Abstract

Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption is linked to increased weight and obesity in children and remains the major source of added sugar in the typical US diet across all age groups. In an effort to improve the nutritional offerings for patients and employees within our institution, Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, implemented an SSB ban in 2011 in all food establishments within the hospital. In this report, we describe how the ban was implemented. We found that an institutional SSB ban altered beverage sales without revenue loss at nonvending food locations. From a process perspective, we found that successful implementation requires excellent communication and bold leadership at several levels throughout the hospital environment.

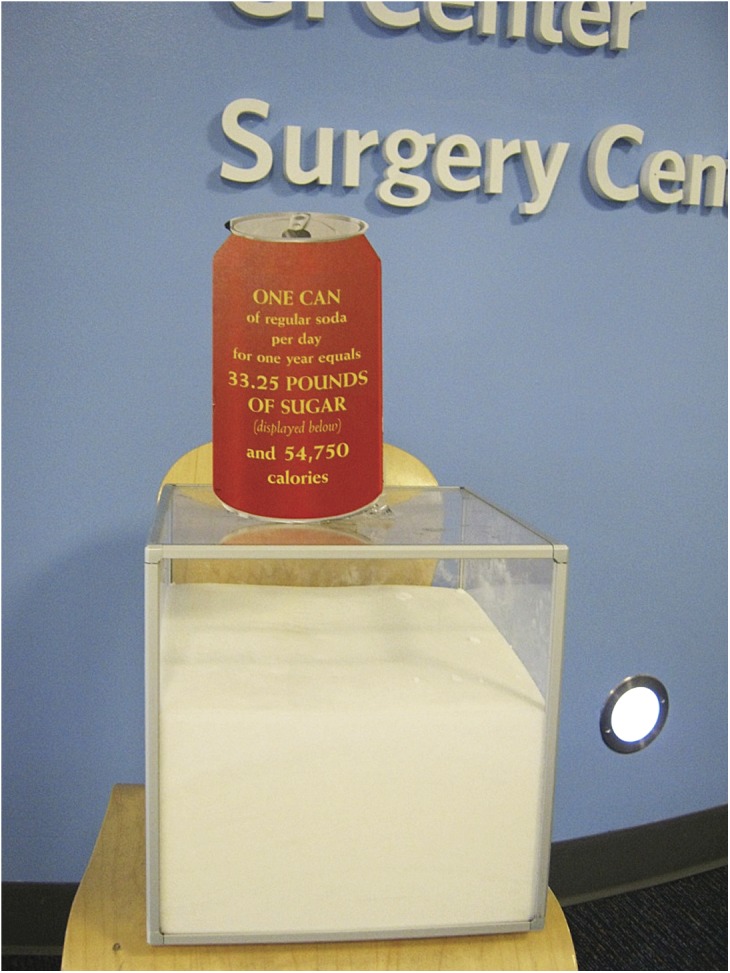

Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption is linked to increased weight and obesity in children and remains the major source of added sugar in the typical US diet across all age groups.1 For the purposes of this report, we define SSBs as soft drinks (soda or pop), fruit drinks, sports drinks, energy drinks, and any other beverages to which sugar, typically high fructose corn syrup or sucrose (table sugar), has been added.2 Although recent studies indicate an overall trending down of SSB intake, higher rates of consumption occur among low-income and minority children.1

In 2010 the Ohio legislature passed the Healthy Choices for Healthy Children Act to help schools play an active role in decreasing the high childhood obesity rates.3 A component of this law includes an SSB ban in schools. In an effort to recognize the importance of and support this statewide initiative, Nationwide Children’s Hospital (NCH) partnered with leaders in the business community to gain bipartisan support for this legislation. To further emphasize support, NCH decided to lead by example and expand the hospital’s already existing Wellness Initiative to improve the nutritional offerings for patients and employees through implementation of an SSB ban in all food establishments within the hospital and approved catering companies. Such a ban would not only impact the food environment for children but also their families as well as hospital staff. In this report, we describe our implementation of an organizational SSB ban and report the beverage consumption and sales revenue for the years preceding and following the ban, as well as key steps to implementation.

