Abstract

Objective

To determine whether a brief intervention for children with functional abdominal pain and their parents' responses to their child's pain resulted in improved coping 12 months later.

Design

Prospective, randomized, longitudinal study.

Setting

Families were recruited during a 4-year period in Seattle, WA and Morristown, NJ.

Participants

200 children with persistent functional abdominal pain and their parents.

Interventions

A 3-session social learning and cognitive behavioral therapy intervention or an education and support intervention.

Main outcome measures

Child symptoms and pain coping responses were monitored using standard instruments, as was parental response to child pain behavior. Data were collected at baseline and after treatment (1 week and 3, 6, and 12 months after treatment). This article reports the 12-month data.

Results

Relative to children in the education and support group, children in the social learning and cognitive behavioral therapy group reported greater baseline to 12-month follow-up decreases in gastrointestinal symptom severity (estimated mean difference = -0.36, CI = -0.63, -0.01) and greater improvements in pain coping responses (estimated mean difference = 0.61, CI = 0.26, 1.02). Relative to parents in the education and support group, parents in the social learning and cognitive behavioral therapy group reported greater baseline to 12-month decreases in solicitous responses to their child's symptoms (estimated mean difference = -0.22, CI = -0.42, -0.03) and greater decreases in maladaptive beliefs regarding their child's pain (estimated mean difference = -0.36, CI = -0.59, -0.13).

Conclusions

Results suggest long-term efficacy of a brief intervention to reduce parental solicitousness and increasing coping skills. This strategy may be a viable alternative for children with functional abdominal pain.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier #NCT00494260

Long term maintenance of treatment gains is an important goal of any treatment trial. Similarly, ease of administration (i.e., brevity and minimal invasiveness) is also a desirable treatment characteristic, particularly in pediatric practice. However, the demonstration of both of these characteristics often is not present in many studies. The present investigation studied the long term maintenance of beneficial effects achieved in a brief, minimally invasive, intervention for abdominal pain.

Abdominal pain is the most common recurrent pain complaint of childhood, and one often frequently seen by pediatricians.1,2 Organic disease etiology is rarely identified in medical evaluations of childhood abdominal pain, and thus most children with these persistent complaints meet criteria for pediatric functional abdominal pain (FAP). FAP is defined as episodic or continuous abdominal pain without evidence of an inflammatory, anatomicl, metabolic, or neoplastic process that explains the patient's symptoms.3 Children with FAP have increased psychosocial impairment, functional disability, health care utilization, and emotional distress; their parents also report decreased quality of life.4-7 Children with FAP are also at risk for continued symptoms as they age and transition to adulthood,6 and greater risk (in comparison to their well-child peers) for the development of irritable bowel syndrome,8 and chronic pain.9

Study description

We have reported on a prior study that10 tested the efficacy of an intervention (social learning and cognitive behavior therapy [SLCBT]) that (1) taught children and their parents cognitive behavioral strategies for managing the child's symptoms of FAP, and (2) taught parents social learning strategies to reduce solicitous responses to illness behavior in their children and to model and reinforce healthier ways for their children to respond to gastrointestinal discomfort. Social learning theory, and cognitive behavior therapy, a clinical derivative of this theory, maintains that an individual's behavior and thoughts (about physical sensations, pain, or anything) are strongly influenced by the individual's learning history - by the responses the individual has had to prior behavior and thoughts. Prior research4,5,11-21 indicated that a cognitive behavioral approach aimed at changing parental responses to their children's pain might improve the symptoms of FAP. This randomized controlled trial showed that at a six month follow-up, parents in the SLCBT group (relative to those in an education/support [ES] group) reported greater baseline to follow-up reductions in their child's pain, their own solicitous responses to their child's pain reports, and the perceived threat of their child's pain. Children in the SLCBT group, moreover, reported greater baseline to follow-up increases in pain minimization, the ability to distract themselves, and the ability to ignore their pain relative to children in the ES group. Although these findings showed promise, the stability of the outcomes of brief psychosocial interventions such as these over time is an important question that needs to be addressed. Thus, the goal of the present study was to test whether the positive results of this brief intervention would be maintained at a 1-year follow-up. An earlier study reported on data collected through six months, and the present study describes procedures used through the 12-month post-treatment data collection period.

