Abstract

Background

Adipose stem cells represent a heterogenous population. Understanding the functional characteristics of subpopulations will be useful in developing adipose stem cell–based therapies for regenerative medicine applications. The aim of this study was to define distinct populations within the stromal vascular fraction based on surface marker expression, and to evaluate the ability of each cell type to differentiate to mature adipocytes.

Methods

Subcutaneous whole adipose tissue was obtained by abdominoplasty from human patients. The stromal vascular fraction was separated and four cell populations were isolated by flow cytometry and studied. Candidate perivascular cells (pericytes) were defined as CD146+/CD31−/CD34−. Two CD31+ endothelial populations were detected and differentiated by CD34 expression. These were tentatively designated as mature endothelial (CD 31+/CD34−), and immature endothelial (CD31+/CD34+). Both endothelial populations were heterogeneous with respect to CD146. The CD31−/CD34+ fraction (preadipocyte candidate) was also CD90+ but lacked CD146 expression.

Results

Proliferation was greatest in the CD31−/CD34+ group and slowest in the CD146+ group. Expression of adipogenic genes, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, and fatty acid binding protein 4, were significantly higher in the CD31−/CD34+ group compared with all other populations after in vitro adipogenic differentiation. This group also demonstrated the highest proportion of AdipoRed lipid staining.

Conclusions

The authors have isolated four distinct stromal populations from human adult adipose tissue and characterized their adipogenic potential. Of these four populations, the CD31/CD34+ group is the most prevalent and has the greatest potential for adipogenic differentiation. This cell type appears to hold the most promise for adipose tissue engineering.

Stem cells exist at the undifferentiated stage with the ability to self-renew and differentiate into multiple cell types.1, 2 However, the use of embryonic stem cells faces ethical and legal challenges3; therefore, these cells are not as readily available for medical applications and research. Induced pluripotency techniques are very promising,4, 5 but safety concerns with the viral vectors used in the induction process limit clinical applications. It has been shown that stem cells isolated from adult tissues are able to self-renew and differentiate into multiple cell types along one germ layer.6, 7 Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells can be isolated from adult tissues,6 including bone marrow–derived stem cells.8, 9 Adipose tissue is plentiful, easy to harvest with minimally invasive liposuction techniques, and provides a rich source of adult stem cells. Although adipogenic progenitor cells have been isolated from stromal vascular fraction for over 40 years, adipose-derived stem cells were only described in the past decade.10, 11

Isolation of cells from adipose tissue yields a heterogeneous population containing multiple cell lines expressing different combinations of surface markers.12 The stromal vascular fraction of isolated adipose tissue has been used to reconstruct soft tissue with varying degrees of success.13–16 One explanation for the variable success rate may be the different functional properties of heterogeneous cell populations that comprise the stromal vascular fraction. In this study, we sought to isolate adipose-derived stem cell subpopulations using a multiparameter flow sorting strategy that includes the hematopoietic markers CD45 and CD3; the endothelial marker CD31; the perivascular marker CD146; and the stem/progenitor markers CD34, CD90, and CD117. We then identified the subpopulation with the greatest potential for adipogenic differentiation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Adipose Tissue Collection

Subcutaneous adipose tissue was harvested during elective abdominoplasties from human adult female patients (n = 5). All patients had body mass indices less than 35, were healthy, and did not suffer from diabetes. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved the procedure of collecting the samples of adipose tissue.

Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Isolation

Adipose tissue was minced with scissors, digested for 30 minutes in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) containing 3.5% bovine serum albumin (Millipore, Charlottesville, Va.) and 1 mg/ml collagenase type-II (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, N.J.) in a shaking water bath at 37°C, and disaggregated through successive 425-µm and 180-µm sieves (W.S. Tyler, Mentor, Ohio). Mature adipocytes were eliminated by centrifugation (400 g at ambient temperature for 10 minutes) and cell pellets were resuspended in ammonium chloride-based erythrocyte lysis buffer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, Fla.), incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature, and washed in phosphate-buffered saline. Viable cell enrichment and debris depletion was achieved with a Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient (Histopaque-1077; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.).

Flow Cytometry

Freshly isolated cells were kept on ice during the staining procedure. Cells were centrifuged (400 g for 7 minutes) and 5 µl of neat mouse serum (Sigma) was admixed to the cell pellet to minimize nonspecific antibody binding. Cells were incubated simultaneously with monoclonal mouse anti-human fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (2 µl each), CD3-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD146-phycoerythrin (PE), CD34-phycoerythrin-Texas red (ECD), CD90-PE-Cy5, and CD117-PE-Cy7, all from Beckman Coulter; and CD31- allophycocyanin (APC), and CD45-APC-Cy7 (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, Calif.). Cell sorting was performed using a three-laser Mo-Flo High-Speed Cell Sorter (Beckman Coulter). Spectral overlap compensation was manually achieved prior to cell sorting for each fluorescence parameter by using BD Calibrite beads (BD Biosciences) for single fluorochromatic molecules (FITC, PE, and APC) and antibody-stained mouse immunoglobulin G capture beads (BD Biosciences) for tandem-dyes (ECD, PE-Cy5, PE-Cy7, and ACP-Cy7). Eight-color-stained samples were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, supplemented with 2 µg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for exclusion of dead and apoptotic cells. Samples were cooled continuously at 4°C and four-way sorting was performed at 10,000 to 20,000 events per second. Samples were collected into chilled sterile polypropylene tubes over 500 µl of fetal calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Inc., Lawrenceville, Ga.).

