Abstract

Background

Antisocial personality disorder (AsPD) is associated with a wide range of disturbance including persistent rule-breaking, criminality, substance use, unemployment, homelessness and relationship difficulties.

Objectives

To evaluate the potential beneficial and adverse effects of psychological interventions for people with AsPD.

Search methods

Our search included CENTRAL Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ASSIA, BIOSIS and COPAC.

Selection criteria

Prospective, controlled trials in which participants with AsPD were randomly allocated to a psychological intervention and a control condition (either treatment as usual, waiting list or no treatment).

Data collection and analysis

Three authors independently selected studies. Two authors independently extracted data. We calculated mean differences, with odds ratios for dichotomous data.

Main results

Eleven studies involving 471 participants with AsPD met the inclusion criteria, although data were available from only five studies involving 276 participants with AsPD. Only two studies focused solely on an AsPD sample. Eleven different psychological interventions were examined. Only two studies reported on reconviction, and only one on aggression. Compared to the control condition, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) plus standard maintenance was superior for outpatients with cocaine dependence in one study, but CBT plus treatment as usual was not superior for male outpatients with recent verbal/physical violence in another. Contingency management plus standard maintenance was superior for drug misuse for outpatients with cocaine dependence in one study but not in another, possibly because of differences in the behavioural intervention. However, contingency management was superior in social functioning and counselling session attendance in the latter. A multi-component intervention utilising motivational interviewing principles, the ‘Driving Whilst Intoxicated program’, plus incarceration was superior to incarceration alone for imprisoned drink-driving offenders.

Authors’ conclusions

Results suggest that there is insufficient trial evidence to justify using any psychological intervention for adults with AsPD. Disappointingly few of the included studies addressed the primary outcomes defined in this review (aggression, reconviction, global functioning, social functioning, adverse effects). Three interventions (contingency management with standard maintenance; CBT with standard maintenance; ‘Driving Whilst Intoxicated program’ with incarceration) appeared effective, compared to the control condition, in terms of improvement in at least one outcome in at least one study. Each of these interventions had been originally developed for people with substance misuse problems. Significant improvements were mainly confined to outcomes related to substance misuse. No study reported significant change in any specific antisocial behaviour. Further research is urgently needed for this prevalent and costly condition.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Aggression [psychology], Antisocial Personality Disorder [*therapy], Cocaine-Related Disorders [therapy], Cognitive Therapy [methods], Psychotherapy [*methods], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Reward

MeSH check words: Adult, Female, Humans, Male

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Antisocial personality disorder (AsPD) is one of the ten personality disorder categories in the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; APA 2000). DSM-IV defines personality disorder as: ‘an enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviour that deviates markedly from the expectations of the person’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is stable over time, and leads to distress or impairment’. General criteria for personality disorder according to DSM-IV are given in Table 1 below.

Table 1. DSM-IV general criteria for personality disorder.

|

AsPD is identified by traits that include irresponsible and exploitive behaviour, recklessness, impulsivity, high negative emotionality and deceitfulness. In order to be diagnosed with AsPD, according to the DSM-IV, a personmust fulfil criteria A, B, C and D shown in Table 2 below as well as fulfilling general criteria for a personality disorder as outlined above.

Table 2. DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for AsPD (APA 2000).

|

The focus of this review is antisocial personality disorder, although this condition is also often classified using the International Classification of Diseases - tenth edition (ICD-10; WHO 1992) as dissocial personality disorder (F60.2). AsPD and dissocial personality disorder are often used interchangeably by clinicians and they describe a very similar presentation. While there is considerable overlap between these two diagnostic systems, they differ in two respects. First, DSM-IV requires that those meeting the diagnostic criteria also show evidence of conduct disorder with onset before the age of 15 years and there is no such requirement when making the diagnosis of dissocial personality disorder using ICD-10 criteria. However, a study by Perdikouri et al (Perdikouri 2007) did not find any clinically important differences when they compared subjects meeting the full criteria for AsPD with those who otherwise fulfilled criteria for AsPD but who did not demonstrate evidence of childhood conduct disorder. Second, dissocial personality disorder focuses more on the interpersonal deficits (for example, incapacity to experience guilt, a very low tolerance of frustration, proneness to blame others) and less on antisocial behaviour. Table 3 below shows the diagnostic criteria for diagnosing dissocial personality disorder. Second, it has been argued that the criteria in ICD-10 are more reflective of the core personality traits of the antisocial with less emphasis on criminal behaviour.

Table 3. ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for dissocial personality disorder (F60.2) (WHO 1992).

|

Whilst estimates of the prevalence of AsPD in the general population vary across studies and countries, most studies report a prevalence of between 2% and 3% in the general population (Coid 2006; Moran 1999). Prevalence rates are consistently higher in men compared with women (Dolan 2009). For instance, the lifetime prevalence in two North American studies was 4.5% among men and 0.8% among women (Robins 1991) and 6.8% among men and 0.8% in women (Swanson 1994). However, two European studies found lower prevalence rates (i.e. of 1.3% in men and 0% in women (Torgensen 2001) and 1% in men and 0.2% in women (Coid 2006)). As would be expected AsPD is especially common in prison settings. In the UK prison population, the prevalence of people with AsPD has been identified as 63% in male remand prisoners, 49% in male sentenced prisoners and 31% in female prisoners (Singleton 1998).

The condition is associated with a wide range of disturbance and is associated with greatly increased rates of criminality, substance use, unemployment, homelessness and relationship difficulties. Antisocial personality disorder is generally associated with a negative long-term outcome. Many adults with AsPD are imprisoned at some point in their life. Although follow-up studies have demonstrated some improvement over time, particularly in rates of re-offending (Grilo 1998; Weissman 1993), men with AsPD who reduce their offending behaviour over time may nonetheless continue to have major problems in their interpersonal relationships (Paris 2003). Black found that men with AsPD aged less than 40 years had a strikingly high rate of premature death and obtained a value of 33 for the Standardised Mortality Rate (the age-adjusted ratio of observed deaths to expected deaths - meaning that they were 33 times more likely to die than similar males of the same age without this condition) (Black 1996). This increased mortality was due not only to an increased rate of suicide, but was also associated with reckless behaviours such as drug misuse and aggression. Follow-up studies in forensic-psychiatric settings suggest a similarly concerning picture. For example, Davies 2007 reported that 20 years after discharge from a medium secure unit almost half of the patients were reconvicted, with reconviction rates higher in those with personality order compared to mentally ill patients.

Significant comorbidity exists between AsPD and many Axis I disorders; mood and anxiety disorders are common, although the most frequent co-occurrence is with substance misuse. Men with AsPD have been found to be three to five times more likely to abuse alcohol and illicit drugs than those without the disorder (Robins 1991). The presence of personality disorder co-occurring with an Axis I condition may have a negative impact on the outcome of the latter (Newton-Howes 2006; Skodol 2005).

Description of the intervention

Psychological interventions have traditionally been the mainstay of treatment for AsPD, but the evidence upon which this is based is weak (Duggan 2007; NIHCE 2009). Psychological therapies encompass a wide range of interventions (Bateman 2004) but may be broadly classified into four main categories:

psychoanalytic psychotherapy;

cognitive behavioral;

therapeutic community; and

nidotherapy.

Traditionally, psychoanalytically-based psychological therapies held sway but latterly these have been replaced by more cognitive behavioral therapy-based approaches (Cordess 1996).

It is important to consider all relevant studies without restriction on the type of psychological therapy and to consider psychological interventions where drugs are also given as an adjunctive intervention.

How the intervention might work

Psychoanalytic therapies (which include dynamic psychotherapy, transference-focused psychotherapy, mentalisation-based therapy and group psychotherapy) aim to help the patient understand and reflect on his inner mental processes and make links between his past and his current difficulties. To our knowledge, no randomised trials have been published assessing the efficacy of dynamic psychotherapies specifically for AsPD but there are a small number of trials which examined the effectiveness of psychoanalytic therapies for personality disorder in general. Limited evidence for the efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy comes from Bateman 2001, Chiesa 2003, Piper 1993 and Winston 1994.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) based treatments place emphasis on encouraging the patient to challenge their core beliefs and to gain insight into how their thoughts and feeling affect their behaviour. A review of the evidence for this form of intervention concluded that “the overall evidence in favour of cognitive behavioural therapy in the treatment of personality disorder is therefore relatively slim, with much of the evidence coming from one research group, but it has involved more patients than any other form of treatment” (Bateman 2004).

Dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) is a complex psychological intervention which was developed using some of the principles of CBT (Linehan 1993) and may help change behaviour by improving skills and the ability to contain difficult feelings. It is currently popular, but the evidence for its efficacy is less clear with some reviewers considering that its only proven benefit appears to be in the reduction of self-harm episodes (Bateman 2004). Cognitive analytic therapy (CAT) is a brief psychological therapy utilising ideas from psychodynamic psychotherapy, cognitive therapy and cognitive psychology (Denman 2001).

Therapeutic community treatments involve patients (also known as residents) not only having therapy together but also working and living together in a shared, therapeutic environment. This provides them with an opportunity to “explore intrapsychic and interpersonal problems and find more constructive ways of dealing with distress” (Campling 2001). Therapeutic community treatment is the only single treatment modality for severe personality disorder (which is likely to encompass AsPD and some other forms of personality disorder) that has been subject to a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. This demonstrated the effectiveness of therapeutic community treatment (Lees 1999) but several of the included studies did not specifically identify the participants as suffering from AsPD.