IMPLEMENTING THE SUGAR-SWEETENED BEVERAGE BAN

Based on the strategic goals of the NCH Wellness Initiative, the hospital embarked on a plan to improve the food environment. Between 2009 and 2010, healthier food and snack choices were introduced, nutrition facts displayed in the cafeteria, portion sizes of entrées and snacks reduced, and all fryers replaced by convection ovens. A “stoplight nutrition grading system” was used to indicate healthier items and encourage healthy choices. Healthier options replaced high-calorie, high-fat impulse items located at the cash registers.

As part of this effort, physician and nutrition advocates proposed a hospital-wide SSB ban to the Chief Operating Officer. This led to the establishment of a committee made up of representatives from medical staff, clinical nutrition, marketing, nursing, retail operations, family advisory council, and the hospital’s obesity center. Following a literature review and communications with other hospitals, public health officers, and health administrators, the committee developed a stepwise implementation plan (see the box on this page). This included an extensive communications campaign to obtain buy-in from hospital employees, patients, and families. The campaign, organized by NCH marketing staff, included an intranet video, strategic and weekly employee e-mail and meetings, flyers, posters (Figure 1), education tables in the food court and cafeteria, and handouts with patient meal deliveries. Media stories were strategically placed in the community including a local news story highlighting the ban with a patient who had successfully eliminated SSBs.

FIGURE 1—

Example of marketing material for the sugar-sweetened beverage ban.

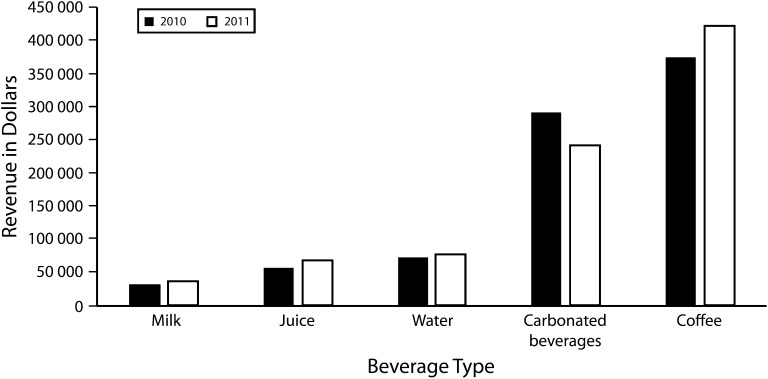

Note. Hospital owned venues include gift shops and cafeterias. Milk includes skim plain, 1% plain, low-fat chocolate, and whole milk. Juice includes only 100% fruit juice. Carbonated beverages include sugar-sweetened and diet beverages in 2010 and only diet beverages in 2011. Coffee includes specialty drinks (e.g., lattes, cappuccinos). Twenty-ounce coffees were sold in 2010, and in 2011 only sizes smaller than 20 oz were sold.

Hospital vendors signed a contract that excluded the sale of SSBs commencing in 2011. The ban was a natural continuation of the hospital’s wellness efforts, and because vendors were familiar and supportive of the hospital’s wellness initiative, they did not present an obstacle for implementation. Clinicians were allowed to request SSBs for patients if deemed necessary by placing an order in the chart, and visitors and staff could bring in SSBs to the hospital.

Key Steps in Implementing a Children's Hospital Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) Ban

| ▪ Communicate in advance of the changes to let people know the changes are coming and why |

| ▪ Use many different forms of communication including the employee intranet, flyers, internal and external newsletters and magazine, e-mail communication, and media |

| ▪ Obtain buy-in from senior level administrators and key stakeholders |

| — Executive suite |

| — Family advisory council (includes patients and families) |

| — Human resources |

| — General services/facilities |

| — Key physician stakeholders |

| — Nursing |

| ▪ Identify key champions (including employees, patients, and hospital leadership) to promote the change |

| ▪ Engage the frontline cafeteria workers early in the process because they will get a lot of the verbal feedback |

| ▪ Set up an e-mail address and suggestion box to direct comments/feedback |

| ▪ Organize opportunities to continue to engage the employees and families after the SSB ban has been implemented |

| ▪ Establish metrics that can be used to track the outcome of the SSB ban |

Nutrition Services started reducing orders in December 2010 and ran out of soda in the fountains during the last week of December. Soda vendors also let us return any unopened cases of product. The campaign culminated in January 2011 when SSBs were removed from all hospital-owned (hospital cafeteria, a food court, coffee shop, and 2 gift shops) and contracted food service venues (a franchise sandwich shop, an Asian restaurant, and vending machines). Only diet varieties of carbonated beverages, Vitamin Water, PowerAde and 100% fruit juices were allowed. Skim plain, 1% plain, low-fat chocolate milk, and whole milk remained. The latter was kept in recognition of the needs of children younger than 2 years. In addition, large (20 oz) coffee options were removed and the price of bottled water was lowered by $0.10.

