Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the spatial correlation between high uptake regions of 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) before and after therapy in recurrent lung cancer.

Methods and Materials

We enrolled 106 patients with inoperable lung cancer into a prospective study whose primary objectives were to determine first, the earliest time point when the maximum decrease in FDG uptake representing the maximum metabolic response (MMR) is attainable and second, the optimum cutoff value of MMR based on its predicted tumor control probability, sensitivity, and specificity. Of those patients, 61 completed the required 4 serial 18F-FDG PET examinations after therapy. Nineteen of 61 patients experienced local recurrence at the primary tumor and underwent analysis. The volumes of interest (VOI) on pretherapy FDG-PET were defined by use of an isocontour at ≥50% of maximum standard uptake value (SUVmax) (≥50% of SUVmax) with correction for heterogeneity. The VOI on posttherapy images were defined at ≥80% of SUVmax. The VOI of pretherapy and posttherapy 18F-FDG PET images were correlated for the extent of overlap.

Results

The size of VOI at pretherapy images was on average 25.7% (range, 8.8%-56.3%) of the pretherapy primary gross tumor volume (GTV), and their overlap fractions were 0.8 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.7-0.9), 0.63 (95% CI: 0.49-0.77), and 0.38 (95% CI: 0.19-0.57) of VOI of posttherapy FDG PET images at 10 days, 3 months, and 6 months, respectively. The residual uptake originated from the pretherapy VOI in 15 of 17 cases.

Conclusions

VOI defined by the SUVmax- ≥50% isocontour may be a biological target volume for escalated radiation dose.

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer mortality (1). Currently, patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer are treated with radiation alone for early-stage disease and with chemoradiation therapy for locally advanced disease. Therefore, radiation therapy (RT) has been the mainstay of therapy for long-term local tumor control and survival. However, despite tremendous improvement in RT technology in the past decade, the clinical outcome for patients with locally advanced lung cancer remains quite poor.

Escalated radiation dose could lead to improved local control and survival; however, it also increases the incidence and severity of radiation toxicities (2). Therefore, it is highly desirable to develop an alternative technique for dose escalation, based on a biologically guided target definition. If the dose could be escalated to a volume smaller than gross tumor volume (GTV) defined with current computed tomography (CT)-based imaging, the local tumor control might increase while the current normal tissue complication rates were maintained. An optimal balance between local control and risk of toxicity may be found through refinement of biological targets within the GTV and tolerance of organs at risk.

The 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) offers quantitative measurement of regional glucose utilization and can be used to identify biologically active volumes by outlining FDG-positive areas (3). It has been shown that the specificity of FDG-PETederived tumor volumes is superior to that of CT (4). Therefore, 18F-FDG-PETebased definition of target volumes may increase the efficacy of RT by permitting escalated dose to the regions critical for tumor control (5).

The goal of our study was to investigate whether a metabolically active subvolume of the primary tumor is likely the source of recurrence in a subset of patients (n=19) with confirmed recurrence at the primary tumor. These patients were enrolled into a prospective study (main study), whose objectives were to determine first, the earliest time point where the maximum metabolic response defined by the lowest residual FDG uptake by serial 18F-FDG PET studies is attainable after definitive RT or chemoradiation therapy and second, the optimum cutoff value of residual FDG uptake based on its predicted tumor control probability, sensitivity, and specificity. The results of the main study were published elsewhere (6). To achieve our goals, we compared subvolumes defined with different levels of FDG uptake quantified with maximum standard uptake value (SUVmax) of the pretherapy and subsequent post-therapy 18F-FDG PET of recurrent primary tumors.

Methods and Materials

This study was performed with approval of the institutional review board of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and in accord with an assurance filed with and approved by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before enrollment.

Study design

The goal of the study was to investigate the association between early 18F-FDG PET measured metabolic response and subsequent local control. Serial measurements of glucose metabolic rate were performed by use of a simplified kinetic method (SKM) and standard uptake value (SUV), a semiquantitative measure of 18F-FDG PET at the primary lung cancers, during 3 weeks before (study 1 or S1) and at 10 to 12 days (study 2 or S2), 3 months (study 3 or S3), 6 months (study 4 or S4), and 12 months (study 5 or S5) after RT or chemoradiation therapy. All patients included in the study were followed up with serial CT and 18F-FDG PET imaging studies for at least 12 months for survival and the status of local tumor control. At the time of 18F-FDG PET studies, CT of the chest was also obtained. A detailed description of the study and definitions of local control and failure were presented in our earlier publication (6).