Study Participants

Participants in the randomized controlled trial included 200 FAP parent-child dyads. Families were recruited during a 4-year period via physician referral and community flyers from pediatric gastrointestinal clinics in Seattle, Washington (Seattle Children's Hospital and local area clinics) and Morristown, New Jersey (Atlantic Health System). As noted in the article by Levy et al.,10 eligible children had experienced 3 or more episodes of recurrent abdominal pain during a 3-month period, were 7 to 17 years old, and had cohabited with their parent in the study for the past 5 years or, in cases of divided custody, at least half of the child's lifetime. Exclusion criteria were chronic disease, lactose intolerance, major surgery in the past year, organic evidence of abdominal pain, non-English speaking ability, and developmental disability that impaired the ability to respond.

Design and procedure

The study design was prospective, randomized and longitudinal (NCT00494260). Assessments were completed at baseline and 1 week, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after treatment. Children completed all assessments via telephone with nurse assessors who were masked to treatment assignment. Parents completed all assessments via mail (pencil-and-paper). Randomization followed completion of baseline questionnaires. Patients were stratified into 2 groups based on the child's age at enrollment (7-11 years and 12-17 years).

The 2 conditions consisted of 3 approximately 1-hour, in-person sessions with 1 of 14 trained therapists (master's degree or higher) spaced approximately 1 week apart. During each session, most of the material was covered with children and their parents together, with some time also allotted for each to be seen independently, primarily to allow each to discuss privately any issue they wished. The experimental condition (SLCBT) was based on prior research showing that solicitous responses by parents and parental modeling of illness behavior is associated with more abdominal pain and other gastrointestinal symptoms.16 It was also based on findings that maladaptive beliefs about the significance of pain and coping strategies for dealing with pain have been associated with reported pain and function.22-24 Parents and children were taught ways to think about and cope with pain in ways that encouraged wellness (relaxation and maintenance of regular activities) rather than illness behavior. The second condition (ES), designed to be a time and attention control condition, provided information on the gastrointestinal system and nutrition. Care was taken to include homework assignments, which required similar time and effort as in the SLCBT condition. Further detail can be found in the article by Levy et al.10

Measures completed by parents and children

Faces Pain Scale-Revised (FPS-R25)

The FPS-R consists of 6 hand-drawn faces showing gradual increases in pain expression from left to right. Children are asked to choose the face that best describes their current pain; parents independently make the same rating with respect to their child. Scores can range from 0-10 with higher values indicative of greater pain.

Children's Somatization Inventory (CSI26,27)

The CSI is a reliable and valid measure of children's somatic symptoms. We focused on the 7 items assessing gastrointestinal symptoms: nausea, constipation, loose bowel movements or diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, feeling bloated or gassy, and food making you sick. Children are asked to rate each item with respect to severity during the past week, using a using a 0- to 4-point (not at all to a whole lot) scale. Parents make the same set of ratings with respect to their child's gastrointestinal symptoms.

Measures completed by parents

Demographics

A standard form assessed basic demographic characteristics of both parents and children.

Functional Disability Inventory (FDI28)

The FDI assesses the effect of physical health on children's physical and psychosocial functioning. In the parent-report version, parents are asked to rate the extent to which activities such as “walking to the bathroom” have been difficult or posed a physical challenge for their child during the past week. Ratings are made on a 0- to 4-point (no trouble to impossible) scale.

Adults' Responses to Children's Symptoms (ARCS14,29)

The ARCS assesses parents' self-reported responses to their children's abdominal pain behaviors. We focused on the 15-item protectiveness subscale, a measure of solicitousness or the extent to which parents respond to their children's pain behaviors with sympathy, attention, discouragement of activity, and relief from responsibility. Items such as, “When your child has a stomachache, how often do you tell him/her that s/he doesn't have to finish all of his/her homework?” are rated on a 0- to 4-point (never to always) scale.

Pain Beliefs Questionnaire (PBQ30)

The 32-item PBQ was developed to assess parents' beliefs about various aspects of their child's abdominal pain. Items such as, “My child's stomachaches go on forever” are rated on a 0- to 4-point (not at all true to very true) scale. We focused on the perceived threat subscale, a mean of the condition seriousness, condition duration, condition frequency, episode intensity, and episode duration subscales.

