Abstract

It is believed that obesity has detrimental effects on the coronary circulation. These include immediate changes in coronary arterial vasomotor responsiveness and the development of occlusive large coronary artery disease. Despite its critical role in regulating myocardial perfusion, the altered behavior of coronary resistance arteries, which gives rise to coronary microvascular disease (CMD) is poorly understood in obesity. A chronic, low-grade vascular inflammation has been long considered as one of the main underlying pathology behind CMD. The expanded adipose tissue and the infiltrating macrophages are the major sources of pro-inflammatory mediators that have been implicated in causing inadequate myocardial perfusion and, in a long term, development of heart failure in obese patients. Much less is known the mechanisms regulating the release of these cytokines into the circulation that enable them to exert their remote effects in the coronary microcirculation. This mini review aims to examine recent studies describing alterations in the vasomotor function of coronary resistance arteries and the role of adipose tissue-derived pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipokines in contributing to CMD in obesity. We provide examples of regulatory mechanisms by which adipokines are released from adipose tissue to exert their remote inflammatory effects on coronary microvessels. We identify some of the important challenges and opportunities going forward.

Keywords: Obesity, coronary artery, adipose tissue, TNF, leptin, resistin, IL-6, adiponectin

INTRODUCTION

Obese patients have a higher prevalence of cardiovascular complications contributing to the morbidity and mortality, which in turn accounts for substantial direct and indirect medical and social costs in the United States. Diagnosis and treatment of obstructive large coronary artery disease are established and, for the most part, effective. However, even in the absence of significant occlusion of large coronary arteries, obese patients frequently exhibit evidence of myocardial ischemia. Recent studies have identified that myocardial ischemia is often due to abnormalities in the coronary microcirculation. Despite its critical role in regulating myocardial perfusion, the altered behavior of resistance arteries, which gives rise to coronary microvascular disease (CMD) is poorly understood. CMD is characterized by small artery vasospasm and microvascular obstruction, and is generally found in patients with type-2 diabetes. Morphological changes in microvessels are quite rare in obesity prior to the development of hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes. It has been the view that blood flow to various organs is rarely impaired in obesity, unless occlusive atherosclerosis of the larger arteries develops. Throughout life organs receive normal or even greater than normal blood flow in uncomplicated obesity [1]. This paradigm has been challenged in recent years. Studies reported reduced myocardial perfusion in obese patients [2–5], while others have found that myocardial perfusion is not compromised in obesity [6]. Reduced myocardial perfusion can be due to the reduced vasodilator capacity of coronary resistance vessels, which in some instances represents important markers of cardiovascular risk or may contribute to the pathogenesis of obesity. The underlying mechanisms responsible for reduced vasodilator function of coronary microvessels in obesity, however, remained elusive.

The pathological role and treatment of atherogenic dyslipidemia in the development of obesity-associated large coronary artery disease are well established [7]. In obesity, the endocrine function of adipocytes is altered, which is manifested as reduced adiponectin [8] and elevated levels of leptin, resistin, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [9]. It has been shown that in obesity, adipocyte-derived factors (pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipokines) [8, 9] impair the vasomotor function of coronary resistance arteries [10–13]. Much less is known the mechanisms regulating the release of these cytokines into the circulation, which enable them to exert their remote effects in the body. Adipose tissue possesses a dense network of microvessels ensuring adequate tissue perfusion [14]. It is known that pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipokines, such as TNF, resistin and IL-6 may cause vascular dysfunction [15], but the nature of their remote effects on coronary microvessels remained poorly described. TNF is released from the cell surface by the action of the disintegrin and metalloproteinase (MMP), TNF converting enzyme (TACE), which is regulated by tissue inhibitor of MMP (TIMP)-3 [16]. Interestingly, recent studies showed that TIMP-3/TACE pathway is involved in the control of glucose homeostasis in adipose tissue, and also induced vascular inflammation in models of obesity in mice [17] as well as in patients with diabetes [18]. Several recent studies set out to elucidate mechanisms that are involved in the release of adipokines into the systemic circulation. This review aims to examine studies that focus on alterations in vasomotor dysfunction of coronary arteries in obesity. A description is also provided about the role of proinflammatory cytokines and adipokines that are actively released from the expanded adipose tissue and that are believed to be responsible for mediating a remote inflammatory response in the heart of obese patients.

CORONARY MICROVASCULAR DISEASE IN OBESITY

Increase in body mass, muscular or adipose type, requires a higher cardiac output and expanded intravascular volume to meet the elevated metabolic requirement [19]. In “uncomplicated” obesity, lack of co-morbid conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, increased left ventricular mass may be appropriate for body size [20]. This is considered to be an early adaptation of cardiac function, which accommodates for the higher hemodynamic and metabolic demand in obesity. Cardiac adaptation also implies changes in the coronary circulation. The question is whether changes in the coronary circulation are able to meet the increased metabolic demand in obesity?

Myocardial blood flow, as measured by positron emission tomography (PET) was significantly reduced in post-menopausal women with obesity [2]. In contrast, pre-menopausal women with similar level of obesity exhibited a higher myocardial blood flow at baseline, when compared to lean subjects, while no difference was detected between lean and obese men [21]. By using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, neither the resting myocardial blood flow, nor the adenosine-induced hyperemic flow were correlated with obesity in asymptomatic patients in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), which involved 222 men and women [6]. An elevated myocardial blood flow has also been described in postmenopausal obese women without coronary artery disease, however the increase in resting blood flow was associated with a significantly reduced coronary flow reserve [22]. A study by Schindler et al. found that while baseline myocardial blood flow did not differ, cold pressor test- or dipyridamole-induced increases in blood flow were significantly reduced in obese patients, when compared to lean individuals [3]. Quercioli et al. also found that cold pressor test-induced increase in myocardial blood flow is progressively declined in overweight and obese patients [4]. In another study, coronary flow reserve measured by PET/CT did not differ between control and overweight, whereas it was significantly reduced in obese individuals [5]. Taken together, these studies indicated that while basal myocardial blood flow is not necessary compromised in obese subjects alterations may manifest when the coronary circulation is challenged to mimic the increased metabolic demand in obesity.

