Abstract

Background

Antiepileptic drugs have been used in pain management since the 1960s. Pregabalin is a recently developed antiepileptic drug also used in management of chronic neuropathic pain conditions.

Objectives

To assess analgesic efficacy and associated adverse events of pregabalin in acute and chronic pain.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL to May 2009 for randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Additional studies were identified from the reference lists of retrieved papers and on-line clinical trial databases.

Selection criteria

Randomised, double blind trials reporting on the analgesic effect of pregabalin, with subjective pain assessment by the patient as either the primary or a secondary outcome.

Data collection and analysis

Two independent review authors extracted data and assessed trial quality. Numbers-needed-to-treat-to-benefit (NNTs) were calculated, where possible, from dichotomous data for effectiveness, adverse events and study withdrawals.

Main results

There was no clear evidence of beneficial effects of pregabalin in established acute postoperative pain. No studies evaluated pregabalin in chronic nociceptive pain, like arthritis.

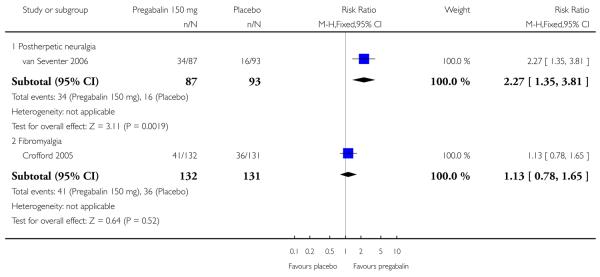

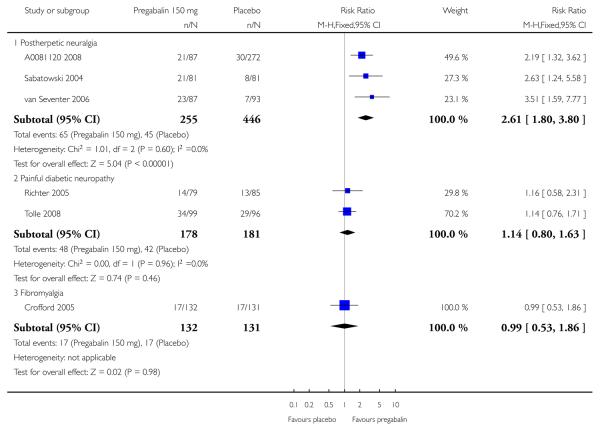

Pregabalin at doses of 300 mg, 450 mg, and 600 mg daily was effective in patients with postherpetic neuralgia, painful diabetic neuropathy, central neuropathic pain, and fibromyalgia (19 studies, 7003 participants). Pregabalin at 150 mg daily was generally ineffective. Efficacy was demonstrated for dichotomous outcomes equating to moderate or substantial pain relief, alongside lower rates for lack of efficacy discontinuations with increasing dose. The best (lowest) NNT for each condition for at least 50% pain relief over baseline (substantial benefit) for 600 mg pregabalin daily compared with placebo were 3.9 (95% confidence interval 3.1 to 5.1) for postherpetic neuralgia, 5.0 (4.0 to 6.6) for painful diabetic neuropathy, 5.6 (3.5 to 14) for central neuropathic pain, and 11 (7.1 to 21) for fibromyalgia.

With 600 mg pregabalin daily somnolence typically occurred in 15% to 25% and dizziness occurred in 27% to 46%. Treatment was discontinued due to adverse events in 18 to 28%. The proportion of participants reporting at least one adverse event was not affected by dose, nor was the number with a serious adverse event, which was not more than with placebo.

Higher rates of substantial benefit were found in postherpetic neuralgia and painful diabetic neuropathy than in central neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. For moderate and substantial benefit on any outcome NNTs for the former were generally six and below for 300 mg and 600 mg daily; for fibromyalgia NNTs were much higher, and generally seven and above.

Authors’ conclusions

Pregabalin has proven efficacy in neuropathic pain conditions and fibromyalgia. A minority of patients will have substantial benefit with pregabalin, and more will have moderate benefit. Many will have no or trivial benefit, or will discontinue because of adverse events. Individualisation of treatment is needed to maximise pain relief and minimise adverse events. There is no evidence to support the use of pregabalin in acute pain scenarios.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Acute Disease; Analgesics [administration & dosage; *therapeutic use]; Chronic Disease; Diabetic Neuropathies [drug therapy]; Fibromyalgia [drug therapy]; Neuralgia, Postherpetic [drug therapy]; Pain [*drug therapy]; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; gamma-Aminobutyric Acid [administration & dosage; *analogs & derivatives; therapeutic use]

MeSH check words: Adult, Humans

BACKGROUND

Chronic pain is usually defined as pain experienced for a period of about three to six months during which it is felt every day or almost every day. Any pain that is not chronic is acute, though there are always special circumstances, using these definitions, where either or neither are entirely satisfactory.

Chronic pain is a major health problem affecting one in five people in Europe (Fricker 2004), though data for the incidence of neuropathic pain (pain resulting from a disturbance of the central or peripheral nervous system) is more difficult to obtain. Antiepileptic drugs have been used in pain management since the 1960s, very soon after they were first used generally in medicine. The clinical impression is that they are useful for neuropathic pain (e.g. painful diabetic neuropathy, post herpetic neuralgia), especially when the pain is lancinating or burning (Jacox 1994). Although these neuropathic pain disorders are not common (with the incidence of trigeminal neuralgia being four in 100,000 per year (Rappaport 1994)), they can be very disabling.

There is evidence for the effectiveness of a number of antiepileptics including carbamazepine, gabapentin, phenytoin and valproate; these are considered in other reviews published by the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care review group (Wiffen 2005a; Wiffen 2005b; Wiffen 2005c). Antiepileptics are sometimes prescribed in combination with antidepressants, as in the treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) (Monks 1994). In the UK carbamazepine and phenytoin are licensed for the treatment of pain associated with trigeminal neuralgia, and gabapentin and pregabalin for the treatment of neuropathic pain.

The use of antiepileptic drugs in chronic pain has tended to be confined to neuropathic pain (like painful diabetic neuropathy, PDN), rather than nociceptive pain (like arthritis). However, some trials have examined the utility of this class of drugs in acute pain conditions. It is therefore probably useful to extend the scope of this first Cochrane review of pregabalin to seek studies that have been conducted in acute pain conditions. Acute pain is generally as poorly treated as chronic pain.

Pregabalin has a mechanism of action similar to gabapentin, binding to calcium channels and modulating calcium influx as well as influencing GABergic neurotransmission. This mode of action confers anti-epileptic, analgesic, and anxiolytic effects. It is more potent than gabapentin and therefore used at lower doses. Pregabalin, as Lyrica™, is licensed for the treatment of peripheral and central neuropathic pain in adults. Guidance suggests that pregabalin treatment can be started at a dose of 150 mg per day for treating neuropathic pain. Based on individual patient response and tolerability, the dosage may be increased to 300 mg per day after an interval of three to seven days, and if needed, to a maximum dose of 600 mg per day after an additional seven-day interval (EMC 2007). European approval for marketing was granted in 2004 and US approval in 2005.

This review is an extension to the published review in The Cochrane Library on ’Anticonvulsants in acute and chronic pain’ (Wiffen 2005a). Because pregabalin has been introduced within the last few years, with a number of trial reports now becoming available, a review specific to this drug is appropriate at this time.

A particular issue with pregabalin is that of dose and dose escalation with different upper limits used in different trials. In standard clinical trials there is known to be a significant dose-response (Straube 2008). Another is the possible impact of enriched enrolment on the efficacy reported in trials, although the rather small amount of partial enrichment that could occur in most trials is without any significant effect (Straube 2008). More interesting is the publication of the results of a trial with complete enrichment, randomised withdrawal (EERW) design (Crofford 2008). This is the largest, longest, and best example of this trial design in pain (McQuay 2008a), and offers a potential challenge to interpretation of clinical trial data. Dose, but not degree of enrichment, has been shown to be important for pregabalin (Straube 2008).

OBJECTIVES

To assess the analgesic efficacy of pregabalin for acute pain and for chronic pain in adults.

To assess the adverse events associated with the clinical use of pregabalin for pain.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were included in this review if they were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), reported to be double-blind, and investigating the analgesic effects of pregabalin, with pain assessment as either the primary or secondary outcome. Full journal publication or summary clinical trial reports were required, with brief abstracts not included. For chronic pain, participants were required to have had a diagnosed condition for at least three months.

Studies that were non-randomised, studies of experimental pain, case reports, clinical observations or studies of pregabalin used to treat pain produced by other drugs were excluded.

Types of participants

Adults aged 18 years or more, who:

reported pain in the acute pain setting or were studied in situations (postoperative, for example) where pain was anticipated; or

had one or more of a wide range of chronic or neuropathic pains including diabetic neuropathy, post herpetic neuralgia (PHN), phantom limb pain, Guillain Barré, and spinal cord injury;

had any other chronic painful condition.

For chronic pain the predominant presenting neuropathic pain conditions were analysed separately.

Types of interventions

Administration of pregabalin, in any dose, by any route to achieve analgesia. Studies had to include placebo control or any active control as comparisons.

Types of outcome measures

A variety of outcome measures were used in the studies. For acute pain studies we expected to identify assessment at 6 hours post-treatment. For chronic pain we expected to identify data for pain relief at two weeks, four weeks and three months. Outcomes at the end of study were used, with a four week minimum.

In chronic pain the majority of studies were expected to use standard subjective scales for pain intensity or pain relief, or both. A hierarchy of pain-related outcome measures in chronic pain was agreed as follows:

patient reported pain relief of 30% or greater;

patient reported pain relief of 50% or greater;

patient reported global impression of clinical change (PGIC);

pain on movement;

pain on rest;

any other pain related measure;

adverse effects with a sub group analysis of older people if data were available.

Particular attention was paid to IMMPACT definitions for moderate and substantial benefit in chronic pain studies (Dworkin 2008). These were defined as at least 30% pain relief over baseline (moderate), at least 50% pain relief over baseline (substantial), much or very much improved on PGIC (moderate), and very much improved on PGIC (substantial).

In acute pain the most likely outcome measure anticipated was analgesic consumption in perioperative use of pregabalin.

For both chronic and acute pain situations, various adverse event outcomes were sought:

number of participants with at least one adverse event;

number of participants with at least one serious adverse event;

number of participants experiencing particular adverse events (somnolence and dizziness);

all-cause withdrawals;

lack of efficacy withdrawals;

adverse event withdrawals.

Search methods for identification of studies

Studies were identified by several methods. RCTs of pregabalin (and key brand name: Lyrica) in acute, chronic or cancer pain were identified using:

MEDLINE (PubMed) from 1990 to May 2009;

EMBASE (Ovid) from 1990 to May 2009;

Cochrane CENTRAL, Issue 2, 2009.

Additional studies were sought from reference lists of the retrieved papers, and by searching the Internet for summary clinical trial reports not available as full publications. Given the limited literature in this area, a general search strategy was undertaken. See Appendix 1, Appendix 2, and Appendix 3 for the MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL search strategies. The PhRMA clinical study results database (www.clinicalstudyresults.org/) was interrogated for trial results of pregabalin (Lyrica) in painful conditions.

Data collection and analysis

Eligibility was determined by reading each study identified by the search. All studies were read independently by two review authors and agreement reached by discussion. The studies were not anonymised before assessment.

Information about the pain condition and number of participants treated, drug and dosing regimen, study design (placebo or active control), study duration and follow-up, analgesic outcome measures and results, withdrawals and adverse events (participants experiencing any adverse event, or serious adverse event) were extracted from each study and recorded on a data extraction sheet.

QUOROM guidelines were followed (Moher 1999). For efficacy analyses we used the number of participants in each treatment group who were randomised, received medication, and provided at least one post-baseline assessment. For safety analyses we used the number of participants who received study medication in each treatment group.

