobacco users in the United States and more than 12 000 in Canada.2

There is considerable evidence that quitlines are effective.3,4 However, there are many treatment- and outreach-related practices that make up quitline operations, and their use can vary considerably by quitline. For example, variation between quitlines in the implementation of proactive counseling (where cessation counselors call tobacco users directly, rather than waiting for tobacco users to call the quitline) could affect treatment efficacy because proactive treatment is more effective than reactive treatment.3,5–8

To assess the range of quitline practices available and the factors that affect implementation of those practices, we conducted a multiyear survey with US and Canadian quitlines.9–11 Although 1 study has provided a descriptive overview of quitline practices, spending, and reach on the basis of data collected in 2005,12 thus far, no studies have analyzed the process for implementation of practices by quitlines in the United States and Canada. In addition, Cummins et al. did not consider the level of evidence for quitline practices.12 To make recommendations on specific practices that may increase quitline efficacy and reach, we examined both the variability of quitline practice implementation and the relationships between levels of evidence for individual practices and quitline reach and spending.

Building on the foundational study by Cummins et al.,12 we based our analysis on the primary question that they asked: To what extent were different types of practices implemented within and across quitlines? We expanded our inquiry by asking 2 additional questions: (1) What are the patterns of implementation of practices grouped by research evidence level? and (2) What is the relationship between implementation of practices (individually or grouped by research evidence level) and either spending levels for quitlines or actual treatment reach outcomes?

METHODS

The study team included the 5 authors, 7 additional researchers (6 from the University of Arizona and 1 from the University of British Columbia), and 3 North American Quitline Consortium (NAQC) staff members. The team also consulted extensively with an advisory work group consisting of 8 representatives of all major quitline stakeholder groups, including 4 quitline funders and administrators, 2 service providers, and 2 researchers or evaluators. The research team met weekly and conversed daily via e-mail, creating draft documents for the work group to review. The research team and the work group met monthly during the first year of the study (2009), providing feedback on instrument design and testing, review of the analysis, and interpretation of results.

Survey Materials

We selected the practices using a 2-step process. First, we conducted a literature review to identify evidence-based or “emerging” (novel, with little documented evidence but potential impact) practices for increasing either the reach or efficacy of quitlines. In addition to the peer-reviewed literature, we evaluated documents from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that specifically referenced quitlines.13,14 As a second step, NAQC staff and the work group identified practices that were considered future strategies—those under consideration or being discussed by quitlines without much (or any) evidence of effectiveness for improving quit rates or reach. These were practices that many quitlines were discussing on the NAQC communitywide Listserv because of the potential for increasing the impact of quitlines by increasing either reach or efficacy.15 Table 1 provides a full list of practices included in the study for year 1.

TABLE 1—

Tobacco Quitline Practices by Evidence Level, Implementation, and Correlation With Treatment Reach and Spending per Smoker: United States and Canada, 2009

| Quitline Practice | Efficacy Evidence Level | Reach Evidence Level | Quitlines Reporting “Full” or “High” Implementation (n = 62), No. | Correlation of Implementation Score With Quitline-Level Treatment Reach, r | Correlation of Implementation Score With Quitline-Level Spending per Smoker, r |

| Provide a multiple-call protocol (≥ 2 calls for the same quit attempt). | B | D | 57 | −0.23 | −0.34** |

| Provide self-help materials for tobacco users regardless of the reason for calling or services selected. | A | D | 53 | 0.02 | −0.05 |

| Provide reactive (inbound) counseling. | B | D | 51 | 0.04 | −0.09 |

| Provide self-help materials to proxy callers (nontobacco users calling on behalf of, or to help, someone else). | B | D | 51 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

| Provide proactive (outbound) telephone counseling. | A | B | 50 | 0.03 | −0.08 |

| Conduct an evaluation of the effectiveness of the quitline. | C | D | 48 | 0.07 | 0.19 |

| Serve callers without insurance coverage. | C | B | 46 | 0.04 | 0.20 |

| Fax-to-quit or fax referral program. | D | B | 46 | −0.20 | −0.16 |

| Provide self-help materials for tobacco users who receive counseling. | A | D | 46 | 0.23 | 0.16 |

| Provide free (or discounted) nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) to callers.a | A | B | 37 | 0.26 | 0.28* |