Patients

Study eligibility included inoperable stage I-III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and limited-stage small cell lung cancer, excluding bronchoalveolar carcinoma. Other criteria included performance score (PS) 0 to 1, adequate general condition for either chemoradiation therapy or RT of curative intent, age >18 years, and absence of pregnancy. The initial evaluation included a complete history, physical examination with special attention to primary and metastatic lung cancer symptoms, and laboratory tests. Imaging studies including CT of the chest and upper abdomen, whole-body 18F-FDG PET, and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain were also used in the evaluation.

Treatments

Patients were treated with either 3-dimensional conformal RT or intensity modulated RT. Inoperable stage I NSCLC was treated with 70 to 75 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction, and inoperable stage II-III NSCLC was treated with 63 to 66.6 Gy at 1.8 Gy per fraction. Treatments were delivered in 5 fractions per week, concurrent with platinum/etoposide (50/50) chemo-therapy for patients with stage II-III NSCLC and good PS 0 to 1. Patients older than 70 years and PS 1 or 2 were treated with weekly carboplatin/paclitaxel concurrently and 2 additional cycles of high-dose consolidation carboplatin/paclitaxel.

18F-FDG PET image acquisition and reconstruction

Whole-body 18F-FDG PET imaging was performed from skull base to mid-thigh with an Siemens ECAT HR+ PET scanner (Siemens/CTI). 18F-FDG was injected intravenously with a maximum dose of 333 MBq (9 mCi). Patients fasted for at least 6 hours before scanning, and blood glucose levels were recorded before 18F-FDG injection. Patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and fasting blood glucose 200 mg/dL were excluded. Images were acquired in 6 to 7 bed positions at between 45 and 60 minutes after injection. Images were reconstructed with the ordered subset expectation maximization algorithm (2 iterations, 8 subsets) and a Gaussian filter.

Image analysis

Primary tumors and involved regional lymph nodes were analyzed with the use of 1.0 cm × 1.0 cm and 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm regions of interest (ROIs) on transaxial 18F-FDG-PET images. The maximum metabolic activity within the ROIs was quantified by both SKM and SUV methods for determination of regional glucose utilization. ROIs were defined on multiple slices of tumor on 18F-FDGPET images or on CT scans when little or no tumor-related radioactivity was discernible by visual analysis of post-therapy studies.

To analyze 18F-FGD uptake distributions, images of the SUV parameter were generated by the use of custom software. The definition of SUVmax was SUVmax Z Tcmax/(D/W), where Tcmax is the maximum concentration of 18FFDG [mCi/g], D is injected dose of 18F-FDG [mCi], and W is the body weight (7). Details of the SKM were reported elsewhere (8).