Number needed to treat to benefit (NNT) was calculated as the reciprocal of the absolute risk reduction (ARR) (McQuay 1998). For unwanted events, the NNT becomes the number needed to treat to harm (NNH), and is calculated in the same manner. Dichotomous data was used to calculate relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using a fixed-effect model. Continuous data (if available) would be entered into RevMan 5.0 using the appropriate statistic. Studies were assessed for quality using the Oxford Quality Scale (Jadad 1996). Sub group analysis was undertaken for dose of pregabalin and type of painful condition. Risk of bias tables were also completed.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

Pregabalin is a relatively new drug, and therefore searching produced a relatively modest number of titles for examination.

Included studies

Twenty five studies were included in total for this review as follows:

Six studies (649 participants; Agarwal 2008; Hill 2001; Jokela 2008a; Jokela 2008b; Mathiesen 2009; Paech 2007) studied the effects of pregabalin at various doses in perioperative situations over about 24 hours, in comparisons with placebo or an active drug (diazepam).

Nineteen studies (7003 participants) studied the effects of pregabalin in: post herpetic neuralgia (A0081120 2008; Dworkin 2003; Sabatowski 2004; Stacey 2008; van Seventer 2006), painful diabetic neuropathy (A0081071 2007; Arezzo 2008; Freynhagen 2005; Lesser 2004; Richter 2005; Rosenstock 2004; Tolle 2008), central neuropathic pain (Siddall 2006; Vranken 2008), or fibromyalgia (A0081100 2008; Arnold 2008; Crofford 2005; Crofford 2008; Mease 2008). A further study was a duplicate report in German of Freynhagen 2005. All of these compared various doses of pregabalin, using various fixed-dose or titration strategies, with placebo. Study duration was mainly between four and 14 weeks, with the exception of a longer EERW trial that lasted 26 weeks (Crofford 2008). Full details are in the ’Characteristics of included studies’ table.

Excluded studies

One study (Reuben 2006) was included initially. However, due to allegations of data fabrication from the publishing journal, we chose to exclude the data.

Risk of bias in included studies

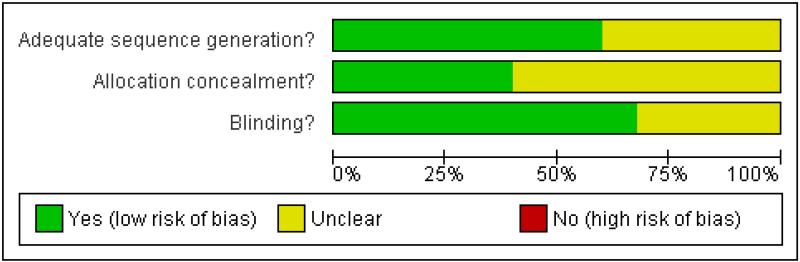

The studies all had Oxford quality scores of three or more out of the maximum of five, indicating little likelihood of methodological bias. Eleven studies scored five, eight scored four, and six scored three points. Details are in the ’Characteristics of included studies’ table. Risk of bias tables are presented (Figure 1 and Figure 2) and show risk of bias based on sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding.

Figure 1. Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2. Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

Acute pain

The six studies of pregabalin in acute pain (Agarwal 2008; Hill 2001; Jokela 2008a; Jokela 2008b; Mathiesen 2009; Paech 2007) did not present a sufficiently homogeneous group of trials to allow a pooled analysis. There were differences in types of surgery, dose of pregabalin, and whether it was used preoperatively to prevent pain or postoperatively to reduce established pain. One study was sponsored by Pfizer or Parke Davies (Hill 2001), and two were funded by a foundation (Jokela 2008a; Jokela 2008b).

Hill 2001 used a standard postoperative pain model (single dose oral therapy with pain measurements over 6 hours in participants with established moderate or severe pain) to compare single oral doses of pregabalin 50 mg and 300 mg with placebo and ibuprofen 400 mg. Participants with only mild pain were included, reducing the validity of the results because it is difficult to demonstrate pain relief if there is little pain to begin with (McQuay 2008b). Pregabalin 300 mg had similar efficacy to ibuprofen 400 mg, possibly with a slightly longer duration of action, in groups of about 50 participants each. The reported adverse event rate was much higher (68%) with pregabalin 300 mg than any other group, and two participants (4%) had serious adverse events, which is unusual for this type of study.

Paech 2007 found that 100 mg pregabalin given 1 hour before minor gynaecological surgery made no difference to postoperative pain, although most women had no pain even with placebo. Results for perioperative pregabalin given at various doses were no different from diazepam 5 mg or 10 mg over 24 hours in women undergoing laparoscopic surgery (Jokela 2008a; Jokela 2008b), although again average pain scores were generally below the level of moderate pain for most of the time. In another study, pregabalin 300 mg preoperatively with or without dexamethasone made no difference to pain scores over 24 hours; a statistically lower 24-hour morphine consumption was compromised by enormous variability in the placebo group where the 95% CI range for morphine consumption ranged from 0 mg to over 100 mg (Mathiesen 2009). One study of preoperative pregabalin (150 mg) found consistent benefit for pregabalin compared with placebo over 24 hours, in terms of measured pain at rest and on activity, together with a 26% reduction in postoperative fentanyl consumption (Agarwal 2008).

Chronic pain

Studies investigating the efficacy and safety of pregabalin compared with placebo in chronic pain were found in four neuropathic pain conditions: five studies (1417 participants) in PHN (A0081120 2008; Dworkin 2003; Sabatowski 2004; Stacey 2008; van Seventer 2006), seven studies (2086 participants) in painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN; A0081071 2007; Arezzo 2008; Freynhagen 2005; Lesser 2004; Richter 2005; Rosenstock 2004; Tolle 2008), two studies (177 participants) in central neuropathic pain (CP; Siddall 2006; Vranken 2008), and five studies (3323 participants) in fibromyalgia (A0081100 2008; Arnold 2008; Crofford 2005; Crofford 2008; Mease 2008). The total number of participants in the neuropathic pain studies and fibromyalgia was 7003. Studies were all sponsored by Pfizer or Parke Davies, except one study where no sponsorship was mentioned (Vranken 2008).

One study included both PDN and PHN; as 74% of participants had PDN, this study was classified and analysed as PDN (Freynhagen 2005). One study in fibromyalgia used complete enriched enrolment randomised withdrawal (EERW) design (Crofford 2008). This design is very different from classic randomised design which is used for the rest of the studies so its results are discussed separately (McQuay 2008a). Some studies used partial enriched enrolment, in which some patients may have been excluded by failure to respond to treatments similar to pregabalin, or included because they had responded to treatments like pregabalin. The effects of partial enriched enrolment in this circumstance has been adequately explored, and shown not to have had any effect on results (Straube 2008).

Study duration was four weeks in one study (Stacey 2008), five weeks in one study (Lesser 2004), and six weeks in another (Richter 2005). In all other studies duration was 8 to 14 weeks, with the exception of the EERW study of over 26 weeks (Crofford 2008). Results were combined irrespective of trial duration, but results of the EERW study were not included in the combined analysis. Results for pregabalin at different daily doses were compared with placebo; there were no active controlled trials. Most studies used a short titration period of one week to a fixed daily dose of pregabalin. Some (Stacey 2008, for example) used a more flexible dosing regimen, with pregabalin flexible dosing including a maximum daily dose. In the latter case, the maximum daily dose was considered the dose used. No separate analysis was undertaken for flexible versus fixed dose regimens because this would fragment the data and leave too little for sensible comparison.

