Abstract

Background

In many countries of the industrialised world second generation (’atypical’) antipsychotic drugs have become the first line drug treatment for people with schizophrenia. It is not clear how the effects of the various second generation antipsychotic drugs differ.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of quetiapine compared with other second generation antipsychotic drugs for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like psychosis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (April 2007), inspected references of all identified studies, and contacted relevant pharmaceutical companies, drug approval agencies and authors of trials for additional information.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised control trials comparing oral quetiapine with oral forms of amisulpride, aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, sertindole, ziprasidone or zotepine in people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like psychosis.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data independently. For dichotomous data we calculated relative risks (RR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) on an intention-to-treat basis based on a random-effects model. We calculated numbers needed to treat/harm (NNT/NNH) where appropriate. For continuous data, we calculated weighted mean differences (WMD) again based on a random-effects model.

Main results

The review currently includes 21 randomised control trials (RCTs) with 4101 participants. These trials provided data on four comparisons - quetiapine versus clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone or ziprasidone.

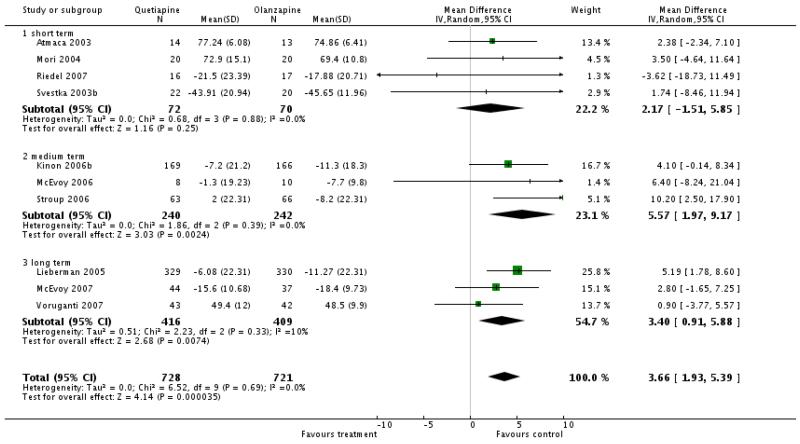

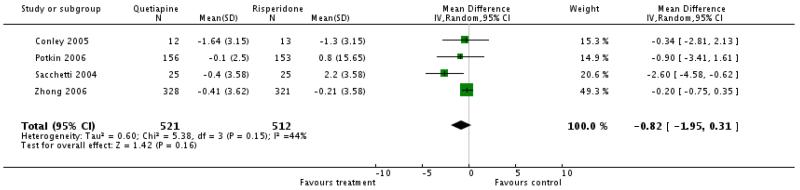

A major limitation to all findings is the high number of participants leaving studies prematurely (57.6%) and the substantial risk of biases in studies. Efficacy data favoured olanzapine and risperidone compared with quetiapine (PANSS total score versus olanzapine:10 RCTs, n=1449, WMD 3.66 CI 1.93 to 5.39; versus risperidone: 9 RCTs, n=1953, WMD 3.09 CI 1.01 to 5.16), but clinical meaning is unclear. There were no clear mental state differences when quetiapine was compared with clozapine or ziprasidone.

Compared with olanzapine, quetiapine produced slightly fewer movement disorders (6 RCTs, n=1090, RR use of antiparkinson medication 0.49 CI 0.3 to 0.79, NNH 25 CI 14 to 100) and less weight gain (7 RCTs, n=1173, WMD −2.81 CI −4.38 to −1.24) and glucose elevation, but more QTc prolongation (3 RCTs, n=643, WMD 4.81 CI 0.34 to 9.28). Compared with risperidone, quetiapine induced slightly fewer movement disorders (6 RCTs, n=1715, RR use of antiparkinson medication 0.5 CI 0.3 to 0.86, NNH 20 CI 10 to 100), less prolactin increase (6 RCTs, n=1731, WMD −35.28 CI −44.36 to −26.19) and some related adverse effects, but more cholesterol increase (5 RCTs, n=1433, WMD 8.61 CI 4.66 to 12.56). Compared with ziprasidone, quetiapine induced slightly fewer extrapyramidal adverse effects (1 RCT, n=522, RR use of antiparkinson medication 0.43 CI 0.2 to 0.93, NNH not estimable) and prolactin increase. On the other hand quetiapine was more sedating and led to more weight gain (2 RCTs, n=754, RR 2.22 CI 1.35 to 3.63, NNH 13 CI 8 to 33) and cholesterol increase than ziprasidone.

Authors’ conclusions

Best available evidence from trials suggests that most people who start quetiapine stop taking it within a few weeks. Comparisons with amisulpride, aripiprazole, sertindole and zotepine do not exist. Most data that has been reported within existing comparisons are of very limited value because of assumptions and biases within them. There is much scope for further research into the effects of this widely used drug.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Antipsychotic Agents [adverse effects; * therapeutic use], Benzodiazepines [adverse effects; therapeutic use], Clozapine [adverse effects; therapeutic use], Dibenzothiazepines [adverse effects; * therapeutic use], Medication Adherence [statistics & numerical data], Piperazines [adverse effects; therapeutic use], Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Risperidone [adverse effects; therapeutic use], Schizophrenia [* drug therapy], Thiazoles [adverse effects; therapeutic use]

MeSH check words: Humans

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia can be a disabling psychiatric disorder which afflicts approximately one per cent of the population world-wide with little gender differences. The annual incidence of schizophrenia averages 15 per 100,000, the point prevalence averages approximately 4.5 per population of 1000, and the risk of developing the illness over one’s lifetime averages 0.7% (Tandon 2008). Its typical manifestations are positive symptoms such as fixed, false beliefs (delusions) and perceptions without cause (hallucinations), negative symptoms such as apathy and lack of drive, disorganisation of behaviour and thought, and catatonic symptoms such as mannerisms and bizarre posturing (Carpenter 1994). The degree of suffering and disability is considerable with 80% - 90% not working (Marvaha 2004) and up to 10% dying (Tsuang 1978). In the 15-44 years age group, schizophrenia is among the top ten leading causes of disease-related disability in the world (WHO 2001). Conventional antipsychotic drugs, such as chlorpromazine and haloperidol, have traditionally been used as first line antipsychotic drugs for people with schizophrenia (Kane 1993). The reintroduction of clozapine in the USA, and findings to indicate that clozapine seemed more effective than other drugs, as well as being associated with fewer movement disorders than chlorpromazine (Kane 1988), boosted development of new/second/atypical generation antipsychotic drugs (SGA).

Description of the intervention

There is no good definition of what an ’atypical’ antipsychotic is, but they were initially said to differ from typical antipsychotic drugs in that they do not cause movement disorders (catalepsy) in rats at clinically effective doses (Arnt 1998). The terms ’new’ or ’second generation’ antipsychotic drugs are not much better, because clozapine is now a very old drug. According to treatment guidelines (APA 2004, Gaebel 2006) second generation antipsychotic drugs include drugs such as amisulpride, aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, ziprasidone and zotepine, although it is unclear whether some old and inexpensive compounds such as sulpiride or perazine have similar properties (Möller 2000). The second generation antipsychotic drugs raised major hopes of superior effects in a number of areas such as compliance, cognitive functioning, negative symptoms, movement disorders, quality of life, and the treatment of people whose illness had formerly been resistant to treatment.

How the intervention might work

Experimental laboratory studies have suggested that quetiapine is a clozapine-like atypical antipsychotic (Migler 1993, Goldstein 1993, Saller 1993). In contrast to olanzapine, risperidone, sertindole and ziprasidone have high affinities (<50 nM) to both D2 and 5-HT2A receptors, quetiapine is similar to clozapine in having only moderate affinities (<500 nM) to these sites (Goldstein 1995). Quetiapine has a high affinity for histamine receptors (<50 nM) (Srisurapanont 2004).

Why it is important to do this review

The debate as to how far the second generation antipsychotic drugs improve these outcomes compared with conventional antipsychotic drugs continues (Duggan 2005, El-Sayeh 2006) and the results from recent studies were sobering (Liebermann 2005, Jones 2006). Nevertheless, in some parts of the world, especially in the highly industrialised countries, second generation antipsychotic drugs have become the mainstay of treatment. They also differ in terms of their costs: while amisulpride and risperidone are already generic in many countries, quetiapine for example is still not. Therefore the question as to whether they differ from each other in their clinical effects becomes increasingly important. In this review we aim to summarise evidence from randomised controlled trials that compared quetiapine with other second generation antipsychotic drugs.

OBJECTIVES

To review the effects of quetiapine compared with other atypical antipsychotic drugs for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like psychosis.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included relevant randomised controlled trials which were at least single-blind (blind raters). Where a trial was described as double-blind, but it was only implied that the study was randomised, we included these trials in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantive difference within primary outcomes (see Types of outcome measures) when these implied randomisation studies were added, then we included these in the final analysis. If there was a substantive difference, we only used clearly randomised trials and described the results of the sensitivity analysis in the text. We excluded quasi-randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

We included randomised cross-over studies but only data up to the point of first cross-over because of the instability of the problem behaviours and the likely carry-over effects of all treatments.

Types of participants

We included people with schizophrenia and other types of schizophrenia-like psychosis (e.g. schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders), irrespective of the diagnostic criteria used. There is no clear evidence that the schizophrenia-like psychoses are caused by fundamentally different disease processes or require different treatment approaches (Carpenter 1994).

Types of interventions

Quetiapine: any oral form of application, any dose.

Other ’atypical’ antipsychotic drugs: amisulpride, aripiprazole, clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, sertindole, ziprasidone, zotepine: any oral form of application, any dose.

Types of outcome measures

We grouped outcomes into the short term (up to 12 weeks), medium term (13-26 weeks) and long term (over 26 weeks).

Primary outcomes

Global State: No clinically important response as defined by the individual studies (e.g. global impression less than much improved or less than 50% reduction on a rating scale)

Secondary outcomes

-

1

Leaving the studies early (any reason, adverse events, inefficacy of treatment)

-

2

Global state

-

2.1

No clinically important change in global state (as defined by individual studies)

-

2.2

Relapse (as defined by the individual studies)

-

3

Mental state (with particular reference to the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia)

-

3.1

No clinically important change in general mental state score

-

3.2

Average endpoint general mental state score

-

3.3

Average change in general mental state score

-

3.4

No clinically important change in specific symptoms (positive symptoms of schizophrenia, negative symptoms of schizophrenia)

-

3.5

Average endpoint specific symptom score

-

3.6

Average change in specific symptom score

-

4

General functioning

-

4.1

No clinically important change in general functioning

-

4.2

Average endpoint general functioning score

-

4.3

Average change in general functioning score

-

5

Quality of life/satisfaction with treatment

-

5.1

No clinically important change in general quality of life

-

5.2

Average endpoint general quality of life score

-

5.3

Average change in general quality of life score

-

6

Cognitive functioning

-

6.1

No clinically important change in overall cognitive functioning

-

6.2

Average endpoint of overall cognitive functioning score

-

6.3

Average change of overall cognitive functioning score

-

7

Service use

-

7.1

Admitted

-

8

Adverse effects

-

8.1

Number of people with at least one adverse effect

-

8.2

Clinically important specific adverse effects (cardiac effects, death, movement disorders, prolactin increase and associated effects, sedation, seizures, weight gain, effects on white blood cell count)

-

8.3

Average endpoint in specific adverse effects

-

8.4

Average change in specific adverse effects

Search methods for identification of studies

No language restriction was applied within the limitations of the search tools.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Specialised Register (April 2007) using the phrase: [((quetiapin* AND (amisulprid* OR aripiprazol* OR clozapin* OR olanzapin* OR risperidon* OR sertindol* OR ziprasidon* OR zotepin*)) in title, abstract or index terms of REFERENCE) or ((quetiapin* AND (amisulprid* OR aripiprazol* OR clozapin* OR olanzapin* OR risperidon* OR sertindol* OR ziprasidon* OR zotepin*)) in interventions of STUDY)]

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Group Module). The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register is maintained on Meerkat 1.5. This version of Meerkat stores references as studies. When an individual reference is selected through a search, all references which have been identified as the same study are also selected.

Searching other resources

Reference searching We inspected the references of all identified studies for more trials.

Personal contact We contacted the first author of each included study for missing information.

Drug companies We contacted the manufacturers of all atypical antipsychotic drugs included for additional data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

KK, CRK and SL independently inspected all reports. We resolved any disagreement by discussion, and where there was still doubt, we acquired the full article for further inspection. Once the full articles were obtained, we independently decided whether the studies met the review criteria. If disagreement could not be resolved by discussion, we sought further information and added these trials to the list of those awaiting assessment.

Data extraction and management

1. Data extraction

KK, CRK and SL independently extracted data from selected trials. When disputes arose we attempted to resolve these by discussion. When this was not possible and further information was necessary to resolve the dilemma, we did not enter data and added the trial to the list of those awaiting assessment.

2. Management

KK, CRK, FS, HH, SS and SL extracted data onto standard simple forms. Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for quetiapine.

3. Rating scales

A wide range of instruments are available to measure outcomes in mental health studies. These instruments vary in quality and many are not validated, or are even ad hoc. It is accepted generally that measuring instruments should have the properties of reliability (the extent to which a test effectively measures anything at all) and validity (the extent to which a test measures that which it is supposed to measure) (Rust 1989). Unpublished scales are known to be subject to bias in trials of treatments for schizophrenia (Marshall 2000). Therefore continuous data from rating scales were included only if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer-reviewed journal.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Again working independently, KK and SL assessed risk of bias using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). This tool encourages consideration of how the sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases.