Nidotherapy is a formalised, planned method for achieving environmental change to minimise the effect of the patient’s disorder upon themselves and others. The effectiveness of this treatment has not yet been established. Unlike most other therapies it aims to fit the immediate environment to the patient rather than change the patient to cope in the existing environment (Tyrer 2007). Whilst the eventual outcome of nidotherapy is environmental manipulation, it may be regarded as a psychological intervention in that it relies upon first developing a psychological understanding of the person’s strengths and difficulties. From this psychological formulation there follows goal setting from which flows the necessary changes in the person’s physical and social environment (Tyrer 2005a).

Why it is important to do this review

Antisocial personality disorder is an important condition that has a considerable impact on individuals, families and society. Even by the most conservative estimate, AsPD appears to have the same prevalence in men as schizophrenia, the condition that receives the greatest attention from mental health professionals. Furthermore, AsPD is associated with significant costs, arising from emotional and physical damage to victims, damage to property, use of police time and involvement of the criminal justice system and prison services. Related costs include increased use of healthcare facilities, lost employment opportunities, family disruption, gambling and problems related to alcohol and substance misuse (Home Office 1999; Myers 1998). In one study the lifetime public services costs for a group of adults with a history of conduct disorder (of which 50% will go onto develop adult AsPD) were found to be 10 times those for a similar group without the disorder (Scott 2001).

AsPD is closely associated with criminal offending and any intervention that seeks to improve the outcome of AsPD is also likely to impact upon this offending. Aos 2001 reported that “for some crimes (especially those involving violence), the cost benefits in favour of intervention are often considerable as the costs of these types of crimes are often very high”.

Despite this, there is currently a dearth of evidence on how best to treat people diagnosed with AsPD, and to date the few reviews that have been carried out have been inconclusive and hampered by poor methodology. These issues were highlighted in Dolan and Coid’s (Dolan 1993) extensive review of the treatment of psychopathic and antisocial personality disorders. Unfortunately the challenge to produce high quality research in this area does not appear to have been fully taken up by the research community. This led a recent Review of Treatments for Severe Personality Disorder by the United Kingdom’s Home Office (Warren 2003) to wryly comment that “Despite the 1,600 copies of Dolan and Coid’s review having been purchased by clinicians, academics and institutions the methodological issues which were clearly set out in that review appear not to have been taken on board by the scientific community or those who fund research”. Similarly the recently published NICE clinical guidelines on the treatment of AsPD (NIHCE 2009, p.5) commented that there were “significant limitations to the evidence base, notably a relatively small number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions with few outcomes in common”.

It is hoped that there will now have been additional good quality studies to address this important topic. Furthermore, a Cochrane Review of psychological treatments for AsPD will highlight areas where more work is needed and hopefully stimulate research interest.

OBJECTIVES

This review aims to evaluate the potential beneficial and adverse effects of psychological interventions for people with antisocial personality disorder.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Controlled trials in which participants have been randomly allocated to an experimental group and a control group, where the control condition is either treatment as usual, waiting list or no treatment. We included all relevant randomised controlled trials, with or without blinding of the assessors, and published in any language.

Types of participants

Men or women 18 years or over with a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder defined by any operational criteria such as DSM-IV, or dissocial personality disorder as defined by operational criteria such as ICD-10. We included studies of people diagnosed with comorbid personality disorders or other mental health problems other than the major functional mental illnesses (i.e. schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder). The decision to exclude persons with co-morbid major functional illness is based on the rationale that the presence of such disorders (and the possible confounding effects of any associated management or treatment) might obscure whatever other psychopathology (including personality disorder) might be present and make it more difficult to evaluate the potential effect of any intervention. We placed no restrictions on setting and included studies with participants living in the community as well as those incarcerated in prison or detained in hospital.

Types of interventions

We included studies of psychological interventions, both group and individual-based. This included, but was not limited to, interventions such as:

behaviour therapy;

cognitive analytic therapy;

cognitive behavioural therapy;

dialectical behaviour therapy;

group psychotherapy;

mentalisation-based therapy;

nidotherapy;

psychodynamic psychotherapy;

schema focused therapy;

social problem-solving therapy; and

therapeutic community treatment.

Psychological interventions were subclassified into single modality and complex psychological interventions. Single modality psychological interventions are those that only involve one specific type of intervention. Such interventions include cognitive analytic therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy. Complex psychological interventions are those that involve more than one modality of treatment (for example, group therapy plus individual therapy) and include dialectical behaviour therapy and psychodynamic psychotherapy with partial hospitalisation (Campbell 2000).

We included studies of psychological interventions where medication was given as an adjunctive intervention, but reported separately any studies where the comparison is between a psychological and a pharmacological intervention.

Studies comparing two or more different therapeutic modality groups but without a control group are not included in the review.

Types of outcome measures

Primary and secondary outcomes are listed below in terms of single constructs. We anticipated that a range of outcome measures would have been used in the studies included in the review (for example, aggression may be measured by a self-report instrument or by an external observer).

Primary outcomes

Aggression

reduction in aggressive behaviour or aggressive feelings; continuous outcome, measured through improvement in scores on the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ; Buss 1992), the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS; Malone 1994) or similar validated instrument; or as number of observed incidents.

Reconviction

measured as overall reconviction rate for the sample, or as mean time to reconviction.

Global state/functioning

continuous outcome, measured through improvement on the Global Assessment of Functioning numeric scale (GAF; APA 2000).

Social functioning

continuous outcome, measured through improvement in scores on the Social Adjustment Scale (SAS-SR; Weissman 1976), the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ; Tyrer 2005b) or similar validated instrument.

Adverse events

measured as incidence of overall adverse events and of the three most common adverse events; dichotomous outcome, measured as numbers reported.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life

self-reported improvement in overall quality of life; continuous outcome, measured through improvement in scores on the European Quality Of Life instrument (EuroQol; EuroQoL group 1990) or similar validated instrument.

Engagement with services

health-seeking engagement with services measured though improvement in scores on the Service Engagement Scale (SES; Tait 2002), or similar validated instrument.

Satisfaction with treatment

continuous outcome; measured through improvement in scores on the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8; Attkisson 1982) or similar validated instrument.

Leaving the study early

measured as proportion of participants discontinuing treatment.

Substance misuse

measured as improvement on the Substance Use Rating Scale, patient version (SURSp; Duke 1994) or similar validated instrument. Where possible, drug misuse outcomes and alcohol misuse outcomes were differentiated.

Employment status

measured as number of days in employment over the assessment period.

Housing/accommodation status

measured as number of days living in independent housing/accommodation over the assessment period.

Economic outcomes

any economic outcome, such as cost-effectiveness measured using cost-benefit ratios or incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs).

Impulsivity

self-reported improvement in impulsivity; continuous outcome, measured through reduction in scores on the Barratt Impulsivity Scale (BIS; Patton 1995) or similar validated instrument.

Anger

self-reported improvement in anger expression and control; continuous outcome, measured through reduction in scores on the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-II; Spielberger 1999) or similar validated instrument.

Whilst acknowledging that the nature of the disorder can lead to difficulty in long-term follow up of individuals with AsPD, we aimed to report relevant outcomes without restriction on period of follow up. We aimed to divide outcomes into immediate (within six months), short-term (> 6 months to 24 months), medium term (> 24 months to five years) and long-term (beyond five years) if there were sufficient studies to warrant this.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The following electronic databases were searched to September 2009:

MEDLINE (from 1950);

EMBASE (from 1980);

CINAHL (from 1982);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2009, issue 3);

PsycINFO (from 1872);

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s register of trials related to forensic mental health;

ASSIA;

BIOSIS;

COPAC;

Dissertation Abstracts;

ISI-Proceedings;

ISI-SCI (Science Citation Index);

ISI-SSCI (Social Sciences Citation Index);

OpenSIGLE;

Sociological Abstracts;

ZETOC;

National Criminal Justice Reference Service Abstracts;

UK Clinical Trials Gateway*;

ClinicalTrials.gov*;

Action Medical Research*;

King’s College London (UK)*;

ISRCTN Register*;

The Wellcome Trust Register*;

NHS Trusts Clinical Trials Register*;

NHS R & D Health Technology Assessment Programme Register (HTA)*; and

NHS R & D Regional Programmes Register*.

*Searched using the meta Register of Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled-trials.com/mrct/).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of included and excluded studies for additional relevant trials. We examined bibliographies of systematic review articles published in the last five years to identify relevant studies. We contacted authors of relevant studies to enquire about other sources of information and the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Because this review is part of a larger series of reviews of personality disorders, the selection of studies was carried out in two stages. In the first stage, titles and abstracts were read independently by two review authors (JS and NH) against the inclusion criteria to identify all studies carried out with participants with personality disorder, regardless of any specific personality disorder(s) diagnosed. In the second stage, full copies of studies identified in stage one were assessed against the inclusion criteria by two review authors independently (SG and BV). This second stage assessment identified not only trials with participants diagnosed with antisocial or dissocial PD, but also trials with participants having a mix of PDs for which data on a subgroup with antisocial or dissocial PD might be available.

Studies with two treatment conditions in which the relevant participants formed a small subgroup were only included if the trial investigators randomised at least five people with antisocial or dissocial personality disorder. The rationale is that variance and standard deviation cannot be calculated in samples of two or less, and a two-condition study that randomises less than five relevant participants will have at least one arm for which variance or standard deviation cannot be calculated.

Uncertainties concerning the appropriateness of studies for inclusion in the review were resolved through consultation with a third review author (CD).