Measures completed by children

Pain Response Inventory (PRI31)

The PRI assesses children's responses to pain. Items such as, “When you have a stomachache, how often do you… think to yourself that it's never going to stop?” are rated on a 0- to 4-point (never to always) scale. The measure includes 13 subscales. We focused on 3 reflective of the SLCBT intervention: catastrophizing, distract/ignore, and minimizing pain.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc). General linear mixed-effects models (GLMMs) for repeated measures data were applied to examine the effects of treatment over time on each of the primary and process-oriented variables. Analyses were performed using an intent- to- treat approach. GLMMs allow for the specification of a covariance structure that accounts for within-subject correlation over time yielding more precise estimates and standard errors. Unlike traditional approaches to analysis of repeated measures that eliminate those with missing data, GLMMs use all available data to generate valid maximum likelihood parameter estimates when the data are assumed to be missing at random. Each repeatedly measured dependent variable was regressed on time, treatment condition, and the interaction of time and treatment, with baseline as the time referent. Child age and sex were included as covariates in the models. The parameter estimates from the interaction terms represent estimates of treatment effects at 12 months (change from baseline to 12 months in the dependent variable in terms of standard deviation units). Maintenance of treatment effects from 6 to 12 months were also calculated and reported. To determine the significance of the 6 contrasts tested for each outcome, we applied the method by Benjamini and Hochberg32 for controlling the false discovery rate at 5%. To quantify the effects of treatment on the outcomes, we calculated the Cohen effect size d. Cohen d reflects the effect of the intervention on the outcome in the scale of standard deviation units, and values are interpreted as low (d = .20), moderate (d = .50), and high (d = .80). A priori power analysis based on a 2-sided independent t test at an uncorrected α of .05 indicated 100 cases per group were required to detect a moderate effect size (Cohen d = .40) with adequate power (1-β = .80).

Although this article reports 6-month to 12-month and baseline to 12-month changes, all data (baseline and 1 week, 3 weeks, 6 months and 12 months after treatment) were included in the model for estimation precision. Given our hypotheses regarding greater improvement in the SLCBT group compared with the ES group, we specified 6 a priori contrasts to be tested using the estimates from each model: within-group change for SLCBT from 6 months to 12 months and baseline to 12 months, within-group change for ES from 6 months to 12 months and baseline to 12 months, and between-group differences in these changes.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the 200 enrolled children were as follows: mean (SD) age, 11.2 (2.6) years; female sex, 72.5%; and white race, 89.0%. Demographic characteristics of parents were as follows: mean (SD) age = 43.7 (6.3) years; female sex, 94.0%; white race, 93.0%; having earned a 4-year college degree, 60.0%; employed full or part time, 68.5%; and married or cohabitating with a partner, 77.0%. These characteristics did not differ as a function of treatment condition (P = .66 for child age, .64 for child sex, .14 for child race, .87 for parent age, .55 for parent sex, .66 for parent race, .98 for parent education, .60 for employment status, and .83 for marital status).