The risk of bias in each domain and overall were assessed and categorised into:

Low risk of bias: plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results (categorised as ’Yes’ in Risk of Bias table)

High risk of bias: plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results (categorised as ’No’ in Risk of Bias table)

Unclear risk of bias: plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results (categorised as ’Unclear’ in Risk of Bias table)

Trials with high risk of bias (defined as at least four out of seven domains) were categorised as ’No’) or where allocation was clearly not concealed were not included in the review. If the raters disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus with the involvement of another member of the review group. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials are provided, authors of the studies were contacted in order to obtain further information. Non-concurrence in quality assessment was reported.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Data types

We assessed outcomes using continuous (for example changes on a behaviour scale), categorical (for example, one of three categories on a behaviour scale, such as ’little change’, ’moderate change’ or ’much change’) or dichotomous (for example, either ’no important changes or ’important change’ in a person’s behaviour) measures. Currently RevMan does not support categorical data so we were unable to analyse this.

2. Dichotomous data

We carried out an intention to treat analysis. Everyone allocated to the intervention were counted, whether they completed the follow up or not. It was assumed that those who dropped out had no change in their outcome. This rule is conservative concerning response to treatment, because it assumes that those discontinuing the studies would not have responded. It is not conservative concerning adverse effects, but we felt that assuming that all those leaving early would have developed side effects would overestimate risk. Where possible, efforts were made to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This can be done by identifying cut off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into ’clinically improved’ or ’not clinically improved’. It was generally assumed that if there had been a 50% reduction in a scale-derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS, Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a, Leucht 2005b). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut-off presented by the original authors.

We calculated the relative risk (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) based on the random effects model, as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. It has been shown that RR is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This misinterpretation then leads to an overestimate of the impression of the effect. When the overall results were significant we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) and the number-needed-to-harm (NNH) as the inverse of the risk difference.

3. Continuous data

3.1 Normal distribution of the data

The meta-analytic formulas applied by RevMan Analyses (the statistical programme included in RevMan) require a normal distribution of data. The software is robust towards some skew, but to which degree of skewness meta-analytic calculations can still be reliably carried out is unclear. On the other hand, excluding all studies on the basis of estimates of the normal distribution of the data also leads to a bias, because a considerable amount of data may be lost leading to a selection bias. Therefore, we included all studies in the primary analysis. In a sensitivity analysis we excluded potentially skewed data applying the following rules:

When a scale started from the finite number zero the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, was more than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, Altman 1996).

If a scale started from a positive value (such as PANSS which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S-Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score.

In large studies (as a cut-off we used 200 participants) skewed data pose less of a problem. In these cases we entered the data in a synthesis.

The rules explained in a) and b) do not apply to change data.

The reasons is that when continuous data are presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values, it is difficult to tell whether data are non-normally distributed (skewed) or not. This is also the case for change data (endpoint minus baseline). In the absence of individual patient data it is impossible to know if data are skewed, though this is likely. After consulting the ALL-STAT electronic statistics mailing list, we presented change data in RevMan Analyses in order to summarise available information. In doing this, it was assumed either that data were not skewed or that the analysis could cope with the unknown degree of skew. Without individual patient data it is impossible to test this assumption. Change data were therefore included and a sensitivity analysis was not applied.

For continuous outcomes we estimated a weighted mean difference (WMD) between groups. WMDs were again based on the random effects model, as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. We combined both endpoint data and change data in the analysis, because there is no principal statistical reason why endpoint and change data should measure different effects (Higgins 2008). When standard errors instead of standard deviations (SD) were presented, we converted the former to standard deviations. If both were missing we estimated SDs from p-values or used the average SD of the other studies (Furukawa 2006).

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ ’cluster randomisation’ (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intraclass correlation in clustered studies, leading to a ’unit of analysis’ error (Divine 1992) whereby p values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997, Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intraclass correlation coefficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non-cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a ’design effect’. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) [Design effect=1+(m-1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account intraclass correlation coefficients and relevant data documented in the report, we synthesised these with other studies using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross-over trials

A major concern of cross-over trials is the carry-over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash-out phase. For the same reason cross-over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in schizophrenia, we will only use data of the first phase of cross-over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment groups, if relevant, the additional treatment groups were presented in additional relevant comparisons. Data were not double counted. Where the additional treatment groups were not relevant, these data were not reproduced.

Dealing with missing data

At some degree of loss of follow-up data must lose credibility (Xia 2007). Although high rates of premature discontinuation are a major problem in this field, we felt that it is unclear which degree of attrition leads to a high degree of bias. We, therefore, did not exclude trials on the basis of the percentage of participants completing them. However we addressed the attrition problem in all parts of the review, including the abstract. For this purpose we calculated, presented and commented on frequency statistics (overall rates of leaving the studies early in all studies and comparators pooled).

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all the included studies within any comparison to judge for clinical heterogeneity.

2. Statistical

2.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

2.2 Employing the I2 statistic

Visual inspection was supplemented using, primarily, the I2statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance alone. Where the I2 estimate was greater than or equal to 50% we interpreted this as indicating the presence of considerable levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in section 10.1 of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2008). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating small study effects but are of limited power to detect such effects when there are few studies. We entered data from all identified and selected trials into a funnel graph (trial effect versus trial size) in an attempt to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias. We did not undertake a formal test for funnel plot asymmetry.

Data synthesis

Where possible for both dichotomous and continuous data we used the random-effects model for data synthesis as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed or random-effects models. The random-effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This does seem true to us, however, random-effects does put added weight onto the smaller of the studies - those trials that are most vulnerable to bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If data are clearly heterogeneous we checked that data are correctly extracted and entered and that we had made no unit of analysis errors. If inconsistency was high and clear reasons explaining the heterogeneity were found, we presented the data separately. If not, we commented on the heterogeneity of the data.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analyses for examining the change in robustness of the sensitivity to including studies with potentially skewed data. A recent report showed that some of the comparisons of atypical antipsychotic drugs may have been biased by using inappropriate comparator doses (Heres 2006). We, therefore, also analysed whether the exclusion of studies with inappropriate comparator doses changed the results of the primary outcome and the general mental state.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

For substantive description of studies please see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

The overall search strategy yielded 3620 reports of which 104 were closely inspected.

Included studies

Twenty-one studies with 4101 participants met the inclusion criteria. Six studies were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies producing quetiapine, three were sponsored by the manufacturer of the comparator antipsychotic, and eight had a neutral sponsor. For the remaining four studies the sponsor was unclear.

1. Length of trials

Fifteen studies were short term with a duration of 2-12 weeks. Three studies were medium term and two trials fell into the long term category.

2. Setting

Seven trials were conducted in an in- or outpatient setting, nine studies were conducted exclusively in an inpatient setting and one study was conducted exclusively in an outpatient setting. Four studies did not report the setting.

3. Participants

Seventeen studies included participants with diagnoses according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fourth revision (DSM-IV). Riedel 2005 additionally used the International Classification of Diseases Version 10 (ICD-10). Li 2002, Li 2005 and Liu 2004 diagnosed participants according to the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders Version 3 (CCMD-3). Li 2003b used CCMD-2. Two studies included only acutely ill people (Riedel 2007, Svestka 2003b) and one included only people with a first episode of schizophrenia (McEvoy 2007). Two studies included people with chronic schizophrenia or people with more than one schizophrenic episode (Lieberman 2005, Stroup 2006). Only one study focused on treatment resistant participants (Conley 2005).

4. Study size

Lieberman 2005 was the largest study with 1453 participants, while Ozguven 2004 was the smallest, randomising only 22 people. Five studies had less than 50 participants but two randomised more than 400 people.

5. Interventions

5.1 Quetiapine: all included studies used flexible dosing

Overall, quetiapine was given in a dose range from 50 mg/day to 800 mg/day. Only Conley 2005 limited the upper dose range to 500 mg/day and Ozguven 2004 had a mean dose which was higher than the upper dose range of 800mg/day (827 mg/day).

5.2 Comparators: the comparator drugs were clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone and ziprasidone, again given in flexible doses

Some studies included treatment arms with fluphenazine, perphenazine and perospirone, as well, but as these are not second generation antipsychotic drugs we did not report the results.

6. Outcomes

6.1 Leaving the study early

The number of participants leaving the studies early were reported for the categories ‘any reason’, ‘adverse events’ and ‘lack of efficacy’.

6.2 No clinically significant response

We pre-specified at least 50% PANSS/BPRS reduction from baseline as a clinical relevant cut-off to define, but only Svestka 2003b reported this outcome. Instead, Liu 2004 indicated at least 50% SANS reduction from baseline, Potkin 2006 and Zhong 2006a at least 30 % PANSS total score reduction from baseline, Ozguven 2004 at least 20% SANS total score reduction from baseline, Conley 2005 a Clinical Global Impression (Guy 1976) of mild or better combined with at least 20% BPRS total reduction from baseline and McEvoy 2007 all PANSS items mild or better plus a Clinical Global Impression of mild or better.

6.3 Outcome scales

Details of scales that provided usable data are shown below. Reasons for exclusion of data from other instruments are given under ’Outcomes’ in the ’Included studies’ section.

6.3.1 Global state scales

6.3.1.1 Clinical Global Impression Scale - CGI (Guy 1976)

This is used to assess both severity of illness and clinical improvement, by comparing the conditions of the person standardised against other people with the same diagnosis. A seven point scoring system is usually used with low scores showing decreased severity and/or overall improvement.

6.3.2 Mental state scales

6.3.2.1 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale - PANSS (Kay 1986)

This schizophrenia scale has 30 items, each of which can be defined on a seven-point scoring system varying from 1 (absent) to 7 (extreme). It can be divided into three sub-scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS-P) and negative symptoms (PANSS-N). A low score indicates lesser severity.

6.3.2.2 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale - BPRS (Overall 1962)

This is used to assess the severity of abnormal mental state. The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18 item scale is commonly used. Each item is defined on a seven point scale varying from ’not present’ to ’extremely severe’, scoring from 0-6 or 1-7. Scores can range from 0-126 with high scores indicating more severe symptoms.

6.3.2.3 Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms - SANS (Andreasen 1989)

This six point scale gives a global rating of the following negative symptoms: alogia, affective blunting, avolition-apathy, anhedonia-associality and attention impairment. Higher scores indicate more symptoms.

6.3.2.4 Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms - SAPS (Andreasen 1984)

This four point scale gives a global rating of the following positive symptoms: hallucination, delusion, bizarre attitudes and positive formal thought disorder.

6.3.3 Global Assessment of Functioning - GAF (DSM IV 1994)

A rating scale for a patients’ overall capacity of psychosocial functioning, scoring from 1-100. Higher scores indicating a higher level of functioning.

6.3.4. Quality of Life Scale - QLS (Carpenter 1984)

This semi-structured interview is administered and rated by trained clinicians. It contains 21 items rated on a seven point scale based on the interviewers’ judgement of patient functioning. A total QLS and four sub-scale scores are calculated, with higher scores indicating less impairment.

6.3.5 Adverse effects scales

6.3.5.1 Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale - AIMS (Guy 1976)

This has been used to assess tardive dyskinesia, a long-term, drug-induced movement disorder and short-term movement disorders such as tremor.

6.3.5.2 Barnes Akathisia Scale - BAS (Barnes 1989)

The scale comprises items rating the observable, restless movements that characterise akathisia, a subjective awareness of restlessness and any distress associated with the condition. These items are rated from 0 - normal to 3 - severe. In addition, there is an item for rating global severity (from 0 - absent to 5 - severe). A low score indicates low levels of akathisia.

6.3.5.3 Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale - ESRS (Chouinard 1980)

This is a questionnaire relating to parkinsonian symptoms (nine items), a physician’s examination for parkinsonism and dyskinetic movements (eight items), and a clinical global impression of tardive dyskinesia. High scores indicate severe levels of movement disorder.

6.3.5.4 Simpson Angus Scale - SAS (Simpson 1970)

This is a ten item scale, with a scoring system of 0-4 for each item, measures drug-induced parkinsonism, a short-term drug-induced movement disorder. A low score indicates low levels of Parkinsonism.

6.4 Other adverse effects

Other adverse effects were reported as continuous variables for QTc prolongation (ms), cholesterol level (mg/dl), glucose level (mg/dl), prolactin level (ng/ml) and weight (kg). Other adverse events were reported in a dichotomous manner in terms of the number of people with a given effect.

6.5 Service use

Service use was described as the number of patients re-hospitalised during the trial.

Excluded studies

Eighty three studies had to be excluded for the following reasons: eleven were not randomised, 64 were open label, three employed inappropriate intervention, four reported no usable data and one was a pooled analysis rather than a trial.

Awaiting assessment

No studies are waiting assessment.

Ongoing studies

Four randomised trials comparing quetiapine with other antipsychotic drugs seem to be ongoing (Eli Lilly 2004b, Gafoor 2005, Ratna 2003, Reynolds 2001). For further details see ’Characteristics of ongoing studies’.

