Abstract

The cultural divide between US military and civilian institutions amplifies the consequences of military discharge status on public health and criminal justice systems in a manner that is invisible to a larger society. Prompt removal of problematic wounded warriors through retributive justice is more expedient than lengthy mental health treatment.

Administrative and punitive discharges usually preclude Department of Veterans Affairs eligibility, posing a heavy public health burden. Moving upstream—through military rehabilitative justice addressing military offenders’ mental health needs before discharge—will reduce the downstream consequences of civilian maladjustment and intergenerational transmission of mental illness.

The public health community can play an illuminating role by gathering data about community effect and by advocating for policy change at Department of Veterans Affairs and community levels.

Although there has been much attention since the attacks of September 11, 2001, regarding the effect of combat on service members and some attention to the effect on military families, there has been scant consideration to the structural components within the military and Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) systems that bar some veterans from VA services because of their discharge status. These components can and should be modified to prevent a public health crisis of great magnitude that will only grow over time. The cultural divide between military and civilian institutions in the United States 1 amplifies the consequences of discharges on the American public health system in a manner that is invisible to a larger civilian society. When a returning service member has posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anger problems, and misconduct, it is easier for the military to criminalize the behavior and to discharge the service member other than honorably than it is to treat the disorder. Military commanders do not want to be burdened by wounded warriors who are problematic. As such, retributive discharge proceedings offer an expedient option to lengthy treatment of the ongoing issue of an unfit service member. Ultimately, many of these service members are left without VA eligibility to address the mental health trauma caused by their service. The effect of the commander’s desire for prompt removal of wounded warriors from the military heavily burdens the community’s public health systems. Accordingly, we suggest that moving upstream—that is, through military rehabilitative justice focusing on the mental health needs of military offenders before discharge—will reduce the downstream consequences of civilian maladjustment and intergenerational transmission of mental illness. Moreover, we argue that the military justice system has the obligation to address the issues before they translate into risk and danger in the community.

We provide a brief overview of postdeployment health problems, combat and criminal behavior, and effect of military justice on postmilitary treatment access on family and occupational functioning; outline the rationale for the rehabilitative military justice as an alternative to punitive systems to reduce the negative social and consequent public health outcomes for combat-traumatized service members; and encourage review and adoption of policy options and public health advocacy.

HEALTH ISSUES AMONG RETURNING VETERANS

More than 2.5 million service members have deployed in the Global War on Terrorism, including Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation Enduring Freedom, and Operation New Dawn.2 Conservatively, one third have been estimated to have war-zone-based stress injuries.3 The magnitude of the connection, or nexus, between war-zone injuries, misconduct, and criminal behavior (both before and after military service) during the Global War on Terrorism and exclusion from VA benefits and treatment after discharge is not known. From the military side, between 2001 and 2011, misconduct separations increasingly accounted for the US Army’s 179 012 administrative (i.e., nonjudicial) separations, reflecting many returning service members who, as veterans, will have no access to VA services.4 On the community side, the US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, estimated in 2007 that 703 000 veterans were under correctional supervision (in custody or under parole or probation) and that veterans were 9.6% of the 12 million Americans arrested.5,6 Furthermore, earlier Bureau of Justice Statistics jail and prison surveys published in 2000 and 2007 documented high levels of emotional and mental health problems, reported that approximately 20% of veterans in custody lack the character of military discharge (i.e., honorably discharged) to access appropriate VA treatment on release from custody, and found that veterans not honorably discharged had more serious criminal and substance abuse histories than did those honorably discharged.5,7 Although these data are not inclusive of the universe of those at risk in the nexus of concern here, they indicate that, conservatively, tens of thousands of these returning service members have already surfaced in the nonmilitary justice system.

Both large-scale civilian3 and military8 reports have documented what Rand Corp3 has termed the “invisible wounds of war” among returning US service members, the most notable of which are PTSD, depression, and traumatic brain injury. Underlining the unprecedented nature and effect of warfare during the Global War on Terrorism, the military’s Joint Mental Health Advisory Team VII8 report found a decline in individual morale, higher stress rates, high exposure to concussive events, more time in a combat zone, and increased deployments. The experience of America’s Vietnam War veterans is painfully instructive on the persistence of such problems and the postdischarge justice involvement of service members: 10-year follow-up of veterans after the Vietnam War found that approximately 960 000 male and more than 1900 female veterans still had full-blown chronic PTSD and that almost half of all male veterans had a history of arrest or incarceration after discharge, although the correlation to military discharge status was not specified.9 A more recent study of military PTSD found that 38% of the veterans experienced delayed onset of symptoms even 40 to 50 years after initial trauma exposure.10 Such numbers provide a historical benchmark for how many veterans with combat exposure experience long-term mental health and behavioral issues.

