Abstract

The three-dimensional structure of Nudaurelia capensis β virus (NβV) was reconstructed to 3.2-nm resolution from images of frozen-hydrated virions. The distinctly icosahedral capsid (~40-nm diameter) contains 240 copies of a single 61-kDa protein subunit arranged with T = 4 lattice symmetry. The outer surface of unstained virions compares remarkably well with that previously observed in negatively stained specimens. Inspection of the density map, volume estimates, and model building experiments indicate that each subunit consists of two distinct domains. The large domain (~40 kDa) has a cylindrical shape, ~4-nm diameter by ~4-nm high, and associates with two large domains of neighboring subunits to form a Y-shaped trimeric aggregate in the outer capsid surface. Four trimers make up each of the 20 planar faces of the capsid. Small domains (~21 kDa) presumably associate at lower radii (~13–16.5 nm) to form a contiguous, nonspherical shell, A T = 4 model, constructed from 80 trimers of the common β-barrel core motif (~20 kDa) found in many of the smaller T = 3 and pseudo T = 3 viruses, fits the dimensions and features seen in the NβV reconstruction, suggesting that the contiguous shell of NβV may be formed by intersubunit contacts between small domains having that motif. The small (~1800 kDa), ssRNA genome is loosely packed inside the capsid with a low average density.

INTRODUCTION

Insects are readily infected with a variety of single-stranded RNA (ssRNA)2 viruses. Some of these viruses are well characterized and have been assigned to specific families including (a) the Nodaviridae, which has been extensively studied by biochemical (Friesen et al., 1980; Gallagher and Rueckert, 1988) and structural methods (Dasgupta et al., 1984; Hosur et al., 1987), (b) the Picornaviridae, which include viruses similar to those that infect mammals (Reavy and Moore, 1983), and (c) the Tetraviridae, whose members have capsids with T = 4 quasi symmetry (Finch et al., 1974). Sixteen viruses are classified or tentatively classified as members of the Tetraviridae because they have capsids and protein subunits of similar size (Hendry et al., 1985). The virions are generally believed not to contain any other proteins. Some members of the family exhibit serological cross-reactivity with anti-Nudaurelia capensis β virus serum (Reinganum et al., 1978; Greenwood and Moore, 1981a,b; Moore et al., 1981, 1985; Hendry et al., 1985). The physical properties of representative members of the family are summarized in Table I.

TABLE I.

Chemical and Physical Properties of Selected Members of the Tetraviridaea

| Virus | Diameter (nm) |

Density (g/ml) |

Sedimentation coefficient (S) |

Capsid protein Mr (kDa) |

RNAMr (kDa) |

∊260/280b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nudaurelia capensis β | 39.7C | 1.295d | 210 | 61d | 1800 | 1.45e |

| Nudaurelia capensis ∊ | 40.1f | 1.28f | 217e | —g | — | — |

| Nudaurelia capensis ω | 40d | 1.285d | — | 65d | — | — |

| Antheraea eucalypti | 32 | — | 215 | — | — | — |

| Trichoplusia ni | 35–38 | 1.3 | 200 | 67–68 | 1900 | — |

| Darna trima | 35–38 | 1.289 | 199 | 62–66 | — | 1.44e |

| Thosea asigna | 35 | 1.275 | 194 | 60.8 | — | 1.32e |

| Philosamia cynthia × ricini | 35 | 1.275 | 206 | 62.4 | — | 1.36e |

| Dasychira pudibunda | 38 | 1.31 | — | 66 | 1800 | 1.43h |

| Pseudoplusia includens | 40 | 1.33 | 190 | 55 | 1900 | 1.42i |

Values from Table III, Moore et al., 1985, unless otherwise noted.

∊260/280 is the spectral absorbance at 260 nm divided by the spectral absorbance at 280 nm.

This paper.

Value not determined.

N. capensis β virus (NβV) is one of at least six viruses that infect the South African pine emperor moth, Nudaurelia (Imbrasia) cytherea capensis (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) (Juckes, 1970; Hendry et al., 1985). The virus replicates in the cytoplasm of gut cells during the moth’s larval stages. The larvae exhibit symptoms that vary from growth retardation to rapid death accompanied by muscular flaccidity and internal liquefaction (Moore et al., 1985). The natural mechanism of virus spread is unknown. Infection possibly occurs when moths produce or lay eggs, since larvae that are apparently infected with latent virus develop symptoms under conditions of feeding stress or overcrowding (Hendry, unpublished results). Attempts to successfully introduce this virus into continuous tissue culture cells have failed (Hendry et al., 1981; Moore et al., 1985), although primary N. cytherea and silkworm (Bombyx mori) cultures appear to support replication, and virus can be propagated in cells after fresh virus is injected into the hemocoel of symptomless N. cytherea larvae (Tripconey, 1970).

The capsid of NβV has a distinct icosahedral shape and contains 240 copies of a single 61-kDa polypeptide that are arranged with T = 4 symmetry (Finch et al., 1974; Hendry et al., 1985). The amino acid compositions of the capsid proteins of three members of the Tetraviridae (Trichoplusia ni virus, NβV, and Darna trima virus) were found to be distinctly different (Moore et al., 1981). A three-dimensional reconstruction of NβV, computed from images of negatively stained specimens, revealed that each triangular face of the icosahedral capsid is composed of 12 protein subunits clustered in four, Y-shaped, trimeric aggregates (Finch et al., 1974). The subunits are packed such that each face is nearly planar and is separated from neighboring faces by deep grooves. The protein shell encapsidates a genome composed of a single molecule of ssRNA (~1800-kDa) (Struthers and Hendry, 1974) that is not polyadenylated (Hendry et al., 1981). The ssRNA serves as a messenger in cell-free translation systems (King et al., 1984; Reavy and Moore, 1984; Hendry, unpublished results).

We have used cryoelectron microscopy and three-dimensional image reconstruction procedures to examine the frozen-hydrated structure of NβV at 3.2-nm resolution (Olson et al., 1987). Images of vitrified samples reveal structural information about the distribution of density throughout the entire virion, not just those features accessible to stains, as is common for negatively stained specimens. In addition, vitrification is known to help preserve the native morphology of biological macromolecules (Adrian et al., 1984; Milligan et al., 1984; Chiu, 1986; Stewart and Vigers, 1986; Dubochet et al., 1988; Olson and Baker, 1989). NβV is apparently the only virus whose capsid structure is solely organized with T = 4 symmetry that has been reconstructed from cryoelectron micrographs. Sindbis virus (Fuller, 1987) and Semliki Forest virus (Vogel et al., 1986) both have trimeric, glycoproteinaceous spikes that project through a lipid bilayer and are arranged on a T = 4 lattice. The reconstruction of sindbis virus also revealed the attachment of the spikes to an inner nucleocapsid that was arranged with T = 3 icosahedral symmetry. Herpes simplex virus has a dominant, T = 16 outer capsid (~125-nm diameter) that supposedly surrounds a T = 4 intermediate layer (~42.5-nm diameter) (Schrag et al., 1989).

This report provides a detailed description of our cryoelectron microscopy and three-dimensional reconstruction studies of the native structure of NβV (Olson et al., 1987). We also compare the structure of NβV in the frozen-hydrated state to that observed in negatively stained samples (Finch et al., 1974). Examination of the NβV capsid structure indicates that intersubunit associations in the contiguous region of the T = 4, quasiequivalent shell may be quite similar to those present in some of the smaller, T = 3 RNA viruses whose structures are known to high resolution (Harrison et al., 1978; Abad-Zapatero et al., 1980; Hogle et al., 1986; Hosur et al., 1987; Rossmann and Johnson, 1989). Recently, single crystals of NβV that diffract to 0.26-nm resolution were grown (Sehnke et al., 1988). Preliminary results indicate that the reconstruction of unstained NβV may provide a suitable starting model for phasing x-ray crystallographic data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus Purification and Electron Microscopy

Moribund N. cytherea larvae were collected from a heavily infested plantation of Pinus radiata and stored at − 20°C. The presence of NβV was confirmed by immunodiffusion (Van Regenmortel, 1982). Virus was extracted from thawed larvae (Morris et al., 1979) and was purified by sucrose density-gradient centrifugation. Isopycnic density-gradient centrifugation (Hendry et al., 1985) and electrophoretic examination of the viral protein (Laemmli, 1970) showed that purified preparations did not contain coinfecting virus particles.