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (MF, NH and SG) extracted data independently using a data extraction form and entered data into RevMan 5 (RevMan 2008). Where data were not available in the published trial reports, we contacted the authors and asked them to supply the missing information. We made significant efforts to contact the primary trial investigator for missing data on any subgroup of participants diagnosed with AsPD where this was not published. If these data were made available to us, we included the data in the review. If data were not forthcoming, we attempted to contact at least one of the co-investigators. A reasonable length of time (eight weeks) was allowed for the investigator(s) to supply the missing data before we proceeded with the analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each included study, two review authors (MF and NH) independently completed the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2008, section 8.5.1) with any disagreement resolved through consultation with a third review author (SG). We assessed the degree to which:

the allocation sequence was adequately generated (‘sequence generation’);

the allocation was adequately concealed (‘allocation concealment’);

knowledge of the allocated interventions was adequately prevented during the study (‘blinding’), whilst acknowledging that it is generally not possible to blind participants in trials of this nature;

incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed;

reports of the study were free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting; and

the study was apparently free of other problems that could put it at high risk of bias.

We allocated each domain one of three possible categories for each of the included studies: ‘Yes’ for low risk of bias, ‘No’ for high risk of bias, and ‘Unclear’ where the risk of bias was uncertain or unknown.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous (binary) data, we used the odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval to summarise results within each study. The odds ratio is chosen because it has statistical advantages relating to its sampling distribution and its suitability for modelling, and because it is a relative measure and so can be used to combine studies.

For continuous data, such as the measurement of impulsiveness on a scale, we compared the mean score for each outcome as determined by a standardised tool between the two groups to give a mean difference (MD), again with a 95% confidence interval. Where possible, we made these comparisons at specific follow-up periods: (1) within the first month, (2) between one and six months, and (3) between six and 12 months. Where possible, we presented endpoint data. Where both endpoint and change data were available for the same outcomes, then we only reported the former.

We reported continuous data that are skewed in a separate table, and did not calculate treatment effect sizes to minimise the risk of applying parametric statistics to data that depart significantly from a normal distribution. We define skewness as occurring when, for a scale or measure with positive values and a minimum value of zero, the mean is less than twice the standard deviation (Altman 1996). We summarised change-from-baseline (‘change score’) data along-side endpoint data where these were available. Change-from-baseline data may be preferred to endpoint data if their distribution is less skewed, but both types may be included together in meta-analysis (Higgins 2008, page 270). Where the data were insufficient for meta-analysis, we reported the results of the trial investigators’ own statistical analyses comparing treatment and control conditions using change scores.

In any meta-analysis, we intended to use the mean difference (MD) where the same outcome measure was reported in more than one study and the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different outcome measures of the same construct had been reported.

Unit of analysis issues

(a) Cluster-randomised trials

See Table 4 for information about future updates of this review.

Table 4. Additional methods for future updates.

| Issue | Method |

|---|---|

| Cluster-randomised trials | Where trials use clustered randomisation, study investigators may present their results after appropriately controlling for clustering effects (robust standard errors or hierarchical linear models). If, however, it is unclear whether a cluster-randomised trial has used appropriate controls for clustering, we will contact the study investigators for further information. If appropriate controls were not used, we will request individual participant data and re-analysed these using multilevel models which control for clustering. Following this, effect sizes and standard errors will be meta-analysed in RevMan5 using the generic inverse method (Higgins 2008). If appropriate controls were not used and individual participant data are not available, we will seek statistical guidance from the Cochrane Methods Group and external experts as to which method to apply to the published results in attempt to control for clustering. If there is insufficient information to control for clustering, outcome data will be entered into RevMan5 using the individual as the unit of analysis, and then sensitivity analysis used to assess the potential biasing effects of inadequately controlled clustered trials (Donner 2001). |

| Missing data | The standard deviations of the outcome measures should be reported for each group in each trial. If these are not given, we will impute standard deviations using relevant data (for example, standard deviations or correlation coefficients) from other, similar studies (Follman 1992) but only if, after seeking statistical advice, to do so is deemed practical and appropriate Assessment will be made of the extent to which the results of the review could be altered by the missing data by, for example, a sensitivity analysis based on consideration of ’best-case’ and ’worst-case’ scenarios (Gamble 2005). Here, the ’best-case’ scenario is that where all participants with missing outcomes in the experimental condition had good outcomes, and all those with missing outcomes in the control condition had poor outcomes; the ’worst-case’ scenario is the converse (Higgins 2008, section 16.2.2). We will report data separately from studies where more than 50% of participants in any group were lost to follow up. Where meta-analysis is undertaken, we will assess the impact of including studies with attrition rates greater than 50% through a sensitivity analysis. If inclusion of data from this group results in a substantive change in the estimate of effect of the primary outcomes, we will not add the data from these studies to trials with less attrition and will present them separately Any imputation of data will be informed, where possible, by the reasons for attrition where these are available. We will interpret the results of any analysis based in part on imputed data with recognition that the effects of that imputation (and the assumptions on which it is based) can have considerable influence when samples are small |

| Assessment of heterogeneity | We will consider I2 values less than 30% as indicating low heterogeneity, values in the range 30% to 70% as indicating moderate heterogeneity, and values greater than 70% as indicating high heterogeneity. We will make an attempt to identify any significant determinants of heterogeneity categorised at moderate or high |

| Assessment of reporting biases | We will draw funnel plots (effect size versus standard error) to assess publication bias. Asymmetry of the plots may indicate publication bias, although they may also represent a true relationship between trial size and effect size. If such a relationship is identified, we will further examine the clinical diversity of the studies as a possible explanation (Egger 1997). |

| Data synthesis and length of follow up | We will group outcome measures by length of follow up, and use the weighted average of the results of all the available studies to provide an estimate of the effect of psychological interventions for people with antisocial personality disorder. We will use regression techniques to investigate the effects of differences in study characteristics on the estimate of the treatment effects. We will seek statistical advice before attempting meta-regression. If meta-regression is performed, it will be executed using a random-effects model |

| Subgroup analysis | We will undertake subgroup analysis to examine the effect on primary outcomes of:

|

| Sensitivity analysis | We will undertake sensitivity analyses to investigate the robustness of the overall findings in relation to certain study characteristics. A priori sensitivity analyses are planned for:

|

(b) Multi-arm trials

All eligible outcome measures for all trial arms were included in this review.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact the original investigators to request any missing data and information on whether or not it can be assumed to be ‘missing at random’. For dichotomous data, we report missing data and drop-outs for each included study and report the number of participants who are included in the final analysis as a proportion of all participants in each study. We provide reasons for the missing data in the narrative summary where these are available. For missing continuous data, we provide a qualitative summary. See Table 4 for information about future updates of this review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We aimed to assess the extent of between-trial differences and the consistency of results of any meta-analysis in three ways: by visual inspection of the forest plots, by performing the Chi2 test of heterogeneity (where a significance level less than 0.10 is interpreted as evidence of heterogeneity), and by examining the I2 statistic (Higgins 2008; section 9.5.2). The I2 statistic describes approximately the proportion of variation in point estimates due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. See Table 4 for information about future updates of this review.

Assessment of reporting biases

See Table 4 for information about future updates of this review.

Data synthesis

We had planned to use meta-analyses to combine comparable outcome measures across studies. In carrying out meta-analysis, the weight given to each study is the inverse of the variance so that the more precise estimates (from larger studies with more events) are given more weight. See Table 4 for information about future updates of this review.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

See Table 4 for information about future updates of this review.

Sensitivity analysis

See Table 4 for information about future updates of this review.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

We carried out electronic searches over two consecutive time periods to minimise the difficulty of managing large numbers of citations. Searches to December 2006 produced in excess of 10,000 records. From inspection of titles and abstracts we identified 70 citations that appeared to describe randomised studies on psychological interventions for personality disorder. Twenty-one of these appeared to include participants with a diagnosis of antisocial or dissocial personality disorder (PD). Searches from December 2006 to September 2009 produced 6398 records. After excluding studies that focused exclusively on borderline PD, we identified 38 citations that appeared to describe randomised trials on psychological interventions for personality disorder. Twenty-seven of these had the potential to have included participants with a diagnosis of antisocial or dissocial PD. Full copies were obtained of the 48 records of studies where all or part of the sample appeared to meet diagnostic criteria for antisocial or dissocial PD.

Included studies

Of the 48 studies, we identified 11 that fully met the inclusion criteria. Ten included participants with antisocial personality disorder (under DSM criteria). One study (Tyrer 2004) included participants with dissocial personality disorder (under ICD-10 criteria). Data on participants with antisocial personality disorder (AsPD)were available for five of the 11 studies (Davidson 2009; Huband 2007; Messina 2003; Neufeld 2008; Woodall 2007) and these are summarised in this review. Data on the subgroup of participants with antisocial (or dissocial) PD from the other six studies (Ball 2005; Havens 2007; Marlowe 2007; McKay 2000; Tyrer 2004; Woody 1985) were not available at the time this review was prepared.

The 11 included studies involved a total of 14 comparisons of a psychological intervention against a relevant control condition (i.e. treatment as usual, waiting list or no treatment). There were some important differences between the studies. We summarise these differences and the main characteristics below. Further details are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Only three of the included studies addressed the primary outcomes defined in this review. Two studies reported on reconviction (Marlowe 2007; Woodall 2007) and one reported on aggression (Davidson 2009).

Design

Ten of the 11 studies were parallel trials with allocation by individual participant, and one (Havens 2007) was a cluster-randomised trial where the unit of allocation was treatment site. The 10 parallel trials included one two-condition comparison (Woody 1985) and one three-condition comparison (Messina 2003) against a control group.

