Abstract

Calcium operates by several mechanisms to regulate glutamate release at rod and cone synaptic terminals. In addition to serving as the exocytotic trigger, Ca2+ accelerates replenishment of vesicles in cones and triggers Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) in rods. Ca2+ thereby amplifies sustained exocytosis, enabling photoreceptor synapses to encode constant and changing light. A complete picture of the role of Ca2+ in regulating synaptic transmission requires an understanding of the endogenous Ca2+ handling mechanisms at the synapse. We therefore used the “added buffer” approach to measure the endogenous Ca2+ binding ratio (κendo) and extrusion rate constant (γ) in synaptic terminals of photoreceptors in retinal slices from tiger salamander. We found that κendo was similar in both cell types - approximately 25 and 50 in rods and cones, respectively. Using measurements of the decay time constants of Ca2+ transients, we found that γ was also similar, with values of approximately 100 s−1 and 160 s−1 in rods and cones, respectively. The measurements of κendo differ considerably from measurements in retinal bipolar cells, another ribbon-bearing class of retinal neurons, but are comparable to similar measurements at other conventional synapses. The values of γ are slower than at other synapses, suggesting that Ca2+ ions linger longer in photoreceptor terminals, supporting sustained exocytosis, CICR, and Ca2+-dependent ribbon replenishment. The mechanisms of endogenous Ca2+ handling in photoreceptors are thus well-suited for supporting tonic neurotransmission. Similarities between rod and cone Ca2+ handling suggest that neither buffering nor extrusion underlie differences in synaptic transmission kinetics.

Keywords: Retina, photoreceptor, calcium buffering, added buffer, synapse, synaptic ribbon, calcium extrusion

Introduction

Absorption of photons in the outer segments of rod and cone photoreceptors triggers a change in membrane voltage that regulates the rate of vesicle fusion at synapses onto second-order horizontal and bipolar cells. Calcium (Ca2+) influx through CaV1.4 L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels is the key signal responsible for making this transformation (Bader et al., 1982; Corey et al., 1984; Maricq and Korenbrot, 1988; Barnes and Hille, 1989; Wilkinson and Barnes, 1996; Morgans et al., 2005). The exocytotic Ca+ sensor in photoreceptor terminals is especially sensitive to Ca2+, triggering fusion at a threshold of ~400 nM with a low cooperativity of n = 2 (Thoreson et al., 2004; Duncan et al., 2010). Additionally, the close spacing of Ca2+ channels beneath the synaptic ribbon and in proximity to ribbon-tethered vesicles means that fusion of a single vesicle is highly efficient and can be triggered by the opening of only 2–3 Ca2+ channels in cones (Bartoletti et al., 2011). Other important processes in photoreceptor synaptic terminals are also regulated by Ca2+. For instance, Ca2+ accelerates the resupply of releasable vesicles to the cone ribbon and in so doing, regulates the rate of sustained release (Babai et al., 2010a). Differences in Ca2+ buffering might also contribute to the slower release kinetics observed in rods compared to cones (Cadetti et al., 2005; Rabl et al., 2005; Thoreson, 2007). In rods, increased Ca2+ influx slows endocytosis (Cork and Thoreson, 2014). Moreover, Ca2+ ions can directly gate or modulate the gating properties of a variety of photoreceptor ionic conductances, thereby altering photoreceptor voltage responses and synaptic output (Barnes and Hille, 1989; Thoreson et al., 2002; Malcolm et al., 2003). Thus, the precise spatiotemporal control of Ca2+ is key in regulating the transmission of photoreceptor light responses at the first synapse in the visual pathway.

After Ca2+ ions enter the terminal, a fraction are quickly bound by endogenous buffers while the remainder contribute to free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]Free) (Rusakov, 2006). Ca2+ ions are also extruded or taken up by other intracellular organelles (Rusakov, 2006). Many studies that seek to understand the spatiotemporal dynamics of Ca2+ signaling in photoreceptor terminals do so using fluorescent Ca2+ indicators. These indicators, however, typically compete for Ca2+ binding with endogenous Ca2+ buffering molecules, making it difficult to study the endogenous characteristics of Ca2+ handling in photoreceptor terminals. In this study, we used the “added buffer” approach (Neher and Augustine, 1992; Helmchen et al., 1996) to examine how Ca2+ is regulated at photoreceptor synaptic terminals. We found that the endogenous binding ratio (κendo), which represents the fraction of entering Ca2+ ions bound by endogenous buffers and therefore unable to contribute to the [Ca2+]Free, is relatively low in both cones and rods. This approach also allowed us to measure an endogenous extrusion rate (γ), which was also similar at rod and cone terminals, but slightly slower than values for γ reported at other presynaptic terminals.

Materials and Methods

Salamander retinal slice preparation

Experiments were performed using retinas of aquatic tiger salamanders (Ambystoma tigrinum),18–25 cm in length (Charles Sullivan, Nashville, TN). Care and handling protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Animals were housed on a 12 h light/dark cycle at 4–8° C. One to two hours after the beginning of the dark cycle, animals were immersed in the anesthetic MS222 (0.25 g/L) for 10–15 min. They were then decapitated, quickly pithed, and enucleated. Retinal slices were prepared as described previously (Van Hook and Thoreson, 2013). Briefly, the anterior segment of the eye, including the lens, was removed and the resulting eyecup was cut into quarters. One or two pieces were placed vitreal side down on a nitrocellulose membrane (5 x 10 mm; type AAWP, 0.8 μm pores; Millipore). The nitrocellulose membrane with pieces of eyecup was submerged in cold amphibian saline and the sclera was gently peeled away, leaving the retina adhering to the membrane. The retina was then cut into 125 μm slices using a razor blade tissue slicer (Stoelting). Slices were rotated 90 degrees to view the retinal layers and anchored in the recording chamber by embedding the ends of the nitrocellulose membrane in vacuum grease.

Experiments were performed on an upright fixed-stage microscope (Nikon E600FN) equipped with a 60x water-immersion objective, spinning disk laser confocal scan head (PerkinElmer UltraView LCI), and a cooled CCD camera (Orca ER). The spinning disk confocal provides high time resolution at lower laser light levels, making this system advantageous for physiological measurements such as those conducted in this study. Slices were superfused at ~1 ml/minute with an oxygenated amphibian saline solution containing the following (in mM): 116 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2; 0.5 MgCl2; 5 glucose, and 10 HEPES. The pH was adjusted to 7.8 with NaOH. Osmolarity was measured with a vapor pressure osmometer (Wescor) and adjusted to 240–245 mOsm.

Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass (1.2 mm OD, 0.9 mm ID, with an internal filament; World Precision Instruments) using a PC-10 vertical pipette puller (Narishige) and had resistances of 15–20 MΩ. The standard pipette solution for cones contained (in mM): 90 Cs Gluconate, 10 TEA-Cl, 3.5 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 ATP-Mg, 0.5 GTP-Na, 10 HEPES, 0.1 Alexa Fluor 568 hydrazide (Life Technologies), and 0.2 Fluo5F (pentapotassium salt; Life Technologies). The pH was adjusted to 7.2 and the osmolarity was adjusted to 235–240 with CsOH.

Ca2+ imaging

Rods and cones were targeted for whole cell patch-clamp recording based on morphology and were filled with both a Ca2+-sensitive dye (Fluo5F, 200 μM) and a Ca2+-insensitive dye (Alexa568, 100 μM) as the cells were dialyzed with the pipette solution following rupture of the membrane patch.

We used a ratiometric approach to calculate the amplitude of free Ca2+ transients in rod and cone synaptic terminals in response to brief depolarizations. Because the molecular of weights Fluo5F and Alexa568 are similar, they diffuse into the cell through the patch pipette at roughly the same rate (see below). Thus, although the absolute intracellular concentration of each increased gradually after breaking in, the relative concentrations remained nearly constant over the course of the experiment.

We measured the background-subtracted fluorescence signal of the Ca2+-sensitive dye, Fluo5F (FFluo) in response to a brief depolarization (75 ms to −25 mV for rods and 125 ms to −10 mV for cones). These measurements were interspersed with background-subtracted fluorescence measurements of Alexa568 fluorescence (FAlexa) at 30–60 s intervals. We fit the FAlexa measurements over the time course of a recording with a monoexponential function to measure the time constant of dye diffusion into the terminal. This enabled us to compute the ratio of the Ca2+-sensitive and Ca2+-insensitive fluorescence (FFluo/FAlexa) by interpolating with the exponential function to provide a measure of FAlexa at the time point in which we recorded the FFluo response.

We calibrated the fluorescence ratio using a set of Ca2+ standards (Molecular Probes). This gave us an effective Kd for Fluo5F of 1.35 μM, similar to the Kd provided by the manufacturer (2.3 μM, Life Technologies) and a (FFluo/FAlexa)max of 0.3964.

These parameters enabled us to calculate the amplitude of free Ca2+ transients (A) using the following equation:

| (Equation 1) |

Added buffer approach

We used the “added buffer” method (Neher and Augustine, 1992; Helmchen et al., 1996) to measure the endogenous Ca2+ binding ratio (κendo) in rod and cone terminals. As rods and cones are dialyzed with a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator (Fluo5F, in this case), that indicator competes with endogenous Ca2+ buffers so that free Ca2+ is determined by a chemical equilibrium between Ca2+ ions, bound and unbound endogenous buffers, and the bound and unbound exogenous Ca2+ indicator.

To estimate the contribution of the Fluo5F to the buffering capacity, we calculated an incremental binding ratio of the indicator dye (κ′exo) (Neher and Augustine, 1992; Helmchen et al., 1996, 1997):

| (Equation 2) |

where Kd is the effective dissociation constant for Fluo5F (1.35 μM, above), [Ca2+]rest is the resting free Ca2+ concentration, and [Ca2+]peak was the peak amplitude of the free Ca2+ transient. From the fluorescence ratio FFluo/FAlexa, we found that [Ca2+]rest averaged 77 ± 17 nM in rods (n = 14) and 77 ± 11 nM in cones (n = 10) voltage-clamped at −70 mV, consistent with previous measurements (Steele et al., 2005; Szikra and Krizaj, 2007; Choi et al., 2008; Mercer et al., 2011). [Fluo5F] is the concentration of Fluo5F determined from a monoexponential fit of FAlexa measured periodically during the experiment (above) with the assumption that it will plateau when [Fluo5F] and [Alexa568] in the terminal are equal to their concentrations in the pipette solution (200 μM and 100 μM, respectively). To ensure that we could indeed use the gradual increase in FAlexa to determine [Fluo5F], we measured the relative time constants of loading rods and cones with each dye. To accomplish this, we incubated retinal slices in 10 μM BAPTA-AM for 1 hour. The tissue was then superfused with a Ca2+-free amphibian saline (containing 2.3 mM Mg2+ and 1 mM EGTA) and rods and cones were targeted for whole cell recording with a pipette solution containing 100 μM Alexa568, 200 μM Fluo5F, 16 mM BAPTA, and no added Ca2+ to ensure that the weak fluorescence signals associated with Fluo5F were Ca2+-independent. Measured this way, the time constant of the increase in Fluo5F fluorescence following establishment of whole-cell recording configuration was 15 ± 29% slower than the increase in Alexa568 fluorescence in rod terminals (N = 6) and 10 ± 11% slower in cone terminals (N = 5). Consistent with these measurements, the higher molecular weight of Fluo5F (931) predicts a diffusion coefficient that is 8% slower than Alexa 568 (molecular weight 730.7). Thus, although the time constants for increases in FFluo and FAlexa were not significantly different (p = 0.87 for cones and p = 0.49 for rods, paired t-test), we scaled the time constant of the increase in FAlexa by 10% for cones and 15% for rods to determine [Fluo5F].

The time constant of decay for the Ca2+ transient (τ) is dependent on the total Ca2+ binding ratio in the terminal (Neher and Augustine, 1992; Helmchen et al., 1996):

| (Equation 3) |

where γ is the rate constant of extrusion, which results from the transport of Ca2+ ions across the membrane or by sequestration into intracellular organelles. Additionally, the amplitude of the free Ca2+ transient (A) is inversely dependent on the total Ca2+ binding ratio:

| (Equation 4) |

The additional Ca2+ buffering resulting from Fluo5F thus reduces the amplitude and slows the recovery of free Ca2+ transients (Neher and Augustine, 1992). By gradually increasing [Fluo5F] in the terminal - in this case, by diffusion from the patch pipette during the course of a whole-cell recording - and thereby gradually increasing κ′exo while monitoring the amplitude and kinetics of free Ca2+ transients, we extrapolated our measurements to estimate the κendo during conditions in which no exogenous indicator was present. The negative x-intercepts of plots of τ or 1/A vs. κ′exo are equal to 1 + κendo and thus provide two independent measures of κendo. Moreover, the reciprocal of the slope of the plot of τ vs. κ′exo provides γ. Because the added buffer approach requires that Ca2+ influx remains stable across trials in individual cells, we excluded cells in which there was a substantial change in Ca2+ influx, measured as either the product of the amplitude and the decay time constants (A*τ) or the charge of the leak-subtracted Ca2+ currents, over the course of the recording. Additionally, we excluded data points from later timepoints in individual recordings when there was a sharp change in Ca2+ influx, likely due to phototoxicity from repeated laser illumination. In these cases, we were able to analyze points from earlier in the recording. These various layers of quality control meant that we typically performed linear fits to measure κendo using four or five data points per cell.