Virus samples were prepared and examined with established cryoelectron microscopy procedures (Adrian et al., 1984; Milligan et al., 1984; Olson and Baker, 1989). A 2.5-µl droplet of a 1–2 mg/ml aqueous virus suspension was applied to 400 mesh copper electron microscope grids coated with perforated carbon films made hydrophilic by glow discharge in air. Excess sample was blotted off with filter paper before plunging the grid into liquid ethane slush. The grid was transferred into liquid nitrogen and then into a specimen cold holder (Gatan Inc., Warrendale, PA) maintained at −165°C. The sample was viewed in a Philips EM420 transmission electron microscope (Philips Electronics Instruments, Mahwah, NJ) and micrographs were recorded at a nominal magnification of 49 000 × at an electron dose of <2000 e−/nm2. Polyoma virus was mixed with the vitrified NβV sample to serve as an internal magnification standard (Olson and Baker, 1989) for measuring the mean particle diameter and intraparticle dimensions of NβV.

NβV specimens, stained with an unbuffered 1% aqueous solution of uranyl acetate, were prepared by conventional adhesion methods on glow-discharged, unperforated carbon support films (Hayat, 1989). The mean diameter of the stained virions was measured directly from the micrographs.

Image Analysis

The micrograph selected for digital processing exhibited minimal astigmatism and drift as detected by eye and was recorded ~1.5 µm underfocus (determined from spacings of the Thon rings in a computed Fourier transform of a small region of the carbon film). The micrograph was digitized at 25-µm intervals (corresponding to ~0.50-nm sampling at the specimen) and was processed on a VAX/VMS 8550 minicomputer (Digital Equipment Corporation, Maynard, MA) with programs written in FORTRAN (Fuller, 1987; Baker et al., 1988, 1989).

Images of individual virions were masked from their surroundings and floated in a uniform background. An initial estimate for the position of each particle center was determined by cross-correlation procedures (Olson and Baker, 1989). The view orientation (θ, φ, ω; Klug and Finch, 1968) for each particle was calculated by use of a modified version (Fuller, 1987; Baker et al., 1988) of the original common lines procedure (Crowther et al., 1970). To reduce the effects of noise arising from features not correlated with icosahedral symmetry, calculations were performed with Fourier transform data only within a (l/16.4)nm−1 (1/3.5)nm−1 range of spatial frequencies.

Translation (particle center) and orientation (view direction) parameters were refined in alternate cycles until negligible improvement was obtained. Interparticle refinement of orientation was typically initiated with a limited set of partially refined data (~5 particles) with a cross-common lines procedure (Fuller, 1987). The number of images included in the data set was slowly expanded as the refinement progressed. Those images that appeared to be inconsistent with the other images on the basis of the common lines phase residuals (Crowther, 1971) were removed from the data set and were subsequently added back and refined at a later stage or were left out completely.

A data set, consisting of 25 unique views of virions with the best preserved icosahedral symmetry, was selected from a total of 46 digitized images. These were combined by use of Fourier-Bessel techniques (Crowther, 1971) to compute a three-dimensional reconstruction. No compensation was made to correct for the nonlinear phase contrast transfer function of the electron microscope (Lepault and Pitt, 1984; Lepault and Leonard, 1985). The resultant electron density map was projected in the same viewing geometry as each of the unprocessed images to visually assess the reliability of the reconstruction procedure (e.g., Baker et al., 1989) and to more accurately refine the particle centers (Baker et al., 1990). These centers were then used to refine the view orientation for each particle a final time before the electron density map was computed.

We quantitatively assessed the reliability and resolution limit of the reconstruction by randomly splitting the 25-particle data set into two groups and calculating independent reconstructions after each of the “half-data” sets was separately refined. Crystallographic R-factors (Blundell and Johnson, 1976) were computed to assess the similarities of the two reconstructions as a function of resolution (Baker et al., 1990). The R-factor at 3.2-nm resolution was 37%. At higher resolutions it exceeded 60%. Thus, the final electron density map was computed from the full data set to 3.2-nm resolution and was symmetry-averaged to impose 532 (icosahedral)-point group symmetry (Fuller, 1987). Large density fluctuations at radii <2.5 nm in the map were attenuated for cosmetic reasons only to reduce the dominant noise artifacts that typically accumulate at the center of three-dimensional reconstructions computed with Fourier–Bessel procedures from data sets of limited size and from images recorded at significant levels of defocus (Toyoshima, 1990).

We computed a radial density plot by azimuthally averaging the three-dimensional map in spherical annuli of ~0.25-nm width. To measure solvent excluded volumes in the reconstruction, a threshold density value was chosen that corresponded approximately to the level at which the contrast between the solvent and the outer capsid surface was highest. This cutoff density was equal to or lower than any spherically averaged density inside the virion. Thus, assuming that the correct magnification is known, the actual volumes must be greater than or equal to the measured values. Volumes were measured within spherical annuli between radii of 0–8, 8–13, and 13–21.3 nm. The largest source of error in the volume estimates and in the relative weights of features in the three-dimensional map is likely to arise from nonlinearities introduced by the phase contrast transfer function of the electron microscope. Additional uncertainties in the volume measurements arise from errors in the magnification and from the oversimplification inherent in the use of spherically symmetric envelopes. Although the reconstruction presented here was computed with Fourier data truncated at 3.2-nm resolution, the effects of Fourier termination ripples on the density distribution were judged to be minimal, because reconstructions that were computed at higher resolution displayed the same overall radial density distribution despite the presence of higher noise levels.

RESULTS

Electron Microscopy of Frozen-Hydrated and Negatively Stained Virions

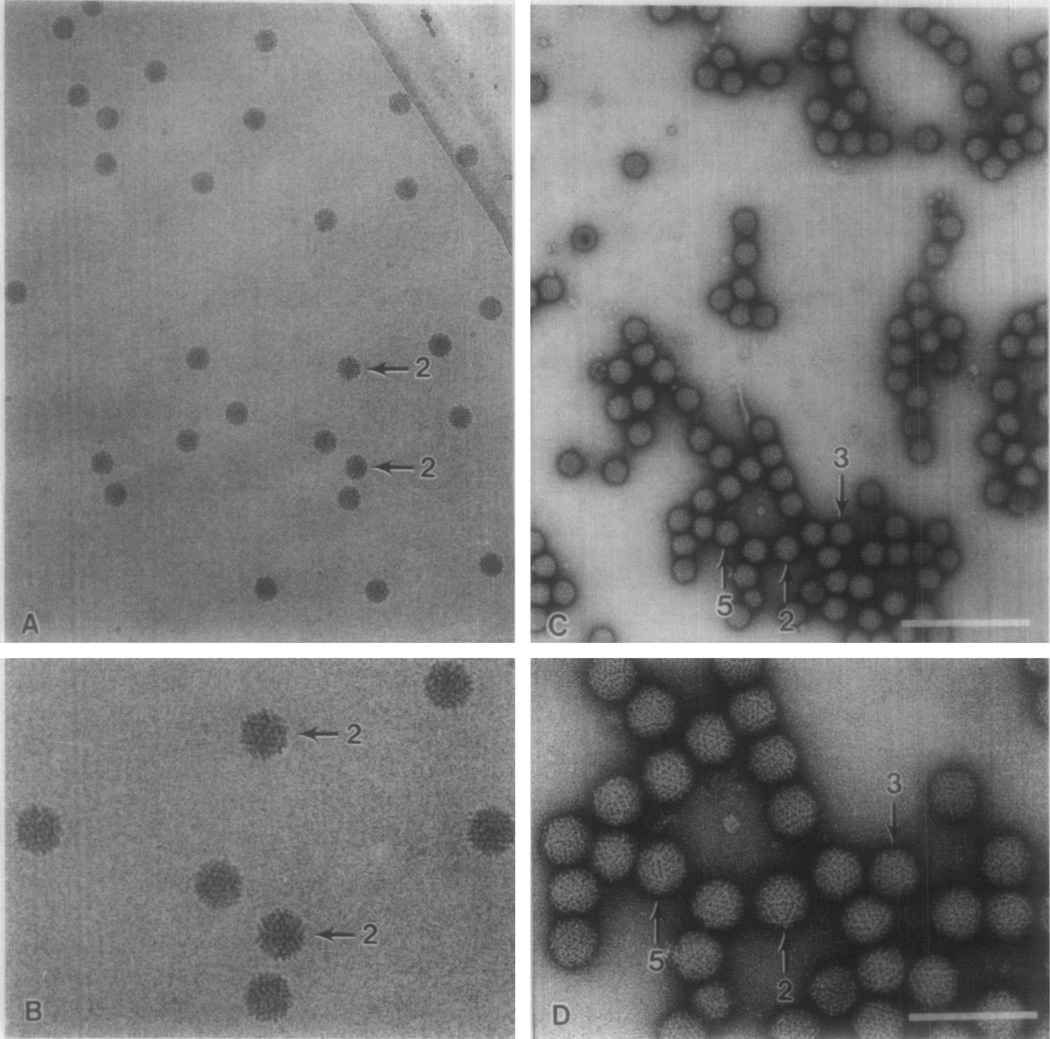

Electron micrographs of frozen-hydrated NβV reveal particles with nearly circular profiles, indicating that the overall shape of the virion is approximately spherical (Fig. 1A). Except for those particles oriented with a twofold axis of symmetry close to the viewing direction, it was difficult to distinguish different particle orientations by eye. Presumably, fine details of the NβV capsid structure were masked as a result of the superposition effects that occur for particles viewed in projection. In the twofold view, however, particles exhibit a distinct, hexagonal profile, and substructure is clearly visible in well-defined, triangular-shaped regions (Fig. 1B, arrows). The average diameter measured for the frozen-hydrated virions was 39.7 ± 1.6 nm. The uniformity in the size and shape of the virions indicates that the native morphology of the virus was well preserved in the vitrified samples examined by electron microscopy.