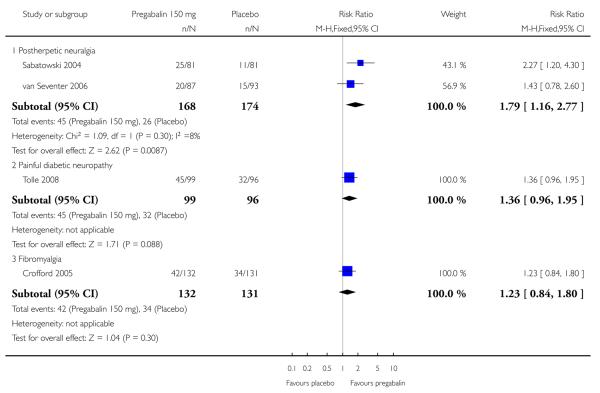

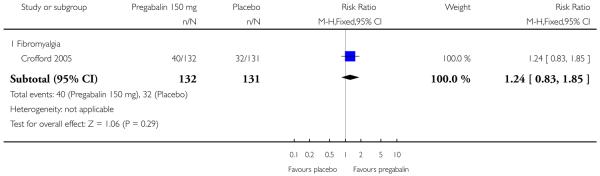

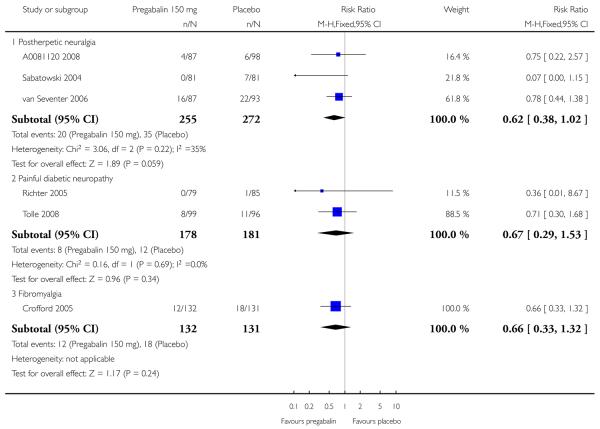

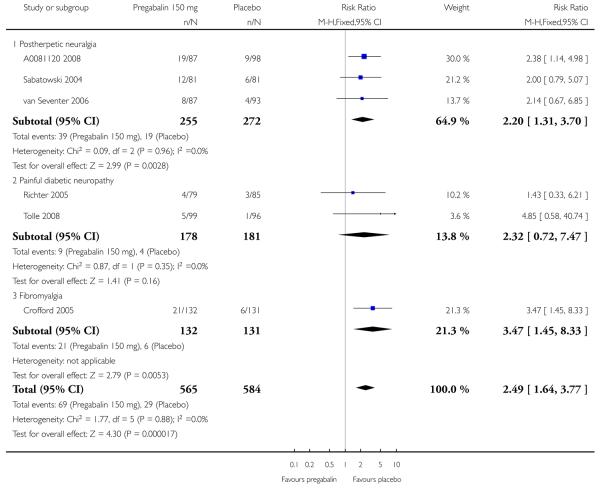

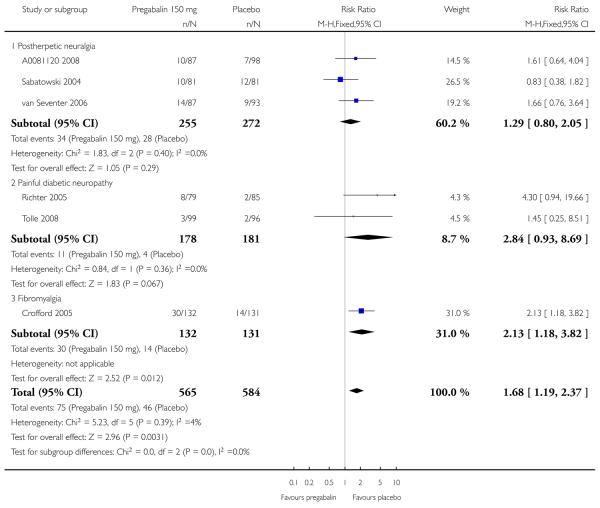

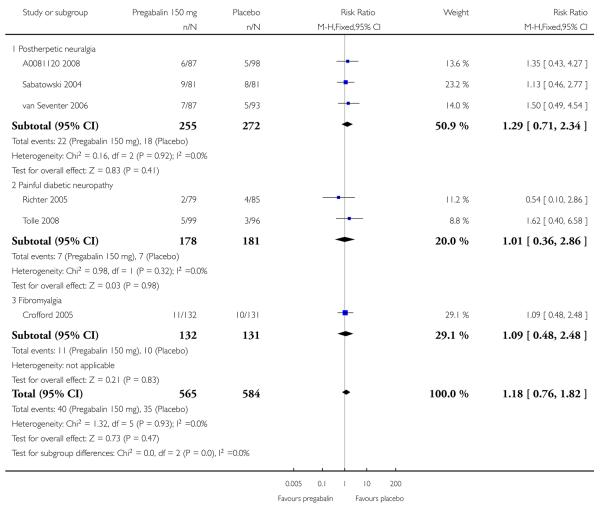

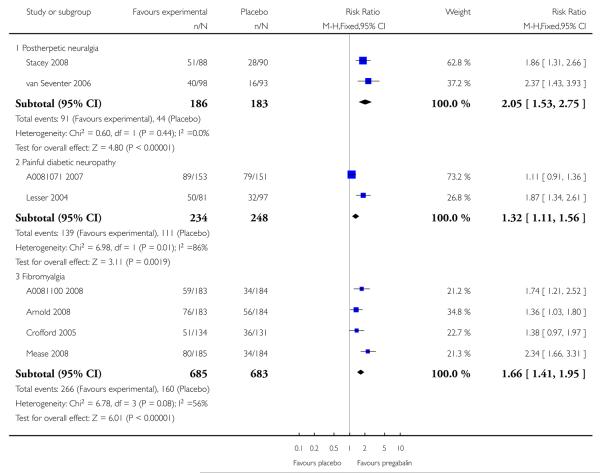

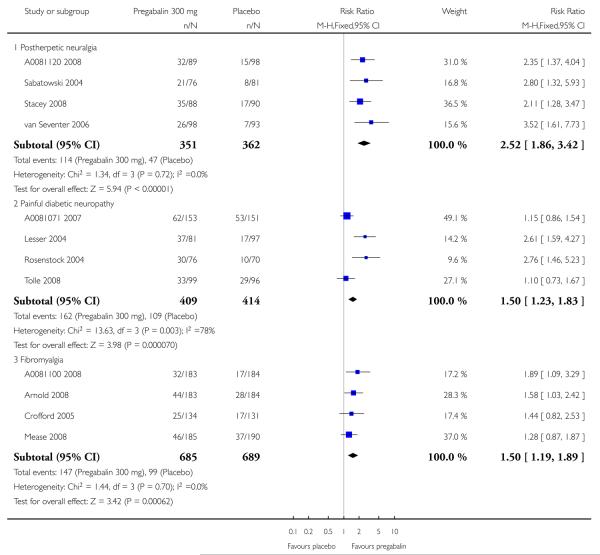

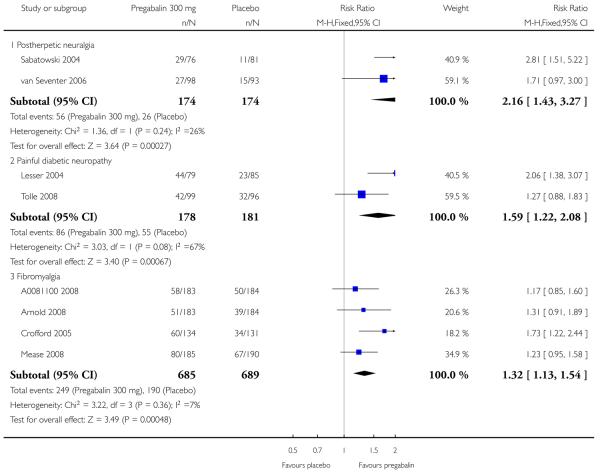

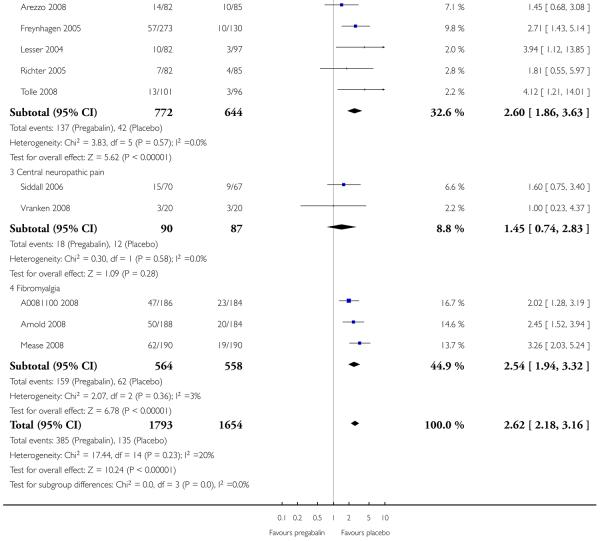

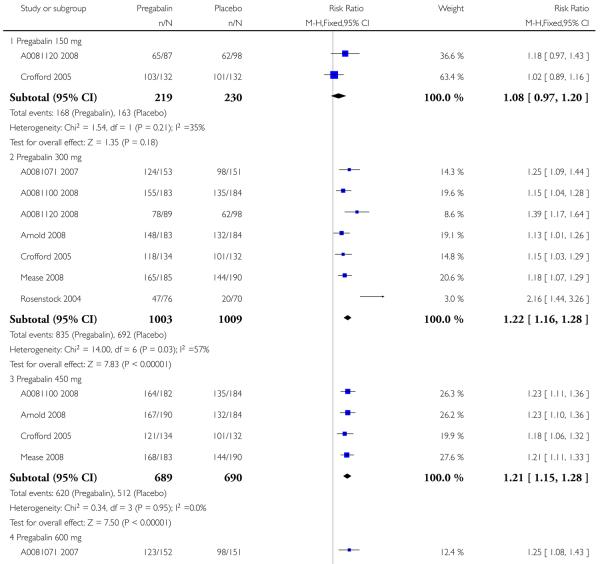

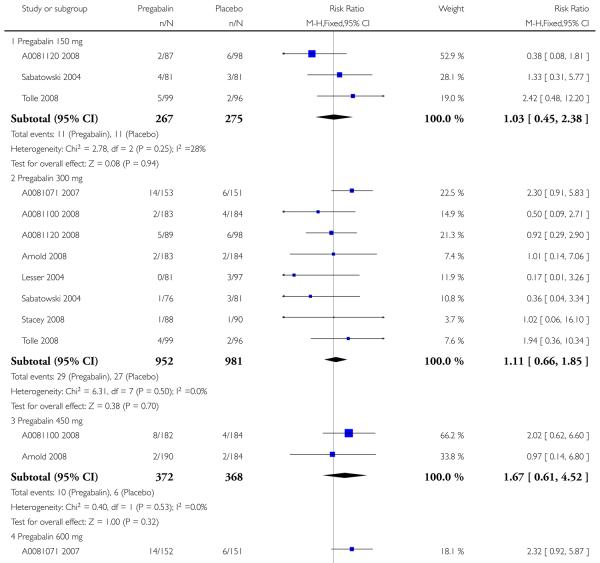

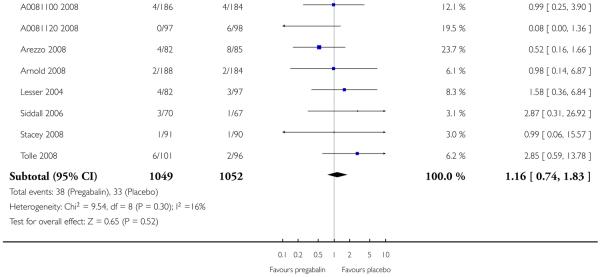

The analysis conducted has concentrated on each condition separately, on efficacy or adverse event outcomes, and by dose (150 mg, 300 mg, 450 mg, and 600 mg daily). The format of results is to examine efficacy and adverse events separately, by condition. Analyses at the end of the document show the same data by dose, outcome, and condition, with analyses 1 to 4 containing data on pregabalin 150 mg, 300 mg, 450 mg, and 600 mg daily.

The five efficacy outcomes consistently reported were participants with:

at least 30% pain relief over baseline;

at least 50% pain relief over baseline;

much or very much improved on patient global impression of change (PGIC);

very much improved on PGIC;

lack of efficacy discontinuation.

Adverse event outcomes were participants with:

at least one adverse event;

at least one serious adverse event;

somnolence;

dizziness;

adverse event discontinuation.

Adverse event reporting was typically not comprehensive, with only those events occurring in 3% to 5% of participants reported. Common adverse events consistently reported were somnolence and dizziness.

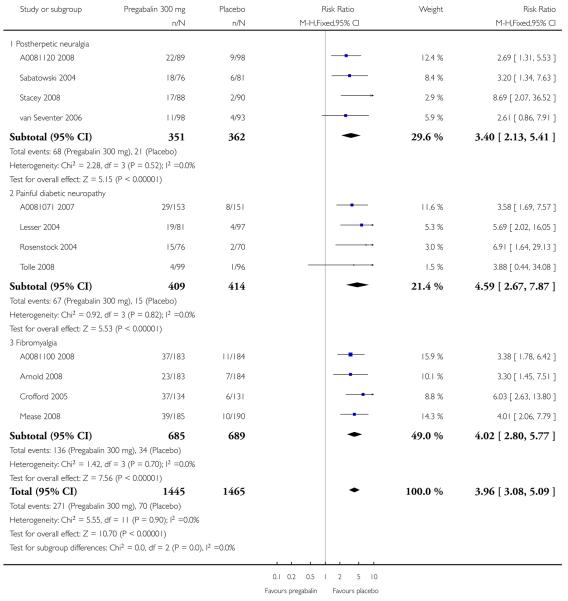

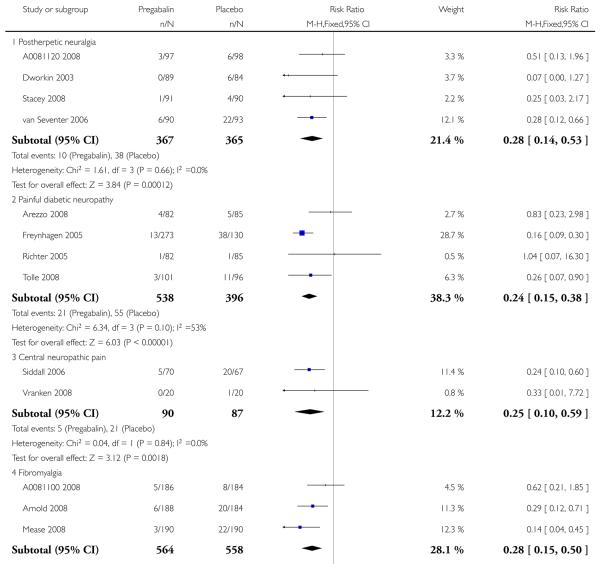

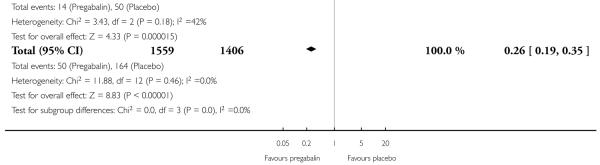

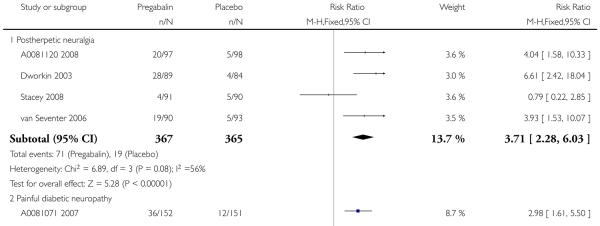

1. Postherpetic neuralgia efficacy

Summary of results A shows results for the four main efficacy outcomes for which data were available. In each case there was a greater response with higher dose, with more participants achieving the outcomes, and with lower (better) NNT values. For lack of efficacy discontinuations there were increasingly fewer discontinuations with higher doses, but with a number needed to treat to prevent (NNTp) one discontinuation about the same for 300 mg and 600 mg daily. At least 30% pain relief (moderate benefit) tended to produce higher response rates and lower NNT values than did at least 50% pain relief (substantial benefit). No studies reported a measure of substantial benefit (very much improved) on the PGIC scale.