The coronary circulation matches blood flow with metabolic requirements by coordinating the vascular resistance in different-sized coronary vessels, which is governed by distinct regulatory mechanisms, such as the myogenic, flow or metabolic control [23, 24]. The large, conduit coronary arteries exert small resistance; resistance to blood flow rises as the vessel diameter decreases in arterioles with a diameter of less than 300 µm. Thus, it seems, it is the response of coronary resistance arteries to pharmacological or physiological stimuli that may be altered in obesity. At present, the impact of obesity on vasomotor regulation of coronary arterioles and the exact underlying mechanisms are not well understood. Coronary arterioles from the heart of obese patients exhibit a reduced endothelium-dependent, bradykinin-induced dilation, however the response is augmented in the simultaneous presence of obesity and hypertension [25]. Oltman et al. have investigated the progression of coronary arterial dysfunction in obese Zucker rats and found that coronary arteriolar dilation to acetylcholine (ACh) was preserved in 16–24 week old animals, but dilations became reduced in 28–36 week old rats [26]. Katakam et al. reported that in 12-week old obese Zucker rats ACh-induced dilation of small coronary arteries was preserved, although a reduced vasodilation to insulin was also reported in this study [27]. Coronary arterioles from pigs fed a high fat diet to induce obesity exhibited impairment of dilation to bradykinin [28], whereas coronary dilation to ACh was preserved in high fat fed, obese rats [29]. More intriguing, Prakash et al. have reported that ACh-induced dilation of coronary arterioles in obese Zucker rats is markedly enhanced [30]. Thus it is possible that the dilator function of coronary microvessels declines during the progression of obesity and with its associated diseases. The important question however remains whether changes - maintained or even enhanced - vasodilator function of coronary resistance arteries are able to meet the elevated metabolic demand in obesity. In this context, in dogs with experimental obesity and metabolic syndrome, in spite of unaltered basal and stimulated coronary blood flow rate there is an apparent mismatch between myocardial perfusion and metabolism, as estimated by the rate of oxygen consumption [31, 32]. Collectively, these studies suggest that during the progression of obesity, altered behavior of coronary resistance arteries leads to a mismatch between blood supply and augmented metabolic requirement, which gives rise to coronary microvascular disease (CMD).

ROLE OF ADIPOKINES IN CONTRIBUTING TO CMD IN OBESITY

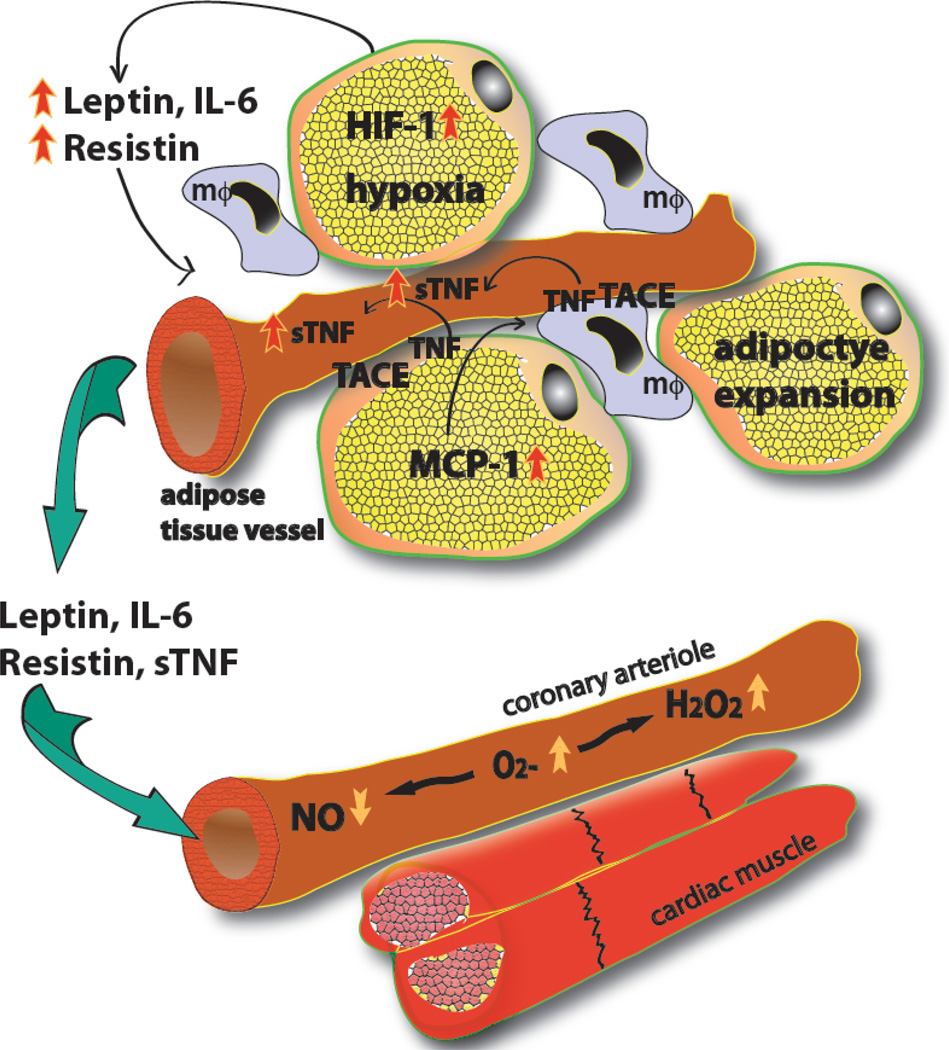

Adipose tissue can represent 18% and 24% of body weight in normal men and women, respectively, or as much as 52% and 74% of body weight in obese man and women, respectively [33]. Adipocytes perform an important endocrine function by secreting numerous cytokines, hormones, and bioactive peptides and also have a key impact on skeletal muscle and liver function to regulate energy homeostasis and metabolism [34]. Adipocyte-derived adipokines include adiponectin [35, 36], leptin [35], resistin [37], vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [38] and also pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF [39], IL-1, IL-6 [40] and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) [41]. It has been found that obesity is associated with decreased circulating level of adiponectin [36] and increased concentrations of leptin [35], TNF, IL-6 [42], MCP-1 [41]. The underlying mechanisms responsible for these alterations remain elusive in obesity, but recent studies propose a key pathological role for hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) in this process. Insufficient adipose tissue perfusion, as the consequence of its rapid expansion has been suggested to cause local hypoxia, which leads to up-regulation of HIF-1α in adipocytes [43, 44]. HIF-1α is a key regulator of the expression of several adipokines, such as leptin, resistin, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), TNF and IL-6 [44] (Fig. 1). In order to provid evidence for its important role a previous study has shown that mice with tissue-specific knockout of adipose HIF-1α were protected against diet-induced obesity and metabolic dysfunction [45]. Whereas in transgenic mice with constitutive activation of HIF-1α selectively in adipose tissue initiated fibrosis and local inflammatory response [44]. Further studies are needed to elucidate whether pharmacological inhibitors of HIF-1α may represent a novel therapeutic modalities to prevent obesity and its associated diseases.

Fig. (1). Adipose tissue-derived cytokines and coronary microvascular vasomotor dysfunction.