Fig. 1.

Electron micrographs of frozen-hydrated (A and B) and negatively stained (C and D) NβV samples. Virions viewed close to icosahedral twofold (2) and threefold (3) axes are labeled. The “5” identifies a particle displaying a prominent fivefold vertex in the upper left portion of the particle image. Magnification bars: 200 nm (A, C), 100 nm (B, D).

Negatively stained virions also exhibit circular profiles (Figs. 1C, 1D) although these virions are not as uniform in size and shape as the frozen-hydrated particles. The diameters of stained virions varied between 43.5 nm, for isolated particles that partially flattened in thin layers of stain on the carbon support film, and 36.0 nm, for particles that were densely packed together and embedded in thick layers of stain. The structural features in stained virions were more readily apparent than those in unstained virions because of the high contrast of the stain and because many particles were nonuniformly stained. Such uneven staining often enhances contrast on one side of the particle, thus reducing superposition effects in the projected particle images and producing a much clearer view of the structure (Klug and Finch, 1965). Close inspection of images of stained virions (Figs. 1C, 1D), revealed that the particles did not adsorb to the support film with any preferred orientations. The fivefold vertices and triangular faces of many virions were clearly visible (e.g., the vertex at the top of the particle labeled 5 in Fig. 1D), and characteristic twofold and threefold views were also observed (Fig. 1D).

Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of Frozen-Hydrated Virions

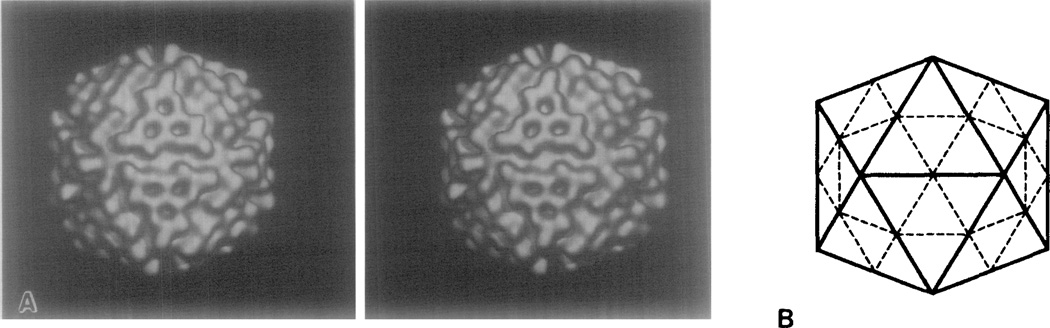

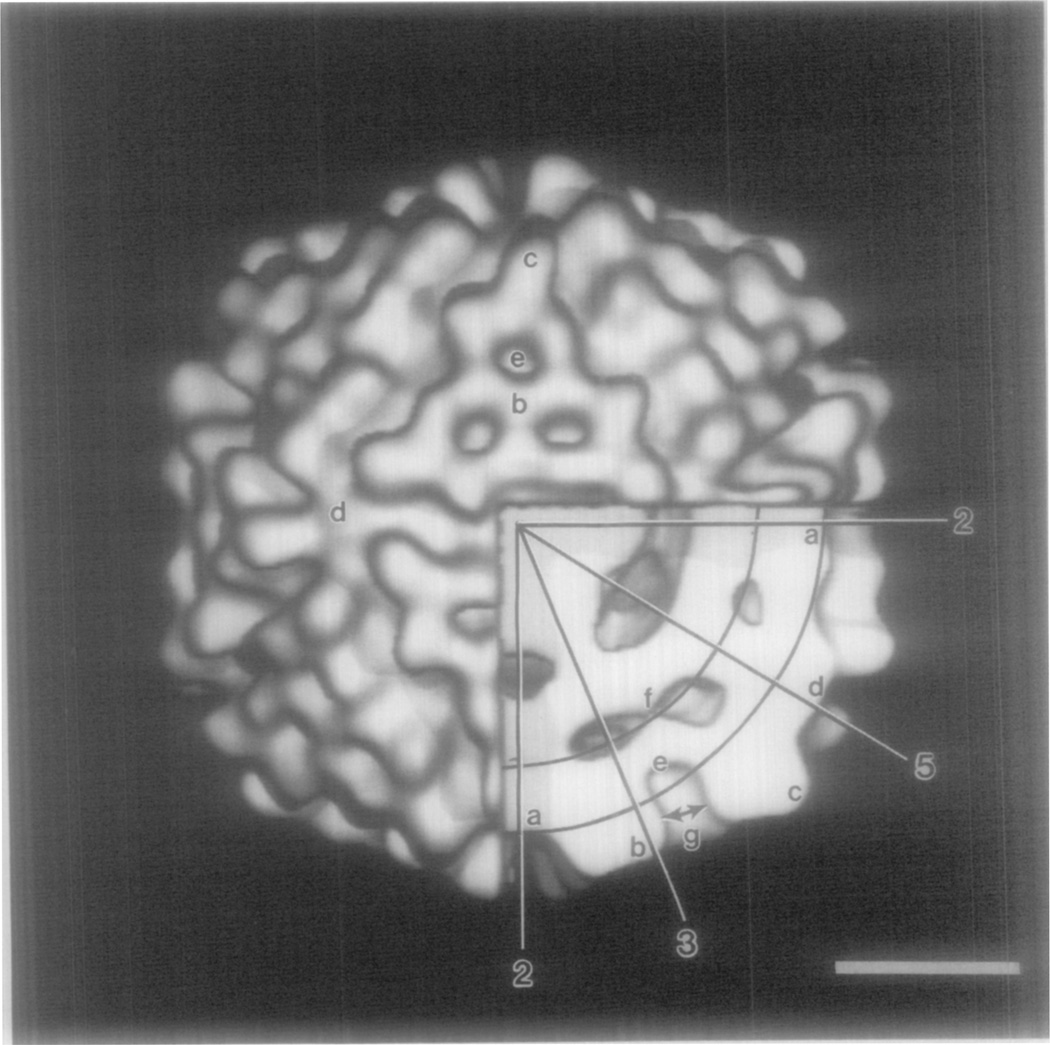

The overall morphology of the outer surface of the NβV capsid is clearly displayed in the stereo, shaded-surface view of the three-dimensional reconstruction (Fig. 2A). Although not enforced by the reconstruction procedure, the T = 4 lattice symmetry of the icosahedral capsid is evident. In a regular icosahedron with T = 4 symmetry, each of the 20 triangular faces is subdivided into four smaller, equilateral triangles (Fig. 2B). In the NβV structure, the region defined by each of these equilateral triangles contains Y-shaped aggregates consisting of three, closely packed, columnar morphological units related by either a quasi or icosahedral threefold axis of symmetry. Each morphological unit is approximately cylindrical, ~4 nm in diameter and ~4 nm high. The axes of the three cylinders of each trimer are approximately parallel with the threefold axis of symmetry that relates the cylinders. The axes of all four trimers of a face are also nearly parallel (i.e., parallel to the icosahedral threefold axis). The distinct icosahedral morphology of the NβV capsid is thus a consequence of the radial positions and orientations of the trimers. The tops of the trimers all lie in nearly the same plane, with the outer trimers projecting slightly further out from the surface compared to the central trimer.

Fig. 2.

Stereo pair of a shaded, surface-representation of the NβV reconstruction (A), and a schematic drawing of a T = 4 icosahedral surface lattice (B) in the same twofold view as (A). Solid lines mark the edge of a parent (T = 1) icosahedron, and broken lines identify the T = 4 triangulated surface lattice.

