Abstract

Long-term exposure of ethanol (EtOH) alters the structure and function in brain and spinal cord. The present study addresses the mechanisms of EtOH-induced damaging effects on spinal motoneurons in vitro. Altered morphology and biochemical changes of such damage were demonstrated by in situ Wright staining and DNA ladder assay. EtOH at low to moderate (25–50 mM) concentrations induced damaging effects in the motoneuronal scaffold which involved activation of proteases like μ-calpain and caspase-3. Caspase-8 was seen only at higher (100 mM) EtOH concentration. Further, pretreatment with calpeptin, a potent calpain inhibitor, confirmed the involvement of active proteases in EtOH-induced damage to motoneurons. The lysosomal enzyme cathepsin D was also elevated in the motoneurons by EtOH, and this effect was significantly attenuated by inhibitor treatment. Overall, EtOH exposure rendered spinal motoneurons vulnerable to damage, and calpeptin provided protection, suggesting a critical role of calpain activation in EtOH-induced alterations in spinal motoneurons.

Keywords: μ-calpain, calpeptin, caspase-3, caspase-8, cathepsin D, neuroprotection

1 Introduction

Ethyl alcohol (Ethanol; EtOH) has been shown to alter both structure and function in brain and spinal cord. Several studies have shown spinal motoneurons are vulnerable to EtOH, with much of the evidence coming from studies involving following prenatal exposure to the drug [1–4]. EtOH exposure to rat spinal cord slices (postnatal day 1–4) substantially reduced the ability to generate action potentials and synaptic excitation, resulting in increased ratio of inhibitory-to-excitatory spontaneous synaptic currents [5]. In visually identified motor neurons in spinal cord slices from day 14–23 old rats, EtOH exerted direct depressant effects on both AMPA and NMDA glutamate currents without enhancement of GABA or glycine inhibition [6]. While low EtOH concentrations exert temporal and reversible effects, higher concentrations are harmful and toxic to neuronal cells. Nonetheless, information on the effects of EtOH on mature spinal motoneurons is scant.

Ventral spinal cord cells (VSC 4.1 clone) are hybrid cells that can be differentiated into spinal motoneurons with induction of choline acetyltransferase, neuron-specific enolase, neurofilament protein heavy, and synaptophysin, which characterize these cells as viable mammalian motoneurons [7,8]. These cells were originally designed to elucidate mechanisms of motoneuronal degeneration in amyotropic lateral sclerosis [9,7,10,11,8]; however, they have also been widely investigated following glutamate toxicity [12,13], inflammatory stress [14,15], oxidative stress [14,16], amyloid toxicity [17], copper toxicity [18], and proteolytic activation [19]. Accordingly, these cells were chosen to model EtOH-induced proteolytic damage in mature motoneurons.

Calpains, the calcium-dependent cysteine proteases, are a group of non-degradative enzymes, causing limited proteolysis of the target proteins in response to calcium signaling [20]. While calpains serve essential physiological roles, including signal transduction, cell migration, membrane fusion, and cell differentiation, over-activation of calpain contributes to neurodegeneration [21]. Calpains 1 and 2, the two most abundant members of this family in mammals, are heterodimers comprised of an isoform-specific 80 kDa large catalytic subunit and a common 28 kDa small regulatory subunit. Upon binding to Ca2+ via well-conserved amino acids, activation of calpain results in the fusion of two core domains to form the functional protease; different calpain isoforms function through the same mechanism but are regulated independently [22].

Although our key focus was the proteolysis induced by the neutral proteases, the lysosomal enzyme cathepsin D was also investigated as there are conflicting opinions about the involvement of lysosomal proteases following EtOH-exposure [23,24]. As EtOH exposure causes inflammation and both calpain and cathepsin D activation, which are known to cause cell death, may be involved in the motoneuronal damage, as shown earlier in cells undergoing secondary inflammation [25,26].

Inhibition of calpain over-activation is protective against neuroinflammation [27,28], neurodegeneration [29–31], and neurotrauma [32–34]. The current study examined the protective capacity of a potent inhibitor of calpain, calpeptin, against EtOH-induced damage in spinal motoneurons. Our studies demonstrated the vulnerability of motoneurons to EtOH and the induced damage was attenuated by calpeptin for possible recovery of function.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell culture and treatments

The hybrid motoneuron-neuroblastoma cells (VSC 4.1), a gift from Dr. Stanley H. Appel (Huston, Texas, USA), were cultured and differentiated as previously described [19]. Briefly, cells were grown in poly-L-ornithine pre-coated flasks using Dulbecco’s modified Earle’s medium (DMEM)/Ham’s F12 50/50 mix with L-glutamine and 15 mM HEPES (Cellgro, Mediatech, VA, USA) supplemented with penicillin (100 IU/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), 2% Sato’s components, and 2% of heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. Cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. At 60–70% of confluence, cells were sub-cultured and differentiated with dibutyryl cAMP (0.5 mM) over 5–7 days. Bystander killing was attained with aphidicolin (0.4 μg/ml) on every alternative day. Cultured cells were exposed to EtOH (absolute 200 proof, AAPER Alcohol, KY, USA) via low-serum (0.5% FBS) containing medium to attain low (12.5–25 mM), medium (50 mM), or high (100–200 mM) concentrations of EtOH. The cells were collected after 6 h or 24 h of exposure, with respective controls included at corresponding time points. Next, to test cytoprotection, cells were pretreated with three concentrations (100 nM, 1 and 5 μM) of the inhibitor calpeptin (EMD Biosciences, NJ, USA), 1 h prior to EtOH exposure.

2.2 In situ Wright staining

VSC 4.1 cells were cultured and differentiated in 6-well plates with cover slips inserted. Cells were exposed to a single concentration of EtOH (12.5–200 mM) in each plate for 6 or 24 h. Plates were centrifuged to sediment the non-adherent cells. Wright staining was performed as previously described [19], and images were captured at 200x magnification.