Sample sizes

There was some variation in sample size between studies. Overall, 411 participants with antisocial or dissocial PD were randomised in the nine trials where this allocation was reported unambiguously, with the size of sample ranging from 15 to 100 (mean 45.7; SD 24.8). However, data were available to us for only five of these trials. In these, 276 participants with antisocial or dissocial PD were randomised, and sample size ranged from 24 to 100 (mean 55.2; SD 27.6). The number of participants completing was reported in only four studies where the proportion that completed ranged from 78.8% to 100% (mean 89.1%).

Setting

Three studies were carried out in the UK (Davidson 2009; Huband 2007; Tyrer 2004); the remaining eight took place in North America (Ball 2005; Havens 2007; Marlowe 2007; Messina 2003; McKay 2000; Neufeld 2008; Woodall 2007; Woody 1985). Five were multi-centre trials: Davidson 2009 with two sites; Havens 2007 with 10 sites; Huband 2007 with five sites; Messina 2003 with two sites; and Tyrer 2004 with five sites. Nine studies took place in an outpatient or community setting, and two (Marlowe 2007; Woodall 2007) in a prison or custodial environment. None were carried out in a hospital inpatient setting.

Participants

Participants were restricted to males in three studies (Davidson 2009; McKay 2000; Woody 1985). The remaining eight studies had a mix of male and female participants. With one exception (Tyrer 2004), all studies randomised more men than women. The overall mix was 79.9% men as compared to 20.1% women. All eleven studies involved adult participants, with the mean age per study ranging between 25.1 and 43.5 years (average 34.9 years).

Eight studies focused on participants with substance misuse difficulties. For these, inclusion criteria included opioid substance dependence disorder (Neufeld 2008; Woody 1985), cocaine dependence disorder (Messina 2003; McKay 2000), sentenced for driving whilst intoxicated (Woodall 2007), recent alcohol/drug use whilst homeless (Ball 2005), sentenced for a drug-related offence (Marlowe 2007), and being an intravenous drug user (Havens 2007). The remaining three studies did not recruit participants on the basis of substance misuse. For these, the focus was on recurrent self-harm (Tyrer 2004), violence (Davidson 2009) and meeting DSM-IV criteria for (any) personality disorder (Huband 2007).

Only two of the 11 studies focused exclusively on participants with a diagnosis of antisocial PD (Davidson 2009; Neufeld 2008). For the remaining nine, participants with antisocial or dissocial PD formed a subgroup. The size of this antisocial subgroup ranged from 15 to 52 participants, representing 3.1% to 46.1% respectively of the total sample (mean 28.5%). Data on the antisocial subgroup were available to us for only three (Huband 2007; Messina 2003; Woodall 2007) of these nine studies.

The precise definition of antisocial personality disorder and the method by which it was assessed varied between the studies. Six used DSM-IV criteria and made assessments using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Axis II disorders (SCID-II) (Davidson 2009; Havens 2007; Messina 2003), an ‘antisocial PD interview’ developed by the investigators from the SCID-II (Marlowe 2007), the International Personality Disorder Examination (Huband 2007), or the Personality Disorder Questionnaire (Ball 2005). Three studies used DSM-III-R criteria and assessed using the SCID-II (McKay 2000; Neufeld 2008), or the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (Woodall 2007). One earlier study used DSM-III criteria and made assessments using the Schedule for Affective Disorders & Schizophrenia and the Maudsley Personality Inventory (Woody 1985). One study used ICD-10 criteria and assessed using the PAS-Q (Tyrer 2004).

Ethnicity of participants was not always reported. Where it was, the proportion of the sample described by the investigators as either ‘white’ or ‘Caucasian’ ranged from 7% to 67% per study. The total number of white participants randomised expressed as a proportion of total randomised was 58% for those studies where this information was available. Taking just the studies from which data could be extracted for participants with antisocial or dissocial PD, the proportion of the sample described as either ‘white’ or ‘Caucasian’ ranged from 31% to 67% per study. Overall, 63% of all participants randomised were described as neither ‘white’ nor ‘Caucasian’.

Interventions

The following types of interventions were represented: behaviour therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, schema therapy, and social problem-solving therapy. Interventions that were group-based may have included elements of group psychotherapy, depending on how group psychotherapy is defined. None of the 11 studies evaluated psychodynamic psychotherapy, therapeutic community treatment, dialectical behaviour therapy, cognitive analytic therapy, mentalisation-based therapy or nidotherapy.

Eleven different psychological interventions were compared to a control condition. Full details are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table but can be summarised as follows and in Table 5 below.

Table 5. Details of the psychological interventions examined in the 11 included studies.

| Intervention | Description |

|---|---|

|

CBT + standard maintenance

Messina 2003 |

CBT is a structured intervention based on behavioural principles with positive verbal reinforcement of decreased or no use of illicit drugs, or for prosocial behaviour). Comprises 48 group sessions of 90 minutes (three per week for 16 weeks) with typically four to eight participants in each group. Participants continue on standard maintenance treatment (including methadone, mean 72 mg/day) |

|

Supportive-expressive psychotherapy + standard maintenance

Woody 1985 |

Supportive-expressive psychotherapy is an analytically-oriented focal psychotherapy. Standard maintenance is an individual counselling intervention focused on providing external services rather than dealing with intra-psychic processes, plus methadone maintenance |

|

Dual-focus schema therapy

Ball 2005 |

Dual focus schema therapy is a 24-week manual-guided individual therapy that integrates symptom-focused relapse prevention coping skills techniques with schema-focused techniques for early maladaptive schemas and coping styles |

|

Contingency management + standard maintenance

Neufeld 2008 Messina 2003 |

Neufeld 2008: Contingency-based behavioural programme is a highly structured contingency-based, adaptive treatment protocol comprising counselling sessions and behavioural interventions. Drug abstinence and counselling attendance are rewarded by greater control over methadone management with negative reinforcers being a reduction in methadone dosage and control of the dosage. Standard maintenance comprises standard methadone substitution treatment with two individual counselling sessions per week with bi-weekly reviews; negative drug screens are rewarded with methadone take home doses Messina 2003: Contingency management + standard maintenance comprises a brief meeting (two to five minutes) with a contingency management technician. Clean urine specimens are rewarded with vouchers of escalating value (to a maximum of $1277. 50 if drug-free for the 16 weeks of the trial) and with praise/encouragement. Positive samples result in the vouchers being with-held but the participant is not rebuked or punished. Participants continue on standard maintenance treatment (including metha-done, mean 62 mg/day) |

|

Individualised relapse prevention aftercare

McKay 2000 |

Individualised relapse prevention is a manualised modular intervention for substance users in the maintenance phase of recovery. Risky situations are identified and improved coping responses encouraged. Clients receive one individual relapse prevention session and one group session per week for up to 20 weeks |

|

Strengths-based case management

Havens 2007 |

Strengths-based case management includes engagement, strengths assessment, personal case planning, and resource acquisition. Services provided by case managers include advice on referrals to health and social services, and on transportation and employment |

|

Optimal judicial supervision

(Marlowe 2007) |

Optimal (’matched’) schedule of court hearings in which frequency of court attendance is matched with risk, so that high-risk offenders (those with AsPD and a history of drug treatment) attend with greater frequency. Group sessions were psychoeducational and covered a range of topics including relapse prevention strategies |

|

’Driving Whilst Intoxicated program’ + incarceration

Woodall 2007 |

The ’Driving Whilst Intoxicated program’ is non-confrontational and utilises a psychoeducational approach on the harmful effects of alcohol, stress management, and a work release programme for those in employment. It also incorporated culturally appropriate elements (71% of participants were native American). The programme was delivered whilst participants were subject to 28 days incarceration |

|

CBT + treatment as usual

Davidson 2009 Tyrer 2004 |

Davidson 2009: CBT involves a cognitive formulation of the individual’s problems (to promote engagement) and therapy focusing on beliefs about self and others that impair social functioning. Individuals were offered 15 or 30 sessions of CBT (to determine the optimal ’dose’) and therapist adherence/competence was assessed for a random selection (30%) of sessions by audio recording and found to be ”within competent range”. Tyrer 2004: Manual-assisted cognitive behaviour therapy (MACT) is a treatment for self-harming behaviour where participants are provided with a booklet based on CBT principles plus an offer of five plus two booster sessions of CBT in the first three months |

|

Social problem-solving therapy with psychoeducation

Huband 2007 |

An individual psychoeducation programme followed by 16 weekly group-based problem-solving sessions (lasting approximately two hours) based on the ’Stop and Think!’ method. Groups start with no more than eight participants in each and are single gender. |

Single modality interventions focused on substance misuse difficulties

CBT + standard maintenance (Messina 2003 for outpatients with cocaine dependence; Woody 1985 for male outpatients with opioid dependence, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup).

Supportive-expressive psychotherapy + standard maintenance (Woody 1985 for male outpatients with opioid dependence, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup).

Dual-focus schema therapy (Ball 2005 for homeless adults with substance abuse, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup).

Complex interventions focused on substance misuse difficulties

Contingency management + standard maintenance (Neufeld 2008 and Messina 2003, both for outpatients with cocaine dependence).

Contingency management + CBT + standard maintenance (Messina 2003 for outpatients with cocaine dependence).

Individualised relapse prevention aftercare (McKay 2000 for male outpatients with cocaine dependence, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup).

Strengths-based case management (Havens 2007 for intravenous drug-using outpatients, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup).

Optimal judicial supervision (Marlowe 2007 for adult drug court offenders, but with no data available for the AsPD subgroup).

‘Driving Whilst Intoxicated program’ + incarceration (Woodall 2007 for incarcerated drink-driving offenders with AsPD).

Single modality interventions not focused on substance misuse difficulties

CBT + treatment as usual (Davidson 2009 for male outpatients with AsPD and recent verbal/physical violence; Tyrer 2004 for outpatients with recurrent self-harm, but with no data available for the dissocial PD subgroup).