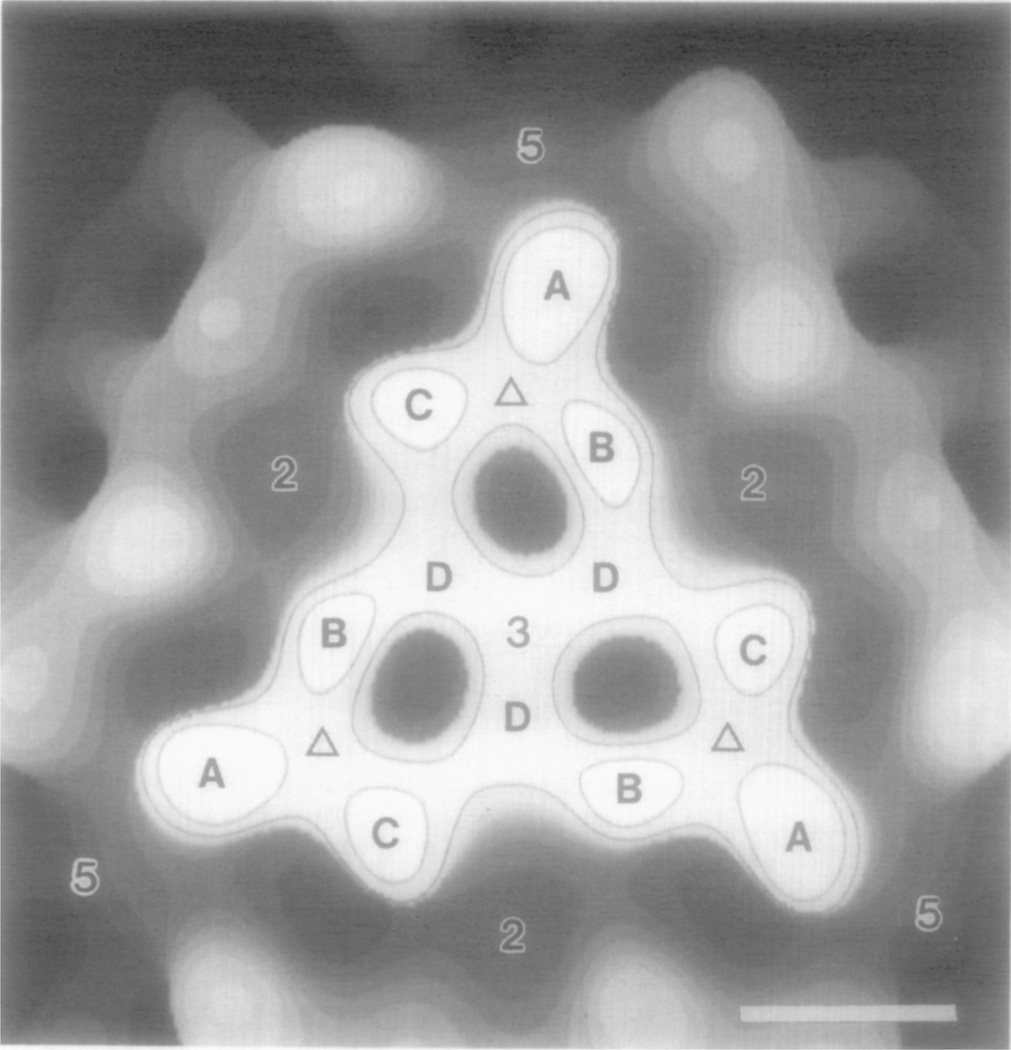

The cylindrical columns of density merge with a smooth, contiguous surface at lower radii. This smooth surface forms the base of the sinuous groove (2.5–4.5 nm wide and ~2.7 nm deep) that separates trimers of adjacent faces and is the base of the “pits” that are between the trimers within a face. The smooth surface also extends over a large area centered at the icosahedral vertex (Fig. 3, “5”; and Fig. 4, position d). The extended, smooth surface and the density directly beneath it forms the contiguous shell that probably contains the intersubunit contacts important for both assembly and stabilization of the capsid structure (see Discussion).

Fig. 3.

Surface representation of the icosahedral face of NβV viewed down the icosahedral threefold axis at the center of the face. A, B, C, and D denote the four morphological units that make up each of the three asymmetric units of an icosahedral face. Density features closest to the viewer are contoured. Locations of the twofold, threefold, and fivefold icosahedral axes are labeled accordingly, and the Δ symbols identify the three quasi threefold axes. Intermorphological unit and intertrimer distances are listed in Table II. Bar = 5 nm.

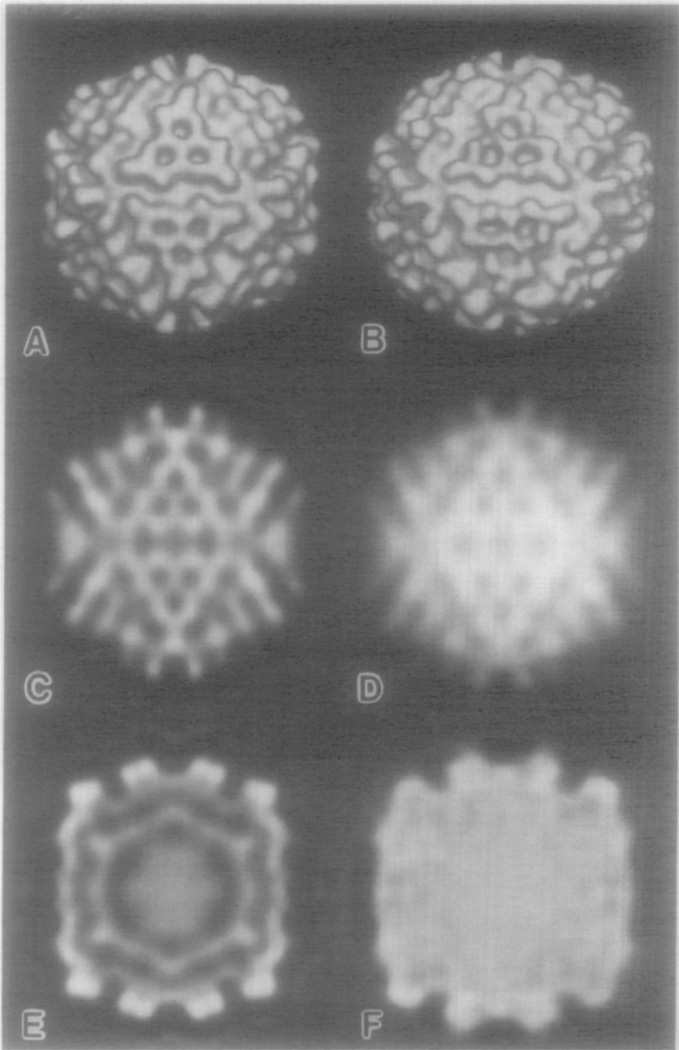

Fig. 5.

Comparisons of NβV reconstructions from images of frozen-hydrated virions (A, C, and E) and negatively stained virions (B, D, and F; Finch et al., 1974) viewed in the same twofold orientation. (A, B) Shaded, surface representations. (C, D) Projected density maps. (E, F) Equatorial slices. The reconstructions were radially scaled to be the same size. Contrast in the frozen-hydrated virion was reversed so protein and RNA density appear bright, and vitreous ice and negative stain appear dark (C, D, E, F). The density at radii <2.5 nm in (F) was attenuated in the same manner as described for the reconstruction from frozen-hydrated images (E; see Materials and Methods).

Fig. 4.

Shaded, surface representation of NβV reconstruction viewed along a twofold axis with a lower right octant removed to show internal features. Approximate boundaries of the contiguous shell of protein are defined by circular arcs. Icosahedral twofold, threefold, and fivefold axes in the equatorial plane are identified and several characteristic features are labeled (a–g), with relevant dimensions listed in Table III. Bar = 10 nm.