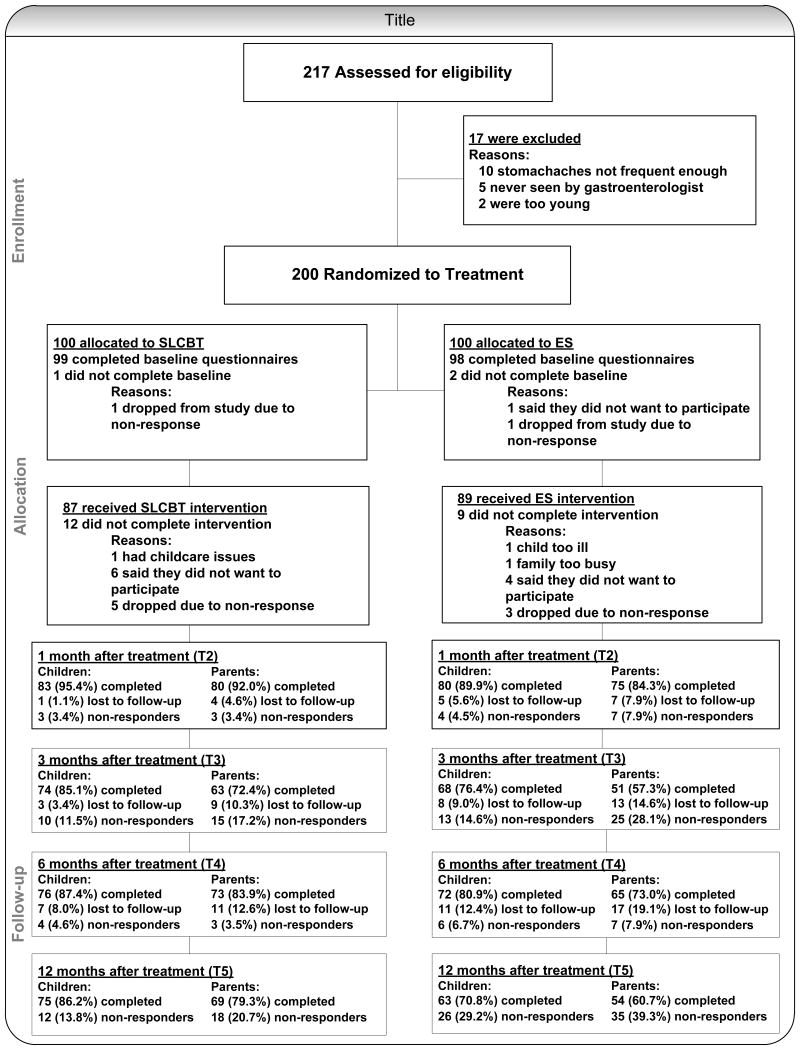

Figure 1 contains a CONSORT diagram illustrating study flow from eligibility assessment to enrollment to intervention and follow-up assessment. A total of 87.0% of SLCBT participants and 89.0% of ES participants completed all 3 intervention sessions (P = .66). Intervention completers and no-completers did not differ with respect to child sex, child age, or child baseline pain levels (P = .50 for sex, .11 for age, and .75 for child pain levels).

Figure 1. Consort Diagram.

Table 1 presents raw means and standard deviations as a function of time (baseline, 6 months, and 12 months) and treatment condition. Table 2 presents results from the GLMMs for the outcome and process variables. Average mean differences with 95% confidence intervals are noted in the following sections and interpreted using Cohen effect size d.

Table 1. Raw means and standard deviations for outcome and process variables as a function of time point and treatment condition.

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 200 | 154 | 141 |

| Parent-report | |||

| Child current pain (FPS-R) | |||

| SLCBT | 2.04 (2.18) | 0.99 (1.82) | 0.88 (1.86) |

| ES | 1.41 (1.91) | 1.35 (2.45) | 0.94 (1.78) |

| Child functional disability (FDI) | |||

| SLCBT | 0.86 (0.77) | 0.42 (0.67) | 0.33 (0.51) |

| ES | 0.81 (0.71) | 0.51 (0.68) | 0.45 (0.63) |

| Child GI symptom severity (CSI) | |||

| SLCBT | 1.25 (0.71) | 0.68 (0.54) | 0.68 (0.63) |

| ES | 1.10 (0.69) | 0.78 (0.66) | 0.81 (0.72) |

| Parental solicitousness (ARCS) | |||

| SLCBT | 1.14 (0.53) | 0.67 (0.52) | 0.57 (0.51) |

| ES | 1.18 (0.57) | 0.96 (0.50) | 0.80 (0.49) |

| Perceived threat (PBQ) | |||

| SLCBT | 2.07 (0.59) | 1.44 (0.67) | 1.41 (0.69) |

| ES | 2.00 (0.53) | 1.73 (0.67) | 1.68 (0.58) |

| Child-report | |||

| Child current pain (FPS-R) | |||

| SLCBT | 2.44 (2.42) | 0.97 (1.40) | 0.93 (1.42) |

| ES | 1.63 (1.85) | 0.74 (1.41) | 0.70 (1.53) |

| Child GI symptom severity (CSI) | |||

| SLCBT | 1.28 (0.75) | 0.70 (0.56) | 0.64 (0.68) |

| ES | 1.09 (0.61) | 0.70 (0.62) | 0.79 (0.71) |

| Catastrophizing (PRI) | |||

| SLCBT | 1.63 (0.86) | 0.99 (0.77) | 0.89 (0.78) |

| ES | 1.56 (0.87) | 1.06 (0.70) | 1.03 (0.76) |

| Distract/Ignore (PRI) | |||

| SLCBT | 2.32 (0.79) | 2.56 (0.67) | 2.61 (0.82) |

| ES | 2.31 (0.81) | 2.44 (0.73) | 2.19 (0.79) |

| Minimizing pain (PRI) | |||

| SLCBT | 1.15 (0.88) | 1.78 (0.88) | 1.84 (0.89) |

| ES | 1.48 (0.90) | 1.57 (0.93) | 1.56 (0.90) |

Note. The SLCBT and ES groups differed at baseline on three measures: parent-reported child current pain (p = .035), child-reported current pain (p = .009), and child-reported minimizing pain (p = .01).