Immunoblotting

Cultured adipose-derived stem cells were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline and lysed by adding 500 µl of lysis buffer containing 6M urea, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10% glycerol, 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 5% ß-mercaptoethanol, and 5 mg/ml bromophenol blue. The lysates were sonicated for 15-seconds using an ultrasonic processor (Heat Systems Ultrasonics, Inc., Farmingdale, N.Y.), and the supernatants were adjusted for equivalent protein concentrations, boiled, and subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The proteins were transferred to an Immobilon-P (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) membrane using a Bio-Rad MiniTrans-Blot Cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). The membrane was blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.05% Tween-20 for 1 hour and reacted overnight at 4°C with primary antibody. The membrane was then rinsed three times with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 and reacted with secondary antibody. Immunoblots were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence detection according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.), and images were taken by ChemiDoc (Bio-Rad). Protein expression levels were measured against β-actin by Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). The averages of all the patients were recorded. Normalized protein expression levels of each subpopulation were also compared against the unsorted group, as were the fold changes of protein expression levels of each subpopulation.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA isolated at days 7 and 14 was used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction. RNA was collected by means of the Qiagen RNeasy mini-kit. Approximately 200 ng of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the First Strand Transcription Kit (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The polymerase chain reaction primers were designed using the Vector NTI (Invitrogen) and synthesized by Invitrogen. Efficiency was checked from 10-fold serial dilutions of cDNA for each primer pair. A 2× SYBR Green PCR Mastermix (Invitrogen), 0.1 µM of each primer, and the cDNA template were mixed in 25-µl volumes. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed in triplicate in 96-well plates on Light Cycler 480 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind.). β-Actin was used as a control for quantitative polymerase chain reaction. All time points were compared relative to the unsorted cells.

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Statistical significance of data was analyzed with t tests.

Adipogenic Differentiation of the Subpopulations

Sorted adipose-derived stem cells were seeded at 80% confluence and cultured with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/F12 (1:1) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1% Fungizone (Invitrogen), and 0.05% dexamethasone until 100% confluence was reached. Growth media were replaced with differentiation media: 100 nM dexamethasone, 500 nM insulin, 200 pM T3, 0.5 µM ciglitazone, 540 µM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 33 µM biotin, 17 µM pantothenate, and 10 mg/ml transferrin. After 14 days, differentiated cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline and stained with 1% (volume/volume) AdipoRed (Zen-Bio, Research Triangle Park, N.C.) for 10 minutes; then, fluorescence was measured at 540 nm (Tecan SpectraFluor; Tecan, Inc., Research Triangle Park N.C.). Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and stained with 0.1% 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole solution. Adipogenic potential was determined by AdipoRed staining. Samples were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and imaged with an Olympus Flu-oview 1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, Pa.). The number of cells per low-power field (10× objective, five to eight fields) with at least five large AdipoRed vesicles was recorded for each culture and then analyzed with MetaMorph software (MDS Analytical Technologies, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Differentiation potential was calculated as the percentage of the cells with positive AdipoRed staining divided by the total number of cells with positive 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining in the same experiment. The fold changes were calculated by dividing absolute value of the unsorted group with that from each subpopulation.

Proliferation Assay

First, 1 × 103 adipose-derived stem cells were seeded 1000 cells/well onto 24-well plates for 24 hours (n = 3). Media were changed and cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline at indicated time points and frozen at −80°C. Cell proliferation rates were determined by measuring DNA content using CyQUANT kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Apoptosis Assay

For apoptosis assay, 2 × 104 adipose-derived stem cells from each subpopulation were seeded onto 96-well plates 24 hours before the experiment (n = 3). Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline twice and treated with apoptosis inducer 1 µM staurosporine for 24 hours. Exposed histones were measured using the Cell Death Detection ELISA kit (Roche, Nutley, N.J.) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Osteogenic Differentiation

Osteogenic cultures were adapted from published data.17 Briefly, expanded adherent adipose-derived stem cells were trypsinized and plated onto 24-well plates (50,000 cells/well). After cells were allowed to adhere overnight, culture medium was supplemented with 0.1 µM dexamethasone, 50 µg/ml L-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, and 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 21 days. Cells were fixed in 2% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 15 minutes at room temperature. Alkaline phosphatase activity was assessed using the Leukocyte Alkaline Phosphatase kit (Sigma-Aldrich). For alizarin red calcium staining, fixed cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline and stained for 10 minutes with 30 mM alizarin red-S (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The presence of calcium was documented using microscopy.

Chondrogenic Differentiation

Chondrogenic cell pellet cultures were adapted from published data.18 Briefly, 200,000 trypsinized expanded (P3) cells were transferred into a 15-ml polypropylene BD Falcon conical tube, centrifuged for 10 minutes at 400 g, and kept overnight. Culture medium was replaced by Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium high glucose, supplemented with ITS+ Premix (Becton Dickinson), 40 µg/ml L-Proline (Sigma), 50 µg/ml 2-phospho-L-ascorbic acid trisodium (Fluka-Chemie AG, Buchs, Switzerland), 10 ng/ml transforming growth factor-β1 (PreproTech, Rocky Hill, N.J.), and 100 ng/ml bone morphogenetic protein 6 (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, Calif.). After 21 days, cell pellets were fixed and stained for 30 minutes in Alcian blue solution (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, Mich.). The presence of proteoglycans was documented using bright-field microscopy.