The four trimers in the protruding portion of each face of the icosahedron, appear to form a distinct structural unit with six distinct types of intersubunit contacts. Each of the outer trimers only makes contact with the central trimer, and none of the trimers contacts the trimers in adjacent faces. The asymmetric unit of the icosahedral NβV capsid consists of four chemically-identical 61-kDa subunits in four quasi-equivalent environments, three located in an outer trimer (Fig. 3, labeled A, B, C) and one in the central trimer (Fig. 3, labeled D). The A subunit, lies closest to the icosahedral fivefold axis and only contacts B and C subunits within the same trimer. B and C each make three contacts, two with the other two subunits of the same trimer (B–A, B–C and C–A, C–B) and one with a D subunit of the central trimer (B–D and C–D). Each D subunit makes four contacts, two with the other equivalent D subunits of the central trimer (D–D) and one each with a B and C subunit of different outer trimers (D–B in one and D–C in another). Thus, the six distinct types of intersubunit contacts in each protruding face are A–B, A–C, B–C, B–D, C–D, and D–D. The B–D contact appears to be slightly more extensive than the C–D contact as a result of a clockwise rotation3 (~15°) of the outer trimers about the quasi threefold axes (Fig, 3, labeled Δ). The skew orientation results because the A subunit (Fig. 3) lies in a position rotated slightly away from the adjacent fivefold axis (i.e., off the equatorial line between adjacent icosahedral threefold and fivefold axes). Likewise, the B subunit (Fig. 3) is rotated closer to the icosahedral threefold axis and the central trimer, and the C subunit (Fig. 3) is rotated closer to the icosahedral twofold axis. The central trimer is not in a skew orientation (D subunits lie on the equatorial lines between adjacent icosahedral threefold and twofold axes). Thus, the skewed orientations of the outer trimers reduces the distance between the centers of the B and D subunits to 3.0 nm (Table II) and increases the separation between the C and D subunits to 3.8 nm (Table II). Other intersubunit separations are listed in Table II. The centers of the inner and outer trimers are ~6.3 nm apart (Fig. 3 and Table II).

TABLE II.

Interdomain and Intertrimer Separations within the Icosahedral Pacea

| Domain pair | Separation (nm)b |

|---|---|

| A–A | 14.1 |

| A–B | 4.3 |

| A–C | 4.4 |

| B–C | 4.6 |

| B–D | 3.0 |

| C–D | 3.8 |

| D–D | 4.1 |

| Central trimer (3)–outer trimer (Δ) | 6.3 |

Labeling corresponds to that of Fig. 3.

Distance measured between the centers of the domains.

The size, shape, and arrangement of the subunits in the protruding capsid face generate three pits, ~2.4 nm in diameter and ~4.2 nm deep (Fig. 3). These and other features of the external surface, as well as the density distribution beneath the surface, are depicted in a cut-away view of the reconstruction (Fig. 4). The radial positions and dimensions of characteristic features of the NβV structure (labeled in Fig. 4) are listed in Table III. Density in the A sub-unit (Fig. 4, c) extends to the largest radius (21.3 nm) of any feature in the capsid. The B, C, and D subunits extend to maximum radii of 21.0, 21.0, and 20.7 nm, respectively. The base of the pit (Fig. 4, e) is the feature at lowest radius (15.2 nm) in the outer surface. The groove that separates adjacent icosahedral faces slopes upward from a radius of 16.6 nm at the twofold axis to 18.8 nm at the fivefold axis.

TABLE III.

Radial Dimensions in the Reconstructiona

| Surface location | Distance (nm) |

|---|---|

| (a) Twofold axis | 16.6 |

| (b) Threefold axis | 19.4 |

| (c) Highest radius feature | 21.3 |

| (d) Fivefold axis | 18.8 |

| (e) Base of pit | 15.2 |

| (f to d) Maximum contiguous shell thickness | 6.1 |

| (f to e) Minimum contiguous shell thickness | 2.5 |

| (g) Diameter of pit | 2.4 |

The letters in parentheses correspond to the labels in Fig. 4.

Density in the trimeric aggregates appears to merge at lower radii in a contiguous, nonspherical shell whose thickness varies from a minimum of ~2.5 nm beneath the pit (Fig. 4, e to f; Table III) to a maximum of ~6.1 nm at the fivefold axis (Fig. 4, f to d; Table III).

DISCUSSION

Comparison of Reconstructions of Frozen-Hydrated and Negatively Stained Virions

The overall features in the external surface of NβV observed in our reconstruction, computed from images of 25 frozen-hydrated virions (Fig. 5A), are remarkably similar to the surface features revealed in a reconstruction that was computed from images of four negatively stained virions (Fig. 5B; Finch et al., 1974). Both structures exhibit T = 4 capsid symmetry with four Y-shaped, trimeric aggregates in each of the 20 icosahedral faces. The trimers in both reconstructions appear to have similar, columnar-shaped morphological units. The three outer trimers at the corners of each face occupy quasi threefold positions in the icosahedral lattice, and in both reconstructions, lie in similar skewed orientations.

Differences in the surface features of the two reconstructions (cf. Figs. 5A, 5B) indicate that, in comparison to the frozen-hydrated particle, the stained particle has a somewhat rounder profile, and has trimers with slightly smaller volumes thereby forming wider grooves between the faces. These differences could arise from (i) masking of surface features by the negative stain, (ii) rearrangement of the stain induced by the electron beam (e.g., Unwin, 1974; Baker et al., 1983), (iii) distortions caused by surface tension forces imposed on particles suspended in stain over holes in the carbon substrate (Finch et al., 1974; Josephs and Borisy, 1972), or (iv) a higher noise level due to the relatively small number of particles used to compute the reconstruction. Despite these differences, the two reconstructions of NβV are gratifyingly similar.

Projections of the two reconstructions along the twofold direction also show a similar distribution of density features (Figs. 5C, 5D). However, the stained virion appears much brighter overall because stain is essentially excluded from the virion interior (Fig. 5F). Despite this difference, the icosahedral faces are distinct in both projections as are the trimers that are located above and below the twofold axis parallel to the view direction. The twofold view is the only particle orientation that can be directly identified in images of frozen-hydrated specimens (Fig. 1). The skewed orientation of the trimers is not apparent because, in the two-fold view, faces on opposite sides of the virion appear as mirror images of each other and, when they superimpose in projection, chiral information is lost.

Large differences in the distribution of density inside the unstained and stained NβV structures are revealed in equatorial slices through the three-dimensional density maps (cf. Figs. 5E, 5F). These differences mainly reflect the inability of stain to penetrate the outer capsid surface and enhance the contrast of internal features (Moore et al., 1981). The reliability of density features near the center of both maps is poor because the noise level remains highest at this part of the reconstruction (Crowther, 1971). In the frozen-hydrated virion a diffuse region of density below a radius of 8.0 nm, presumably corresponding to the RNA, lies inside a nonspherical region of higher density, separate from the contiguous outer shell. The outer surfaces of the unstained and stained NβV structure, as seen in the thin slice view (Figs. 5E, 5F), appear quite similar, although the cross-sections of the pits are slightly different. In the frozen-hydrated structure, the pit is wider at the base than it is at the outer surface. The stained pit has the opposite profile.