Unless otherwise noted, data were compared using an unpaired Student’s t-test and differences were considered significant with p < 0.05. As indicated below, we used a Pearson correlation to test for linear dependence between measures of Ca2+ influx and recording time.

Results

Rod and cone photoreceptors in vertical slices of tiger salamander retinas were loaded with Ca2+-sensitive and Ca2+-insensitive fluorescent dyes (Fluo5F and Alexa568, respectively) through the patch pipette during whole-cell voltage clamp recordings. We measured the time course of dye loading by monitoring the increase of FAlexa - the fluorescence intensity of Alexa568 - at rod and cone synaptic terminals.

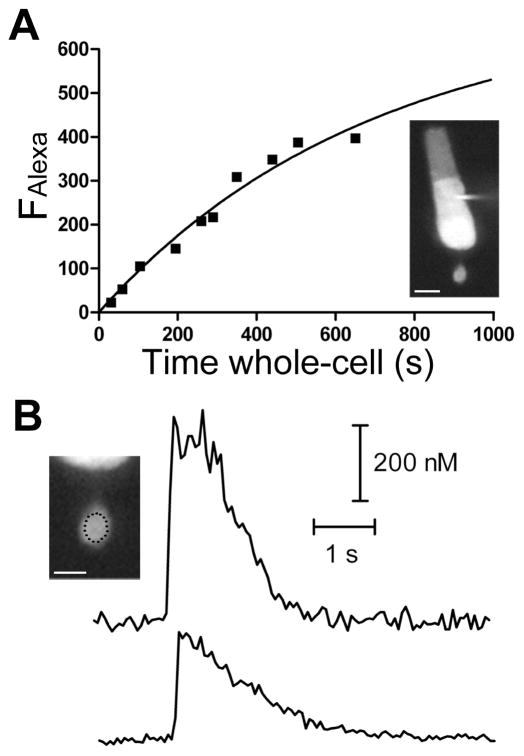

In the synaptic terminals of rods, FAlexa increased with an average time constant of 745 ± 190 s (range: 297–2904 s; n = 14 rods). An example from a single cell is shown in Figure 1A. To measure depolarization-induced changes in intracellular [Ca2+], rods were stimulated with a 75 ms step to −25 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV (Figure 1B). This stimulus was chosen to limit the increase in intracellular [Ca2+] to influx from voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by minimizing contributions from CICR (Cadetti et al., 2006). Responses evoked by longer and more strongly depolarizing stimuli (i.e., 125 ms step to −10 mV) had an initial fast rise, that was followed by a slower second phase of increasing [Ca2+] before reaching a plateau for several seconds, after which the signal declined toward baseline (not shown). Previous work has shown that this secondary increase is due to CICR (Cadetti et al., 2006). In contrast, as shown by the example in Fig. 1B, a shorter 75 ms step to −25 mV triggered only a quick rise in intracellular [Ca2+]Free that decayed rapidly back to baseline. The region of interest in which fluorescence measurements were made is illustrated in the inset in Fig. 1B. The depolarization-evoked Ca2+ increase was confined to the synaptic terminal in rods. The subsequent decay could be fit with a monoexponential function. As the fluorescent dye from the pipette solution gradually diffused into rod terminals, the amplitude of the Ca2+ transients decreased and the time course of recovery slowed, as expected from an increased Ca2+ binding ratio of the Fluo5F indicator (κ′exo) ratio due to an increase in [Fluo5F] in the terminal.

Figure 1. Dye loading and stimulus-evoked transients in rod terminals.

A) Increase in FAlexa, the fluorescence of the Ca2+-insensitive dye Alexa568 (100 μM in the patch pipette), in a representative rod terminal over the duration of a whole-cell recording could be fit with a single exponential function with τ = 688 s. Inset, Alexa568 fill of the whole rod photoreceptor near the end of the recording. B) Ca2+ transients triggered by a 75 ms step to −25 mV measured with the Ca2+-sensitive dye Fluo5F (200 μM in the patch pipette) at two different time points in the recording. The top trace was recorded 147 s after the beginning the recording, when κ′exo = 21. The Ca2+ transient had a peak amplitude of 0.56 μM and declined toward baseline with τ = 0.58 s. The bottom trace was recorded 475 s after breaking in, when κ′exo = 67. The amplitude was 0.29 μM and recovery τ was 1.1 s. Inset, the region of the terminal from which fluorescent measurements were taken is marked with the dotted line. Scale bar: A) 10 μm, B) 5 μm.

We analyzed both the amplitude and kinetics of the transients to measure the endogenous Ca2+ binding ratio (κendo) in rod terminals (Figure 2). This was accomplished by linear regression of the reciprocal of the free Ca2+ transient amplitudes (1/A) plotted as a function of κ′exo (Equation 2). Figure 2A shows an example of such data plotted from a single cell. κ′exo increased as [Fluo5F] increased during the course of the whole-cell recording. The x-intercept of the regression line, at 1/A = 0, provides a measurement of κendo, which averaged 25.8 ± 6.0 (n = 14 rods). Similarly, when the time constant of the free Ca2+ transient decay was plotted against κ′exo, linear extrapolation to the x-intercept gave a prediction for κendo of 28.2 ± 3.7 (n = 14 rods; Figure 2B). Using the slope of this regression, we calculated the extrusion rate constant (γ) of 96 ± 12 s−1 (n = 14 rods). Using different values for [Ca2+]rest other than the measured 77 nM had only modest effects on the measured values of κendo; if [Ca2+]rest was assumed to be 10 nM, then κendo was 29.5 ± 6.8 and if it was assumed to be 200 nM, κendo was 20.5 ± 4.8. These results indicate that approximately 1 of every 25 Ca2+ ions entering the rod terminal following depolarization contributes to free Ca2+.

Figure 2. Change in amplitude and decay kinetics of rod Ca2+ transients during dialysis of Fluo5F.

A) The reciprocal of the Ca2+ transient amplitude plotted against exogenous buffering ratio of the Ca2+-sensitive dye, Fluo5F, obtained from a recording of the representative rod in shown Fig 1. As κ′exo increased due to increasing [Fluo5F], the amplitude of the Ca2+ transients decreased. Extrapolation to the x-intercept with a fit line provides the endogenous Ca2+ binding ratio, κendo, which was 23 for this rod. B) Time constant of the decay of the Ca2+ transient (τ) plotted against κ′exo. As κ′exo increased, τ slowed. Linear extrapolation to the x-intercept gives κendo = 22 for this rod, similar to the measurement derived from the amplitude. The reciprocal slope of this fit line is the extrusion rate constant (γ), which was 83 s−1 for this cell. C) Total Ca2+ influx, measured as the product of the Ca2+ transient amplitude and the time constant of decay (A* τ) for the responses of all rods did not significantly depend on recording duration (p > 0.05, Pearson correlation). D) The charge of leak-subtracted Ca2+ currents (QCa) also did not significantly depend on recording duration (p > 0.05, Pearson correlation).