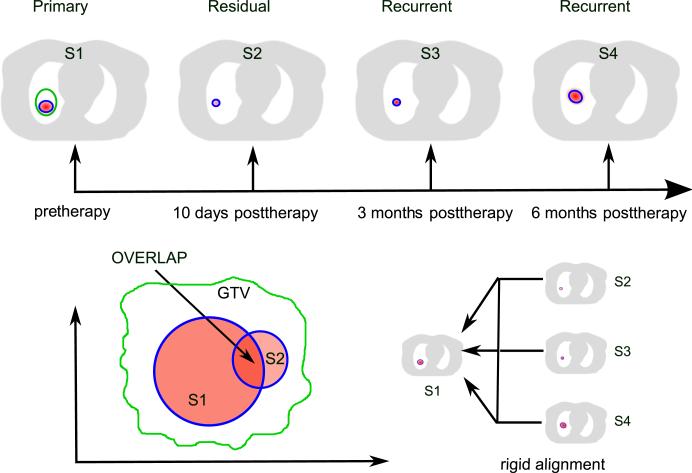

The study design is illustrated in Figure 1. One pre-therapy 18F-FDG scan and all available posttherapy 18F-FDG scans were collected for each patient. The image processing was performed as follows. First, we defined a volume of interest (VOI) on the pretherapy 18F-FDG PET image (S1) by thresholding the intensity at the level of ≥50% of SUVmax. Second, we delineated areas of high FDG uptakes on posttherapy scans. SUVmax of the active areas at 10 days (S2) and 3 months (S3) after therapy was on average 47% and 38% lower than that of pretherapy uptake (Table 1); therefore, a higher threshold at ≥80% SUVmax was used to delineate VOIs on posttherapy scans for better discrimination with adjacent tissues. Third, the pretherapy 18F-FDG PET scans (S1) were rigidly aligned with each posttherapy scan (S2, S3, S4, and S5) according to the large scale anatomy, primarily the rib cage and the spine. For that, CT and transmission images were registered, and transformed posttherapy images were transformed by use of the derived transformation matrices. Then, VOIs on pretherapy and post-therapy images were correlated with respect to their relative spatial positions. To quantify positional correlation, we calculated the overlap fraction using the following equation (9):

| (1) |

where Vpre is the volume of pretherapy VOI, Vpost is the volume of posttherapy VOI, and Vmin is the smaller of these 2.

Fig. 1.

Design of the study. Schematically shown are pretherapy scan (S1) with 50% of maximum standard uptake value of 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) uptake threshold; 10-day posttherapy (S2), 3-month posttherapy (S3), and 6-month posttherapy (S4) scans with 80% of maximum standard uptake value of FDG uptake threshold. All posttherapy scans were rigidly aligned with the pretherapy scan. Overlap of FDG uptake at S1 and each of the posttherapy uptakes within thresholds was calculated.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics

| Patient | Age | Sex | Type | TNM | GTV (cc) | Dose (Gy) | No. Fract/TTT | SUVmax of 18F-FDG PET |

Overlap fraction |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 (S5) | S2 | S3 | S4 (S5) | ||||||||

| 1 | 88 | M | SqCA | T1N0M0 | 11.79 | 70 | 35/50 | 2.45 | 1.59 | 1.53 | 1.87 (1.63) | 0.69 | 0.14 | 0.42 (1) |

| 2 | 82 | F | SqCA | T1N0M0 | 23.59 | 75 | 30/45 | 8.31 | 1.79 | 2.83 | 4.12 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0 |

| 3 | 75 | F | ADCA | T3N0M0 | 88.12 | 74 | 37/54 | 6.53 | 4.50 | 4.30 | 4.04 | 0.73 | 0.56 | 0.07 |

| 4 | 69 | F | SqCA | T2N1M0 | 48.65 | 66.6 | 37/52 | 7.69 | 1.11 | 6.65 | * | 1 | 0.87 | * |

| 5 | 76 | F | SqCA | T2N2M0 | 141.33 | 66.6 | 37/51 | 14.06 | 4.32 | 1.00 | 3.53 | 1 | 0.63 | 1 |

| 6 | 84 | F | NSCLC | T2N2M0 | 41.95 | 72 | 40/58 | 9.20 | 1.66 | 2.30 | * | 0.71 | 0.8 | * |

| 7 | 61 | F | SqCA | T3N0M0 | 35.23 | 63 | 35/54 | 3.10 | 1.61 | 3.52 | 1.78 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 1 |

| 8 | 82 | M | ADCA | T2N2M0 | 88.50 | 72 | 40/52 | 9.38 | 1.32 | 2.58 | 6.03 | 0.76 | 1 | 0.12 |

| 9 | 56 | F | NSCLC | T2N3M0 | 141.13 | 63 | 35/62 | 19.08 | 7.53 | 4.25 | 3.02 (8.22) | 0.94 | 0.04 | 0.12 (0.03) |

| 10 | 74 | M | SqCA | T3N0M0 | 106.18 | 72 | 40/71 | 3.28 | 2.48 | 2.00 | 5.12 | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.42 |