2.3 DNA ladder assay

Genomic DNA was isolated using Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, MI, USA) following manufacturer’s protocol as previously described [19]. DNA samples were resolved at 80 V for 1 h in 1% agarose gel with reference to 100 bp DNA standard ladder. The gel was subsequently stained with SYBR® Safe (Molecular Probes, USA), and DNA fragments were visualized in Alpha Innotech FluorChem FC2 Imager with UV transillumination and captured at the green filter position.

2.4 Western blot

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described [19]. Briefly, control and EtOH-exposed cells were harvested, and pellets were homogenized by sonication in homogenizing buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, (pH 7.4) with 5 mM EGTA, and freshly added 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride]. Samples were diluted 1:1 in sample buffer [62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol] and boiled. Protein concentration was adjusted to a concentration of 1.5 mg/mL with 1:1 v/v mix of homogenizing buffer and sample buffer containing 0.01% bromophenol blue. Samples were resolved in 4–20% or 7.5% (for SBDP) of precast sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA) at 100 V for 1 h, transferred to the Immobilon™- polyvinylidene fluoride microporous membranes (Millipore, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-HCl buffer (0.1% Tween-20 in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6). Following overnight incubation at 4°C with appropriate primary IgG antibodies, blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated corresponding secondary IgG antibodies at room temperature. Between incubations, membranes were washed 3 × 5 min in Tris-HCl buffer. Immunoreactive protein bands were detected with chemiluminescent reagent and images were acquired using Alpha Innotech FluorChem FC2 Imager.

Antibodies used in the study included rabbit polyclonal anti-caspase-3, anti-caspase-8, and anti-cathepsin D, mouse monoclonal anti-Bax and anti-Bcl-2 (all diluted 1:250; Santa Cruz, CA, USA); mouse monoclonal anti α-Fodrin (αII-spectrin, 1:10,000; Biomol International, PA, USA); rabbit polyclonal anti-μ-calpain (1:500; [35]). The bound antibodies were visualized by corresponding peroxidase-conjugated IgG antibodies (1:2000; MP Biomedicals, OH, USA).

2.5 Immunocytofluorescent staining

Cells were processed as in Wright staining, fixed with 95% EtOH for 10 min followed by two consecutive rinses with PBS, and blocked with goat serum in PBS for 1 h (all procedures were done in wells). Cover slips with cells were removed from wells, placed on glass microscope slides, and incubated with active μ-calpain antibody (1:1000) overnight at 4°C. Immunostaining was visualized with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary IgG (green); cell nuclei were counterstained and finally mounted with antifade Vectashield™ (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA). Fluorescent images were viewed and captured in Olympus BH-2 microscope at 200x magnification.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Each assay was performed in triplicate and the experiment was repeated twice. Optical density (OD) of protein immunoreactivity (IR) bands obtained from Western blotting was analyzed with NIH ImageJ 1.45 software. Results were assessed in Stat View software (Abacus Concepts, CA, USA) and compared by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s protected least significant difference (PLSD) post hoc test at 95% confidence interval. The difference was considered significant at p ≤ 0.05. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM (n ≥ 3). EtOH-induced changes in levels of protein (%) were considered significant at *p ≤ 0.05, compared to control, and @p ≤0.05, compared to calpeptin pretreatment.

Results

3.1 Morphological and biochemical alterations in motoneurons induced by EtOH

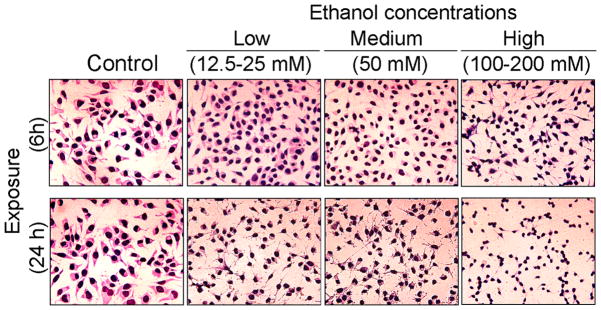

EtOH exposure induced morphological and biochemical alterations in motoneurons, which were assessed with Wright staining and DNA ladder assay, respectively. Microscopic observation of stained cells showed visible morphological changes in motoneurons in response to EtOH exposure compared to control cells (Figure 1). The viability of motoneurons strongly depended on EtOH concentration and time of exposure. Short term (6 h) exposure reduced the cell size and shortened the processes, whereas, long term (24 h) exposure caused visible morphological changes even at lower concentrations of EtOH (12.5–25 mM). The damaging effects were aggravated with increasing concentrations of EtOH. The most severe damage to these cells was observed with the highest concentrations of EtOH (100–200 mM) following 24 h exposure. Despite obvious morphological alterations with EtOH exposure at all concentrations and time-points tested, there was no significant motoneuronal death as detected by MTT assay.

Figure 1.

EtOH-induced morphological change in motoneurons. Representative images of EtOH-exposed motoneurons illustrate morphological changes in motoneurons proportional to time and concentration of EtOH exposure. Compared to the healthy control motoneurons, EtOH-exposed cells have reduced sizes, shortened processes, and condensed cytoplasm. EtOH exposure caused clumping of motoneuronal cells, which was more prominently seen in lower doses. Images were taken at 200x magnification.