RESULTS

Isolation of Four Different Nonhematopoietic Subpopulations from the Stromal Vascular Fraction

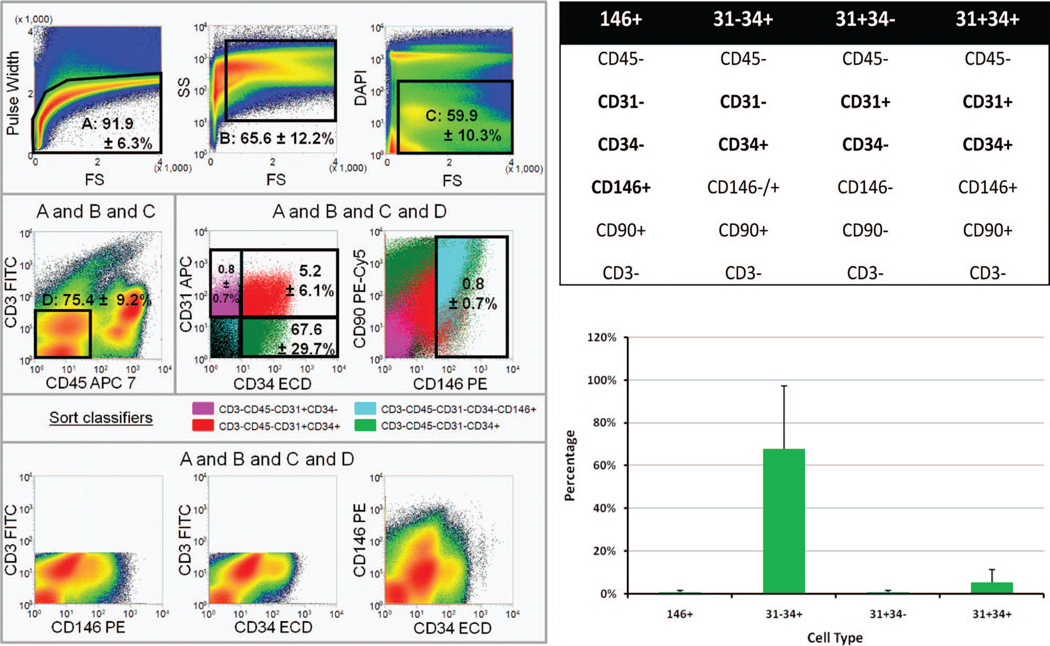

A gating strategy for sorting on an eight-color Mo-Flo Legacy cell sorter was developed. Forward scatter pulse height and side scatter analyses were performed to exclude cell clusters. Exclusion of the DNA stain 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole was used to identify viable cellular events. A CD3-FITC dump gate was used to exclude autofluorescent events and CD45 to eliminate hematopoietic cells. Among CD45− nonhematopoietic cells, we were able to detect four stromal vascular populations as shown in Figure 1: endothelial mature (pink), endothelial progenitor (red), pericyte (orange), and preadipocyte (green) populations. Endothelial populations were defined as described previously by our group19 according primarily to CD31 expression. Based on the definition above, the highest percentage of subpopulation cells within viable stromal vascular fractions is CD31− CD34+ (67.60 ± 29.7 percent), CD31+/CD34+ is the second most abundant subpopulation with 5.2 ± 6.1 percent, and CD146+ cells appear at 0.8 ± 0.7 percent.

Fig. 1.

(Above, left, center, left, and below, left) Classification of endothelial, pericyte, and preadipocyte populations for flow cytometric sorting. Cells were sorted on an eight-color Beckman Coulter MoFlo Legacy high-speed sorter. Histograms from a representative sort file are shown. Region percentages of gated cells represent the mean of five independent sorts ± 1 SD. (Above, left, left to right) Single cells (A) were isolated from cell clusters using forward scatter pulse height; events with very low forward scatter were eliminated; viable cells exclude the DNA stain 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole(C).(Center, left, left to right) Nonhematopoietic cells (D) were defined by the absence of CD45 and CD3. Four sort populations were defined among nonhematopoietic cells on the basis of CD34, CD31, and CD146 expression. Color eventing is used to compare marker expression on the four sort populations. Two distinct CD31+ endothelial populations were successfully isolated (CD31+ CD34− and CD31+ CD34+, color-evented pink and red, respectively), as previously reported (Zimmerlin L, Donnenberg VS, Pfeifer ME, et al. Stromal vascular progenitors in adult human adipose tissue. Cytometry A 2010;77:22-30). Within each endothelial group, the cell populations were homogenous with respect to CD90 and CD146 expression, as determined by color evented populations. Nonendothelial cells were separated as CD3− CD45− CD31− CD34− CD146+ pericytes (orange) and preadipocytes, a population representing the CD34+ cells among CD31− nonhematopoietic cells (green). (Below, left) Defining nonhematopoietic cells as negative for CD3-FITC (dump gate) was effective in eliminating autofluorescent events from the sort populations, as indicated by the absence of a diagonal population in the below, right panel. (Above, right) Cell surfaces markers used in cell sorting process. (Below, right) Percentage of each subpopulation from the viable stromal vascular fractions. Average of five patients is shown.