| Provide counseling immediately to all callers who request it (either through real-time staff capacity or on-call staff capacity). | C | D | 37 | 0.14 | −0.06 |

| Conduct mass media promotions for the mainstream population. | B | B | 35 | 0.41** | 0.30* |

| Train provider groups on the first 2 or 3 A's (Ask whether a patient uses tobacco, Advise them to quit, Assess their interest in quitting) and refer interested patients to quitlines (with or without a fax referral program). | B | B | 32 | 0.16 | 0.09 |

| Integrate telephone counseling with Web-based, Internet-based or e-Health programs through referrals or combinations of phone and those services. | B | D | 30 | −0.05 | −0.15 |

| Conduct mass media promotions for targeted populations. | B | B | 25 | 0.27 | 0.31* |

| Integrate telephone counseling with face-to-face cessation services through referrals or combinations of phone and those services. | D | D | 25 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| Refer callers with insurance to health plans that provide telephone counseling. | C | D | 18 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| Staff the quitline with counselors who meet or exceed masters-level training. | D | D | 14 | −0.20 | −0.13 |

| Recontact relapsed smokers for reenrollment in quitline services. | C | B | 12 | −0.08 | −0.12 |

| Obtain Medicaid or other insurance reimbursement for counseling provided to callers. | B | D | 8 | −0.06 | 0.16 |

| Supplement quitline services with Interactive Voice Response (IVR) services (e.g., automated check-in IVR calls for relapse prevention). | C | D | 4 | 0.03 | 0.19 |

| Use text messaging to provide tailored support with, or instead of, telephone counseling. | B | D | 2 | 0.11 | −0.10 |

Note. A = practices that are effective, as indicated by findings of 1 or more meta-analyses or multiple high-quality single studies; B = practices with only 1 high-quality, or several inferior-quality (smaller sample size, single site, or small effect size), peer-reviewed journal articles and no meta-analyses documenting their effectiveness; C = practices that have been recommended by a reputable organization such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention but have no peer-reviewed journal articles documenting their effectiveness; D = practices that were not supported by any scientific evidence or recommendations from reputable organizations.

The survey included 2 NRT-related practices: provide free (or reduced) NRT to callers without requiring registration for telephone counseling, and provide NRT but require registration for counseling. On the basis of qualitative follow-up with survey respondents, we combined the 2 practices; the highest level of implementation for either NRT practice was recorded as the final response for “provide free (or discounted) NRT to callers.”

*P < .05; **P < .01.

Procedures

Once we selected practices for inclusion, we categorized each by efficacy and reach on the basis of evidence from the tobacco control research literature available as of December 31, 2009. Although the literature base is continually growing, we limited ourselves to evidence available at the time of data collection to most closely match the information that was available to study participants. One consequence is some practices are classified here as having different levels of evidence than they do today. For example, Free et al.16 published data in 2011 demonstrating the effectiveness of text messaging for increasing quit rates. There have also been at least 3 published meta-analyses showing similar results.17–19 Therefore, text messaging would be considered an A-level practice by today’s standards, but only a D-level practice in 2009.

We identified a list of search terms and modified it as needed to locate peer-reviewed publications for each of the 22 practices (Appendix 1, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). We used Google Scholar to conduct the search. In addition, we mined the reference lists for the 2008 Public Health Service Guideline for Treating Tobacco Dependence3 and the 2007 Cochrane Review4 to identify additional citations relevant to the available evidence for each of the 22 practices. The Google Scholar search returned 1220 articles. We used 56 articles to classify practices. In this article, “efficacy” refers to whether a practice increased quit rates at levels that were statistically significant. “Reach” refers to whether a practice led to statistically significant increased use of the quitline service.

We developed a rating scale loosely based on the Public Health Service Guideline strength-of-evidence classification. The Public Health Service provides letter grades based on the quality of evidence. A-level findings are supported by consistent findings from clinical trials, B-level findings are based on less consistent evidence, and C-level findings are defined as “reserved for important clinical situations in which the Panel achieved consensus on the recommendation in the absence of relevant randomized controlled trials.”3(p77) Our system categorized practices relative to whether a practice had the potential to increase efficacy or reach. Practices that were effective, as indicated by consistent findings of 1 or more meta-analyses, were rated A. Practices with consistent findings by multiple observational studies, mixed or weak findings by multiple rigorous or randomized studies or meta-analyses, or findings that were strong for in-person counseling but weaker for quitline counseling, were rated B. Practices recommended by a reputable organization such as the CDC but with no high-quality peer-reviewed journal articles documenting their effectiveness were rated C. Finally, practices that were not supported by any scientific evidence or recommendations from reputable organizations were rated D. We considered A- and B-level practices as “evidence-based” and C- and D-level practices as “emerging” or “future” strategies. There was no evidence that any of the practices included here reduced efficacy or reach (Table 1).