COMBAT AND POSTDEPLOYMENT CRIMINAL BEHAVIOR

A recent study of violent offending by British veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars found that both combat exposure and increasing levels of war trauma predicted postdeployment violent offending and strong associations between mental health problems and violent offending.11 The added significance of depression is its association with suicide, an issue of self- and, not infrequently, other-directed violent behavior.12,13

Bureau of Justice Statistics data prior to Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom indicated that 57% of veterans in state prisons in 2004 were incarcerated for violent offenses and that victims of veteran violence were more frequently intimate partners, friends, or acquaintances than were victims of nonveterans (25% vs 11%).7 War-zone exposure has been linked as a risk factor for postdeployment violence aggravated by alcoholism and financial strain, factors that are likely to be augmented for combat veterans with blemished military records.9,14 A large-scale study of predictors of misconduct among 20 746 Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom Marines found that those with postcombat psychiatric disorders were nine times as likely to be separated from the service for behavioral reasons.15

MILITARY JUSTICE AND ITS EFFECT

The Uniform Code of Military Justice was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Harry Truman in 1950.16 Notwithstanding recent significant changes to military law for charges involving sexual assault, the Uniform Code of Military Justice embodies two important principles: (1) individualized sentencing; and (2) the military commander’s control over the legal process, including both administrative separations and courts-martial. Taken together, these principles provide commanders with considerable control and flexibility.

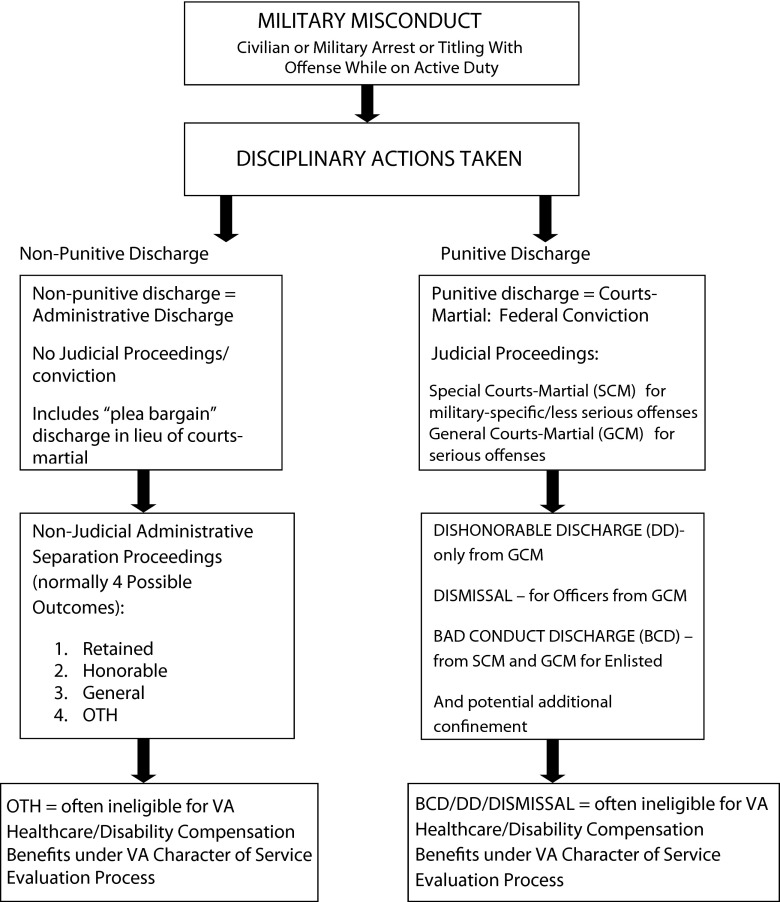

Minor infractions, such as reporting late for duty, can be handled by sanctions (e.g., extra duty, rank reduction).17–19 More serious misconduct can lead to two types of involuntary separations from the service: (1) courts-martial that lead to a conviction and a punitive discharge (bad-conduct discharge, dishonorable discharge, or officer dismissal), or (2) administrative discharges (e.g., other-than-honorable discharge), in which there is no conviction but a blemish in the character of service. The military does not differentiate between felonies and misdemeanors like civilian courts do and, instead, features different types of courts-martial that are statutorily limited in the extent of punishment that can be imposed (e.g., special court-martial vs more severe general court-martial).20 Figure 1 summarizes the disciplinary pathways that can result in being discharged other-than-honorably.