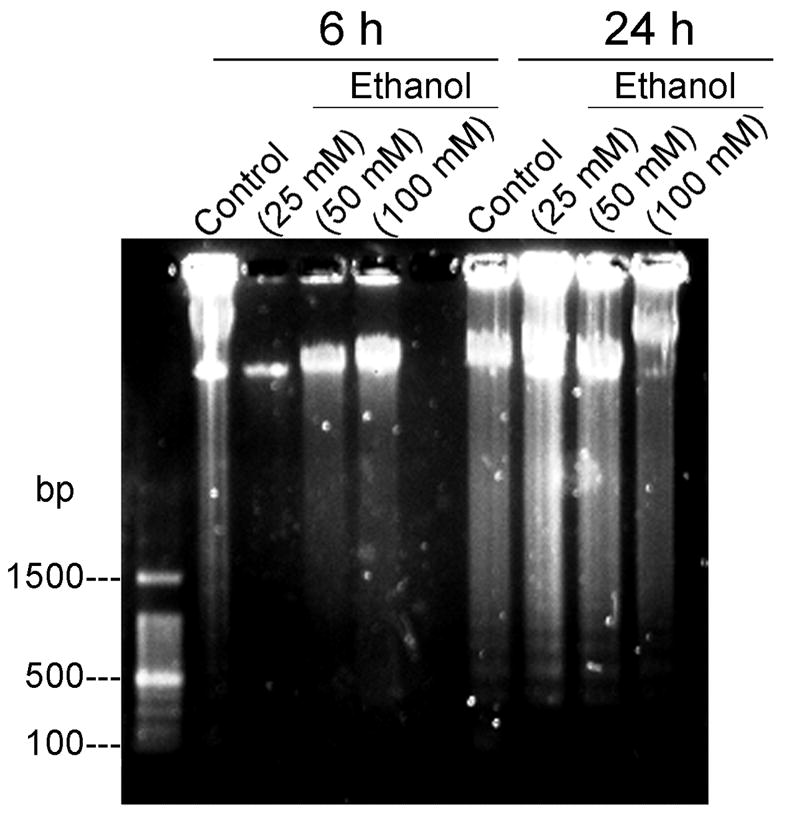

DNA electrophoresis revealed biochemical changes in EtOH-exposed motoneurons compared to control cells (Figure 2). DNA fragmentation was not seen in either control cells or cells exposed to EtOH for 6 h, but occurred significantly at 24 h of exposure to 25, 50, or 100 mM EtOH. DNA laddering was also faintly shown in control cells after 24 h, which can be explained by possible fragmentation of DNA at low serum concentration in the treatment medium.

Figure 2.

EtOH-induced fragmentation of motoneuronal DNA. Representative images of motoneuronal cell genomic DNA gel stained by SYBR® safe via UV-transillumination demonstrate that only long time exposure (24 h) to EtOH (25, 50 and 100 mM) induced DNA laddering in motoneurons. Some DNA fragmentation was also visible at 24 h in control cells, probably due to spontaneous moderate destruction of DNA in low serum medium.