| 11 | 75 | F | NSCLC | T3N0M0 | 42 | 72 | 40/60 | 10.40 | 2.59 | 2.32 | * | 11 | * | |

| 12 | 78 | F | SqCA | T3N1M0 | 37.19 | 70 | 35/52 | 7.93 | 2.59 | 5.19 | * | 11 | * | |

| 13 | 69 | F | SqCA | T3N2M0 | 133.35 | 63 | 35/79 | 15.11 | 2.95 | 6.20 | 6.65 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.07 |

| 14 | 66 | F | NSCLC | T3N2M0 | 237.61 | 63 | 35/60 | 9.59 | 3.17 | 2.05 | 3.03 | 0.97 | 0.5 | 0.51 |

| 15 | 75 | M | SqCA | T3N3M0 | 173.84 | 72 | 40/55 | 5.17 | 4.08 | 4.43 | 3.18 | 0.44 | 0.4 | 0.04 |

| 16 | 75 | M | † | T1N1M0 | 24.55 | 72 | 40/60 | 8.70 | 1.79 | 3.95 | 3.34 | 0.93 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| 17 | 65 | M | SqCA | T4N2M0 | 424.97 | 66.6 | 37/54 | 15.02 | 2.65 | 2.18 | 6.87 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.57 |

| Mean | 73.5 | 96.07 | 69 | 37/56.6 | 9.12 | 2.81 | 3.37 | 4.05 | 0.8 | 0.63 | 0.38 | |||

| Std | 8.4 | 103.4 | 4.2 | 2.7/7.5 | 4.59 | 1.6 | 1.63 | 1.67 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.35 | |||

| Median | 75 | 88.12 | 70 | 37/54 | 8.7 | 2.59 | 2.83 | 3.53 | 0.76 | 0.63 | 0.42 | |||

| Min | 56 | 11.79 | 63 | 30/45 | 2.45 | 1.11 | 1 | 1.78 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 0 | |||

| Max | 88 | 424.97 | 75 | 40/79 | 19.08 | 7.53 | 6.65 | 6.87 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

Abbreviations: 18F-FDG PET = 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography; ADCA = adenocarcinoma; Fract = fraction; GTV = gross tumor volume; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; S1 = pretherapy study; S2 = 10- to 12-day posttherapy; S3 = 3-month post-therapy; S4 = 6-month posttherapy; S5 = 12-month posttherapy; SqCA = squamous cell carcinoma; SUVmax = maximum standard uptake value; TTT = total treatment time (days).

18F-FDG PET was not obtained because local recurrence was diagnosed before 6 months and patients were removed from protocol specified imaging studies.

Clinical diagnosis of lung cancer based on a growing mass lesion in the right lung by serial chest CT and increased uptake by 18F-FDG PET in a patient with prior left pneumonectomy.

Analysis of spatial patterns of the distributions of FDG uptake of the primary tumors revealed both homogeneous and heterogeneous distributions. Homogeneous distribution is characterized by radially homogeneous intensity within an elliptical shape. Any spatial deviation from that is considered to be a heterogeneous uptake distribution (10). Most of the VOIs on pretherapy scan had homogeneous activity distribution. Heterogeneous VOIs needed additional processing to smoothen out heterogeneities. For that, we applied a convex hull algorithm establishing a convex boundary that includes all uptake domains (11).

Results

Patient demographics and tumor characteristics

We accrued 106 patients, of whom 61 were able to complete the serial 18F-FDG PET studies. The clinical and tumor characteristics of these 106 patients were reported earlier (6).

Although 19 of 61 patients experienced local failure at the primary tumor in 3 to 9 months after therapy, 2 patients, 1 with a very bulky disease and 1 with arm position mismatch, were excluded from the data set for low-quality registration, yielding a final set of 17 patients whose clinical and tumor characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Regional nodal metastasis was present in 11 of 17 patients, and 2 of these 11 showed nodal recurrences as well. However, these nodal recurrences were not located close to residual/recurrent primary tumors and did not affect the analysis of FDG uptake at the primary tumors.