In obesity, expansion of adipose tissue leads to tissue hypoxia, which via hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1) results in an increased production of leptin, resistin, TNF, and IL-6. Adipocytes also enhance monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) synthesis, which facilitates macrophage (mΦ) accumulation in adipose tissue. TNF is cleaved by TACE from the cell membrane of adipocytes and macrophages leading to substantial release of soluble form of TNF (sTNF). The secreted adipokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines then reach the coronary microcirculation to exert their remote effects, via inducing production of superoxide anion (O2−·) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in the coronary arteriolar wall, which leads to reduced availability of NO, hence limited vasodilator function.

It is of particular interest in regard to this thematic review article that protein analysis of conditioned medium of primary human adipocytes identified over 300 proteins, most of which are secreted into the systemic circulation [46]. These adipokines may act locally in a paracrine manner, or can be secreted to exert a systemic effect. These systemic effects involve decreased insulin sensitivity in insulin target cells such as adipocytes, hepatocytes and myocytes [47]. Emerging evidence indicates that many of these adipokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines have direct and remote influence on vasomotor function of coronary arterioles in obesity [48]. The impact of various adipokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines on coronary artery disease and vascular function is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies evaluating the vascular impact of various adipokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines in animal models and in human with obesity.

| Level in Obesity | Association with CAD |

In vitro Effect on Coronary Circulation of Animal Models |

In vivo Effect in Humans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| leptin | Increased [94] | Independent risk factor for CAD [95] Predictor of future cardiovascular events in CAD patients [96] Strongly predicts first-ever AMI [97] |

Blunted response to ACh in canine coronary artery [10] Exacerbates coronary endothelial dysfunction in swine [55] |

NO-independent vasodilation in forearm [98] No significant correlation with NO-mediated FBF [99] Positive correlation with MBF [3] |

| adiponectin | Decreased [36] | Lower plasma levels in patients with CAD [100–102] High plasma levels associated with lower risk of AMI [103] |

Restores ACh-induced vasodilation in leptin receptor deficient mice [104] | Decreased FBF in hypoadiponectinemia [105] |

| resistin | Increased [106] | Associated with the severity of CAD [64] | Impairs canine coronary dilation to bradykinin [12] Reduces vasorelaxation in swine coronary arteries [11] |

Negative correlation with FMD [107, 108] |

| TNF | Increased [109–111] | Elevated after AMI [112] G-308A gene polymorphism associated with CAD [113] |

Coronary constriction through endothelin-1 [77, 78] Endothelial dysfunction of coronary arterioles [13–117] |

Increased TNF correlated with FBF [118] Anti-TNF improves FMD [119] Intra-arterial TNF impairs bradykinin- and ACh-induced vasodilatation [120] |

| IL-6 | Increased level [121] Reduced level after weight loss [122] |

Increased risk of CAD [123, 124], Predict vascular events in postmenopausal women [125] |

Overexpression of IL-6 impairs EDHF-mediated dilation in coronary arterioles [126] |

No effect [127], independently related to impaired FMD [128] |

CAD: coronary artery disease, AMI: acute myocardial infarction, FBF: forearm blood flow, MBF: myocardial blood flow, FMD: flow mediated dilation, EDHF: endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizing factor.

Adiponectin

Adiponectin is believed to have positive impact on vascular function [15]. It also acts as an insulin-sensitizing hormone and its down-regulation is considered to be a potential mechanism whereby obesity causes insulin resistance and diabetes [36]. Adiponectin exists in cells and in serum mainly as trimeric, hexameric and high molecular weight forms, and defect in adiponectin multimerization impairs adiponectin stability and secretion, and are correlated with insulin resistance in vivo [49]. The stability and secretion of adiponectin are also regulated at the post-translational modification level via hydroxylation, glycosylation and disulfide bond formation [49]. Impaired multimerization of adiponectin is associated with reduced plasma levels of adiponectin, obesity and insulin resistance [49]. In humans, adiponectin was found to protect the heart from ischemia-reperfusion injury through both AMP kinase- and cyclooxygenase-2-dependent mechanisms [50], however, this capacity is decreased in obesity. Greenstein et al. have found that healthy adipose tissue around human small arteries likely secretes adiponectin that causes vasodilation by increasing NO bioavailability [15]. However, adiponectin from perivascular fat in obese subjects with metabolic syndrome seems to lose its dilator effects [15]. Up to date, there are no studies proving the potential influence vasoactive effects of adiponectin in the human coronary microcirculation.

Leptin

Leptin, a key appetite-regulating hormone primarily acts on hypothalamic neurons to activate catabolic and inhibit anabolic pathway, which can result in weight reduction [51]. Accordingly, lower leptin levels were found to be associated with a higher risk of weight gain in healthy young adults [52]. It is known that β-adrenergic stimulation and also TNF can transiently increase the release of leptin from adipocytes. Higher insulin and cortisol levels can also induce the increase leptin levels, as it has been demonstrated after meals [53]. Hyperinsulinemia and high local cortisol levels up-regulate leptin biosynthesis through post- and pretranscriptional mechanisms [54]. Despite the expected beneficial effects the therapeutic use of leptin has been limited by hypothalamic leptin resistance in obese human [51]. In many obese subjects leptin secretion was found to be significantly higher than in lean subjects, indicating that leptin resistance rather than insufficient leptin production [53]. Thus, pharmacological modulators of leptin receptor sensitivity have been envisioned as promising therapeutic tools.

Interestingly, it has also been posited that in obesity, the altered vasomotor function could arise from the adverse effects of elevated circulating leptin [36]. Knudson et al. have found that pathological concentration of leptin (625 pmol/l) attenuated dilation to ACh in coronary arteries of normal dogs, whereas physiological concentrations (250 pmol/l) were without effect [10]. In the study by Payne et al., leptin, likely to be released from perivascular adipose tissue, elicited reduction of bradykinin-induced coronary relaxation in a swine model of metabolic syndrome; a response, which was mediated by activation of protein kinase C (PKC) [55]. In cultured human umbilical endothelial cells, increased concentration of leptin was associated with increased endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) expression, but also decreased intracellular L-arginine levels, resulting in eNOS uncoupling and consequent eNOS-derived superoxide and peroxynitrite production [56]. Somewhat contradictory, Schindler et al. showed that elevated plasma leptin levels in obese patients exert beneficial effects on the coronary endothelium [57]. Although higher leptin concentrations were associated with impaired arterial distensibility in healthy adolescents [58], acute subcutaneous administration of leptin unexpectedly increased flow-mediated dilation of brachial artery [59]. Furthermore, in obese women, leptin concentration did not predict impaired flow-mediated brachial artery dilation [60]. Thus, the overall impact of adipocyte-derived leptin in contributing to the development of coronary artery dysfunction remains elusive in obesity.