TABLE 2—

Annual Beverage Sales Revenue at Hospital Contracted Locations: Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH, 2010–2011

| Beverage Sales Revenue |

|||

| Contracted Food Location | 2010, $ | 2011, $ | % Change |

| Asian restaurant | 30 913.60 | 47 461.69 | 53.5 |

| Franchise sandwich restaurant | 208 217.48 | 214 798.08 | 3.2 |

| Vending machines | 212 446.96 | 165, 886.54 | –21.9 |

| Total | 451 578.04 | 428 146.31 | –5.2 |

Beverage sales data from all food service locations were tracked from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2010 (before the ban), and from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2011 (after the ban). Data were categorized by (1) type of beverage for hospital-owned food venues and (2) location of sales for hospital contracted food venues.

FINDINGS

Compared with 2010, the total annual beverage sales at the hospital-controlled food venues (cafeteria, food court, gift and snack shops) increased by 2.7% in 2011 ($798 752 vs $867 853). Sales revenue increased by 19% for all types of milk, 22% for 100% fruit juice, 13% for coffee (includes specialty drinks such as lattes and cappuccinos), and 7% for water, while decreasing by 17% for carbonated beverages (only diet beverages in 2011; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Percent change in sales by beverage type at hospital-owned food locations after the sugar sweetened beverage (SSB) ban.

Revenue at food-contracted venues differed by location (Table 1). A decrease in beverage sales (21.9%) was observed in the vending machines during this same time period. The committee received 11 documented complaints from employees and patients about the inconvenience of obtaining SSBs and large size coffee drinks outside the hospital and concerns about stifling an individual’s free choice. These complaints were handled individually.

EVALUATION

An institutional policy banning SSBs at NCH altered beverage sales in 12 months without revenue loss at nonvending food locations. Beverage sales patterns shifted with a decrease in carbonated beverages and an increase in milk, juice, water, and coffee sales. Decreasing the price for bottled water may have contributed to the increase seen, while eliminating the 20-ounce coffee did not affect sales negatively. The decrease in vending machine revenue cannot be solely attributed to the ban; in 2011 the vending company increased beverage prices by $0.35, a change planned well ahead of the ban. Consumer behavior is influenced by environmental and marketing factors as well as the situation, personal and psychological factors, family, and culture.4 Based on the data we have available to us, we cannot determine the causes for the observed purchasing behavior.

There are additional limitations to our evaluation. We were unable to examine differences in sales among hospital owned venues (gift shops and cafeterias). We were also unable to separate milk types by revenue, track when SSBs were prescribed by the medical staff, identify when SSBs were brought into the premises by staff or families, or examine the sales of SSBs at stores near the hospital.

CONCLUSIONS

Our experience demonstrates that a SSB ban is not onerous to institute, particularly if implemented within a broader wellness initiative that includes healthier food options and a strong employee wellness program. Our experience has served as a resource for several hospitals and institutions interested in adopting similar policies. We plan to continue tracking sales revenue over time to better assess changes in consumption related to buying patterns.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Rosara Milstein and Brook Belay for their help with this project.

Human Participant Protection

Human participant protection was not required because this was not deemed human subjects research.

References

- 1.Slining MM, Mathias KC, Popkin BM. Trends in food and beverage sources among US children and adolescents: 1989-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.06.001. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC Guide to Strategies for Reducing the Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. Available at http://www.cdph.ca.gov/SiteCollectionDocuments/StratstoReduce_Sugar_Sweetened_Bevs.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2014.

- 3. Ohio Legislative Service Commission. S.B. 210. 130th General Assembly. Available at: http://www.lsc.state.oh.us/analyses130/s0210-i-130.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2014.

- 4.Tanner JF, Raymond MA. Principles of Marketing. Available at: http://catalog.flatworldknowledge.com/bookhub/reader/5229?e=fwk-133234-ch03_s01. Accessed February 28, 2014.