To assess implementation of practices, survey respondents were asked first whether they were aware of each practice. If they endorsed “awareness,” they were asked at what stage of the decision-making process they were in. The response options were “have not yet discussed the practice,” “in discussion,” “decided not to implement the practice,” and “decided to implement the practice.” If participants selected “decided to implement the practice,” they were asked what stage of implementation their organization was in: “no progress,” “low level of implementation (e.g., some discussion, staff informed, someone assigned to lead the process),” “medium level of implementation (e.g., a formal plan for implementation exists, resources have been committed, training has begun),” “high level of implementation (e.g., a pilot project has been implemented or other testing has begun),” or “full implementation (the practice has become part of the quitline’s policy or standard operating procedures for all eligible callers).”All survey respondents were asked to respond for each of the 22 quitline practices listed in Table 1. Survey respondents completed surveys in June and July 2009.

Participants

Each quitline consisted of a partnership between 1 funder–administrator organization and 1 service provider organization. Several service providers contracted with multiple state or provincial funder–administrators; in all, 87 quitline organizations formed partnerships to fund and operate 63 state and provincial quitlines. A detailed description of the network of quitlines and quitline organizations has been previously reported.9 We recruited survey respondents by asking the 87 quitline organizations (both funder–administrator and service provider organizations) to identify all personnel involved with decision-making regarding implementation of quitline practices. Potential respondents included quitline contract managers, directors of state tobacco control programs, communications staff, client managers (for service provider organizations), medical directors, and chief executive officers. For year 1 of this study, we identified 273 potential participants, representing 87 organizations making up 63 quitlines. We sent potential respondents an invitation e-mail explaining the study’s purpose, why and how they had been selected as potential respondents, and the survey process. We followed up nonresponders by e-mail and phone. Of the 273 potential participants, 176 (64.5%) completed the implementation section of the survey. Respondents represented 62 of 63 (98.4%) of the full population of quitlines. Nonresponders, who tended to be executive leadership less closely connected to daily quitline operations, were not identified as key responders for their organization.

Preliminary Analysis

Preliminary results showed that for cases in which a single quitline had several respondents who completed the survey, there were many instances in which respondents gave widely divergent responses for a single practice (e.g., for a given practice, 1 respondent reported “full implementation” while another reported “decided not to implement”). On the basis of qualitative follow-up with study respondents, it became apparent that typically a single person for each funder and service provider partner organization was most knowledgeable about, and thus best positioned to report on, the implementation status of the practices for that quitline. As a result, we identified a single “key” respondent for the implementation section of the survey for each of the 83 responding quitline organizations, either by matching respondents with organizational “key responders” in years 2 and 3 of the survey or by confirming their status by contacting each organization by e-mail.

Once a single respondent was identified for each quitline organization, we combined responses to each practice to form a single implementation score for each quitline. In some cases, there were discrepant implementation scores for a given practice reported by quitline partner organizations. For example, a funder might report awareness of a practice whereas the service provider indicated full implementation. Through consultation with NAQC staff and the advisory work group, we determined that certain practices were typically within the operational sphere of the funder–administrator organization and others were typically within the operational sphere of the service provider organization. As a case in point, media campaigns and promotional efforts were generally carried out by quitline funder organizations, whereas practices more closely related to the counseling interaction itself, such as staffing the quitline with masters-level counselors, were generally under the purview of the service provider organization. In cases in which there were discrepant responses from the funder and service provider organization for a given practice in the “funder sphere,” the funder response served as the final response for the quitline for that practice. For practices known to be in the “service provider sphere,” the service provider response served as the final response for the quitline.

RESULTS

We analyzed 3 questions in this study of types of practice in US and Canadian quitlines.

Question 1

Question 1 was, “To what extent were different types of practices implemented within and across quitlines?

Analysis.