Resistin

Resistin is another adipokine critically involved in metabolic homeostasis. It was found that in adipocytes, leptin and resistin are compartmentalized into different secretory vesicles, whose secretion are oppositely regulated by insulin/glycolytic substrates as well as by the cellular level of cAMP and protein kinase A [61]. The resistin gene is expressed almost exclusively in adipocytes and resistin level has shown to be elevated in obese patients. Insulin and TNF shown to down-regulate resistin expression, whereas glucose and glucocorticoids seem to play important role in its induction [62]. Elevated plasma resistin is correlated with levels of inflammatory markers, including soluble TNF receptor-2, IL-6, and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 along with increased coronary calcium score – a measure of the severity of coronary sclerosis – in 879 asymptomatic subjects [63]. Similar correlation was found in patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease [64]. Furthermore, serum resistin level was found to be independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention [65]. To provide experimental evidence for the direct vascular effect of resistin, porcine coronary arteries were exposed to exogenous resistin in vitro, which resulted in a reduced dilation to bradykinin, via increasing of vascular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [11]. Similarly, Dick et al. have found a reduced bradykinin-induced dilation of canine coronary arteries exposed to resistin; an effect which was, however, independent from increased ROS production and was not affected by endothelial production of NO or proctacyclin [12]. In their study of human saphenous vein endothelial cells, Verma et al. demonstrated that resistin increased expression of endothelin-1 [66]. Endothelin-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor and it is also an important mediator of enhanced ROS production in the vasculature. Over-expression of resistin leads to increased NAD(P)H oxidase activity via increasing the levels of NOX2, NOX4, and p47phox in the rat heart, and results in marked 3-nitrotyrosine formation [67]. Decreased eNOS levels were also observed in human coronary artery endothelial cells incubated with resistin [57]. The authors also demonstrated resistin’s ability to impair mitochondrial respiratory chain function implicating the mitochondria as a key source of ROS production induced by resistin exposure [57].

Taken together, several recent studies indicate that adipokines, such as adiponectin, resistin, and leptin exert direct, detrimental effects on coronary arteriolar dilator function in obesity. These effects, in part, are mediated by loss of NO and enhanced ROS production in coronary arteries of obese subjects. The exact mechanisms by which various adipokines increase vascular ROS production are not entirely understood; it can be mediated either indirectly by agonist such as endothelin-1 [66] and angiotensin II [68] or could be attributed to direct, receptor-mediated activation of various signaling pathways in endothelial and smooth muscle cells, such as JNK, NFκB or PKC [55, 69].

SOURCE(S) AND RELEASE OF TNF FROM ADIPOSE TISSUE

TNF is one of the most important mediators playing a role in the development of endothelial dysfunction in obesity [70–72]. It has been shown that TNF is secreted by adipocytes [73] and its expression in adipose tissue is increased in obesity [72, 74], which correlates with the severity of insulin resistance [75, 76]. It has been found that obese individuals express 2.5-fold higher TNF in adipose tissue relative to lean controls [75]. TNF may elicit a direct vasoconstrictor [77, 78] or vasodilator effects depending on the vascular bed studied [79–81]. While TNF-mediated constriction in coronary or bronchial arteries is mediated by endothelial release of endothelin-1 [77, 78], vasorelaxation in cerebral or brachial arteries involves NO and dilator prostaglandin production [79, 80]. NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent H2O2 production and subsequent activation of calcium-activated potassium channels has also been implicated in TNF-induced vasorelaxation [82]. Recent reports provide evidence that TNF inhibits endothelium-dependent, NO-mediated dilation of coronary arterioles, interferes with ceramide-induced activation of Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK), and leads to subsequent production of superoxide anion [71]. Moreover, TNF via increasing NAD(P)H oxidase-derived ROS production has been implicated in the development of coronary arterial dysfunction in obese Zucker rats [13]. Tesauro et al. have shown that TNF neutralizing antibody, infliximab, ameliorated the blunted vascular reactivity in obese patients, likely via reducing oxidative stress [83]. Thus, evidence indicates that TNF plays a crucial role in the development of coronary microvascular dysfunction in obesity and studies also provided rational for therapeutic intervention, such as the use of TNF neutralizing antibody in cardiovascular prevention.

Emerging evidence indicate a crucial role for mechanisms regulating TNF secretion from adipose tissue contributing to the development of various pathologies associated with obesity. TNF release from human adipose tissue and cultured adipocytes occurs at low levels under control conditions, which is increased substantially in response to LPS stimulation [84]. In obesity, adipose tissue is infiltrated with large number of macrophages [85, 86] that can comprise up to 40% of the cells within adipose tissue [86]. Baker et al. reported increased macrophage infiltration in epicardial adipose tissue when compared to abdominal adipose tissue [87]. Adipose tissue macrophages were shown to contribute to the substantial release of TNF and IL-6 [86]. More recently, Weisberg et al. reported that although differentiated white adipocytes are capable of producing TNF, macrophages from the stromal vascular fraction of adipose tissue are the primary source of adipose tissue-derived TNF. The authors proposed M1 macrophages as the main source of increased TNF production in obesity [86].

How the release of TNF from adipocytes and macrophages is regulated in obesity still remains poorly understood. TNF is synthesized as a 26 kDa transmembrane protein that undergoes cleavage by TNF converting enzyme (TACE, also known as a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-17 (ADAM17)) and is released into the circulation as a soluble, 17 kDa TNF molecule [88, 89]. The cleavage of such membrane bound TNF is a highly regulated process. TACE is naturally inhibited in vivo by tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-3 (TIMP3), which binds to the catalytic domain of the enzyme. The balance between TACE and TIMP3 activities seems to determine serum TNF levels, and a reduction of TIMP3 expression results in an elevation of serum TNF due to unrestricted TACE activity [90]. TACE can undergo several posttranslational modifications (it has several glycosylation and phosphorylation sites), however little is known about its regulation in obesity. At an early stage of the development of obesity, TACE activity seems to be elevated in visceral adipose tissue, but not in liver or skeletal muscle. Interestingly, intraperitoneal injection of exogenous TNF increased TACE activity and protein expression in white adipose tissue of mice [91]. Treatment with the TACE-inhibitor marimastat improved surrogate markers for insulin sensitivity and reversed steatosis in mouse model of diet-induced obesity and leptin deficiency [92]. Adipose tissue from high fat-fed mice exhibited an increase in TACE expression, when compared to control diet fed mice [93]. Whether changes in adipose tissue (adipocyte versus macrophage) TACE activity and consequent release of TNF into the systemic circulation contributes to the development of coronary vasomotor dysfunction in obesity has yet to be elucidated.

