Abstract

Most mammalian chloride channels and transporters in the CLC family display pronounced voltage-dependent gating. Surprisingly, despite the complex nature of the gating process and the large contribution to it by the transport substrates, experimental investigations of the fast gating process usually produce canonical Boltzmann activation curves that correspond to a simple two-state activation. By using nonlinear capacitance measurements of two mutations in the ClC-5 transporter, here we are able to discriminate and visualize discrete transitions along the voltage-dependent activation pathway. The strong and specific dependence of these transitions on internal and external [Cl−] suggest that CLC gating involves voltage-dependent conformational changes as well as coordinated movement of transported substrates.

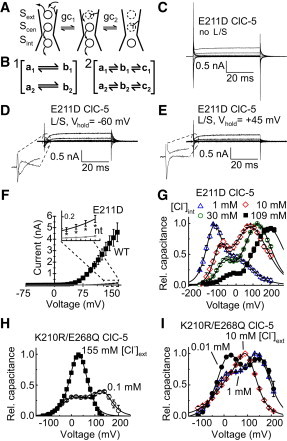

The chloride channel (CLC) family is divided into ion channels and secondary active Cl−/H+ antiporters. The majority of the mammalian CLC isoforms demonstrate pronounced voltage-dependent gating that is important for their physiological function. Some of the transporter isoforms display gating currents and nonlinear capacitances (1–4) that are related to voltage-dependent activation of CLC transport and reflect charge movements within the transmembrane electric field. Although the molecular mechanisms underlying these charge movements are still obscure, it is well established that a conserved glutamate residue at the extracellular side of the protein (Gluext) is a key player that regulates CLC gating. Neutralization of this residue leads to dramatic changes of the voltage dependence in CLC transporters as well as in CLC channels (1,5–9). The available CLC crystal structures show that Gluext can occupy two out of the three distinct anion binding sites in the CLC anion selectivity filter—the outer (Sext) and the central (Scen) binding sites (10,11)—both of which seem to be situated within the transmembrane electric field (Fig. 1 A).

Figure 1.

Cl−-dependent biphasic capacitances of E211D and K210R/E268Q. (A) Schematic representation of the movement of Gluext during the transport cycle of ClC-5. The hypothetical gating charge movement (gc) includes the initial occupation of the external Cl− binding site Sext by the gating glutamate and the simultaneous unbinding of one internal Cl− ion (gc1). The second step (gc2) in the gating sequence consists of the movement of the gating glutamate to the central Cl− binding site Scen and a second unbinding of an internally bound Cl−. (B) Provisional ClC-5 gating schemes with either two independent parallel two-state (panel 1) or three-state (panel 2) gating charge transitions. (C) Representative whole-cell recording of a HEK293T cell expressing E211D ClC-5 upon voltage pulses between −115 and +165 mV. (D and E) The same cell as in C recorded using P/N subtraction with a leak-holding potential of −60 mV (D) or +45 mV (E). (Insets) Effects of the leak-holding potential on the appearance of E211D gating currents. Shown are only two traces at the most extreme voltages. (F) Averaged current amplitudes of nontransfected (nt) HEK293T cells or cells expressing wild-type (WT) or E211D ClC-5 (n = 7–9). (Inset) Region between +135 and +165 mV (with asterisks indicating significant differences, two-sample t-test, p < 0.01). (G) Nonlinear capacitances of E211D ClC-5 at 155 mM extracellular [Cl−] and various internal [Cl−]. (Solid lines) Fits with a sum of two capacitance functions (see Eq. S2 in the Supporting Material) (n = 4–7). (H) Averaged nonlinear capacitances of four HEK293T cells expressing K210R/E268Q ClC-5 at 30 mM [Cl−]int, first measured in presence of 155 mM (solid squares) and then of 0.1 mM [Cl−]ext (open circles). Normalization was performed to the maximum capacitance in 155 mM [Cl−]ext. (Solid lines) Fits to the sum of two capacitance functions. (I) Nonlinear capacitances of cells expressing K210R/E268Q ClC-5 measured separately at different [Cl−]ext concentrations and 30 mM [Cl−]int. Normalization was performed to the maximum capacitance at each particular [Cl−]ext. (Solid lines) Fits to the sum of two capacitance functions (n = 5).

The structure of a “protonated” E-to-Q gating glutamate mutant reveals a third stable conformation in which Gluext is in the extracellular solution outside of the protein. These structures suggest the existence of a significant energy barrier separating Sext and Scen (10,11). It is therefore rational to expect that the sequential movement of Gluext from its extracellular position toward Sext and Scen should result in at least two discrete voltage-dependent steps (Fig. 1 A). In contrast, fast gating of CLC proteins is fairly described by a canonical Boltzmann function corresponding to a simple two-state gating scheme. Nonlinear capacitances of WT ClC-5 tested under various ionic conditions also do not exhibit pronounced multiphasic behavior (2,4) (see Fig. S5 A and Fig. S7 A in the Supporting Material).