Social problem-solving therapy with psychoeducation (Huband 2007 for community-living adults with personality disorder and an AsPD subgroup).

It is important to note that participants allocated to the experimental condition in these studies commonly received some degree of treatment as usual in addition to the intervention under evaluation. It could be argued that the presence of such ‘treatment’ requires single modality interventions to be reclassified as complex. For example, standard maintenance for participants with opioid dependence commonly includes counselling sessions in addition to methadone maintenance, which could be seen as introducing an additional CBT component. We have, however, chosen to regard single modality interventions as uncontaminated by any ‘treatment as usual’ providing that similar ‘treatment as usual’ forms the control condition.

The duration of the interventions (excluding the very short intervention described by Havens 2007) ranged between four and 52 weeks (mean 23.5 weeks; median 24 weeks). Seven studies followed up participants beyond the end of the intervention period by, on average, 30.9 weeks (range four to 104 weeks).

Control conditions

The inclusion criteria required a control condition that was either treatment as usual, waiting list or no treatment (see Types of studies). We considered that all 11 studies had a control condition that could be described as treatment as usual (TAU). This decision was straightforward for six of the 11 studies, as follows. For Davidson 2009 and Tyrer 2004 it was clear that TAU simply comprised whatever treatment the participants would have received had the trial not taken place. For Huband 2007, treatment as usual pertained whilst on a wait-list for the intervention under evaluation. Treatment as usual was incarceration in Woodall 2007, passive referral in Havens 2007 and standard (‘unmatched’) schedule court hearings in Marlowe 2007.

For the remaining five studies, all of which focused on participants with substance misuse difficulties, we were forced to consider carefully whether the control condition was treatment as usual or an intervention in its own right. In each case we concluded that the control condition could properly be described as TAU because it represented what a treatment-seeking participant with similar substance misuse problems would normally experience had the trial not taken place. The control conditions for these five studies can be summarised:

Ball 2005: up to three sessions per week of group counselling and psychoeducation sessions plus standard methadone maintenance where appropriate, which the trial investigators described as ‘standard group substance abuse counselling’.

Messina 2003: one counselling session per fortnight, standard methadone maintenance, case management visits and medical care, which the trial investigators described as ‘methadone maintenance only’.

Neufeld 2008: two individual counselling sessions per week with standard methadone maintenance treatment, which the trial investigators described as ‘standard methadone substitution treatment’.

Woody 1985: standard drug counselling, which the investigators described as ‘a standard individual counselling intervention focused on providing external services rather than dealing with intra-psychic processes’, plus standard methadone maintenance.

McKay 2000: two group therapy sessions per week based on addictions-counselling and 12-step recovery practices, which the trial investigators described as ‘standard continuing care treatment’.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

One study included self-reported aggression as an outcome: Davidson 2009 summarised the number of participants reporting any incident of physical or verbal aggression, as measured with the MacArthur Community Violence Screening Instrument (MCVSI) interview, plus additional questions on four other behaviours (shouting angrily at others; threatening harm to others; causing damage to property; self-harm).

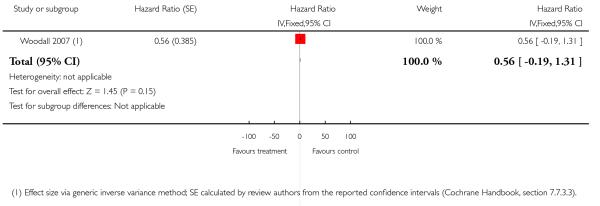

Two studies included reconviction as an outcome: Woodall 2007 reported drink-driving reconviction using data from the New Mexico State Citation Tracking System, and Marlowe 2007 assessed re-arrests and convictions using state criminal justice databases (although with no data available for the subgroup with AsPD).

Adverse effects, which are generally reported only rarely in studies of psychological interventions, were mentioned only by Marlowe 2007 where the investigators noted the absence of any study-related adverse events.

Four studies included self-reported social functioning as an outcome. Both Davidson 2009 and Huband 2007 reported mean scores on the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ). Neufeld 2008 reported composite scores on the family/social domain of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), and Ball 2005 reported scores using the same measure but with no data available for the subgroup with AsPD. The ASI is a semi-structured interview designed to assess problem severity in seven areas commonly affected by substance misuse difficulties, one of which is termed the family/social domain. Investigators obtained composite scores for this domain ranging from zero to 1.0 and based on problems reported in the last 30 days. Other domains relevant to this review are those concerning alcohol use, drug use and employment problems (see paragraph below on secondary outcomes).

There were five studies that did not report on any of the primary outcomes defined in the protocol for this review (Havens 2007; McKay 2000; Messina 2003; Tyrer 2004; Woody 1985); of these, only Messina 2003 had data available for participants with AsPD.

Secondary outcomes

Studies varied widely in their choice of secondary outcomes. Seven reported on leaving the study early, measuring this as the proportion of participants discontinuing treatment before endpoint. Three had data available for participants with AsPD (Davidson 2009; Messina 2003; Neufeld 2008). The remaining four had no data available for the AsPD subgroup (Ball 2005; Marlowe 2007; McKay 2000; Woody 1985). The mean number of continuing care sessions attended was additionally reported by McKay 2000. Only Davidson 2009 examined satisfaction with treatment as an outcome: the investigators used a semi-structured interview to enquire about ‘satisfaction with taking part in study’ and rated responses on a Likert scale from 1 to 7.

One study considered employment status: Neufeld 2008 reported mean composite scores on the employment domain of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI).

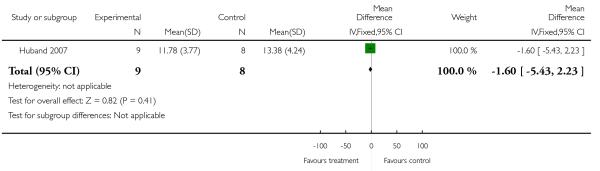

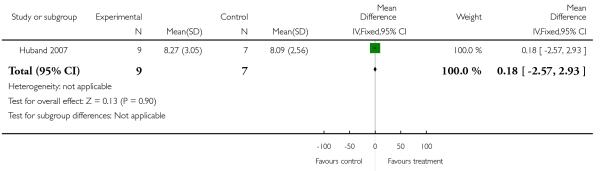

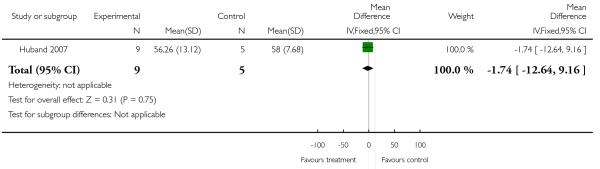

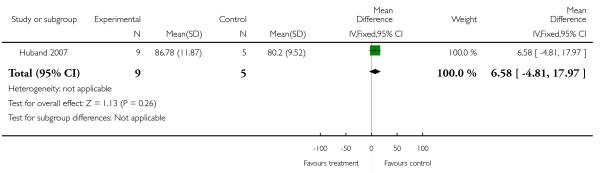

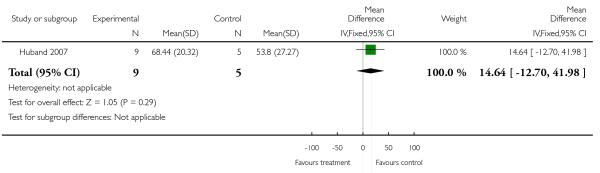

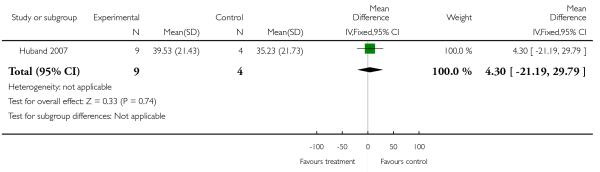

One study (Huband 2007) measured self-reported impulsivity using mean scores on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS).

Economic outcomes were considered by two studies: Davidson 2009 examined the total cost per participant of healthcare, social care and criminal justice services measured using case records and the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI); Tyrer 2004 calculated as total costs per participant, including costs incurred by all service-providing sectors and productivity losses resulting from time off work due to illness, although with no data available for the subgroup with dissocial PD.

Two studies included a self-reported measure of anger: Davidson 2009 provided mean scores on the NOVACO Scale and Provocation Inventory (NAS-PI), and Huband 2007 provided mean anger expression index scores using the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI-2).

To aid interpretation, ‘substance misuse’ was considered as two separate outcomes (see section on Differences between protocol and review). Substance misuse (drugs) was examined in six studies using the drug use domain of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (Marlowe 2007; McKay 2000; Neufeld 2008; Woody 1985), using the Cocaine Relapse Interview (CRI) (McKay 2000), and through urinalysis (Marlowe 2007; McKay 2000, Messina 2003; Neufeld 2008). Substance misuse (alcohol) was examined by three studies using the alcohol use domain of the Addiction Severity Index (Neufeld 2008), using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Davidson 2009), and via the Form 90 (a time-line follow-back self-report method to assess drinking over the previous 90 days) and the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC-2R) (Woodall 2007). In addition, Woodall 2007 reported the frequency of drink-driving in 30 days prior to arrest, or in previous 30 days, measured via questionnaire.

The outcome of engagement with services was considered only by Havens 2007 where the investigators report numbers entering into drug addiction treatment services as a key outcome, although with no data available for the AsPD subgroup.

No study reported on quality of life.