Risk of bias in included studies

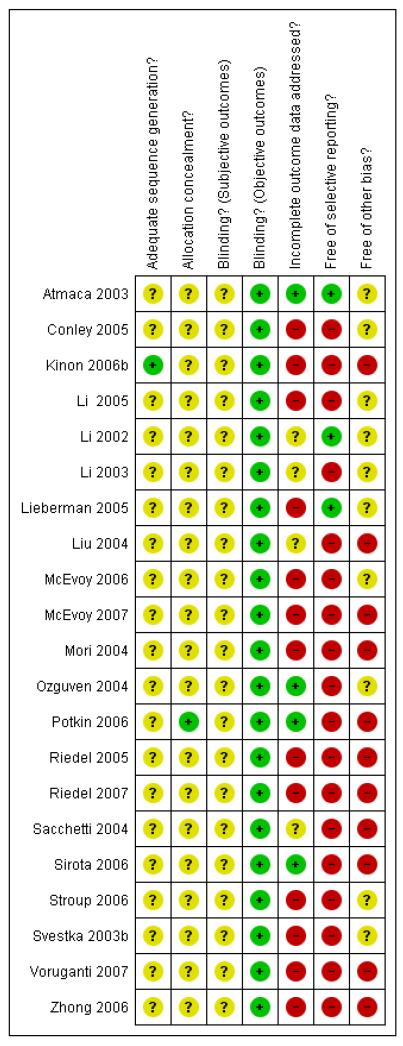

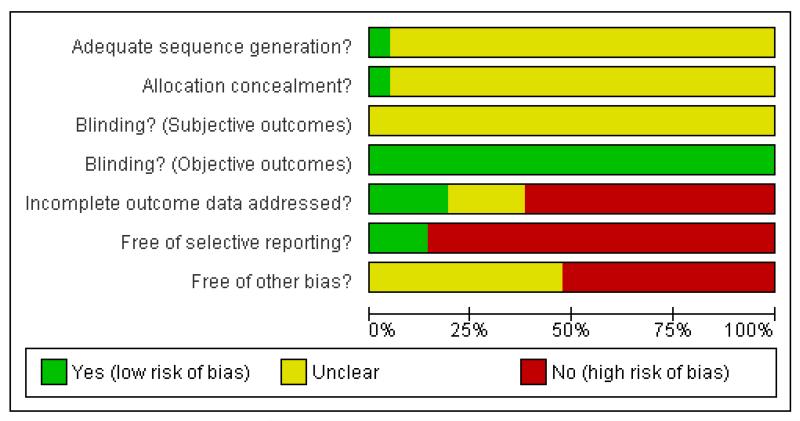

For details please refer to risk of bias tables (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Figure 1. Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Figure 2. Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

All of the included studies were described as randomised. Only two studies gave further information about the type of randomisation, Kinon 2006b described computer generated randomisation and Potkin 2006 described using an interactive voice response system for allocation concealment, for all other studies it was unclear whether the allocation strategies were appropriate.

Blinding

Seven of the included studies were ’single-blind’ (blind raters), all other included studies were ’double-blind’. Four studies used identical capsules for blinding (Lieberman 2005, McEvoy 2006, Potkin 2006, Riedel 2005). The other trials did not provide any information on the blinding procedure. No study examined whether blinding was effective. We found that the adverse effect profiles of some of the compounds are quite different and think that this may have made blinding difficult. We therefore conclude that the risk of bias for objective outcomes (e.g. death or laboratory values) was less than that for subjective outcomes, and for the latter there was a considerable risk as a result of poor blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Fifteen studies indicated the number of participants leaving the studies early for any reason. In these fifteen studies the reasons for premature study discontinuation were usually well described. A major problem, however, was the very high attrition which in nine studies was higher than 30% (57.6% overall) (Conley 2005, Kinon 2006b, Lieberman 2005, McEvoy 2006, McEvoy 2007, Riedel 2005, Riedel 2007, Stroup 2006, Zhong 2006). In most studies the last-observation-carried-forward method was used to account for attrition. This is an imperfect method. It assumes that a participant’s outcome would not have changed if he/she had remained in the study which is often wrong. It is, however, questionable whether other methods (e.g. imputation strategies or mixed effect models) could have coped better with such dramatically high rates of attrition. The high loss to follow up is a clear threat to the validity of findings.

Selective reporting

Only two studies were judged to be free of selective reporting (Atmaca 2003, Li 2002). For most of the other trials there was a high risk of bias, mainly for the reason of incomplete reporting of predefined outcomes (Conley 2005, Kinon 2006b, Li 2005, Li 2003, Liu 2004, McEvoy 2006, Mori 2004, Ozguven 2004, Riedel 2005, Riedel 2007, Sacchetti 2004, Sirota 2006, Stroup 2006, Svestka 2003b, Voruganti 2007). In other studies only adverse events that occurred in at least 5% or 10% of participants, or which were moderately severe, have been reported (McEvoy 2007, Potkin 2006, Zhong 2006). The former method is problematic, because rare but important adverse effects may have been missed. In Lieberman 2005 all data from one site were excluded before analysis because of concerns about their integrity.

Other potential sources of bias

No study was clearly free of other potential sources of bias. In six the risk of ‘other bias’ was, however, unclear. Nine studies were industry sponsored (Kinon 2006b, McEvoy 2007, Potkin 2006, Riedel 2005, Riedel 2007, Sacchetti 2004, Sirota 2006, Voruganti 2007, Zhong 2006). There is evidence that pharmaceutical companies sometimes highlight the benefits of their compounds and tend to suppress their disadvantages (Heres 2006). Other reasons for potential bias were heterogeneity of pre-study treatment (Atmaca 2003, Stroup 2006), lack of or only short wash-out phases (Li 2005, Lieberman 2005, McEvoy 2006, Mori 2004, Voruganti 2007), baseline imbalance in terms of number of previous hospitalisations (Conley 2005), no information on the allowed dose range (Atmaca 2003, Li 2003, Voruganti 2007), or a too fast titration of clozapine which may be associated with more adverse events (Liu 2004).

Effects of interventions

1. Comparison 1. QUETIAPINE versus CLOZAPINE - all data short term

Five studies met the inclusion criteria for the comparison of quetiapine with clozapine.

1.1 Global state

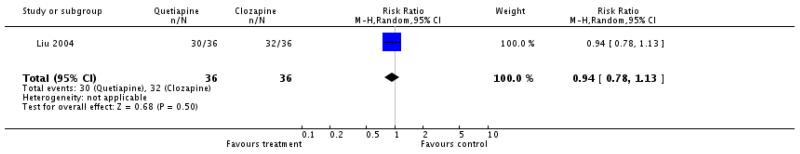

1.1.1 No clinically significant response - as defined by the original studies

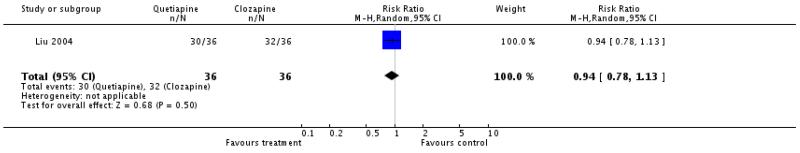

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=72, RR 0.94 CI 0.78 to 1.13).

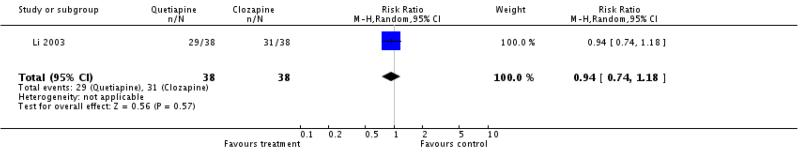

1.1.2 No clinically important change - as defined by the original studies

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=72, RR 0.94 CI 0.74 to 1.18).

1.2 Leaving the study early

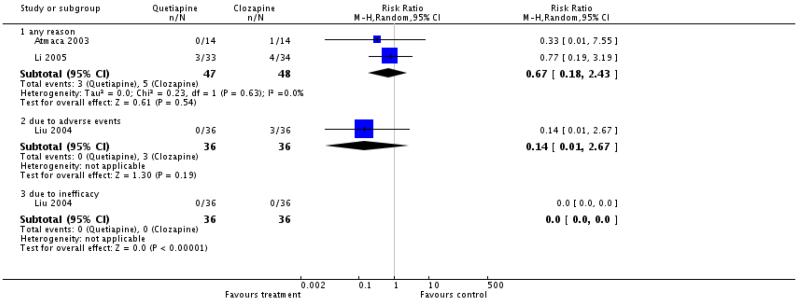

There was no significant difference in the number of participants leaving the studies early due to any reason (2 RCTs, n=95, RR 0.67 CI 0.18 to 2.43), due to adverse events (1 RCT, n=72, RR 0.14 CI 0.01 to 2.6) or due to inefficacy of treatment (1 RCT, n= 72, RR not estimable).

1.3 Mental state

1.3.1 General mental state: no clinically important change (less than 50% PANSS total score reduction from baseline)

There was no clear difference to be found (1 RCT, n=63, RR 1.07 CI 0.53 to 2.14).

1.3.2 General mental state: average score at endpoint - PANSS total

Four short term studies did not indicate a significant difference (4 RCTs, n=232, WMD −0.5 CI −2.85 to 1.86).

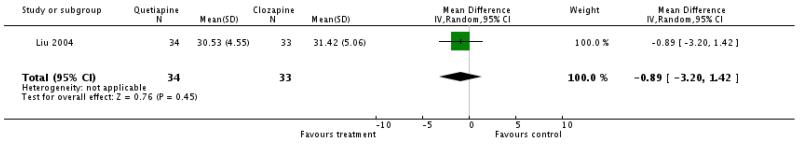

1.3.3 General mental state: average score at endpoint - BPRS total There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=67, WMD −0.89 CI −3.20 to 1.42).

1.3.4 Positive symptoms: average score at endpoint - PANSS positive subscore

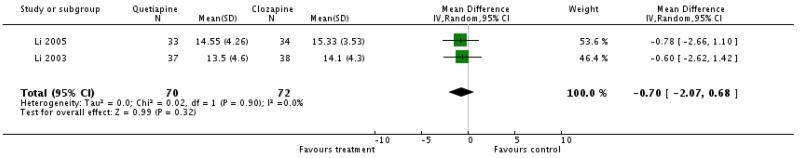

There was no significant difference (2 RCTs, n=142, WMD −0.7 CI −2.07 to 0.68).

1.3.5 Negative symptoms: average score at endpoint - PANSS negative subscore

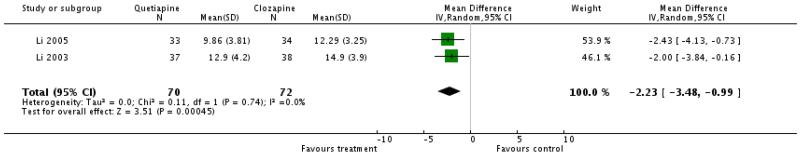

Two small Chinese studies showed a significant superiority of quetiapine (2 RCTs, n=142, WMD −2.23 CI −3.48 to −0.99).

1.3.6 Negative symptoms: no clinically important change (less than 50% SANS total score reduction from baseline)

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=72, RR 0.94 CI 0.78 to 1.13).

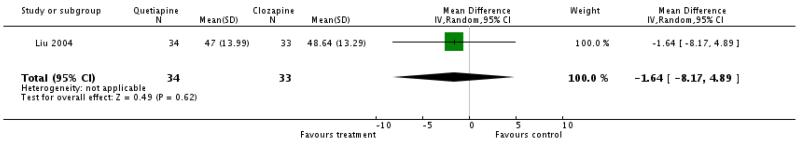

1.3.7 Negative symptoms: average score at endpoint - SANS total There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=67, WMD −1.64 CI −8.17 to 4.89).

1.4 Adverse effects

1.4.1 Numbers of participants with at least one adverse effect

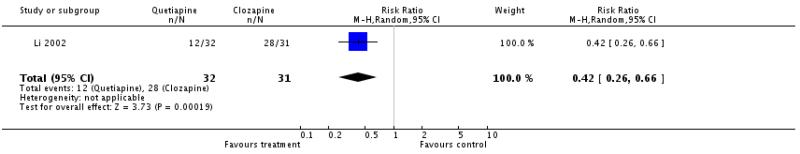

There was a significant difference, based on data from Li 2002, favouring the treatment group (1 RCT, n=63, RR 0.42 CI 0.26 to 0.66, NNH 2 CI 1 to 3).

1.4.2 Cardiac effects - ECG abnormalities

There was a significant difference favouring quetiapine (1 RCT, n=72, RR 0.13 CI 0.02 to 0.95, NNH 5 CI 3 to 20).

1.4.3 Central nervous system - sedation

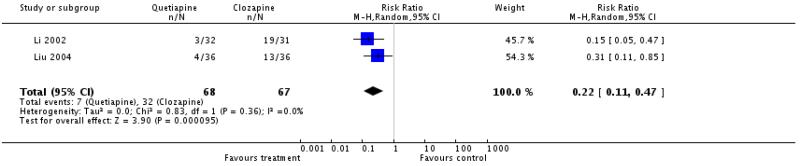

Fewer participants in the quetiapine group reported this outcome (2 RCTs, n=135, RR 0.22 CI 0.11 to 0.47, NNH 3 CI 2 to 8).

1.4.4 Extrapyramidal effects

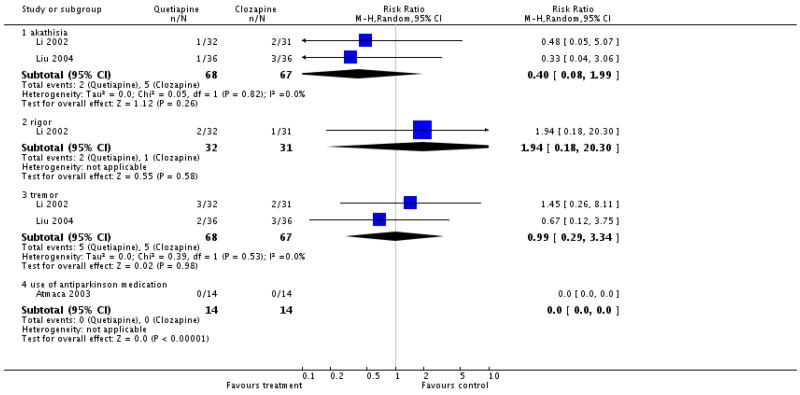

There was no significant difference in akathisia (2 RCTs, n=135, RR 0.4 CI 0.08 to 1.99), rigor (1 RCT, n=63, RR 1.94 CI 0.18 to 20.3), tremor (2 RCTs, n=135, RR 0.99 CI 0.29 to 3.34) or use of antiparkinsonian medication (1 RCT, n=28, RR not estimable).