To resolve individual gating transitions along the activation pathway of ClC-5, we mutated the gating glutamate Gluext to aspartate (mutation E211D ClC-5). Analogous mutations were reported by other groups to dramatically shift voltage-dependence of gating currents in ClC-5 (3) and to decelerate coupled transport in EcCLC (12). The latter effect has been explained by proposing an energetic penalty for the shorter aspartate side chain to reach all the way down to Scen (12). We hypothesized that such a penalty might also better separate the discrete steps in the activation of ClC-5. Whole-cell patch-camp recordings of E211D ClC-5 revealed small but well-distinguishable ionic currents (Fig. 1, C and F), demonstrating that the mutant is capable of mediating electrogenic transport albeit with reduced amplitudes. Surprisingly, standard P/N leak subtraction produced confusing results with gating currents that strongly depended on the holding potential of the leak subtraction sequence (Fig. 1, D and E).

These observations cannot be reconciled with a simple left-shift of the voltage-dependence of E211D as reported previously by Zifarelli et al. (3), but instead suggest that the mutant exhibits gating currents in a very broad range of voltages. To resolve this inconsistency, we performed nonlinear capacitance measurements. The procedure revealed two distinct peaks in the capacitance-voltage curve (Fig. 1 G), reflecting the existence of at least two discrete steps in the voltage dependence of E211D ClC-5. As a consequence, P/N leak correction might subtract ionic currents, as well as gating currents mediated by this mutant (Fig. 1, D and E, insets). To further investigate the behavior of E211D ClC-5, we decreased internal [Cl−] (Cl−int) and described the data with a general model consisting of two parallel independent gating charge movements, which is a sum of two independent capacitance functions (Fig. 1 B, panel 1, and see Eq. S2 and Table S1 in the Supporting Material).

Lowering [Cl−]int shifted both peaks of the capacitance curve toward hyperpolarized voltages and progressively increased the amplitude of the lower-voltage peak relative to that of the higher-voltage peak (Fig. 1 G, and see Fig. S1 A, Fig. S2 A, and see Fig. S3 A). These effects indicate further that individual gating steps along the activation of ClC-5 are specifically affected by the interactions with the transport substrate.

To exclude that biphasic gating is characteristic only for E211D, we next investigated mutation K210R, which is adjacent to Gluext 211; K210R has also been reported previously to alter voltage-dependent gating, substrate specificity, rectification, and alkaline response in various CLCs (5,13,14). To maximize nonlinear capacitances, we additionally mutated the proton glutamate E268 to glutamine, a maneuver that silences coupled transport but preserves voltage-dependent gating (1,2). The left-shifted voltage dependence of mutant K210R (see Fig. S5) enabled experiments at reduced external [Cl−] for which the activation of ClC-5 occurs at more depolarized voltages (1,2). The nonlinear capacitances of K210R/E268Q ClC-5 in external solution containing 155 mM [Cl−] exhibited the usual bell-shaped form (Fig. 1 H). Reducing extracellular [Cl−] led, however, to the appearance of two distinct capacitance peaks (Fig. 1 H, and see Table S2; for the transporting mutant K210R, see Fig. S5 D).

Similarly to E211D, the [Cl−] dependence of K210R included a shift of the overall voltage dependence as well as changes in the relative amplitudes of both capacitance peaks (Fig. 1 I, and see Fig. S1 B, Fig. S2 B, and see Fig. S3 B). We noted that the integral of the nonlinear capacitance over the voltage provides the amount of mobile charges that contribute to the polarization of the dielectric medium. Changing external [Cl−] at the same cell revealed nearly identical values for the apparent gating charge in the presence or absence of Cl− (Fig. 1 H), indicating that external anions very weakly (if at all) contribute to the gating charge underlying ClC-5 gating. As a consequence and in contrast to mutation E211D, the behavior of K210R/E268Q could be described by a sequential three-step gating scheme with charge preservation (upper line in Fig. 1 B, panel 2, and see Fig. S4), which has been used previously to model nonlinear capacitances of the cochlear motor protein prestin (15).

For mutation K210R/E268Q, we also investigated how the apparent amplitudes of the nonlinear capacitances depend on the experimental lock-in frequency (see Fig. S7, A–C). Standard Debye description of this dependence (16) showed that the mutant exhibits a much faster characteristic polarization time constant (∼80 vs. ∼230 μs for E268Q ClC-5, see Table S6), which points at accelerated gating charge kinetics. This conclusion was confirmed by the faster time constants of charge mobilization alternatively measured using envelope protocols (see Fig. S7, D and E).

We here report the behavior of two point mutations in the anion/proton exchanger ClC-5 that both display two separate peaks in their voltage-dependent nonlinear capacitances. Such discretization is predicted by existing models of the CLC transport cycle (summarized in Fig. 1 A) (11,17). However, it has never been documented experimentally until now. The vast majority of the published data are based on tail current or gating charge analysis (see Fig. S5 C) and may represent a smoothed sum of multiple Boltzmann functions for which transitions with similar voltage dependences cannot be easily separated (18) (see Fig. S6). Because, however, nonlinear capacitances correspond to the first derivative of the moved gating charge, the midpoint of activation translates into a peak in the capacitance-voltage curve and is therefore more sensitive to dissect complex gating into separate voltage-dependent steps. This allowed us to demonstrate that voltage-dependent activation of mammalian CLC transporters (and by analogy probably also fast gating of CLC channels) involves at least two discrete voltage-dependent conformational transitions.