Posttherapy 10-day (S2) and 3-month (S3) 18F-FDG PET scans were available for all 17 patients; 6-month (S4) posttherapy scans were available for 13 of 17 patients, and 12-month (S5) posttherapy scans were available for 2 patients only. Patients were removed from the study as recurrence of the primary tumor was confirmed, and no additional 18F-FDG PET studies were acquired unless such studies were clinically indicated. The mean SUVmax measured before treatment was 9.12 (Table 1). At the 10-day follow-up visit, the mean SUVmax decreased to 2.81, with 7 tumors having SUVmax below 2. However, 6 of these 7 tumors showed an increase in SUVmax at the 3-month follow-up visit, the mean being 3.37. By the 6-month follow-up visit, the mean SUVmax increased to 4.05. One patient consistently showed SUVmax below 2 at all post-therapy measurements, and chest CT showed a steady increase in tumor size. The recurrence was confirmed by a fine needle aspiration biopsy.

Volumes of interest

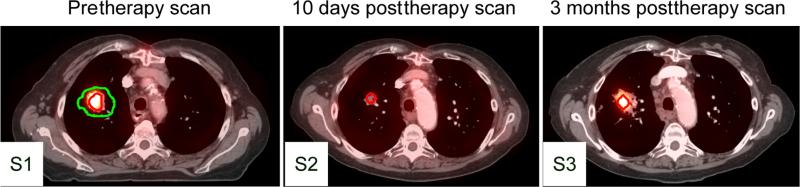

The VOI on pretherapy scan was compared with manually delineated GTV of primary tumor as defined on the planning CT. On average, the size of the VOI was 25.7% (range, 8.8% to 56.3%) of the GTV. Figure 2 demonstrates a representative set of 3 studies. In S1 scan the VOI is outlined by red contour and the pretherapy GTV by green contour. The red contour in S2 and S3 scans represents the high FDG uptake volumes defined by SUVmax-80%.

Fig. 2.

Representative images of a patient with pretherapy (S1) and 10-day (S2) and 3-month (S3) posttherapy 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography computed tomography (18F-FDG PET-CT). Green line indicates gross tumor volume outlined on pretherapy CT. Red lines indicate 50% of maximum standard uptake value threshold of FDG uptake on pretherapy PET (S1) and 80% of maximum standard uptake value threshold of FDG uptake on posttherapy PETl (S2,S3). A color version of this figure is available at www.redjournal.org.

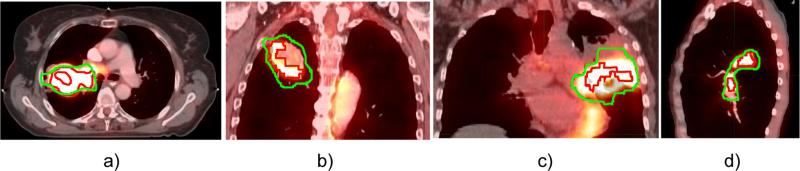

Analyzing the morphology of the 17 pretherapy VOI, we found that 10 were closed spheroid volumes with homogeneous uptake distribution as shown in Figure 2. The size of the corresponding GTVs was on average 54.8 cm3 (range, 11.8-141.1 cm3). This group included 2 stage I tumors, 3 stage II tumors, and 5 stage III tumors. Seven tumors showed a heterogeneous uptake distribution as shown in Figure 3. Among them, 4 tumors (1 of stage II and 3 of stage III) showed heterogeneous uptakes with embedded low-uptake central regions that might correspond to a hypoxic or necrotic core (Fig. 3a-c). The mean size of these GTVs was 201.5 cm3 (range, 106.2-425.0 cm3), in accordance with previous findings that large GTVs show higher heterogeneity (12). Three stage III tumors (GTVs 35.2 cm3, 173.8 cm3, and 273.6 cm3) showed multiple isolated uptake domains (Fig. 3d). These heterogeneous volumes were processed to create a convex VOI. When a low-uptake region was completely enveloped by the threshold volume, the VOI was defined by the outer isocontour (Fig. 3a). When the region was partially enveloped, we applied the convex hull algorithm to include it into the VOI (Fig. 3b, c).

Fig. 3.