The added buffer approach requires that Ca2+ influx remains stable as buffering is altered by the addition of a Ca2+ indicator dye since changes in Ca2+ influx would introduce errors in the measurements of endogenous Ca2+ buffering. Therefore, for each experiment, we verified that Ca2+ influx did not change over the course of the recording. To do this, we tested for each cell whether A*τ depended on κ′exo and excluded data in which A*τ changed notably over the course of a recording. Additionally, in a subset of experiments, we measured the charge transfer of leak-subtracted Ca2+ currents (QCa). These occasionally ran down after >10 minutes of whole-cell recording and repeated imaging. This was reflected in individual cells as a decline in A*τ and/or a sudden reduction in QCa and was likely the result of phototoxicity from repeated laser illumination. For the population of data included in our analysis of rods, neither A*τ (Figure 2C) nor QCa (Figure 2D) was significantly correlated with recording time (p > 0.05, Pearson correlation).

We performed similar experiments in cones (Figure 3). The time constant of dye loading in cone terminals was 345 ± 65 s (range: 179–830 s, n = 10 cones), which was somewhat faster than in rods, although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.06). The slower dye loading in rods may be because the thin rod axon slows the diffusion of dye to the terminal. As shown by the location of the region of interest in the inset in Fig. 3B, the cone terminal rests at the base of the cone soma. There is little or no contribution of CICR to intraterminal Ca2+ changes in cones (Cadetti et al., 2006), so we used a longer (125 ms) and more strongly depolarizing step (to −10 mV from −70 mV) to trigger Ca2+ entry. Similar to rods, this depolarization triggered a transient increase in [Ca2+]Free that declined back to baseline with a monoexponential time course (Figure 3B). Extrapolation of a linear fit of the reciprocal of the amplitude against κ′exo to the negative x-intercept provided κendo of 51.7 ± 14.7 (n = 10 cones). We obtained a similar value with a fit of τ plotted against κ′exo. Measured in this way, κendo was 48.2 ± 12.0 (n = 10 cones). Figures 3A and 3B show examples of data plotted from a single cell. As in rods, using different values for [Ca2+]rest had only modest effects on κendo. At [Ca2+]rest of 10 nM κendo = 53.6 ± 16.4 and κendo = 44.0 ± 13.5 when [Ca2+]rest was assumed to be 200 nM. The values of κendo indicate that approximately 1 of every 50 Ca2+ ions entering the cone terminal contributes to [Ca2+]Free. While these measurements of κendo were slightly higher than for rods, they did not differ significantly between rods and cones (p > 0.05). Using the reciprocal slope of the regression lines fitted to τ plotted against κ′exo, we measured γ of 157 ± 30 s−1 in cones. Again, this value is larger than that measured for rods, but it was not significantly different between the two cell types (p > 0.05).

Figure 3. Dye loading and stimulus-evoked transients in cone terminals.

A) Fluorescence of the Ca2+-insensitive dye, Alexa568, gradually increased in a representative cone terminal following establishment of whole-cell recording configuration. From a fit with a single exponential function, the time constant of dye diffusion to the terminal for this cone was 830 s. Inset, flattened z-stack of FAlexa images of the cone near the end of the recording. B) Ca2+ transients, measured with the fluorescence signal of the Ca2+-sensitive dye Fluo5F, evoked in the cone in response to step depolarization (125 ms, to −10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV). The top trace was recorded 80 s after establishing whole-cell recording configuration, when κ′exo = 8.1. The Ca2+ transient amplitude was 1.0 μM and it decayed with τ = 0.38 s. The lower trace was recorded 282 s after establishing the whole-cell recording, when κ′exo = 31 and had an amplitude of 0.71 μM and τ = 0.51 s. Inset, the region of the terminal from which fluorescent measurements were taken is marked with the dotted line. Scale bar: A) 10 μm, B) 5 μm.

As with rods, we measured the dependence of A*τ on κ′exo to ensure that Ca2+ influx remained stable throughout the course of a recording and excluded cells that exhibited a notable change. In a subset of cells, we also recorded leak-subtracted Ca2+ currents to assess the dependence of QCa on recording time. For the population of data used to measure endogenous buffering properties, neither A*τ (Figure 4C) nor QCa (Figure 4D) were significantly correlated with recording time (p > 0.05, Pearson correlation). In some cases, although A*τ showed a clear decline late in the recording we were able to measure κendo based on a fit of data points from earlier in the recording.

Figure 4. Change in amplitude and decay kinetics of cone Ca2+ transients during dialysis of Fluo5F.

A) The reciprocal of the Ca2+ transient amplitude was plotted against κ′exo, which increased as the cone was dialyzed Fluo5F over the course of the recording. As κ′exo increased, the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient decreased. Extrapolation to the x-intercept yielded a value of κendo = 38 for this cone. Data are from the same cone shown in Fig. 1. B) A similar analysis was performed with the time constant (τ) of Ca2+ transient decay, which slowed with increasing κ′exo. The x-intercept of a linear fit yielded κendo = 49. The reciprocal slope of this line gave a value for the extrusion rate constant (γ) for this cone of 159 s−1. C) Ca2+ influx over the course of all cone recordings was measured as the product of the Ca2+ transient and time constant of decay (A * τ). Linear regression showed that that this did not significantly depend on recording duration (p > 0.05, Pearson correlation). D) Ca2+ charge transfer (QCa) was measured from leak-subtracted Ca2+ currents for a subset of the recordings. QCa did not significantly depend on recording time (P > 0.05, Pearson correlation).

In cones, unlike rods, we were also able to record stimulus-evoked Ca2+ signals in somas, which are immediately adjacent to the synaptic terminals in salamander cones (Fig. 5). Similar to Ca2+ responses in cone terminals, somatic Ca2+ transients decreased in amplitude and decayed progressively more slowly with increasing κ′exo. Using the reciprocal of the amplitude of the Ca2+ transients, we measured κendo of 43.8 ± 10.7 (n = 14 cones). Likewise, κendo measured from τ of the Ca2+ transient decay was 49.1 ± 19.1 (n = 14 cones). These values were not significantly different from measurements in cone terminals (p > 0.05). Representative data from a single cone soma are illustrated in Figure 5C and D. The reciprocal slope of the regression line fitted to the plot of τ against κ′exo yielded a significantly smaller value for the extrusion rate constant, γ (37.3 ± 5.1 s−1, p = 0.003), in somas than in terminals.