3.2 EtOH activates calpain in motoneurons

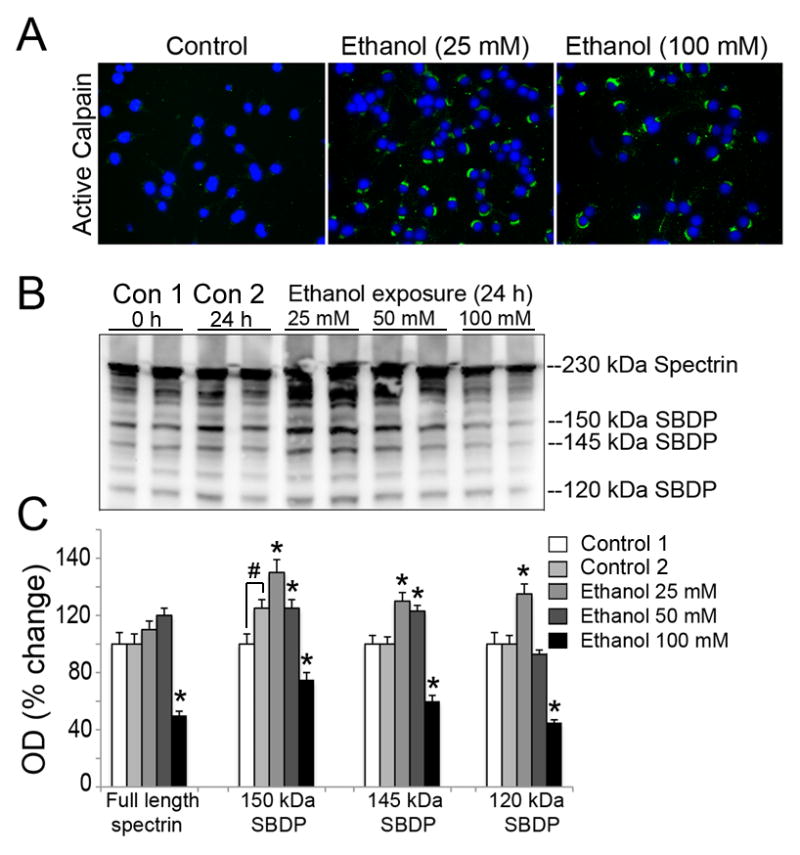

While EtOH is known to increase intracellular Ca2+ levels in cultured cells [36], chronic EtOH exposure has been found to upregulate calpain in rat brain [37]. In the present study, we have investigated whether EtOH-induced morphological and biochemical alterations were driven by over-activation of calpain in motoneurons. Following EtOH exposure, the activation of μ-calpain in motoneurons was evaluated by immunocytofluorescent staining and by formation of SBDP from spectrin via Western blot. Control 1 represented the terminally differentiated motoneurons which were collected at 0 h and were always maintained in 2% FBS. However, Control 2 comprised of the cells that were incubated in reduced serum condition (0.5%) parallel to those being exposed to EtOH for 24 h. Terminally differentiated motoneurons showed some alterations under reduced serum condition (Control 2), in present study we found significantly increased levels of 150 kDa SBDP (Figure 3). All EtOH-exposed cells were compared to ‘Control 2’ in Figure 3. Compared to control, active μ-calpain-IR was significantly induced in motoneurons by relatively low EtOH (25 mM) exposure, and elevated levels of active μ-calpain were still evident in surviving neurons following exposure to 100 mM EtOH (Figure 3A). The proteolytic activity of calpain and caspase-3 were monitored through cleavage of their substrate spectrin, a cytoskeleton intermediate filament protein, and formation of SBDPs, detected as calpain specific 145 kDa SBDP and caspase-3 specific 120 kDa SBDP bands. SBDP formation was compared in control and EtOH-exposed (25, 50 or 100 mM for 24 h) motoneurons. EtOH at 25 and 50 mM significantly increased calpain specific 150 and 145 kDa SBDPs while 25 mM EtOH provoked increase in caspase-3 specific 120 kDa SBDP, as compared to control (*p < 0.05), indicating EtOH-induced activation of calpain and caspase-3 in motoneurons (Figure 3B and C, respectively). High EtOH exposure (100 mM) significantly reduced the parent (230 kDa) spectrin level in motoneurons compared to control (*p < 0.05). The high EtOH concentration (100 mM) was found to further degrade all SBDPs (150, 145 and 120 kDa) compared to low EtOH concentrations (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

EtOH-induced μ-calpain activation in motoneurons. (A) Representative images of active μ-calpain (green) and nuclei counterstained (blue) from three independent experiment (n = 3) illustrate that active μ-calpain IR is significantly increased in motoneuronal cytoplasm after EtOH exposure (a low 25 mM concentration), compared to control cells and remained expressed at 100 mM EtOH in surviving cells. (B) Representative immunoblots and corresponding bar graphs (C) from three independent experiment (n = 3) showing 230 kDa full length αII-spectrin, 150 and 145 kDa calpain specific SBDPs, and 120 kDa caspase-3 specific SBDP. Control 1 represented the differentiated motoneurons collected at 0 h whereas in control 2 motoneurons were incubated in reduced serum condition (0.5%) parallel to those being exposed to EtOH for 24 h. Control 1 and 2 had significantly altered levels of 150 kDa SBDP. All EtOH-exposed cells were compared to ‘Control 2’ in Figure 3. Bar graphs indicate the increase in levels of SBDPs (↑) in motoneurons after EtOH exposure due to calpain and caspase-3 activation. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n ≥ 3; *p ≤ 0.05, significantly different from control 2.