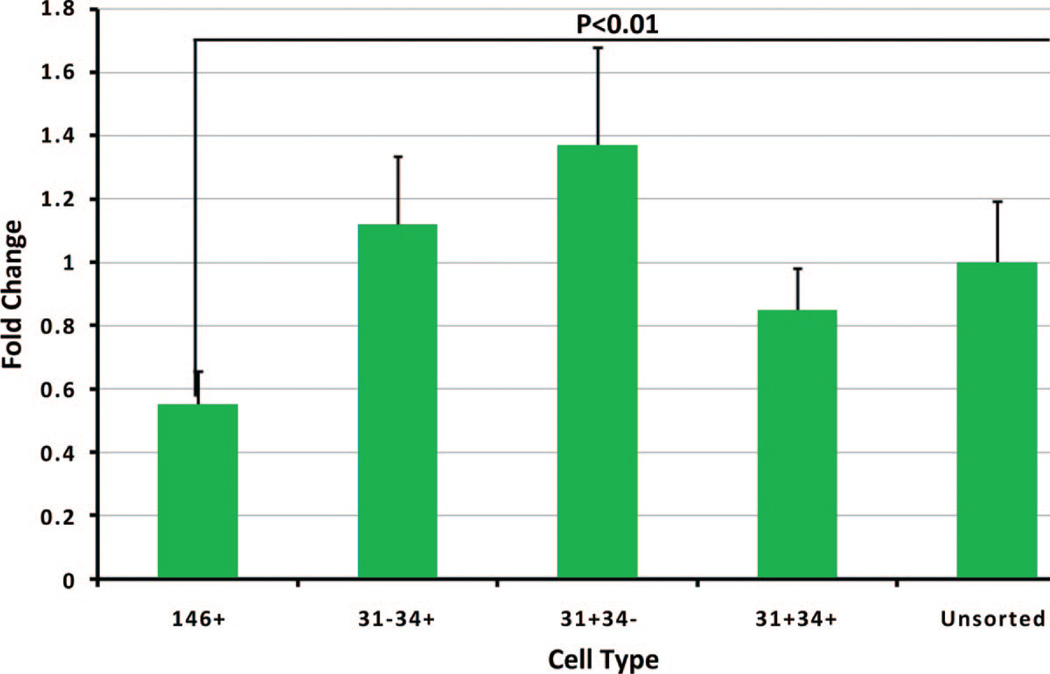

Proliferation of Sorted Subpopulations

Proliferation rates were determined using Cy-QUANT, which directly measures DNA content in each sample. Cells from all subpopulations were able to proliferate, although with different rates, as shown in Figure 2. The proliferation rates trended faster in the preadipocyte (CD31−/CD34+) and endothelial mature (CD31+/CD34−) subpopulations compared with the unsorted group without statistical significance. Proliferation was significantly slower in the pericyte (CD45−/CD31−/CD34−/CD146+/CD90+/−) subpopulation, with statistical significance, as compared with all other groups.

Fig. 2.

Proliferation rates of each subpopulation. Growth rates of each subpopulation were measured by CyQUANT Assay. Growth rates relative to unsorted adipose-derived stem cells were plotted on the y axis.

Apoptosis Resistance of Sorted Subpopulations

To test the resistance to apoptosis, each subpopulation was treated with an apoptosis-inducing drug staurosporine (1 µM), for 24 hours, and exposed histones were determined as an indicator of apoptosis. Of all subpopulations, including the unsorted group from the same isolation, the pericyte (CD146+) group demonstrated the greatest resistance to apoptosis, which was significantly different from all other groups (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the other subpopulations did not demonstrate any significant differences when compared with the unsorted group.

Fig. 3.

Apoptotic resistance for each subpopulation. The subpopulations and unsorted group were treated with staurosporine (1 µM) for 24 hours. Exposed histones were measured with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Fluorescence readings relative to unsorted adipose-derived stem cells were plotted on the y axis.