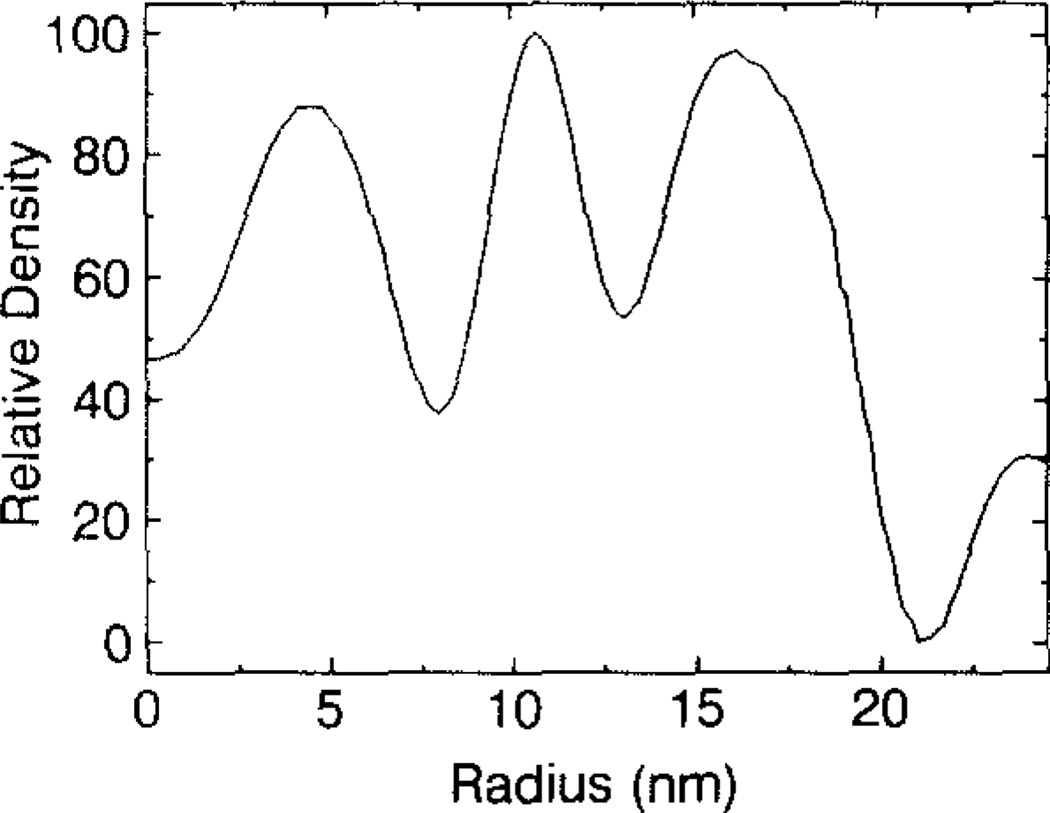

Distribution of Protein and RNA in the NβV Structure

Although it is not possible to directly discriminate between protein and RNA in the three-dimensional reconstruction, in part because the structure has been averaged with a symmetry (icosahedral) that the majority of the RNA is not expected to possess, plausible assignments of relative distributions of these components can be made on the basis of volume estimates from a spherical average. The spherically averaged density plot (Fig. 6) indicates that the NβV structure may be described in simple terms as being subdivided into three spherical annuli (“shells”) with similar average peak densities at radii of~4.5, ~10.6, and ~16.1 nm. The total solvent-excluded volume of the virion out to a radius of 21.3 nm is ~28.5 × 103 nm3. Two hundred forty copies of the 61-kDa major capsid protein, with an estimated partial specific volume of 0.74 cm3/g, would occupy ~18.0 × 103 nm3. The solvent excluded volumes, measured in spherical shells between radii of 0.0~ 8.0, 8.0–13.0, and 13.0–21.3 nm are ~1.78 × 103 nm3, −6.45 × 103 nm3, and −20.28 × 103 nm3, respectively. Thus, the volume in the outer shell (13.0-to 21.3-nm radius) is sufficiently large to completely accommodate all 240 protein subunits. The central region, below 8.0-nm radius, is too small to contain the entire 1800-kDa RNA genome even if it were packed at ~1.65 g/cm3, a typical density for condensed RNA. As Fig. 6 shows, the highest mean density in this region (at ~4.5-nm radius), is about 4.3% lower than the highest mean density in the outer contiguous (protein) shell (at ~ 16.1-nm radius). These calculations assume a density of 1.35 g/cm3 for protein at a radius of 16.1 nm and a density of 0.93 g/cm3 (Dubochet et al., 1988) for vitreous ice at radii larger than 24 nm. Thus, the RNA appears to be packed rather loosely within the central portion of this virion and it is likely that some of the density in the region between 8.0- and 13.1-nm radii represents RNA. Our calculations, which indicate low average packing density for the RNA inside the NβV capsid, are consistent with the unusually low buoyant densities that have been reported for several viruses of the Tetraviridae (Hendry et al., 1985; Moore et al., 1985). The observation that these viruses are fairly impenetrable to small ions has been used to explain the unusually low buoyant densities measured in cesium chloride (Hendry et al., 1985). A similar effect was observed for polio virus (Mapoles et al., 1978).

Fig. 6.

Spherically-averaged, density distribution computed from the NβV reconstruction. Peaks at ~4.5, ~10.6, and ~16.1 nm identify regions of high average density within the virion. The solvent-excluded volumes between radii of 0–8.0, 8.0–13.0, and 13.0–21.3 nm are 1.78 × 103 nm3, 6.45 × 103 nm3, and 20.28 × 103 nm3, respectively. The outermost spherical envelope has sufficient solvent-excluded volume to fully accommodate 240 copies of the 61-kDa capsid protein.

The high density along the fivefold icosahedral axes, at a radius of ~11.9 nm (Fig. 5E), may represent partially or highly ordered RNA as recently observed in bean pod mottle virus, a pseudo T = 3 (strictly T = 1) RNA-containing virus (Chen et al., 1989). The existence of large cavities at radii of~8.0 and 13.0 nm (Figs. 4,5E) also suggests that the RNA is nonuniformly distributed inside the virion.

Similarities in the Subunit Packing in the Contiguous Shells of T = 3 and T = 4 Capsids

The NβV reconstruction at 3.2-nm resolution suggests that the capsid protein is a multidomain sub-unit. The outer region of the particle is dominated by trimeric interactions of cylindrical domains that have a height and diameter of ~4.0 nm (Figs. 3, 4). These outer cylinders would accommodate approximately 40 kDa of protein for each of the 240 sub-units (assuming a partial specific volume for protein of 0.74 cm3/g). The contiguous shell (e.g., between radii 12.7 nm (f) and 15.2 nm (e) in Fig. 4) is ~2.5 nm thick and this would accommodate roughly 21-kDa of protein per subunit. Previous crystallo-graphic studies of RNA viruses that infect eukaryotic cells have shown that all capsid proteins contain an eight-stranded antiparallel β-barrel motif that forms the contiguous shell of the particle (Rossmann and Johnson, 1989). The molecular weight of this portion of the capsid protein is approximately 20-kDa. Based on this precedent and the calculations described, we suggest that the subunits of NβV are composed of a shell-forming domain of ~21-kDa and a protruding domain of ~40 kDa. Although the image reconstruction gives no detail of the subunit organization in the contiguous shell portion of the NβV capsid, we propose that it may be formed by β-barrels arranged according to architectural principles similar to those found in the shells of T = 3 viruses.

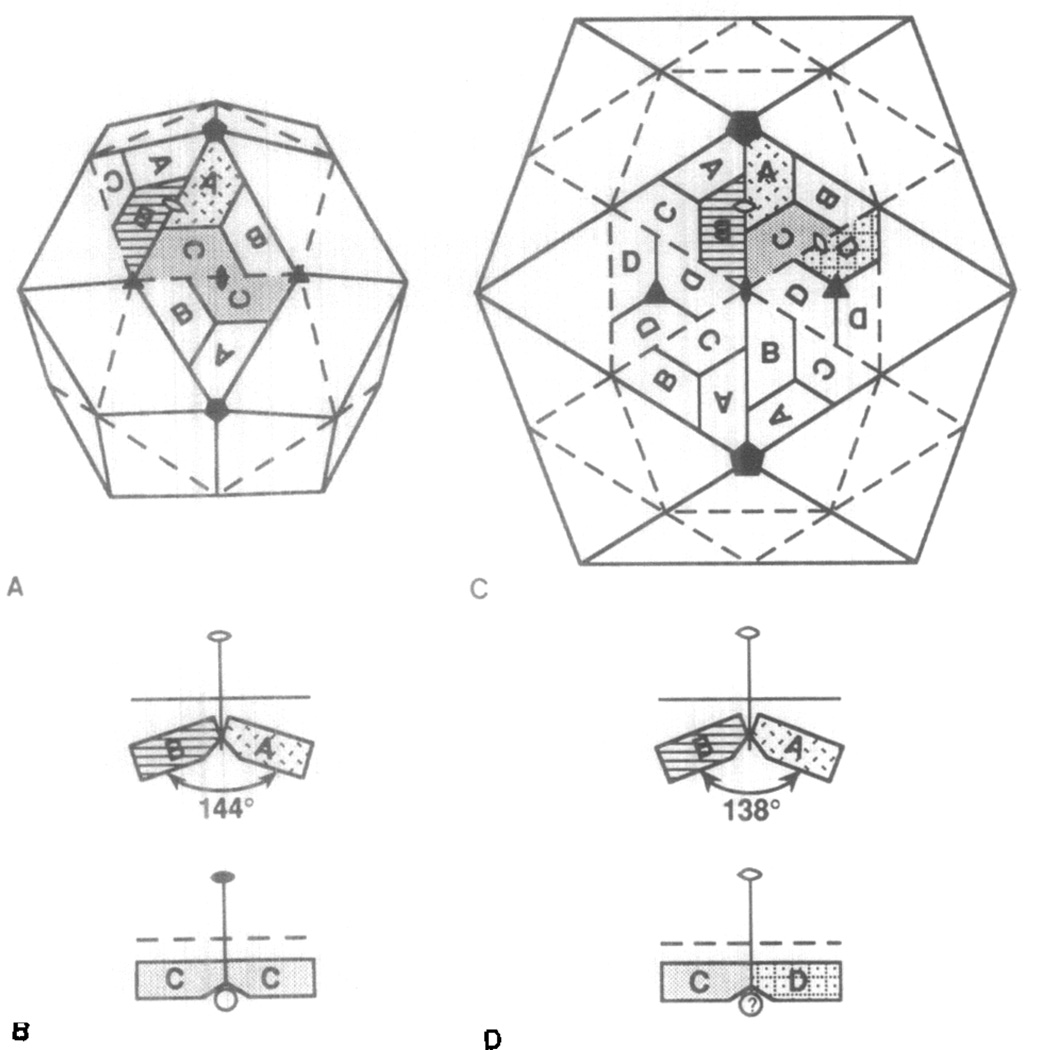

T = 4 and T = 3 structures both contain quasi twofold, quasi threefold, and quasi sixfold symmetry axes in addition to the strict icosahedral symmetry elements. A T = 3 structure based on a rhombic triicontahedron model (Figs. 7A and 7B) depicts the relationship between subunits (trapezoids) seen in the contiguous shells of T - 3 plant and insect viruses. A T = 4 structure, based on a triangulated icosahedron model (Figs. 7C and 7D), illustrates the proposed location of subunits (trapezoids) in the contiguous shell of NβV.