Figure 5. Stimulus-evoked Ca2+ signals in cone somas.

A) Ca2+ signal recorded in the soma of a representative cone in response to a 125 ms depolarization to −10 mV from a holding potential of −70 mV, 87 s after rupture of the patch, when κ′exo = 72. The amplitude attained 184 nM and the time constant of recovery was 2.11 s. Inset, the region from which fluorescent measurements were taken is marked with the dotted line. B) Ca2+ signal recorded from the same cone soma when κ′exo = 156, 330 s after breaking in. The amplitude of the Ca2+ transient was 104 nM and the time constant was 3.59 s. C) The reciprocal of the Ca2+ transient amplitude was plotted against κ′exo, which increased as this cone was dialyzed Fluo5F over the course of the recording. As κ′exo increased, the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient decreased. Extrapolation to the x-intercept yielded a value of κendo = 52 for this cone. D) A similar analysis was performed with the time constant (τ) of Ca2+ transient decay, which slowed with increasing κ′exo. The x-intercept of a linear fit yielded κendo = 47. The reciprocal slope of this line gave a value for the extrusion rate constant (γ) for this cone of 60 s−1. Scale bar: A) 10 μm.

Discussion

We used the added buffer approach to quantitatively study the features of Ca2+-handling in synaptic terminals of rod and cone photoreceptors in salamander retina. The principal finding of our study is that the Ca2+ binding ratio (κendo) is fairly similar in rods and cones - ~25 for rods and ~50 for cones, meaning that only ~2–4% of Ca2+ ions that enter the terminal contribute to the free Ca2+. Additionally, this indicates that endogenous buffering capacity can be mimicked by including 50–100 μM EGTA or BAPTA, which have similar Kd values (Naraghi, 1997), in the intracellular patch pipette solutions during whole-cell recordings from rods and cones.

Comparison of these findings with previous descriptions of Ca2+ handling by retinal bipolar cells - second-order retinal neurons that also signal with synaptic ribbons - shows both similarities and differences with photoreceptors. As in photoreceptors, restoration of [Ca2+]rest after depolarization-evoked Ca2+ influx in bipolar cells is mediated principally by a plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA), likely the PMCA2 subtype (Morgans et al., 1998; Krizaj et al., 2002; Duncan et al., 2006; Wan et al., 2012). Measurements of the kinetics of Ca2+ transients in bipolar cells suggests that they decay more slowly than in photoreceptors, with a time constant of ~1.6 s (Wan et al., 2008, 2012), although there is a faster component with a time constant of ~150 ms (Wan et al., 2008) that more closely resembles the time constant we measured in photoreceptor terminals.

Values for κendo appear to differ considerably between photoreceptors and bipolar cells. In goldfish Mb1 bipolar cells, κendo is ~470 (Burrone et al., 2002). This is consistent with recordings using both perforated patch, to preserve the intracellular milieu, and dialysis of EGTA or BAPTA, where the endogenous buffering was estimated to be roughly equivalent to 0.5 mM BAPTA or 2 mM EGTA (Burrone et al., 2002; Hull and von Gersdorff, 2004). Similarly, measurements of a delayed component of exocytosis from mouse rod bipolar cells suggest the endogenous buffering is equivalent to 1–2 mM BAPTA or EGTA (Mehta et al., 2014). In auditory hair cells, imaging of ribbon-associated Ca2+ microdomains indicates that endogenous buffering in hair cells is also between 0.5–2 mM EGTA (Frank et al., 2009) while in saccular hair cells, measurements of Ca2+-activated potassium currents suggest that it is similar to 0.5–1.6 mM BAPTA (Roberts, 1993). Thus, the low Ca2+ binding ratio of 25–50 in photoreceptor terminals--equivalent to 50–100 μM EGTA or BAPTA--appears unique among ribbon-type synapses. κendo values in photoreceptors are more similar to those found using the added buffer approach in non-ribbon presynaptic terminals. κendo is 77 in larval Drosophila motor terminals (He and Lnenicka, 2011), 20 in dentate gyrus granule cell terminals (Jackson and Redman, 2003), ~40 at the calyx of Held (Helmchen et al., 1997), and ~140 in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons (Koester and Sakmann, 2000).

There is also a wide range of Ca2+ binding ratios in dendrites and cell bodies. Within the retina, κendo in ganglion cell somata is reported to decline from 575 in early postnatal retinas to ~120 in adult RGCs (Mann et al., 2005). In the dendrites of ganglion cells, however, κendo varies from cell-to-cell, ranging from 2 to 123 (Gartland and Detwiler, 2011). These values are correlated with other parameters of Ca2+ handling such as extrusion rate constant and total Ca2+ influx, suggesting that they work together in a homeostatic fashion to ensure uniform Ca2+ handling in RGC dendrites. κendo is ~50 in spinal motoneuron somata (Palecek et al., 1999), ~100–200 in CA1 pyramidal dendrites (Helmchen et al., 1996; Maravall et al., 2000), ~125 in somata of Layer V pyramidal neurons (Helmchen et al., 1996), and 75 in chromaffin cell somata (Neher and Augustine, 1992). We were able to calculate κendo in cone somas, finding that it was ~45, similar to measurements in the terminals.

Fast Ca2+ buffering is accomplished largely by the endogenous Ca2+ binding proteins calbindin (CB), calretinin (CR), and parvalbumin (PV) (Schwaller et al., 2002; Rusakov, 2006; Schwaller, 2010). In photoreceptors, the distribution of these proteins varies depending on species and photoreceptor subtype. CB tends to be present in photoreceptors of most species, aside from fish, but was only detected in accessory members of double cone pairs in amphibian retinas (Hamano et al., 1990; Deng et al., 2001; Bennis et al., 2005; Zhang and Wu, 2009). PV and CR were absent from amphibian cones (Deng et al., 2001). CB, CR, PV were not detected in mouse rods or cones (Haverkamp and Wässle, 2000), although CR is reportedly present in some mammalian photoreceptors (Bennis et al., 2005). Another Ca2+ binding protein, caldendrin, appears to be absent from mouse rods and cones (Haverkamp and Wässle, 2000).

Other Ca2+ binding molecules may instead account for the endogenous Ca2+ buffering in rods and cones. CaBP4 plays a key role synaptic transmission in both rods and cones by binding to the CaV1.4 Ca2+ channels, where it shifts the Ca2+ current activation into a physiological voltage range (Haeseleer et al., 2004; Maeda et al., 2005). CaBP4 binds to the CaV1.4 channel in both Ca2+-bound and -unbound states (Haeseleer et al., 2004), and is thus well positioned to buffer Ca2+ near the Ca2+ entry sites.