Other relevant outcomes

Psychiatric symptoms were measured in several studies: depression scores were reported using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) by Woody 1985; both anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Rating Scale (HADS) by Davidson 2009; or generally using the Symptoms Checklist (SCL90) (Woody 1985) or the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (Ball 2005). Huband 2007 reported on shame using the Experience of Shame Scale (ESS), on dissociation using the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES), and on social problem-solving ability via Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R). Ball 2005 reported on interpersonal problems via the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP), on severity of PD via the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (PDQ), and on schemas via scores on Early Maladaptive Schema Questionnaire-Research (EMSQ-R). Davidson 2009 reported on schemas using the Brief Core Schema Scales (BCSS). Tyrer 2004 reported number of completed suicides and frequency of self-harm episodes via the Parasuicide History Interview (PHI). Finally, therapy retention was measured as total weeks in treatment (Ball 2005), as adherence to counselling sessions (Neufeld 2008) or as the proportion therapeutically transferred over to routine care due to poor/partial treatment response in response to ongoing drug use or poor attendance to scheduled services (Neufeld 2008).

Studies awaiting classification

We identified three studies of psychological treatments for samples with a mixture of personality disorders where it remains unclear whether a subgroup of participants with a diagnosis of antisocial or dissocial PD had been included (Berget 2008; Evans 1999; Linehan 2006). Clarification has been sought from the trial investigators but no further information was available at the time this review was prepared. Details are provided in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. These may be summarised as follows.

Berget 2008 compared animal-assisted therapy with a control condition in individuals with psychiatric disorders, and may have recruited a subgroup with dissocial PD since 22 of the 90 participants had a disorder diagnosed under sections F60-69 in ICD-10 (disorders of adult personality and behaviour).

Evans 1999 compared manualised cognitive therapy with treatment as usual in adults with recent self-harm and cluster B personality disturbance. The investigators may have recruited a subgroup with dissocial PD since, although formal Axis II diagnoses are not reported, all participants scored on the Personality Assessment Schedule at least to the level of personality disturbance within the flamboyant cluster of ICD-10.

Linehan 2006 compared DBT and community treatment by experts for adults with suicidal behaviour and BPD, and may have recruited a subgroup with AsPD since 11 of the 101 participants (10.9%) had at least one other cluster B personality disorder.

Excluded studies

The remaining 34 studies that failed to meet all inclusion criteria were categorised as excluded studies. Fifteen were excluded because on close inspection, and following translation into English and contact with the investigators where necessary, it became clear that the sample did not include a subgroup with antisocial or dissocial PD. A further six were excluded because there were less than five participants with antisocial or dissocial PD for reasons that are now explained in the Selection of studies section. Five were excluded because participants had not been allocated at random, and a further six because of lack of a relevant control condition. One study was excluded because it was a trial of assessment rather than of psychological treatment, and one because a proportion of the sample had bipolar disorder. Reasons for exclusion of each of these 34 studies are given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

We paid particular attention to five of the excluded studies (described in seven separate reports) that compared one psychological treatment against another. Each was excluded because there was no control condition that could be regarded as treatment as usual, waiting list or no treatment. Although none of these studies focused exclusively on AsPD, and none provided data on their AsPD subgroup, each reported information that we considered would be of interest to a clinician who was seeking treatment options for clients with AsPD. Because of this, we have summarised briefly the characteristics of each of these five studies and conclusions drawn by the trial investigators in the Discussion section.

Risk of bias in included studies

There was considerable variation in how the included studies were reported. We attempted to contact the investigators wherever the available trial reports provided insufficient information for decisions to be made about the likely risk of bias, and were successful in respect of four studies.

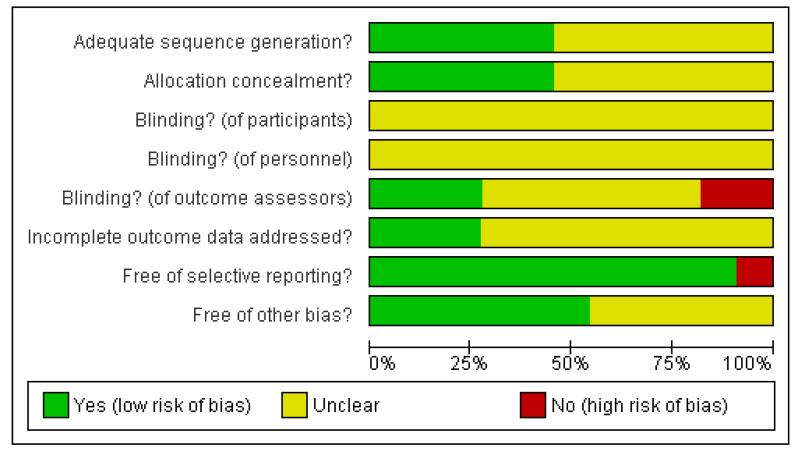

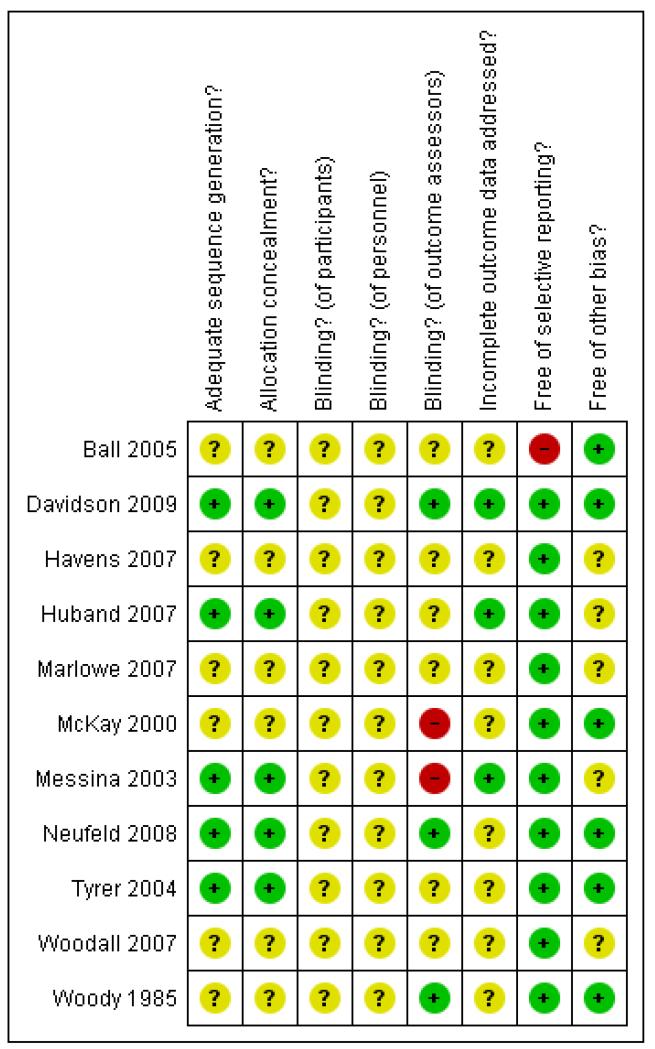

We summarise below the risk of bias for the 11 included studies. Studies with data that could be extracted for the antisocial or dissocial PD subgroup (n = 5) are summarised separately from those for which data were unavailable (n = 6). This allows the reader to make a separate judgement about possible bias associated with the quantitative data from which conclusions are drawn in this review. Full details of our assessment of the risk of bias in each case are tabulated within the Characteristics of included studies section. Graphical summaries of methodological quality are presented as Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

With data (five studies)

We considered the generation of allocation sequence to be adequate in three studies where allocation was by random numbers which were computer-generated (Davidson 2009; Huband 2007) or derived from a table (Messina 2003), and in one study where the toss of coin was used (Neufeld 2008). We classified adequacy of sequence generation as ‘unclear’ in the remaining study (Woodall 2007) where the investigators reported that participants had been allocated at random but provided no further information on how this had been achieved. We considered concealment of the allocation sequence adequate for Davidson 2009, Huband 2007, Neufeld 2008 and Messina 2003 where we considered that there was sufficient evidence that the person enrolling participants could not have foreseen assignment. We classified adequacy of sequence concealment as ‘unclear’ in the remaining study (Woodall 2007) because the information available was insufficient to allow a judgment to be made.

Without data (six studies)

We classified adequacy of sequence generation as adequate for Tyrer 2004 (computer-generated random numbers) but ‘unclear’ for the remaining five studies. In each case the investigators reported that participants had been allocated at random but provided no further information on how this had been achieved. We considered concealment of the allocation sequence adequate for Tyrer 2004. We classified adequacy of sequence concealment as ‘unclear’ in the remaining five studies, again because the information available was insufficient to allow a judgement to be made.

Blinding

We judged that blinding of participants and personnel involved in the delivery of the intervention was not practical in the design of trials of psychological interventions summarised in this review.

With data (five studies)

We considered adequacy of blinding of outcome assessors to be adequate in two studies (Davidson 2009; Neufeld 2008) and that it was unlikely that this blind could have been broken. In Messina 2003 the outcome assessors were not blinded. We classified two studies as ‘unclear’ because the information available was insufficient to allow a judgment to be made (Huband 2007; Woodall 2007).

Without data (six studies)

We judged adequacy of blinding of outcome assessors adequate for Woody 1985, not adequate for McKay 2000 and ‘unclear’ in the remaining four studies where there was insufficient information to allow a judgement to be made.

Incomplete outcome data

With data (five studies)

We judged none to have adequately addressed incomplete outcome data. We classified all five as ‘unclear’ because, although numbers balanced approximately between treatment conditions, the reasons for attrition were not available. This generally arose because participants failed to complete endpoint measures without providing a reason. Two of these five studies reported undertaking an intention-to-treat analysis for at least one primary or secondary outcome (Davidson 2009; Huband 2007) and three provided analysis only for those participants classed by the investigators as ‘completers’ (Messina 2003; Neufeld 2008; Woodall 2007).