Fig. 7.

Diagrammatic representations of the subunit associations accounting for contiguous shells in T = 3 (A, B) and T = 4 icosahedrons (C, D). Views A (close to an icosahedral twofold axis) and C (along the twofold axis) are presented in the standard crystallographic orientation, which is rotated by 90° with respect to Figs. 2–5 Labeled trapezoids represent the individual capsid subunits. The packing relations, as viewed along an equatorial line within the structure, between C subunits related by the icosahedral twofold (solid ellipse) and between A and B subunits related by the quasi twofold (open ellipse) are shown for the T = 3 structure in panel (B). Likewise, the C and D, and the A and B subunits of the T = 4 structure, related by different quasi twofold axes, are shown in panel (D). A peptide (open circle, panel B) maintains the planar C–C contact as observed in the BBV structure (Hosur et al., 1987). A similar peptide (panel D) may keep the C-D contact in the T = 4 structure planar. Open and closed ellipses, closed triangles, and closed pentagons represent quasi and icosahedral twofold, and icosahedral threefold and fivefold axes, respectively.

The geometry of the T = 3 quasi-equivalent structure is explained by examining the difference between an icosahedral twofold axis (solid ellipse), which relates two C subunits, and a quasi twofold axis (open ellipse), which relates A and B subunits (Fig. 7A). The C subunits lie in the same plane, but the A and B subunits are in planes with a dihedral angle of 144° (Fig. 7B). The T = 4 structure contains two types of quasi twofold axes (Fig. 7C). Like the T = 3 structure, one type relates subunits (C and D) in the same plane, but the other relates subunits (A and B) in different planes with a dihedral angle of 138° (Fig. 7D). The contiguous shell of a hypothetical T = 4 structure may be constructed with the A, B, and C subunits from the quasi-equivalent trimer of the T = 3 asymmetric unit and with the D sub-unit that is related to the C subunit by quasi twofold symmetry. Thus, the model asymmetric unit consists of subunits A, B, C, and D, the four required by the T = 4 lattice symmetry.

A schematic representation of how chemically equivalent subunits form distinct contacts in the T = 3 icosahedron is shown in Fig. 7B. The presence of a 10-residue polypeptide in the groove between the twofold related C subunits in the T = 3 lattice prevents bending that occurs between the A and B sub-units where the peptide is absent (Hosur et al., 1987). A similar mechanism may generate the observed surface lattice for the T = 4 structure in which an inserted peptide could produce a flat C/D contact, and in the absence of the peptide, the angled A/B contact could form (Fig. 7D).

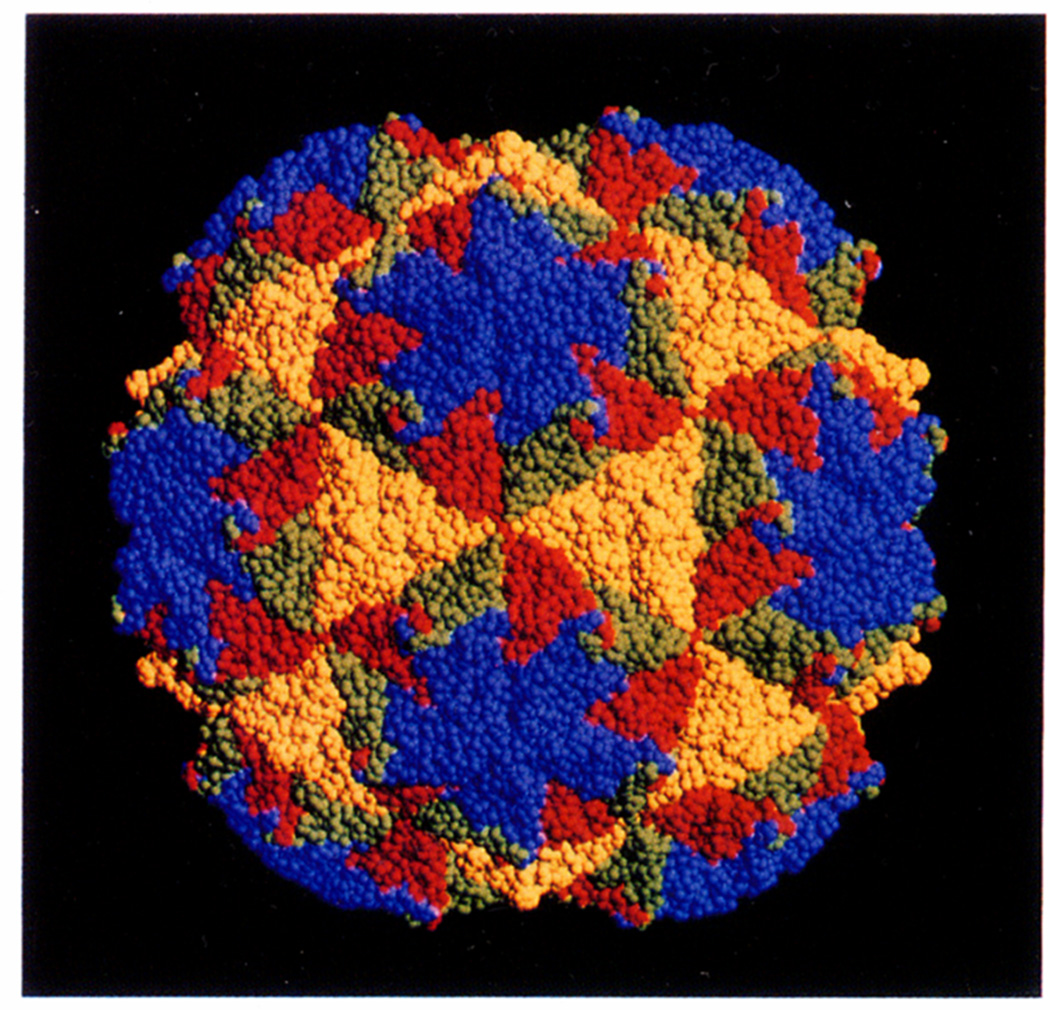

The proposed packing of NβV subunits was modeled by generating a T = 4 structure from the sub-units of the T = 3 black beetle virus (BBV) whose structure has been refined to 0.28-nm resolution (Wery and Johnson, 1989). The capsid subunit of BBV has an eight-stranded, antiparallel, β-barrel core, like most other RNA viruses determined to date, extensions of 80 and 85 amino acids at the N-and C-termini, and a total of 92 residues present as inserts between the strands of the β-barrel. The A, B, and C subunits of the T = 3 asymmetric unit along with the twofold related C subunit of the adjacent asymmetric unit (Fig. 7A) were treated as a single, rigid unit and positioned translationally and radially to form a close-packed, T = 4 icosahedral face after imposing threefold symmetry. The difference in subunit positions related by a quasi threefold axis and a true threefold axis in this model averages only a fraction of an angstrom. Icosahedral symmetry operations were applied to form a complete model (Fig. 8). This model predicts that the inner and outer radii of the β-barrels lie between 13.9 and 16.5 nm. These dimensions reasonably agree with the region of contiguous protein (12.7– 16.6 nm) in the reconstruction from vitrified virions (Fig. 4, arcs). The regions of protein that form the protruding domain of the quasi and icosahedral trimers could be elaborate insertions between the strands of the β-barrel (Hosur et al., 1987) or could be a separate domain at the carboxy terminus similar to the subunits of tomato bushy stunt virus (Harrison et al., 1978).

Fig. 8.