1.4.5 Haematological: important decline in white blood cells

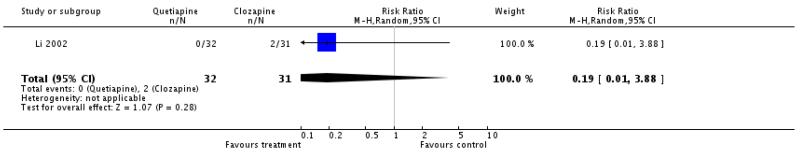

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=33, RR 0.19 CI 0.01 to 3.88).

1.4.6 Metabolic - weight gain (number of participants with significant weight gain)

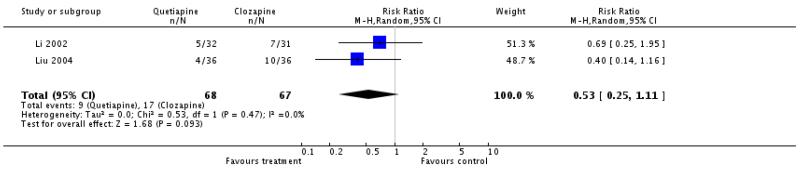

There was no significant difference (2 RCTs, n=135, RR 0.53 CI 0.25 to 1.11).

1.4.7 Metabolic - weight gain (change from baseline in kg)

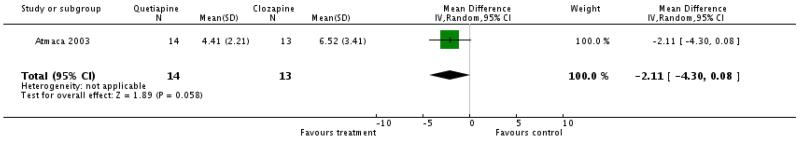

One small study reported a trend in favour of quetiapine (1 RCT, n=27, WMD −2.11 CI −4.3 to 0.08).

1.5 Publication bias

We did not perform a funnel plot analysis because there were so few studies.

1.6 Investigation for heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis

The exclusion of Li 2002, Li 2003b, Li 2005 from the analysis of the PANSS total score due to possibly skewed data did not change the results to a marked extent.

2. Comparison 2. QUETIAPINE versus OLANZAPINE

Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria for this comparison.

2.1 Global state

2.1.1 No clinically significant response - as defined by the original studies

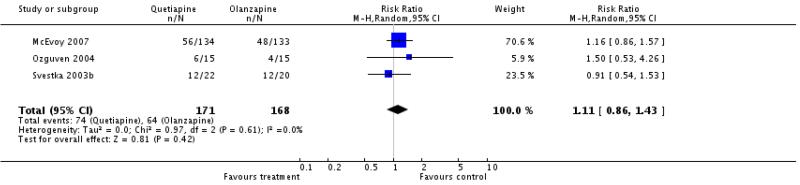

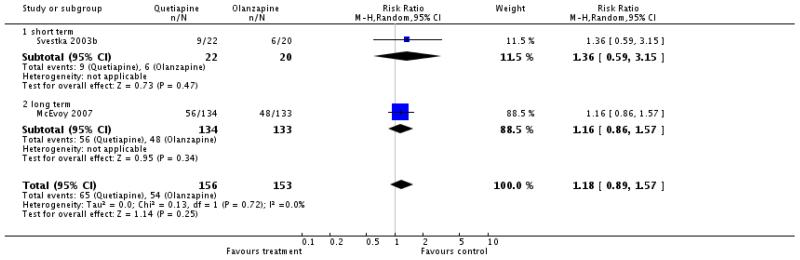

There was no significant difference (3 RCTs, n=339, RR 1.11 CI 0.86 to 1.43).

2.1.2 No clinically important change - as defined by the original studies

There was no significant difference (2 RCTs, n=309, RR 1.18 CI 0.89 to 1.57).

2.2 Leaving the study early

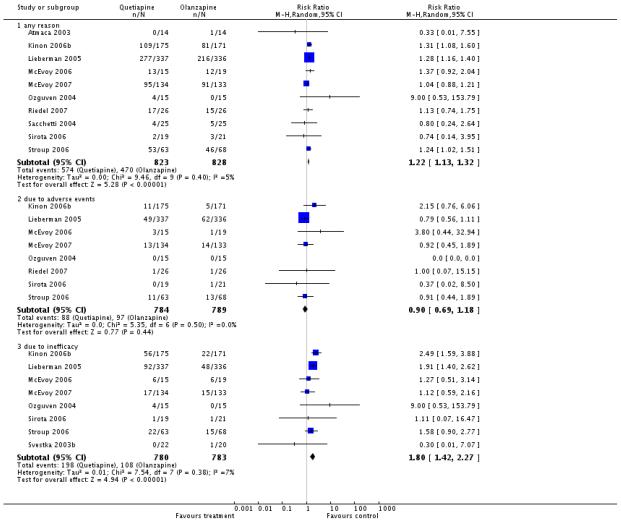

Fewer participants in the olanzapine group (57%) compared with the quetiapine group (70%) left the studies early because of ‘any reason’ (10 RCTs, n=1651, RR 1.22 CI 1.13 to 1.32, NNH 10 CI 6 to 33) or ‘inefficacy’ (14% versus 25%, 8 RCTs, n=1563, RR 1.8 CI 1.42 to 2.27, NNH 11 CI 6 to 50), but not due to adverse events (12% versus 11%, 8 RCTs, n=1573, RR 0.90 CI 0.69 to 1.18).

2.3 Mental state

2.3.1 General mental state: no clinically important change - short term (less than 50% PANSS total score reduction)

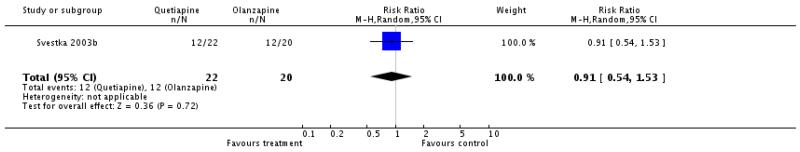

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=42, RR 0.91 CI 0.54 to 1.53).

2.3.2 General mental state: average score at endpoint - PANSS total

There was a significant difference favouring olanzapine (10 RCTs, n=1449, WMD 3.66 CI 1.93 to 5.39) in the short term (4 RCTs, n=142, WMD 2.17 CI -1.51 to 5.85), medium term (3 RCTs, n= 483, WMD 5.57 CI 1.97 to 9.17) and long term (3 RCT, n=825, WMD 3.40 CI 0.91 to 5.88)

2.3.3 Positive symptoms: no clinically important change - short term (less than 20% SAPS total score reduction)

There was no difference identified with confidence (1 RCT, n=30, RR 15.0 CI 0.93 to 241.2).

2.3.4 Positive symptoms: average score at endpoint - PANSS positive subscore

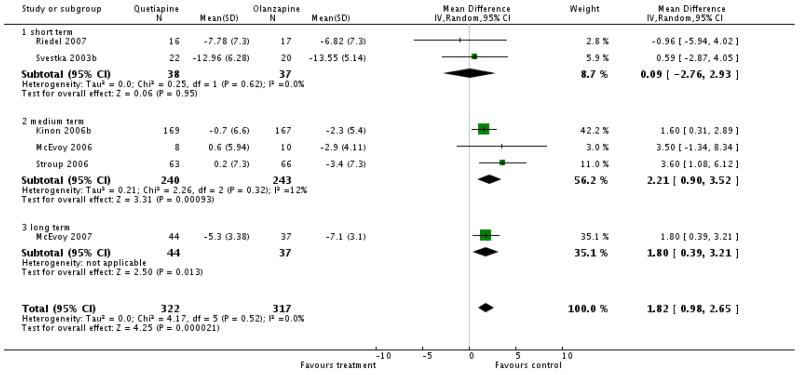

There was a significant difference in favour of olanzapine (7 RCTs, n=679, WMD 1.8 CI 1.02 to 2.59), short term (3 RCTs, n=115, WMD 1.05 CI −0.75 to 2.85), medium term (3 RCTs, n=483, WMD 2.21 CI 0.90 to 3.52), long term (1 RCT, n=81, WMD 1.80 CI 0.39 to 3.21)

2.3.5 Positive symptoms: average score at endpoint - SAPS total score - short term (percentage change from baseline)

There was a significant difference favouring olanzapine (1 RCT, n=30, WMD 40.84 CI 23.97 to 57.71).

2.3.6 Negative symptoms: no clinically important change - short term (less than 20% SANS total score reduction from baseline)

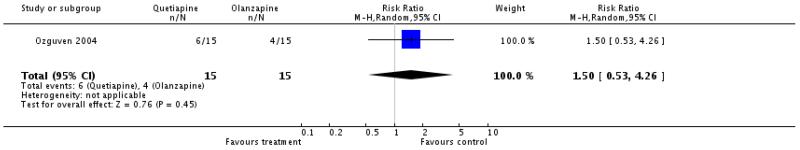

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=30, RR 1.5 CI 0.53 to 4.26).

2.3.7 Negative symptoms: average score at endpoint - PANSS negative subscore

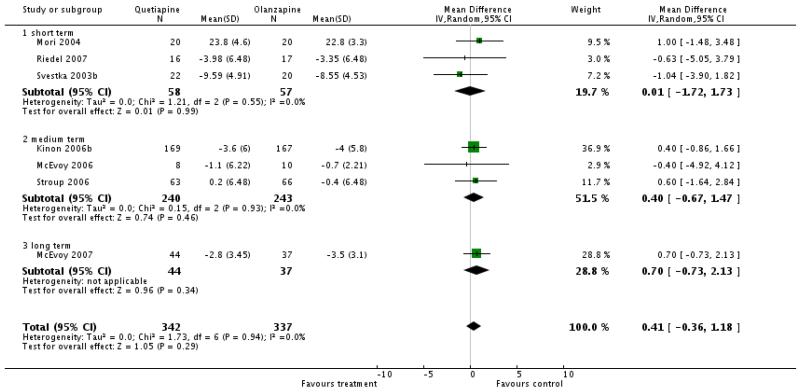

There was no significant difference (7 RCTs, n=679, WMD 0.41 CI −0.36 to 1.18), short term (3 RCTs, n=115, WMD 0.01 CI −1.72 to 1.73), medium term (3 RCTs, n=483, WMD 0.40 CI −0.67 to 1.47), long term (1 RCT, n=81, WMD 0.70 CI −0.73 to 2.13)

2.3.8 Negative symptoms: average score at endpoint - SANS total score

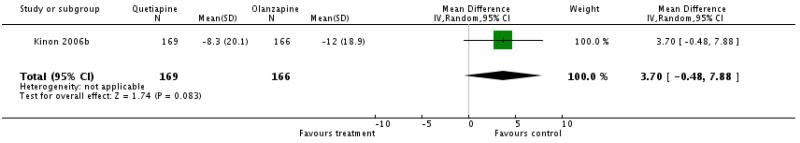

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=335, WMD 3.7 CI −0.48 to 7.88).

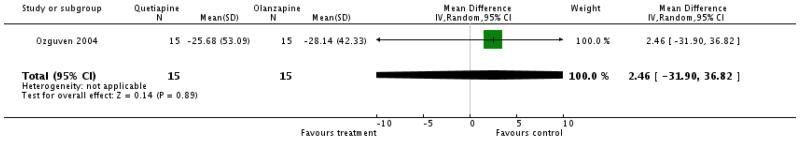

2.3.9 Negative symptoms: average score at endpoint - SANS total score (percent change from baseline)

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=30, WMD 2.46 CI −31.9 to 36.82).

2.4 General functioning: average endpoint total score -medium term GAF

There was a significant difference in favour of olanzapine (1 RCT, n=278, WMD 3.8 CI 0.77 to 6.83).

2.5 Quality of life: average endpoint total score -medium term QLS

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=286, WMD 1.8 CI −2.42 to 6.02).

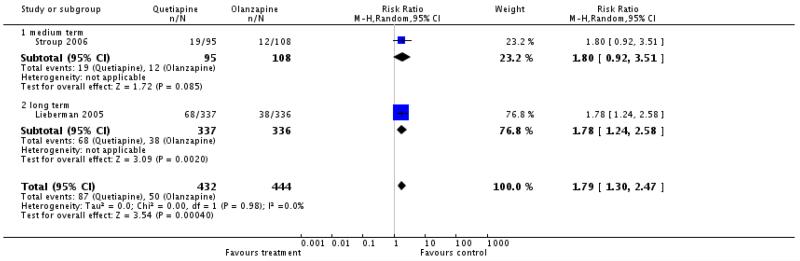

2.6 Service use: number of participants re-hospitalised

There was a significant difference favouring olanzapine (2 RCTs, n=876, RR 1.79 CI 1.30 to 2.47, NNH 11 CI 7 to 25).

2.7 Adverse effects

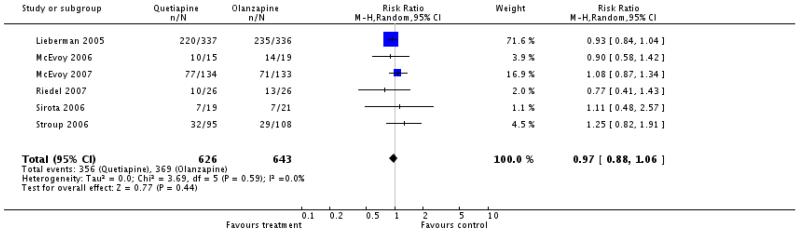

2.7.1 Numbers of participants with at least one adverse effect

There was no significant difference (6 RCTs, n=1269, RR 0.97 CI 0.88 to 1.06).