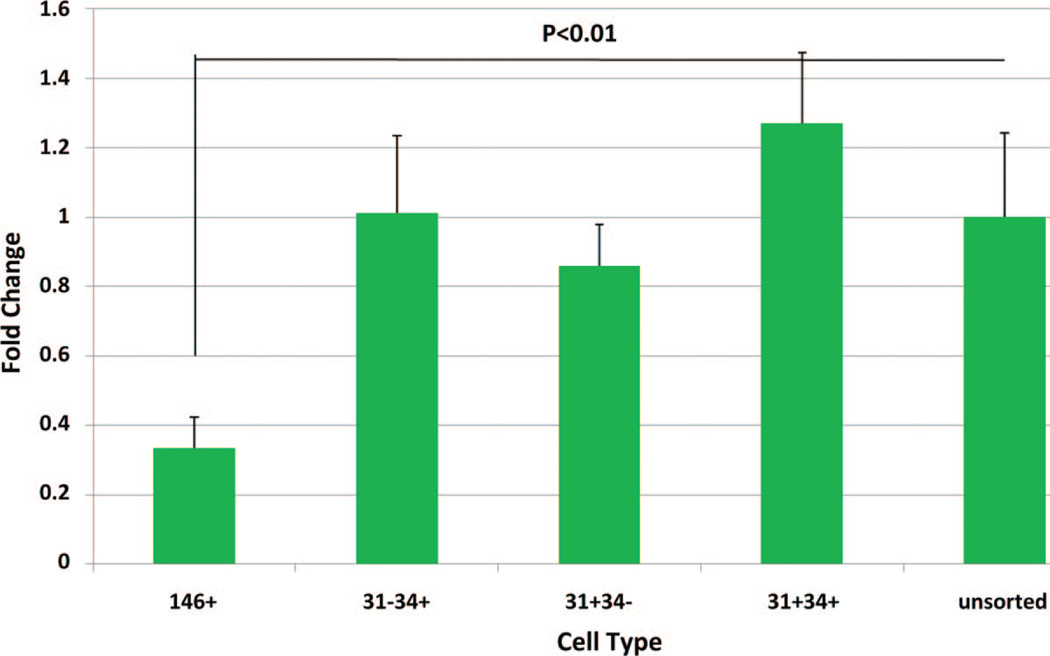

Adipogenic Differentiation of the Sorted Subpopulations

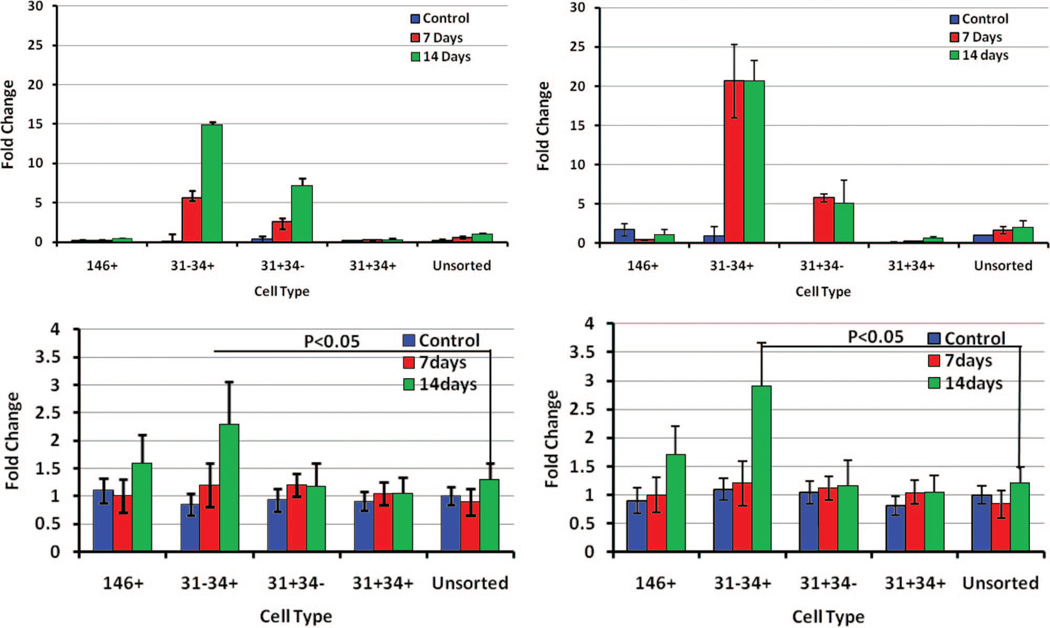

Consistent with the hypothesis that different sub-populations will manifest variable functional behavior, we observed clear differences in adipogenic potential and identified a cell population with a much higher potential for differentiation to the adipose phenotype. Subpopulations were cultured in adipogenic differentiation medium, and the adipogenic differentiation potential was determined by adipogenic gene expression and AdipoRed staining. The highest incidence of positive AdipoRed staining was noted in the CD31−/CD34+ (presumptive preadipocytes) group (Fig. 4). After exposure to adipogenic medium, a 2.7-fold increase in fluorescence signal was observed compared with the unsorted group with AdipoRed (p < 0.01). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ mRNA expression was significantly higher in the preadipocyte (CD31−/CD34+) group compared with all other populations (15-fold increase compare with the unsorted group (Fig. 5). The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ mRNA expression increased from day 7 to day 14 after exposure to adipogenic medium. A disproportionately high expression of fatty acid binding protein 4 mRNA, a downstream target of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ and an early marker of adipogenesis, was also observed in this group (a 20-fold increase compare with the unsorted group). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ and leptin, another adipogenic differentiation marker, were increased significantly at protein level as shown in Figure 5, below (an average 2.3-fold increase in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ protein and a 2.9-fold increases in leptin protein expression). Based on lipid accumulation and adipogenic markers, the presumptive preadipocyte subpopulation (CD31−/CD34+) demonstrated the greatest potential toward adipogenesis when compared with any other subpopulation (Fig. 6).