FIGURE 1—

Military misconduct: pathways to discharges that bar Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) benefits.

Note. OTH = other than honorable.

By statute, a dishonorable discharge or an officer dismissal normally precludes all meaningful VA benefits. However, those with a bad-conduct discharge from a special court-martial and those with an administrative other-than-honorable discharge still may be entitled to benefits based on the VA’s evaluation process.17,21 Character of service, whether bad-conduct discharge or other-than-honorable discharge, is a major determinant of future eligibility for VA health care, which normally requires a fully honorable discharge or a general under-honorable-conditions discharge. Both types of disciplinary actions frequently result in loss of VA benefits, often without meaningful distinction in the forum where it is adjudicated.

Commanders want troops who are able to manage their problems despite adverse effects of combat duty. Table 1 summarizes the number of punitive discharges during the Vietnam era and the first decade of the Global War on Terrorism. These statistics demonstrate that the current Global War on Terrorism Era, which did not involve a Draft and did not include as many actively serving personnel, has still resulted in comparable levels of punitive discharges, most evident in far greater numbers of dishonorable discharges, which are traditionally reserved for the most severe military offenders and offenses. In difficult economic times, there will always be an ample supply of recruits, giving commanders more incentive to opt for harsh punishment and less incentive to consider the health and cost burden on society of their decisions.24,25 Moreover, the status of pending disciplinary action places offenders at a substantial disadvantage for obtaining effective mental health treatment by virtue of ineligibility to enter Wounded Warrior programs, practical burdens of pretrial confinement pending court-martial, or the pervasive attitude within a unit’s leadership that treatment following arrest is likely a ploy to evade criminal responsibility.24,25 Instead of promoting service member resilience—the ability to bounce back from adversity, stress, and trauma—the effect of punishment from military justice is only resilience-busting. Service members now have dual problems: those from the war, and those from military justice, setting the stage for revolving door social problems: criminality, mental illness, and drug abuse.24,26 Yet another consequence of a criminal military record is a bar to future employment in occupations service members are uniquely trained to perform (e.g., law enforcement), which has economic consequences not only for the veteran but also for the family.

TABLE 1—

Numbers of Courts-Martial, Bad-Conduct Discharges, and Dishonorable Discharges for Vietnam War and Global War on Terrorism Eras

| Courts-Martial Charges/Case Tried |

Bad-Conduct Discharges |

Dishonorable Discharges |

|

| Period of Active Service | No. | No. | No. |

| Vietnam War Era (July 1, 1964–June 30, 1974) | 164 000 | 31 800 | 2200 |

| Global War on Terrorism Era (October 2001–September 30, 2011) | 41 715 | 23 315 | 3200 |

The expedience of a retributive separation is on the side of the military, and the consequences fall to public health. Community, state, and county health service systems incur the cost of addressing the military’s unfinished business of the mental health trauma caused by military service.26–28 Finally, Schaller29 adds yet another cost to the military’s justice process in the form of heavy financial burdens on state and local criminal justice systems.

MILITARY DISCIPLINARY EFFECT ON FAMILY

Demoralization of the service member within the military justice framework only compounds combat-based psychological problems, and such distress can experientially be borne by family members. Service members’ medical and psychiatric, legal, and related employment problems can and do strain and overwhelm the strongest of spouses or partners. Marital stress often influences the spouse’s work performance and leads to domestic violence, separation and divorce, child custody and support conflicts, parenting problems, and poverty.30 As a testament to these effects, the army reported dramatic increases between fiscal years 2008 and 2011 in domestic violence (50%: from 4827 to 7228) and child abuse (62%: from 3172 to 5149) referrals.4

Vicarious or secondary traumatic stress describes the transmission of a spouse’s or parent’s mental health condition to his or her family members. It is the “signature injury” experienced by military families when the service member spouse or parent has a combat-related mental health condition.31,32 Military children have been found to be more anxious and to have more difficulties in family functioning compared with children of civilians.32–35 Secondary traumatic stress helps explain why children of service members are 2.5 times as likely to develop psychological problems as are American children in general and why children of deployed parents experienced loss and stress beyond normal levels.32,36 Although the full extent of intergenerational trauma transmission remains unknown,36 the inability to obtain needed VA treatment because of one’s discharge status undoubtedly worsens the effect of secondary traumatic stress.