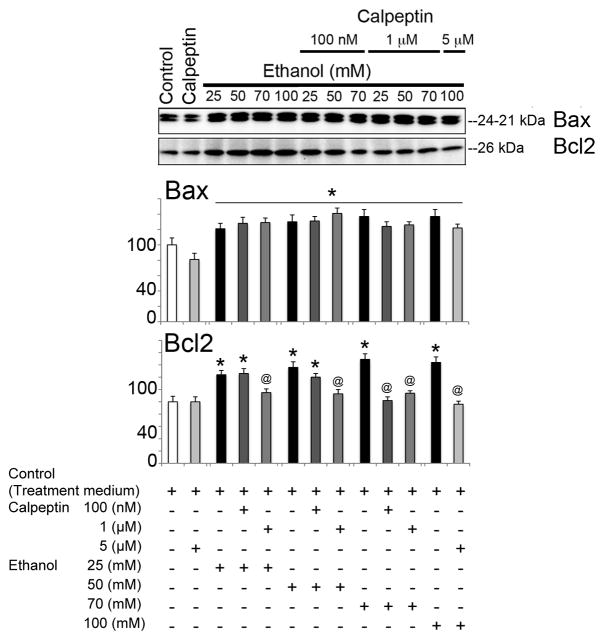

3.3 Calpeptin protects motoneurons against EtOH toxicity

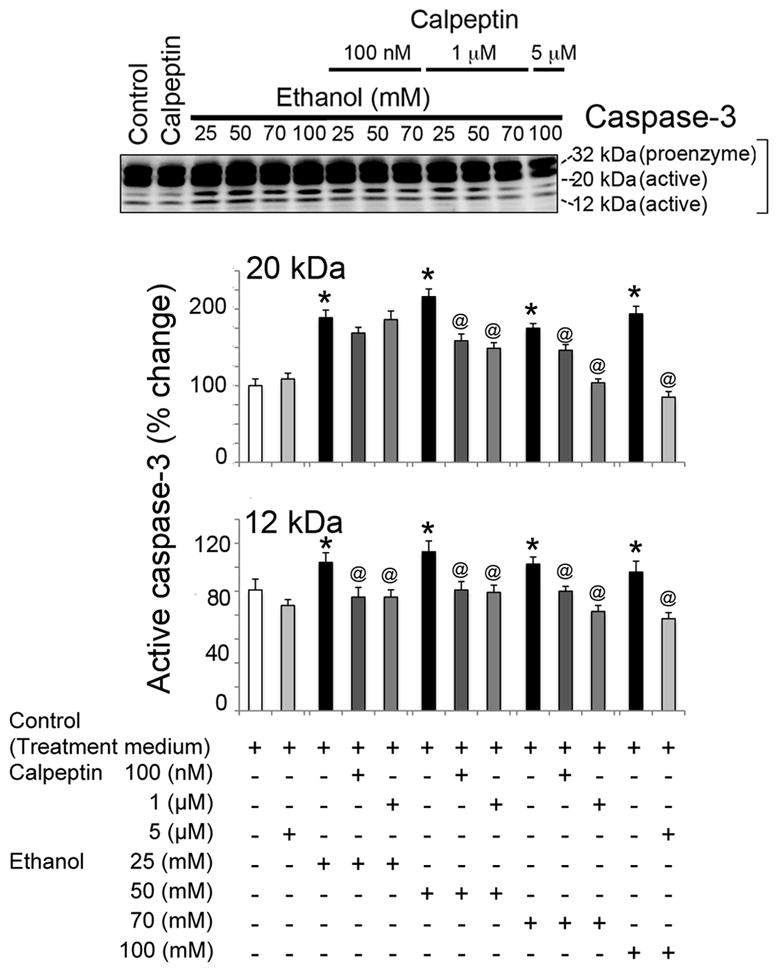

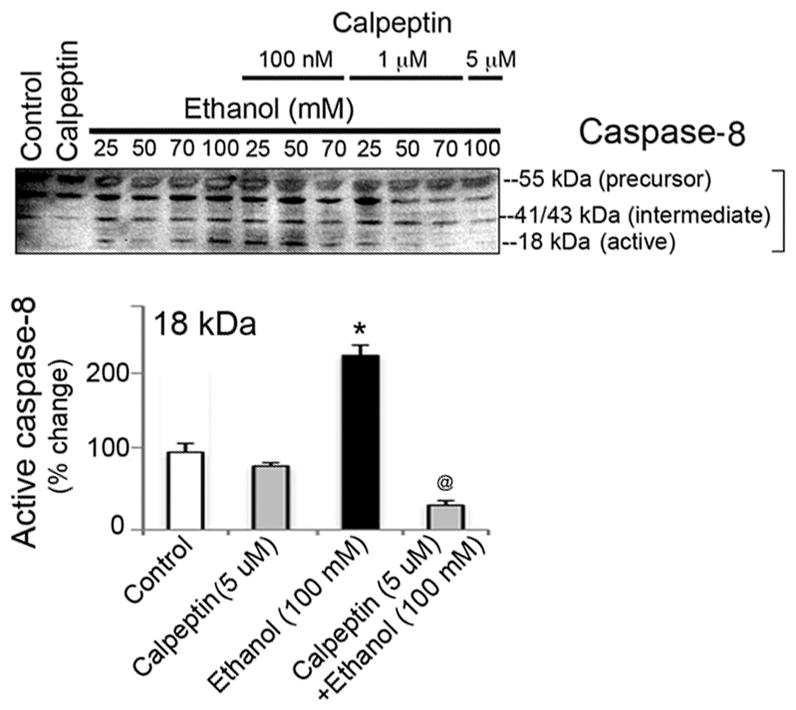

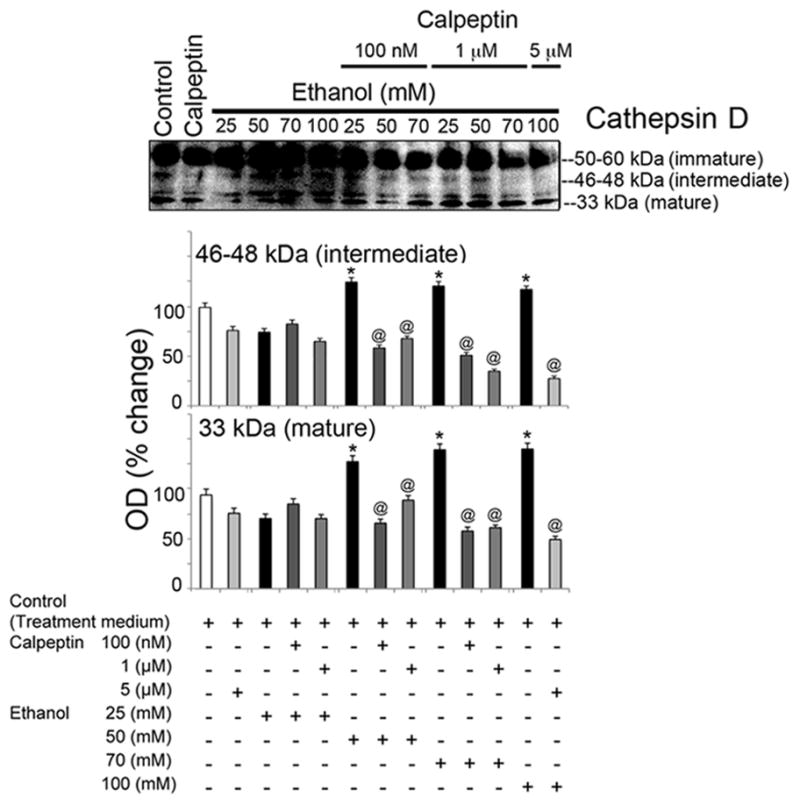

To assess the cytoprotective effects of calpeptin in motoneurons, cells were divided into the following groups: control, calpeptin alone (5 μM), EtOH-exposed (25, 50, 70, or 100 mM), and calpeptin (100 nM, 1 μM, or 5 μM) pretreated prior to EtOH exposure. Total incubation time was set at 24 h. EtOH exposure significantly elevated Baxα (24 kDa) and Baxβ (21 kDa) at all concentrations and even induced Bcl-2 (26 kDa) in motoneurons (Figure 4). Pretreatment with calpeptin had no attenuating effects on Bax levels, but reduced the levels of Bcl-2, suggesting early acute dysregulation of these mitochondrial proteins in motoneurons following EtOH treatment (Figure 4). Active caspase-3 (20 and 12 kDa) bands were found significantly up-regulated in EtOH-exposed motoneurons (Figure 5). The 20 kDa active band was predominant over 12 kDa. All doses of calpeptin (100 nM–5 μM) attenuated EtOH-induced elevation of active caspase-3 bands, irrespective of EtOH concentration, and suggest over-activation of μ-calpain and caspase-3 mediated motoneuron damage (Figure 5). A dose-dependent trend in EtOH effect was seen in the lower (25 to 50 mM) concentration of EtOH which are physiologically more relevant; but, such effects were not further aggravated by the higher toxic EtOH dose of 100 mM. Involvement of caspase-8 in EtOH-exposed motoneurons was seen only following high dose treatment, and calpeptin (5 uM) attenuated this effect (Figure 6). Lysosomal protease cathepsin-D was also upregulated by EtOH. The increased effect was seen from 25 mM to 50 mM and it peaked at 50 mM. However, the important finding is that calpeptin attenuated the increase as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 4.