Examples of heterogeneous 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) uptake distribution in 4 different tumors. Green contour indicates gross tumor volume outlined on pretherapy computed tomography. Red contour indicates 50% of maximum standard uptake value threshold of FDG uptake on pretherapy positron emission tomography. A color version of this figure is available at www.redjournal.org

Overlap fractions

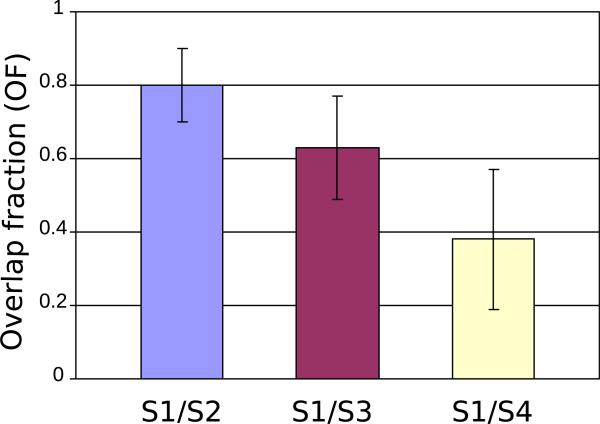

We correlated volumes of FDG uptake measured 10 to 12 days (S2), 3 months (S3), and 6 months posttherapy (S4) with that of pretherapy by calculating the overlap fraction, given by Eq. (1). The average overlap fraction with the earliest posttherapy uptake (S2) was 80% (95% CI: 70%-90%) and it declined to 63% (95% CI: 49%-77%) for S3 and to 38% (95% CI: 19%-57%) for S4 18F-FDG PET scans as shown in Figure 4. Visual analysis of the scans suggested that the decline in the overlap fraction with time resulted from tumor progression into adjacent pulmonary tissue in uneven manner.

Fig. 4.

Overlap fractions of the pretherapy (S1) with 3 posttherapy (S2, S3, S4) 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose uptakes calculated for 17 patients. Data are expressed as means ±95% confidence intervals.

For most patients, the common pattern of overlap included a high overlap fraction at the earliest posttherapy scan, followed by decreasing overlap fraction at the 3- and 6-month posttherapy scans as presented in Figure 4.

We also looked at the voxel location of SUVmax of 18F-FDG PET 10-day posttherapy relative to the overlap volume. As a predictor of recurrence location, the residual uptake originates from the pretherapy VOI in most cases (15 of 17).

Discussion

Standard RT of NSCLC with 60 Gy is associated with a 45% to 50% rate of local recurrence (13). In the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0617 trial, the standard radiation dose schedule of 60 Gy in 30 fractions for 6 weeks was compared with an escalated dose schedule of 74 Gy in 37 fractions for 7.4 weeks in combination with concurrent chemotherapy and with or without cetuximab for patients with inoperable stage IIIA and IIIB NSCLC (14). The median survival time and 18-month survival rates were 28.7 months and 66.9% with 60 Gy versus 19.5 months and 53.9% with 74 Gy, respectively. In these early findings, the outcomes in the higher-dose arm were inferior to those in the standard-dose arm.

To explore the utility of pretherapy 18F-FDG PET for guiding biologically optimized RT, we propose that more probable locations of residual cancer and recurrence can be the target for additional radiation. At the same time, high levels of pretherapy 18F-FDG uptake alone are not always indicative of posttherapy recurrence. Thus, in RT for lung cancer, dose painting still remains an attractive concept that needs further validation.

Nonetheless, we have shown that for patients with local recurrence, high-uptake regions (≥50% value of SUVmax) of pretherapy 18F-FDG-PET scans spatially correlate with ≥80% value of SUVmax of residual cancer. This finding suggests that in patients with a high risk for local recurrence (eg, by virtue of large tumor size) (15), the regions determined by SUVmax-50% on pretherapy FDG-PET may represent targets for dose escalation.

Table 2 shows a comparison of the results of 4 recent studies on the correlation between pretherapy FDG up-take and FDG uptake of recurrent lung cancer. Abramyuk et al (16) correlated pretherapy FDG uptakes with FDG uptakes obtained 8 months after therapy in 10 patients. Only qualitative observations were made. The overlap was good for small tumors but poor for large tumors.