REHABILITATIVE MILITARY JUSTICE

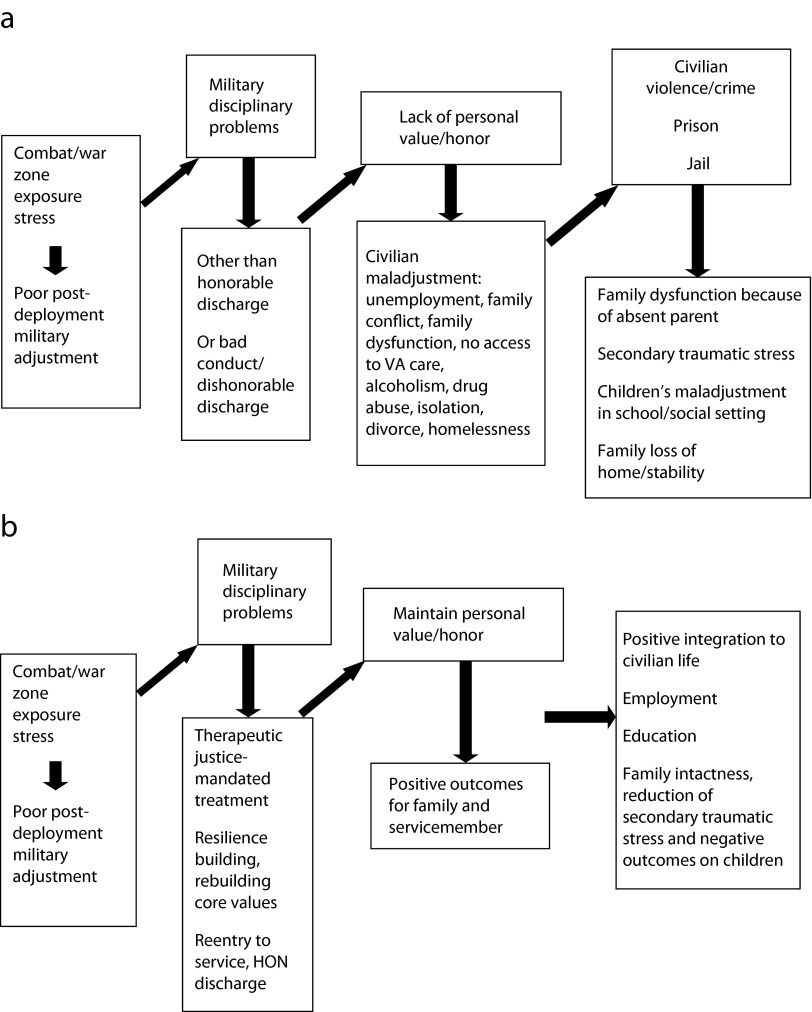

An alternative model to a resilience-busting retributive system is resilience-building rehabilitative justice with a therapeutic purpose.37–39 The cascading negative effect of the untreated and punished service member on public health serves as a contrast to the positive benefits that could be obtained through rehabilitative justice (Figure 2). This concept is not foreign to the military, which has a long but obscured history of rehabilitative justice that has used a problem-solving approach resembling contemporary treatment courts. Examples include the disciplinary companies at the US Disciplinary Barracks of World War I, Service Command Rehabilitation Centers of World War II, and US Army and Air Force discharge remission programs during the Vietnam War through the early 1990s.24

FIGURE 2—

Outcomes of (a) retributive military justice (courts-martial or administrative discharges) and (b) rehabilitative military justice.

Note. HON = honorable; VA = Department of Veterans Affairs.