Limiting analyses to studies of 8 weeks duration or more made no appreciable difference to the results.

Summary of results A: Efficacy outcomes with different doses of pregabalin in postherpetic neuralgia

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome - daily dose | Studies | Participants | Pregabalin | Placebo | Relative benefit (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

| At least 30% pain relief | ||||||

| 150 mg | 1 | 180 | 39 | 17 | 2.3 (1.4 to 3.8) | 4.6 (2.9 to 11) |

| 300 mg | 2 | 369 | 49 | 24 | 2.1 (1.5 to 2.7) | 4.0 (2.9 to 6.5) |

| 300 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 1 | 191 | 41 | 17 | 2.4 (1.4 to 3.9) | 4.2 (2.8 to 8.9) |

| 600 mg | 3 | 537 | 62 | 24 | 2.5 (2.0 to 3.2) | 2.7 (2.2 to 3.4) |

| 600 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 2 | 356 | 58 | 21 | 2.8 (2.0 to 3.8) | 2.7 (2.2 to 3.7) |

| At least 50% pain relief | ||||||

| 150 mg | 3 | 527 | 25 | 11 | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.4 | 6.9 (4.8 to 13) |

| 300 mg | 4 | 713 | 32 | 13 | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.4) | 5.1 (3.9 to 7.4) |

| 300 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 3 | 535 | 30 | 11 | 2.7 (1.9 to 4.0) | 5.3 (3.9 to 8.1) |

| 600 mg | 4 | 732 | 41 | 15 | 2.7 (2.1 to 3.5) | 3.9 (3.1 to 5.1) |

| 600 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 3 | 551 | 39 | 14 | 2.8 (2.0 to 3.9) | 4.0 (3.1 to 5.5) |

| PGIC much or very much improved | ||||||

| 150 mg | 2 | 342 | 27 | 15 | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.8) | 8.4 (4.9 to 30) |

| 300 mg | 2 | 348 | 32 | 15 | 2.2 (1.4 to 3.3) | 5.8 (3.9 to 12) |

| 600 mg | 1 | 183 | 37 | 16 | 2.3 (1.3 to 3.9) | 4.9 (3.0 to 12) |

| Lack of efficacy discontinuation | NNTp (95% CI) | |||||

| 150 mg | 3 | 527 | 8 | 13 | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.0) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 713 | 4 | 11 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.7) | 15 (9 to 34) |

| 300 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 3 | 535 | 6 | 13 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.7) | 13 (7.9 to 35) |

| 600 mg | 4 | 732 | 3 | 11 | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.5) | 13 (9 to 24) |

| 600 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 3 | 551 | 3 | 13 | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.6) | 11 (7.4 to 22) |

2. Painful diabetic neuropathy efficacy

Summary of results B shows results for the four main efficacy outcomes for which data were available. In each case there was a greater response with a higher dose, with more participants having the outcomes, and with lower (better) NNT values. For lack of efficacy discontinuations there were no fewer discontinuations with higher doses, but with a measurable NNTp because of a higher discontinuation rate with placebo. At least 30% pain relief (moderate benefit) tended to produce higher response rates and lower NNT values than did at least 50% pain relief (substantial benefit). No trials reported a measure of substantial benefit (very much improved) on the PGIC scale.

Limiting analyses to studies of 8 weeks duration or more made no appreciable difference to results.

Summary of results B: Efficacy outcomes with different doses of pregabalin in painful diabetic neuropathy

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome - daily dose | Studies | Participants | Pregabalin | Placebo | Relative benefit (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

| At least 30% pain relief | ||||||

| 150 mg | no data | |||||

| 300 mg | 2 | 482 | 59 | 45 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) | 6.8 (4.3 to 17) |

| 300 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 1 | 304 | 58 | 52 | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | not calculated |

| 600 mg | 3 | 819 | 63 | 43 | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 5.1 (3.8 to 7.8) |

| 600 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 2 | 641 | 62 | 48 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 6.8 (4.4 to 15) |

| At least 50% pain relief | ||||||

| 150 mg | 2 | 359 | 27 | 23 | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.6) | not calculated |

| 150 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 1 | 195 | 34 | 30 | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.7) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 823 | 40 | 26 | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.8) | 7.5 (5.1 to 14) |

| 300 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 3 | 645 | 38 | 29 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) | 11 (6.1 to 54) |

| 600 mg | 6 | 1360 | 45 | 25 | 1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) | 5.0 (4.0 to 6.6) |

| 600 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 4 | 1005 | 46 | 30 | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.8) | 6.3 (4.6 to 10) |

| PGIC much or very much improved | ||||||

| 150 mg | 1 | 195 | 45 | 34 | 1.4 (0.96 to 2.0) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 2 | 359 | 48 | 30 | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) | 5.6 (3.6 to 13) |

| 300 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 1 | 195 | 42 | 33 | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.8) | not calculated |

| 600 mg | 4 | 875 | 56 | 33 | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1) | 4.2 (3.3 to 5.8) |

| 600 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 3 | 702 | 54 | 36 | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.8) | 5.4 (3.9 to 9.2) |

| Lack of efficacy discontinuation | NNTp (95% CI) | |||||

| 150 mg | 2 | 359 | 4 | 7 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.5) | not calculated |

| 150 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 1 | 195 | 8 | 11 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.7) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 2 | 341 | 3 | 8 | 0.4 (0.2 to 1.0) | not calculated |

| 600 mg | 4 | 869 | 4 | 11 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.5) | 14 (9 to 31) |

| 600 mg (≥ 8 weeks) | 3 | 702 | 4 | 14 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.5) | 10 (6.9 to 20) |

3. Central neuropathic pain efficacy

There was relatively little data from two studies on central neuropathic pain, where only 600 mg daily was used. The results are in Summary of results C. Using substantial benefit produced lower response rates, and a higher (worse) NNT, than moderate benefit. There were fewer ’lack of efficacy’ discontinuations with pregabalin compared with placebo.

Summary of results C: Efficacy outcomes with different doses of pregabalin in central neuropathic pain

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome - daily dose | Studies | Participants | Pregabalin | Placebo | Relative benefit (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

| At least 30% pain relief | ||||||

| 600 mg | 1 | 136 | 42 | 13 | 3.1 (1.6 to 6.1) | 3.5 (2.3 to 7.0) |

| At least 50% pain relief | ||||||

| 600 mg | 2 | 176 | 25 | 7 | 3.6 (1.5 to 8.4) | 5.6 (3.5 to 14) |

| Lack of efficacy discontinuation | NNTp (95% CI) | |||||

| 600 mg | 2 | 177 | 6 | 24 | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.6) | 5.4 (3.5 to 12) |

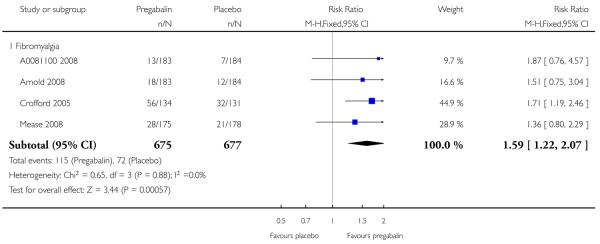

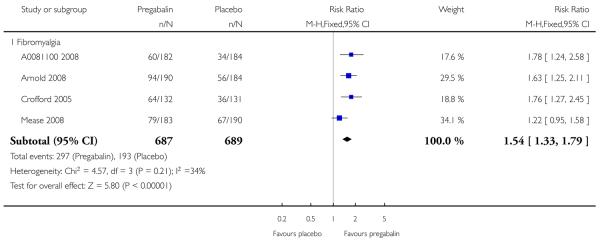

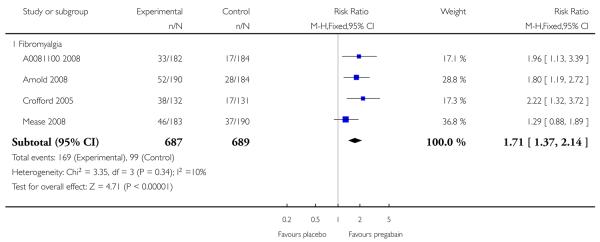

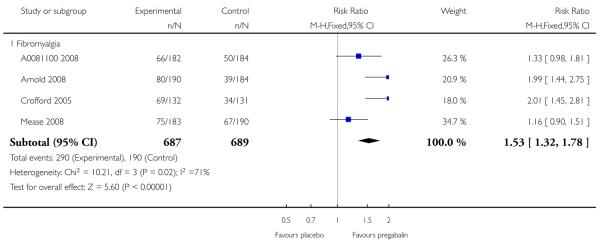

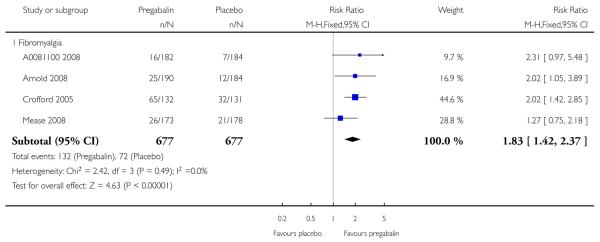

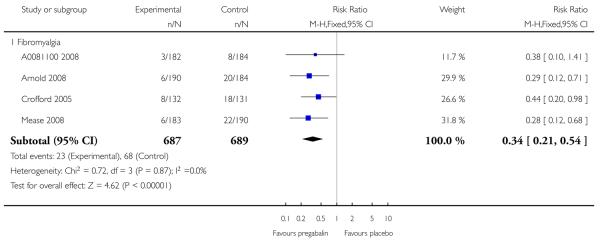

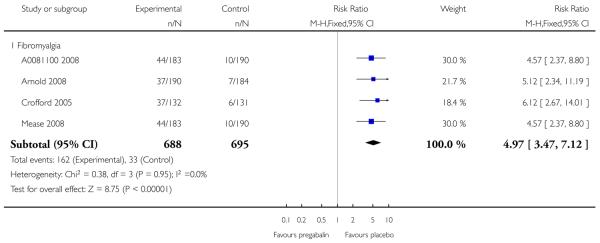

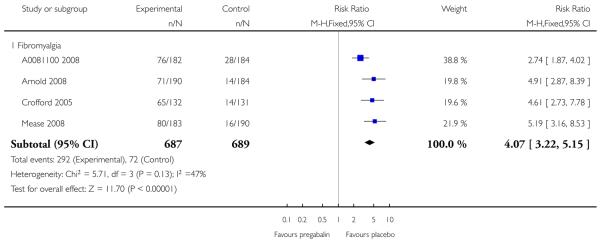

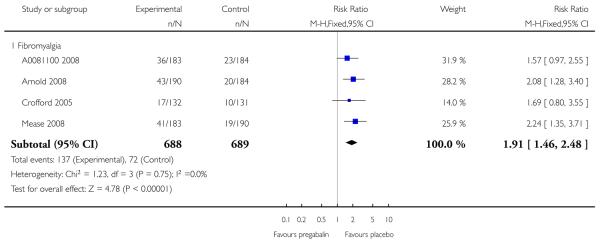

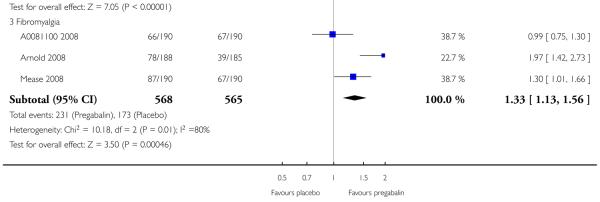

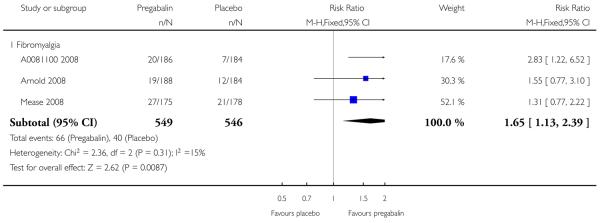

4. Fibromyalgia efficacy

The four classic trials of pregabalin in fibromyalgia (not including that using EERW (Crofford 2008)) provided the most consistent information in terms of efficacy results and dose range.