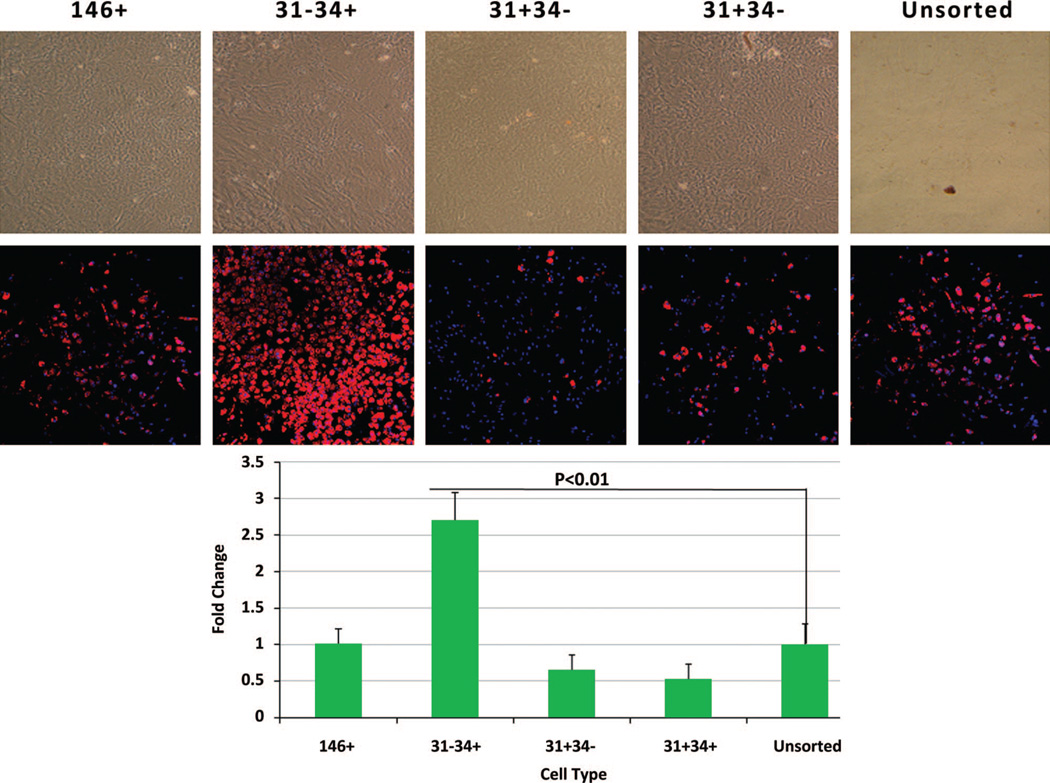

Fig. 4.

Adipogenic differentiations of the subpopulations. All the subpopulations and the unsorted cells were exposed to adipogenic differentiation medium for 14 days. Lipid accumulation was determined with AdipoRed (above). Fluorescence density of AdipoRed plate is shown (below).

Fig. 5.

Adipogenic gene expression. The subpopulations and unsorted cells were exposed to adipogenic differentiation medium for 7 days and 14 days, and adipogenic gene expression was measured. (Above, left) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ mRNA expression measured with quantitative polymerase chain reaction. (Above, right) Fatty acid binding protein 4 measured with quantitative polymerase chain reaction. (Below, left) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ protein expression levels were measured with signal densities and plotted against unsorted cells on the y axis. (Below, right) Leptin protein expression levels were measured with signal densities and plotted against unsorted cells on the y axis.

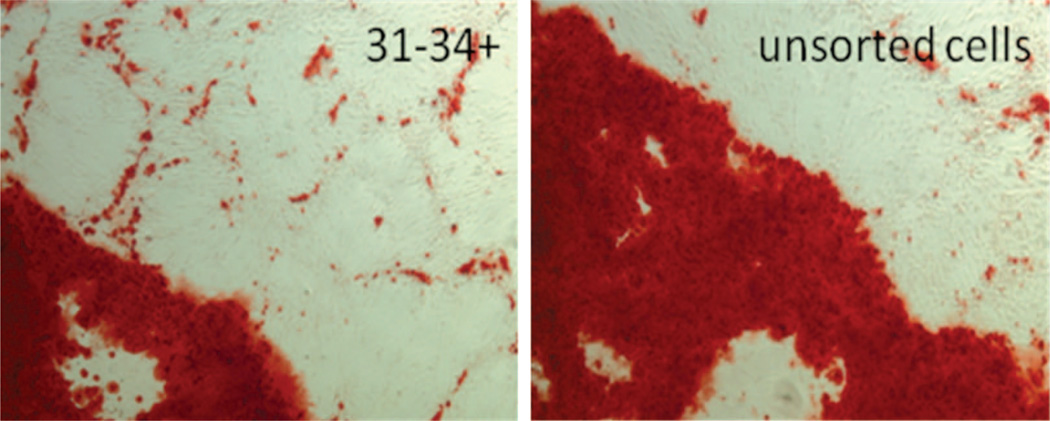

Fig. 6.

Osteogenic differentiation determined with alizarin red staining.

Chondrogenic and Osteogenic Differentiation of Sorted Subpopulations

Multilineage potential of the sorted sub-populations was confirmed by demonstrating osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation. Osteogenic differentiation potentials of sorted subpopulations were determined with alkaline phosphatase activity and alizarin red staining for calcium deposition. Chondrogenic differentiation potentials were determined with Alcian blue staining. All sorted subpopulations demonstrated increased alkaline phosphatase activity after differentiation under osteogenic conditions but had variable efficiency for terminal differentiation as demonstrated by alizarin red calcium staining. The preadipocytes demonstrated a lower amount of calcium deposition than the unsorted fraction. Among the subpopulations, the endothelial mature cell fraction demonstrated the lowest ability to develop calcium deposits. The decreased ability to develop calcium deposits in the preadipocyte and endothelial mature groups was significant relative to the unsorted group (p < 0.5). Pericytes and endothelial progenitors had intermediate osteogenic differentiation potential under our differentiation protocol. Both pericytes and preadipocytes showed the ability to differentiate toward the chondrogenic lineage, with more positive staining for Alcian blue detected than in the endothelial populations (data not shown). However, there were no significant differences between groups with respect to chondrogenic differentiation.