An additional Ca2+ binding protein, recoverin (Rv), is a member of the neuronal calcium sensor (NCS) family and has a well-established role in Ca2+-dependent regulation of phototransduction (Makino et al., 2004). However, in addition to being present in outer segments, Rv is also found in photoreceptor terminals (Haverkamp and Wässle, 2000; Makino et al., 2004; Sampath et al., 2005) and Rv knockout prolongs the light responses of downstream neurons independently of actions on phototransduction, an effect that may be the result of altered Ca2+ buffering in the terminal (Sampath et al., 2005).

Finally, guanylate cyclase activating proteins (GCAPs), which are also members of the NCS family and are important in restoring resting levels of cGMP in photoreceptor outer segments (Baehr and Palczewski, 2009), are found bound to synaptic ribbons in rods and cones, where they appear to play a role in regulating ribbon structure, possibly by buffering Ca2+ in the terminal (Burgoyne, 2007; Schmitz et al., 2012). Their Ca2+ binding properties may be important in maintaining [Ca2+]free in photoreceptors and mutations that affect GCAP Ca2+ sensitivity lead to photoreceptor cell death (Baehr and Palczewski, 2009; Jiang and Baehr, 2010), although this is likely the result of prolonged Ca2+ influx through outer segment cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (Baehr and Palczewski, 2009) and not reduced buffer capacity in the terminal.

In addition to being buffered by endogenous Ca2+ binding proteins, Ca2+ in the synaptic terminal is sequestered into intracellular stores such as the sarco-/endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria or is pumped into the extracellular space via PMCA and/or sodium/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX). This process contributes to the time course of decay of the free Ca2+ transient. In mouse, both PMCA and NCX are present at photoreceptor synaptic terminals (Johnson et al., 2007). However, PMCA appears to play the dominant role in Ca2+ extrusion from the terminal with NCX having a role in the outer segment (Thoreson et al., 1997; Krizaj and Copenhagen, 1998; Morgans et al., 1998; Zenisek and Matthews, 2000). Loss of a functional PMCA protein leads to deficits in rod synaptic transmission (Duncan et al., 2006). Mitochondria are present in photoreceptor terminals in vascularized retinas, but are absent from photoreceptor terminals in the avascular salamander retina (Johnson et al., 2007; Linton et al., 2010). At ribbon synapses of goldfish bipolar cells, mitochondria appear to act principally as an energy source and make little contribution to Ca2+ sequestration (Zenisek and Matthews, 2000). In photoreceptors, the mitochondria are involved in sequestering Ca2+ in the ellipsoid rather than the terminal (Szikra and Krizaj, 2007).

We measured extrusion rate constants (γ) from the slope of the κ′exo vs. τ plots in rods and cones, arriving at values of ~100 s−1 and ~160 s−1, respectively. These values are slower than those reported in other presynaptic terminals; γ was 400–900 s−1 in the calyx of Held (Helmchen et al., 1997), ~2600 s−1 in cortical pyramidal neurons (Koester and Sakmann, 2000), and 800–1600 s−1 in Drosophila motor synapse terminals (He and Lnenicka, 2011). From the data presented in (Jackson and Redman, 2003), we estimate γ of ~500 s−1 in axon terminals of dentate gyrus granule cells. In cones, we found that κendo was similar in somas and terminals, but γ was considerably slower in somas (~ 35 s−1), consistent with a spatial segregation of extrusion mechanisms in different regions of the photoreceptor (Thoreson et al., 1997; Krizaj and Copenhagen, 1998; Morgans et al., 1998; Zenisek and Matthews, 2000; Johnson et al., 2007; Szikra and Krizaj, 2007). Exocytosis in rods and cones terminates with time constants of ~30 ms and 18 ms, respectively (Thoreson, 2007). These values are faster than the measured time constants of Ca2+ extrusion (~300 ms and 265 ms in rods and cones, respectively), suggesting that factors other than extrusion are more important in termination of exocytosis.

Synaptic release in spiking neurons is triggered by action potential-induced gating of P/Q-type, N-type, and/or R-type Ca2+ channels, causing a relatively short-lived rise in intraterminal [Ca2+]. This transient rise in [Ca2+] presumably helps to keep transmitter release tightly synchronized with neuronal spiking. This is in contrast to rod and cone synapses, which encode light responses by tonically altering the rate of glutamate release at the synapse, a process that is accomplished by gating of non-inactivating L-type Ca2+ currents. The lower extrusion rate in rods and cones might facilitate a longer-lasting rise in average intraterminal [Ca2+], which could in turn support sustained release. Interestingly, the high affinity of the exocytotic Ca2+ sensor in photoreceptors, which has a cooperativity of n = 2, is the result of an especially slow off rate (Duncan et al., 2010). The low values of κendo and γ might thus allow [Ca2+] to rise in nanodomains near the presynaptic membrane so as to facilitate binding of a second Ca2+ ion to the sensor before the first leaves. Because nanodomain size is beneath the diffraction limit for visible light, they are impossible resolve with Ca2+ sensitive dyes. Consequently, we cannot directly assess Ca2+ buffering within submembrane nanodomains.

Rods and cones differ considerably in their kinetics of exocytosis with rods exhibiting much greater amounts of slow release (Schnapf and Copenhagen, 1982; Cadetti et al., 2005; Rabl et al., 2005; Thoreson, 2007). It has been proposed that differences in Ca2+ handling in each cell type might contribute to these differences (Rusakov, 2006; Thoreson, 2007). However, the close similarities of both Ca2+ binding ratio and the extrusion rate constant in rods and cones suggest that these are not major contributors to the rod-cone differences in synaptic transmission. Instead, the additional slow release from rods appears to be due to non-ribbon release of vesicles triggered by liberation of Ca2+ from intracellular stores by CICR (Cadetti et al., 2006; Suryanarayanan and Slaughter, 2006; Babai et al., 2010b; Chen et al., 2014). Slow rates of extrusion might allow [Ca2+] to rise sufficiently in rods to trigger CICR and support sustained synaptic transmission. In cones, while local Ca2+ signals are responsible for high efficiency synaptic transmission at light offset, average intraterminal [Ca2+] supports sustained release by accelerating the resupply of synaptic vesicles to the ribbon (Jackman et al., 2009; Babai et al., 2010a; Bartoletti et al., 2011). Low endogenous Ca2+ buffering and relatively slow extrusion might also support sustained synaptic transmission by cones in darkness.