2.7.2 Death

There was no significant difference (4 RCTs, n=1410, RR 0.74 CI 0.13 to 4.23).

2.7.3 Cardiac effects

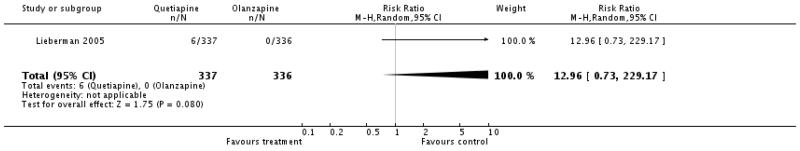

2.7.3.1 Number of participants with QTc prolongation

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=673, RR 12.96 CI 0.73 to 229.17).

2.7.3.2 Mean change of QTc interval from baseline in ms

There was a significant difference favouring olanzapine (3 RCTs, n=643, WMD 4.81 CI 0.34 to 9.28).

2.7.4 Central nervous system

2.7.4.1 Sedation

There was no significant difference (7 RCTs, n=1615, RR 0.97 CI 0.78 to 1.2).

2.7.4.2 Seizures

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=40, RR 3.3 CI 0.14 to 76.46).

2.7.5 Extrapyramidal effects

2.7.5.1 Extrapyramidal effects

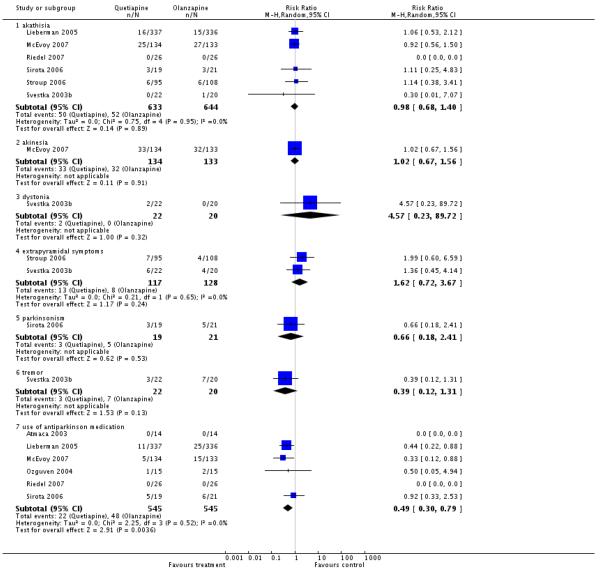

Fewer participants in the quetiapine group used antiparkinson medication at least once (6 RCTs, n=1090, RR 0.49 CI 0.3 to 0.79, NNH 25 CI 14 to 100). Apart from this, no significant differences in EPS were found for akathisia (6 RCTs, n=1277, RR 0.98 CI 0.68 to 1.4), akinesia (1 RCT, n=267, RR 1.02 CI 0.67 to 1.56), dystonia (1 RCT, n=42, RR 4.57 CI 0.23 to 89.72), any extrapyramidal symptom (2 RCTs, n=245, RR 1.62 CI 0.72 to 3.67), parkinsonism (1 RCT, n=40, RR 0.66 CI 0.18 to 2.41) and tremor (1 RCT, n=44, RR 0.39 CI 0.12 to 1.31).

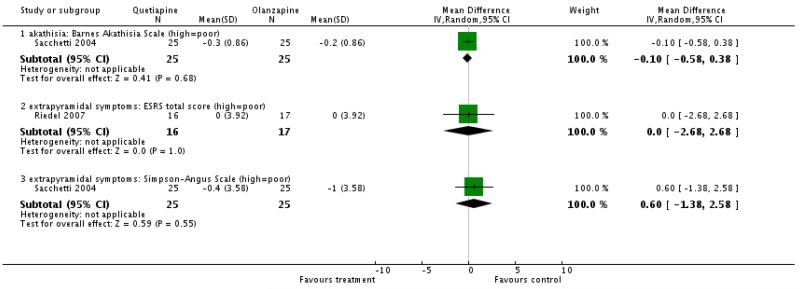

2.7.5.2 Scale measured

Extrapyramidal adverse effects were evaluated with the Barnes Akathisia Scale, the Extrapyramidal Side Effects Rating Scale and the Simpson-Angus Scale. None of these indicated a significant difference between groups.

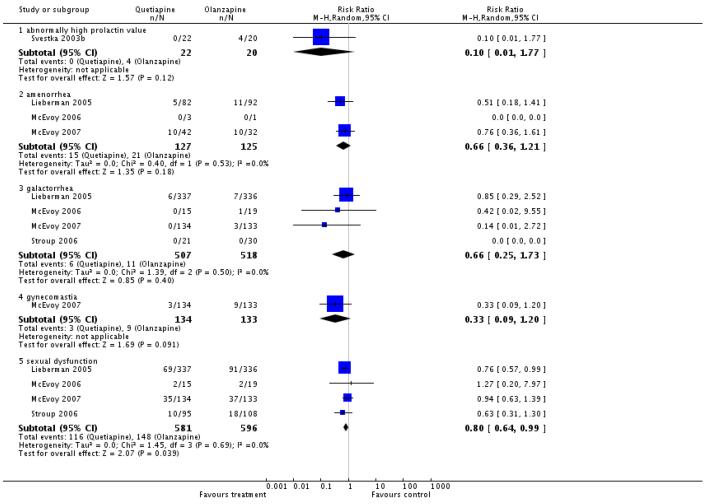

2.7.6 Prolactin associated side effects

Fewer participants in the quetiapine group suffered from sexual dysfunction (4 RCTs, n=1177, RR 0.8 CI 0.64 to 0.99, NNH 20 CI 10 to 100).

There was no significant difference in abnormally high prolactin (1 RCT, n=42, RR 0.10 CI 0.01 to 1.77), amenorrhoea (3 RCTs, n=252, RR 0.66 CI 0.36 to 1.21), galactorrhoea (4 RCTs, n=1025, RR 0.66 CI 0.25 to 1.73) and gynaecomastia (1 RCT, n=267, RR 0.33 CI 0.09 to 1.20).

2.7.7 Prolactin - change from baseline in ng/ml

Quetiapine was associated with less prolactin increase than olanzapine (5 RCTs, n=1021, RR −5.89 CI −11.62 to −0.16), but the data were heterogeneous. Nevertheless, the single-studies reported a consistent effect in favour of quetiapine (Svestka 2003b: n=35, WMD −40.07 CI −64.10 to −16.04, Lieberman 2005: n=673, WMD −3.20 CI − 6.81 to 0.41, McEvoy 2006: n=29, WMD −9.10 CI −19.88 to 1.68, Stroup 2006: n=203, WMD −3.20 CI −11.17 to 4.77, and McEvoy 2007: n=81, WMD −2.80 CI −10.03 to 4.43). Heterogeneity seems more due to differences in degree of prolactin increase rather than direction of effect.

2.7.8 Metabolic

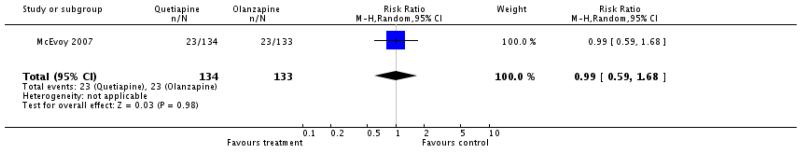

2.7.8.1 Cholesterol - number of participants with abnormally high cholesterol increase

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=267, RR 0.99 CI 0.59 to 1.68).

2.7.8.2 Cholesterol - mean change from baseline in mg/dl

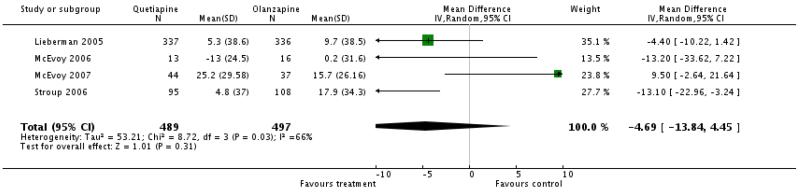

Overall data on cholesterol change from baseline did not show a statistically significant difference between groups (4 RCTs, n=986, WMD −4.69 CI −13.84 to 4.45). There was significant heterogeneity due to one outlier (McEvoy 2007) which was a first-episode study and showed a trend in favour of olanzapine. Excluding this study revealed a significant difference in favour of quetiapine (3 RCTs, n=643, WMD −7.84 CI −14.12 to −1.57).

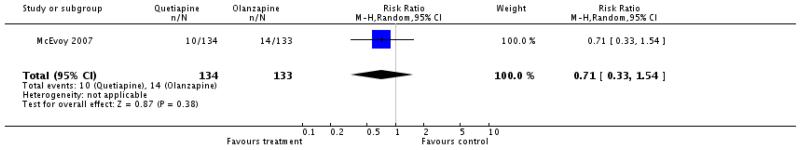

2.7.8.3 Glucose - number of participants with abnormally high fasting glucose

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=267, RR 0.71 CI 0.33 to 1.54).

2.7.8.4 Glucose - change from baseline in mg/dl

The mean increase of glucose from baseline was lower in the quetiapine group than in the olanzapine group (4 RCTs, n=986, WMD −9.32 CI −17.82 to −0.82). The data remained heterogeneous even after an outlier study (McEvoy 2007) was excluded, but the superiority of quetiapine remained.

2.7.8.5 Weight gain

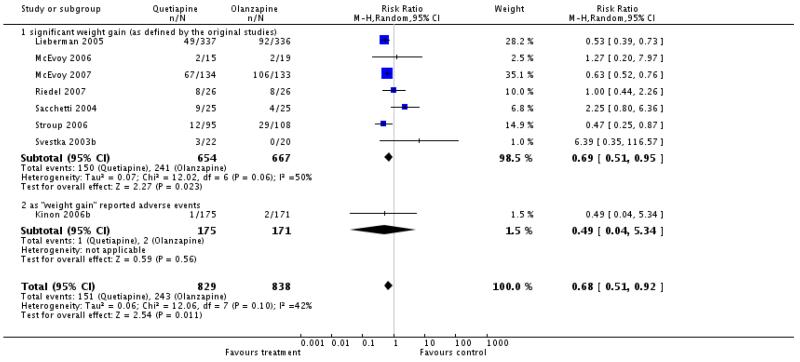

Fewer participants in the quetiapine group had a significant weight gain (8 RCTs, n=1667, RR 0.68 CI 0.51 to 0.92, NNH not estimable).

2.7.8.6 Weight gain - change from baseline in kg

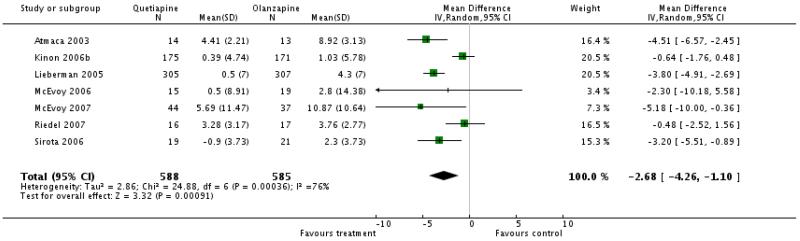

Overall participants in the quetiapine group gained less weight than in the olanzapine group (7 RCT, n=1173, WMD −2.68 CI −4.26 to −1.10). Again, there was significant heterogeneity, but the results of the single studies consistently favoured quetiapine (Atmaca 2003: n=27, WMD −4.51 CI −6.57 to −2.45, Lieberman 2005: n=612, WMD −3.8 CI −4.91 to −2.69, Kinon 2006b: n=346, WMD −0.64 CI −1.76 to 0.48), McEvoy 2006: n=34, WMD −2.3 CI −10.18 to 5.58, Sirota 2006: n=40, WMD −3.2 CI −5.51 to −0.89, McEvoy 2007: n=81, WMD −5.18 CI −10.00 to −0.36, Riedel 2007: n=33, WMD −0.48 CI −2.52 to 1.56).

2.8 Publication bias

Funnel plots did not suggest a possible publication bias.

2.9 Investigation for heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis

When Mori 2004 was excluded from the evaluation of the PANSS positive score due to possibly skewed data olanzapine remained more effective.

3. Comparison 3. QUETIAPINE versus RISPERIDONE

Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria for the comparison of quetiapine with risperidone.

3.1 Global state

3.1.1 No clinically significant response - as defined by the original studies

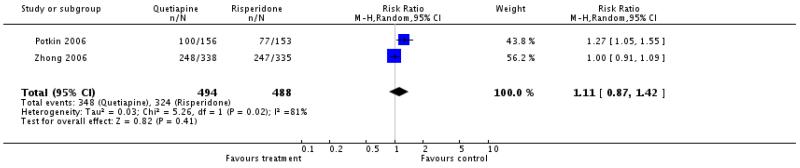

Overall there was no significant difference. As the results were heterogeneous we present the single studies separately. Potkin 2006 reported a significant difference in favour of risperidone (n=177, RR 1.27 CI 1.05 to 1.55), while Conley 2005 (n=25, RR not estimable), Zhong 2006a (n=495, RR 1.0 CI 0.91 to 1.09) and McEvoy 2007 (n=103, RR 1.18 CI 0.87 to 1.6) found no significant difference between groups. The first three studies reported short term and only McEvoy 2007 reported long term data.

3.1.2 No clinically important change (as defined by the original studies)

There was a small superiority of risperidone which did not reach statistical significance (4 RCTs, n=1374, RR 1.16 CI 0.99 to 1.35).