Table 2. Results from repeated measured mixed-effects mixed models examining change from baseline to 12months post-treatment and maintenance of treatment from 6 months to 12 months post-treatment: child age- and gender-adjusted mean changes from baseline (SE) and between-group comparisons.

| 6mo to 12mo change | 95% CI | d | Baseline to 12mo change | 95% CI | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-report | ||||||

| Child current pain (FPS-R) | ||||||

| SLCBT | -0.21 (0.27) | -.74, .31 | -.12 | -1.19 (0.31)* | -1.81, -.58 | -.71 |

| ES | -0.36 (0.30) | -.95, .23 | -.19 | -0.43 (0.33) | -1.08, .23 | -.23 |

| Difference | 0.15 (0.40) | -.65, .94 | .08 | -0.77 (0.46) | -1.66, .13 | -.35 |

| Child functional disability (FDI) | ||||||

| SLCBT | -0.11 (0.09) | -.29, .07 | -.21 | -0.51 (0.11)* | -.72, -.29 | -.89 |

| ES | -0.06 (0.10) | -.26, .14 | -.09 | -0.34 (0.12)* | -.57, -.11 | -.53 |

| Difference | -0.05 (0.13) | -.31, .22 | -.08 | -0.16 (0.16) | -48, .15 | -.22 |

| Child GI symptom severity (CSI) | ||||||

| SLCBT | -0.03 (0.08) | -.18, .12 | -.05 | -0.55 (0.10)* | -.74, -.35 | -.96 |

| ES | 0.04 (0.09) | -.14, .21 | .06 | -0.28 (0.10)* | -.50, -.07 | -.44 |

| Difference | -0.06 (0.12) | -.29, .16 | -.12 | -0.26 (0.15) | -.55, .03 | -.38 |

| Parental solicitousness (ARCS) | ||||||

| SLCBT | -0.13 (0.04)* | -.21, -.04 | -.30 | -0.56 (0.07)* | -.70, -.43 | -1.30 |

| ES | -0.12 (0.05) | -.23, -.01 | -.24 | -0.34 (0.07)* | -.49, -.19 | -.68 |

| Difference | -0.01 (0.07) | -.15, .13 | -.02 | -0.22 (0.10) | -.42, -.03 | -.31 |

| Perceived threat (PBQ) | ||||||

| SLCBT | -0.06 (0.05) | -.16, .04 | -.08 | -0.64 (0.08)* | -.80, -.49 | -.98 |

| ES | -0.02 (0.06) | -.14, .10 | -.03 | -0.28 (0.08)* | -.45, -.12 | -.41 |

| Difference | -0.04 (0.08) | -.19, .12 | -.07 | -0.36 (0.11)* | -.59, -.13 | -.45 |

| Child-report | ||||||

| Child current pain (FPS-R) | ||||||

| SLCBT | -0.04 (0.21) | -.45, .36 | -.02 | -1.50 (0.27)* | -2.02, -.98 | -.77 |

| ES | -0.05 (0.22) | -.49, .39 | -.02 | -0.95 (0.28)* | -1.49, -.40 | -.47 |

| Difference | 0.01 (0.30) | -.59, .60 | .00 | -0.55 (0.38) | -1.31, .20 | -.20 |

| Child GI symptom severity (CSI) | ||||||

| SLCBT | -0.03 (0.07) | -.17, .10 | -.06 | -0.65 (0.09)* | -.83, -.09 | -1.51 |

| ES | 0.11 (0.07) | -.04, .25 | .21 | -0.29 (0.10)* | -.48, -.10 | -.58 |

| Difference | -0.14 (0.10) | -.34, .06 | -.35 | -0.36 (0.13)* | -.63, -.01 | -.53 |

| Catastrophizing (PRI) | ||||||

| SLCBT | -0.11 (0.07) | -.25, .04 | -.11 | -0.76 (0.11)* | -.97, -.54 | -.88 |

| ES | -0.06 (0.08) | -.22, .09 | -.07 | -0.54 (0.11)* | -.76, -.32 | -.63 |

| Difference | -0.04 (0.11) | -.26, .17 | -.07 | -0.21 (0.16) | -.52, .09 | -.20 |