SUMMARY

Adipose tissue possesses a dense network of microvessels ensuring sufficient exchange of nutrients and oxygen. The adipose tissue vasculature delivers lipids to their storage depot in the adipocytes and also exports nutrients in response to metabolic need. It is the view that adipokines and other vasoactive mediators are secreted from adipocytes and other cellular elements from the adipose tissue, such as macrophages, and via the adipose tissue microvascular network are delivered into bloodstream to exert their remote effects. In obesity, insufficient adipose tissue perfusion may result in local hypoxia, which increases the levels of hypoxia inducible factor, HIF-1α in adipocytes [43, 44]. HIF-1α may lead to increased synthesis of various inflammatory adipokines, including TNF, IL-6, leptin and resistin [44] (Fig. 1). Emerging evidence indicates that cellular mechanisms regulating the controlled release of various adipokines and proinflammatory cytokines from the adipose tissue are the major determinants of remote coronary microvascular inflammation in obesity and may represent new therapeutic targets for therapeutic intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors works are supported by grant R01 HL104126 (ZB) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall JE, Brands MW, Henegar JR. Mechanisms of hypertension and kidney disease in obesity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;892:91–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin JW, Briesmiester K, Bargardi A, Muzik O, Mosca L, Duvernoy CS. Weight changes and obesity predict impaired resting and endothelium-dependent myocardial blood flow in postmenopausal women. Clin Cardiol. 2005;28(1):13–18. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960280105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schindler TH, Cardenas J, Prior JO, Facta AD, Kreissl MC, Zhang XL, et al. Relationship between increasing body weight, insulin resistance, inflammation, adipocytokine leptin, and coronary circulatory function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(6):1188–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quercioli A, Pataky Z, Montecucco F, Carballo S, Thomas A, Staub C, et al. Coronary Vasomotor Control in Obesity and Morbid Obesity Contrasting Flow Responses With Endocannabinoids, Leptin, and Inflammation. Jacc-Cardiovasc Imag. 2012;5(8):805–815. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vincenti GM, Ambrosio G, Hyacinthe JN, Quercioli A, Seimbille Y, Mach F, et al. Matching between regional coronary vasodilator capacity and corresponding circumferential strain in individuals with normal and increasing body weight. J Nucl Cardiol. 2012;19(4):693–703. doi: 10.1007/s12350-012-9570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Jerosch-Herold M, Jacobs DR, Jr, Shahar E, Folsom AR. Coronary risk factors and myocardial perfusion in asymptomatic adults: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(3):565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bashan N, Kovsan J, Kachko I, Ovadia H, Rudich A. Positive and negative regulation of insulin signaling by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(1):27–71. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(3):439–451. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg AH, Scherer PE. Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2005;96(9):939–949. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knudson JD, Dincer UD, Zhang C, Swafford AN, Jr, Koshida R, Picchi A, et al. Leptin receptors are expressed in coronary arteries, and hyperleptinemia causes significant coronary endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(1):H48–H56. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01159.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kougias P, Chai H, Lin PH, Lumsden AB, Yao Q, Chen C. Adipocyte-derived cytokine resistin causes endothelial dysfunction of porcine coronary arteries. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(4):691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dick GM, Katz PS, Farias M, 3rd, Morris M, James J, Knudson JD, et al. Resistin impairs endothelium-dependent dilation to bradykinin, but not acetylcholine, in the coronary circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291(6):H2997–H3002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01035.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picchi A, Gao X, Belmadani S, Potter BJ, Focardi M, Chilian WM, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces endothelial dysfunction in the prediabetic metabolic syndrome. Circ Res. 2006;99(1):69–77. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000229685.37402.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutkowski JM, Davis KE, Scherer PE. Mechanisms of obesity and related pathologies: the macro- and microcirculation of adipose tissue. FEBS J. 2009;276(20):5738–5746. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07303.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenstein AS, Khavandi K, Withers SB, Sonoyama K, Clancy O, Jeziorska M, et al. Local inflammation and hypoxia abolish the protective anticontractile properties of perivascular fat in obese patients. Circulation. 2009;119(12):1661–1670. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.821181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, et al. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature. 1997;385(6618):729–733. doi: 10.1038/385729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiorentino L, Vivanti A, Cavalera M, Marzano V, Ronci M, Fabrizi M, et al. Increased tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme activity induces insulin resistance and hepatosteatosis in mice. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):103–110. doi: 10.1002/hep.23250. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monroy A, Kamath S, Chavez AO, Centonze VE, Veerasamy M, Barrentine A, et al. Impaired regulation of the TNF-alpha converting enzyme/tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 proteolytic system in skeletal muscle of obese type 2 diabetic patients: a new mechanism of insulin resistance in humans. Diabetologia. 2009;52(10):2169–2181. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1451-3. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavie CJ, Messerli FH. Cardiovascular adaptation to obesity and hypertension. Chest. 1986;90(2):275–279. doi: 10.1378/chest.90.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iacobellis G. True uncomplicated obesity is not related to increased left ventricular mass and systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(11):2257. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.012. author reply 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peterson LR, Soto PF, Herrero P, Mohammed BS, Avidan MS, Schechtman KB, et al. Impact of gender on the myocardial metabolic response to obesity. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1(4):424–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motivala AA, Rose PA, Kim HM, Smith YR, Bartnik C, Brook RD, et al. Cardiovascular risk, obesity, and myocardial blood flow in postmenopausal women. J Nucl Cardiol. 2008;15(4):510–517. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chilian WM. Coronary microcirculation in health and disease. Summary of an NHLBI workshop. Circulation. 1997;95(2):522–528. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones CJ, Kuo L, Davis MJ, Chilian WM. Regulation of coronary blood flow: coordination of heterogeneous control mechanisms in vascular microdomains. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;29(5):585–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fulop T, Jebelovszki E, Erdei N, Szerafin T, Forster T, Edes I, et al. Adaptation of vasomotor function of human coronary arterioles to the simultaneous presence of obesity and hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(11):2348–2354. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.147991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oltman CL, Richou LL, Davidson EP, Coppey LJ, Lund DD, Yorek MA. Progression of coronary and mesenteric vascular dysfunction in Zucker obese and Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291(4):H1780–H1787. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01297.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katakam PV, Tulbert CD, Snipes JA, Erdos B, Miller AW, Busija DW. Impaired insulin-induced vasodilation in small coronary arteries of Zucker obese rats is mediated by reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288(2):H854–H860. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00715.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henderson KK, Turk JR, Rush JW, Laughlin MH. Endothelial function in coronary arterioles from pigs with early-stage coronary disease induced by high-fat, high-cholesterol diet: effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97(3):1159–1168. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00261.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jebelovszki E, Kiraly C, Erdei N, Feher A, Pasztor ET, Rutkai I, et al. High-fat diet-induced obesity leads to increased NO sensitivity of rat coronary arterioles: role of soluble guanylate cyclase activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294(6):H2558–H2564. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01198.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prakash R, Mintz JD, Stepp DW. Impact of obesity on coronary microvascular function in the Zucker rat. Microcirculation. 2006;13(5):389–396. doi: 10.1080/10739680600745919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Setty S, Sun W, Tune JD. Coronary blood flow regulation in the prediabetic metabolic syndrome. Basic Res Cardiol. 2003;98(6):416–423. doi: 10.1007/s00395-003-0418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borbouse L, Dick GM, Payne GA, Payne BD, Svendsen MC, Neeb ZP, et al. Contribution of BK(Ca) channels to local metabolic coronary vasodilation: Effects of metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298(3):H966–H973. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00876.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leibel RL, Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J. Changes in energy expenditure resulting from altered body weight. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(10):621–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503093321001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kadowaki T, Hara K, Yamauchi T, Terauchi Y, Tobe K, Nagai R. Molecular mechanism of insulin resistance and obesity. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228(10):1111–1117. doi: 10.1177/153537020322801003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahima RS, Qi Y, Singhal NS, Jackson MB, Scherer PE. Brain adipocytokine action and metabolic regulation. Diabetes. 2006;55(Suppl 2):S145–S154. doi: 10.2337/db06-s018. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1784–1792. doi: 10.1172/JCI29126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel SD, Rajala MW, Rossetti L, Scherer PE, Shapiro L. Disulfide-dependent multimeric assembly of resistin family hormones. Science. 2004;304(5674):1154–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.1093466. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S. Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyazawa-Hoshimoto S, Takahashi K, Bujo H, Hashimoto N, Yagui K, Saito Y. Roles of degree of fat deposition and its localization on VEGF expression in adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288(6):E1128–E1136. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00003.2004. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maury E, Noel L, Detry R, Brichard SM. In vitro hyperresponsiveness to tumor necrosis factor-alpha contributes to adipokine dysregulation in omental adipocytes of obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(4):1393–1400. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bastard JP, Lagathu C, Caron M, Capeau J. Point-counterpoint: Interleukin-6 does/does not have a beneficial role in insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(2):821–822. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01353.2006. [Comment Letter]. author reply 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa KI, Kitazawa R, et al. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(6):1494–1505. doi: 10.1172/JCI26498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pickup JC, Chusney GD, Thomas SM, Burt D. Plasma interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha and blood cytokine production in type 2 diabetes. Life Sci. 2000;67(3):291–300. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trayhurn P, Wang B, Wood IS. Hypoxia in adipose tissue: a basis for the dysregulation of tissue function in obesity? Br J Nutr. 2008;100(2):227–235. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508971282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halberg N, Khan T, Trujillo ME, Wernstedt-Asterholm I, Attie AD, Sherwani S, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha induces fibrosis and insulin resistance in white adipose tissue. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(16):4467–4483. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00192-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang CT, Qu AJ, Matsubara T, Chanturiya T, Jou W, Gavrilova O, et al. Disruption of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 in Adipocytes Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Decreases Adiposity in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Diabetes. 2011;60(10):2484–2495. doi: 10.2337/db11-0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lehr S, Hartwig S, Lamers D, Famulla S, Muller S, Hanisch FG, et al. Identification and Validation of Novel Adipokines Released from Primary Human Adipocytes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(1) doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osborn O, Olefsky JM. The cellular and signaling networks linking the immune system and metabolism in disease. Nat Med. 2012;18(3):363–374. doi: 10.1038/nm.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ouwens DM, Sell H, Greulich S, Eckel J. The role of epicardial and perivascular adipose tissue in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14(9):2223–2234. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu ML, Liu F. Transcriptional and post-translational regulation of adiponectin. Biochem J. 2010;425:41–52. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shibata R, Sato K, Pimentel DR, Takemura Y, Kihara S, Ohashi K, et al. Adiponectin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through AMPK- and COX-2 dependent mechanisms. Nat Med. 2005;11(10):1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/nm1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jung CH, Kim MS. Molecular mechanisms of central leptin resistance in obesity. Arch Pharm Res. 2013;36(2):201–207. doi: 10.1007/s12272-013-0020-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allard C, Doyon M, Brown C, Carpentier AC, Langlois MF, Hivert MF. Lower leptin levels are associated with higher risk of weight gain over 2 years in healthy young adults. Appl Physiol Nutr Me. 2013;38(3):280–285. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2012-0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fried SK, Ricci MR, Russell CD, Laferrere B. Regulation of leptin production in humans. J Nutr. 2000;130(12):3127S–3131S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.12.3127S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee MJ, Wang YX, Ricci MR, Sullivan S, Russell CD, Fried SK. Acute and chronic regulation of leptin synthesis, storage, and secretion by insulin and dexamethasone in human adipose tissue. Am J Physiol-Endoc M. 2007;292(3):E858–E864. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00439.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Payne GA, Borbouse L, Kumar S, Neeb Z, Alloosh M, Sturek M, et al. Epicardial perivascular adipose-derived leptin exacerbates coronary endothelial dysfunction in metabolic syndrome via a protein kinase C-beta pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(9):1711–1717. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.210070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Korda M, Kubant R, Patton S, Malinski T. Leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol-Heart C. 2008;295(4):H1514–H1521. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00479.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen C, Jiang J, Lu JM, Chai H, Wang X, Lin PH, et al. Resistin decreases expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase through oxidative stress in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299(1):H193–H201. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00431.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singhal A, Farooqi IS, Cole TJ, O'Rahilly S, Fewtrell M, Kattenhorn M, et al. Influence of leptin on arterial distensibility: a novel link between obesity and cardiovascular disease? Circulation. 2002;106(15):1919–1924. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000033219.24717.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brook RD, Bard RL, Bodary PF, Eitzman DT, Rajagopalan S, Sun Y, et al. Blood pressure and vascular effects of leptin in humans. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2007;5(3):270–274. doi: 10.1089/met.2006.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oflaz H, Ozbey N, Mantar F, Genchellac H, Mercanoglu F, Sencer E, et al. Determination of endothelial function and early atherosclerotic changes in healthy obese women. Diabetes Nutr Metab. 2003;16(3):176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ye F, Than A, Zhao YY, Goh KH, Chen P. Vesicular storage, vesicle trafficking, and secretion of leptin and resistin: the similarities, differences, and interplays. J Endocrinol. 2010;206(1):27–36. doi: 10.1677/JOE-10-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Banerjee RR, Lazar MA. Resistin: molecular history and prognosis. J Mol Med-Jmm. 2003;81(4):218–226. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0428-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reilly MP, Lehrke M, Wolfe ML, Rohatgi A, Lazar MA, Rader DJ. Resistin is an inflammatory marker of atherosclerosis in humans. Circulation. 2005;111(7):932–939. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155620.10387.