Table 2.

Comparison with previous work

| Study | No. of tumors | Time of PET follow-up (range) | Location of residual FDG avidity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abramyuk et al, 2009 (16) | 10 | 8 months (6-9 months) | Small tumors (<10 cm3) - center of baseline FDG uptake Large tumors (>10 cm3)- within 35% SUVmax of baseline FDG uptake |

| Aerts et al, 2009 (9) | 22 | 3 months (49-184 days) | Overlap fraction of 50% of SUVmax of baseline FDG uptake with 80% of SUVmax of residual FDG uptake - 0.77 (95% CI: 0.66-0.88) |

| Aerts et al, 2012 (17) | 7 | 3 months | Overlap fraction of 50% of SUVmax of baseline FDG uptake with 70%-90% of SUVmax of residual FDG uptake: 67.9 ± 6.8% (range, 61.5-82.6%) |

| Present study | 17 | 10 days (10-17 days) 3 months (61-139 days) 6 months (181-212 days) |

Overlap fraction of 50% of SUVmax of baseline FDG uptake with 80% of SUVmax of residual FDG uptake 0.80 (95% CI: 0.7-0.9): 10 days after RT 0.63 (95% CI: 0.49-0.77): 3 months 0.38 (95% CI: 0.19-0.57): 6 months |

Abbreviations: FDG = 2-deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose; PET = positron emission tomography; RT = radiation therapy; SUVmax = maximum standard uptake value.

Aerts et al (9, 17) used quantitative measure for correlation between ≥50% value of SUVmax of pretherapy uptake and ≥80% value of SUVmax of posttherapy residual uptake. Residual uptake was defined as SUV higher than blood 18F-FDG activity at the aortic arch. The overlap fractions were 77% at 3 months for the retrospective study (n=22) and 68% for the prospective study (n=7).

In the present study, we correlated metabolic volumes defined with ≥80% value of SUVmax obtained at S2, S3, and S4 18F-FDG-PET with metabolic volumes defined with ≥50% value of SUVmax of pretherapy 18F-FDG PET. As expected, the highest overlap, 80%, was observed for the early posttherapy study, subsequently decreasing to 63% and 38% in the 3-month and 6-month studies. Interestingly, our finding of overlap fraction of 63% in the 3-month posttherapy study is comparable to the overlap fraction of 68% in the prospective study by Aerts et al (17), also at 3 months. Given that recurrent tumor grows locally, its invasion into adjacent lung tissue and bronchus depends on many factors, including blood supply, and is expected to be nonuniform. This is likely the reason why overlap fraction becomes smaller as recurrent tumor grows larger.

The use of a specific threshold of FDG uptake for defining metabolic target volume has been extensively discussed in the literature. The most commonly used thresholding methods are based on the fixed percentage of the maximum SUV (18, 19) or are adapted to background threshold (20). It was shown that both fixed SUVmax-50% and adaptive thresholds fit well the histopathologic maximum diameter. The adaptive threshold approach takes into account tumor-to-background ratio, but it requires definition of the background for each image and needs optimization for each scanner model. Therefore, fixed SUV threshold is easier to implement in routine clinical practice. Moreover, the value of the fixed threshold can be adjusted during planning to satisfy dose constraints for normal tissues.

We also addressed the problem of quantification of tumor targets in the presence of heterogeneities. This problem has been widely discussed in the literature and various methods have been proposed, including fuzzy C-means algorithms (21) and maximum-intensity projection methods (22). We propose a simple semiautomatic intensity threshold-based method that requires additional processing for heterogeneous uptakes, using a convex hull algorithm (11) to define the outer boundary that includes all target domains.

Application of this new information is somewhat limited at this time because the pretherapy FDG uptake alone is not a good predictor of local recurrence. However, patients with high risk factors for local failure, such as large tumor size and tumor hypoxia, may potentially benefit from a dose-painting approach that uses pretherapy FDG PET.

Summary.