| aDistract/Ignore (PRI) | ||||||

| SLCBT | 0.07 (0.08) | -.09, .23 | .08 | 0.30 (0.11)* | .09, .52 | -.35 |

| ES | -0.20 (0.09) | -.37, -.02 | .23 | -0.08 (0.11) | -.30, .15 | -.09 |

| Difference | 0.26 (0.12) | .03, .50 | .32 | 0.38 (0.16) | .07, .70 | .35 |

| aMinimizing pain (PRI) | ||||||

| SLCBT | 0.07 (0.10) | -.13, .27 | .10 | 0.68 (0.13)* | .45, .98 | 1.11 |

| ES | 0.01 (0.11) | -.21, .22 | .00 | 0.07 (0.14) | -.20, .34 | .11 |

| Difference | 0.06 (0.14) | -.23, .36 | -.07 | 0.61 (0.19)* | .26, 1.02 | .45 |

Estimated mean differences, 95% confidence intervals, and effect size (Cohen's d) from repeated measures mixed-effects models examining change over time from baseline to 12 months and maintenance of effects for 6 months to 12 months, within each treatment group and between treatment group (ES/SLCBT) differences in change over time. To determine significance of the 6 contrasts tested for each outcome (denoted by an asterisk in the table), we applied Benjamini and Hochberg's32 method for controlling false discovery rate at 5%. SLCBT = social learning and cognitive behavioral therapy; ES = education and support.

For these two variables, a positively signed value indicates improvement. For all other variables, a negatively signed value indicates improvement.

Primary outcomes

Pain

As reported in the article by Levy et al.,10 parents in the SLCBT group reported greater reductions in their child's pain from baseline to 6 months relative to parents in the ES group. The present analysis shows that this effect was maintained to 12 months in that parents in the SLCBT condition reported a significant and moderate reduction in their child's pain from baseline to 12 months (average mean difference and 95% confidence interval = -1.19 (-1.81, -.58)), while parents in the ES condition evidenced little change over time, -.43 (-1.08, .23). Overall, the between-group effect was small, -.77 (-1.66, .13). Children in both treatment conditions reported significant within-group baseline to 12 month improvement in self-reported pain, -1.50 (-2.02, -.98) for SLCBT and -.95 (-1.49, -.40) for ES; as with parent-report, the between-group effects were small, -.55 (-1.31, .20) and did not attain significance.

Functional disability

Functional disability as reported by parents significantly decreased (improved) from baseline to 12 months in both treatment conditions, parallel to the 6-month findings10, -.51, (-.72, -.29) for SLCBT, a large effect, and -.34 (-.57, -.11) for ES, a moderate effect; the between-group effect was not significant, -.16 (-.48, .15).

GI symptom severity

Parents' ratings of their child's GI symptoms significantly improved from baseline to 12 month-follow-up in both treatment groups, -.55 (-.74, -.35) for SLCBT and -.28 (-.50,-.07) for ES. The between-group effect size difference was small to moderate -.26 (-.55, .03) and did not reach statistical significance. Children's ratings of their own GI symptoms also improved from baseline to 12 months in both groups, but with significantly greater improvement among children in the SLCBT condition (-.65 (-.83,-.09) for SLCBT, a large effect; -.29 (-.48,-.10) for ES, a moderate effect; and -.36 (-.63, -.01) for the mean difference between groups).

Process variables

Parental solicitousness

As predicted, parents in the SLCBT condition reported greater baseline to 12 month reductions in solicitousness as compared to parents in the ES condition, -.56 (-.70,-.43) for SLCBT and -.34 (-.49,-.19) for ES. The between-group difference was small, -.22 (-.42, -.03). As seen in Table 2, this represents a further reduction in solicitousness from 6 to 12 months in the SLCBT condition.

Pain beliefs

Parallel to the 6 month findings,10 parents in the SLCBT condition reported significantly greater baseline to 12 month reductions in the perceived threat of their child's pain, -.64 (-.80,-.49), a large effect relative to parents in the ES condition, -.28 (-.45,-.12), a small-moderate effect. The between-group effect size difference was significant and moderate, -.36 (-.59, -.13).

Coping skills

Children in the SLCBT condition reported significantly greater baseline to 12 month follow-up increases in the ability to minimize their pain relative to children in the ES condition; .68 (.45, .98) for SLCBT and .07 (-.20, .34) for ES, with a moderate between-group difference, .61 (.26, 1.02). Findings were similar for the ability to distract oneself and ignore the pain; .30 (.09, .52) for SLCBT, -.08 (-.30, .15) for ES, and .38 (.07, .70) for the between-group effect size difference. Catastrophizing lessened/improved over time in both groups; -.76 (-.97, -.54) for SLCBT and -.54 (-.76, -.32) for ES; the difference between groups was small, -.21 (-.52, .09).