Without data (six studies)

We classed all six studies as ‘unclear’ because it was not possible, in the absence of data from the subgroup with antisocial or dissocial PD, to judge the extent and nature of any missing data, and whether the reasons for such missing data balance across intervention groups.

The overall proportion of missing data (treatment and control conditions combined) varied significantly between studies. Missing data rates for the five studies with data were calculated as number with endpoint scores in comparison with number randomised and ranged from 8.3% to 29.2% (mean 18.0%; SD 7.8%; median 17.3%). Mean rates by type of intervention, calculated similarly, were as follows: CBT 18.2% (two studies); contingency management plus standard maintenance 13.0% (two studies); social problem-solving therapy with psychoeducation 29.2% (one study); DWI program with incarceration 17.3% (one study). These percentages should be regarded with caution for studies where the sample size is small.

Selective reporting

With data (five studies)

We judged that all five studies appeared to have reported on all the measures they set out to use and at all time scales in as far as could be discerned from the published reports without access to the original protocols.

Without data (six studies)

We classified all six studies as ‘unclear’ because it was not possible, in the absence of data from the subgroup with antisocial or dissocial PD, to judge whether there was selective reporting of any relevant data.

Other potential sources of bias

With data (five studies)

Messina 2003 report providing a reduction of $40 per month (representing a discount of between 22% and 29%) in the cost of methadone maintenance treatment as an incentive for participation in the study. Review authors classed this as ‘unclear’ because of uncertainty whether this could have introduced bias. We judged the remaining four studies free of other potential sources of bias.

Without data (six studies)

We classed Marlowe 2007 as ‘unclear’ because of uncertainty about possible risk of bias from diagnosis of AsPD using an ‘antisocial personality disorder interview’ derived from SCID-II by the trial investigators but with no information on its validation. Havens 2007 was classed as ‘unclear’ because, as the trial investigators acknowledged, selection bias may have been present because only those completing the one-month follow up were eligible for psychiatric assessment and participants in the case management arm were significantly less likely to have been followed up. We judged the remaining four studies free of other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

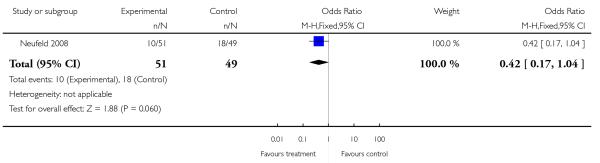

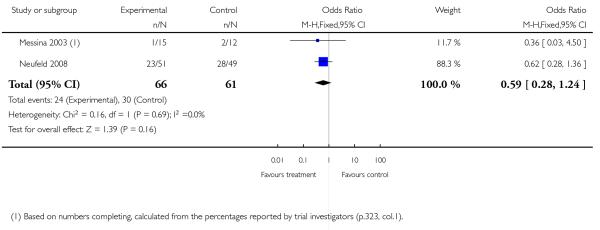

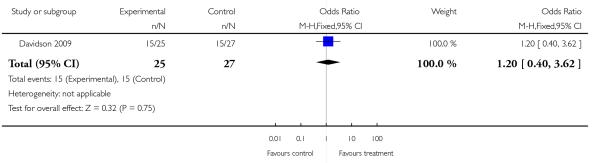

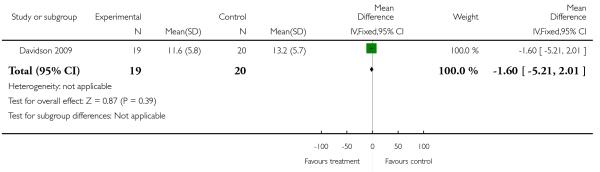

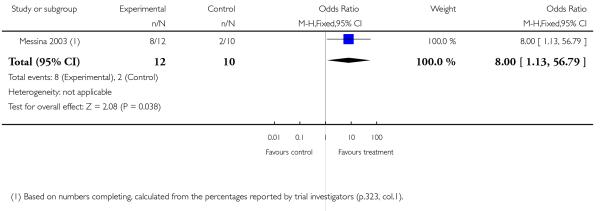

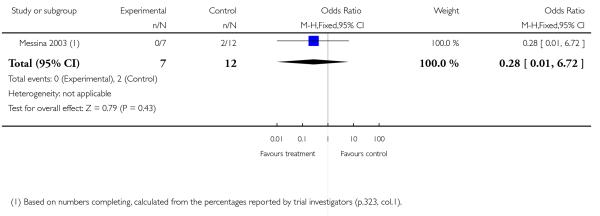

Comparison 1. Contingency management + standard maintenance versus standard maintenance alone

Two studies were included in this comparison: Neufeld 2008 (outpatients with AsPD and opioid dependence; six months treatment; n = 100) and Messina 2003 (outpatients with cocaine dependence; AsPD subgroup; 16 weeks treatment; n = 26).

1.1 Social functioning

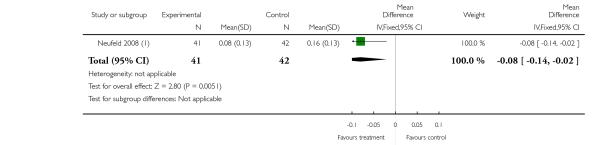

Neufeld 2008 report data indicating a statistically significant difference between treatment and control conditions in (adjusted) composite family/social domain scores via the Addiction Severity Index at six months favouring treatment (MD −0.08; 95% CI −0.14 to −0.02, P = 0.005, Analysis 1.3). This analysis is based on summary data of completers supplied by the trial investigators and derived from a mixed regression model that included time-specific random effects and an interaction term (see Table 1).

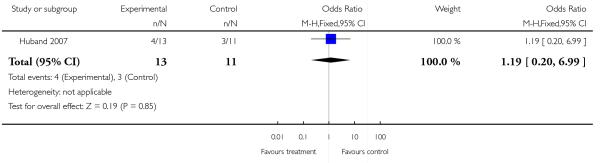

1.2 Leaving the study early

Both Neufeld 2008 and Messina 2003 provide data on leaving the study early. Meta-analysis of data from these two studies indicates no statistically significant difference between treatment and control conditions (OR 0.59; 95% CI 0.28 to 1.24, P = 0.16, I2 = 0%; P value for heterogeneity 0.69, Analysis 1.2).

1.3 Substance misuse (drugs)

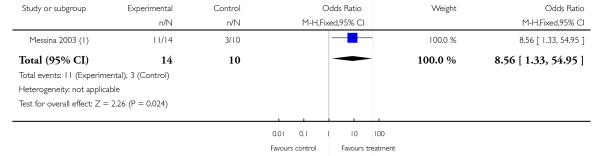

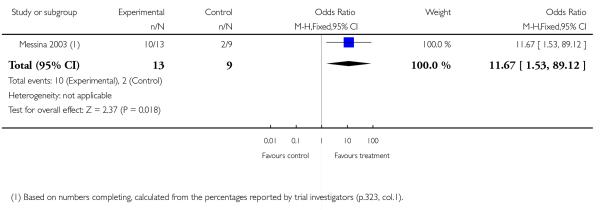

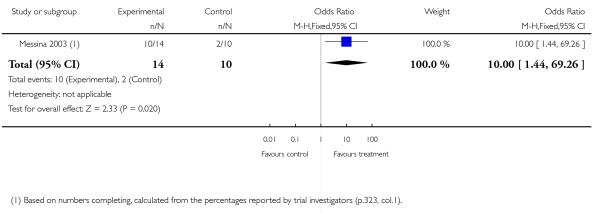

Messina 2003 report data indicating a statistically significant difference between treatment and the control condition in numbers with cocaine-negative specimens by week 17 (OR 8.56; 95% CI 1.33 to 54.95, P = 0.02, Analysis 1.4), by week 26 (OR 11.67; 95% CI 1.53 to 89.12, P = 0.01, Analysis 1.5), and by week 52 (OR 10.00; 95% CI 1.44 to 69.26, P = 0.02, Analysis 1.6), favouring treatment in each case. Messina 2003 also report skewed summary data (see Table 2) indicating a statistically significant greater mean number of cocaine-negative specimens for the treatment compared to the control condition by 16 weeks (P < 0.05; two-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test; analysis of completers by the trial investigators). The trial investigators conclude that “ … patients with AsPD were more likely to abstain from cocaine use during treatment than patients without AsPD. The strong treatment effect for AsPD patients was primarily due to the contingency management condition. Regression analyses showed that AsPD remained significantly related to contingency management treatment responsivity while controlling for other factors”. (Abstract, p.320, Messina 2003). Neufeld 2008 report data indicating no statistically significant difference between treatment and control conditions in (adjusted) mean composite drug domain scores via the Addiction Severity Index at six months (data presented graphically; hierarchical regression model with variables at one, two, three and six months including condition, time, time-by-condition interaction and polydrug use at baseline; analysis of completers by the trial investigators, see Table 1). Neufeld 2008 also report summary data (see Table 3) indicating no statistically significant difference between treatment and control conditions at six months for overall percentage of opioid-negative urine specimens (OR 1.31; 95% CI 0.71 to 2.42, P = 0.39), of cocaine-negative urine specimens (OR 1.59; 95% CI 0.86 to 2.96, P = 0.14), of sedative-negative urine specimens (OR 1.82; 95% CI 0.72 to 4.42, P = 0.18) and of negative urine specimens for any drug (OR 1.70; 95% CI 0.94 to 3.07, P = 0.08), each being an analysis of completers carried out by the trial investigators.