DISCUSSION

Adipose-derived stem cells, similar to bone marrow stem cells, have a mesenchymal origin and can be differentiated into different cell types20–24; moreover, adipose-derived stem cells can be harvested abundantly from a patient by means of a relatively noninvasive procedure. However, adipose-derived stem cells represent a heterogeneous population of cells.10, 11 Different strategies and various cell surface markers have been used to isolate subpopulations from adipose-derived stem cells.25–27 Traktuev et al., isolated a population with cell surface markers CD34+/CD31−/CD144− from the stromal vascular fraction and demonstrated that greater than 90 percent coexpress mesenchymal (CD10, CD13, and CD90), pericytic (chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, CD140a, and CD140b), and smooth muscle (α-actin, caldesmon, and calponin) markers.25 The isolated adipose-derived stem cells demonstrated polygonal self-assembly on Matrigel (BD Biosciences), and coculture of isolated adipose-derived stem cells with human microvascular endothelial cells on Matrigel led to cooperative network assembly, and preferential localization of isolated adipose-derived stem cells on the luminal side of cords. Zannettino et al. investigated the putative niche of adipose-derived stem cells using a different set of cell surface markers, including STRO-1, CD146, and 3G5.26 They described a multipotential stem cell population within adipose, which also appeared to be intimately associated with perivascular cells surrounding the blood vessels. Although both groups reported that a perivascular fraction was isolated, different sets of cell surface markers were used. It is possible that there was some overlap in their marker choice. Suga et al. separated adipose-derived stem cells into two groups based on CD34.27 The CD34+ population was more proliferative and had a greater ability to form colonies. Expression levels of endothelial progenitor markers (Flk-1, FLT1, and Tie-2) were higher in CD34+ cells, whereas those of pericyte markers (CD146, NG2, and α-smooth muscle actin) were higher in CD34− cells. Expression levels of growth factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor, before and after hypoxia treatment, were similar. Crisan et al. demonstrated that pericytes exist in multiple organs, including adipose tissue.28 These cells express CD146, NG2, and platelet-derived growth factor-Rβ, and are negative for hematopoietic, endothelial, and myogenic cell markers. Although pericytes have been identified within adipose tissue,29, 30 different sets of cell surface markers were used to isolate the cells, indicating that a thorough analysis of cell sub-populations is needed and a more defined method is required to identify these subpopulations.

To identify which subpopulation had the most adipogenic differentiation potential in the stromal vascular fraction, we designed a strategy to isolate subpopulations by using a combination of cell surface markers. Subsequently, we successfully identified, isolated, expanded, and examined the multipotencies of the sorted subpopulations.

Two nonhematopoietic endothelial subpopulations were identified based on the expression of CD31 and CD34. The subpopulation CD31+/ CD34+ was defined as the “endothelial progenitor subpopulation” and was the more prevalent of the two endothelial populations. Conversely, the CD31+/CD34− subpopulation was defined as the “endothelial mature subpopulation,” and is consistent with bone marrow and circulating endothelial progenitor cells in the literature.31–33 However, the higher frequency of this population in adipose tissue renders these cells a potentially excellent source for regenerative medicine.34, 35 Similar to the definition used by others,28 pericytes were defined as CD45−/CD34−/CD31−/CD146+/CD90+, and comprised only 0.8 ± 0.7 percent (mean ± SD) of all the nucleated stromal vascular fraction cells. The most abundant subpopulation was CD45−/ CD31−/CD34+/CD146− cells (>90 percent CD90+), defined as “preadipocytes.” This subpopulation was similar to the population identified using the less-descriptive term “adipose-derived stem cells.”27

Proliferation rates and resistance to apoptosis were determined in each subpopulation. The pericyte-like cells showed a significant difference in proliferation when compared with the unsorted group. Resistances of these subpopulations to apoptosis also varied when exposed to an apoptosis-inducing agent. These differences among the subpopulations indicated that they not only express different cell surface markers but also vary in physiologic behavior. Proliferation rates and resistance to apoptosis are also important in the clinical application of these cell types in regenerative medicine, especially in soft-tissue reconstruction. Cell types with slower proliferation rates or increased vulnerability to apoptosis may not survive harvest and implantation.

Multipotency was examined by exposing sub-populations to adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation medium. The relative potential to express phenotypic characteristics of each lineage was different. Multipotency was preserved in all subpopulations. Our presumptive “preadipocyte” population (CD31−/CD34+) showed the most adipogenic potential and less osteogenic differentiation propensity, indicating a true preadipocyte population. The preadipocyte population also demonstrated the highest expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ after exposure to the adipogenic medium. Leptin and fatty acid binding protein 4 also had the highest expression level in the preadipocyte population. Most significantly, this group showed the highest level of fatty acid accumulation as demonstrated by AdipoRed staining. There were no differences with chondrogenic differentiation propensity among the isolated subpopulations. It is interesting to note that even the subpopulation expressing CD31+ without the presence of CD34+ antigens, which may have been assumed to have a mature endothelial phenotype, still had multilineage potential, including adipogenesis. Although there were likely to have been mature endothelial cells in that group, there were still progenitor cells present.

The pericyte subpopulation did show strong multilineage potential but did not match the preadipocyte group in terms of adipogenic potential. It should be noted, however, that the cell-sorting strategy yielded a distinct pericyte population that was CD146+ but CD34−, and subgroup analysis of CD34+/CD146+ was not performed in this study. Prior work by our group suggests that further distinctions in adipogenic capacity can be made among subgroups in the preadipocyte population and that CD34+/CD146+ cells are worth investigating in future studies.19 Overall, the CD45−/ CD31−/CD34+ cells represent a subpopulation with an inherent propensity for adipogenesis far beyond that of other stromal cell populations. The cell population we have isolated based on CD31/ CD34+ surface marker expression stands out as the true “preadipocyte” phenotype.