Summary of results D shows results for the five main efficacy outcomes. In each case there tended to be a greater response with a higher dose of up to 450 mg, with more participants achieving the outcomes, and with lower (better) NNT values; 600 mg seemed to produce no better results than 450 mg for any outcome. For lack of efficacy discontinuations there were fewer discontinuations with higher doses. A daily dose of 150 mg pregabalin was not significantly different from placebo on any measure.

Both measures of moderate benefit produced higher rates of response with pregabalin, and lower (better) values for NNT than measures of substantial benefit, but with overlap of confidence intervals.

The EERW trial (Crofford 2008) used a six-week open titration to allow participants to obtain a substantial benefit (at least 50% pain relief and much or very much improved on PGIC) and have tolerable adverse events. Participants who achieved this outcome then entered a randomised, double blind, 26-week withdrawal phase in which either the established dose or placebo was used. The outcome was loss of therapeutic response, defined as having less than 30% reduction in pain from baseline or worsening, as judged by the investigator, of fibromyalgia symptoms such that alternative treatment was necessary.

During the open label phase, 54% had at least 50% pain relief on a visual analogue scale (VAS) over baseline and a PGIC of much or very much improved and so were able to enter the randomised double-blind phase. During the double blind treatment phase time to loss of therapeutic response was significantly longer for participants receiving pregabalin than for the placebo group. For pregabalin, 90/279 (32%) experienced loss of therapeutic response over 26 weeks, compared with 174/287 (61%) with placebo. The NNT to prevent one patient experiencing a loss of treatment response for fibromyalgia was 3.5 (95% CI 2.8 to 4.9).

Summary of results D: Efficacy outcomes with different doses of pregabalin in fibromyalgia (classic trial design only)

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome - daily dose | Studies | Participants | Pregabalin | Placebo | Relative benefit (95% CI) | NNT (95% CI) |

| At least 30% pain relief | ||||||

| 150 mg | 1 | 263 | 31 | 27 | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.7) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 1374 | 39 | 28 | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) | 9.2 (6.3 to 17) |

| 450 mg | 4 | 1376 | 43 | 28 | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.8) | 6.6 (5.0 to 9.8) |

| 600 mg | 3 | 1122 | 39 | 28 | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) | 9.1 (6.1 to 18) |

| At least 50% pain relief | ||||||

| 150 mg | 1 | 263 | 13 | 13 | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.9) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 1374 | 21 | 14 | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) | 14 (9.0 to 33) |

| 450 mg | 4 | 1376 | 25 | 14 | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.1) | 9.8 (7.0 to 16) |

| 600 mg | 3 | 1122 | 24 | 15 | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.1) | 11 (7.1 to 21) |

| PGIC much or very much improved | ||||||

| 150 mg | 1 | 263 | 32 | 27 | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 1374 | 36 | 28 | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9) | 11 (7.3 to 26) |

| 450 mg | 4 | 1376 | 42 | 28 | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.8) | 6.8 (5.1 to 10) |

| 600 mg | 3 | 1122 | 41 | 28 | 1.5 (1.2 to 1.7) | 7.7 (5.4 to 13) |

| PGIC very much improved | ||||||

| 150 mg | no data | |||||

| 300 mg | 4 | 1352 | 17 | 11 | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.9) | 16 (9.9 to 37) |

| 450 mg | 4 | 1354 | 19 | 11 | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.4) | 11 (7.9 to 20) |

| 600 mg | 3 | 1095 | 12 | 7 | 1.7 (1.1 to 2.4) | 21 (12 to 83) |

| Lack of efficacy discontinuation | NNTp (95% CI) | |||||

| 150 mg | 1 | 263 | 9 | 14 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.3) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 1374 | 4 | 10 | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.7) | 18 (12 to 34) |

| 450 mg | 4 | 1376 | 3 | 10 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.5) | 15 (11 to 25) |

| 600 mg | 3 | 1122 | 2 | 9 | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.5) | 15 (11 to 26) |

5. Participants experiencing at least one adverse event or serious adverse event

Results for participants experiencing at least one adverse event or serious adverse event were not reported in all studies. Consequently, the analysis in Summary of results E is by dose only, and not by dose and condition. Most participants with pregabalin and placebo reported at least one adverse event over the period, with no indication of a dose-response relationship. A small proportion reported at least one adverse event considered serious (almost certainly using pre-set criteria of seriousness). There was no difference in the incidence of adverse events between pregabalin and placebo, and no indication of any dose response.

Summary of results E: Participants experiencing at least one adverse event or serious adverse event

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome - daily dose | Studies | Participants | Pregabalin | Placebo | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) |

| At least one adverse event | ||||||

| 150 mg | 2 | 449 | 77 | 71 | 1.2 (0.97 to 1.4) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 8 | 2190 | 82 | 67 | 1.2 (1.17 to 1.29) | 6.6 (5.4 to 8.7) |

| 450 mg | 4 | 1379 | 90 | 74 | 1.2 (1.15 to 1.27) | 6.3 (5.1 to 8.5) |

| 600 mg | 9 | 2540 | 83 | 67 | 1.3 (1.25 to 1.37) | 6.1 (5.1 to 7.7) |

| At least one serious adverse event | ||||||

| 150 mg | 3 | 542 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.3) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 8 | 1566 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.1) | not calculated |

| 450 mg | 2 | 740 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 (0.6 to 4.5) | not calculated |

| 600 mg | 9 | 2101 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 1.2 (0.7 to 1.8) | not calculated |

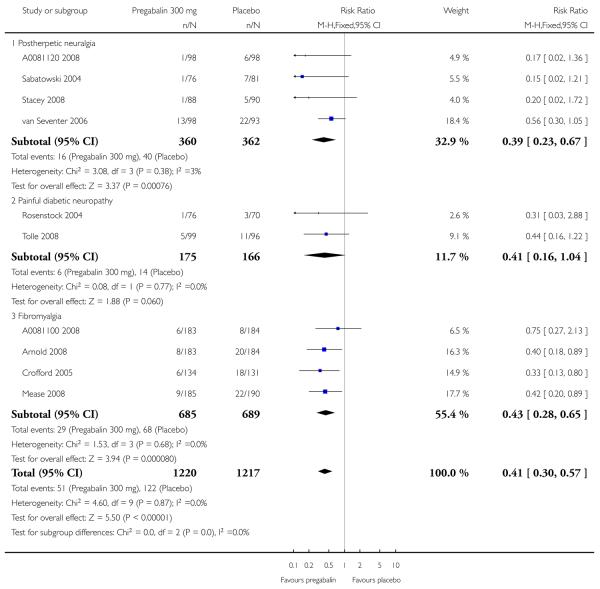

6. Adverse events in postherpetic neuralgia

Results for somnolence, dizziness and adverse event discontinuation are shown in Summary of results F. Higher doses produced higher adverse event rates with pregabalin, and lower (worse) NNH values. Between one participant in 10 and one in five discontinued because of an adverse event. Only for somnolence did 150 mg produce higher adverse event rates than placebo.

Summary of results F: Somnolence, dizziness, and adverse event discontinuation in postherpetic neuralgia

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome - daily dose | Studies | Participants | Pregabalin | Placebo | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) |

| Somnolence | ||||||

| 150 mg | 3 | 527 | 15 | 7 | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.7) | 12 (7.3 to 34) |

| 300 mg | 4 | 713 | 19 | 6 | 3.0 (2.1 to 5.3) | 7.4 (5.5 to 11) |

| 600 mg | 4 | 732 | 25 | 6 | 4.4 (2.8 to 6.8) | 5.2 (4.1 to 7.0) |

| Dizziness | ||||||

| 150 mg | 3 | 527 | 13 | 10 | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.1) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 713 | 30 | 9 | 3.2 (2.3 to 4.6) | 4.7 (3.7 to 6.5) |

| 600 mg | 4 | 732 | 35 | 9 | 4.0 (2.8 to 5.7) | 3.8 (3.2 to 4.9) |

| Adverse event discontinuation | ||||||

| 150 mg | 3 | 527 | 9 | 7 | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.3) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 713 | 17 | 6 | 2.7 (1.7 to 4.3) | 9.3 (6.5 to 16) |

| 600 mg | 4 | 732 | 19 | 5 | 3.7 (2.3 to 6.0) | 7.1 (5.3 to 11) |

7. Adverse events in painful diabetic neuropathy

Results for somnolence, dizziness and adverse event discontinuation are shown in Summary of results G. Higher doses produced higher adverse event rates with pregabalin, and lower (worse) NNH values. Between one participant in 20 and one in five discontinued because of an adverse event. Pregabalin 150 mg produced adverse event rates no different from placebo.

Summary of results G: Somnolence, dizziness, and adverse event discontinuation in painful diabetic neuropathy

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome - daily dose | Studies | Participants | Pregabalin | Placebo | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) |

| Somnolence | ||||||

| 150 mg | 2 | 359 | 5 | 2 | 2.3 (0.7 to 7.5) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 823 | 16 | 4 | 4.6 (2.7 to 7.9) | 7.8 (6.0 to 11) |

| 600 mg | 6 | 1351 | 15 | 2 | 4.6 (2.9 to 7.3) | 8.8 (7.0 to 12) |

| Dizziness | ||||||

| 150 mg | 2 | 359 | 6 | 2 | 2.8 (0.9 to 8.7) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 823 | 23 | 5 | 4.7 (3.0 to 7.5) | 5.5 (4.4 to 7.4) |

| 600 mg | 3 | 1122 | 46 | 10 | 4.4 (3.4 to 5.8) | 2.8 (2.5 to 3.2) |

| Adverse event discontinuation | ||||||

| 150 mg | 2 | 359 | 4 | 4 | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.9) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 823 | 11 | 5 | 2.3 (1.4 to 3.8) | 16 (9.9 to 37) |

| 600 mg | 6 | 1351 | 18 | 6 | 2.6 (1.8 to 3.7) | 8.8 (6.8 to 12) |

8. Adverse events in central neuropathic pain

Results for somnolence, dizziness and adverse event discontinuation are shown in Summary of results H. Pregabalin 600 mg produced significantly more somnolence and dizziness, but no higher rate of adverse event discontinuation.

Summary of results H: Somnolence, dizziness, and adverse event discontinuation in central neuropathic pain

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome - daily dose | Studies | Participants | Pregabalin | Placebo | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) |

| Somnolence | ||||||

| 600 mg | 2 | 177 | 42 | 17 | 2.5 (1.5 to 4.1) | 4.0 (2.6 to 8.3) |

| Dizziness | ||||||

| 600 mg | 2 | 177 | 27 | 14 | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.6) | 7.8 (4.1 to 82) |

| Adverse event discontinuation | ||||||

| 600 mg | 2 | 177 | 20 | 14 | 1.5 (0.7 to 2.8) | not calculated |

9. Adverse events in fibromyalgia

Results for somnolence, dizziness and adverse event discontinuation are shown in Summary of results H. Higher doses produced higher adverse event rates with pregabalin, and lower (worse) NNH values. Between one participant in 10 and one in three discontinued because of an adverse event. Only for somnolence did 150 mg produce higher adverse event rates than placebo.

In the EERW study (Crofford 2008) 863 of 1051 participants (82%) entering the open label phase experienced at least one adverse event. The most common adverse events during this phase were dizziness and somnolence. One hundred and ninety-six participants (19%) withdrew during the open label phase because of adverse events. Of the participants entering the double blind phase, 129/287 (45%) of participants in the placebo group, 37/63 (59%) of participants taking 300 mg, 46/73 (63%) taking 450 mg, and 89/143 (62%) participants taking 600 mg pregabalin experienced an adverse event. During the open label phase, serious adverse events occurred in 8/1051 participants (0.8%).