EtOH-induced dysregulation of Bax and Bcl-2 in motoneurons. Representative immunoblot from three independent experiment (n = 3) showed significant increase in expression of 24 and 21 kDa Bax (↑) after exposure to EtOH compared to control (equivalent to control 2 of experiment 3) (*p≤0.05). Levels of Bcl-2 (↑) were also significantly increased by EtOH (*p ≤ 0.05), resulting in unaltered Bax: Bcl2 ration upon EtOH exposure, as shown in the lower panel. Pretreatment with calpeptin failed to reduce the levels of Bax (↓) (@p ≤ 0.05) but decreased the levels of Bcl-2 (↓) (@p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 5.

Calpeptin mediated protection against active caspase-3 in EtOH-exposed motoneurons. Representative immunoblots and corresponding bar graphs from three independent experiment (n = 3) showed significant activation of caspase-3 (↑), increased levels of 20 kDa and 12 kDa active caspase-3 [*p ≤ 0.05, compared to control (equivalent to control 2 of experiment 3)] in EtOH exposed motoneurons. Calpeptin relatively reduced pro-caspase-3 and significantly diminished active caspase-3 fragments (↓) in motoneurons (@p ≤ 0.05, relative to EtOH). All calpeptin doses were found effective against EtOH.

Figure 6.

Calpeptin mediated protection against active caspase-8 in EtOH-exposed motoneurons. Representative immunoblots of caspase-8 and corresponding bar graphs from three independent experiment (n = 3) indicate significant increase of 18 kDa caspase-8 (↑) by high concentration of EtOH (100 mM), compared to control (equivalent to control 2 of experiment 3) (*p ≤ 0.05). Calpeptin (5 μM) effectively reduced active caspase-8 (↓) in motoneurons (@p ≤ 0.05, relative to EtOH).

Figure 7.

Calpeptin mediated protection against active cathepsin-D in EtOH-exposed motoneurons. Representative immunoblots from three independent experiment (n = 3) and corresponding bar graphs showed significant activation of cathepsin-D (↑), increased levels of intermediate and mature cathepsin-D [*p ≤ 0.05, compared to control(equivalent to control 2 of experiment 3)] in EtOH exposed motoneurons. Calpeptin relatively reduced pro-cathepsin-D and significantly diminished intermediate and mature fragments (↓) in motoneurons (@p ≤ 0.05, relative to EtOH). All calpeptin doses were found effective against EtOH.

Discussion

Results from the present study demonstrated that in vitro EtOH exposure in mature rat spinal motoneurons produced significant morphological alterations, DNA laddering, up-regulation of mitochondrial apoptotic proteins, and activation of cysteine proteases μ-calpain and caspase-3 in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Despite the presence of morphological and biochemical alterations, no significant alterations in EtOH-mediated cell death was discernible by MTT assay, although molecular markers of cell damage (Bax, caspase-3 and calpain activity) were up-regulated. Although EtOH exposure also showed an elevated level of Bcl2, which is an anti-apoptotic mitochondrial protein, the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio was not altered. Whether this is due to compensatory mechanisms triggered following EtOH exposure is not clear at present. Caspase-8, on the other hand, was up-regulated at a higher concentration of EtOH and significantly inhibited by calpeptin, indicating that the caspase-8 mediated cell death pathway is controlled by calpain inhibition.

The damaging effects of EtOH on the central nervous system (CNS) has drawn much attention recently, and EtOH has been found to have profound effects in altering the structure and function of the CNS [38]. A rise in intracellular Ca2+ and subsequent aberrant Ca2+ homeostasis may be one of the mechanisms involved in EtOH-induced damage of the CNS. Indeed, EtOH exposure is capable of inducing a dual effect on intracellular Ca2+ levels in cells, a rise at physiologically relevant concentrations and reduced intracellular Ca2+ levels at higher toxic concentrations [39]. A sustained rise in intracellular Ca2+ is suggested as a key underlying mechanisms for neuronal cell death, as recently reported in cerebellar granular neurons [40]. Thus, death of neurons due to EtOH exposure may affect behavioral as well as motor function. To this end, chelation of intracellular Ca2+ has been recently shown to attenuate EtOH-induced behavioral deficits in mice [41]. Therefore, a rise in intracellular Ca2+ may be conducive to calpain over-activation leading to cell damage/death. In the current study, we report EtOH-induced activation of μ-calpain in spinal motoneurons, which may cause damaging effects leading to motor dysfunction. The calpain inhibitor attenuated many of the EtOH-induced protease-related responses in spinal motoneurons in culture and thereby may have potential protective effects.

In addition to the neutral proteases, EtOH also up-regulated the lysosomal protease cathepsin D. Subjects acutely intoxicated with EtOH were reported to have unaltered activity of cathepsin D, while levels were significantly increased in the chronic alcoholic serum [24]. In contrast, another study reported that lysosomal and nonlysosomal protease activities of the brain remain unaltered in response to EtOH feeding [23]. The current study demonstrated EtOH-induced upregulation of lysosomal cathepsin D and the protective capacity of calpeptin against EtOH-induced cathepsin D expression in spinal motoneurons. Such protective effects of calpeptin against lysosomal cathepsin D were also seen in other cells in culture undergoing inflammatory stress [25]. Thus, attenuation of both calpain activation and cathepsin D upregulation by calpeptin prevents the EtOH induced damage, as demonstrated in the present study and also reported elsewhere [25,26].