Our study supports the hypothesis that subpopulations expressing different cell surface markers have different intrinsic properties and coexist in the stromal vascular fraction, and that there is a true “preadipocyte” subpopulation. This subpopulation has characteristics inherent in preadipocytes, namely, the expression of high levels of adipocyte markers and, more importantly, lipid accumulation after exposure to adipogenic medium. Identification of this subpopulation within the stromal vascular fraction will allow us to study adipogenic differentiation and its application in regenerative medicine using a more focused cell population and resulting in more defined outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thankfully acknowledge the Center for Biologic Imaging for scanning electron microscopic analysis and National Institutes of Health grant R01CA114246-01A1 (J.P.R.). They wish to acknowledge Melanie Pfiefer for expert technical assistance. They also acknowledge funding from grants BC032981 and BC044784 from the Department of Defense, the Hillman Foundation, and the Glimmer of Hope Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zipori D. The nature of stem cells: State rather than entity. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:873–878. doi: 10.1038/nrg1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson JA. Human embryonic stem cell research: Ethical and legal issues. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:74–78. doi: 10.1038/35047594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissman IL. Stem cells: Units of development, units of regeneration, and units in evolution. Cell. 2000;100:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Clevers H. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science. 2010;327:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.1180794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodell MA, Brose K, Paradis G, Conner AS, Mulligan RC. Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1797–1806. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baum CM, Weissman IL, Tsukamoto AS, Buckle AM, Peault B. Isolation of a candidate human hematopoietic stem-cell population. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2804–2808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: Implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:211–228. doi: 10.1089/107632701300062859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4279–4295. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrison WA. Progress in tissue engineering of soft tissue and organs. Surgery. 2009;145:127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bacou F, el Andalousi RB, Daussin PA, et al. Transplantation of adipose tissue-derived stromal cells increases mass and functional capacity of damaged skeletal muscle. Cell Transplant. 2004;13:103–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowan CM, Shi YY, Aalami OO, et al. Adipose-derived adult stromal cells heal criticalsize mouse calvarial defects. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:560–567. doi: 10.1038/nbt958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guilak F, Awad HA, Fermor B, Leddy HA, Gimble JM. Adipose-derived adult stem cells for cartilage tissue engineering. Biorheology. 2004;41:389–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mauney JR, Nguyen T, Gillen K, Kirker-Head C, Gimble JM, Kaplan DL. Engineering adipose-like tissue in vitro and in vivo utilizing human bone marrow and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells with silk fibroin 3D scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5280–5290. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Girolamo L, Sartori MF, Albisetti W, Brini AT. Osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells: Comparison of two different inductive media. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2007;1:154–157. doi: 10.1002/term.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estes BT, Wu AW, Guilak F. Potent induction of chondrocytic differentiation of human adipose-derived adult stem cells by bone morphogenetic protein 6. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1222–1232. doi: 10.1002/art.21779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerlin L, Donnenberg VS, Pfeifer ME, et al. Stromal vascular progenitors in adult human adipose tissue. Cytometry A. 2010;77:22–30. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timper K, Seboek D, Eberhardt M, et al. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into insulin, somatostatin, and glucagon expressing cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:1135–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo MJ, Suh SY, Bae YC, Jung JS. Differentiation of human adipose stromal cells into hepatic lineage in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Safford KM, Hicok KC, Safford SD, et al. Neurogenic differentiation of murine and human adipose-derived stromal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:371–379. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Planat-Bénard V, Menard C, André M, et al. Spontaneous cardiomyocyte differentiation from adipose tissue stroma cells. Circ Res. 2004;94:223–229. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000109792.43271.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogawa R, Mizuno H, Watanabe A, Migita M, Shimada T, Hyakusoku H. Osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation by adipose-derived stem cells harvested from GFP transgenic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313:871–877. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Traktuev DO, Merfeld-Clauss S, Li J, et al. A population of multipotent CD34-positive adipose stromal cells share pericyte and mesenchymal surface markers, reside in a perien-dothelial location, and stabilize endothelial networks. Circ Res. 2008;102:77–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.159475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zannettino AC, Paton S, Arthur A, et al. Multipotential human adipose-derived stromal stem cells exhibit a perivascular phenotype in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Physiol. 2008;214:413–421. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suga H, Matsumoto D, Eto H, et al. Functional implications of CD34 expression in human adipose-derived stem/progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:1201–1210. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, et al. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crisan M, Chen CW, Corselli M, Andriolo G, Lazzari L, Péault B. Perivascular multipotent progenitor cells in human organs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1176:118–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CW, Montelatici E, Crisan M, et al. Perivascular multi-lineage progenitor cells in human organs: Regenerative units, cytokine sources or both? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tárnok A, Ulrich H, Bocsi J. Phenotypes of stem cells from diverse origin. Cytometry A. 2010;77:6–10. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeoli A, Dentelli P, Brizzi MF. Endothelial progenitor cells and their potential clinical implication in cardiovascular disorders. J Endocrinol Invest. 2009;32:370–382. doi: 10.1007/BF03345729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tilki D, Hohn HP, Ergün B, Rafii S, Ergün S. Emerging biology of vascular wall progenitor cells in health and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murohara T, Shintani S, Kondo K. Autologous adipose-derived regenerative cells for therapeutic angiogenesis. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:2784–2790. doi: 10.2174/138161209788923796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madonna R, De Caterina R. Adipose tissue: A new source for cardiovascular repair. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2010;11:71–80. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e328330e9be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]