1.4 Substance misuse (alcohol)

Neufeld 2008 report data indicating no statistically significant difference between treatment and control conditions in (adjusted) mean composite alcohol domain scores via the Addiction Severity Index at six months (data presented graphically; hierarchical regression model with variables at one, two, three and six months including condition, time, time-by-condition interaction and polydrug use at baseline; analysis of completers by the trial investigators, see Table 1).

1.5 Employment status

Neufeld 2008 report data indicating no statistically significant difference between treatment and control conditions in (adjusted) mean composite employment domain scores via the Addiction Severity Index at six months (data presented graphically; hierarchical regression model with variables at one, two, three and six months including condition, time, time-by-condition interaction and polydrug use at baseline; analysis of completers by the trial investigators, see Table 1).

1.6 Other outcomes

Neufeld 2008 report summary data (see Table 4) indicating a greater, statistically significant, overall number of counselling sessions attended in proportion to the total number of sessions offered for treatment compared to the control condition by six months (OR 4.00, 95% CI 2.39 to 6.70, P < 0.0001; analysis of completers by the trial investigators). The trial investigators concluded that “subjects in the experimental group had significantly better counselling attendance … compared to the control group. The experimental intervention increased attendance in subjects with low and high levels of psychopathy and with and without other psychiatric co-morbidity.” (Abstract, p.101, Neufeld 2008).

Neufeld 2008 report data indicating no statistically significant difference between treatment and control conditions in the proportion of participants transferred due to poor or partial treatment response by six months (OR 0.42; 95% CI 0.17 to 1.04, P = 0.04, Analysis 1.1).

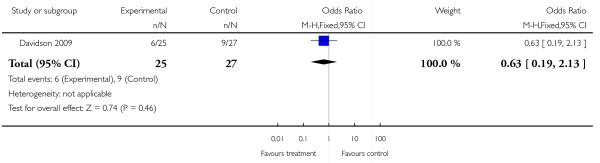

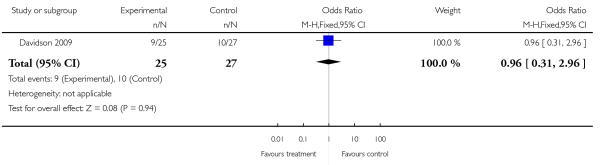

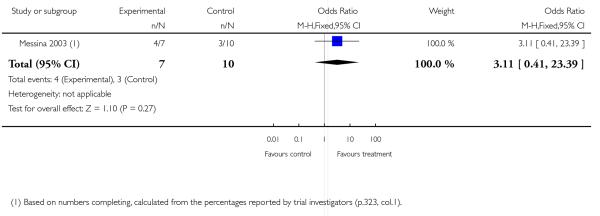

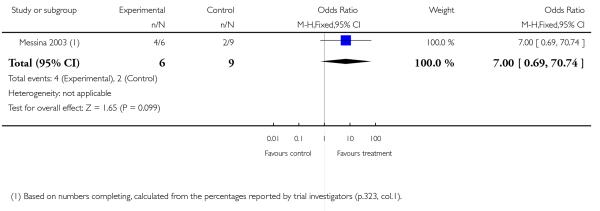

Comparison 2. CBT + standard maintenance versus standard maintenance alone

Two studies were included in this comparison: Messina 2003 (outpatients with cocaine dependence; AsPD subgroup; 16 weeks treatment; n = 27) and Woody 1985 (male outpatients with opioid dependence; 24 weeks treatment; n = 50; no data available for control condition for the AsPD subgroup).

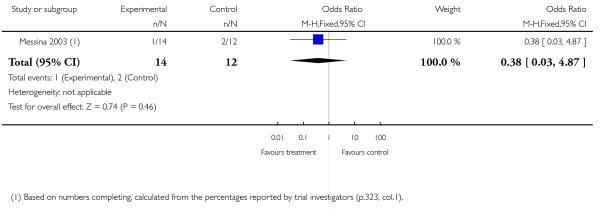

2.1 Leaving the study early

Messina 2003 report data indicating no statistically significant difference between treatment and control conditions for leaving the study early (OR 0.38; 95% CI 0.03 to 4.87, P = 0.46, Analysis 4.1). Woody 1985 provide data on leaving the study early, but with no data for the AsPD subgroup.

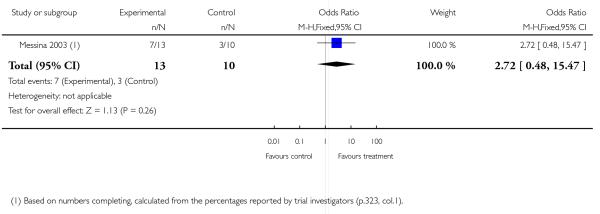

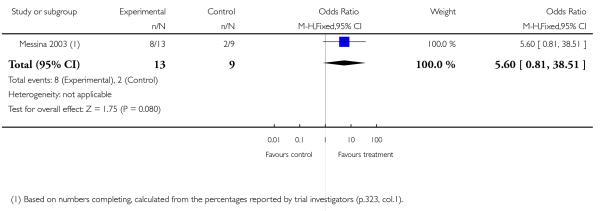

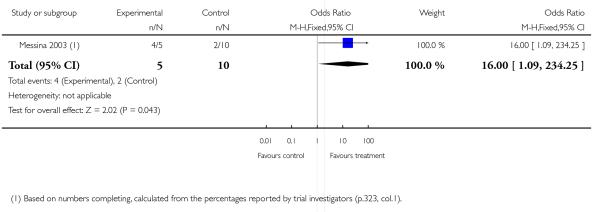

2.2 Substance misuse (drugs)

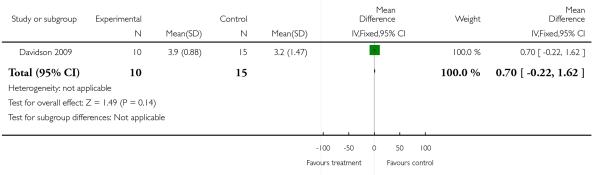

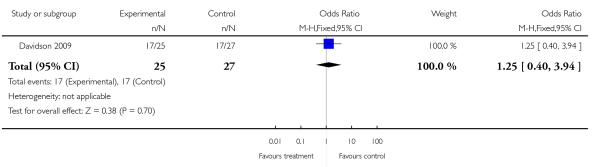

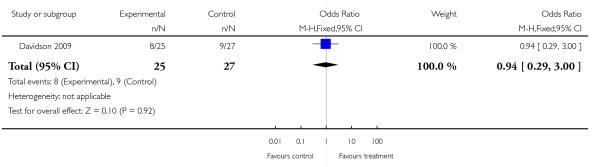

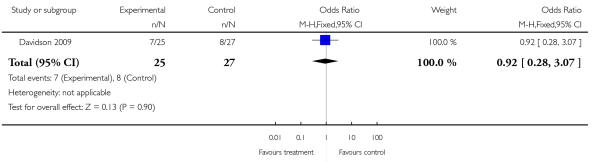

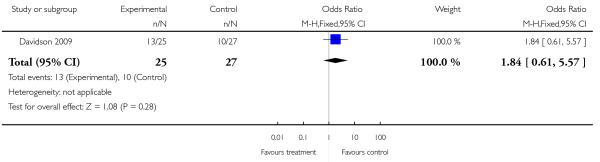

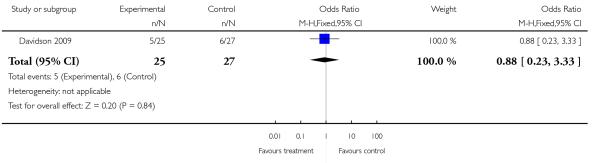

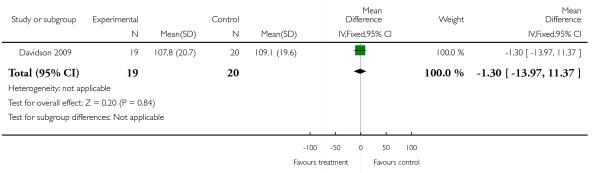

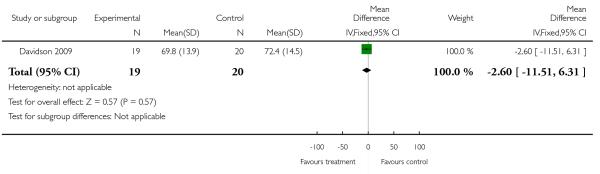

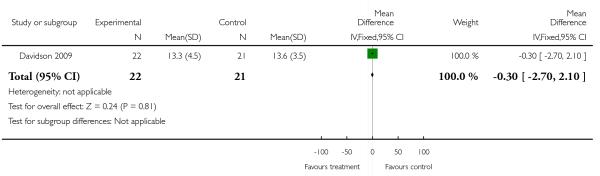

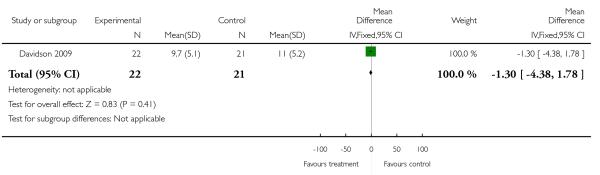

Messina 2003 report data indicating no statistically significant difference between treatment and control conditions in numbers with cocaine-negative specimens by week 17 (OR 2.72; 95% CI 0.48 to 15.47, P = 0.26, Analysis 4.2) and by week 26 (OR 5.60; 95% CI 0.81 to 38.51, P = 0.08, Analysis 4.3).