3.2 Leaving the study early

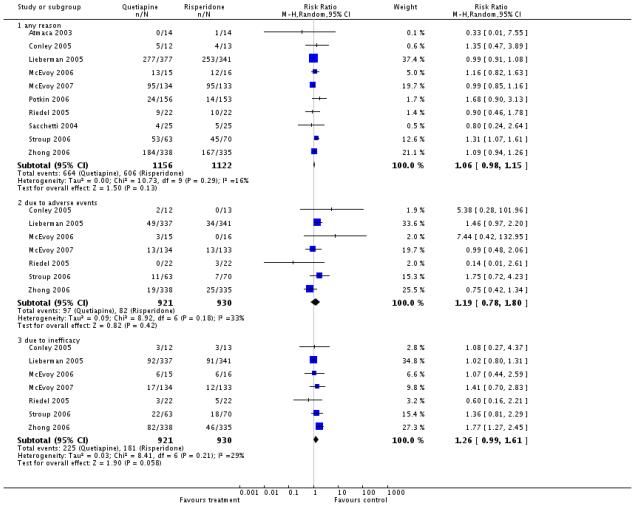

There was no significant difference in the number of participants leaving the studies early due to any reason (quetiapine 57%, risperidone 54%, 10 RCTs, n=2278, RR 1.06 CI 0.98 to 1.15) or due to adverse events (11% versus 9%, 7 RCTs, n=1851, RR 1.19 CI 0.78 to 1.8). Leaving early due to inefficacy showed an almost significant superiority of risperidone (24% versus 19%, 7 RCTs, n=1851, RR 1.26 CI 0.99 to 1.61).

3.3 Mental state

3.3.1 General mental state: no clinically important change - short term (less than 30% PANSS total score reduction from baseline)

There was no significant difference (2 RCTs, n=984, RR 1.11 CI 0.87 to 1.42), but the results were heterogeneous. We therefore present the single studies separately: Potkin 2006 (n=177, RR 1.27 CI 1.05 to 1.55) and Zhong 2006a (n=495, RR 1.0 CI 0.91 to 1.09).

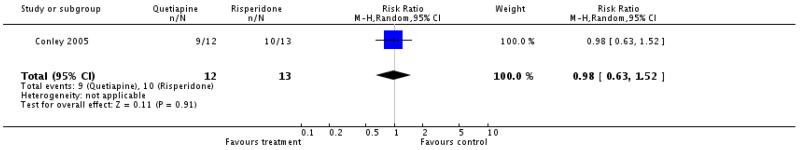

3.3.2 General mental state: no clinically important change - short term (less than 20% BPRS total score reduction) There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=25, RR 0.98 CI 0.63 to 1.52).

3.3.3 General mental state: average score at endpoint - PANSS total

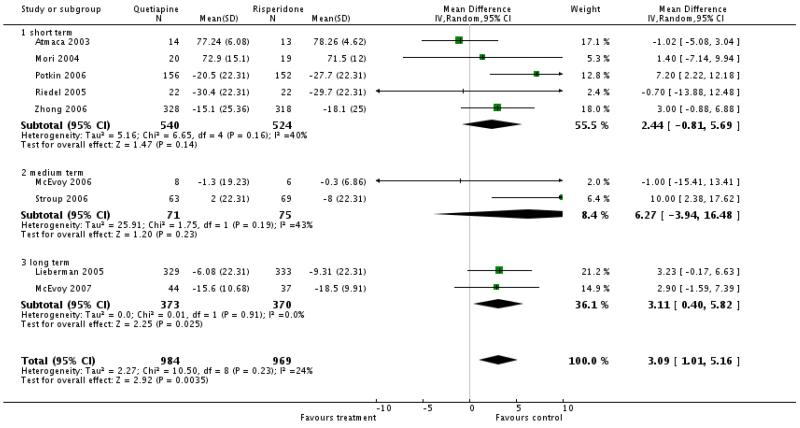

There was a significant difference in favour of risperidone: overall (9 RCTs, n=1953, WMD 3.09 CI 1.01 to 5.16), short term (5 RCTs, n=1064, WMD 2.44 CI −0.81 to 5.69), medium term (2 RCTs, n=146, WMD 6.27 CI −3.94 to 16.48), long term (2 RCTs, n=743, WMD 3.11 CI 0.40 to 5.82)

3.3.4 General mental state: average score at endpoint - short term - BPRS total

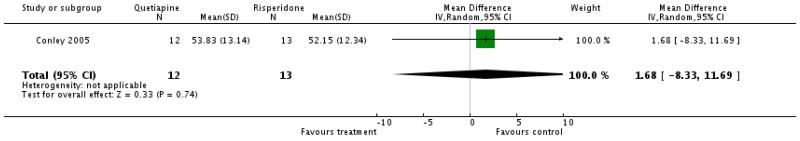

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=25, WMD 1.68 CI −8.33 to 11.69).

3.3.5 Positive symptoms - no clinically important change - short term (less than 40% PANSS positive score reduction from baseline)

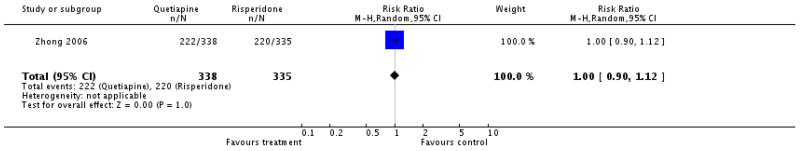

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=673, RR 1.00 CI 0.9 to 1.12).

3.3.6 Positive symptoms: average score at endpoint - PANSS positive subscore

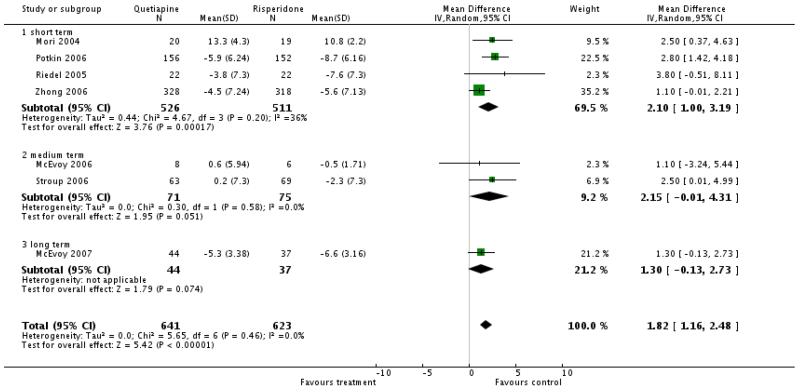

There was a significant difference favouring risperidone overall (7 RCTs, n=1264, WMD 1.82 CI 1.16 to 2.48), short term (4 RCTs, n=1037, WMD 2.10 CI 1.00 to 3.19), medium term (2 RCTs, n=146, WMD 2.15 CI −0.01 to 4.31), long term (1 RCT, n=81, WMD 1.30 CI −0.13 to 2.73)

3.3.7 Positive symptoms: average score at endpoint - short term-BPRS positive subscore

There was a significant difference favouring risperidone (1 RCT, n=25, WMD 1.1 CI 0.18 to 2.02).

3.3.8 Negative symptoms - no clinically important change - short term (less than 40% PANSS negative score reduction from baseline)

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=673, RR 0.98 CI 0.93 to 1.04).

3.3.9 Negative symptoms: average score at endpoint PANSS negative subscore

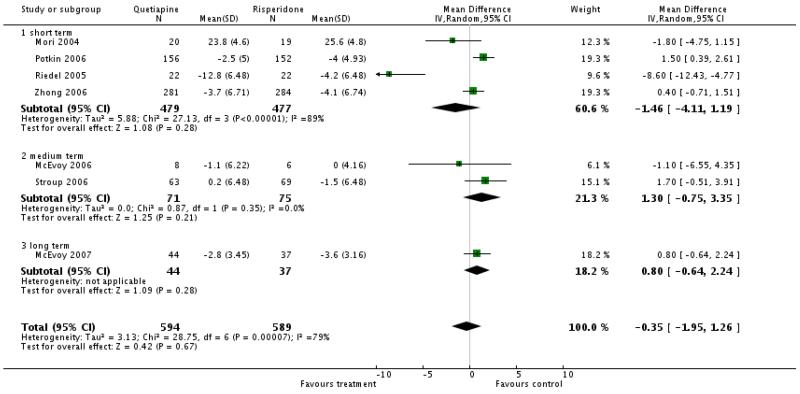

There was no significant difference (short term studies, 4 RCTs, n=956, WMD −1.46 CI −4.11 to 1.19; medium term studies, 2 RCTs, n=146, WMD 1.3 CI −0.75 to 3.35; long term stud, 1 RCT, n=81, WMD 0.8 CI −0.64 to 2.24). The short-term results were highly heterogeneous. Excluding a small outlier study (Riedel 2005) in a sensitivity analysis there was a significant superiority of risperidone (6 RCTs, n=1139, WMD 0.79 CI 0.04 to 1.54).

3.3.10 Negative symptoms: average score at endpoint - short term - BPRS negative subscore

There was a significant difference favouring risperidone (1 RCT, n=25, WMD 0.57 CI 0.17 to 0.97).

3.4 Quality of life: average endpoint score - short term - QLS total score

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=25, WMD −0.5 CI −13.87 to 12.87).

3.5 Service use: number of participants re-hospitalised

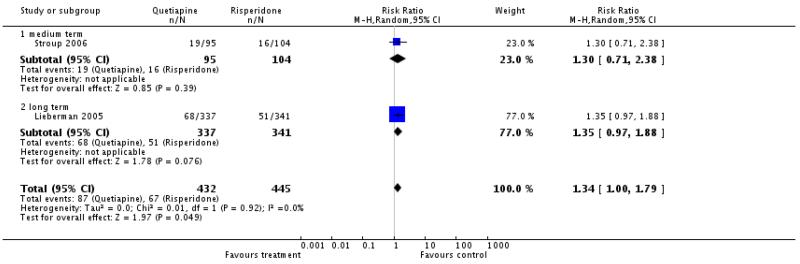

The difference almost reached statistical significance with a slight benefit for the risperidone group (2 RCTs, n=877, RR 1.34 CI 1.0 to 1.79).

3.6 Adverse effects

3.6.1 General: at least one adverse effect

There was no significant difference (8 RCTs, n=2226, RR 1.04 CI 0.93 to 1.17).

3.6.2 Death

There was no significant difference (7 RCTs, n=3066, RR 0.73 CI 0.17 to 3.09).

3.6.3 Cardiac effects

3.6.3.1. Number of participants with QTc prolongation

There was no significant difference (2 RCTs, n=1351, RR 0.87 CI 0.29 to 2.55).

3.6.3.2 Mean change of QTc interval from baseline in ms

Overall there was no significant difference (3 RCT, n= 940, WMD 2.21 CI −5.05 to 9.48). The data were heterogeneous. In the individual studies Lieberman 2005 found a significant difference in favour of risperidone (n=432, WMD 5.7 CI 0.57 to 10.83), while Stroup 2006 (n=166, WMD 6.3 CI −3.41 to 16.01) and Zhong 2006a (n=342, WMD −3.6 CI −7.55 to 0.35) found no significant difference between groups.

3.6.4 Central nervous system - sedation

There was a significant difference favouring risperidone (8 RCTs, n=2226, RR 1.21 CI 1.06 to 1.38, NNH 20 CI 11 to 50).

3.6.5 Extrapyramidal effects

3.6.5.1 Extrapyramidal effects

Quetiapine produced fewer movement disorders than risperidone in terms of ’extrapyramidal symptoms’ (2 RCTs, n=872, RR 0.59 CI 0.43 to 0.81, NNH 14 CI 8 to 33), dystonia (1 RCT, n= 673, RR 0.06 CI 0.01 to 0.41, NNH 20 CI 13 to 33) and use of antiparkinson medication at least once (6 RCTs, n=1715, RR 0.5 CI 0.3 to 0.86, NNH 20 CI 10 to 100). However, there was no significant difference in akathisia (6 RCTs, n=2170, RR 0.62 CI 0.34 to 1.13), akinesia (1 RCT, n=267, RR 0.91 CI 0.61 to 1.37) or parkinsonism (1 RCT, n=44, RR 0.06 CI 0.0 to 0.96).

3.6.5.2 As measured by scales

Quetiapine produced fewer extrapyramidal side effects than risperidone according to the Simpson-Angus Scale (5 RCTs, n= 1077, WMD −0.59 CI −1.16 to −0.02). There was no significant difference in dyskinesia (AIMS, 2 RCTs, n=958, WMD −0.34 CI-0.75 to 0.08) and akathisia (BAS, 2 RCTs, n=700, WMD −0.73 CI −2.0 to 0.54).

3.6.6 Haematological: important decline in white blood cells

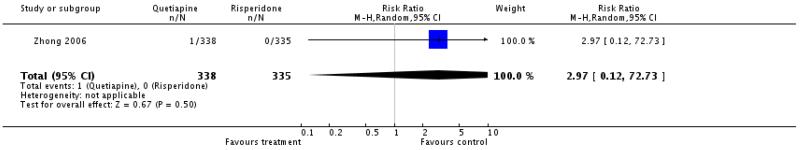

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=673, RR 2.97 CI 0.12 to 72.73).

3.6.7 Prolactin

3.6.7.1 Prolactin associated adverse effects

Quetiapine produced significantly fewer cases of amenorrhoea (4 RCTs, n=359, RR 0.47 CI 0.28 to 0.79, NNT not estimable), galactorrhoea (5 RCTs, n=478, RR 0.38 CI 0.17 to 0.84, NNT 25 CI 13 to 100) and gynaecomastia (1 RCT, n=78, RR 0.23 CI 0.07 to 0.75, NNT 4 CI 2 to 11), but not dysmenorrhoea (1 RCT, n=163, RR 0.45 CI 0.08 to 2.38). Data on sexual dysfunction showed an almost significant superiority of quetiapine (6 RCTs, n=2157, RR 0.70 CI 0.48 to 1.01).