Summary of results H: Somnolence, dizziness, and adverse event discontinuation in fibromyalgia

| Number of | Percent with outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome - daily dose | Studies | Participants | Pregabalin | Placebo | Relative risk (95% CI) | NNH (95% CI) |

| Somnolence | ||||||

| 150 mg | 1 | 263 | 16 | 5 | 3.5 (1.5 to 8.3) | 8.8 (5.4 to 24) |

| 300 mg | 4 | 1374 | 20 | 5 | 4.0 (2.8 to 5.8) | 6.7 (5.5 to 8.7) |

| 450 mg | 4 | 1376 | 21 | 5 | 4.2 (2.9 to 6.0) | 6.4 (5.2 to 8.1) |

| 600 mg | 3 | 1122 | 23 | 5 | 4.5 (3.1 to 6.7) | 5.7 (4.6 to 7.3) |

| Dizziness | ||||||

| 150 mg | 3 | 527 | 13 | 10 | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.1) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 1374 | 32 | 10 | 3.1 (2.4 to 3.9) | 4.6 (3.9 to 5.7) |

| 450 mg | 4 | 1376 | 43 | 10 | 4.1 (3.2 to 5.2) | 3.1 (2.8 to 3.6) |

| 600 mg | 3 | 1122 | 46 | 10 | 4.4 (3.4 to 5.8) | 2.8 (2.5 to 3.2) |

| Adverse event discontinuation | ||||||

| 150 mg | 1 | 263 | 8 | 8 | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.5) | not calculated |

| 300 mg | 4 | 1374 | 16 | 10 | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) | 17 (11 to 43) |

| 450 mg | 4 | 1377 | 20 | 10 | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.5) | 11 (7.6 to 18) |

| 600 mg | 3 | 1122 | 28 | 11 | 2.5 (1.9 to 3.3) | 5.9 (4.6 to 8.0) |

For details of risk of bias see Figure 2.

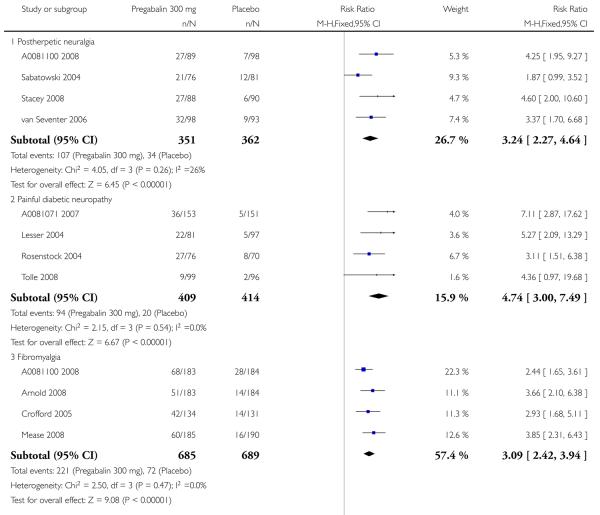

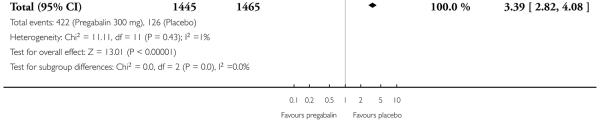

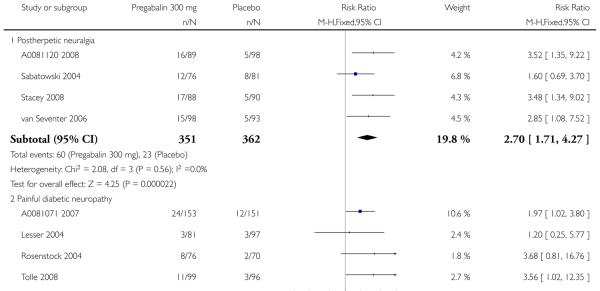

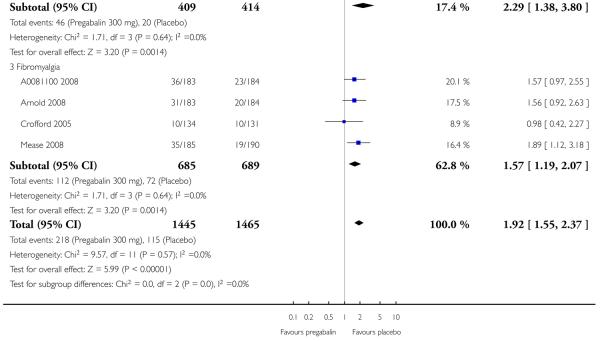

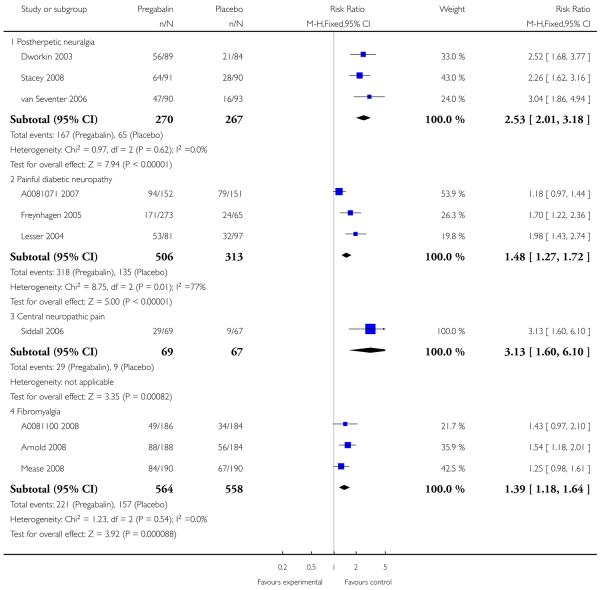

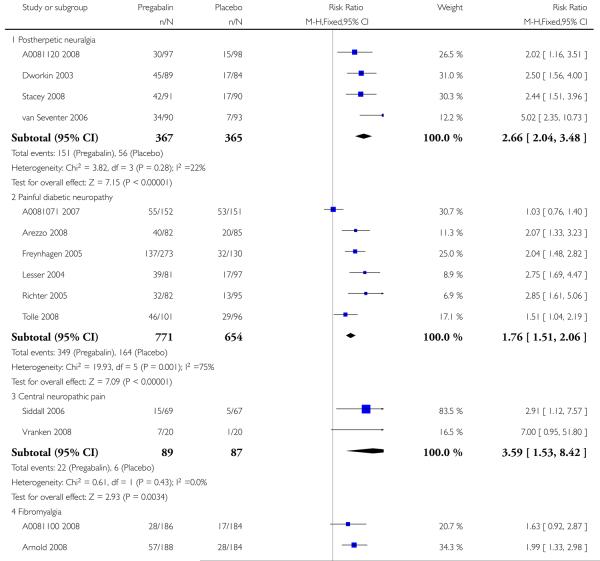

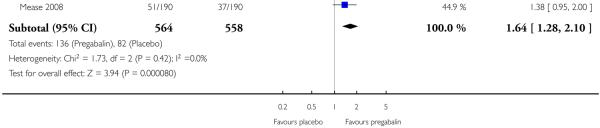

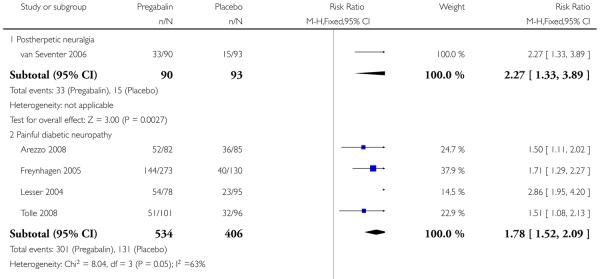

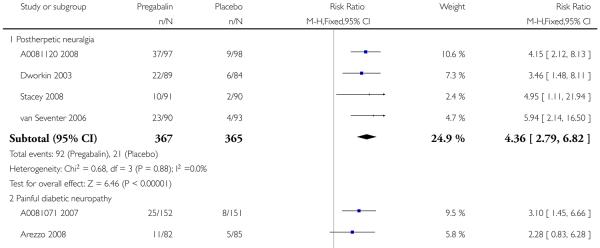

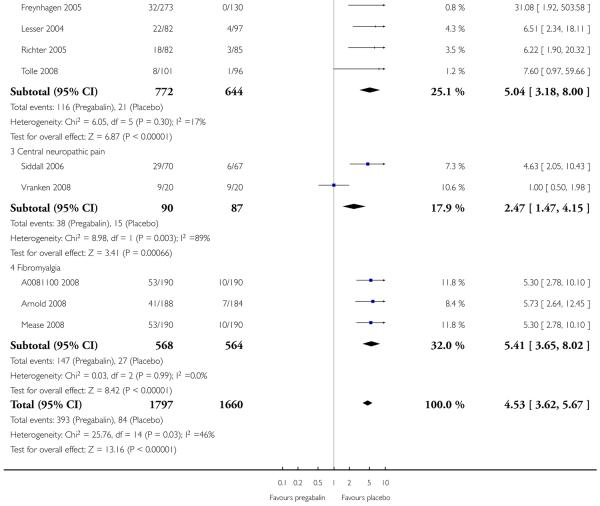

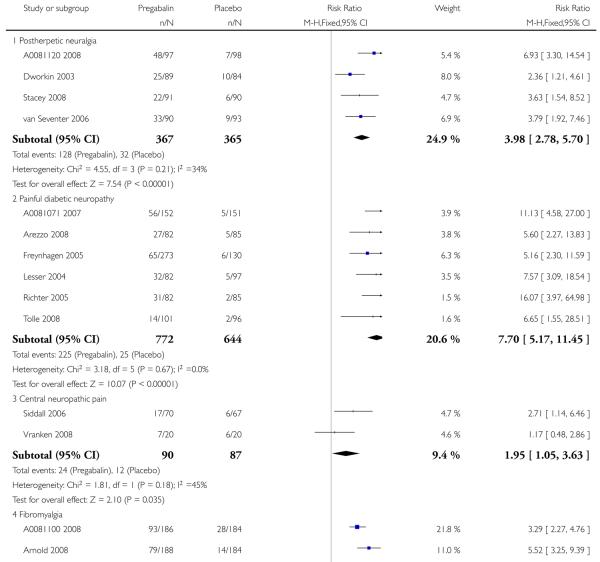

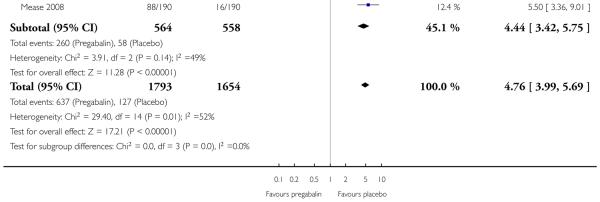

For efficacy see Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4; Analysis 1.5; Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4; Analysis 2.5; Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4; Analysis 3.5; Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2; Analysis 4.3; Analysis 4.4; Analysis 4.5.

For adverse events see Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8; Analysis 2.6; Analysis 2.7; Analysis 2.8; Analysis 3.6; Analysis 3.7; Analysis 3.8; Analysis 4.6; Analysis 4.7; Analysis 4.8; Analysis 5.1; Analysis 6.1.

DISCUSSION

Conventional assessment of the analgesic effect of drugs involves measuring pain intensity reduction or pain relief in participants with established moderate or severe pain, in order for studies to be sensitive. The assessment of perioperative use of combination therapies to reduce postoperative pain is more difficult because participants often have low levels of pain. There are a number of complexities, and no definitive method that clearly delivers a correct answer, as a methodological review of perioperative gabapentin studies showed (McQuay 2008b). This review has no clear message about pregabalin in acute painful conditions because there was only a single study of proven classic design in postoperative pain.