In summary, calpain activation in spinal motoneurons is detrimental, as shown in the current study and as previously reported [12,19]. EtOH exposure impaired cultured motoneurons, which was significantly attenuated by calpain inhibition. These in vitro findings on the attenuating effects of calpeptin are being tested in vivo in mice exposed to EtOH.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the R01 grants from National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health (NINDS-NIH; NS-62327-01A2), Veterans Administration (1I01BX001262), Alcohol Research Center (P50AA10716) and the State of South Carolina Spinal Cord Injury Foundation.

Abbreviations

- EtOH

ethanol

- IR

immunoreactivity

- OD

optical density

- SBDP

spectrin breakdown products

- VSC 4.1

ventral spinal cord cells clone 4.1

References

- 1.Barrow Heaton MB, Kidd K, Bradley D, Paiva M, Mitchell J, Walker DW. Prenatal ethanol exposure reduces spinal cord motoneuron number in the fetal rat but does not affect GDNF target tissue protein. Dev Neurosci. 1999;21 (6):444–452. doi: 10.1159/000017412. 17412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley DM, Beaman FD, Moore DB, Heaton MB. Ethanol influences on the chick embryo spinal cord motor system. II. Effects of neuromuscular blockade and period of exposure. J Neurobiol. 1997;32 (7):684–694. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19970620)32:7<684::aid-neu4>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley DM, Beaman FD, Moore DB, Kidd K, Heaton MB. Neurotrophic factors BDNF and GDNF protect embryonic chick spinal cord motoneurons from ethanol neurotoxicity in vivo. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;112 (1):99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heaton MB, Bradley DM. Ethanol influences on the chick embryo spinal cord motor system: analyses of motoneuron cell death, motility, and target trophic factor activity and in vitro analyses of neurotoxicity and trophic factor neuroprotection. J Neurobiol. 1995;26 (1):47–61. doi: 10.1002/neu.480260105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng G, Gao B, Verbny Y, Ziskind-Conhaim L. Ethanol reduces neuronal excitability and excitatory synaptic transmission in the developing rat spinal cord. Brain Res. 1999;845 (2):224–231. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01968-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang MY, Rampil IJ, Kendig JJ. Ethanol directly depresses AMPA and NMDA glutamate currents in spinal cord motor neurons independent of actions on GABAA or glycine receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290 (1):362–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexianu ME, Robbins E, Carswell S, Appel SH. 1Alpha, 25 dihydroxyvitamin D3-dependent up-regulation of calcium-binding proteins in motoneuron cells. J Neurosci Res. 1998;51(1):58–66. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980101)51:1<58::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-K. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith RG, Alexianu ME, Crawford G, Nyormoi O, Stefani E, Appel SH. Cytotoxicity of immunoglobulins from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients on a hybrid motoneuron cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91 (8):3393–3397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexianu ME, Ho BK, Mohamed AH, La Bella V, Smith RG, Appel SH. The role of calcium-binding proteins in selective motoneuron vulnerability in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1994;36 (6):846–858. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Appel SH, Smith RG, Alexianu M, Siklos L, Engelhardt J, Colom LV, Stefani E. Increased intracellular calcium triggered by immune mechanisms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin Neurosci. 1995;3 (6):368–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho BK, Alexianu ME, Colom LV, Mohamed AH, Serrano F, Appel SH. Expression of calbindin-D28K in motoneuron hybrid cells after retroviral infection with calbindin-D28K cDNA prevents amyotrophic lateral sclerosis IgG-mediated cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93 (13):6796–6801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das A, Sribnick EA, Wingrave JM, Del Re AM, Woodward JJ, Appel SH, Banik NL, Ray SK. Calpain activation in apoptosis of ventral spinal cord 4.1 (VSC4.1) motoneurons exposed to glutamate: calpain inhibition provides functional neuroprotection. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81 (4):551–562. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sribnick EA, Del Re AM, Ray SK, Woodward JJ, Banik NL. Estrogen attenuates glutamate-induced cell death by inhibiting Ca2+ influx through L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Brain Res. 2009;1276:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das A, McDowell M, Pava MJ, Smith JA, Reiter RJ, Woodward JJ, Varma AK, Ray SK, Banik NL. The inhibition of apoptosis by melatonin in VSC4.1 motoneurons exposed to oxidative stress, glutamate excitotoxicity, or TNF-alpha toxicity involves membrane melatonin receptors. J Pineal Res. 2010;48 (2):157–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2009.00739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith JA, Zhang R, Varma AK, Das A, Ray SK, Banik NL. Estrogen partially down-regulates PTEN to prevent apoptosis in VSC4.1 motoneurons following exposure to IFN-gamma. Brain Res. 2009;1301:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HJ, Kim M, Kim SH, Sung JJ, Lee KW. Alteration in intracellular calcium homeostasis reduces motor neuronal viability expressing mutated Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase through a nitric oxide/guanylyl cyclase cGMP cascade. Neuroreport. 2002;13 (9):1131–1135. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200207020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han M, Liu Y, Zhang B, Qiao J, Lu W, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Zhao C. Salvianic borneol ester reduces beta-amyloid oligomers and prevents cytotoxicity. Pharm Biol. 49(10):1008–1013. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2011.559585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HJ, Kim JM, Park JH, Sung JJ, Kim M, Lee KW. Pyruvate protects motor neurons expressing mutant superoxide dismutase 1 against copper toxicity. Neuroreport. 2005;16(6):585–589. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200504250-00014. 00001756-200504250-00014 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samantaray S, Knaryan VH, Le Gal C, Ray SK, Banik NL. Calpain inhibition protected spinal cord motoneurons against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion and rotenone. Neuroscience. 