3.6.7.2 Change from baseline in ng/ml

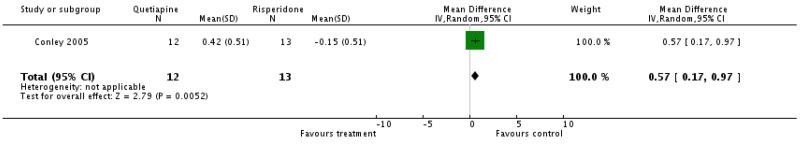

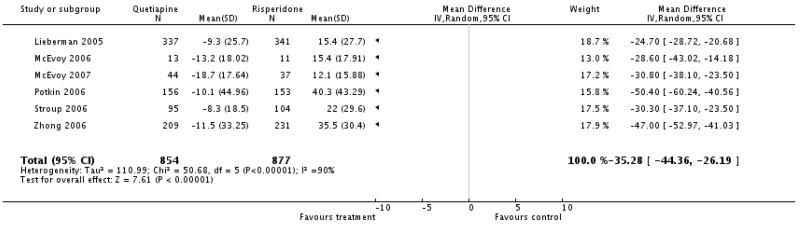

There was a significant and consistent difference favouring quetiapine although the amount of the difference varied leading to statistical heterogeneity (6 RCTs, n=1731, WMD −35.28 CI −44.36 to −26.19; the results of the single studies were: Lieberman 2005, n=678, WMD −24.70 CI −28.72 to −20.68; McEvoy 2006, n=24, WMD −28.6 CI −43.02 to −14.18; Potkin 2006 n=309, WMD −50.4 CI −60.24 to −40.56; Stroup 2006, n=199, WMD −30.3 CI −37.1 to −23.5; Zhong 2006a, n=440, WMD −47.0 CI −52.97 to −41.03), McEvoy 2007, n=81, WMD −30.8 CI −38.1 to −23.5).

3.6.8 Metabolic

3.6.8.1 Cholesterol - number of participants with a significant cholesterol increase

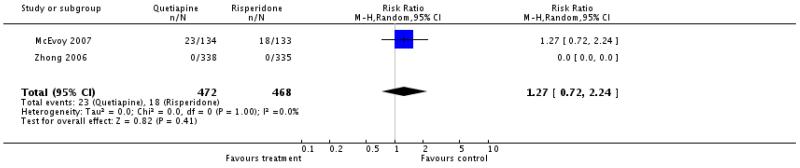

There was no significant difference (2 RCTs, n=940, RR 1.27 CI 0.72 to 2.24).

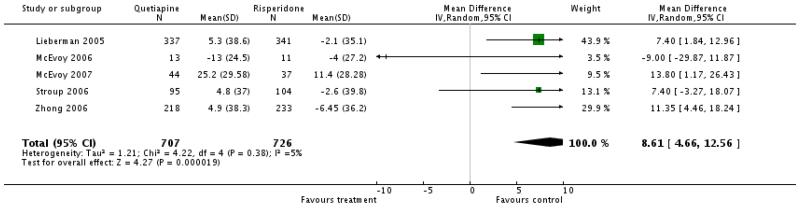

3.6.8.2 Cholesterol - mean change from baseline in mg/dl

There was a significant difference favouring risperidone (5 RCTs, n=1433, WMD 8.61 CI 4.66 to 12.56).

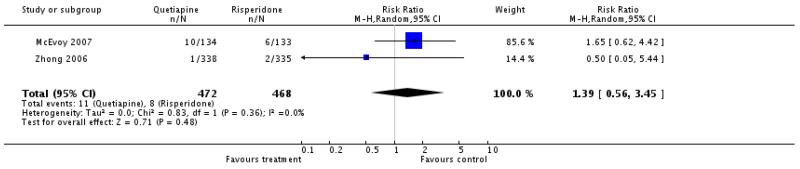

3.6.8.3 Glucose - number of participants with abnormally high fasting glucose

There was no significant difference (2 RCTs, n=940, RR 1.39 CI 0.56 to 3.45).

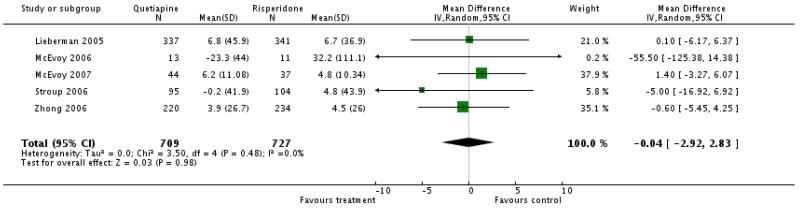

3.6.8.4 Glucose - mean change from baseline in mg/dl

There was no significant difference (5 RCTs, n=1436, WMD −0.04 CI −2.92 to 2.83).

3.6.8.5 Weight gain - number of participants with 7% or more gain of total body weight

There was no significant difference (7 RCTs, n=1942, RR 0.97 CI 0.82 to 1.14).

3.6.8.6 Weight gain - mean change from baseline in kg

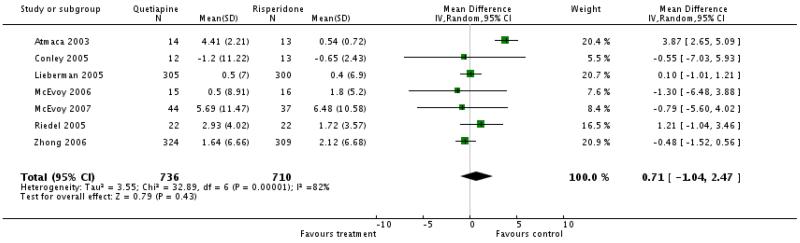

Overall there was no significant difference, but the data were highly heterogeneous presumably due to one small outlier study (Atmaca 2003) that showed a dramatic advantage of risperidone (7 RCTs, n=1446, WMD 0.71 CI −1.04 to 2.47). Nevertheless, excluding this study did not change the overall result.

3.7 Publication bias

A reasonable funnel plot analysis was only possible for the PANSS total score (>10 included studies). It did not suggest a possible publication bias.

3.8 Investigation for heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis

Excluding Mori 2004 from the evaluation of the PANSS positive subscore due to possibly skewed data did not reveal markedly different results. The data on akathisia (Barnes Akathisia Scale) indicated a considerable heterogeneity but clear reasons explaining this could not be found.

4. Comparison 4. QUETIAPINE versus ZIPRASIDONE

Two studies met the inclusion criteria for the comparison quetiapine versus ziprasidone.

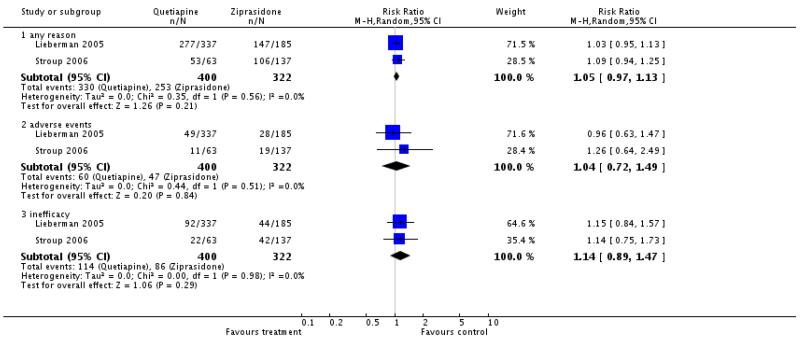

4.1 Leaving the study early

There was no significant difference in the number of participants leaving the studies early due to any reason (2 RCTs, n=722, RR 1.05 CI 0.97 to 1.13), due to adverse events (2 RCTs, n=722, RR 1.04 CI 0.72 to 1.49) or due to inefficacy of treatment (2 RCTs, n=722, RR 1.14 CI 0.89 to 1.47).

4.2 Mental state

4.2.1 General mental State: average score at endpoint - PANSS total

There was no significant difference, but the data of two studies were heterogeneous and are therefore presented separately. Neither Stroup 2006 (medium term data) n=198, WMD 3.7 CI −2.97 to 10.37 nor Lieberman 2005 (long term data) n=512, WMD −2.78 CI −6.81 to 1.25 found a a significant difference between groups.

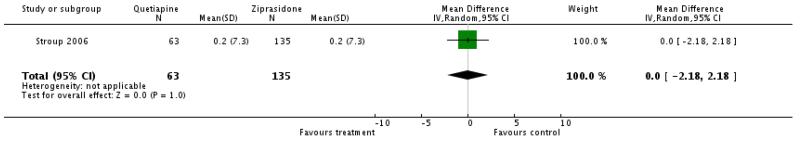

4.2.2 Positive Symptoms: average score at endpoint - medium term - PANSS positive subscore

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=198, WMD 0.0 CI −2.18 to 2.18).

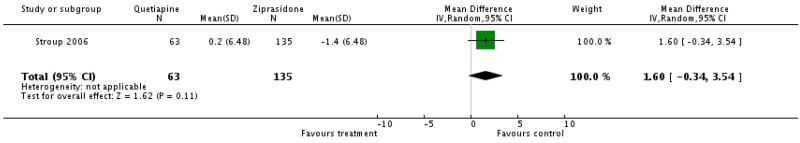

4.2.3 Negative Symptoms: average score at endpoint - medium term - PANSS negative subscore

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=198, WMD 1.6 CI −0.34 to 3.54).

4.3 Service use: number of participants re-hospitalised

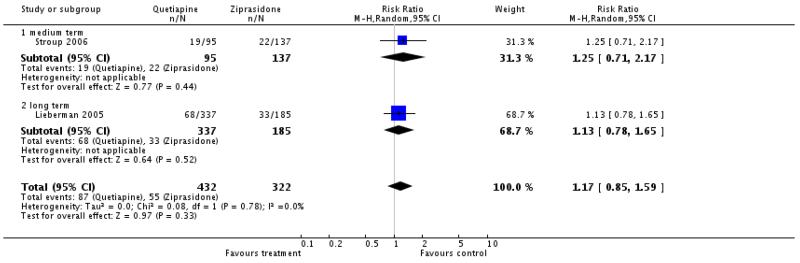

There was no significant difference neither in the overall analysis (2 RCTs, n=754, RR 1.17 CI 0.85 to 1.59) nor in the analysis of medium term data (1 RCT, n=232, RR 1.25 CI 0.71 to 2.17), or long term data (1 RCT, n=522, RR 1.13 CI 0.78 to 1.65)

4.4 Adverse effects

4.4.1 General - at least one adverse effect

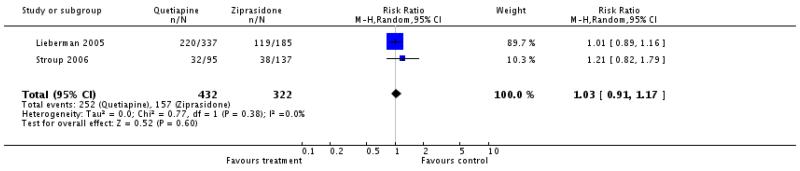

There was no significant difference (2 RCTs, n=754, RR 1.03 CI 0.91 to 1.17).

4.4.2 Death

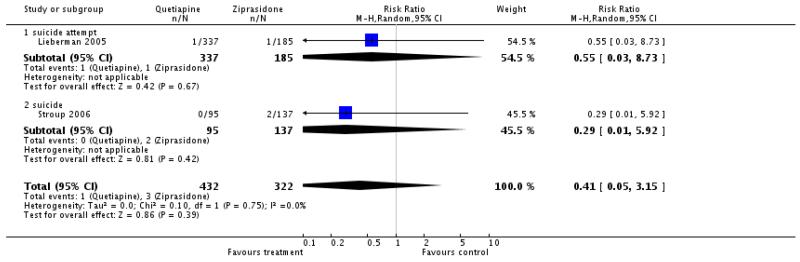

There was no significant difference (2 RCTs, n=754, RR 0.41 CI 0.05 to 3.15).

4.4.3 Cardiac effects

4.4.3.1 Number of participants with QTc prolongation

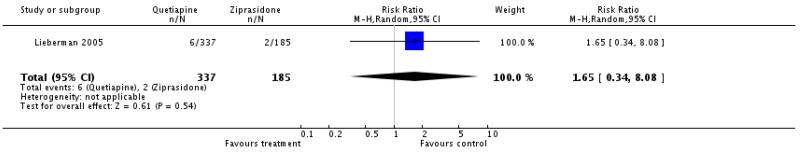

There was no significant difference (1 RCT, n=522, RR 1.65 CI 0.34 to 8.08).

4.4.3.2 mean change of QTc interval ms

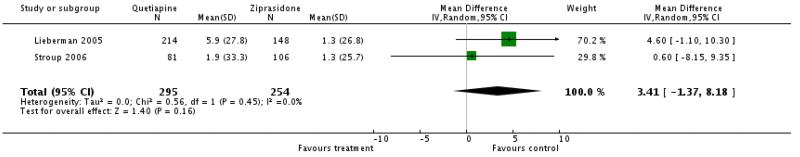

There was no significant difference (2 RCTs, n=549, WMD 3.41 CI −1.37 to 8.18).