By contrast, the review has examined what is arguably the largest data set of high quality, longer-duration studies in four chronic painful conditions with neuropathic involvement. Anti-epileptic drugs have been used before for chronic pain with neuropathic involvement, and for prophylaxis of migraine (McQuay 1995; Wiffen 2005a; Wiffen 2005b; Wiffen 2005c). Information on the analgesic effects of antiepileptics in acute and chronic nociceptive conditions is very limited, but these drugs are not generally effective in acute painful conditions like postoperative pain or chronic nociceptive conditions like arthritis (Wiffen 2005c).

Summary of main results

There is no clear evidence of any beneficial effects of pregabalin in acute postoperative pain. No studies were found of pregabalin in chronic nociceptive pain conditions like arthritis.

Pregabalin at doses of 300 mg, 450 mg, and 600 mg daily produced useful benefits in patients with PHN, PDN, CNP and fibromyalgia. Pregabalin at 150 mg daily was generally ineffective except in PHN. This was the case for several dichotomous outcomes equating to moderate or substantial pain relief as defined by the IMMPACT group (Dworkin 2008), alongside lower rates of lack of efficacy discontinuations with increasing dose.

With increasing daily dose also came increasing rates of adverse events like somnolence and dizziness, as well as more discontinuations because of adverse events. The proportion of participants reporting at least one adverse event was not affected by dose, nor was the number of participants with a serious adverse event, which was not more than with placebo.

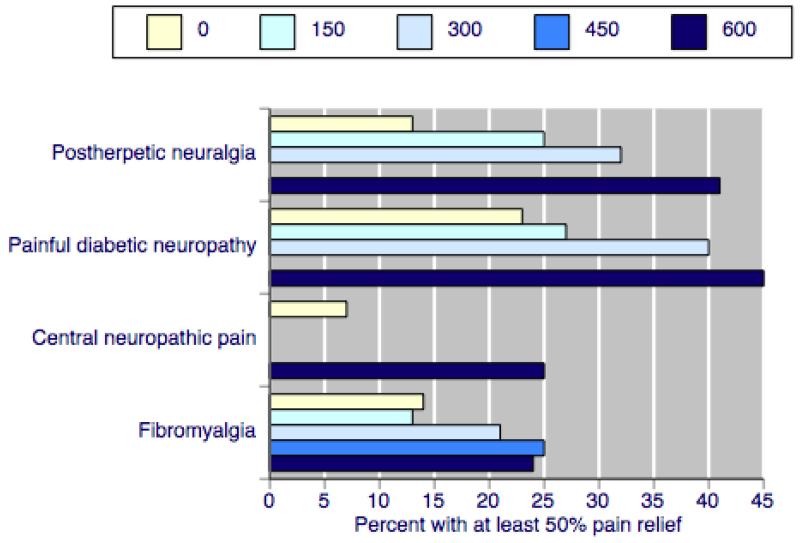

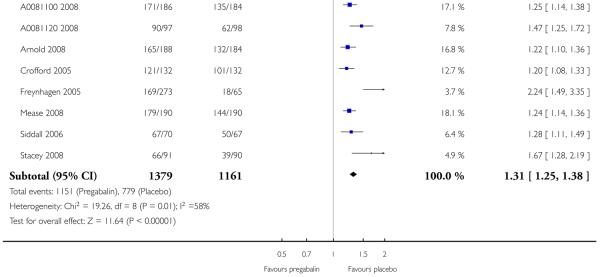

There were obvious differences in pregabalin efficacy between the four painful conditions, as measured by response rate and NNT. For example, Figure 3 shows the rates of substantial benefit with pregabalin 150 mg to 600 mg for the four conditions using the outcome of at least 50% pain relief over baseline. Much higher rates were found with PHN and PDN than with CNP and fibromyalgia. NNTs for the former for moderate and substantial benefit on any outcome were generally six and below for 300 mg and 600 mg daily; for fibromyalgia NNTs were much higher, and generally seven and above. CNP, with an NNT of 5.6 for 600 mg daily, had a low response rate and low placebo response. The low number of participants (177) limits how far this interpretation can be taken.

Figure 3. Percentage of participants with at least 50% pain relief with placebo or four daily pregabalin doses at trial end in four painful conditions.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

It is likely that all of the completed clinical trials have been found, because summaries of completed but unpublished trials are now available on the Internet, though not necessarily easy to find. In this review we had information from six studies (649 participants) for acute perioperative use. This is not a large amount for acute pain, and only one of the studies (Hill 2001) was a classic study design in established postoperative pain designed to show analgesic efficacy.

For four conditions in chronic pain with neuropathic involvement there were 19 studies with 7003 participants. This is a large amount of information, both in terms of studies and numbers of participants. Studies were all of four weeks duration or longer, and most were of 8 to 14 weeks. This very large amount of information can be compared to fewer than 600 participants for individual antidepressants in neuropathic pain, (Sultan 2008), with 404 participants for carbamazepine (Wiffen 2005b), and 1468 for gabapentin for acute and chronic pain combined (Wiffen 2005c).

There remained the problem of consistent reporting of outcomes, especially dichotomous outcomes of efficacy. The number of participants with at least 30% pain relief, and the number with PGIC very much improved were frequently not reported. For adverse events the number with at least one adverse event, and at least one serious adverse event was not reported in all studies. Reporting of particular adverse events was typically curtailed, so that only adverse events affecting 5% or so of participants was reported. To adequately access this information, data from clinical trial reports is usually needed (Edwards 2004; Moore 2005). The problem of reporting of adverse events has been commented on before (Edwards 1999; Ioannidis 2001; Loke 2001).

Quality of the evidence

All the studies in the review were described as randomised and double blind, and scored at least three out of five points on a validated scale (Jadad 1996). Chronic pain studies were predominantly of six weeks duration or longer and generally reported clinically useful outcomes, making them valid. Studies also tended to be large, with reasonable group sizes, making the random play of chance less of a problem, and the total numbers of participants and events was larger than needed to minimise chance effects (Moore 1998). Diagnostic criteria for inclusion were reasonable using appropriate definitions and duration of pain, and participants in chronic pain studies all had to have pain of 40% of maximum, indicating that they had pain of at least moderate intensity. This means that studies would be sensitive enough to measure any analgesic effect.

Potential biases in the review process

Study quality was such as to minimise any bias. There was nothing obvious in study design that might lead to bias, and the one aspect that has been questioned, that of partial enrichment in some studies, has been shown already not to have had any measurable effect (Straube 2008). One study had complete enriched enrolment, but its results are reviewed separately and not combined with other studies in any analyses. In any event, the results from this enriched EERW study in fibromyalgia (Crofford 2008) were not strikingly different from those of a classic study design.

In the four trials in fibromyalgia of classical study design, about 40% of participants taking pregabalin 300 to 600 mg daily had a PGIC rating of much or very much improvement over 8 to 14 weeks. In the EERW study, 54% of those participants who entered the open label phase had at least 50% pain relief on a VAS over baseline and a PGIC of much or very much improved after six weeks and so continued into the double-blind phase. Comparing these two response rates, the larger size of effect observed in the EERW study was obtained during an open label phase, without a placebo group, and in participants titrated to an optimal dose of pregabalin rather than a fixed dose. The smaller effect size (about 40%) occurred in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, in which participants were largely randomised to different doses of pregabalin irrespective of which dose might suit them best. Given these differences in trial design, the difference in response rates was not surprising.

Not all outcomes were available for all studies. It is possible that results could change if all outcomes were available for all studies. It is possible that trial duration may have an effect on efficacy, with studies shorter than eight weeks over-estimating efficacy compared with studies of eight weeks or longer (Moore 2009). Study duration was four weeks in one study in PHN (Stacey 2008), and five weeks (Lesser 2004), and six weeks (Richter 2005) in two in PDN. The largest contribution of studies of less than eight weeks duration was for at least 50% pain relief in PDN. Omission of these two studies would have made the calculated NNT 6.3 (4.6 to 10) rather than 5.0 (4.0 to 6.6); though larger, the difference was not significant. Eighteen of the 19 chronic pain studies were sponsored by Pfizer or Parke-Davis; the single study not mentioning sponsorship had only 40 participants (Vranken 2008). All were published since 2004. Three extensive abstracts, containing details of the design and results of unpublished trials, with about 1600 participants were identified in the PhRMA clinical study results database, so that almost a quarter of participant data came from studies unpublished in February 2009. It not likely that there is a substantial additional body of completed but unpublished studies in neuropathic pain. For example, it would require about three times as many participants in trials with zero treatment effect to increase the NNT of 600 mg to above 12 in studies of PHN or PDN (Moore 2008).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Several previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses mention pregabalin.

A systematic review of gabapentin and similar drugs in perioperative pain (Dahl 2004) found only the study of Hill 2001, though it and a second, similar, review (Tiippana 2007) were generally favourable to the use of gabapentin or pregabalin in the perioperative period. We find the evidence for pregabalin use during the perioperative period less than compelling. Only one of six studies had a positive outcome in favour of pregabalin, while five were negative. It may be that the previous reviews have incorrectly assumed that gabapentin and pregabalin have the same effects in acute pain.

Based on two studies, a systematic review of treatment for PHN concluded that pregabalin was effective, using several different efficacy outcomes (Hempenstall 2005). Evidence-based guidelines, backed by systematic searching and analysis, concluded that pregabalin provided level A evidence for use in neuropathic pain (Attal 2006), and a second set of consensus guidelines based on systematic reviews indicated that pregabalin should be considered as first line treatment for neuropathic pain (Moulin 2007). A systematic review that combined different neuropathic pain conditions and fibromyalgia, but with only about 2400 participants in all, came to broadly similar conclusions about dichotomous efficacy and adverse events as this review (Straube 2008), though NNTs were understandably numerically different. A review of central nervous system adverse events of new antiepileptic drugs with 938 participants in four studies not involved with pain identified dizziness and somnolence as major adverse events, with some differences in ataxia and fatigue (Zaccara 2008).

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Pregabalin at daily oral doses of 300 to 600 mg provides high levels of benefit for a minority of patients experiencing neuropathic pain (painful diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, central neuropathic pain) and fibromyalgia, conditions that are difficult to treat and carry a substantial health burden. The quality of the evidence is good, from studies at low risk of bias, of long duration, with clinically useful outcomes, and with large numbers of participants. An important finding is that some patients will not have a useful benefit with pregabalin, and for those individuals another therapeutic intervention should be tried. There is no evidence to support the use of pregabalin in acute pain scenarios.

Implications for research

While the quality and weight of evidence supporting pregabalin in these conditions probably surpasses that available for other interventions, it has largely been generated for regulatory purposes. We need more information about which patients are likely to benefit most with this drug, how best to titrate dose to effect to minimise adverse effects, and whether patients who failed on other drugs can still benefit from pregabalin.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Pregabalin for acute and chronic pain in adults

Pregabalin relieves pain caused by damage to nerves, either from injury or disease. Antiepileptics (such as pregabalin) are medicines used for treating epilepsy, but are also effective for treating pain. The type of pain that responds well to pregabalin treatment is neuropathic pain (pain caused by damage to nerves). This includes postherpetic neuralgia (persistent pain in an area previously affected by shingles) and painful complications of diabetes, as well as fibromyalgia. Only a minority of patients with these types of pain will have a substantial benefit, and somewhat more will have moderate benefit. With pregabalin daily doses of 300 mg to 600 mg, the patient global impression of change rating of much or very much improved was about 35% in postherpetic neuralgia, 50% in painful diabetic neuropathy, and 40% in fibromyalgia. There is no evidence that pregabalin is effective in acute conditions where pain is already established, and in chronic conditions in which nerve damage is not the prime source of the pain, such as arthritis.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

Oxford Pain Research Funds, UK.