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ohmori R, Momiyama Y, Kato R, Taniguchi H, Ogura M, Ayaori M, et al. Associations between serum resistin levels and insulin resistance, inflammation, and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(2):379–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Momiyama Y, Ohmori R, Uto-Kondo H, Tanaka N, Kato R, Taniguchi H, et al. Serum Resistin Levels and Cardiovascular Events in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2011;18(2):108–114. doi: 10.5551/jat.6023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verma S, Li SH, Wang CH, Fedak PW, Li RK, Weisel RD, et al. Resistin promotes endothelial cell activation: further evidence of adipokine-endothelial interaction. Circulation. 2003;108(6):736–740. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084503.91330.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chemaly ER, Hadri L, Zhang S, Kim M, Kohlbrenner E, Sheng J, et al. Long-term in vivo resistin overexpression induces myocardial dysfunction and remodeling in rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wassmann S, Stumpf M, Strehlow K, Schmid A, Schieffer B, Bohm M, et al. Interleukin-6 induces oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction by overexpression of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Circ Res. 2004;94(4):534–541. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000115557.25127.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kusminski CM, da Silva NF, Creely SJ, Fisher FM, Harte AL, Baker AR, et al. The in vitro effects of resistin on the innate immune signaling pathway in isolated human subcutaneous adipocytes. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2007;92(1):270–276. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang JYO, Park Y, Zhang HR, Xu XB, Laine GA, Dellsperger KC, et al. Feed-forward signaling of TNF-alpha and NF-kappa B via IKK-beta pathway contributes to insulin resistance and coronary arteriolar dysfunction in type 2 diabetic mice. Am J Physiol-Heart C. 2009;296(6):H1850–H1858. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01199.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang CH, Hein TW, Wang W, Ren Y, Shipley RD, Kuo L. Activation of JNK and xanthine oxidase by TNF-alpha impairs nitric oxide-mediated dilation of coronary arterioles. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40(2):247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Virdis A, Santini F, Colucci R, Duranti E, Salvetti G, Rugani I, et al. Vascular Generation of Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Reduces Nitric Oxide Availability in Small Arteries From Visceral Fat of Obese Patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(3):238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose Expression of Tumor-Necrosis-Factor-Alpha - Direct Role in Obesity-Linked Insulin Resistance. Science. 1993;259(5091):87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dandona P, Weinstock R, Thusu K, Abdel-Rahman E, Aljada A, Wadden T. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in sera of obese patients: Fall with weight loss. J Clin Endocr Metab. 1998;83(8):2907–2910. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.8.5026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, Atkinson RL, Spiegelman BM. Increased Adipose-Tissue Expression of Tumor-Necrosis-Factor- Alpha in Human Obesity and Insulin-Resistance. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(5):2409–2415. doi: 10.1172/JCI117936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kern PA, Saghizadeh M, Ong JM, Bosch RJ, Deem R, Simsolo RB. The Expression of Tumor-Necrosis-Factor in Human Adipose-Tissue - Regulation by Obesity, Weight-Loss, and Relationship to Lipoprotein-Lipase. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(5):2111–2119. doi: 10.1172/JCI117899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Klemm P, Warner TD, Hohlfeld T, Corder R, Vane JR. Endothelin-1 Mediates Ex-Vivo Coronary Vasoconstriction Caused by Exogenous and Endogenous Cytokines. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(7):2691–2695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wagner EM. TNF-alpha induced bronchial vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol-Heart C. 2000;279(3):H946–H951. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baudry N, Vicaut E. Role of Nitric-Oxide in Effects of Tumor-Necrosis-Factor-Alpha on Microcirculation in Rat. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75(6):2392–2399. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.6.2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brian JE, Faraci FM. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced dilatation of cerebral arterioles. Stroke. 1998;29(2):509–515. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Patel JN, Jager A, Schalkwijk C, Corder R, Douthwaite JA, Yudkin JS, et al. Effects of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in the human forearm: blood flow and endothelin-I release. Clin Sci. 2002;103(4):409–415. doi: 10.1042/cs1030409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cheranov SY, Jaggar JH. TNF-alpha dilates cerebral arteries via NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent Ca2+ spark activation. Am J Physiol-Cell. Ph. 2006;290(4):C964–C971. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00499.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tesauro M, Schinzari F, Rovella V, Melina D, Mores N, Barini A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonism improves vasodilation during hyperinsulinemia in metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(7):1439–1441. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sewter CP, Digby JE, Blows F, Prins J, O'Rahilly S. Regulation of tumour necrosis factor-alpha release from human adipose tissue in vitro. J Endocrinol. 1999;163(1):33–38. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1630033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu HY, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan Q, Yang DS, Chou CJ, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baker AR, da Silva NF, Quinn DW, Harte AL, Pagano D, Bonser RS, et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue expresses a pathogenic profile of adipocytokines in patients with cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5 doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kriegler M, Perez C, Defay K, Albert I, Lu SD. A Novel Form of Tnf/Cachectin Is a Cell-Surface Cyto-Toxic Transmembrane Protein - Ramifications for the Complex Physiology of Tnf. Cell. 1988;53(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moss ML, Jin SLC, Milla ME, Burkhart W, Carter HL, Chen WJ, et al. Cloning of a disintegrin metalloproteinase that processes precursor tumour-necrosis factor-alpha. Nature. 1997;385(6618):733–736. doi: 10.1038/385733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Federici M, Hribal ML, Menghini R, Kanno H, Marchetti V, Porzio O, et al. Timp3 deficiency in insulin receptor-haploinsufficient mice promotes diabetes and vascular inflammation via increased TNF-alpha. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3494–3505. doi: 10.1172/JCI26052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kawasaki S, Motoshima H, Hanatani S, Takaki Y, Igata M, Tsutsumi A, et al. Regulation of TNF alpha converting enzyme activity in visceral adipose tissue of obese mice. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2013;430(4):1189–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.de Meijer VE, Le HD, Meisel JA, Sharma AK, Popov Y, Puder M. Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha-Converting Enzyme Inhibition Reverses Hepatic Steatosis and Improves Insulin Sensitivity Markers and Surgical Outcome in Mice. Plos One. 2011;6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gupte M, Boustany-Kari CM, Bharadwaj K, Police S, Thatcher S, Gong MC, et al. ACE2 is expressed in mouse adipocytes and regulated by a high-fat diet. Am J Physiol-Reg I. 2008;295(3):R781–R788. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00183.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McConway MG, Johnson D, Kelly A, Griffin D, Smith J, Wallace AM. Differences in circulating concentrations of total, free and bound leptin relate to gender and body composition in adult humans. Ann Clin Biochem. 2000;37(Pt 5):717–723. doi: 10.1258/0004563001899771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wallace AM, McMahon AD, Packard CJ, Kelly A, Shepherd J, Gaw A, et al. Plasma leptin and the risk of cardiovascular disease in the west of Scotland coronary prevention study (WOSCOPS) Circulation. 2001;104(25):3052–3056. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.101061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wolk R, Berger P, Lennon RJ, Brilakis ES, Johnson BD, Somers VK. Plasma leptin and prognosis in patients with established coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(9):1819–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Soderberg S, Ahren B, Jansson JH, Johnson O, Hallmans G, Asplund K, et al. Leptin is associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction. J Intern Med. 1999;246(4):409–418. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nakagawa K, Higashi Y, Sasaki S, Oshima T, Matsuura H, Chayama K. Leptin causes vasodilation in humans. Hypertens Res. 2002;25(2):161–165. doi: 10.1291/hypres.25.