Comment

This study demonstrated that after a twelve month follow-up period, children in the cognitive behavioral condition (SLCBT) evidenced greater baseline to 12 month follow-up decreases in gastrointestinal (GI) symptom severity and greater improvements in pain coping responses than children randomly assigned to a comparison condition which controlled for time and attention. Similarly, parents in the cognitive behavioral condition reported greater baseline to 12 month decreases in solicitous responses to their child's symptoms, and greater decreases in maladaptive beliefs regarding their child's pain than parents who were randomly assigned to the time and attention comparison condition. Thus the SLCBT condition continued to demonstrate significant improvements over the ES condition in several key variables.

There are a number of questions which would be logical next steps to address in subsequent research. Certainly one direction worth exploring would be to determine whether the effects of the intervention could be strengthened. An intervention of longer duration, or one with booster sessions, might produce stronger effects. However, this line of exploration should strive to maintain a primary goal of brief intervention research: to develop strategies that are cost-effective and easily implemented in most clinical settings. Another option might consider using this model in a small group setting to make it more cost effective. Further research should thus identify strategies that optimally balance efficacy of therapy with minimizing costs and resource utilization. Relatedly, it would be worthwhile to assess economic and other benefits of the intervention, including fewer missed parent work days or lowered health care utilization. Another important line of investigation worth pursuing would be to identify, and then target, the most active components of the intervention. One possibility is that several of the process variables such as parental solicitousness, pain beliefs, and coping skills mediated changed in child outcome variables. It would be of interest, for example, to isolate the effects of changing parental responses from those of changing child coping or cognitions. Once identified, focusing treatment on the most potent strategies could help improve both efficacy and efficiency of interventions. Relatedly, some research has found both a link between functional abdominal pain and anxiety,33 as well as evidence for the effectiveness of CBT in treating childhood anxiety.33 Therefore, examining and perhaps focusing on anxiety among these functional abdominal pain patients might be one worthwhile direction for this line of research.

Limitations

Despite every effort at randomization, pre-treatment differences were observed for child- and parent-reported child pain. Accordingly, significant magnitude of effect size change for the SLCBT group on these measures needs to be considered in light of potential regression to the mean. Because the analysis was focused on magnitude of improvement from baseline and we only had one baseline assessment, baseline differences were not “controlled for” in the statistical model. Future studies should obtain two baseline assessments to covary out any pretreatment differences while still examining change from baseline. Additionally, participants assigned to the interventions should be stratified on these pain measures.34,35

Conclusions

This study is the largest, to date, randomized controlled trial with a lengthy follow-up period of a psychological intervention for children with functional abdominal pain. It demonstrates maintenance of treatment gains on a number of outcome measures for at least 12 months following a very brief intervention (three sessions) for childhood functional abdominal pain. The data from this study provide some evidence for pediatricians to utilize in beginning to “make the case” to parents about the importance of psychological factors. Further research in this area may help strengthen this case. Nevertheless, for the present, given the relative low cost of this intervention, pediatricians should consider the incorporation of these strategies into their treatment plan for children with this common complaint. The opportunity that some pediatric practices have to co-locate a mental health specialist in an office or clinic may also facilitate making this therapy more available.