We calculated the frequency of quitlines reporting “high” or “full” implementation of the 22 practices. Quitlines reporting high implementation were grouped with (added to) quitlines reporting full implementation to create the group of “full or high” implementers for each practice. The numbers of quitlines implementing each practice at a full or high level are reported in Table 1.

Results.

Implementation rates ranged from 3% (n = 2; text messaging) to 92% (n = 57; providing a multiple-call protocol). More than half of the quitlines implemented 13 practices, covering areas of quitline services (providing proactive counseling, providing reactive counseling, providing a multiple-call protocol, providing nicotine replacement therapy [NRT]), quitline policies (providing counseling immediately to all callers requesting it, serving callers without insurance coverage), quitline materials (providing self-help materials to proxy callers, to those who receive counseling, and to all callers), quitline promotions and outreach (conducting mass media promotions for the mainstream population, providing a fax referral program, and training providers on referral to quitlines), and conducting an evaluation of the effectiveness of the quitline. Five practices were implemented by fewer than one quarter of quitlines: staffing the quitline with counselors having at least a masters degree, recontacting relapsed smokers for reenrollment in the quitline, obtaining Medicaid reimbursement for counseling, using Interactive Voice Response technology to supplement quitline services, and using text messaging to provide cessation support (Table 1).

Question 2

Question 2 was, “What are the patterns of implementation of practices grouped by research evidence level?”

Analysis.

We determined the mean proportion of quitlines implementing practices in each evidence level for both reach and efficacy by calculating the proportion of quitlines reporting full or high implementation for each practice, and taking the mean of the proportions for all practices in each evidence grouping (Table 2). For example, if there were 3 practices in the A-level grouping for reach evidence, and the proportion of quitlines implementing each practice at either a full or high level was 0.75, 0.70, and 0.60, the mean proportion of quitlines implementing A-level reach practices would be the average of 0.75, 0.70, and 0.60, or 0.68. We then compared the mean proportions for each significance grouping for significance. We determined significance using a dependent samples t-test of proportions.

TABLE 2—

Implementation of Tobacco Quitline Practices, by Evidence Level: United States and Canada, 2009

| Evidence Group | Quitlines Implementing Each Type of Practice, Mean % |

| A level for efficacy | 73.8 |

| B level for efficacy | 51.3 |

| A or B level for efficacy | 58.3 |

| C level for efficacy | 43.7 |

| D level for efficacy | 44.9 |

| C or D level for efficacy | 44.1 |

| B level for reach | 56.2 |

| D level for reach | 50.3 |

Note. A = practices that are effective, as indicated by findings of 1 or more meta-analyses or multiple high-quality single studies; B = practices with only 1 high-quality, or several inferior-quality (smaller sample size, single site, or small effect size), peer-reviewed journal articles and no meta-analyses documenting their effectiveness; C = practices that have been recommended by a reputable organization such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention but have no peer-reviewed journal articles documenting their effectiveness; D = practices that were not supported by any scientific evidence or recommendations from reputable organizations.

Results.

Although there was no statistically significant difference between the mean proportion of quitlines implementing A-level and B-level practices for efficacy (P = .109), a higher proportion of quitlines implemented A-level practices than C-level practices for efficacy (P = .026), and a higher proportion of quitlines implemented A-level practices than D-level practices for efficacy (P = .033). There was no statistically significant difference between the mean proportion of quitlines implementing higher (B-level) practices for reach and lower (D-level) practices for reach (P = .651).

Question 3

Question 3 was, “Was there any relationship between implementation of practices (individually or grouped by research evidence level) and either spending levels for quitlines or actual treatment reach outcomes?”

Analysis.

We calculated a mean implementation score for each quitline for each evidence group of practices. Each quitline reported a level of implementation for each practice (ranging from 0 to 6). For each evidence level grouping, we calculated the mean implementation score for each quitline. For example, if there were 3 A-level reach practices and a quitline reported implementation levels of 1, 5, and 6, its mean implementation score for A-level reach practices would be (1+5+6)/3, or 4.0. For each practice grouping, we estimated correlations between mean implementation score and reach and spending. We obtained reach and spending data from the 2009 NAQC Annual Survey of Quitlines.20 We calculated treatment reach by dividing the number of tobacco users receiving counseling or medications from the quitline by the number of adult smokers in the state or province as estimated by the 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System or Canadian Tobacco Use Measurement Survey. We calculated spending by taking the total budget for quitline counseling services and medications and dividing it by the number of adult smokers in the state or province, thus correcting for differences in the size of the target population for each quitline. Table 3 provides the distribution of mean implementation scores, spending per smoker, and treatment reach.