Rehabilitative justice requires a paradigm shift away from retributive justice and its formulaic application of punishment. Mitigating factors considered on a case-by-case basis with weight given to a service member’s conduct problems that originated from war-zone-related stress would form the process. Civilian Veterans Treatment Courts offer a template for military application for veterans who come into conflict with the law after military discharge.40 Veterans Treatment Courts are courts or court dockets that use a collaborative justice model, consisting solely of veterans; resemble mental health or drug treatment courts; and accept veterans either pre-plea or post-plea typically with misdemeanors or low-level felony offenses. Veterans Treatment Courts employ judges and court staff trained in veteran and military culture, have VA clinicians present at court hearings to facilitate VA enrollment and service access, and almost always have a veteran peer or mentor program that provides instrumental support and supports the adaptive recovery of the veteran during adjudication, treatment, and monitoring.41,42 Veterans Treatment Courts represent a successful rehabilitative paradigm for Iraq and Afghanistan veterans: 7724 veterans had been admitted to 168 veteran-focused courts through 2012; slightly more than two thirds (69%) of the veterans admitted had successfully completed the program.43 Veterans Treatment Courts target regaining military core values (e.g., integrity, honor, respect) and promote mental health to reduce criminal recidivism, concepts that are readily transferable to military court.40,43,44

Parameters for the application of rehabilitative military justice could include use for specific crimes linked to combat stress (e.g., desertion, failure to obey orders, driving offenses, use of drugs or alcohol, lesser violent offenses), result in suspended sentences of less-than-honorable discharges or confinement, and span a specified period (e.g., 18 months).24 When arranged through pretrial agreements in courts-martial, the appropriate commander would have authority to suspend discharges for combat-traumatized offenders and institute treatment-based mandates. The suspended sentence would be remitted on the service member’s treatment participation for combat stress or drug abuse and on other specified conditions. Treatment could be conducted at the VA, under command supervision, or through transfer to the Veterans Treatment Courts authority in the state where the service member will reside. Other collaborations are possible, such as the Warrior Transition Unit or existing Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness postdeployment resilience modules.

CONCLUSIONS

Many combat-traumatized service members under current military discipline incur dual problems: untreated wounds of war and a blemished military record that precludes access to VA health and other benefits. Adversarial military justice has negative consequences for family members of service members: even when the family is not directly harmed by physical abuse or child neglect,24,33 all family members, especially children, face a substantial risk of acquiring secondary traumatic stress by virtue of the veteran’s inability to receive comprehensive mental health care and disability compensation—posing a clear public health concern.25 Marital conflict may escalate to physical violence with lack of treatment.

The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development articulated Principle 15.45 This precautionary principle, recognized in modern disaster and terrorism mitigation efforts,46 mandates that governments mitigate a potential public threat, even if that threat is unpredictable or appears remote, so long as the threat could cause significant danger when it does occur. To avoid creating a class of veterans who are unable to receive treatment of the conditions that are frequently implicated in offending, the military must recognize its responsibility in this process.25 The military also must be presented with the tools to generate options that can achieve both discipline for and rehabilitation of the offender.17,24 Indeed, the law specifies that the service secretaries shall establish a system for restoration to duty those offenders who have had sentences either remitted or suspended, including even those who have been punitively discharged.47 Senior military leaders must publicly and aggressively make rehabilitative justice a top priority within the military services. Individualized sentencing and suspensions of discharge and confinement to permit treatment of operational stress embody a rehabilitative ethic that ultimately benefits the service member, his or her family, and society at large. Moreover, leadership is especially needed during the reduction in force that is now under way. Public safety will be further affected by the current effort to reduce 80 000 troops from the active forces by 2017 and the service secretaries’ corresponding efforts to increase the consequences for even minor infractions.48

The following options could form a beginning agenda:

Have Congress or the president dictate specific rules for addressing misconduct by service members with mental illnesses, such as bars on punitive discharges in certain cases.

Change VA regulations to permit health care treatment of combat-related mental illness regardless of discharge characterization.

Centrally adjudicate and track VA character of service claims to ensure standards are more predictable for commanders and discharged service members.

Provide commanders with more options and use military leadership to emphasize alternatives.

Make Veterans Treatment Courts and other diversionary programs more accessible to active-duty commanders through innovative partnerships and extra funding for this purpose from the federal government.

Importantly, to understand the effect of less-than-honorable discharges and negative health and societal consequences, systematic follow-up of veterans who are ineligible for VA care is necessary. Community sociodemographic, epidemiological, and treatment data identifying veterans and their military discharges are lacking; these data could make a valuable public health research contribution. Many questions raised here need better answers, and the American public health community can help cross the military-civilian divide by providing needed evidence about community effects and by demanding that policymakers use such evidence to address the issue systematically. A starting point is sensitizing the public health community to document an individual’s military service. Three A’s can form this process: (1) ask whether the individual has served in the US military, (2) assess discharge status and refer to VA to determine benefits eligibility, and (3) advocate for ineligible veterans for VA policy changes to cover such veterans with military-based health and mental health issues. Without public health oversight of this issue, expedient military justice will continue to generate a hidden cost of combat to be borne by the public for generations to come.