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cleland SJ, Sattar N, Petrie JR, Forouhi NG, Elliott HL, Connell JM. Endothelial dysfunction as a possible link between C-reactive protein levels and cardiovascular disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;98(5):531–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Okamoto Y, et al. Novel modulator for endothelial adhesion molecules: adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin. Circulation. 1999;100(25):2473–2476. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.25.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kumada M, Kihara S, Sumitsuji S, Kawamoto T, Matsumoto S, Ouchi N, et al. Association of hypoadiponectinemia with coronary artery disease in men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(1):85–89. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000048856.22331.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rothenbacher D, Brenner H, Marz W, Koenig W. Adiponectin, risk of coronary heart disease and correlations with cardiovascular risk markers. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(16):1640–1646. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pischon T, Girman CJ, Hotamisligil GS, Rifai N, Hu FB, Rimm EB. Plasma adiponectin levels and risk of myocardial infarction in men. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1730–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang H, Park Y, Zhang C. Coronary and aortic endothelial function affected by feedback between adiponectin and tumor necrosis factor alpha in type 2 diabetic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 30(11):2156–2163. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.214700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shimabukuro M, Higa N, Asahi T, Oshiro Y, Takasu N, Tagawa T, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia is closely linked to endothelial dysfunction in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(7):3236–3240. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Azuma K, Katsukawa F, Oguchi S, Murata M, Yamazaki H, Shimada A, et al. Correlation between serum resistin level and adiposity in obese individuals. Obes Res. 2003;11(8):997–1001. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lupattelli G, Marchesi S, Ronti T, Lombardini R, Bruscoli S, Bianchini R, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in vivo is related to monocyte resistin mRNA expression. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2007;32(4):373–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2007.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang B, Li M, Chen B, Li TD. Resistin involved in endothelial dysfunction among preclinical Tibetan male young adults. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 13(4):420–425. doi: 10.1177/1470320312444745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pfeiffer A, Janott J, Mohlig M, Ristow M, Rochlitz H, Busch K, et al. Circulating tumor necrosis factor alpha is elevated in male but not in female patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Horm Metab Res. 1997;29(3):111–114. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Katsuki A, Sumida Y, Murashima S, Murata K, Takarada Y, Ito K, et al. Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha are increased in obese patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(3):859–862. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nilsson J, Jovinge S, Niemann A, Reneland R, Lithell H. Relation between plasma tumor necrosis factor-alpha and insulin sensitivity in elderly men with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18(8):1199–1202. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.8.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Pfeffer M, Sacks F, Lepage S, Braunwald E. Elevation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and increased risk of recurrent coronary events after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;101(18):2149–2153. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.18.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhang HF, Xie SL, Wang JF, Chen YX, Wang Y, Huang TC. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha G-308A gene polymorphism and coronary heart disease susceptibility: an updated meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 127(5):400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhang C, Hein TW, Wang W, Ren Y, Shipley RD, Kuo L. Activation of JNK and xanthine oxidase by TNF-alpha impairs nitric oxide-mediated dilation of coronary arterioles. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40(2):247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gao X, Xu X, Belmadani S, Park Y, Tang Z, Feldman AM, et al. TNF-alpha contributes to endothelial dysfunction by upregulating arginase in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(6):1269–1275. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhang C, Xu X, Potter BJ, Wang W, Kuo L, Michael L, et al. TNF-alpha contributes to endothelial dysfunction in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(3):475–480. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000201932.32678.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gao X, Zhang H, Belmadani S, Wu J, Xu X, Elford H, et al. Role of TNF-alpha-induced reactive oxygen species in endothelial dysfunction during reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(6):H2242–H2249. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00587.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Katz SD, Rao R, Berman JW, Schwarz M, Demopoulos L, Bijou R, et al. Pathophysiological correlates of increased serum tumor necrosis factor in patients with congestive heart failure. Relation to nitric oxide-dependent vasodilation in the forearm circulation. Circulation. 1994;90(1):12–16. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hurlimann D, Forster A, Noll G, Enseleit F, Chenevard R, Distler O, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha treatment improves endothelial function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2002;106(17):2184–2187. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000037521.71373.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chia S, Qadan M, Newton R, Ludlam CA, Fox KA, Newby DE. Intra-arterial tumor necrosis factor-alpha impairs endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and stimulates local tissue plasminogen activator release in humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(4):695–701. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000065195.22904.FA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yudkin JS, Stehouwer CD, Emeis JJ, Coppack SW. C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: associations with obesity, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction: a potential role for cytokines originating from adipose tissue? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(4):972–978. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.4.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Esposito K, Pontillo A, Di Palo C, Giugliano G, Masella M, Marfella R, et al. Effect of weight loss and lifestyle changes on vascular inflammatory markers in obese women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1799–1804. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cesari M, Penninx BW, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas BJ, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Inflammatory markers and onset of cardiovascular events: results from the Health ABC study. Circulation. 2003;108(19):2317–2322. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097109.90783.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pai JK, Pischon T, Ma J, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, Joshipura K, et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(25):2599–2610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rossouw JE, Siscovick DS, Mouton CP, Rifai N, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers, hormone replacement therapy, and incident coronary heart disease: prospective analysis from the Women's Health Initiative observational study. JAMA. 2002;288(8):980–987. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.8.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Park Y, Capobianco S, Gao X, Falck JR, Dellsperger KC, Zhang C. Role of EDHF in type 2 diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(5):H1982–H1988. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01261.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Vita JA, Keaney JF, Jr, Larson MG, Keyes MJ, Massaro JM, Lipinska I, et al. Brachial artery vasodilator function and systemic inflammation in the Framingham Offspring Study. Circulation. 2004;110(23):3604–3609. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148821.97162.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lee KW, Blann AD, Lip GY. Inter-relationships of indices of endothelial damage/dysfunction [circulating endothelial cells, von Willebrand factor and flow-mediated dilatation] to tissue factor and interleukin-6 in acute coronary syndromes. Int J Cardiol. 2006;111(2):302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]