4.4.4 Central nervous system -sedation

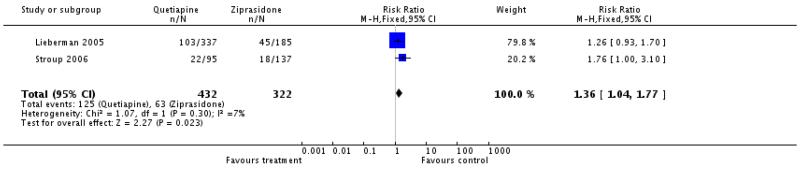

Significantly fewer participants in the ziprasidone group than in the quetiapine group felt sedated (2 RCTs, n=754, RR 1.36 CI 1.04 to 1.77, NNH 14 CI 7 to 100).

4.4.5 Extrapyramidal effects

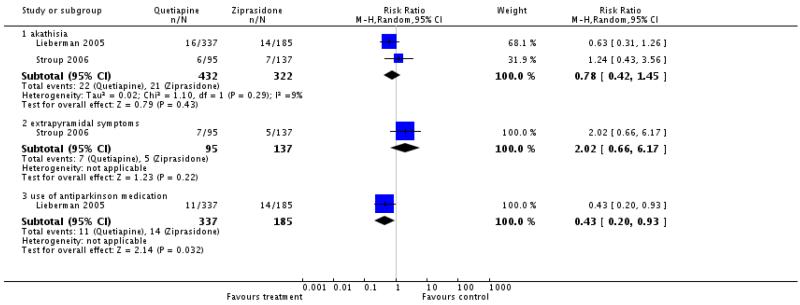

Significantly fewer people in the quetiapine group used antiparkinson medication at least once (1 RCT, n=522, RR 0.43 CI 0.2 to 0.93), but there were no clear differences in akathisia (2 RCTs, n=754, RR 0.78 CI 0.42 to 1.45) or ’any extrapyramidal symptoms’ (1 RCT, n=232, RR 2.02 CI 0.66 to 6.17).

4.4.6 Prolactin

4.4.6.1 Prolactin-associated adverse effects

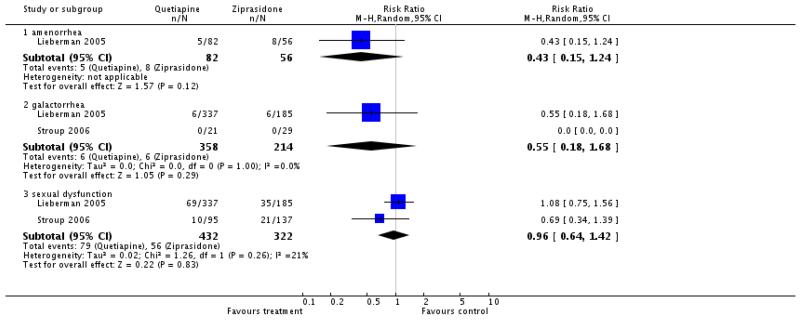

There was no significant difference in amenorrhoea (1 RCT, n=138, RR 0.43 CI 0.15 to 1.24), galactorrhoea (2 RCTs, n=202, RR 0.68 CI 0.23 to 2.01) or sexual dysfunction (2 RCTs, n=754, RR 0.96 CI 0.64 to 1.42).

4.4.6.2 Mean change from baseline in ng/ml

There was a significant difference in favour of quetiapine (2 RCTs, n=754, WMD −4.77 CI −8.16 to −1.37).

4.4.7 Metabolic

4.4.7.1 Cholesterol - mean change from baseline in mg/dl

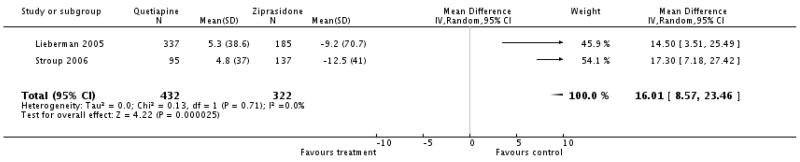

Ziprasidone was associated with significantly less cholesterol increase than quetiapine (2 RCTs, n=754, WMD 16.01 CI 8.57 to 23.46).

4.4.7.2 Glucose - mean change from baseline in mg/dl

There was no significant difference (2 RCTs, n=754, WMD 3.1 CI −3.99 to 10.19).

4.4.7.3 Weight gain - number of participants with 7% or more gain of total body weight

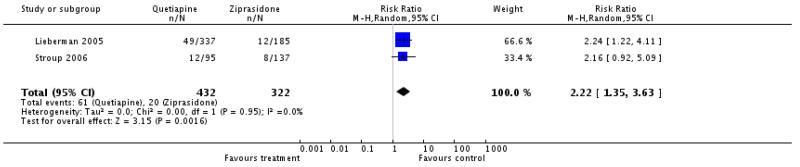

Significantly more participants in the quetiapine group than in the ziprasidone group gained weight (2 RCTs, n=754, RR 2.22 CI 1.35 to 3.63, NNH 13 CI 8 to 33).

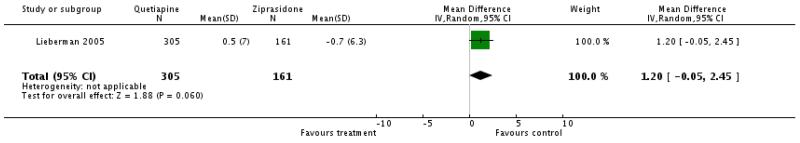

4.4.7.4 Weight gain - change from baseline in kg

There was a superiority of ziprasidone which almost reached statistical significance (1 RCT, n= 466, WMD 1.2 CI −0.05 to 2.45).

4.5 Publication bias

Due to small number of included studies we did not perform a funnel plot analysis.

4.6 Investigation for heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis

The reasons for the preplanned sensitivity analysis did not apply and were therefore not performed.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

1. General

This analysis of the effects of quetiapine compared with other second generation antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of schizophrenia currently includes 21 studies reporting data on only four of eight possible comparisons. High discontinuation rates (overall 57.6 %) limit the value of findings. In addition, 15 of the 21 included studies randomised less than 100 people. The duration of the trials was usually short and we identified only two long term studies. Short term trials are not ideal to judge efficacy and tolerability of treatments for a chronic disease. Nine of the 21 studies were sponsored by a pharmaceutical industry with a clear pecuniary interest in the result. This is likely to be a further problem.

2. Comparison 1. QUETIAPINE versus CLOZAPINE

Five studies with a total of 334 participants fell into this comparison.

2.1 Leaving the studies early

The overall rate of participants leaving studies early was remarkably low (8.4%) and showed no clear difference between groups. Nevertheless, this finding was based on only two small (n=135), short term trials limiting any interpretation.

2.2 Efficacy outcomes (global state, overall and specific mental state)

There was no significant difference in global state, general mental state or positive symptoms. Quetiapine reduced negative symptoms more than clozapine, but this result must be interpreted with great caution as it was based on two small trials from China (Li 2003b, Li 2005).

2.3 Adverse effects

We found limited data on ‘at least one adverse effect’, cardiac effects, extrapyramidal symptoms, sedation, weight gain and white blood cell count. Results on ‘at least one adverse effect’, cardiac effects and sedation indicated an advantage for quetiapine. As these findings were based on only one or two studies they can not be considered to be robust.

3. Comparison 2. QUETIAPINE versus OLANZAPINE

Most of the studies included in the review contributed data to this comparison (N=13, n=1820).

3.1 Leaving the studies early

Less people in the olanzapine group compared with the quetiapine group left studies early because of ‘any reason’ or due to ‘inefficacy of treatment’. This finding suggests that olanzapine is a more acceptable treatment than quetiapine, at least in the confines of clinical trials. Nevertheless, the overall rate of premature study discontinuations was high (63.2%), limiting the validity of all other results.

3.2 Efficacy outcomes (global state, overall and specific mental state)

Quetiapine seems to be slightly less effective than olanzapine for the general mental state and for positive symptoms. There was no significant difference in the reduction of negative symptoms. The interpretation of the latter finding is, however, limited by the fact that most studies included participants with predominant positive symptoms. Such studies are not ideal for evaluating the effects of antipsychotic drugs on negative symptoms.

3.3 General functioning and quality of life

Very limited data on these important outcomes are available. Olanzapine may improve general functioning (GAF total score) more than quetiapine, but this result was based on a single study and needs to be replicated. There are no data indicating a difference in measures of quality of life.

3.4 Service use: number of participants re-hospitalised

The number of participants re-hospitalised was significantly higher in the quetiapine group. Again, this may reflect a certain efficacy advantage of olanzapine, but as this result was based on only two studies more data are needed.

3.5 Adverse effects

Adverse effects were reported as at least one adverse effect, cardiac effects, QTc abnormalities, increase of serum cholesterol, serum glucose, serum prolactin and associated side effects, death, extrapyramidal symptoms, the occurrence of sedation, seizures and weight gain. Among these adverse effects a benefit for quetiapine was found for the use of antiparkinson medication (a proxy measure for extrapyramidal adverse effects), weight gain, glucose elevation, prolactin increase, and some prolactin-associated adverse effects. On the other hand there was a certain superiority of olanzapine in terms of QTc prolongation. Overall, it seems that quetiapine may be more tolerable than olanzapine, but this is weighed against slightly less efficacy.

4. Comparison 3. QUETIAPINE versus RISPERIDONE

Eleven studies with 3770 participants met the inclusion criteria for this comparison.

4.1 Leaving the studies early

There was no clear difference in the number of participants leaving the studies early suggesting a similar overall acceptability of quetiapine and risperidone. Nevertheless, the overall discontinuation rate was high (56.7%) limiting the interpretation of all other results.

4.2 Efficacy outcomes (global state, overall and specific mental state)

The only differences in efficacy were found for the general mental state and positive symptoms. Quetiapine was less effective than risperidone in these aspects of psychopathology. Nevertheless, the differences were small (e.g. only three points on the PANSS total score).

4.3 Adverse effects

Adverse effects were available for at least one adverse effect, cardiac effects, cholesterol increase, changes in serum glucose, increase of prolactin level and associated side effects, death, extrapyramidal adverse effects, sedation, weight gain and white blood cell count. Among these, quetiapine was better than risperidone in various measures of extrapyramidal adverse effects and prolactin associated effects. On the other hand quetiapine was associated with more sedation and cholesterol increase than risperidone. These differences in the adverse effect profile and the slightly lower efficacy of quetiapine may be weighed in drug choice.

5. Comparison 4. QUETIAPINE versus ZIPRASIDONE

Only two studies with 722 participants provided data on this comparison.

5.1 Leaving the studies early

The overall number of participants leaving the studies early very high (80.7%), clearly limiting the interpretation of any findings beyond the outcome of ‘leaving the study early’. There was no significant difference between groups, but the acceptability of both compounds seems to be poor.

5.2 Efficacy outcomes (global state, overall and specific mental state)

Various efficacy outcomes revealed no difference between quetiapine and ziprasidone. There is currently no randomised data suggesting that either drug should be preferred due to better efficacy.

5.3 Adverse effects

Adverse effects were reported as at least one adverse effect, cardiac effects, death, extrapyramidal side effects, changes in cholesterol, glucose and prolactin, the occurrence of sedation and weight gain. Among those reported there was an advantage of quetiapine in use of antiparkinson medication and prolactin levels, while weight gain and sedation favoured ziprasidone. Treatment decisions should take these differences in the adverse effect profiles into account.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We did not identify a single study for almost half of the possible comparisons of quetiapine with other second generation antipsychotic drugs. Evidence, therefore, is incomplete. Only two studies were long term, limiting applicability of the evidence as, after all, schizophrenia is often a chronic, often life-long, disorder. Furthermore, most of the included studies were efficacy studies, therefore external validity is limited and further effectiveness [pragmatic/real world] studies are needed.

Quality of the evidence

All studies were randomised and at least single-blind, but details were rarely presented. Therefore it is unclear in almost all studies whether randomisation and blinding were really appropriately done. Furthermore the high numbers of participants leaving the studies early (overall 57.6%) and the small number of long term studies (Lieberman 2005, McEvoy 2007, Voruganti 2007) call the validity of the findings into question. Selective reporting was evident in all but two studies and nine studies were industry sponsored. All these factors limit the quality of the evidence.

Potential biases in the review process

We are not aware of obvious flaws in our review process.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A previous Cochrane review compared the effects of quetiapine with placebo, first generation antipsychotic drugs and second generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia (Srisurapanont 2004). A single study fell in the last category and compared quetiapine with risperidone. This update and reformatting of the review has identified many new studies, and data are far more comprehensive.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

1. For people with schizophrenia

For people with schizophrenia it may be important to know that most people who start the drug within short trials choose to stop taking it within a few weeks. Quetiapine may also be slightly less effective than risperidone and olanzapine. Quetiapine may have low risk for extrapyramidal adverse effects and prolactin increase and may lead to less weight gain and associated problems than olanzapine, but more so than risperidone and ziprasidone.

2. For clinicians

Clinicians should know that, for only four out of eight possible comparisons of quetiapine with other second generation antipsychotic drugs, relevant studies were identified and that the evidence is limited because very high rates of participants leave the studies early. Our most robust finding is that if a person is started on quetiapine most will be off this drug within a few weeks. Certainly, more studies comparing quetiapine with other second generation antipsychotic drugs are needed.

3. For managers/policy makers

Little information on service use (such as time in hospital) or functioning is available, but the limited data suggest that people on quetiapine may need to be hospitalised more frequently than those receiving risperidone or olanzapine. This may be accompanied by higher overall costs in some settings. Furthermore, a single study suggested better general functioning of participants treated with olanzapine. We do not feel that these findings are sufficiently robust to guide managers.

Implications for research

1. General

We stress how important it is that future studies strictly adhere to the CONSORT statement (Moher 2001). Following these recommendations would clearly improve the conduct and reporting of clinical trials.

2. Specific