TABLE 3—

Mean Implementation Scores, Spending per Smoker, and Treatment Reach Distributions for Tobacco Quitlines: United States and Canada, 2009

| Variable | Mean | Median | Minimum | Maximum | SD |

| Mean implementation score for A-level efficacy practices | 3.65 | 4.0 | 0 | 6 | 1.35 |

| Mean implementation score for B-level efficacy practices | 4.28 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 6 | 0.88 |

| Mean implementation score for C-level efficacy practices | 3.37 | 3.36 | 1.0 | 6 | 0.94 |

| Mean implementation score for D-level efficacy practices | 3.77 | 3.83 | 1.33 | 6 | 1.35 |

| Mean implementation score for B-level reach practices | 3.74 | 3.81 | 1.38 | 5.75 | 0.99 |

| Mean implementation score for D-level reach practices | 3.77 | 3.87 | 1.13 | 5.53 | 0.78 |

| Spending per smoker on counseling and medications, $ | 3.11 | 1.63 | 0 | 19.89 | 4.09 |

| Treatment reach, % | 1.55 | 0.60 | 0.05 | 7.21 | 1.83 |

Note. A = practices that are effective, as indicated by findings of 1 or more meta-analyses or multiple high-quality single studies; B = practices with only 1 high-quality, or several inferior-quality (smaller sample size, single site, or small effect size), peer-reviewed journal articles and no meta-analyses documenting their effectiveness; C = practices that have been recommended by a reputable organization such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention but have no peer-reviewed journal articles documenting their effectiveness; D = practices that were not supported by any scientific evidence or recommendations from reputable organizations. Each quitline reported a level of implementation for each practice (ranging from 0 to 6). For each evidence level grouping, we calculated the mean implementation score for each quitline. We obtained reach and spending data from the 2009 North American Quitline Consortium Annual Survey of Quitlines.20 We calculated treatment reach by dividing the number of tobacco users receiving counseling or medications from the quitline by the number of adult smokers in the state or province as estimated by the 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System or Canadian Tobacco Use Measurement Survey. We calculated spending by taking the total budget for quitline counseling services and medications and dividing it by the number of adult smokers in the state or province.

In addition to correlations between implementation of practices grouped by treatment level and treatment reach and spending levels, we also estimated correlations between (1) implementation of each individual practice and treatment reach and (2) implementation of each individual practice and spending levels for quitlines. Each quitline reported a level of implementation for each practice (ranging from 0 to 6). For each practice, we ran correlations between implementation level and treatment reach and between implementation level and quitline spending level for counseling and medications (Table 1).

Results.

Implementation of practices showing higher levels of evidence (B level) for increasing reach showed a moderate, but significant, positive correlation with both treatment reach (r = 0.39; P = .007) and spending per smoker (r = 0.36; P = .006). Implementation of practices with higher levels of evidence (A or B level) for increasing efficacy showed a moderate, but significant, positive correlation with treatment reach (r = 0.36; P = .01). Implementation of A-level efficacy practices showed a moderate, but significant, positive correlation with spending per smoker (r = 0.30; P = .02).

When examined individually, implementation of only a few practices was correlated with quitline-level treatment reach or spending per smoker. Only 1 practice, conducting mass media promotions for the mainstream population, was moderately but significantly positively correlated with treatment reach (r = 0.41; P = .004). Several practices were correlated with spending per smoker. Providing a multiple-call protocol was moderately and negatively correlated with spending per smoker (r = −0.34; P = .009). In addition, providing NRT, conducting mass media promotions for the mainstream population, and conducting mass media promotions for a targeted audience were all moderately and positively correlated with spending per smoker (NRT: r = 0.28; P = .05; media mainstream: r = 0.30; P = .05; media targeted: r = 0.31; P = .05; Table 1).

The strongest correlation found was between treatment reach and spending per smoker (r = 0.80; P < .01; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Scatterplot of tobacco quitline treatment reach (proportion of tobacco users served by quitlines) by spending per smoker (quitline spending on counseling and medications): United States and Canada, 2009.