2011;192:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell RL, Davies PL. Structure-function relationships in calpains. Biochem J. 447(3):335–351. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120921. BJ20120921 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geddes JW, Saatman KE. Targeting individual calpain isoforms for neuroprotection. Exp Neurol. 226(1):6–7. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.07.025. S0014-4886(10)00263-3 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ono Y, Sorimachi H. Calpains: an elaborate proteolytic system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1824(1):224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.08.005. S1570-9639(11)00231-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonner AB, Swann ME, Marway JS, Heap LC, Preedy VR. Lysosomal and nonlysosomal protease activities of the brain in response to ethanol feeding. Alcohol. 1995;12(6):505–509. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(95)00035-6. 0741832995000356 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaminski J, Kozuchowski D, Borkowski J, Malinowska L. The activity of cathepsin A and cathepsin D in the serum of persons acutely intoxicated with ethanol and chronic alcoholics. Rocz Akad Med Bialymst. 1995;40 (1):209–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nozaki K, Das A, Ray SK, Banik NL. Calpain inhibition attenuates intracellular changes in muscle cells in response to extracellular inflammatory stimulation. Exp Neurol. 225(2):430–435. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.07.021. S0014-4886(10)00259-1 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nozaki K, Das A, Ray SK, Banik NL. Calpeptin attenuated apoptosis and intracellular inflammatory changes in muscle cells. J Neurosci Res. 89(4):536–543. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyton MK, Brahmachari S, Das A, Samantaray S, Inoue J, Azuma M, Ray SK, Banik NL. Inhibition of calpain attenuates encephalitogenicity of MBP-specific T cells. J Neurochem. 2009;110 (6):1895–1907. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06287.x. JNC6287 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guyton MK, Das A, Samantaray S, Wallace GCt, Butler JT, Ray SK, Banik NL. Calpeptin attenuated inflammation, cell death, and axonal damage in animal model of multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Res. 88(11):2398–2408. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crocker SJ, Smith PD, Jackson-Lewis V, Lamba WR, Hayley SP, Grimm E, Callaghan SM, Slack RS, Melloni E, Przedborski S, Robertson GS, Anisman H, Merali Z, Park DS. Inhibition of calpains prevents neuronal and behavioral deficits in an MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23(10):4081–4091. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04081.2003. 23/10/4081 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant RJ, Sellings LH, Crocker SJ, Melloni E, Park DS, Clarke PB. Effects of calpain inhibition on dopaminergic markers and motor function following intrastriatal 6-hydroxydopamine administration in rats. Neuroscience. 2009;158 (2):558–569. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.023. S0306-4522(08)01544-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van den Bosch L, Van Damme P, Vleminckx V, Van Houtte E, Lemmens G, Missiaen L, Callewaert G, Robberecht W. An alpha-mercaptoacrylic acid derivative (PD150606) inhibits selective motor neuron death via inhibition of kainate-induced Ca2+ influx and not via calpain inhibition. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42(5):706–713. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00010-2. S0028390802000102 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bains M, Cebak JE, Gilmer LK, Barnes CC, Thompson SN, Geddes JW, Hall ED. Pharmacological analysis of the cortical neuronal cytoskeletal protective efficacy of the calpain inhibitor SNJ-1945 in a mouse traumatic brain injury model. J Neurochem. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ray SK, Matzelle DD, Sribnick EA, Guyton MK, Wingrave JM, Banik NL. Calpain inhibitor prevented apoptosis and maintained transcription of proteolipid protein and myelin basic protein genes in rat spinal cord injury. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;26(2):119–124. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(03)00044-9. S0891061803000449 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ray SK, Matzelle DD, Wilford GG, Hogan EL, Banik NL. Inhibition of calpain-mediated apoptosis by E-64 d-reduced immediate early gene (IEG) expression and reactive astrogliosis in the lesion and penumbra following spinal cord injury in rats. Brain Res. 2001;916(1–2):115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02874-8. S0006-8993(01)02874-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banik NL, Hogan EL, Jenkins MG, McDonald JK, McAlhaney WW, Sostek MB. Purification of a calcium-activated neutral proteinase from bovine brain. Neurochem Res. 1983;8 (11):1389–1405. doi: 10.1007/BF00964996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belia S, Mannucci R, Lisciarelli M, Cacchio M, Fano G. Double effect of ethanol on intracellular Ca2+ levels in undifferentiated PC12 cells. Cell Signal. 1995;7(4):389–395. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(94)00092-p. 089865689400092P [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajgopal Y, Vemuri MC. Calpain activation and alpha-spectrin cleavage in rat brain by ethanol. Neurosci Lett. 2002;321(3):187–191. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00063-0. S0304394002000630 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evrard S, GaB A. Ethanol Effects on the Cytoskeletal of Nervous Tissue Cells. In: Nixon R, AaY A, editors. Advances in Neurobiology, vol 3. vol Cytoskeleton of the Nervous System. Springer Science; 2011. pp. 697–758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belia S, Mannucci R, Lisciarelli M, Cacchio M, Fano G. Double effect of ethanol on intracellular Ca2+ levels in undifferentiated PC12 cells. Cell Signal. 1995;7 (4):389–395. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(94)00092-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kouzoukas DE, Li G, Takapoo M, Moninger T, Bhalla RC, Pantazis NJ. Intracellular calcium plays a critical role in the alcohol-mediated death of cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurochem. 124(3):323–335. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balino P, Monferrer L, Pastor R, Aragon CM. Intracellular calcium chelation with BAPTA-AM modulates ethanol-induced behavioral effects in mice. Exp Neurol. 2012;234 (2):446–453. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]