References

- 1.McGrath PA. Pain in Children: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: Guilford; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwille IJD, Giel KE, Zipfel S, Enck P, Ellert U. A community-based survey of abdominal pain prevalence, characteristics, and health care use among children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(10):1062–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman DA. Rome III : The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. McLean, Va.: Degnon Associates; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campo JV, Bridge J, Lucas A, et al. Physical and emotional health of mothers of youth with functional abdominal pain. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(2):131–137. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campo JV, Bridge J, Ehmann M, et al. Recurrent abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):817–824. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Lorenzo C, Colletti RB, Lehmann HP, et al. Chronic Abdominal Pain In Children: a Technical Report of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenter Nutr. 2005;40(3):249–261. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000154661.39488.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wendland M, Jackson Y, Stokes LD. Functional disability in paediatric patients with recurrent abdominal pain. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36(4):516–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell S, Poulton R, Talley NJ. The natural history of childhood abdominal pain and its association with adult irritable bowel syndrome: Birth-cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(9):2071–2078. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker LS, Dengler-Crish CM, Rippel S, Bruehl S. Functional abdominal pain in childhood and adolescence increases risk for chronic pain in adulthood. Pain. 2010;150(3):568–572. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy RL, Langer SL, Walker LS, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for children with functional abdominal pain and their parents decreases pain and other symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(4):946–956. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy RL, Langer SL, Walker LS, Feld LD, Whitehead WE. Relationship between the decision to take a child to the clinic for abdominal pain and maternal psychological distress. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(9):961–965. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramchandani PG, Hotopf M, Sandhu B, Stein A. The epidemiology of recurrent abdominal pain from 2 to 6 years of age: Results of a large, population-based study. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):46–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramchandani PG, Stein A, Hotopf M, Wiles NJ. Early parental and child predictors of recurrent abdominal pain at school age: Results of a large population-based study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(6):729–736. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000215329.35928.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Slyke DA, Walker LS. Mothers' responses to children's pain. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(4):387–391. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000205257.80044.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker LS, Williams SE, Smith CA, Garber J, Van Slyke DA, Lipani TA. Parent attention versus distraction: impact on symptom complaints by children with and without chronic functional abdominal pain. Pain. 2006 May;122(1-2):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, et al. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: Effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(12):2442–2451. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duarte MA, Penna FJ, Andrade EM, Cancela CS, Neto JC, Barbosa TF. Treatment of nonorganic recurrent abdominal pain: Cognitive-behavioral family intervention. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43(1):59–64. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000226373.10871.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphreys PA, Gevirtz RN. Treatment of recurrent abdominal pain: Components analysis of four treatment protocols. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31(1):47–51. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palermo TM, Wilson AC, Lewandowski A, Peters M, Somhegyi H. Randomized controlled trial of an internet-delivered family cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain. 2009;146(1-2):205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robins PM, Smith SM, Glutting JJ, Bishop CT. A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral family intervention for pediatric recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(5):397–408. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, McGrath PJ. Online psychological treatment for pediatric recurrent pain: a randomized evaluation. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(7):724–736. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caes L, Vervoort T, Eccleston C, Vandenhende M, Goubert L. Parental catastrophizing about child's pain and its relationship with activity restriction: the mediating role of parental distress. Pain. 2011;152(1):212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goubert L, Vervoort T, Cano A, Crombez G. Catastrophizing about their children's pain is related to higher parent-child congruency in pain ratings: an experimental investigation. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(2):196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hechler T, Vervoort T, Hamann M, Tietze AL, Vocks S, Goubert L. Parental catastrophizing about their child's chronic pain: are mothers and fathers different? Eur J Pain. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.09.015. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The Faces Pain Scale - Revised: Toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93(2):173–183. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garber J, Walker LS, Zeman J. Somatization symptoms in a community sample of children and adolescents: Further validation of the children's somatization inventory. Psychol Assess. 1991;3:588–595. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker LS, Greene JW. Children with recurrent abdominal pain and their parents: More somatic complaints, anxiety, and depression than other patient families? J Pediatr Psychol. 1989;14(2):231–243. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/14.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker LS, Greene JW. The Functional Disability Inventory: Measuring a neglected dimension of child health status. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991 Feb;16(1):39–58. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/16.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker LS, Levy RL, Whitehead WE. Validation of a measure of protective parent responses to children's pain. The Clinical journal of pain. 2006 Oct;22(8):712–716. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210916.18536.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker LS, Smith CA, Garber J, Claar RL. Testing a model of pain appraisal and coping in children with chronic abdominal pain. Health Psychol. 2005;24(4):364–374. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker LS, Smith CA, Garber J, Van Slyke DA. Development and validation of the Pain Response Inventory for Children. Psychol Assess. 1997;9(4):392–405. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nixon RDV, Sterk J, Pearce A. A Randomized trial of cognitive behaviour therapy and cognitive therapy for children with posttraumatic stress disorder following single-incident trauma. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40(3):327–337. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahn C, Tonidandel S, Overall JE. Issues in use of SAS PROC.MIXED to test the significance of treatment effects in controlled clinical trials. J Biopharm Stat. 2000;10(2):265–286. doi: 10.1081/BIP-100101026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senn S. Testing for baseline balance in clinical trials. Stat Med. 1994;13(17):1715–1726. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]