DISCUSSION

Although there were several practices that were significantly positively correlated with spending per smoker, and 1 practice significantly positively correlated with treatment reach, all correlations between practices and either spending or reach were moderate. The strongest relationship found was between spending per smoker and treatment reach (r = 0.80; P < .001) (Figure 1). This stands to reason, because treatment reach is a measure of how many tobacco users received services (counseling or medications) from quitlines, and spending per smoker is a measure of how much was spent on those services (counseling and medications). Contractual information is proprietary and not available for most quitlines. However, assuming that most quitline contracts operate on a per-unit cost basis, an increase in the number of people served results in a corresponding increase in the amount spent on those services. The implication of this is intuitive but critically important: if quitlines are to support the vision of the CDC and others and serve 6% of tobacco users with counseling and medications, they must be funded at an appropriate level.

Beyond funding, the positive correlation between reach and conducting mass media promotions for the mainstream population merits further investigation; specifically, the fact that it was the only practice to be correlated with treatment reach. Other studies have shown increased demand for services (call volume) following implementation of the offer of free NRT through a quitline,21–24 but providing NRT itself was not correlated with increased reach. It may be that mass media promotions for the mainstream population have a stronger relationship with reach than does providing NRT, since potential quitline users may find out about the offer of free NRT only through mass media promotions. It will be important to investigate the relationship between the specific content of media promotions and their impact on reach, to capitalize on this relationship, and to determine the role of messages related to NRT.

Fourteen quitlines reported not implementing mass media campaigns. Among these quitlines, only 1 practice, providing NRT without requiring counseling, was significantly correlated with treatment reach. It is not clear why providing NRT and requiring counseling, or the combined NRT measure, were not significantly correlated with increased treatment reach, although the small number of cases underpowers any such calculations and should be interpreted with caution.

Several quitline practices were correlated with spending per smoker (services and medications). Providing NRT was positively and moderately correlated with spending. Given that spending per smoker includes spending on smokers’ medications, this finding confirms what we would expect to see. In addition, conducting mass media campaigns for both mainstream and targeted populations was correlated with spending per smoker. Given the correlation between mass media promotions and reach, conducting mass media campaigns may increase the number of tobacco users calling, and being served by, quitlines, which would increase the amount being spent on services. Therefore, although media campaigns are not captured by the spending per smoker calculation, the findings from this study make sense.

Providing a multiple-call protocol was moderately and negatively correlated with spending per smoker. In other words, quitlines offering a multiple-call protocol (more than 1 counseling call per quit attempt) tend to spend less on quitline services and medications per adult smoker in the state or province. It may be that the contract mechanisms for offering a multiple-call protocol are more cost-effective than other types of counseling protocols (e.g., single call) since the time spent collecting intake data only has to be done once, whereas a single-call protocol must include the collection of intake data for every call. It may also be that quitlines offering a multiple-call protocol tend to include those that do not provide free medications to tobacco users, which could lower their costs. According to our findings, however, spending per smoker is most strongly correlated with treatment reach, or the proportion of tobacco users served in the state or province. Providing a multiple-call protocol may be a mediating factor in overall costs, but it may have little predictive value in determining spending levels for quitlines. To understand what impact a multiple-call protocol might have on spending amounts, we may need to look more closely at metrics such as spending per user rather than spending per smoker, or consider the average number of calls completed per tobacco user.

Limitations

Most of the limitations of this study are related to the data collection methodology we used, which was driven by the absence of objective, secondary data on all 22 quitline practices included in this study. Despite the limitations of the data we were able to collect, we did collect data from nearly every quitline, and thus we believe that our findings are especially helpful in providing an in-depth overview and understanding of the full range and evidence base of quitline practices throughout the United States and Canada.

Because a few service provider organizations are linked to multiple quitlines, lack of participation from any of those organizations would result in missing data for multiple quitlines. However, we collected data from both service provider and funder organization respondents, so where responses were missing from 1 type of organization, we typically received it from the other. There were only 5 organizations that did not provide any information on implementation of practices, resulting in only 1 quitline with no implementation data provided by either funder or service provider.