T = 4, space-filling model constructed with the sub-unit coordinates derived from the 0.28-nm refined structure of the T = 3 black beetle virus (BBV) (Hosur et al., 1987). The view orientation is the same as that of Fig. 7 The T = 4 icosahedral asymmetric unit was constructed with the A, B, and two C sub-units (related by an icosahedral twofold axis) of BBV (Fig. 7A). This rigid unit was radially adjusted to form a shell of contiguous, nonoverlapping protein after applying the icosahedral symmetry operations. The A, B, C, and D subunits (Figs. 3, 7C, and 7D) are respectively represented with the colors blue, orange, green, and yellow. Surface protrusions at the quasi and icosahedral threefold axes arise from extended loops in the BBV polypeptide.

Finch et al. (1974) recognized that the icosahedral asymmetric unit of NβV (containing four subunits) does not form a logical assembly unit, and they suggested that the particle may form from preassembled trimers. This assembly hypothesis is consistent with the T = 4 capsid organization described. The detailed model predicts that, prior to assembly, there is probably no difference between the trimers related by icosahedral threefold symmetry (DDD) and trimers related by quasi threefold symmetry (ABC) (Fig. 7C), and it is only after the shell starts to assemble that the two classes of trimers begin to differ slightly. High-resolution crystallographic studies of NβV (Sehnke et al., 1988), and the presumably similar, N. capensis ω virus (NωV) (Cavarelli et al., 1990) are currently underway and will provide definitive answers to these questions.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge M. Pogrund and W. Bomu for technical help, H. Hinkel for photographic assistance, A. Fisher for help in preparing Figs. 2 and 7, J Finch and R. Crowther for providing the three-dimensional density map of the stained NβV virion for comparisons with our reconstruction, and J.-P. Wery for computing the space-filling model shown in Fig. 8 DAH thanks the Director-General of the Department of Environmental Affairs for permission to collect insects in state forests. This research was supported by grants from the NIH to T.S.B. (GM33050) and J.E.J. (GM34220), the Foundation for Research Development to D.A.H., and The Lucille P. Markey Trust to the Center for Macromolecular Structure Research.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: BBV, black beetle virus; kDa, kilodalton; NβV, Nudaurelia capensis β virus; NωV, Nudaurelia capensis ω virus; ssRNA, single-stranded ribonucleic acid.

The absolute hand of the NβV capsid structure is unknown. Although the reconstruction shown has outer trimers skewed to the right (subunit A lies to the right of the equatorial line), it is equally likely that the actual structure is the enantiomorph of the depicted model. Tilting experiments (e.g., Klug and Finch, 1968) might be used to resolve this ambiguity.

REFERENCES

- Abad-Zapatero C, Abdel-Meguid SS, Johnson JE, Leslie AGW, Rayment I, Rossmann MG, Suck D, Tsukihara T. Nature (London) 1980;286:33–39. doi: 10.1038/286033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian M, Dubochet J, Lepault J, McDowall AW. Nature (London) 1984;308:32–36. doi: 10.1038/308032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TS, Caspar DLD, Hollingshead CJ, Good-enough DA. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:204–216. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.1.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TS, Drak J, Bina M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:422–426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TS, Drak J, Bina M. Biophys J. 1989;55:243–253. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82799-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker Ts, Newcomb WW, Booy Fp, Brown JC, Steven AC. J. Virol. 1990;64:563–573. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.563-573.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blundell L, Johnson LN. Protein Crystallography. New York: Academic Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cavarelli J, bomu W, Liljas L, Kim S, Minor W, Much-more S, Schmidt T, Johnson JE, Hendry DA. Acta Cryst. A. 1990 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Chao YC, Scott HA, Young SY., III J. Gen. Virol. 1983;64:1835–1838. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Stauffacher C, Li Y, Schmidt T, Bomu W, Ka-mer G, Shanks M, Lomonossoff G, Johnson JE. Science. 1989;245:154–159. doi: 10.1126/science.2749253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu W. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Chem. 1986;15:237–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.15.060186.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther RA. Phil. Trans. R Soc. London Ser. B. 1971;261:221–230. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1971.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther RA, DeRosier Dj, Klug a. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. A. 1970;317:319–340. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta R, Ghosh A, Dasmahaptera B, Guarino L, Kaesberg P. Nucleic Acid Res. 1984;12:7215–7223. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.18.7215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubochet j, Adrian M, Chang J-J, Homo J-C, Lepault J, McDowall AW, AND SHULTZ P. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1988;21:129–228. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500004297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch JT, Crowther RA, Hendry DA, Struthers JK. J. Gen. Virol. 1974;24:191–200. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-24-1-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen P, Scotti P, Longworth J, Rueckert RR. J. Virol. 1980;35:741–747. doi: 10.1128/jvi.35.3.741-747.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller S. Cell. 1987;48:923–934. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90701-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher TM, Rueckert RR. J. Virol. 1988;62:3399–3406. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.9.3399-3406.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood LK, Moore NF. Microbiologwa. 1981a;4:271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood LK, Moore NF. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1981b;38:305–306. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SC, Olson AJ, Schutt CE, Winkler FK, Bricogne G. Nature London. 1978;276:368–373. doi: 10.1038/276368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayat MA. Principles and Techniques of Electron Microscopy. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry D, Hodgson V, Clark R, Newman J. J. Gen. Virol. 1985;66:627–632. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry DA, Watson G, Reynolds G. Abstr. Fifth Int. Congr. Virol. Strasbourg: France; 1981. p. 284. [Google Scholar]

- Hogle JM, Maeda A, Harrison SC. J. Mol. Biol. 1986;191:625–638. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosur MV, Schmidt T, Tucker RC, Johnson JE, Gallagher TM, Selling BH, Rueckert RR. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 1987;2:167–176. doi: 10.1002/prot.340020302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs R, Borisy G. J. Mol. Biol. 1972;65:127–155. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juckes IRM. Bull. South Afr. Soc. Plant Pathol. Microbiol. 1970;4:18. [Google Scholar]

- Juckes IRM. J. Gen. Virol. 1979;42:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- King LA, Merryweather AT, Moore NF. Ann. Virol. (Inst. Pasteur) 1984;135E:335–342. [Google Scholar]

- Klug A, Finch JT. J. Mol. Biol. 1965;11:403–423. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug A, Finch JT. J. Mol. Biol. 1968;31:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepault J, Leonard K. J. Mol. Biol. 1985;182:431–441. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepault J, Pitt T. EMBO J. 1984;3:101–105. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapoles JP, Anderegg JW, Rueckert RR. Virology. 1978;90:103–111. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan RA, Brisson A, Unwin PNT. Ultramicroscopy. 1984;13:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(84)90051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore NF, Greenwood LK, Rixon KR. Microbiologica. 1981;4:59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Moore NF, Reavy B, King LA. J. Gen. Virol. 1985;66:647–659. [Google Scholar]

- Morris TJ, Hess RT, Pinnock DE. Intervirology. 1979;11:238–247. doi: 10.1159/000149040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson NH, Baker TS, Bomu W, Johnson JE, Hendry DA. In: Proceedings, 45th Annual EMSA Meeting. Bailey GW, editor. Baltimore, MD: 1987. pp. 650–651. [Google Scholar]

- Olson NH, Baker TS. Ultmmicroscopy. 1989;30:281–298. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(89)90057-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavy B, Moore NF. Virology. 1983;131:551–554. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavy B, Moore NF. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1984;44:244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Reinganum C, Robertson JS, Tinsley TW. J. Gen. Virol. 1978;40:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann MG, Johnson JE. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1989;58:533–573. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrag JD, Prasad BVV, Rixon FJ, Chiu W. Cell. 1989;56:651–660. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90587-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehnke PC, Harrington M, Hosur MV, LI Y, Usha R, Tucker RC, Bomu W, Stauffacher Cv, Johnson JE. J. Cryst. Growth. 1988;90:222–230. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M, Vlgers G. Nature (London) 1986;319:631–636. doi: 10.1038/319631a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struthers JK, Hendry DA. J. Gen. Virol. 1974;22:355–362. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-24-1-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima C. Proc. XIIth Internal Cong. Elect. Microsc. 1990;1:242–243. [Google Scholar]

- Tripconey D. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1970;15:268–275. [Google Scholar]

- Unwin PNT. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;87:657–670. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Regenmortel MHV. Serology and Immunochemistry of Plant Viruses. New York: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel RH, Provencher SW, Von Bonsdorff C-H, Adrian M, Dubochet J. Nature (London) 1986;320:533–535. doi: 10.1038/320533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wery J-P, Johnson JE. Anal. Chem. 1989 [Google Scholar]