References

- 1.Coll JE, Weiss EL, Metal M. Military culture and diversity. In: Rubin A, Weiss EL, Coll JE, editors. Handbook of Military Social Work. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2012. pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blimes LJ. The Financial Legacy of Iraq and Afghanistan: How Wartime Spending Decisions Will Constrain Future National Security Budgets. Harvard Kennedy School: John F. Kennedy School of Government; March 2013, RWP13–006. Faculty Research Working Paper Series.

- 3.Tanielian T, Jaycox LH, editors. Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences and Services to Assist Recovery. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Army. Army 2020: Generating Health and Discipline in the Force Ahead of the Strategic Reset. Washington, DC: Headquarters, US Army; 2012. Report 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mumola CJ. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2000. Veterans in prison or jail. NCJ 178888. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mumola CJ, Noonan ME. Justice-involved veterans: national estimates. In: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, presentation: VHA National Veterans Justice Outreach Planning Conference; December 2008; Baltimore, MD.

- 7.Noonan ME, Mumola CJ. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2004. Veterans in state and federal prison. 2007. NCJ 217199. [Google Scholar]

- 8. JMAT-7 Joint Mental Health Advisory Team 7- Feb 2011 Operation Enduring Freedom 2010 Afghanistan Office of the Surgeon General, United States Army Medical Command and Office of the Command Surgeon, HQ, USCENOM and Office of the Command, US Forces Afghanistan. USFOR-A; 2011. Available at: http://armylive.dodlive.mil/index.php/2011/05/joint-mental-health-advisory-team-vii-j-mhat-7-report. Accessed July 8, 2014.

- 9.Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA . Trauma and the Vietnam War Generation: Report of Findings From the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews B, Brewin CR, Philpott R, Stewart L. Delayed-onset posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1319–1326. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacManus D, Dean K, Jones M et al. Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a data linkage cohort study. Lancet. 2013;381(9870):907–917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuehn BM. Soldier suicide rates continue to rise. JAMA. 2009;301(11):1111–1113. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan MS, Huguet N, McFarland BH, Newsom JT. Suicide among male veterans: a prospective population based study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:619–624. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.054346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sreenivasan S, Garrick T, McGuire J, Smee DE, Dow D, Woehl D. Critical issues in Iraq/Afghanistan War veterans-forensic interface part 2: nexus between combat-related post-deployment criminal violence and use of a post-deployment criminal violence rating guide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2013;41:263–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Booth-Kewley S, Highfill-McRoy RM, Larson LE, Garland CF. Psychosocial predictors of military misconduct. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(2):91–98. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc45e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. United States Code of Military Justice, 64 Stat 109, 10 USC, ch 47.

- 17.Brooker JW, Seamone ER, Rogall LC. Beyond “T.B.D.”: understanding VA’s evaluation of a former servicemember’s benefit eligibility following involuntary or punitive discharge from the armed forces. Mil Law Rev. 2012;214(Winter):1–328. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Military justice fact sheets. 2013. Available at: http://www.hqmc.marines.mil/Portals/135/MJFACTSHTS%5B1%5D.html. Accessed June 30, 2013.

- 19. US Department of Army Reg. 600-20. Army Command Policy. Rev ed. Washington, DC: Department of the Army. September 20, 2012:23. Available at: http://www.apd.army.mil/pdffiles/r600_20.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2014.

- 20. Seamone ER: Practical and historical considerations implementing regulatory bars for “moral turpitude” and “willful and persistent misconduct.” Presentation at: Board of Veteran’s Appeals Grand Rounds; August 9, 2012; Washington, DC.

- 21. Department of Veterans Affairs. Eligibility determination. In: VHA Handbook 1601A.02. November 5, 2009. Available at: http://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2113. Accessed June 30, 2013.