One factor that may be influential for achieving a higher quitline reach or quit rate is the cost-effectiveness of quitline practices. A- and B-level evidence practices for both efficacy and reach were moderately, but significantly, positively correlated with spending per smoker. Although cost-effectiveness has been examined for quitlines overall25–27 and for provision of NRT,23,28,29 there was not sufficient evidence on cost-effectiveness for all the practices included in this study to allow us to include it in a meaningful way. The influence of cost-effectiveness evidence should be included in any qualitative research on implementation of quitline practices, as it could be a critical factor in quitline decision-making on implementation.

The primary analysis methodology used for this report was identifying correlations between quitline practices, reach, and spending levels. Correlations, although useful tools and appropriate for the associative nature of our research questions, do not provide information on the directionality of causation. In addition, they do not allow for close examination of outliers. Findings from this study show that mass media promotions are related to reach, as are spending levels on services and medications. However, it does not identify whether there are quitlines spending less on promotions or services that still achieve higher reach levels. Qualitative case studies of such quitlines would add enormous value to the field.

Conclusions

To our knowledge this is the first comprehensive attempt to describe the state of quitlines regarding practices with varying levels of evidence for improving efficacy or reach. Given the prominence of quitlines in the public health strategies of both the US and Canadian federal governments, and the potential of quitlines to help large numbers of tobacco users quit, this information is critical for better understanding how quitlines operate, what services and practices they employ, and what kinds of studies are needed to help improve quitline practice in the future.

The clear relationship between quitline spending and reach reinforces the need to continue funding for quitlines, and to increase funding to levels commensurate with national cessation goals. The finding that mass media promotion of quitlines is related to reach is neither surprising nor novel, but the lack of a relationship between provision of NRT and reach was conspicuous by its absence. Further research into the specific content of existing promotional efforts, and how content influences demand for quitline services, will be a useful addition to the field. Finally, there is a need for an assessment of the level of awareness of quitline decision-makers regarding existing evidence for various practices. It may be that providing a mechanism for quitline decision-makers to access up-to-date information about the state of the science for quitline practices will improve the rates of implementation of evidence-based practices.

One important conclusion of our study is based on the significant relationship between implementation of quitline practices and higher levels of evidence for those practices. This seems to indicate that quitlines are sufficiently informed about practices that will improve efficacy and reach. The NAQC’s recent issue paper on Quitline Service Models is a good example of work in this area.30 The relationship between implementation and evidence does not, however, provide any better understanding of what specific factors influence quitline decision-makers about implementing new practices. To improve our ability to increase implementation of evidence-based quitline practices, we need additional qualitative research. What role does level of evidence play for quitline decision-makers? How do cost concerns factor in? It may be that recommendations by the CDC or other parties are sufficient to spur implementation, or that the knowledge translation efforts of the NAQC and other organizations help to spread awareness of potential practices and aid in implementation efforts. The recent report by Terpstra et al. on implementation of the quitline evaluation practice is a good start in this direction.31

The 2 practices with the lowest number of quitlines reporting high or full implementation rely on newly emergent technology. There is little evidence of the effectiveness of these practices to increase the reach or efficacy of quitlines, in part because of the relative youth of the practices themselves. It will be important to observe any changes in the levels of implementation of these practices over time.

Given the high degree of homogeneity with respect to implementation of practices across North American quitlines, future studies will need to identify other emerging practices over time. In addition, decreases in tobacco control and quitline budgets may lead to greater variability of practices. To improve our understanding, researchers must identify changing trends in quitline practices over time and potential correlations to environmental or other factors.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (#R01CA128638). This article is dedicated to the memory of our coauthor, Keith Provan, who passed away on February 16, 2014.

We thank each of the quitline funders and vendors for participating in this project, and in particular we are grateful to our quitline work group for providing guidance to us to make the study most useful to the quitline treatment community. In addition, we acknowledge Linda Bailey, president and CEO of the North American Quitline Consortium, for her review of several versions of this manuscript, and RaeAnne Davis for additional analysis and research assisting with the response to reviewers.

Human Participant Protection

The University of Arizona institutional review board and the Mayo Clinic institutional review board both provided human participant approval for this study.