Acknowledgments

NIH grant EY10542 (WBT). Senior Scientific Investigator Award from Research to Prevent Blindness (WBT). Financial support from Fight for Sight is gratefully acknowledged (MJVH).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Babai N, Bartoletti TM, Thoreson WB. Calcium regulates vesicle replenishment at the cone ribbon synapse. J Neurosci. 2010a;30:15866–15877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2891-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babai N, Morgans CW, Thoreson WB. Calcium-induced calcium release contributes to synaptic release from mouse rod photoreceptors. Neuroscience. 2010b;165:1447–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader CR, Bertrand D, Schwartz EA. Voltage-activated and calcium-activated currents studied in solitary rod inner segments from the salamander retina. J Physiol. 1982;331:253–284. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baehr W, Palczewski K. Focus on molecules: guanylate cyclase-activating proteins (GCAPs) Exp Eye Res. 2009;89:2–3. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Hille B. Ionic channels of the inner segment of tiger salamander cone photoreceptors. J Gen Physiol. 1989;94:719–743. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.4.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoletti TM, Jackman SL, Babai N, Mercer AJ, Kramer RH, Thoreson WB. Release from the cone ribbon synapse under bright light conditions can be controlled by the opening of only a few Ca2+ channels. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:2922–2935. doi: 10.1152/jn.00634.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennis M, Versaux-Botteri C, Repérant J, Armengol JA. Calbindin, calretinin and parvalbumin immunoreactivity in the retina of the chameleon (Chamaeleo chamaeleon) Brain Behav Evol. 2005;65:177–187. doi: 10.1159/000083683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD. Neuronal calcium sensor proteins: generating diversity in neuronal Ca2+ signaling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:182–193. doi: 10.1038/nrn2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrone J, Neves G, Gomis A, Cooke A, Lagnado L. Endogenous calcium buffers regulate fast exocytosis in the synaptic terminal of retinal bipolar cells. Neuron. 2002;33:101–112. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00565-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadetti L, Bryson EJ, Ciccone CA, Rabl K, Thoreson WB. Calcium-induced calcium release in rod photoreceptor terminals boosts synaptic transmission during maintained depolarization. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:2983–2990. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04845.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadetti L, Tranchina D, Thoreson WB. A comparison of release kinetics and glutamate receptor properties in shaping rod-cone differences in EPSC kinetics in the salamander retina. J Physiol. 2005;569:773–788. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.096545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Križaj D, Thoreson WB. Intracellular calcium stores drive slow non-ribbon vesicle release from rod photoreceptors. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:20. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S-Y, Jackman S, Thoreson WB, Kramer RH. Light regulation of Ca2+ in the cone photoreceptor synaptic terminal. Vis Neurosci. 2008;25:693–700. doi: 10.1017/s0952523808080814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey DP, Dubinsky JM, Schwartz EA. The calcium current in inner segments of rods from the salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) retina. J Physiol. 1984;354:557–575. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cork KM, Thoreson WB. Rapid kinetics of endocytosis at rod photoreceptor synapses depends upon endocytic load and calcium. Vis Neurosci. 2014;31:227–235. doi: 10.1017/S095252381400011X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng P, Cuenca N, Doerr T, Pow DV, Miller R, Kolb H. Localization of neurotransmitters and calcium binding proteins to neurons of salamander and mudpuppy retinas. Vision Res. 2001;41:1771–1783. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G, Rabl K, Gemp I, Heidelberger R, Thoreson WB. Quantitative analysis of synaptic release at the photoreceptor synapse. Biophys J. 2010;98:2102–2110. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JL, Yang H, Doan T, Silverstein RS, Murphy GJ, Nune G, Liu X, Copenhagen D, Tempel BL, Rieke F, Krizaj D. Scotopic visual signaling in the mouse retina is modulated by high-affinity plasma membrane calcium extrusion. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7201–7211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5230-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank T, Khimich D, Neef A, Moser T. Mechanisms contributing to synaptic Ca2+ signals and their heterogeneity in hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4483–4488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813213106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartland AJ, Detwiler PB. Correlated variations in the parameters that regulate dendritic calcium signaling in mouse retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2011;31:18353–18363. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4212-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeseleer F, Imanishi Y, Maeda T, Possin DE, Maeda A, Lee A, Rieke F, Palczewski K. Essential role of Ca2+-binding protein 4, a Cav1.4 channel regulator, in photoreceptor synaptic function. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1079–1087. doi: 10.1038/nn1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamano K, Kiyama H, Emson PC, Manabe R, Nakauchi M, Tohyama M. Localization of two calcium binding proteins, calbindin (28 kD) and parvalbumin (12 kD), in the vertebrate retina. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302:417–424. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp S, Wässle H. Immunocytochemical analysis of the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T, Lnenicka GA. Ca2+ buffering at a drosophila larval synaptic terminal. Synap N Y N. 2011;65:687–693. doi: 10.1002/syn.20909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F, Borst JG, Sakmann B. Calcium dynamics associated with a single action potential in a CNS presynaptic terminal. Biophys J. 1997;72:1458–1471. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78792-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F, Imoto K, Sakmann B. Ca2+ buffering and action potential-evoked Ca2+ signaling in dendrites of pyramidal neurons. Biophys J. 1996;70:1069–1081. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79653-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hook MJ, Thoreson WB. Simultaneous whole-cell recordings from photoreceptors and second-order neurons in an amphibian retinal slice preparation. J Vis Exp JoVE. 2013 doi: 10.3791/50007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull C, von Gersdorff H. Fast endocytosis is inhibited by GABA-mediated chloride influx at a presynaptic terminal. Neuron. 2004;44:469–482. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman SL, Choi S-Y, Thoreson WB, Rabl K, Bartoletti TM, Kramer RH. Role of the synaptic ribbon in transmitting the cone light response. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:303–310. doi: 10.1038/nn.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MB, Redman SJ. Calcium dynamics, buffering, and buffer saturation in the boutons of dentate granule-cell axons in the hilus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1612–1621. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01612.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Baehr W. GCAP1 mutations associated with autosomal dominant cone dystrophy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;664:273–282. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1399-9_31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Jr, Perkins GA, Giddabasappa A, Chaney S, Xiao W, White AD, Brown JM, Waggoner J, Ellisman MH, Fox DA. Spatiotemporal regulation of ATP and Ca2+ dynamics in vertebrate rod and cone ribbon synapses. Mol Vis. 2007;13:887–919. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester HJ, Sakmann B. Calcium dynamics associated with action potentials in single nerve terminals of pyramidal cells in layer 2/3 of the young rat neocortex. J Physiol. 2000;529:625–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizaj D, Copenhagen DR. Compartmentalization of calcium extrusion mechanisms in the outer and inner segments of photoreceptors. Neuron. 1998;21:249–256. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80531-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizaj D, Demarco SJ, Johnson J, Strehler EE, Copenhagen DR. Cell-specific expression of plasma membrane calcium ATPase isoforms in retinal neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2002;451:1–21. doi: 10.1002/cne.10281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton JD, Holzhausen LC, Babai N, Song H, Miyagishima KJ, Stearns GW, Lindsay K, Wei J, Chertov AO, Peters TA, Caffe R, Pluk H, Seeliger MW, Tanimoto N, Fong K, Bolton L, Kuok DLT, Sweet IR, Bartoletti TM, Radu RA, Travis GH, Zagotta WN, Townes-Anderson E, Parker E, Van der Zee CEEM, Sampath AP, Sokolov M, Thoreson WB, Hurley JB. Flow of energy in the outer retina in darkness and in light. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8599–8604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002471107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Lem J, Palczewski K, Haeseleer F. A critical role of CaBP4 in the cone synapse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4320–4327. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino CL, Dodd RL, Chen J, Burns ME, Roca A, Simon MI, Baylor DA. Recoverin regulates light-dependent phosphodiesterase activity in retinal rods. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:729–741. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm AT, Kourennyi DE, Barnes S. Protons and calcium alter gating of the hyperpolarization-activated cation current (I(h)) in rod photoreceptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1609:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00687-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann M, Haq W, Zabel T, Guenther E, Zrenner E, Ladewig T. Age-dependent changes in the regulation mechanisms for intracellular calcium ions in ganglion cells of the mouse retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2735–2743. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maravall M, Mainen ZF, Sabatini BL, Svoboda K. Estimating intracellular calcium concentrations and buffering without wavelength ratioing. Biophys J. 2000;78:2655–2667. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76809-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maricq AV, Korenbrot JI. Calcium and calcium-dependent chloride currents generate action potentials in solitary cone photoreceptors. Neuron. 1988;1:503–515. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta B, Ke J-B, Zhang L, Baden AD, Markowitz AL, Nayak S, Briggman KL, Zenisek D, Singer JH. Global Ca2+ signaling drives ribbon-independent synaptic transmission at rod bipolar cell synapses. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2014;34:6233–6244. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5324-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer AJ, Rabl K, Riccardi GE, Brecha NC, Stella SL, Jr, Thoreson WB. Location of release sites and calcium-activated chloride channels relative to calcium channels at the photoreceptor ribbon synapse. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:321–335. doi: 10.1152/jn.00332.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgans CW, Bayley PR, Oesch NW, Ren G, Akileswaran L, Taylor WR. Photoreceptor calcium channels: insight from night blindness. Vis Neurosci. 2005;22:561–568. doi: 10.1017/S0952523805225038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgans CW, El Far O, Berntson A, Wässle H, Taylor WR. Calcium extrusion from mammalian photoreceptor terminals. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2467–2474. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02467.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naraghi M. T-jump study of calcium binding kinetics of calcium chelators. Cell Calcium. 1997;22:255–268. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Augustine GJ. Calcium gradients and buffers in bovine chromaffin cells. J Physiol. 1992;450:273–301. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palecek J, Lips MB, Keller BU. Calcium dynamics and buffering in motoneurones of the mouse spinal cord. J Physiol. 1999;520:485–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabl K, Cadetti L, Thoreson WB. Kinetics of exocytosis is faster in cones than in rods. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4633–4640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4298-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WM. Spatial calcium buffering in saccular hair cells. Nature. 1993;363:74–76. doi: 10.1038/363074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusakov DA. Ca2+-dependent mechanisms of presynaptic control at central synapses. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:317–326. doi: 10.1177/1073858405284672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampath AP, Strissel KJ, Elias R, Arshavsky VY, McGinnis JF, Chen J, Kawamura S, Rieke F, Hurley JB. Recoverin improves rod-mediated vision by enhancing signal transmission in the mouse retina. Neuron. 2005;46:413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz F, Natarajan S, Venkatesan JK, Wahl S, Schwarz K, Grabner CP. EF hand-mediated Ca- and cGMP-signaling in photoreceptor synaptic terminals. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:26. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnapf JL, Copenhagen DR. Differences in the kinetics of rod and cone synaptic transmission. Nature. 1982;296:862–864. doi: 10.1038/296862a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaller B, Meyer M, Schiffmann S. “New” functions for “old” proteins: the role of the calcium-binding proteins calbindin D-28k, calretinin and parvalbumin, in cerebellar physiology. Studies with knockout mice. Cerebellum Lond Engl. 2002;1:241–258. doi: 10.1080/147342202320883551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaller B. Cytosolic Ca2+ buffers. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a004051. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele EC, Jr, Chen X, Iuvone PM, MacLeish PR. Imaging of Ca2+ dynamics within the presynaptic terminals of salamander rod photoreceptors. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:4544–4553. doi: 10.1152/jn.01193.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryanarayanan A, Slaughter MM. Synaptic transmission mediated by internal calcium stores in rod photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1759–1766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3895-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szikra T, Krizaj D. Intracellular organelles and calcium homeostasis in rods and cones. Vis Neurosci. 2007;24:733–743. doi: 10.1017/S0952523807070587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreson WB, Nitzan R, Miller RF. Reducing extracellular Cl− suppresses dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ currents and synaptic transmission in amphibian photoreceptors. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:2175–2190. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.4.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreson WB, Rabl K, Townes-Anderson E, Heidelberger R. A highly Ca2+-sensitive pool of vesicles contributes to linearity at the rod photoreceptor ribbon synapse. Neuron. 2004;42:595–605. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00254-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreson WB, Stella SL, Jr, Bryson EI, Clements J, Witkovsky P. D2-like dopamine receptors promote interactions between calcium and chloride channels that diminish rod synaptic transfer in the salamander retina. Vis Neurosci. 2002;19:235–247. doi: 10.1017/s0952523802192017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreson WB. Kinetics of synaptic transmission at ribbon synapses of rods and cones. Mol Neurobiol. 2007;36:205–223. doi: 10.1007/s12035-007-0019-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Q-F, Nixon E, Heidelberger R. Regulation of presynaptic calcium in a mammalian synaptic terminal. J Neurophysiol. 2012;108:3059–3067. doi: 10.1152/jn.00213.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Q-F, Vila A, Zhou Z-Y, Heidelberger R. Synaptic vesicle dynamics in mouse rod bipolar cells. Vis Neurosci. 2008;25:523–533. doi: 10.1017/S0952523808080711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson MF, Barnes S. The dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel subtype in cone photoreceptors. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:621–630. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.5.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenisek D, Matthews G. The role of mitochondria in presynaptic calcium handling at a ribbon synapse. Neuron. 2000;25:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80885-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Wu SM. Immunocytochemical analysis of photoreceptors in the tiger salamander retina. Vision Res. 2009;49:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]