- 22.US Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces. Annual Reports of the Code Committee on Military Justice. Washington, DC: US Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces; pp. 2001–2011. Available at: http://www.armfor.uscourts.gov/newcaaf/ann_reports.htm. Accessed July 8, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baskir LM, Strauss W. New York, NY: Alfred A Knopf; 1978. Chance and Circumstance: the Draft, the War, and the Vietnam Generation; p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seamone ER. Reclaiming the rehabilitative ethic in military justice: the suspended punitive discharge as a method to treat military offenders with PTSD and TBI and reduce recidivism. Mil Law Rev. 2011;208(Summer):1–212. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seamone ER. Dismantling America’s largest sleeper cell: the imperative to treat, rather than merely punish, active duty offenders with PTSD prior to discharge from the armed forces. Nova Law Rev. 2013;37(3):479–522. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapman TM. Leave no soldier behind: ensuring access to health care for PTSD-afflicted veterans. Mil Law Rev. 2010;204(Summer):1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeglin DE. Veterans’ Disability Benefits Commission, Honoring the Call to Duty: Veteran’s Disability Benefits in the 21st Century. Vol. 2007. Washington, DC: Veterans’ Disability Benefits Commission; Character of discharge: legal analysis; pp. 92–96. Available at: http://www.tricare.mil/tma/ocmo/download/Exec_Summary/ES-9_HonoringCallDuty_VADisabilityBenefitCommission.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28. US Department of Army. Reg 635–200, Active Duty Enlisted Separation, 6 June 2005.

- 29.Schaller B. Veterans on Trial: The Coming Battles Over PTSD. Washington, DC: Potomac Books; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Returning Home From Iraq and Afghanistan: Assessment of Readjustment Needs of Veterans, Service Members, and Their Families. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNamara D. PTSD rates in army families surpass those of veterans. Clinical Psychiatry News. 2010;38(3):12. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandra A, Lara-Cinisomo S, Jaycox L et al. Children on the homefront: the experience of children from military families. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):16–25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chandra A, Martin L, Hawkins S, Richardson A. The impact of parental deployment on child social and emotional functioning: perspectives of school staff. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(3):218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seamone ER. Improved assessment of child custody cases involving combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Fam Court Rev. 2012;50(2):310–343. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lara-Cinisomo S, Chandra A, Burns RM et al. A mixed-method approach to understanding the experiences of non-deployed military caregivers. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(2):374–384. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dekel R, Goldblatt H. Is there intergenerational transmission of trauma? The case of combat veterans’ children. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(3):281–289. doi: 10.1037/a0013955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curtis GC, Nygaard RL. Crime and punishment: is “justice” good public policy? J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2008;36(3):385–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nygaard RL. The dawn of therapeutic justice. In: Fishbein DH, editor. Science, Treatment, and Prevention of Antisocial Behavior: Applications to the Criminal Justice System. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute Inc; 2000. 23-1 to 23–18. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burger WE. Reflections on the adversary system. Valparaiso Law Rev. 1993;27(2):309–331. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell RT. Veteran treatment court: a proactive approach. N Engl J Crim Civ Confin. 2009;35:357–372. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark S, McGuire J, Blue-Howells J. Development of Veterans Treatment Courts: local and legislative initiatives. Drug Court Rev. 2010;VII(I):171–208. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blue-Howells JH, Clark SC, van den Berk-Clark C, McGuire JF. The US Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Justice programs and the sequential intercept model: case examples in national dissemination of intervention for justice-involved veterans. Psychol Serv. 2013;10(1):48–53. doi: 10.1037/a0029652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGuire J, Clark S, Blue-Howells J, Coe C. An Inventory of VA Involvement in Veterans Courts, Dockets and Tracks. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration Veterans Justice Programs; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smee DE, McGuire J, Garrick T, Sreenivasan S, Dow D, Woehl D. Critical concerns in the Iraq/Afghanistan War veteran-forensic interface: veterans treatment court as diversion in rural communities. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2013;41:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. United Nations General Assembly. Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development: Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. August 12, 1992. Available at: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/conf151/aconf15126-1annex1.htm. Accessed September 1, 2013.

- 46.Seamone ER. The Precautionary Principle as the Law of Planetary Defense: achieving the mandate to defend the Earth against asteroid and comet impacts while there is still time. Georgetown Int Environ Law Rev. 2004;17(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Military Correctional Facilities: Remission or Suspension of Sentence. 10 USC ch 48 §953 (2006).

- 48.Philpott T. Army, marines to shield quality in 80,000-force drawdown. October 12, 2012. Available at: http://www.jdnews.com/news/military/army-marines-to-shield-quality-in-80-000-force-drawdown-1.28195. Accessed July 8, 2014.