References

- 1.Lichtenstein E, Zhu SH, Tedeschi GJ. Smoking cessation quitlines: an underrecognized intervention success story. Am Psychol. 2010;65(4):252–261. doi: 10.1037/a0018598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Results From the 2011 NAQC Annual Survey of Quitlines. Phoenix, AZ: North American Quitline Consortium; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiore M, Jaén C, Baker T . Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stead LF, Perera R, Lancaster T. A systematic review of interventions for smokers who contact quitlines. Tob Control. 2007;16(suppl 1):i3–i8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stead LF, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD002850. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002850.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lichtenstein E, Glasgow RE, Lando HA, Ossip-Klein DJ, Boles SM. Telephone counseling for smoking cessation: rationales and meta-analytic review of evidence. Health Educ Res. 1996;11(2):243–257. doi: 10.1093/her/11.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan W. Proactive telephone counseling as an adjunct to minimal intervention for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(3):416–427. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stead LF, Lancaster T, Perera R. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1):CD002850. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leischow SJ, Provan K, Beagles J et al. Mapping tobacco quitlines in North America: signaling pathways to improve treatment. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(11):2123–2128. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonito JA, Ruppel EK, Saul JE, Leischow SJ. Assessing the preconditions for communication influence on decision making: The North American Quitline Consortium. Health Commun. 2013;28(3):248–259. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.673245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Provan K, Beagles J, Mercken L, Leischow S. Awareness of evidence-based practices by organizations in a smoking cessation network. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2012 doi: 10.1093/jopart/mus011. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummins SE, Bailey L, Campbell S, Koon-Kirby C, Zhu SH. Tobacco cessation quitlines in North America: a descriptive study. Tob Control. 2007;16(suppl 1):i9–i15. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Telephone Quitlines: A Resource for Development, Implementation and Evaluation. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrams DB, Orleans CT, Niaura RS, Goldstein MG, Prochaska JO, Velicer W. Integrating individual and public health perspectives for treatment of tobacco dependence under managed health care: a combined stepped-care and matching model. Ann Behav Med. 1996;18(4):290–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02895291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Free C, Knight R, Robertson S et al. Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): a single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9785):49–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60701-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Civljak M, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, Sheikh A, Car J. Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD007078. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007078.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Borland R, Rodgers A, Gu Y. Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD006611. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006611.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YF, Madan J, Welton N et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of computer and other electronic aids for smoking cessation: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(38):1–205. doi: 10.3310/hta16380. iii–v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.FY2009 NAQC Annual Survey of Quitlines. Phoenix, AZ: North American Quitline Consortium; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.An LC, Schillo BA, Kavanaugh AM et al. Increased reach and effectiveness of a statewide tobacco quitline after the addition of access to free nicotine replacement therapy. Tob Control. 2006;15(4):286–293. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tinkelman D, Wilson SM, Willett J, Sweeney CT. Offering free NRT through a tobacco quitline: impact on utilisation and quit rates. Tob Control. 2007;16(suppl 1):i42–i46. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.019919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fellows JL, Bush T, McAfee T, Dickerson J. Cost effectiveness of the Oregon quitline “free patch initiative.”. Tob Control. 2007;16(suppl 1):i47–i52. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.019943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheffer MA, Redmond LA, Kobinsky KH, Keller PA, McAfee T, Fiore MC. Creating a perfect storm to increase consumer demand for Wisconsin’s Tobacco Quitline. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(3 suppl):S343–S346. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lal A, Mihalopoulos C, Wallace A, Vos T. The cost-effectiveness of call-back counselling for smoking cessation. Tob Control. 201;Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Rasmussen SR. The cost effectiveness of telephone counselling to aid smoking cessation in Denmark: a modelling study. Scand J Public Health. 2013;41(1):4–10. doi: 10.1177/1403494812465675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomson T, Helgason AR, Gilljam H. Quitline in smoking cessation: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(4):469–474. doi: 10.1017/s0266462304001370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cummings KM, Hyland A, Carlin-Menter S, Mahoney MC, Willett J, Juster HR. Costs of giving out free nicotine patches through a telephone quit line. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2011;17(3):E16–E23. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182113871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollis JF, McAfee TA, Fellows JL, Zbikowski SM, Stark M, Riedlinger K. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of telephone counselling and the nicotine patch in a state tobacco quitline. Tob Control. 2007;16(suppl 1):i53–i59. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schillo B. North American Quitline Consortium. Quitline Service Offering Models: A Review of the Evidence and Recommendations for Practice in Times of Limited Resources. Phoenix, AZ: North American Quitline Consortium; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terpstra J, Saul J, Best A, Leischow S. The complexity of institutionalizing evaluation as a best practice in North American quitlines. Am J Eval. 2013;34(3):356–371. [Google Scholar]