External sources

NHS Cochrane Collaboration Grant, UK.

NIHR Biomedical Research Centre Programme, UK.

Funding for RAM

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no obvious enriched enrolment. Initial dose titration before fixed dose (13 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Painful diabetic neuropathy for at least 3 months, with average daily pain score of at least 40 mm/100 mm. Mean age 59 years, 57% male, majority white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 300 mg daily, n = 153 Pregabalin 600 mg daily, n = 152 Placebo daily, n = 151 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 30% or ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R1, D2, W1 = 4/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Stated to be randomised |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “matching placebo” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no obvious enriched enrolment. Initial dose titration before fixed dose (14 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Fibromyalgia according to ACR classification and pain of at least 40/100 mm in week before randomisation. Mean age 49 years, 91% female, 76% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 300 mg daily, n = 183 Pregabalin 450 mg daily, n = 182 Pregabalin 600 mg daily, n = 186 Placebo daily, n = 184 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 30% or ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R1, D1, W1 = 3/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Stated to be randomised |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “matching placebo” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no obvious enriched enrolment. Initial dose titration before fixed dose (13 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Pain persisting for at least 3 months after healing of herpes zoster skin rash, with average daily pain score of at least 40 mm/100 mm. Mean age 70 years, 54% male | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 150 mg daily, n = 86 Pregabalin 300 mg daily, n = 89 Pregabalin 600 mg daily, n = 97 Placebo daily, n = 97 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 30% or ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R1, D1, W1 = 3/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Stated to be randomised |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Stated to be double blind |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group. Single oral dose | |

| Participants | Adults undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Mean age 46 years | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 150 mg preoperatively, n = 30 Placebo, n = 30 |

|

| Outcomes | Pain at rest and on activity, and postoperative opioid consumption | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 No sponsorship mentioned |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “computer generated table of random numbers” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Administered by independent nurse |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical placebo” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no enriched enrolment. Initial dose titration before fixed dose (13 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Painful diabetic neuropathy for at least 3 months, with average daily pain score of at least 40 mm/100 mm over seven days. Mean age 58 years, 60% male, 73% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 600 mg daily, n = 82 Placebo daily, n = 85 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 30% or ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “computer generated random code” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Remote administration |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical capsules” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no enriched enrolment. Initial dose titration before fixed dose (14 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Fibromyalgia according to ACR classification and pain of at least 40/100 mm in week before randomisation. Mean age 50 years, 95% female, 91% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 300 mg daily, n = 183 Pregabalin 450 mg daily, n = 190 Pregabalin 600 mg daily, n = 188 Placebo daily, n = 184 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 30% or ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “computer generated random code” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Remote administration |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | “identical in appearance and taste” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, partial enriched enrolment. Initial dose titration before fixed dose for 450 mg only (8 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Fibromyalgia according to ACR classification and pain of at least 40/100 mm in week before randomisation. Mean age 49 years, 92% female, 93% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 150 mg daily, n = 132 Pregabalin 300 mg daily, n = 134 Pregabalin 450 mg daily, n = 132 Placebo daily, n = 131 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 30% or ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D1, W1 = 4/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “computer generated code” |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Stated to be double blind |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, complete enriched enrolment with randomised withdrawal. Participants initially screened for response (≥ 50% decrease in pain and PGIC of much or very much improved). Responders to initial titration selected for randomisation to placebo or continued use of tolerated effective dose | |

| Participants | Fibromyalgia according to ACR classification and pain of at least 40/100 mm in week before randomisation, with six months of follow up. Mean age 49 years, 95% female, 91% white | |

| Interventions | 1051 entered open label phase; 566 randomised to double blind phase Pregabalin titrated to a maximum of 600 mg daily, n = 279 Placebo daily, n = 287 |

|

| Outcomes | Loss of therapeutic response | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Stated to be randomised |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Remote administration |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “matching placebo” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, partial enriched enrolment. Titration of over 1 week (9 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Painful postherpetic neuralgia 3 months after healing of herpes zoster skin rash and pain of at least 40/100 mm or numerical rating of at least 4/11 at baseline. Mean age 71 years, 53% female, 95% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 600 mg daily, n = 89 Placebo daily, n = 84 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 30% or ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Random number generator |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Protocol for concealment |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical in appearance” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no enriched enrolment Fixed and flexible dosing regimens | |

| Participants | Chronic neuropathic pain (diabetic neuropathy, post herpetic neuralgia) of more than 3 months, and pain at least 40/100 mm. Mean age 62 years, 46% female, 98% white | |

| Interventions | Flexible regimen of pregabalin 150, 300, 450, or 600 mg daily daily based on individual response, n = 141 Fixed 300 mg/day for 1 week followed by 600 mg daily (12 weeks in total), n = 132 Placebo, n = 65 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R1, D2, W1 = 4/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Stated to be randomised |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “matching placebo capsules” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group. Single oral dose. | |

| Participants | Oral surgery for removal of one or more third molars. Initial pain mild in 17%, and moderate or severe in others. Mean age 24 years, 59% female, 92% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 50 mg, n = 49 Pregabalin 300 mg, n = 50 Ibuprofen 400 mg, n = 49 Placebo, n = 50 |

|

| Outcomes | Pain intensity difference, time to remedication | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R1, D1, W1 = 3/5 Parke-Davis/Warner-Lambert sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Stated to be randomised |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Stated to be blinded |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group | |

| Participants | Women undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy. Mean age 50 years | |

| Interventions | Diazepam 10 mg, n = 30 pregabalin 150 mg, n = 30 pregabalin 300 mg, n = 30 All given 1 hour preoperatively, and 12 hours later, when placebo was given to those initially given diazepam, and pregabalin 150 mg or 300 mg to those initially given pregabalin 150 mg or 300 mg (24 hr study) |

|

| Outcomes | Postoperative pain using 11-point numerical rating scale | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 HUCH-EVO Committee and Paulo Foundation sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “computer generated random number table” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “opaque containers” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical capsules” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group. Single oral dose | |

| Participants | Laparoscopic gynaecological surgery. Mean age 36 years | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 75 mg, n = 30 Pregabalin 150 mg, n = 30 Diazepam 5 mg, n = 30 all in addition to ibuprofen 800 mg |

|

| Outcomes | Postoperative pain using 11-point numerical rating scale | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 HUCH-EVO Committee and Paulo Foundation sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “computer generated random number table” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “opaque containers” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical capsules” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, partial enriched enrolment. 5-day titration (5 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Painful diabetic neuropathy for 1-5 years, and pain at least 40/100 mm. Mean age 60 years, 40% female, 95% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 75 mg daily, n = 77 Pregabalin 300 mg daily, n = 81 Pregabalin 600 mg daily, n = 82, Placebo daily, n = 97 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “random number table” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Remote administration |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | double dummy technique |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group. Single oral dose | |

| Participants | Adult patients undergoing hip arthroplasty. Mean age 68 years | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 300 mg, n = 42 Pregabalin 300 mg + dexamethasone 8 mg, n = 42 Placebo, n = 42 |

|

| Outcomes | 24-hour postoperative morphine consumption, with pain scores at rest and on activity | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 No pregabalin-related sponsorship mentioned |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “computer generated block randomisation” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “no person was aware of assignment” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical capsules” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, partial enriched enrolment. 1-week titration for 600 mg dose (13 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Fibromyalgia according to ACR classification and pain of at least 40/100 mm in week before randomisation. Mean age 49 years, 94% female, 91% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 300 mg daily, n = 185 Pregabalin 450 mg daily, n = 183 Pregabalin 600 mg daily, n = 190 Placebo daily, n = 190 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R1, D1, W1 = 3/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Stated to be randomised |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Stated to be double blind |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group. Single oral dose | |

| Participants | Minor gynaecological surgery involving cervix and uterus, but without incision (dilation and curettage, hysteroscopy). Mean age 44 years | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 100 mg given orally 1 hour before surgical intervention (24 hour study), n = 45 Placebo, n = 45 |

|

| Outcomes | Pain scores and opioid use over 24 hours | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 Pfizer sponsored | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “computer derived random number sequence” |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | “sealed opaque envelopes” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical capsules” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no enriched enrolment. 2-week titration. (6 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Painful diabetic neuropathy for 1-5 years, and pain at least 40/100 mm. Mean age 57 years, 60% female, 84% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 150 mg daily, n = 79 Pregabalin 600 mg daily, n = 82 Placebo daily, n = 85 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “computer generated” |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | double dummy technique |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, partial enriched enrolment. No titration (8 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Painful diabetic neuropathy for 1-5 years, and pain at least 40/100 mm. Mean age 60 years, 56% female, 88% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 300 mg daily, n = 76 Placebo daily, n = 70 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D1, W1 = 4/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “randomisation schedule” |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Not adequately described |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, partial enriched enrolment. 1-week fixed titration (8 weeks in total) | |

| Participants | Painful postherpetic neuralgia 6 months after healing of herpes zoster skin rash and pain of at least 40/100 mm or numerical rating of at least 4/11 at baseline. Mean age 72 years, 45% female, 99% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 150 mg daily, n = 81 Pregabalin 300 mg daily, n = 76 Placebo daily, n = 81 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 Parke-Davis Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “computer generated code” |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical capsules” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no enriched enrolment | |

| Participants | Spinal cord injury (paraplegia or tetraplegia) at least 1 year previously, non progressive 6 months, with chronic pain at least 3 months at least 40/100 mm. Mean age 50 years, 17% female, 97% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin up to 600 mg daily, with variable titration (12 weeks in total), n = 70 Placebo, n = 67 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 5/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “computer generated” |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical size colour taste and smell” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no enriched enrolment. Double blind phase 4 weeks, with at least two weeks of escalation allowed in flexible dose phase | |

| Participants | Pain persisting for at least 3 months after healing of herpes zoster skin rash, with average daily pain score of at least 40 mm/100 mm. Mean age 67 years, 50% male, 96% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin flexible dose (150-600 mg daily), n = 91 Fixed dose pregabalin 300 mg, n = 88 Placebo, n = 90 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R1, D2, W1 = 4/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Stated to be randomised |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “matching placebo” |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no enriched enrolment. 1-week titration for 300/600 mg (withdrawing those not able to reach target dose) (12 weeks total) | |

| Participants | Painful diabetic neuropathy for more than 1 year, and pain at least 40/100 mm. Mean age 59 years, 44% female, 96% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 150 mg daily, n = 99 Pregabalin 300 mg daily, n = 99 Pregabalin 600 mg daily, n = 101 Placebo daily, n = 96 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R1, D1, W1 = 3/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Stated to be randomised |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Stated to be double blind |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no enriched enrolment. 1-week titration for 300/600 mg (withdrawing those not able to reach target dose) (12 weeks total) | |

| Participants | Painful postherpetic neuralgia 6 months after healing of herpes zoster skin rash and pain of at least 40/100 mm or numerical rating of at least 4/11 at baseline. Mean age 71 years, 54% female, 99% white | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin 150 mg daily, n = 87 Pregablin 300 mg daily, n = 98 Pregablin 600 mg daily, n = 90 Placebo daily, n = 93 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R1, D1, W1 = 3/5 Pfizer sponsored |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | Stated to be randomised |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Not described |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Unclear | Stated to be double blind |

| Methods | Randomised, double blind, parallel group, no enriched enrolment. Flexible dosing regimen | |

| Participants | Severe central neuropathic pain lasting longer than 6 months, VAS more than 60/100 mm. Mean age 54 years, 48% female | |

| Interventions | Pregabalin to a maximum of 600 mg, n = 20 Placebo, n = 20 |

|

| Outcomes | Proportion of patients with ≥ 50% decrease in mean pain score between endpoint and baseline, and other outcomes | |

| Notes | Oxford quality score: R2, D2, W1 = 3/5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | “automated assignment system” |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | “blinded treating physician” |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | “identical capsules” |

D - double blind; n - number of participants; R - randomisation; W - withdrawals

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|