This study reports the spatial correlation between 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) uptakes measured before and after radiation therapy of lung cancer for a cohort of patients who experienced local recurrence. A high correlation between the pretreatment FDG volume and the posttreatment volume was found. This supports the concept of using FDG uptake to define target volumes for dose escalation for patients with a high risk for local recurrence.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grant RO1 EB002907 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarz M, Alber M, Joos Lebesque JV, et al. Dose heteroheneity in the target volume and intensity-modulated radiotherapy to escalate the dose in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:561–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nestle U, Kremp S, Grosu AL. Practical integration of [18F]-FDG-PET and PET-CT in the planning of radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): The technical basis, ICRU-target volumes, problems, perspectives. Radiother Oncol. 2006;81:209–225. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, Boersma L, et al. PET-CT-based auto-contouring in non-small-cell lung cancer correlates with pathology and reduces interobserver variability in the delineation of the primary tumor and involved nodal volumes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ling CC, Humm J, Larson S, et al. Towards multidimensional radiotherapy (MD-CRT): Biological imaging and biological conformity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:551–560. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00467-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi NC, Chun TT, Niemierko A, et al. Potential of F-18-FDG PET toward personalized radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:832–841. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2348-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryu JS, Choi NC, Fischman AJ, et al. FDGPET in staging and restaging non-small cell lung cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: Correlation with histopathology. Lung Cancer. 2002;35:179–187. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter GJ, Hamberg LM, Alpert N, et al. Simplified measurement of deoxyglucose utilization rate. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:950–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aerts HJWL, van Baardwijk AAW, Petit SF, et al. Identification of residual metabolic-active areas within individual NSCLC tumors using a pre-radiotherapy 18Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET-CT scan. Radiother Oncol. 2009;91:386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Sullivan F, Roy S, Eary J. A statistical measure of tissue heterogeneity with application to 3D PET sarcoma data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:433–448. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barber CB, Dobkin DP, Huhdanpaa HT. The quickhull algorithm for convex hulls. ACM Trans Math Softw. 1996;22:469–483. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatt M, Cheze le Rest C, Descourt P, et al. Accurate automatic delineation of heterogeneous functional volumes in positron emission tomography for oncology applications. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Machtay M, Bae K, Movsas B, et al. Higher biologically effective dose of radiotherapy is associated with improved outcomes for locally advanced nonesmall cell lung carcinoma treated with chemoradiation: An analysis of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley J, Paulus R, Komaki R, et al. A randomized phase III comparison of standard-dose (60 Gy) versus high-dose (74 Gy) conformal chemoradiotherapy with or without cetuximab for stage III non-small cell lung cancer: Results on radiation dose in RTOG 0617. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2013;31:458s. (abstr 7501) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley JD, Leumwananonthachai N, Purdy JA, et al. Gross tumor volume, critical prognostic factor in patients treated with three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy for non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abramyuk A, Tokalov S, Zöphel K, et al. Is pre-therapeutical FDGPET/CT capable to detect high risk tumor subvolumes responsible for local failure in non-small cell lung cancer? Radiother Oncol. 2009;91:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aerts HJWL, Bussink J, Oyen WJG, et al. Identification of residual metabolic-active areas within NSCLC tumours using a preradiotherapy FDG-PET-CT scan: A prospective study. Lung Cancer. 2012;75:73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu K, Ung YC, Hornby J, et al. PET CT thresholds for radiotherapy target definition in non-small-cell lung cancer: How close are we to the pathologic findings? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:699–706. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatt M, Cheze-le Rest C, van Baardwijk A, et al. Impact of tumor size and tracer uptake heterogeneity in 18F-FDG PET and CT nonesmall cell lung cancer tumor delineation. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1690–1697. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.092767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nestle U, Kremp S, Schaefer-Schuler A, et al. Comparison of different methods for delineation of 18F-FDG PET-positive tissue for target volume definition in radiotherapy of patients with non-small lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1342–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belhassen S, Zaidi H. A novel fuzzy C-means algorithm for unsupervised heterogeneous tumor quantification in PET. Med Phys. 2010;37:1309–1324. doi: 10.1118/1.3301610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewalle-Vignion AS, Betrouni N, Lopes R, et al. A new method for volume segmentation of PET images, based on possibility theory. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2011;30:409–423. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2083681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]