The lack of an established gating model allows postulating only a provisional mechanism for the behavior of the investigated mutants. We hypothesize that the discrete voltage-dependent steps correspond to the transition of Gluext between the external medium and the binding sites Sext and Scen (Fig. 1 A). The functional phenotype of mutation K210R can be described by a sequential three-state model (Fig. 1 B) (15), suggesting that external anions are not electrostatically equivalent to the side chain of Gluext and contribute weakly to the gating charge of ClC-5.

Accordingly, the biphasic capacitances of mutant K210R at low [Cl−]ext might be explained by subtle conformational changes that alter the affinity of Gluext for binding at Sext. Another significant part of the ClC-5 gating charge might be contributed by anion binding/unbinding reactions at the internal site Sint. This notion is supported by the failure of a sequential three-state gating scheme to describe the capacitances of E211D at higher [Cl−]int. We found the simplest suitable model with a larger degree of freedom to be a generalized scheme with two independent gating steps (Fig. 1 B, panel 1). Extending this model to cover the behavior of mutation K210R would result in two parallel branches consisting of sequential three-state transitions (Fig. 1 B, panel 2) that are discriminated by the absence or presence of Cl− at Sint.

In summary, the effects of mutations E211D and K210R on the voltage dependence of ClC-5 may be encountered for by a hypothetical model with a derailed CLC gating sequence in which the altered movement of Gluext is no longer well synchronized with the voltage-dependent binding/unbinding of internal Cl− at Sint.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Martin Fischer for fruitful discussions.

Supporting Material

References and Footnotes

- 1.Smith A.J., Lippiat J.D. Voltage-dependent charge movement associated with activation of the CLC-5 2Cl−/1H+ exchanger. FASEB J. 2010;24:3696–3705. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-150649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grieschat M., Alekov A.K. Glutamate 268 regulates transport probability of the anion/proton exchanger ClC-5. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:8101–8109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.298265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zifarelli G., De Stefano S., Pusch M. On the mechanism of gating charge movement of ClC-5, a human Cl−/H+ antiporter. Biophys. J. 2012;102:2060–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guzman R.E., Grieschat M., Alekov A.K. ClC-3 is an intracellular chloride/proton exchanger with large voltage-dependent nonlinear capacitance. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013;4:994–1003. doi: 10.1021/cn400032z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fahlke Ch., Yu H.T., George A.L., Jr. Pore-forming segments in voltage-gated chloride channels. Nature. 1997;390:529–532. doi: 10.1038/37391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Picollo A., Pusch M. Chloride/proton antiporter activity of mammalian CLC proteins ClC-4 and ClC-5. Nature. 2005;436:420–423. doi: 10.1038/nature03720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheel O., Zdebik A.A., Jentsch T.J. Voltage-dependent electrogenic chloride/proton exchange by endosomal CLC proteins. Nature. 2005;436:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nature03860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X., Wang T., Weinman S.A. The ClC-3 chloride channel promotes acidification of lysosomes in CHO-K1 and Huh-7 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C1483–C1491. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00504.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neagoe I., Stauber T., Jentsch T.J. The late endosomal ClC-6 mediates proton/chloride countertransport in heterologous plasma membrane expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:21689–21697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.125971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutzler R., Campbell E.B., MacKinnon R. Gating the selectivity filter in ClC chloride channels. Science. 2003;300:108–112. doi: 10.1126/science.1082708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng L., Campbell E.B., MacKinnon R. Structure of a eukaryotic CLC transporter defines an intermediate state in the transport cycle. Science. 2010;330:635–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1195230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng L., Campbell E.B., MacKinnon R. Molecular mechanism of proton transport in CLC Cl−/H+ exchange transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:11699–11704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205764109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludewig U., Jentsch T.J., Pusch M. Inward rectification in ClC-0 chloride channels caused by mutations in several protein regions. J. Gen. Physiol. 1997;110:165–171. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Stefano S., Pusch M., Zifarelli G. Extracellular determinants of anion discrimination of the Cl−/H+ antiporter protein CLC-5. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:44134–44144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.272815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Homma K., Dallos P. Evidence that prestin has at least two voltage-dependent steps. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:2297–2307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.185694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández J.M., Bezanilla F., Taylor R.E. Distribution and kinetics of membrane dielectric polarization. II. Frequency domain studies of gating currents. J. Gen. Physiol. 1982;79:41–67. doi: 10.1085/jgp.79.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller C., Nguitragool W. A provisional transport mechanism for a chloride channel-type Cl−/H+ exchanger. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009;364:175–180. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bezanilla F., Villalba-Galea C.A. The gating charge should not be estimated by fitting a two-state model to a Q-V curve. J. Gen. Physiol. 2013;142:575–578. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.